Abstract

The global HIV policy arena has seen a surge of interest in gender-related dimensions of vulnerability to HIV and violence. UNAIDS and other prominent actors have named gender-based violence a key priority, and there seems to be genuine understanding and commitment to addressing gender inequalities as they impact key populations in the AIDS response. In the quest for evidence-informed interventions, there is usually a strong connection between the research conducted and the policies and programmes that follow. Regarding gender, HIV and violence, is this the case? This discussion paper asks whether the relevant peer-reviewed literature is suitably representative of all affected populations – including heterosexual men, transgender men and women, women who have sex with women, and men who have sex with men – as well as whether the literature sufficiently considers gender norms and dynamics in how research is framed. Conclusions about violence in the context of heterosexual relationships, and with specific attention to heterosexual women, should not be presented as insights about gender-based violence more generally, with little attention to gender dynamics. Research framed by a more comprehensive understanding of what is meant by gender-based violence as it relates to all of the diverse populations affected by HIV would potentially guide policies and programmes more effectively.

Résumé

Les politiques mondiales sur le VIH s’intéressent de plus en plus aux dimensions sexospécifiques de la vulnérabilité au VIH et à la violence. L’ONUSIDA et d’autres acteurs de premier plan ont fait de la violence sexiste une priorité majeure et il semble exister un accord réel et la volonté de s’attaquer aux inégalités de genre qui ont des répercussions sur des populations clés dans la riposte au sida. Dans la quête d’interventions basées sur des données probantes, il existe habituellement une forte relation entre la recherche menée et les politiques et programmes qui s’ensuivent. S’agissant du genre, du VIH et de la violence, est-ce le cas ? Ce document de synthèse se demande si les publications pertinentes avec comité de lecture sont représentatives de toutes les populations touchées, notamment les hommes hétérosexuels, les hommes et femmes transsexuels, les femmes qui ont des rapports sexuels avec d’autres femmes et des hommes qui ont des rapports sexuels avec d’autres hommes. De plus, les publications tiennent-elles suffisamment compte des normes et de la dynamique de genre dans la manière dont la recherche est cadrée ? Les conclusions sur la violence dans le contexte des relations hétérosexuelles, et en ce qui concerne précisément les hétérosexuelles, ne devraient pas être présentées comme des observations sur la violence sexiste dans son ensemble, sans guère prêter attention à la dynamique de genre. La recherche structurée par une compréhension plus complète de ce que recouvre la violence sexiste, comme phénomène qui concerne toutes les populations touchées par le VIH, a le potentiel de guider plus efficacement les politiques et les programmes.

Resumen

La arena mundial de políticas referentes al VIH ha visto un repentino aumento de interés en las dimensiones de género relacionadas con la vulnerabilidad al VIH y la violencia. ONUSIDA y otros actores prominentes han nombrado la violencia de género como una prioridad clave, y parece haber un genuino entendimiento y compromiso para abordar las desigualdades de género, ya que afectan a las poblaciones clave en la respuesta al SIDA. En la búsqueda de intervenciones informadas por evidencia, generalmente existe una gran conexión entre las investigaciones realizadas y las políticas y programas subsiquientes. ¿Es éste el caso con respecto al género, el VIH y la violencia? Este artículo de análisis pregunta si la literatura relevante revisada por pares representa adecuadamente a todas las poblaciones afectadas –incluidos los hombres heterosexuales, hombres y mujeres transgénero, mujeres que tienen relaciones sexuales con otras mujeres, y hombres que tienen relaciones sexuales con otros hombres– así como si la literatura considera lo suficiente la dinámica y normas de género en la manera en que se define la investigación. Las conclusiones sobre la violencia en el contexto de las relaciones heterosexuales, y con atención específica a las mujeres heterosexuales, no deben presentarse como algo que nos permitiría comprender mejor la violencia de género de manera más general, con poca atención a la dinámica de género. La investigación definida por un entendimiento más integral de lo que significa violencia de género con relación a todas las diversas poblaciones afectadas por el VIH posiblemente guiaría las políticas y programas con mayor eficacia.

Gender-based violence as both a cause and consequence of HIV raises significant health and human rights concerns. In recent years, the global HIV policy arena has seen a surge of interest in gender-related dimensions of vulnerability to HIV and violence, resulting in notable policy and programmatic advances with the aim of addressing gender-based violence. Policy directives addressing HIV, gender and violence would seem to call for an evidence base that elucidates how HIV-related violence is mediated by gender roles, norms and dynamics. However, it is not clear that the bulk of empirical research has kept pace with these developments. Within the global policy realm, the concept of gender as a set of norms, as a structurally and institutionally supported system of social relations and as a socially constructed identity, is understood to be distinct from the concept of biological sex. Although the term gender-based violence implicitly recognizes this distinction, the key question is whether researchers are publishing studies that provide insight into how and why gender matters in relation to HIV and violence.

The purpose of this discussion paper is to raise two concerns about the peer-reviewed literature at the intersection of HIV and violence. First, we question whether the literature is suitably representative of all highly affected populations – women and girls; men and boys; men who have sex with men (MSM); and transgender populations. Second, we look at how the concept of gender-based violence as connected to HIV research may get conflated with the concept of violence against women, and how a lack of clarity about the meaning of gender-based violence may undermine the evidence base.

We conducted two literature reviews that inform this discussion: the first, to assess the extent to which researchers studying HIV and violence have focused on the diversity of populations affected by this issue, and the second, to provide some insight into how researchers use the term “gender-based violence”. Both reviews were restricted to peer-reviewed original research articles. For the first review, standard literature review methodologies were used to identify 174 English-language articles that reported on quantitative or qualitative research findings relating to HIV and violence. The articles were located by searching the following databases: EconLit, LegalTrac, LexisNexis, Medline, PAIS International, PolicyFile and Social Science Citation Index. The second review identified recent articles that included the term “gender-based violence” in their titles. A sample of articles was obtained by searching PubMed using the following search string: (“hiv”[MeSH Terms] OR “hiv”[All Fields]) AND gender-based violence[Title]. The search was further narrowed to identify original research published during the years 2008–2013, with the time period chosen to capture the research that is most likely to be informing current policy and programmatic efforts. The abstracts of articles were screened, and articles that did not include a primary focus on HIV were eliminated.

We start with a background section summarising the current state of knowledge with respect to HIV, gender and violence, and move to the discussion of which populations are represented in the literature and how the meaning of “gender-based violence” is communicated. The paper concludes with reflections about key points and recommendations for how research can better inform policy and programmatic work on HIV and violence in the future.

Background

HIV and gender

An estimated 35.3 million people were living with HIV worldwide at the end of 2012, with the number of new infections during that year thought to be 2.3 million.Citation1 The global HIV epidemic poses complex challenges for women, MSM and transgender populations.

Worldwide, 57% of all people living with HIV are women, and HIV is the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age.Citation2 A 2007 systematic review found that MSM in low- and middle-income countries have a 19 times greater risk of being infected with HIV than the general population.Citation3 More recently, UNAIDS reported that MSM globally are estimated to be 13 times more likely to be living with HIV than the general population.Citation1 While national surveillance data are not routinely collected on transgender individuals, studies have also shown a high prevalence of HIV among this population.Citation4–6

Understanding of the linkages between gender and vulnerability to HIV has evolved, and major international institutions now explicitly recognize the ways in which gender norms and gender inequality are drivers of HIV infection.Citation7,8 Concurrently, the global HIV community has become increasingly concerned about the issue of HIV and violence as it affects not only women but also MSM and transgender individuals. All of this is reflected in a proliferation of policy and programmatic initiatives that are intended to be sensitive to gender concerns across the spectrum of HIV prevention, treatment, care and support.

UNAIDS highlights addressing gender inequality as an example of a structural intervention included within combination HIV prevention, alongside behavioural and biomedical approaches.Citation9 Additionally, attention to gender is recommended as part of national and sub-national combination HIV prevention planning efforts and monitoring and evaluation activities. Combination prevention, as articulated by both UNAIDS and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), includes addressing gender-based violence.Citation9,10

It is thus increasingly apparent that addressing gender-related considerations and promoting gender equality are seen as essential for realizing the full benefits of recent advances in HIV treatment and prevention.Citation7 Along these lines, there is programmatic evidence that gender-sensitive and transformative HIV and anti-violence interventions with heterosexually active men are more efficacious than gender-neutral programmes.Citation11–13 Such programmes attempt to modify narrow and constraining aspects of hegemonic male norms in order to reduce HIV risk for both women and men. These programmes also attempt to democratize relationships between women and men, in the direction of more gender equality.Citation14 There is also evidence that HIV prevention programmes that take into account the context of women’s lives, including the structural and relational contexts in which risk is shaped, are more effective than those that only focus on individual-level risk reduction.Citation15

Violence and gender

Violence against women, including emotional, economic, physical, sexual and social violence, constitutes a major global public health and human rights issue.Citation16 The landmark 2005 World Health Organization Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Violence against Women provided irrefutable evidence that violence against women is widespread globally and is a major contributor to the ill-health of women. Data from 15 sites in ten countries revealed that “the proportion of ever-partnered women who had ever experienced physical or sexual violence, or both, by an intimate partner in their lifetime, ranged from 15% to 71%, with most sites falling between 29% and 62%”.Citation16

Despite a vague and often implicit assumption that gender matters in the literature on violence, attention to what this means beyond simply sex-disaggregated data has been limited, with some notable exceptions. As in other areas of public health research, gender is often conflated with sex, or the biology of being female or male.Citation17 Meanwhile, socio-cultural constructs related to how gender shapes risk and behaviour remain much less examined.Citation18

Attention to gender roles and norms in research on violence is critical to enriching our understanding of how to address these social determinants of violence. A small body of recent work has examined how reducing structural-level inequalities between women and men can reduce women’s experiences with gender-based violence. For example, Grabe and Hilliard et al. have found that interventions designed to address violations of women’s property rights and to secure their access to and control over land may lead to less violence against women through pathways directly linked to gendered power relations, including relationship control, household decision-making power, and financial decision-making.Citation19,20 This emergent literature underscores the ways in which gender relations and violence are linked through the intersections between resources, agency, and health outcomes, providing insights that are relevant not only to women but also to men and transgender individuals.

HIV and violence

The earliest peer-reviewed studies reporting on the synergistic pandemics of HIV and violence appear to be from the early 1990s,Citation21–28 although only some of those studies took the relationship between HIV and violence as their primary focus.Citation27,28 In 2000, Maman et al. published a landmark review addressing the linkages between HIV and violence. The authors posited several causal linkages, which continue to offer a useful way to categorize this work. The first entry point recognizes violence as a risk factor for acquiring HIV. Mechanisms for this linkage include: a) violence in the form of forced or coercive sexual intercourse, where condoms are not used, increasing the risk of HIV transmission due to tears and damage to the vaginal and/or anal wall; b) violence, or the threat of violence, limiting a person’s ability to negotiate safer sexual behaviours, thereby increasing the risk of HIV transmission; and/or c) violence experienced in childhood, adolescence or adulthood contributing to risk-taking later in life, thus increasing the risk of acquiring HIV.Citation29 These linkages are most heavily documented in the United States. For example, Machingter et al. carried out a meta-analysis of all US studies focused on violence and trauma rates among HIV-positive women and found that approximately 55% of women who were HIV-positive experienced intimate partner violence, which is twice the national rate of violence against women.Citation30

The second entry point considers individuals already infected with HIV and posits HIV-seropositivity as a risk factor for violence. Individuals who are living (or thought to be living) with HIV may be at an increased risk of experiencing violence as a manifestation of stigma and discrimination, potentially resulting from negative gender norms.Citation29 Some research considering people living with HIV and violence is now beginning to explore other facets of this intersection, such as how violence has an impact on adherence to antiretroviral therapy. For example, Lopez et al. investigated whether there was a correlation between experiencing intimate partner violence and not adhering to medication, using the same methodological approach to assess this issue in women and men. They found that while both women and men reported inter-personal violence, there was a correlation between violence and non-adherence only among women, not men.Citation31 The Machingter team cited aboveCitation30 examined data from a prevention programme with HIV-positive women and transgender women living with HIV and found that those with recent trauma (sexual or physical abuse) had three times the odds of reporting unsafe sex with a partner and four times the odds of non-adherence to their antiretroviral therapy than did those who had not experienced these events.Citation32

Other work engages with the complexity of the interactions between violence and HIV, highlighting, for instance, the principle that violence and HIV are recognized mutual risk factors that together create a vicious cycle for all concerned. Additional factors posited as likely to mediate the relationship between violence and HIV include drug and alcohol use; conflict and emergency situations; and the social, cultural, economic, political and legal climate, e.g. the stigmatisation and criminalisation of certain sexual behaviours and orientations.Citation19,20,33

Increasingly, policy and programmatic efforts focusing on violence and HIV have sought to include interventions that address gender norms and dynamics. These initiatives are particularly concerned with how negative gender norms increase the risk of violence for a range of populations, recognizing that this has implications for HIV prevention, treatment and care. So-called “key populations” addressed by these initiatives include women as a general category (with insufficient attention to who the sexual partners of these women are), MSM and transgender individuals. Of concern, this means the only population not considered “key” is men who engage in heterosexual relationships. Indeed, men engaged in heterosexual relationships have been referred to as “the forgotten group”.Citation34–36

Prominent global actors, including the UN Secretary General, UNAIDS and PEPFAR, have named gender-based violence as a key priority in the response to HIV.Citation37–39 There is widespread recognition of the gender-related dynamics between violence and HIV for key populations, including in regard to the issue of gender identity and behaviour conflicting with gender norms.Citation12,19,34

Over time, several initiatives have produced guidelines on how to integrate violence-related services into relevant HIV programmes and services,Citation10,40 highlighting the gender-related stigma, discrimination and threat of violence that people living with HIV may face from service providers as well as the greater community.Citation41 In addition to the threat of violence because of HIV status, initiatives have focused on violence as an HIV prevention issue, seeking to address the ways in which violence and associated negative gender norms increase vulnerability to HIV infection.Citation10 Indeed, this latter point became the impetus for the development of two randomized trials, the Intervention for Microfinance and Gender Equity in South Africa (IMAGE)Citation42,43 and Shaping the Health of Adolescents in Zimbabwe (SHAZ!).Citation44 These programmes were designed to intervene in the intersecting contexts of poverty, gender inequality and violence shaping women’s HIV risks. Despite some excellent programmatic examples, however, these sorts of interventions have not been taken to scale and are generally not a major feature of the overall response to HIV.

HIV and violence: what does the literature say about who researchers study?

Turning now to the first of the two central issues addressed in this commentary, when researchers first began to consider the role of violence in the HIV epidemic, it appears that violence against women was the predominant concern. This is reflected in the findings of the 2000 review article on linkages between HIV and violence: the vast majority of studies identified by the authors focused on women, while a handful of studies included both women and men as research subjects. Only one study concerned MSM, and none looked at transgender populations.Citation29 Furthermore, few studies considered gender norms or dynamics in relation to the populations studied, and none looked at lesbians (women who have sex with women).

One of the purposes of this commentary is to question whether the evidence base has evolved to reflect all of the populations now recognized programmatically and within policy to need support in relation to HIV and gender-based violence. We sought to address this question by obtaining a snapshot of the English-language peer-reviewed literature on HIV and violence over a span of approximately 12 years: from 2000 (when the Maman et al. review was published) through May 2013. Articles identified in our literature search were initially sorted into four broad categories on the basis of the abstracts: studies of women or girls; studies of men or boys; studies that included both women/girls and men/boys; and studies of transgender women and men. Ninety-nine of the 174 studies focused on women or girls and another 36 included both women and men. Of the 39 studies that focused on men or boys, 21 identified their study population as either gay (5) or MSM (16). None reported on a transgender population.

While a systematic review, including analysis of the full text of articles, would be required to more definitively map what has been published in this realm, the results of our exercise suggest the following points. First, women and girls remain the predominant focus in peer-reviewed literature seeking to provide insight into the linkages between HIV and violence. Second, there is a much smaller body of research on the experience of MSM, even though this population has become a major focus of policy and programmatic initiatives to address HIV and violence worldwide. Strikingly, only 12% of the 174 articles initially reviewed appeared to present evidence about MSM. The vast majority of these studies examine how men who have been sexually assaulted in childhood may later exhibit patterns of sexual risk-taking, including using sex-related drugs and practising serodiscordant, unprotected anal intercourse. Third, published research about HIV and violence affecting transgender populations is scarce, despite concern that transgender populations may be at disproportionate risk for both HIV and violence.

“Gender-based violence”: how do researchers use the term?

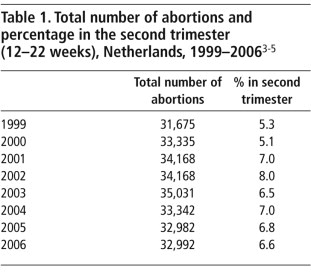

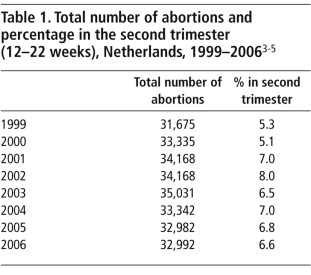

Our strategy for exploring the extent of conceptual clarity in regard to the term “gender-based violence” was to analyse the full text of recent peer-reviewed articles that included the term in the title. This process identified six articles, as summarised in : three from 2013,Citation45–47 two from 2012Citation48,49 and one from 2009.Citation50 All of the articles presented studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries, with one study each from Armenia, Tanzania and Zambia, and three from South Africa.

Table 1 Recent articles (2009–2013) with “gender-based violence” in the title reviewedCitation45Citation46Citation47Citation48Citation49.Citation50

To the extent that these articles are representative of the body of published research on gender-based violence and HIV, our concern about a lack of conceptual clarity seems warranted. Most of these six articles call attention to the needs of heterosexual women as survivors of intimate partner violence or domestic violence, including one that focuses on the role of men as perpetrators.Citation50 While the article titles indicate the researchers’ interest in gender-based violence and not simply violence against women, there is often not a direct explanation of what this concept means, nor of the relevant gender dynamics, within the context of the study presented. Whether an article’s definition of gender-based violence is explicit or – as is more often the case – implicit, the meaning appears to vary across articles.

Thus, conclusions about gender-based violence in the context of heterosexual relationships are often presented as insights about gender-based violence more generally, with little recognition of the experiences of heterosexual men, MSM and transgender women and men. (An exception in this regard is the study by Mboya et al., which includes both women and men in its study of survivors of gender-based violence, albeit without clearly defining who is considered a member of this population.Citation48) There is also typically not an acknowledgment that HIV-associated violence against heterosexual women, while a major issue, is only one component of gender-based violence. Furthermore, the six articles reviewed do not attempt to offer a great deal of insight into either gender norms or gender dynamics – a notable gap and one that may be indicative of the literature more generally, even as attention to both figures prominently in the policy discourse about HIV and gender-based violence.

We submit these observations with the understanding that they are based on what could be called a “convenience sample” of the literature. Published studies relating to HIV and gender-based violence were only identified in our search if they contained “gender-based violence” in the title – a search strategy that was chosen because “gender-based violence” is not a PubMed MeSH term. A large-scale review of multiple databases would need to be conducted to obtain a more comprehensive picture, even as such an undertaking may prove to be logistically challenging if relevant articles are not indexed in ways that enable them to be easily located. In the absence of an exhaustive review of the peer-reviewed literature, our purpose is to raise the question of whether researchers need to give greater attention to explaining what they mean by “gender-based violence” and related concepts.

Conclusions

Our observations about the conceptual underpinnings of research on violence and HIV raise the question of whether the term “gender-based violence” is primarily being used in the HIV field as a synonym for “violence against women”, obfuscating the meaning of gender-based violence and leaving out important populations from this realm of inquiry. It is not essential or even necessarily desirable for all researchers to work on the basis of a common definition of gender-based violence – but if researchers fail to explain how they understand this concept in relation to their central research questions, then making valid comparisons and integrating the findings of individual studies into programmatic and policy efforts will continue to be difficult.

One recommendation suggested by our observations is that researchers should consider HIV, violence and gender across a wider range of locations and populations. A large number of the 174 studies identified in our literature review are from South Africa or the United States. The nature of gender identity and gender relations in these countries may raise particular questions, but they are hardly the only places where gender is likely to matter in relation to both HIV and violence. Further, although some research has been carried out on HIV risk among transgender populations, particularly transgender women,Citation51,52 and also some research showing that transgender populations are at an increased risk of violence,Citation53–55 hardly any work has examined how gender contributes to shaping violence and HIV risk for transgender populations.

The issue of how gender contributes to shaping violence and HIV risk actually needs more careful consideration in relation to all populations. For example, what aspects of the violence that occurs against men who have sex with men are related to gender dynamics, rather than reflecting overt discrimination against a sexual minority? Do transgender men and women experience gender-based violence in different ways relevant to their HIV risk, and is this attributable to different drivers, or are there commonalities? What of heterosexual men – in what ways might the violence that they experience in relation to HIV-status be gender-related? Our findings suggest that researchers who seek to provide greater insight into the relationship between HIV and gender-based violence should be encouraged take into account issues such as these in order to contribute to a more inclusive and informed response.

References

- UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva; 2013. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf

- UNAIDS. Global Fact Sheet: HIV/AIDS. Geneva; 2014. http://www.aids2014.org/webcontent/file/AIDS2014_Global_Factsheet_April_2014.pdf

- S Baral, F Sifakis, F Cleghorn. Elevated risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men in low- and middle-income countries 2000–2006: a systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 4(12): 2007; e339. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040339.

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS action framework: universal access for men who have sex with men and transgender people. Geneva; 2009. http://data.unaids.org/pub/report/2009/jc1720_action_framework_msm_en.pdf

- SD Baral, T Poteat, S Strömdahl. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 13(3): 2013; 214–222. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8.

- S Reisner, J Lloyd, S Baral. Technical report: the global health needs of transgender populations. 2013; USAID: Arlington, VA, USA. http://www.aidstar-two.org/upload/AIDSTAR-Two-Transgender-Technical-Report_FINAL_09-30-13.pdf.

- UNAIDS. Women out loud: how women living with HIV will help the world end AIDS. Geneva; 2012. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2012/20121211_Women_Out_Loud_en.pdf

- United Nations Population Fund [website]. Promoting gender equality: the gender dimensions of the AIDS epidemic. http://www.unfpa.org/gender/aids.htm

- UNAIDS. Combination HIV prevention: tailoring and coordinating biomedical, behavioural and structural strategies to reduce new HIV infections: a UNAIDS discussion paper. Geneva; 2010. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2010/JC2007_Combination_Prevention_paper_en.pdf

- United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Gender-based violence and HIV: a program guide for integrating gender-based violence prevention and response in PEPFAR programmes. Washington, DC; 2011. http://www.aidstar-one.com/sites/default/files/AIDSTAR-One_GBV_Guidance_Sept2012.pdf.

- G Barker. Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India. 2008; Population Council: Washington, DC. http://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/horizons/India_GenderNorms.pdf.

- G Barker, C Ricardo, M Nascimento. Questioning gender norms with men to improve health outcomes: evidence of impact. Global Public Health. 5(5): 2010; 539–553. 10.1080/17441690902942464.

- SL Dworkin, S Treves-Kagan, SA Lippman. Gender-transformative interventions to reduce HIV risks and violence with heterosexually-active men: a review of the global evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 17(9): 2013; 2845–2863. 10.1007/s10461-013-0565-2.

- J Pulerwitz, G Barker. Measuring attitudes towards gender norms in Brazil: development and psychometric evaluation of the GEM scale. Men and Masculinities. 10: 2008; 322–338. 10.1177/1097184X06298778.

- PM Pronyk, JR Hargreaves, JC Kim. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 368(9551): 2006; 1973–1983. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4.

- World Health Organization. WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women: summary report of initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses. Geneva; 2005. http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/summary_report/summary_report_English2.pdf

- N Krieger. Genders, sexes, and health: what are the connections — and why does it matter?. International Journal of Epidemiology. 32(4): 2003; 652–657. 10.1093/ije/dyg156.

- SP Phillips. Including gender in public health research. Public Health Reports. 126(Suppl): 2011; 16–21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3150124/pdf/phr126s30016.pdf.

- S Grabe. Promoting gender equality: The role of ideology, power, and control in the link between land ownership and violence in Nicaragua. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 10: 2010; 146–170. 10.1111/j.1530-2415.2010.01221.x.

- Hilliard S, Bukusi E, Grabe S, et al. Perceived impact of a land and property rights program on violence against women in rural Kenya. Violence Against Women; forthcoming.

- V Brown, L Melchior, C Reback. Mandatory partner notification of HIV test results: psychological and social issues for women. AIDS and Public Policy. 9: 1994; 86–92.

- JB Glaser, J Schachter, S Benes. Sexually transmitted diseases in postpubertal female rape victims. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 164(4): 1991; 726–730. 10.1093/infdis/164.4.726.

- W Handwerker. Gender power differences between parents and high-risk sexual behavior by their children: AIDS/STD risk factors extend to a prior generation. Journal of Women’s Health. 2(3): 1993; 301–316. 10.1089/jwh.1993.2.301.

- WL Heyward, VL Batter, M Malulu. Impact of HIV counseling and testing among child-bearing women in Kinshasa, Zaïre. AIDS. 7(12): 1993; 1633–1637. 10.1097/00002030-199312000-00014.

- C Jenny, TM Hooton, A Bowers. Sexually transmitted diseases in victims of rape. New England Journal of Medicine. 322(11): 1990; 713–716. 10.1056/NEJM199003153221101.

- P Keogh, S Allen, C Almedal. The social impact of HIV infection on women in Kigali, Rwanda: a prospective study. Social Science and Medicine. 38(8): 1994; 1047–1053. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90221-6.

- MA Lodico, RJ DiClemente. The association between childhood sexual abuse and prevalence of HIV-related risk behaviors. Clinical Pediatrics. 33(8): 1994; 498–502. 10.1177/000992289403300810.

- S Zierler, L Feingold, D Laufer. Adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse and subsequent risk of HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health. 81(5): 1991; 572–575. 10.2105/AJPH.81.5.572.

- S Maman, J Campbell, MD Sweat. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 50(4): 2000; 459–478. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00270-1.

- EL Machtinger, TC Wilson, JE Haberer. Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: a meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 16(8): 2012; 2091–2100. 10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4.

- EJ Lopez, DL Jones, OM Villar-Loubet. Violence, coping, and consistent medication adherence in HIV-positive couples. AIDS Education and Prevention. 22(1): 2010; 61–68. 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.61.

- EL Machtinger, JE Haberer, TC Wilson. Recent trauma is associated with antiretroviral failure and HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-positive women and female-identified transgenders. AIDS and Behavior. 16(8): 2012; 2160–2170. 10.1007/s10461-012-0158-5.

- FY Wong, ZJ Huang, JA DiGangi. Gender differences in intimate partner violence on substance abuse, sexual risks, and depression among a sample of South Africans in Cape Town. South Africa. AIDS Education and Prevention. 20(1): 2008; 56–64. 10.1177/0886260510390960.

- SL Dworkin. Men at risk: Masculinity, heterosexuality, and HIV prevention. in press, 2015; NYU Press: New York.

- TM Exner, PS Gardos, DW Seal. HIV sexual risk reduction interventions with heterosexual men: the forgotten group. AIDS and Behavior. 3(4): 1999 Dec1; 347–358. 10.1023/A:1025493503255.

- A Raj, L Bowleg. Heterosexual risk for HIV among black men in the United States: a call to action against a neglected crisis in black communities. American Journal of Men’s Health. 6(3): 2012; 178–181. 10.1177/1557988311416496.

- United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. PEPFAR blueprint: creating an AIDS-free generation. Washington, DC; 2012. http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/201386.pdf

- UNAIDS. Uniting against violence and HIV [website]. 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2014/march/20140312xcsw

- UNAIDS. Getting to zero: 2011–2015 strategy Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Geneva; 2010. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/sub_landing/files/JC2034_UNAIDS_Strategy_en.pdf

- International HIV/AIDS Alliance. Sex work, violence and HIV: a guide for programmes with sex workers. 2008; Hove: United Kingdom. http://www.aidsalliance.org/includes/Publication/Sex_work_violence_and_HIV.pdf.

- G Egremy, M Betron, A Eckman. Identifying violence against most-at-risk populations: a focus on MSM and transgenders: training manual for health providers. 2009; Futures Group: Washington, DC. http://www.healthpolicyinitiative.com/Publications/Documents/1097_1_GBV_MARPs_Workshop_Manual_FINAL_4_27_10_acc.pdf.

- P Pronyk, J Kim, J Hargreaves. Microfinance and HIV prevention: perspectives and emerging lessons from rural South Africa. Small Enterprise Development. 16: 2005; 26–38. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69744-4.

- PM Pronyk, JC Kim, T Abramsky. A combined microfinance and training intervention can reduce HIV risk behaviour in young female participants. AIDS. 22(13): 2008; 1659–1665. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328307a040.

- MS Dunbar, MC Maternowska, M-SJ Kang. Findings from SHAZ!: a feasibility study of a microcredit and life-skills HIV prevention intervention to reduce risk among adolescent female orphans in Zimbabwe. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 38(2): 2010; 147–161. 10.1080/10852351003640849.

- S Gari, JRS Malungo, A Martin-Hilber. HIV testing and tolerance to gender based violence: a cross-sectional study in Zambia. PloS One. 8(8): 2013; e71922. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071922.

- DL Lang, LF Salazar, RJ DiClemente. Gender based violence as a risk factor for HIV-associated risk behaviors among female sex workers in Armenia. AIDS and Behavior. 17(2): 2013; 551–558. 10.1007/s10461-012-0245-7.

- EV Pitpitan, SC Kalichman, LA Eaton. Gender-based violence, alcohol use, and sexual risk among female patrons of drinking venues in Cape Town. South Africa. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 36(3): 2013; 295–304. 10.1007/s10865-012-9423-3.

- B Mboya, F Temu, B Awadhi. Access to HIV prevention services among gender based violence survivors in Tanzania. Pan African Medical Journal. 13(Suppl1): 2012; 5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3589254/pdf/PAMJ-SUPP-13-1-05.pdf.

- EV Pitpitan, SC Kalichman, LA Eaton. Gender-based violence and HIV sexual risk behavior: alcohol use and mental health problems as mediators among women in drinking venues, Cape Town. Social Science and Medicine. 75(8): 2012; 1417–1425. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.020.

- SC Kalichman, LC Simbayi, A Cloete. Integrated gender-based violence and HIV Risk reduction intervention for South African men: results of a quasi-experimental field trial. Prevention Science. 10(3): 2009; 260–269. 10.1007/s11121-009-0129-x.

- JH Herbst, ED Jacobs, TJ Finlayson. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS and Behavior. 12(1): 2008; 1–17. 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3.

- RM Melendez, TA Exner, AA Ehrhardt. Health and health care among male-to-female transgender persons who are HIV positive. American Journal of Public Health. 96(6): 2006; 1034–1037. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042010.

- Heinz A, Melendez R. Intimate partner violence and HIV/STD risk among lesbian, gay, and transgender individuals. Interpersonal Violence 21:193–208. Doi: 10.1177/0886260505282104.

- T Nemoto, D Operario, J Keatley. HIV risk behaviors among male-to-female transgender persons of color in San Francisco. American Journal of Public Health. 94(7): 2004; 1193–1199. 10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1193.

- R Stotzer. Violence against transgender people: a review of United States data. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 14: 2009; 170–179. 10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.006.