Abstract

In spite of wide availability of menstrual regulation services, women often resort to a variety of medicines for inducing abortion. The Bangladeshi Government is now supporting attempts to investigate the introduction of medical menstrual regulation in the public sector. This study examined the acceptability of medical menstrual regulation in public sector urban-based clinics, public sector rural-based clinics and urban-based clinics run by Marie Stopes, a non-governmental organization. Of the 2,976 women who attended for menstrual regulation services during the eight-month study period, 68% attended urban Maternal and Child Welfare Centres and the Marie Stopes clinics, while 32% went to the rural public facilities of the Union Health and Family Welfare Centre. Women were offered both medical and manual vacuum aspiration methods of menstrual regulation; 1,875 (63%) chose the medical method and 1,101 (37%) chose manual vacuum aspiration. Around 7.1% of women at Maternal and Child Welfare centres and 11.9% at the Marie Stopes clinics knew about medical menstrual regulation before taking the service, compared to a much higher proportion (43%) at the rural facilities. Overall 61.4% of women who used medical menstrual regulation found the method satisfactory, and 34.2% were very satisfied. Of the 3.9% of women who were not satisfied, most received services from rural facilities.

Résumé

Malgré la large disponibilité de services de régulation menstruelle, les femmes ont souvent recours à différents médicaments pour induire l’avortement. Le Gouvernement bangladeshi soutient maintenant les activités de recherche sur l’introduction de la régulation menstruelle médicamenteuse dans le secteur public. Cette étude a examiné l’acceptabilité de la régulation menstruelle médicamenteuse dans les dispensaires urbains du secteur public, les dispensaires ruraux du secteur public et les dispensaires urbains gérés par Marie Stopes, une organisation non gouvernementale. Des 2976 femmes ayant utilisé les services de régulation menstruelle pendant les huit mois de l’étude, 68% s’étaient rendues dans les dispensaires urbains des Maternal and Child Welfare Centres et Marie Stopes, alors que 32% étaient allées dans les dispensaires publics ruraux de l’Union Health and Family Welfare Centre. Les femmes avaient le choix entre des méthodes de régulation menstruelle médicamenteuses et par aspiration manuelle ; 1875 (63%) ont choisi la méthode médicamenteuse, alors que 1101 (37%) optaient pour l’aspiration manuelle. Près de 7,1% des femmes dans les centres de bien-être maternel et infantile et 11,9% dans les dispensaires Marie Stopes connaissaient la régulation menstruelle médicamenteuse avant de bénéficier du service, contre une proportion beaucoup plus élevée (43%) dans les centres ruraux. Dans l’ensemble, 61,4% des femmes qui ont utilisé la régulation menstruelle médicamenteuse ont jugé la méthode satisfaisante, et 34,2% en étaient très satisfaites. La plupart des 3,9% des femmes qui n’étaient pas satisfaites avaient été traitées dans des centres ruraux.

Resumen

A pesar de la amplia disponibilidad de servicios de regulación menstrual, las mujeres a menudo recurren a una variedad de medicamentos para inducir el aborto. El Gobierno de Bangladesh está respaldando intentos por investigar la introducción de la regulación menstrual con medicamentos en el sector público. Este estudio examinó la aceptabilidad de la regulación menstrual con medicamentos en clínicas urbanas del sector público, clínicas rurales del sector público y clínicas urbanas dirigidas por Marie Stopes, una organización no gubernamental. De las 2976 mujeres que asistieron para recibir servicios de regulación menstrual durante los ocho meses del estudio, el 68% asistió a un Maternal and Child Welfare Centre urbano o a una clínica de Marie Stopes, mientras que el 32% acudió a una unidad de salud pública rural del Union Health and Family Welfare Centre. A las mujeres se les ofrecieron tanto el método con medicamentos como la aspiración manual endouterina para la regulación menstrual; 1875 (63%) eligieron el método con medicamentos y 1101 (37%) eligieron la aspiración manual endouterina. Aproximadamente el 7.1% de las mujeres en Maternal and Child Welfare Centres y el 11.9% en las clínicas de Marie Stopes habían oído hablar de la regulación menstrual con medicamentos antes de recibir el servicio, comparado con un porcentaje mucho mayor (43%) en las unidades de salud rurales. En general, el 61.4% de las mujeres que reciberon medicamentos para la regulación menstrual encontraron que el método fue satisfactorio, y el 34.2% de ellas estaban muy satisfechas. Del 3.9% de las mujeres que no estaban satisfechas, la mayoría recibió servicios de unidades de salud rurales.

Despite a relatively high level of contraceptive use, Bangladesh still faces a high contraceptive discontinuation rate,Citation1 possibly resulting from a lack of sufficient information, knowledge and awareness about contraceptives.Citation2 As a result many women experience unwanted pregnancy and resort to various methods to terminate it and avoid the burden of an unplanned birth. In the late 1970s, the Government of Bangladesh approved menstrual regulation as an “interim method of establishing non-pregnancy” for women at risk of being pregnant, regardless of whether they were actually pregnant. Menstrual regulation in Bangladesh involves the use of manual vacuum aspiration up to ten weeks (paramedics are allowed to provide up to eight weeks) after the woman’s last normal menstrual period.Citation3 The service is now available throughout the country in more than 5,000 health facilities, provided primarily by Family Welfare Visitors at Union Health and Family Welfare Centres, Upazila Health Complexes, and Maternal and Child Welfare Centres.

The most recent estimate shows that approximately 650,000 induced abortions were carried out in Bangladesh in 2010, and a further 650,000 women underwent menstrual regulation at health facilities nationwide.Citation4 Because of the stigma, shame, and fear of social condemnation associated with abortion, women often turn to procedures that are ineffective, harmful and life threatening.Citation5 An underground network of unregulated menstrual regulation providers poses a major public health threat as the methods used are often ineffective and not medically safe. A situation analysis conducted in 2004 clearly documented the poor access of rural women to safe menstrual regulation services.Citation6 In addition, failure to train adequate numbers of menstrual regulation service providers to replace retiring providers has reduced access to safe menstrual regulation services in recent years. An in-depth study of induced abortion in rural Bangladesh in 2011 indicated that these barriers continue to exist, forcing poor women to use informal providers for health care services, including abortion.Citation7

A literature reviewCitation8 on the impact of menstrual regulation on reproductive health of women in Bangladesh in 1998 found that many women who were concerned that they may be pregnant but did not wish to undergo any procedure to end their pregnancy, instead sought drugs from pharmacies to induce menstruation. A rapid assessment conducted in 2009 by Marie Stopes Bangladesh in 62 pharmacies revealed that 51% of drug sellers knew of various drugs that are used to induce abortion, and 30% of drug stores and pharmacies were selling these to women.Citation9 The demand for an effective method of menstrual regulation that ensures privacy and confidentiality has led to calls for the introduction of mifepristone and misoprostol in the public sector in order that menstrual regulation can be undertaken in a non-invasive way. Misoprostol is a registered drug in Bangladesh, indicated for conditions other than abortion, and in 2013 mifepristone received approval to be imported or manufactured locally by the Bangladesh Drug Administration for use in medical menstrual regulation. The combination of the two drugs is already proven to be highly effective in many countries and is recommended by WHO in its Safe Abortion Guidance.Citation10 A study undertaken in Bangladesh has also established the effectiveness of medical menstrual regulation.Citation11 However, there has been no research in Bangladesh on the capacity of public sector providers, particularly mid-level providers in rural Bangladesh, to provide the service safely and effectively.

The current study examines the extent to which a package of interventions targeting providers in public and private clinics can enhance acceptability of medical menstrual regulation among women and also assess the extent of their satisfaction with the method. Comparisons are made between three different types of sites for medical menstrual regulation services: Maternal and Child Welfare Centres, Union Health and Family Welfare Centres, and Marie Stopes clinics. Marie Stopes is a non-governmental organization, while the first two types of sites are government operated. Maternal and Child Welfare Centres are primarily urban-based, and menstrual regulation is provided by physicians, while Union Health and Family Welfare Centres are rural-based and menstrual regulation is provided by Family Welfare Visitors, who are paramedics. The Marie Stopes clinics selected for the study are located in urban areas of Dhaka city, with services provided by physicians.

Methodology

Marie Stopes Bangladesh, in collaboration with the Population Council and the Directorate General of Family Planning, conducted an operations research study from January 2012 to June 2013. The study assessed whether medical menstrual regulation was acceptable to women as an alternative to manual vacuum aspiration. The facilities were selected to cover different categories of service providers, particularly in the public sector, where menstrual regulation services are widely available throughout Bangladesh. Fourteen study sites were purposively selected from eight districts of Dhaka Division in Bangladesh. Four Maternal and Child Welfare Centres in four urban districts, and eight Union Health and Family Welfare Centres in eight rural locations were also selected. The remaining two sites were urban-based Marie Stopes clinics. These facilities were selected based on the high turnover of menstrual regulation services and the availability of trained service providers who were willing to participate in the study. One of the urban-based government sites subsequently withdrew from the study when the only trained provider was transferred.

Thirty-two service providers including 11 doctors, 20 Family Welfare Visitors, and one Sub-Assistant Community Medical Officer (Medical Assistant) were selected to undergo training on medical menstrual regulation. They were chosen from among providers who had already been trained in manual vacuum aspiration and were currently providing the service. The curriculum for the training followed WHO guidance for medical abortion.Citation10 Service providers were interviewed before medical menstrual regulation training to assess their knowledge and attitude toward providing the services. Though 44 service providers from the selected facilities were interviewed before introducing medical menstrual regulation services, only 32 of them agreed to participate in training for the study.

The study population consisted of women who visited the 13 health facilities and received menstrual regulation services between October 2012 and May 2013. The criterion for enrolling women for the study was that their last menstrual period had started no more than eight weeks previously, which is in line with the regulations of the Bangladesh government for the paramedics and also as approved by the Bangladesh Medical Research Council for the study. The willingness of the women to participate in the study was ascertained and they were asked to provide informed consent. All participating women were given a choice between medical menstrual regulation and manual vacuum aspiration. They were provided with information and counselling on both methods following the WHO Safe Abortion guidance. The service providers were paid a small amount for providing the medical menstrual regulation to offset the money that they would get for manual vacuum aspiration; the amount was same for all the selected centres, both urban and rural.

A service guideline was developed adopting specific sections from WHO guidance for medical abortion and translated into Bangla in user-friendly language. The guidelines consisted of a counselling section, an examination section and the drug protocol for pregnancies up to eight weeks. The regimen was a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol as contained in Medabon, a combination pack of mifepristone 200 mg and misoprostol 800 mcg. The packs were donated by the Concept Foundation for the study. Women received the mifepristone orally on the first day at the health facility and were given a choice whether to use misoprostol at the health facility or at home. Women who preferred misoprostol administration at home were provided with four misoprostol tablets of 200 mcg each, along with necessary counselling and a pictorial pamphlet clearly showing how and when to use the tablets buccally. Women who preferred administration of misoprostol at the health facility were asked to return to the facility after 24–48 hours. All women were asked to return to the health facility 14 days after administering misoprostol for a follow-up visit. Women were also given a card with the telephone number of a call centre that was set up for the study. They were told to call if any assistance or advice was required. The call centre was functioning 24 hours a day to ensure women’s needs and safety.

A total of 2,976 women attended for menstrual regulation during the eight-month study period. Sixty-eight per cent attended an urban public health clinic, either the Maternal and Child Welfare Centres (27%) or Marie Stopes clinics (41%), while 32% attended Union Health and Family Welfare Centres. Research assistants were based at each of the study sites for interviewing women who opted for medical menstrual regulation and for other data collection. Women were interviewed immediately after the first dose of mifepristone and at the follow-up visit 14 days later. A total of 422 patient–provider interactions were observed by the research assistants using a standardized checklist to record their observations of medical menstrual regulation service quality. A composite quality score was calculated by measuring the performance according to set quality indicators. At the follow-up visit, the service providers confirmed the completeness of the process by performing a pelvic examination. If on examination, there were signs and symptoms of incomplete abortion, the women were treated with manual vacuum aspiration at the facility, or if required, were referred to a higher level facility.

Medical menstrual services were provided to 1,882 women, among whom 836 were interviewed: 253 from the urban government centres, 398 from rural government facilities and 185 from Marie Stopes clinics. The women selected for interview were chosen on the basis that they had agreed to the interview and agreed to return for follow up. In-depth interviews, using a semi-structured questionnaire, were used to assess their knowledge, attitudes and satisfaction before and after having medical menstrual regulation. Quantitative data were extracted from patient and service providers’ interviews and were analysed using SPSS. Appropriate statistical tests assessed whether the effect of the intervention was statistically significant.

Findings

Provider knowledge of medical menstrual regulation

From the providers pre-training interviews it was found that 32% of providers were not performing menstrual regulation with manual vacuum aspiration; the two most important reasons were personal (70%) and religious (20%) beliefs. Only one-fourth of all providers interviewed had heard of medical menstrual regulation, of which 75% mentioned that a longer duration of bleeding was an important disadvantage associated with medical menstrual regulation, while 100% of them said that instrumentation not being required for medical menstrual regulation was an advantage.

Acceptance of medical menstrual regulation

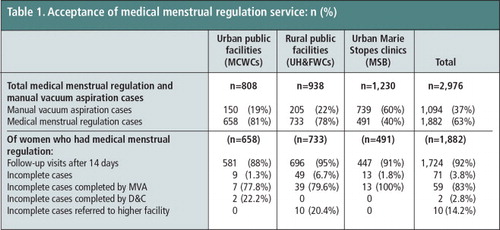

Table 1 shows that more women chose medical menstrual regulation (63%) than manual vacuum aspiration (37%). However, there were major differences between the sites, with the choice of the medical method being much higher in public facilities in urban (81%) and rural (78%) areas. The comparatively low acceptance of medical menstrual regulation at the Marie Stopes clinics is possibly a result of a higher proportion of working women attending the Marie Stopes clinics, with 29.7% of women who chose medical menstrual regulation working, compared to only 6.8% women at Maternal and Child Welfare Centres and 10.1% in Union Health and Family Welfare Centres (data not shown). Working women may have wanted to have the process completed at a single visit. Ninety-two per cent of the women receiving the medical method returned for follow-up. The percentage was slightly higher in rural areas (95%) because the study was supported by the Family Welfare Assistants (government cadre of field workers) in the rural areas, who ensured that the women returned.

Medical menstrual regulation was found to be highly effective, with only 71 (3.8%) women requiring further treatment after administration of the drugs. Of the 71 women who were categorized as having incomplete abortions, nine had attended Maternal and Child Welfare Centres, 49 had attended the Union Health and Family Welfare Centres and 13 the Marie Stopes clinics. Fifty-nine of the 71 women had subsequent manual vacuum aspiration. Two had dilatation and curettage (D&C) to evacuate the uterus, and ten women attending a rural centre were referred to higher facilities supported by doctors.

Knowledge of medical menstrual regulation and its side effects

The interviews undertaken with women before they received counselling on menstrual regulation methods showed that only 7.1% of those who attended maternal and child welfare centres and 11.9% of those who attended Marie Stopes clinics knew of medical menstrual regulation, compared to a higher proportion (43%) of women who attended services in rural centres. Rural women were more aware of medical menstrual regulation because the Family Welfare Assistants who work in rural areas disseminated information about it within the community; therefore many women coming to these centres were already aware of the method. Of the women who knew about medical menstrual regulation, only 208 women responded to the question on possible side effects of the medications – 18 from the Maternal and Child Health Centres, 21 from the Marie Stopes clinics and 169 from the rural centres.

Almost all the women mentioned the intended effect of bleeding after taking the misoprostol (57%) or passage of blood clots (47%). Among the usual side effects, the most commonly mentioned was abdominal cramps (43%). Other side effects mentioned included fever/chills (57.7%), nausea (54.8%), vomiting (54.3%), diarrhoea (35.6%), dizziness (23.6%) and headache (19.2%). When pressed further on their knowledge of potential complications resulting from the medications, 44.5% of the 208 women mentioned heavy bleeding, 34.4% mentioned heavy and prolonged bleeding, 25.8% mentioned severe cramping followed by fever and chills persisting for six or more hours (24.9%), while abnormal vaginal discharge was mentioned by 13.9%, and severe abdominal pain by 11%. A comparatively large proportion (40.2%) did not have any knowledge of the expected complications.

Side effects experienced by women using medical menstrual regulation

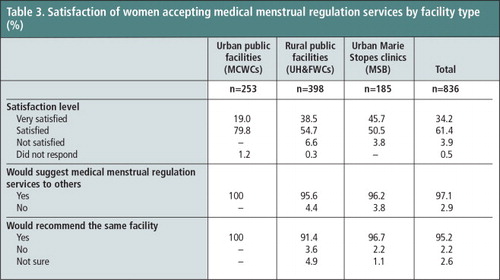

Side effects experienced by the women after medical menstrual regulation are presented in Table 2 , by type of health facility. Sixty-seven per cent of women experienced side effects after taking misoprostol. Commonly cited side effects of misoprostol experienced were fever or chills (54%), nausea (40%), vomiting (28%), headaches (23%), diarrhoea (15%) and dizziness (14%). Thirty-six per cent of the women experiencing these needed medication to treat them.

Table 2 Percentage distribution of women using medical menstrual regulation who reported side effects after misoprostol (%).Footnotea

During the study period 622 calls were received at the call centre, of which 77% were from the women who had used medical menstrual regulation, while 20% came from women’s husbands. The remainder of the callers declined to disclose their identity. About 69% of the women called after taking misoprostol, while 31% called after taking mifepristone. About 97% of the calls were because the woman was experiencing one or more of the usual side effects and was enquiring about remedies.

Satisfaction with medical menstrual regulation

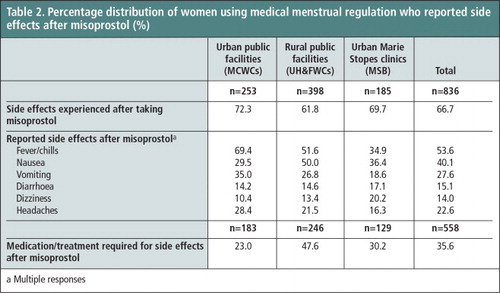

Interview findings show that women were satisfied with medical menstrual regulation services (Table 3). Nearly two-thirds found the service satisfactory, and one-third were very satisfied. There was not a significant difference in satisfaction level by type of facility. In fact, 97% reported that they would suggest the medical menstrual regulation service to others, and 95% would refer a friend to the same health facility.

The overall composite quality score for all health facilities was 0.80 (out of a total of 1.00), signifying that the quality of medical menstrual regulation services provided was acceptable. The Union Health and Family Welfare Centres scored 0.73, the Maternal and Child Welfare Centres scored 0.85 and the Marie Stopes clinics scored 0.88.

Discussion

The menstrual regulation programme in Bangladesh has earned a reputation for providing services that have contributed to lowering the level of unplanned pregnancies. The public sector, being the largest provider of health care, has to function with major resource constraints and thus faces many difficulties, while the private and the non-governmental organizations that provide menstrual regulation services have more freedom in the way they function. One of the difficulties of providing menstrual regulation services is that many women do not wish to undergo manual vacuum aspiration, when it is the only method offered. Medical menstrual regulation, as shown in this study, is another option, which has been shown to be equally effective and less invasive, and about which there is a high level of knowledge and acceptance. Thus, it is feasible to introduce the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol in the national programme. The study purposively selected health facilities with different types of service providers from both urban and rural districts throughout Dhaka Division, to better understand the challenges and potential barriers to implementing medical menstrual regulation as part of the national family planning strategy.

Given the option between standard menstrual regulation with manual vacuum aspiration and medical menstrual regulation, 63% of women selected the medical method, and most of them were satisfied with the drug regimen. The health facilities participating in this study overall showed a good quality of care based on the composite quality score. The success or failure of medical menstrual regulation service should not be attributable to the drug administration alone; however, comprehending the entire procedure by women from different socio-demographic strata is important. The most important part of this service is counselling and the capacity of the women to understand and cope with the possible side effects, and this should be given major consideration during counselling so that women can manage the side effects, any complications, and the entire procedure.

This study shows that there is a demand from women for medical menstrual regulation services, and that it can easily be introduced in both rural and urban facilities. Currently, a large number of providers do not offer menstrual regulation services as an alternative to manual vacuum aspiration for personal reasons. Unfortunately, if trained service providers for menstrual regulation are not available in a clinic or geographical area, women who are aware it exists may well continue to seek the medical method from informal providers. To avoid this, medical menstrual regulation as an alternative to manual vacuum aspiration should be incorporated widely into primary level health care.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the technical and financial support from HRP (UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction).

Notes

a Multiple responses

References

- National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. 2013; NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International: Dhaka and Calverton, MD.

- UN Population Fund. Bangladesh Population Policy: Emerging issues and future agenda, CPD-UNFPA Paper Series 23; 1997.

- Guttmacher Institute. Menstrual regulation and induced abortion in Bangladesh. Fact sheet, September 2012.

- S Singh, A Hossain, I Maddow-Zimet. The incidence of menstrual regulation procedures and abortion in Bangladesh. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 38(3): 2012; 122–132.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates and associated mortality. 6th ed., 2008; WHO: Geneva.

- SNM Chowdhury, D Moni. A situation analysis of the menstrual regulation programme in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24/Suppl.): 2004; 95–104.

- S Ahmed, A Islam, PA Khanum. Induced abortion: what’s happening in rural Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters. 7(14): 1999; 19–29.

- N Piet-Pelon. Menstrual regulation impact on reproductive health in Bangladesh: a literature review. Regional Working Papers No. 14. 1998; Population Council: Dhaka.

- KG Rasul. Know your market: short field survey on pharmacies. 2009; Marie Stopes Bangladesh: Dhaka.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2nd ed., 2012; WHO: Geneva.

- U Rob, IA Hena, N Sultana. Introducing medical menstrual regulation in Bangladesh. 2013; Population Council, Marie Stopes Bangladesh and Directorate General of Family Planning: Dhaka.