Abstract

The context of sexual relations is changing in the Asia-Pacific. While the age of sexual debut remains the same, young people are generally marrying later and sex outside of marriage is increasing. The first systematic review of how laws and policies govern young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services was conducted in 2013. The study considered >400 national documents and held focus group discussions with >60 young people across three countries in the region. This paper examines the study findings in light of epidemiological data on young people’s sexual behaviour and health, exposing a critical mismatch between the onset of sexual activity and laws and policies governing consent (to sex and medical treatment), and the restriction and orientation of services to married persons. An enabling legal and policy environment is an essential foundation for efforts to improve young people’s sexual and reproductive health. This paper argues that international guidance and commitments (including the widely ratified Convention on the Rights of the Child) provide a framework for recognising young people’s evolving capacity for independent decision-making, including in the realm of sexual and reproductive health. A number of countries in the region are using these frameworks to expand access to services, providing valuable examples for others to build on.

Résumé

Le contexte des relations sexuelles évolue en Asie et dans le Pacifique. Si l’âge des premiers rapports reste le même, les jeunes se marient généralement plus tard et les rapports sexuels en dehors du mariage sont plus fréquents. La première étude systématique de la manière dont les lois et politiques régulent l’accès des jeunes aux services de santé sexuelle et génésique a été réalisée en 2013. Elle a examiné >400 documents nationaux et organisé des discussions de groupe avec >60 jeunes dans trois pays de la région. Cet article examine les conclusions de l’étude à la lumière des données épidémiologiques sur le comportement sexuel et la santé des jeunes. Il expose une grave inadéquation entre le début de l’activité sexuelle et les lois et politiques régissant le consentement (aux relations sexuelles et au traitement médical) et les services réservés ou s’adressant aux personnes mariées. Un environnement juridique et politique habilitant est un fondement essentiel des activités d’amélioration de la santé sexuelle et génésique des jeunes. L’article avance que les directives et instruments internationaux (notamment la Convention relative aux droits de l’enfant largement ratifiée) fournissent un cadre pour reconnaître l’évolution de la capacité des jeunes à prendre des décisions indépendantes, notamment dans le domaine de la santé sexuelle et génésique. Plusieurs États de la région se servent de ces cadres pour élargir l’accès aux services, fournissant des exemples précieux dont peuvent s’inspirer d’autres pays.

Resumen

El contexto de las relaciones sexuales está cambiando en Asia-Pacífico. Aunque la edad para la iniciación sexual continúa siendo la misma, por lo general las personas jóvenes se están casando más tarde y el sexo extramatrimonial está en alza. En 2013 se realizó la primera revisión sistemática de cómo las leyes y políticas rigen el acceso de las personas jóvenes a los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva. El estudio consideró >400 documentos nacionales y llevó a cabo discusiones en grupos focales con >60 personas jóvenes en tres países de la región. Este artículo examina los hallazgos del estudio en vista de los datos epidemiológicos sobre el comportamiento sexual y la salud de las personas jóvenes, y expone una discordancia crítica entre la iniciación de la actividad sexual y las leyes y políticas que rigen el consentimiento (para las relaciones sexuales y el tratamiento médico), y la restricción y orientación de los servicios a las personas casadas. Un ambiente legislativo y político facilitador es una base esencial para los esfuerzos por mejorar la salud sexual y reproductiva de las personas jóvenes. Este artículo argumenta que las guías y compromisos internacionales (incluida la muy ratificada Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño) ofrecen un marco para reconocer la capacidad evolutiva de las personas jóvenes para tomar decisiones independientemente, incluso en el campo de salud sexual y reproductiva. Varios países en la región están utilizando este tipo de marco para ampliar el acceso a los servicios, proporcionando valiosos ejemplos en los que se pueden basar otros países.

The Asia-Pacific region is home to 750 million young people aged 10–24,Footnote* the largest youth cohort in history.Citation1 While these young people are generally healthier and better educated than in the past, progress in relation to their sexual and reproductive health is lagging.Citation2 Poor access to services, information, and commodities such as contraceptives and condoms, contributes to high levels of unplanned pregnancy and the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. There are nearly six million adolescent pregnancies and over one million unsafe abortions in girls aged 15–19 in the Asia-Pacific each year.Citation3 In 2013, 610,000 young people in the Asia-Pacific (aged 15–24) were living with HIV and every year 58,000 adolescents in the region are newly infected with HIV.Citation4,5

Young people face multiple and intersecting barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health services. The sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people necessarily interrogate complex and contested notions of childhood, development and sexuality bound up in very personal understandings of the roles and responsibilities of parents.Citation6–8 These ideas inform the many possible interpretations of what constitutes “the best interests of the child” in the context of sexual and reproductive health.Citation9 This paper adopts the fundamental principle that in this context, the best interests of the child must recognise young people’s right to the “highest attainable standard of health”.Citation10 Realising this right requires access to services based on need; while removing legal and policy barriers alone will not be sufficient, it is a foundational step.

The first systematic review of the laws and policies that govern young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services in the Asia-Pacific region was conducted in 2013. Entitled Young people and the law in Asia and the Pacific: A review of laws and policies affecting young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health and HIV services, it considered over 400 national documents.Citation2 Focus group discussions were held with more than 60 young people (aged 18–24) in Jakarta, Indonesia, Manila, Philippines and Yangon, Myanmar, using a standardised guide and participatory methods (including brainstorming and ranking), facilitated by Youth LEAD, a regional network of young people from key populations. Particular focus was given to the impact on access to services of laws and policies that require people to be of a certain age for various purposes.

This paper examines the findings of that study in light of epidemiological data on the sexual behaviour and health of young people, exposing a critical mismatch – between the onset of sexual activity, laws governing consent (to sex and medical treatment), and the restriction and orientation of services to married persons. We argue that international guidelines and commitments provide a conceptual and increasingly practical framework for law- and policy-makers seeking to reconcile efforts to protect young people from abuse and ensure their rights to health and autonomy. The analysis concludes by considering the application of these frameworks to expand access to services in the region.

Young people and sex in the Asia-Pacific region

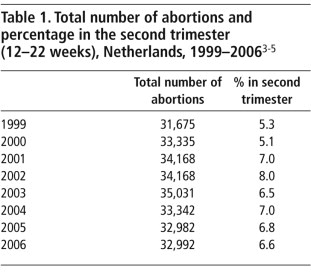

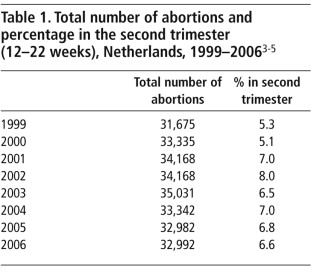

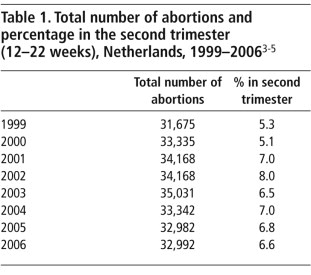

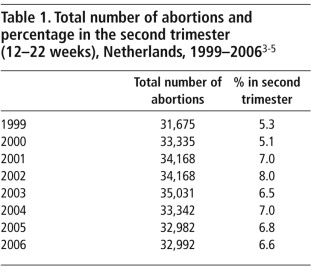

Young people in the Asia-Pacific, both married and unmarried, are sexually active and many are first having sex under the age of 18 years (see ). As many as 40% of young women in India aged 18–24 and almost as many young women of the same age in Indonesia and Nepal first had sex before turning 18.Citation11 Corresponding numbers for boys are lower but still significant. In Lao PDR, 28% of young men aged 18–24 report that they first had sex when they were under 18,Citation12 as do 26% and 24% of young men from the same age group in Thailand and Nepal, respectively.Citation13,11 A 2006 study of young people aged 15–24 in Samoa, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu found that the median age at first sex was 16.Citation14Footnote*

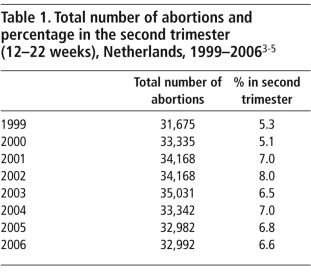

Table 1 Percentage of young men and women who first had sex under 18 years of age.Citation11,15

For most young people in the region (particularly young women) the onset of sexual activity still coincides with marriage;Citation15 many of the countries in which young people initiate sexual activity before turning 18 are also countries with high rates of child marriage.Citation16 The age of marriage is, however, rising. A comparison of data from 1970 to 2010 shows that the average age of marriage has increased in South, East and South-East Asia, even in countries where child marriage remains common (see ).Citation17 While data on the sexual activity of unmarried young people is limited, studies in Cambodia,Citation18 the PhilippinesCitation19 and ThailandCitation20 indicate that an increasing number of unmarried young people are having sex and that sex outside of marriage becomes more likely with increasing age.Citation15 As the incidence of child marriage decreases, more young people who start having sex before turning 18 will be doing so outside of marriage and outside the protections many countries reserve for married couples.

The review found that services are heavily oriented to the needs of married couples throughout much of the region and create barriers to access for people under 18 years of age.Citation2Footnote* In this legal and policy environment, the changing context of marriage and sexual relations has serious consequences for young people.

Table 2 Average age of marriage of women and men in South, East and South-East AsiaCitation17,21

Data on the unmet need for contraception among unmarried young women,Footnote† particularly those under 18 years, is extremely limited.Citation15 Unmet need for contraception among young women who are married or in a long-term union is, however, 25-30% in a number of countries in the region,Citation2Footnote** and as high as 46% in Samoa.Citation22 This suggests that unmet need among unmarried young women is also high. Less than 20% of young people aged 15–19 in the Pacific report ever having used a modern method of contraception.Citation14 The Viet Nam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (2011) found that 30.5% of married and 35.4% of unmarried young people aged 15–19 had an unmet need for contraception; for 20–24 year-olds the percentages were 19.0% (married) and 34.6% (unmarried).Citation23

A recent study by the Population Council found extremely low levels of consistent condom use among unmarried young men and women aged 15–19 and 20–24 in India, and that a significant minority of unmarried girls fall pregnant.Citation24 A 2006–2007 study found that 4% of unmarried young men and 9% of unmarried young women who had sex with a “romantic partner” reported a pregnancy.Citation25 Another Indian survey, among sexually experienced college students in Gujarat, found that 17% of the young men had made a girl pregnant and 8% of the young women had experienced a pregnancy.Citation26 While a percentage of these pregnancies may have been wanted, the findings are indicative of an unmet need for information, contraception, safe abortion and broader health and information services. Sexual activity among young people under 18 and the changing context of sexual relations requires laws and policies that support access to life-saving and life-enhancing sexual and reproductive health services.

Laws, policies and barriers: age, marital status and consent issues

Sexual and reproductive rights “embrace certain human rights that are already recognised in national laws, international human rights documents and other consensus documents”.Citation27 In addition to reiterating the right of all people to the “highest attainable standard of physical and mental health” under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),Citation10 the Convention on the Rights of the Child requires States parties to “strive to ensure that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to… health care services” including “preventive health care, guidance for parents and family planning education and services”.Citation9 Under Article 16, “no child shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy”. All UN member states in the Asia-Pacific have ratified, accepted, or acceded to this Convention, and most have also signed or ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.Citation2

Young girls waiting in their boats to ferry passengers across the river, Phuong Hiep, Viet Nam, 2005

Despite their international commitments, many countries in the Asia-Pacific region have laws and policies that limit access to sexual and reproductive health services. In 2012 the Commission on Population and Development used its Resolution on Adolescents and Youth to urge governments to protect and promote human rights “regardless of age and marital status”.Citation27 Yet, as we show here, there is a mismatch between laws and policies that limit access to sexual and reproductive health services, the age of consent to sex and the age at which young people are initiating sexual activity.

Consent to medical interventions

In most countries in the Asia-Pacific, a person gains the legal capacity to independently consent to medical interventions at the age of 18.Citation2 Young people under 18 years of age therefore, generally require parental consent to access sexual and reproductive health services. This creates a barrier for young people who are unable or unwilling to seek parental consent, and for those young people whose parents refuse consent when asked.

Laws in some countries, including customary or religious laws, also require young people to seek consent from people other than their parents, including spouses, extended family or elders, and religious leaders.Citation2 An analysis of shari’a law in Malaysia found that spousal or parental consent to medical interventions may be required for young people under 18 years of age.Citation28 This undermines young people’s right to privacy and denies them autonomy to make decisions about their own well-being.

Even where laws support access, policy and implementation at the clinic level may create barriers. Sri Lankan law recognises that boys aged 16 years and girls aged 14 years are “competent to exercise choices in personal decisions affecting their lives”;Citation29 however medical practitioners often administer forms requiring parental consent.Citation30 Participants in a focus group discussion conducted in Myanmar as part of the Young people and the law review reported HIV testing being refused to a 14-year-old on the basis that he was “too young”, despite legislation requiring parental consent only for children under 12.Citation2 Thus, while access may be more or less restricted than the text of the law suggests, young people’s rights are rarely guaranteed and often subject to gate-keeping by health care practitioners. Access may be further restricted for young people unable to prove their age. Conflicting laws, policies and practice confuse the limits on access to services and in some instances promote cautious interpretation likely to overstate the limits, both among practitioners concerned with acting within the law and young people already hesitant to expose themselves to the stigma associated with youth sexuality.

Marriage as a requirement to access services

Marriage is only a precondition for access to services in one country in the region, Indonesia;Citation31 however, sexual and reproductive health services are often heavily oriented to the needs of married couples, sometimes with the practical effect that services are not provided to unmarried young people. Government and NGO clinics in Malaysia, for example, provide sexual and reproductive health services to unmarried persons only on a case-by-case basis, to young people they consider to be at high risk.Citation32 Under China’s Family Planning Law, only “couples of reproductive age” are able to obtain services through public facilities without charge.Citation33 Indonesia’s national family planning policy includes only “candidate (betrothed) or husband-wife couples”.Citation31 The effect of these policies is that for many unmarried young people, access to sexual and reproductive health services is either subject to the approval of health care practitioners or the ability to pay for services through private clinics.

Age of consent to sex

While most countries in the region do not allow young people to marry or independently consent to medical interventions until they are 18 (see ), legislation in many countries recognises that young people can legally consent to sex from a younger age. Young people can, for example, consent to sex from the age of 12 in the Philippines,Citation34 14 in China,Citation35 15 in Thailand,Citation36 and 16 in Malaysia.Citation37 Where the age of consent to sex is lower than the age of consent to medical interventions, however, young people considered old enough to consent to sex may find themselves unable to access the sexual and reproductive health services they need when they do have sex.

The critical mismatch between law, policy and reality

sets out the ages of consent to sex and marriage in six Asia-Pacific countries where young people under 18 require parental consent for medical interventions. The table clearly indicates the extent of the mismatch between services available under restrictive laws and policies and the reality of young people’s sexual and reproductive health needs.

While the age of independent consent to marriage is 18 years or older in the majority of countries in Asia-Pacific, in practice, many countries allow marriage at a much younger age with parental consent or with the endorsement of the courts or religious or local government authorities.Citation2

What governments can do

Young people under 18 years of age present a “unique dichotomy” for law- and policy-makers who must codify protections in the shifting context of the evolving capacities of the child.Citation8 Capacity for independent decision-making increases with the “developmental changes that children experience as they mature, including progress in cognitive abilities and capacity for self-determination”.Citation2 As children’s capacities increase, the need for guidance decreases and must be replaced with the obligation to allow young people the autonomy to make decisions about their own well-being. Under the Convention, these dual obligations are not competing but “mutually reinforcing”.Citation7,8 While implementation remains a challenge,Citation6 international guidelines and commitments provide a conceptual and increasingly practical framework for health care practitioners and law- and policy-makers wrestling with “the classic dilemma between… empowering and controlling, [and] balancing the roles of carer, protector, advocate and liberator”.Citation38

Governments can ensure that marriage requirements and age of consent laws do not adversely affect access to services by adopting a needs-based approach through the laws and policies that govern sexual and reproductive health services. The age of consent to sex, including in same-sex relationships, and the age of consent for autonomous access to sexual and reproductive health services, should be set at an age that recognises many young people commence sexual activity before turning 18. Consensual sexual activity between young people who are similar in age should also not be criminalized. Instead, governments need to ensure that young people have access to the information and commodities that they need for safer sex – from sexuality education to condoms and contraceptives, the vaccine against human papillomavirus that also prevents genital warts, and screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, including confidential HIV testing and treatment. Lastly, consideration should be given to ensuring that the age of consent for autonomous access to sexual and reproductive health services is consistent with the age of consent for sexual relations.

In enforcing 18 years as the minimum legal age for marriage, governments must not also raise the age of consent to sex in the unfounded hope that young people would delay having sex accordingly. Nor should governments reduce protections against child marriage by lowering the minimum marriageable age, as is currently being discussed in Bangladesh,Citation39 contrary to international human rights law.Citation16,40

Recognise and allow for the evolving capacities of the child

The Convention on the Rights of the Child establishes the principle that the best interests of the child shall be “a primary consideration in all actions concerning children”.Citation9 Inherent in this concept is the recognition of the rights outlined by the Convention, including the right to health, and the right of children to have their views given due weight in accordance with their age and maturity. Article 5 states that:

“States Parties shall respect the responsibilities, rights and duties of parents [and others legally or customarily responsible for the child]… to provide, in a manner consistent with the evolving capacities of the child, appropriate direction and guidance in the exercise by the child of the rights recognised in the present Convention”.Citation9

International guidance is increasingly recognising that in the context of sexual and reproductive health, the best interests of the child may require allowing a young person to access certain services based on need, without parental consent. In its General Comment 15, the Committee on the Rights of the Child confirmed that children’s evolving capacities have a bearing on their ability to make decisions about their own health, recognising the sui generis nature of barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health services. The Committee noted that:

“States should review and consider allowing children to consent to certain medical treatments and interventions without the permission of a parent, caregiver, or guardian, such as HIV testing and sexual and reproductive health services, including education and guidance on sexual health, contraception and safe abortion”.Citation41

The World Health Organization (WHO) Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Diagnosis and Care for Key Affected Populations, released in July 2014, echo that approach. The guidelines recommend that sexual and reproductive health services, including contraceptive information and services, be provided to adolescents without requiring parental consent and state that:

“To act in the best interest of adolescents, health services may need to prioritize their immediate health needs, while being attentive to signs of vulnerability, abuse and exploitation. Appropriate and confidential referral, if and when requested by the adolescent, can provide linkages to other services and sectors for support.”Citation42

Analysis of recent law and policy reform in the region

A number of countries in the region have applied international guidance in recent law and policy reform. Some show fidelity to the international rights framework and are likely to have a positive impact on young people’s access to services. Others may be imperfect, but are at least a first step.

The mature minor principle or “Gillick competency”

Many countries (including Australia, Fiji and New Zealand in the Asia-Pacific region) apply the concept of the evolving capacities of the child to determine whether a young person under 18 can make health care decisions independently, through what is called the mature minor principle or “Gillick competency”.Footnote* The principle allows minors to consent to medical procedures independently where they are “judged by a health professional to be sufficiently mature to understand the meaning and consequences of the procedure”.Citation2 Where a minor is considered to lack capacity to consent independently, a parent or guardian is asked.

While the mature minor principle may allow the flexibility inherent in the concept of the evolving capacities of the child, it elevates age above other measures of decision-making competency by requiring additional scrutiny of all young people under 18 years of age. Young people under 18 may still be refused services. By requiring practitioners to decide whether a young person has the capacity to consent, the principle makes young people’s sexual and reproductive health rights subject to the views of the health care practitioner. To make this judgement, medical practitioners need to be educated about their legal responsibilities and provided with operational guidance for the implementation of such laws.

Laws specifying an age of consent to HIV testing under 18 years

A growing number of countries in the Asia-Pacific are expanding young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services by lowering the age for independent consent to HIV testing below 18 years (see ). While such laws lack flexibility, they recognise that young people may develop the capacity for independent decision-making in relation to certain matters before turning 18, consistent with recommendations by the WHO and Committee on the Rights of the Child. These laws, however, do not extend to broader sexual and reproductive health services, including those necessary to prevent the spread of HIV. Young people seeking those services may still require parental consent.

Table 4 Legal age of independent consent to HIV testing below 18 yearsCitation2Citation43.Citation44

An alternative to parental consent

In the Philippines an Administrative Order provides for a social worker or counsellor to permit HIV testing for a person under 18. This policy is not always applied, however. Young people participating in a Philippine focus group discussion as part of the review described above reported that counsellors are often unavailable or still ask for parental consent, saying that it is legally required.Citation2 Where implemented, the policy has been effective, even though the Administrative Order does not allow the autonomy to consent independently.Citation45

The strict legal position in relation to other medical interventions in the Philippines establishes that parental consent must be given for persons younger than 18 except in emergency situations.Citation46 An exception was introduced in 2013 to allow young people under 18 to access family planning services if they were already a parent or had previously had a miscarriage.Citation47 The provision was, however, declared unconstitutional by the country’s Supreme Court in 2014.Citation48 New laws are also proposed to allow young people aged 15–17 to independently consent to an HIV test if they are assessed to be at high risk of HIV.Citation49

Access to services based on need

New Zealand has adopted a more comprehensive approach to ensuring young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health services. Minors in New Zealand are able to access contraceptive and abortion services without parental consent based on need, overcoming the deterrent impact of requiring disclosure to and consent from parents. Consent to other medical services is determined according to the mature minor principle for young people under 16 years.Citation50 Those over 16 years can consent independently.

The New Zealand policy is in line with the recommendations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, that States should allow children to consent to certain medical interventions without the permission of a parent. Typically, the mature minor principle provides scope for children to consent to such services where a health care practitioner judges the child to be of sufficient maturity. New Zealand’s sexual and reproductive health policy goes further, however, in that it adopts a needs-based approach without reference to the views of the medical practitioner. While this does not ensure against the denial of services by individual practitioners, it makes clear that young people have a right to access such services, regardless of the practitioner’s views.

Conclusion

Realising the right to the highest attainable standard of health for young people, as for adults, requires access to services based on need. Removing legal and policy barriers is therefore essential, both as a first step toward expanding access to sexual and reproductive health services and in defining the “best interests of the child” in this controversial context. A growing number of countries are now using international guidelines and commitments to improve access to services through law and policy reform. To create an environment in which young people are enabled to protect their own well-being, law- and policy-makers must build on these examples, acknowledging both their shortcomings and the progress they represent.

Notes

* This paper uses the terms "adolescents" (10–19 years) and "young people" (15–24 years), consistent with definitions used by the United Nations. The term “child” (under 18 years) is also used to refer to this age group.

* Many surveys, including Demographic and Health Surveys, use a narrow definition of sexual activities and do not capture the broader range of sexual activities, including oral and anal sex, that young people may engage in from a young age.

* A list of national laws, policies and strategies considered is available at Annex VII of the review.Citation2

† Those who wish to stop or delay childbearing.

** Afghanistan, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste, and Tuvalu.Citation2

a Familial consent may still be required.

b Laws differ in Aceh province, where sex before marriage and same-sex conduct are prohibited.

c Despite guidelines recognising the value of anonymous voluntary counselling and testing for young people.

* Named after the UK House of Lords judgment Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority [1986] 3 All ER 402 (Lord Scarman).

References

- United National Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Social Development in Asia and the Pacific. Youth. http://www.unescapsdd.org/youth

- UNESCO UNFPA UNAIDS UNDP Youth LEAD. Young people and the law in Asia and the Pacific: A review of laws and policies affecting young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health and HIV services. Bangkok; 2013. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002247/224782E.pdf

- IH Shah, E Åhman. Unsafe abortion differentials in 2008 by age and developing country region: high burden among young women. Reproductive Health Matters. 20(39): 2012; 169–173. 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39598-0.

- UNAIDS. HIV and AIDS Data Hub for Asia Pacific. Estimated number of young people (15–24) living with HIV, 1990–2013, Asia and the Pacific. Based on UNAIDS 2014 estimates. Forthcoming.

- B Schunter. Lessons learned from a review of interventions for adolescent and young key populations in Asia Pacific and opportunities for programming. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 66: 2014; 186–192. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000185.

- H Montgomery. Buying innocence: child sex tourists in Thailand. Third World Quarterly. 29(5): 2008; 903–917. 10.1080/01436590802106023.

- International Planned Parenthood Foundation. How do we assess the capacity of young people to make autonomous decisions? Understanding young people’s right to decide. 2012; IPPF: London. www.ippf.org/system/files/ippf_right_to_decide_05.pdf.

- UNESCO UNAIDS UNFPA UNICEF WHO. Young people today, time to act now – Why adolescents and young people need comprehensive sexuality education and sexual and reproductive health services in Eastern and Southern Africa (Summary). Paris, 2013. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002234/223447E.pdf

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577. http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html.

- UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 16 December 1966, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 993. http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36c0.html.

- R Anderson, C Panchaud, S Sing. Demystifying Data: A Guide to Using Evidence to Improve Young People’s Sexual Health and Rights. Sexual and Reproductive Health – Sexual Activity and Marriage. 2013; Guttmacher Institute: New York. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/demystifying-data.pdf.

- Ministry of Health and Lao Statistics Bureau. Lao Social Indicator Survey (MICS/DHS) 2011–2012. http://www.nsc.gov.la/nada/index.php/catalog/17

- Thailand National Statistical Office. Thailand Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2005–2006. http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/27

- New Zealand Parliamentarians’ Group on Population and Development. Pacific Youth: Their Rights, Our Future: Report of an Open Hearing on Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in the Pacific (Bookshelf). Reproductive Health Matters. 21(41): 2013; 262–264. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41705-6.

- Burnet Institute. Sexual and reproductive health of young people in the ASEAN region – A review of issues, policies and programs. Forthcoming.

- UNFPA. Marrying Too Young – End Child Marriage. New York; 2012. http://www.unfpa.org/public/home/publications/pid/12166

- GW Jones. Changing Marriage Patterns in Asia. Asia Research Institute Working Paper No. 131. Singapore; 2010. http://www.ari.nus.edu.sg/docs/wps/wps10_131.pdf

- R Hong, V Chhea. Changes in HIV-related knowledge, behaviors, and sexual practices among Cambodian women from 2000 to 2005. Journal of Women’s Health. 18(8): 2009; 1281–1285. 10.1089/jwh.2008.1129.

- UD Upadhyay, MJ Hindin. The influence of parents’ marital relationship and women’s status on children’s age at first sex in Cebu, Philippines. Studies in Family Planning. 38(3): 2007; 173–186. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00129.x.

- A Powwattana. Sexual behavior model among young Thai women living in slums in Bangkok, Thailand. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health/Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium for Public Health. 21(4): 2009; 451–460. 10.1177/101053950934397.

- World Bank. Age at first marriage. Demographic and Health Surveys. http://data.worldbank.org/

- Kantorova L Alkema, V Menozzi. National, regional and global rates and trends in contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning between 1990 and 2015: a systemic and comprehensive analysis. Lancet. 11(381): 2013; 1642–1645. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62204-1.

- Viet Nam Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2011. http://www.gso.gov.vn/default_en.aspx?tabid=515&idmid=5&ItemID=12491.

- KG Santha, SJ Jejeebhoy. The sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people in India: a review of the situation. New Delhi, 2012. http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2012PGY_IndiaYouthSRHandRights.pdf

- International Institute for Population Sciences and Population Council. Youth in India: Situation and Needs 2006–07. Mumbai, 2010. http://www.macfound.org/media/article_pdfs/2010PGY_YouthInIndiaReport.pdf

- R Sujay. Premarital sexual behaviour amongst unmarried college students of Gujarat, India, Health and Population Innovation Fellowship Programme Working Paper No. 9. New Delhi, 2009. http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/wp/India_HPIF/009.pdf

- UN Commission on Population and Development. Resolution on Adolescents and Youth. New York, 2012. http://www.un.org/popin/icpd/conference/offeng/poa.html

- A Nga. The position of consent under Islamic law. International Medical Journal. 4(1): 2005; 1.

- Government of Sri Lanka. Second Periodic Report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, CRC/C/70/Add.17. New York, 2002. http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ecb93274.html

- World Health Organization. Using Human Rights to Advance Sexual and Reproductive Health of Youth and Adolescents in Sri Lanka. Colombo, 2012.

- Indonesia. Law Concerning Population and Family Development, 2009.

- R Abdullah. Increasing access to the reproductive right to contraceptive information and services, sexual and reproductive health rights, education for youth and legal abortion. 2009; Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women: Kuala Lumpur. http://arrow.org.my/publications/ICPD+15Country&ThematicCaseStudies/Malaysia.pdf.

- Population and Family Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China, 1981.

- Revised Penal Code of the Philippines. http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/text.jsp?file_id=225305.

- Criminal Law of China 1977. http://www.china.org.cn/english/government/207320.htm.

- Criminal Code of Thailand. http://www.thailandlawonline.com/laws-in-thailand/thailand-criminal-law-text-translation.

- Penal Code of Malaysia. www.agc.gov.my/Akta/Vol.%2012/Act%20574.pdf.

- S Banks. Ethical Issues in Youth Work. 1999; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Human Rights Watch. Bangladesh: don’t lower marriage age – ending child marriage should include support for victims, at-risk girls. 2014. http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/12/bangladesh-don-t-lower-marriage-age

- UN General Assembly, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. 18 December 1979, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1249. http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3970.html.

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, General comment No. 15 (2013) on the right of the child to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health (Art. 24), 17 April 2013. http://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9e134.html.

- WHO. Comprehensive guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. Geneva, 2014. http://who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/keypopulations/en/

- Indo-Asian News Service, DNA India. Demand for passage of pending HIV/AIDS bill across India. 2 December 2013. http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-demand-for-passage-of-pending-hivaids-bill-across-india-1928402

- Senate of Philippines – 16th Congress. Revised Philippine HIV and AIDS Policy and Program Act of 2013. http://www.senate.gov.ph/lis/bill_res.aspx?congress=16&q=SBN-1100.

- Department of Social Welfare and Development, Administrative Order, 2003 (Philippines).

- An Act Lowering the Age of Majority from Twenty-one to Eighteen Years, Amending for the Purpose of Executive Order Numbered 209 and for Other Purposes, Republic Act No. 06809 (Philippines) http://www.youthpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/library/1989_Act_Lowering_Majority_Age_Philippines.pdf.

- Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012, Philippines. http://www.gov.ph/2012/12/21/republic-act-no-10354/.

- Imbong v. Ochoa (2014) Republic of the Philippines Supreme Court. http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/microsite/rhlaw/.

- The Revised Philippine HIV and AIDS Policy and Program Act of 2012 (HB 6751). http://www.pnac.org.ph/uploads/documents/about-pnac/RA8504.pdf.

- Ministry of Health New Zealand. Consent in Child and Youth Health: Information for Practitioners. Wellington, 1998. http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/consent-child-and-youth-health-information-practitioners