Abstract

This article examines, from a human rights perspective, the experience of women, and the practices of health care providers regarding abortion in Chile. Most abortions, as high as 100,000 a year, are obtained surreptitiously and clandestinely, and income and connections play a key role. The illegality of abortion correlates strongly with vulnerability, feelings of guilt and loneliness, fear of prosecution, physical and psychological harm, and social ostracism. Moreover, the absolute legal ban on abortion has a chilling effect on health care providers and endangers women’s lives and health. Although misoprostol use has significantly helped to prevent greater harm and enhance women’s agency, a ban on sales created a black market. Against this backdrop, feminists have taken action in aid of women. For instance, a feminist collective opened a telephone hotline, Linea Aborto Libre (Free Abortion Line), which has been crucial in informing women of the correct and safe use of misoprostol. Chile is at a crossroads. For the first time in 24 years, abortion law reform seems plausible, at least when the woman’s life or health is at risk and in cases of rape and fetal anomalies incompatible with life. The political scenario is unfolding as we write. Congressional approval does not mean automatic enactment of a new law; a constitutional challenge is highly likely and will have to be overcome.

Résumé

Cet article examine, dans une optique des droits de l’homme, l’expérience des femmes et de leur entourage et les pratiques des prestataires de soins de santé par rapport à l’avortement au Chili. La plupart des avortements, jusqu’à 100 000 par an, sont pratiqués subrepticement et dans la clandestinité, les moyens financiers et les relations jouant un rôle clé. L’illégalité de l’avortement va solidement de pair avec la vulnérabilité, les sentiments de culpabilité et de solitude, la crainte de poursuites, les dommages physiques et psychologiques et l’ostracisme social. De plus, l’interdiction juridique absolue de l’avortement paralyse les prestataires de soins de santé et met en danger la vie et la santé des femmes. Bien que l’emploi du misoprostol ait sensiblement aidé à prévenir de plus grandes souffrances et qu’il favorise la capacité d’agir des femmes, une interdiction des ventes a créé un marché noir. Dans ce contexte, les féministes se sont mobilisées pour aider les femmes. Ainsi, un collectif féministe a ouvert une permanence téléphonique – Linea Aborto Libre – qui a été essentielle pour informer les femmes sur l’utilisation correcte et sans risque du misoprostol. Le Chili est à un carrefour. Pour la première fois en 24 ans, la réforme de la loi sur l’avortement semble possible, au moins quand la vie ou la santé de la femme est à risque et dans les cas de viol et d’anomalies fłtales incompatibles avec la vie. Le scénario politique se déroule au moment où nous écrivons. L’approbation par le Congrès ne signifie pas la promulgation automatique d’une loi ; un recours en inconstitutionnalité est hautement probable et devra être surmonté.

Resumen

Este artículo examina, desde el punto de vista de los derechos humanos, la experiencia de las mujeres, las personas a su alrededor y las prácticas de profesionales de la salud relativas al aborto en Chile. La mayoría de los abortos, hasta 100,000 al año, son realizados a escondidas y clandestinamente, y el ingreso y las conexiones desempeñan un papel clave. La ilegalidad del aborto está correlacionada con la vulnerabilidad, sentimientos de culpa y soledad, temor a la interposición de una acción judicial, daños físicos y psicológicos, y ostracismo social. Más aún, la prohibición absoluta del aborto tiene un efecto disuasorio en los prestadores de servicios de salud y pone en peligro la vida y la salud de las mujeres. Aunque el uso de misoprostol ha ayudado significativamente a evitar más daños y mejorar la agencia de las mujeres, la prohibición de ventas creó un mercado negro. En este contexto, las feministas han tomado acción para ayudar a las mujeres. Por ejemplo, un colectivo feminista estableció una línea de atención telefónica, Línea Aborto Libre, que ha sido crucial para informar a las mujeres sobre el uso correcto y seguro de misoprostol. Chile está en una encrucijada. Por primera vez en 24 años, la ley referente al aborto cabe dentro de lo posible, por lo menos cuando la vida o la salud de la mujer corren riesgo, y en casos de violación y anomalías fetales incompatibles con la vida. El escenario político está desarrollándose a medida que redactamos este artículo. La aprobación del congreso no significa la promulgación automática de una nueva ley; una recusación constitucional es muy probable y habrá que superarla.

Chile is one of seven countries that ban abortion under all circumstances.Footnote* This violates women’s human rights, requiring urgent legal review. In March 2014, following a three-year period as Executive Secretary of UN Women, Michelle Bachelet took office for the second time as President of Chile.Footnote† Since the end of 2010, Chileans (especially students) have taken to the streets to demand a range of changes: from a new constitution and the legalisation of same-sex marriage, to natural resource protection and free quality education. The issue of safe and legal abortion became part of the last presidential debate (2013) as all but one of the eight contenders spoke in favour of at least partially liberalising the law.Footnote**

President Bachelet’s new centre-left government decided to address issues such as taxation, educational, and electoral reform. She also appointed prominent feminists to head the Servicio Nacional de la Mujer (National Women’s Service, SERNAM) and tabled legislation granting SERNAM ministerial rank. Her governmental agenda now includes legalising abortion if the woman’s life or health is at risk and in cases of rape and fetal anomalies incompatible with life. Both the head and deputy head of SERNAM have said that this legislation is now a government priority. In her May 21st State of the Nation address in 2014, Bachelet called for an informed and mature debate on abortion, but her agenda constitutes limited reproductive autonomy because it does not go beyond these three grounds. However, she made specific reference to criminalisation with respect to the case of a 17-year-old girl who was charged, while she lay in hospital in a serious condition, with obtaining an illegal abortion.Citation1,2 At the time of writing (October 2014) the government had not introduced its own bill or formally endorsed either of two similar bills awaiting legislative review, tabled in Congress in 2013 by members of the centre-left coalition. There has also been no indication as to whether the proposed legislation will include putting an end to women being reported for obtaining an abortion. Although such initiatives are commendable,Citation3 and would bring the 25-year-old absolute ban on abortion to an end, they do not recognise women’s reproductive rights as human rights. Moreover, any bill that secures Congressional approval is highly likely to face a challenge from the Constitutional Tribunal that must be overcome.Footnote*

This article describes the findings of a comprehensive study of the criminalisation of abortion as a human rights violation in Chile, conducted by the authors in 2013 at the Human Rights Centre, Faculty of Law, Diego Portales University, Santiago, Chile.Citation4

Methodology

Information was obtained on hospitalisations and maternal deaths related to abortion, prosecutions, court cases and cases of people in jail or under the supervision of correctional services due to abortions. The information was collected from official sources, including readily available Ministry of Health statistics and information obtained by special request from the Public Prosecutor, Public Criminal Defender and Department of Corrections Office, whose data are not published in annual reports. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with women who had had illegal abortions, their partners, friends and relatives, to capture their experiences, and with health care providers who assisted them in the process. Members of the feminist collective Linea Aborto Libre who run a hotline providing information on the safe use of misoprostol for abortion, based on World Health Organization (WHO) guidance,Citation5 were also interviewed. The research also included a literature review on clandestine abortion in Chile.

The study was approved by the University Ethics Committee. To protect confidentiality, no names were asked or recorded, and we made a commitment not to reveal identities. Consent forms were marked rather than signed. No audio recordings were made and only written notes were taken due to the risk, albeit unlikely, of a criminal investigation.Footnote† The participants were recruited through an invitation on social networks and using snowball sampling. In order to cover different types of experiences and contexts, people from diverse backgrounds, ages and social classes were contacted. Interviews were carried out from January — July 2013, either face- to-face, or by telephone or Skype with those who were not in Santiago.

The authors interviewed 41 women who had had abortions, 12 partners, friends or relatives of some of these women, and 8 health care providers. Two of the women had been prosecuted for illegal abortions.Footnote** One was sentenced; the criminal proceedings against the other were suspended. It was not possible to reach the original number of 100 women participants as planned. As abortion is a crime and normally silenced, the reluctance of women to speak about their stories became evident; however, those who did share their testimony for this research expressed relief afterwards. Due to the limitations of carrying out a study of a criminalised practice, it is difficult to describe the findings as reflective of all experiences and practices of abortion in Chile. Nonetheless, the results are corroborated by the literature on abortion in an illegal context.

Historical context of the law on abortion

Chile is one of the few countries that does not permit abortion under any circumstances. The 1931 Health Code regulated therapeutic abortion until it was repealed in September 1989, a few months before the end of the regime of dictator Augusto Pinochet in March 1990.Citation6 The law had permitted the termination of pregnancy to save the woman’s life or health and required the signed approval of two doctors. It was interpreted restrictively. Only in the years under socialist President Salvador Allende (1970–1973) did a group of physicians in one of Santiago’s hospitals broaden the interpretation of the law to include abortions up to the 12th week of pregnancy.Citation7 Since 1989, the Criminal Code on abortion has not been reformed, despite it being 24 years since Chile returned to democracy, and in spite of efforts by feminists and women’s movements.

Prevalence and criminalisation

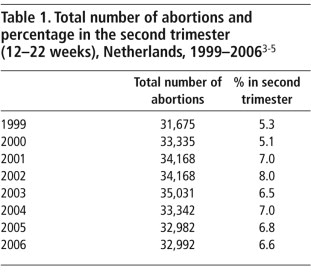

Chilean Ministry of Health data show that in 2008, over 33,000 women were hospitalised due to abortion complications.Citation8 A review by Molina et al. of 10-year hospital discharge data on abortion found that 10% involved ectopic pregnancies, 40% fetal abnormalities, and 34.7% registered as unspecified or unknown reasons for the complications.Citation9 The study concludes that the “unspecified” reasons could be attributable to induced abortions.Citation9 Although several estimates exist,Citation6,10 the actual number of induced abortions is unknown. Based on a 1.94 global fertility rate, 64% contraceptive use and over 33,000 hospitalisations, a prominent epidemiologist recently estimated the annual number of abortions as 60,000 – 70,000.Footnote* Others have estimated over 100,000.Citation9

Despite the high prevalence of illegally induced abortions, the ratio of numbers of abortions to prosecutions is very low. However, the Office of the Public Prosecutor reported to the authors as many as 310 cases that were investigated and tried in the period between January 2011 and September 2012, a far higher number than anywhere else in the world.Citation11Footnote† The number of people actually involved is uncertain because the statistics only register the number of criminal offences, not the number of people involved. For instance, as a defence attorney, first author Casas has observed that up to six people have been investigated in a single case: e.g. one where five women were charged with obtaining an abortion and one physician for performing them. Moreover, the Public Criminal Defender’s Office (Public Defender) only reports on the number of clients they have represented. In the same period as above, they defended 140 men and women. In addition, however, many people hire private attorneys; an unpublished report by the Public Defender revealed that 11% of women who initially preferred a public defender later hired a private lawyer.Citation12 Most women who were prosecuted had children and were poor, reflecting the fact that those who receive public legal services tend to be poor, as a previous study on abortion criminalisation found.Citation13 The majority had used misoprostol.

The Public Defender acknowledged in a newspaper article that the law has an unequal effect on women, especially the poor.Citation14 He remarked on the cases of two adolescent girls whose experiences exemplify how medical confidentiality may be violated. They had been raped, yet they were found guilty of illegal abortion and stigmatised twice by the criminal justice system, instead of being protected as victims of sexual violence.Citation14

Abortion practices in a context of illegality

While the ratio of hospitalisation to prosecution suggests that the law is completely ineffective for sanctioning abortion, it succeeds, nevertheless, in filling women with fear and stripping them of their right to decide about their own bodies. Although the law fails in its aims to prevent abortion, it has a strong symbolic power which signals to women that they cannot escape an unwanted pregnancy without consequences. A vast majority of the interviewees believed that abortion should be a right, provided and guaranteed by the State. In their testimony, they said that the very experience of operating in secrecy generated the worst (subjective) fears and (objective) risks.

In Chile, as elsewhere, banning abortion does not do away with the practice but simply drives it underground. It forces women to seek clandestine abortions whose safety varies depending on price and social and personal networks. In Chile, the rate of deaths from unsafe abortion is very low, especially compared to other countries where it is legally restricted.Citation9 Because of this, despite the illegal context, some have argued that the prohibition of abortion does not have an impact on mortality or morbidity.Citation15 However, according to the Guttmacher Institute:

“a body of research, largely published in peer-reviewed journals, makes clear that the decline in maternal morbidity and mortality from unsafe abortion in Chile in the past decades coincides with greater access to and use of contraceptives, as well as the use of less dangerous clandestine abortion methods… [in particular] the use of misoprostol as an abortifacient, which is associated with a lower risk of severe health consequences than the use of illegal surgical procedures, and is considered an important explanatory factor in the decline in abortion-related deaths in the past two decades.”Citation16

The practice of abortion has changed in Chile due to the use of misoprostol and vacuum aspiration used by trained health providers. Dilation and curettage (D&C) seems to be less common than in the past, another reason for the decrease in abortion-related deaths in Chile. Nonetheless, there are still some women who use high risk methods, such as scissors, as reported by the Public Defender and others.Citation9,14,17

The methods our interviewees used ranged from safe to unsafe methods and practices. Those who had abortions with trained physicians reported widely differing conditions and prices, ranging from several thousand dollars for a safe procedure to two hundred dollars for a less safe one. One woman travelled to neighbouring Peru and returned with complications, after the physician had used D&C. For many women, the situation was dire. Five spoke about undergoing curettage or vacuum aspiration without anaesthesia. If they cried or fainted, they were chided. The issue is addressed with market logic: the abortion ban fuels demand and doctors and midwives move in, charging hefty sums for abortions that may or may not be safe, even up to five thousand dollars. One of the doctors interviewed reported that price is based on weeks of pregnancy and as the weeks rise so does the price.

Most women are asked to pay cash.Footnote* One health care provider who advises women on the use of misoprostol said that three of his patients had been asked for sex before they had found him. Another woman told of how, while she was undergoing the procedure, her boyfriend was asked for more money because the doctor realised that she was the daughter of an important public figure. Because abortion is forbidden, it is not possible to report any such wrongdoing by practitioners. Thus, illegality makes for good business in more than one sense, as has been documented in Poland.Citation18

In the matter of safe abortion, many women lack access to information and many more cannot afford the cost. Studies conducted in Chile and, for example, El Salvador show that disadvantaged women and girls who cannot afford safe abortions account for most instances of complications, exposing the appalling social inequity. Reports from the Public Defender, El Salvador and others show that poor women who depend on public health facilities and services for emergency care with complications are also more likely to be prosecuted.Citation11,13,17,19,20

The use of misoprostol in the past 15 years has changed the scenario drastically, however.Citation21 In Chile, misoprostol is also commonly used to induce labour and facilitate IUD insertion.Citation22 Several pharmaceutical companies have consistently been refused permission to manufacture or sell misoprostol for gynaecological use.Footnote† Medical experts have recognised that medical abortion has decreased the risks associated with rubber probes, douching and other harmful methods, such as scissors and wires, and that constraining misoprostol availability may have more adverse consequences.Citation9

To stem misoprostol use, the Chilean authorities also restricted sales to health care facilities in 2001.Citation23 A black market involving imported supplies soon materialised. It is difficult to ascertain how purchasers get the drug; it could come from neighbouring countries as much as from stealing the drug from the formal market chain between pharmaceutical companies and institutional health facilities.

According to our interviewees misoprostol can be obtained on the black market for prices ranging from US $70—215, but as it is an under-the-table transaction, product quality is far from assured. The sellers are normally searched for online or through a friend or acquaintance who previously bought the pills or knows a seller. The media report that women usually meet with sellers at subway stations in Santiago.Citation24 Two interviewees obtained the pill from foreign feminist organisations, which sent the pills by post.

Misoprostol efficacy varies depending on the quantity used and also the number of weeks of pregnancy, which also affects safety. Those who sell the drug usually know the associated risks, but an illegal, unregulated market implies wrong information and unavoidable misunderstandings. One of the women interviewed, who was sold counterfeit pills, had to wait for four weeks to secure a new supply, and only found a second supplier when she was around 15 weeks pregnant. This supplier asked for an ultrasound proving the number of weeks, then he recommended a higher dosage because she was more than 12 weeks pregnant, believing that more drugs were required, but this is not the case. He also advised her to go to a doctor for post-abortion care. The woman followed these instructions. When she took the pills she was on her own; she passed out after four hours of excruciating contractions and finally aborted. When she eventually saw a doctor she was told that the dose could have killed her. Another woman, a nurse, recognised the counterfeit pills that the supplier was attempting to sell her and recalled the lack of clear information about the required dosage. She eventually managed to obtain a supply from a midwife and safely aborted with misoprostol.

Misoprostol use seems to be directly related to socio-economic status and access to information. Younger women and those with internet access were more likely to find and obtain it. This was less likely among older women with less access to the internet and therefore less access to information, and for those who live in rural areas. The woman who went to Peru did not have a computer to search for information on the web. Aside from the obvious importance of money, social networks and access to online sources, the search can be very confusing and contradictory, with some interviewees admitting they would not have known where to turn or how to decide had they not received assistance from women who had already done so. For instance, one respondent spoke of going online to find, in addition to misoprostol, a bewildering array of options ranging from “Eastern massages” to medicinal herbs.

Respondents were expressly queried on their feelings regarding self-induced abortion. Some perceived not needing a doctor as a relief and as a reclaiming of their own bodies, which touches on key issues of agency. However, lack of medical knowledge can be a frightening experience. First-time users do not know what to expect. Some women felt they were completely on their own, for better or for worse. Others chose this option in order to avoid exposing others to criminal prosecution.

Women familiar with abortion options can often choose based on their own or others’ experience but even so, basic safety requirements may nevertheless not always be met. Misoprostol use may enhance agency for some; for others, medical care is still closely related to being cared for, especially for those dependent on public health services.

“As I could not tell the doctor the truth, because I didn’t want to end up in jail, I had to put up with a much riskier option… Also, not having money, I was really angry thinking about this friend who could afford proper care… Being forced to go to a slaughterhouse because you’re poor is a violent experience.” (Interviewee)

A participant who had an abortion five years prior to the interview now volunteers to help and support other women. Some respondents noted that feminist groups who provide online information and sourcing of the pills have helped increase the frequency of misoprostol use as a do-it-yourself option without the assistance of a third party. Five respondents were feminists or progressive health care workers with experience in misoprostol use. None of them charged for their support, and in fact three actually bought the drug for others who lacked access or money, although most of the women whom they assist obtain the drug on their own. One interviewee who had reportedly assisted 87 women over the years recalled providing post-abortion support to a woman who, in spite of her strong wish to be a mother, chose abortion to preclude being tied to a former partner for life.

Linea Aborto Libre: the thin line between legal and illegal

In 2009, the Lesbians and Feminists for Freedom of Information CollectiveFootnote* launched a free hotline providing information on misoprostol-based abortion. In December 2012, they published an information handbook. The Collective is a solidarity network designed to counteract the effects of the ban and provide abortion support; they have no political affiliation beyond feminist activism and do not lobby for legislative reform because they reject any dialogue with the State or government representatives.

The hotline operates daily from 8 pm–11 pm with volunteers taking turns to field calls, estimated by the Collective at some 20,000 between May 2009 and May 2013. Using a strict protocol, designed to keep the hotline within the confines of the law, information is provided only to persons of legal age and is based on World Health Organization guidance, which is readily available on the WHO website. While no information on obtaining the pills is provided, a volunteer noted that determining a safe source was a common question, with many callers expressing concern about product quality and possible scams. Unsurprisingly, several women interviewed claimed that black market misoprostol sales are controlled by racketeer-style sellers.

The Collective also leads workshops providing practical information on abortion and the legal framework. From May 2012 to May 2013 they held 32 such events for 820 women and men in the cities of Santiago, Valparaíso, Antofagasta, Iquique, Concepción and Temuco. The Collective is working on the establishment of a Centro de Atención en Salud Sexual y Aborto Seguro (Centre for Sexual Health and Safe Abortion Assistance) in Santiago that will be in operation by the end of 2014. The Centre will include a range of health care specialists and women volunteers to provide a safe and supportive space.

The interviewees reported to the authors that three of their fellow Collective volunteers have faced criminal inquiries. They were not aware of all the details of these investigations, but they knew that none had led to prosecution. One originated in a complaint laid by a Protestant cleric, another was initiated by a zealous prosecutor and the third was launched by a prominent litigant in an emergency contraception case. The first two inquiries were stayed and the third was shelved after police questioned two volunteers. Indeed, as the Collective only provides publicly available information, its work is completely above legal reproach.Citation4 A fourth complaint has been laid over a misoprostol workshop held at a university campus in September 2013, but prosecutors have yet to act on it.

The Collective’s work, based on the right to information, resembles that of Open Door and the Well Woman Centre in Dublin, two Irish non-profit organisations prohibited by the Irish High Court and Supreme Court from providing pregnant women with information on abortion facilities outside Ireland.Citation25 In 1992, on appeal, the European Court of Human Rights found that these restrictions constituted unjustified interference with the right to impart or receive information, in violation of article 10 of the Convention on the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. The Court reasoned that if women were able to obtain the same information through other channels, any restrictions on information would not necessarily prevent them from going to Great Britain for an abortion, and may cause greater harms to women than intended.Citation25

The chilling effect of the law

In Chile, conservative rhetoric holds that protecting a woman’s life and health requires no legal reform. The argument is based on the double-effect theory, which allows practitioners to provide treatment or perform a procedure that may result in an unintended abortion if a woman’s life or health is at risk.Citation6,26 In January 2014, Chile’s delegation under conservative President Piñera’s administration argued exactly this point at the Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review. Then, in May 2014, after Bachelet’s presidential announcement of support for a bill on abortion, it was put forward also by the Chancellor, a gynaecologist, of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.Citation27

But even if this theory were true, interviews with health care providers reveal that the law, as it stands, often leads to precious time being wasted waiting for the condition of the woman and/or embryo/fetus to improve or deteriorate before doing an abortion to save the woman’s life. As a physician told the authors, ambivalence and wasted time led in his hospital to the otherwise preventable death of a teenager who was carrying an anencephalic fetus, or as was documented in 2003 the case of a woman with a molar pregnancy with a fetus with severe chromosomal abnormality.Citation28 The woman had requested termination of the pregnancy, but the hospital staff and the Minister of Health at the time responded that nothing could be done because of the law. However, when her health deteriorated and she went into emergency care, the medical team took it upon themselves to end the pregnancy.Citation28 These cases resemble that of Savita Halappanavar, who died in Ireland in 2012 because she was denied the timely termination of a 17-week pregnancy, which had miscarried, and others in other countries.Citation26

At least in the realm of public health, provider fear of running foul of the law is more acute in cases of serious fetal malformation incompatible with life. While most practitioners share the common-sense conclusion that continuing a pregnancy involving a fetus with no chances of survival is an exercise in futility, most feel that the law takes away their latitude to terminate the pregnancy at an early stage.

Some practitioners among those interviewed have helped or know of others who have helped rush a birth at the 22nd week of pregnancy or more in order to avoid prolonging a woman’s pain and sorrow. As one midwife said, it is inhumane to prepare women for the birth of a malformed baby while withholding counselling from those carrying a nonviable fetus. In the 1990s, one interviewee, mother to three children, whose husband was dying from cancer, became pregnant. The fetus was not viable. She was suffering from severe bleeding and her life was compromised. When the symptoms began, she was told they had to wait until she reached 24 weeks because there was no other option. When she was 22 weeks pregnant she was hospitalised, told she was dying and asked by a doctor if she would consent to an abortion were the therapeutic abortion law in place. She responded affirmatively. Later a midwife examined her and then her waters broke. She believes they did something to break her waters.

Patient confidentiality and prosecution

Chilean law has contradictory patient confidentiality provisions. Health care providers are required to report apparent abortions, according to the Criminal Procedure Code, but the same Code exempts them from having to disclose details in court.Footnote* So, for instance, a health practitioner who reports a suspected abortion and is then summoned to testify could choose to withhold the information. Moreover, it is a criminal offence under the Criminal Code to divulge confidential information obtained in the doctor–patient relationship. During the first Bachelet administration, the Ministry of Health attempted to deal with this issue by enacting a directive requiring health care providers to uphold patient confidentiality.Citation29 However, the directive does not have the force of law, as argued in May 2014 by a prosecutor when the Health Minister publicly decried the prosecution of a young woman turned in to the police by a public hospital.Citation30 It is not possible to assess the effect of the directive. Since 2009 women are still being reported to the authorities by hospitals,Citation2 and gathering from the information given by the majority of the health care providers interviewed and the experience of first author Casas in teaching and training midwives, the directive is not widely known.

During the interviews, one of the most recurrent words was fear. Fear of dying, of not waking up from sedation, of complications, of not being able to get pregnant again, or of ending up in the hospital. But, the greatest of all was the fear of prosecution. We interviewed two women who were prosecuted. One was found guilty; the procedure against the other was suspended but the provider was found guilty. Both women were identified by the police through a media story on clandestine abortion.Footnote* Neither of them spent time in prison, but the one who was found guilty was released on bail throughout the investigation and trial.Footnote† The other woman never went on trial as the defence and prosecution agreed on a conditional suspension of the criminal charges. Another interviewee told of a very close call that happened to her more than 20 years ago. She loaned abortion money to a woman who was prosecuted and sentenced along with the doctor who performed the procedure. Had the woman revealed the source of the money, she too would have been prosecuted. Alarmingly, both women spoke of being ill-treated by their counsel.

In a recent study, the Public Defender found that most of their illegal abortion clients were reported to the police while in hospital.Citation12 Studies conducted over a decade and a half ago had similar findings.Citation13,17

Eight of our 41 women interviewees had abortion complications, including six who had recently received emergency care. Two main issues emerge when women seek treatment for abortion-related complications: whether or not medical confidentiality is upheld and whether or not humane care is provided. One woman felt so mistreated at a public hospital that she almost walked out, to go to a private clinic. She believed that the attending nurses and midwives realised she had had an induced abortion. Another woman recalled being interrogated by the health care staff about misoprostol use while under sedation following curettage, but she was sufficiently alert and denied having used misoprostol. A male midwife said that mandatory reporting taints the doctor—patient relationship. He recalled one case where the health care staff obsessed over extracting information from a patient, to the point of neglecting her care. He vividly recalled the patient’s look of horror while being interrogated and the dismay of her relatives when told of her abortion.

If complications arise and there is evidence of an induced abortion, the word “hush” takes on a whole new meaning in emergency rooms. One respondent who had gone to emergency care referred to long pauses and silences whenever the health care providers posed questions about the pregnancy and the “miscarriage”.

One physician interviewed explained that a life-threatening condition, or abortions too obvious to ignore, leave doctors no option but to report. Thus, it seems doctors’ behaviour is motivated more by fear of administrative consequences than concern for patient protection and care. From their point of view, this may be justified. The authors are aware of only a single case in which the Ministry of Health intervened and invoked the medical obligation to safeguard confidentiality in a doctor’s defence, after an administrative inquiry was opened against him. In this case, all administrative charges were withdrawn and the doctor was not penalized. This does not seem to have become a precedent, however.

As was discussed with the first author in a meeting in May 2014 at the Ministry of Health, doctors who treated a young woman suffering from severe blood loss reported her because she kept shouting that she had used misoprostol. As our findings indicate, it is probable that the woman gave the information because she was afraid for her health. Some women want to tell the truth in order to get appropriate medical care; others refrain from doing so in order to avoid criminal prosecution.

Current legislative debate

In 2012, three bills to permit abortion for three indications were discussed in the Senate: for the protection of the life or health of the woman, in case of serious fetal abnormalities incompatible with life, and when the pregnancy is the result of rape.Citation31–33 The three bills were all voted down, but they were relevant for opening the discussion in the Parliament and also in the public arena.

Since then, three new bills have been tabled, which are awaiting discussion, either in the Chamber of DeputiesCitation34,35 or the Senate.Citation36 Two of them propose to decriminalise abortion to protect the woman’s life or health, in case of rape and serious fetal malformationCitation35–37 in the same terms as the 2012 bills. One proposal was initiated by the Movimiento para la interrupción legal del embarazo (Movement for legal abortion, MILES), a network of organisations and individuals, which presented the text to lawmakers willing to take forward legal reform. Then another bill proposing to legalise abortion on the woman’s request during the first trimester of pregnancy was tabled in August 2014.Citation37

The reform of the Criminal Code is promoting further discussion on abortion law reform. In 2013, former President Piñera convened an expert commission to review and propose a revision of all criminal legislation. In their preliminary work, the Criminal Law Scholars’ Commission, in a 4-to-3 majority vote, proposed to legalise abortion on woman’s request in the first trimester and permit abortion in the second trimester on grounds of risk to health or life (Personal communication, Héctor Hernández, Professor of Criminal Law, Universidad Diego Portales Law School and member of the Commission, September 2014). Piñera’s government did not accept the experts’ recommendations and instead tabled its own proposed new Code in January 2014. Bachelet’s Minister of Justice, in April 2014, called a halt to the legislative debate on this draft Code and convened some members of the expert group to discuss and review the draft Code in light of their own recommendations (Personal communication, Hernández, ibid). Hence, the possibility of abortion law reform, which began in a different political scenario, now has many more opportunities than in the past. At this writing, the work on this Commission has not been finalised, and it is unknown whether the government will present its own bill or support one of the bills that has already been tabled.

Bachelet declared in May 2014 that the abortion debate and regulation was urgent but parliamentary discussion has been postponed to the end of 2014, generating scepticism and concern among feminists that once again abortion law reform is not getting the political priority it deserves.

The National Women’s Service will lead the reform from the Executive, changing what has been a traditional role for the Ministry of Health.Citation38 This is an important political signal — if it means that women’s reproductive autonomy will be the focus of the discussion. Although the public health implications are very important, women’s agency is the crux of the issue.

In this light, the language used in the public debate should also change. All political actors should call the bills by their names, for example, legalisation of abortion on grounds of life, health and rape, rather than using the term “therapeutic abortion”, as this term gives too much power to medical staff, leaving the decision whether to terminate the pregnancy to the discretion of health practitioners. Except for the short period of time under Allende in Chilean history, the application of this exception was very restrictive.Citation7 Changing the focus will assign to women the central role, having full information to decide freely whether to continue a pregnancy or not, with mechanisms to ensure that information will be complete and accurate, given the paternalistic behaviour of the medical profession.

None of the current abortion law reform bills in Chile contain provisions for strengthening patient confidentiality or how to proceed in a case of rape. The expert Commission’s recommendations present a comprehensive proposal, following German law, which includes, among other things, provision both for conscientious objection and penalties for health care providers who undermine women’s rights through their practices and omissions (Personal communication, Hernández, ibid). Imposing penalties on providers addresses the emerging opposition and signals their responsibility. The Chancellor of the Catholic University declared that if law reform were enacted, the Catholic University Hospital would refuse to do abortions, exercising conscientious objection. Aside from his error in arguing that institutions have a right to freedom of conscience,Citation27 when only individual people have such a right, his statement demonstrates the challenges that any reform will face.

Chile is at a crossroads, the discussion might lead to a law that permits some abortions, with limitations, but new obstacles might ensue at the Constitutional Tribunal, which make victory an uncertainty. Given the highly political nature of appointments to the Constitutional Court and its previous record of declaring emergency contraception unconstitutional,Citation3 it is not possible to predict the outcome.

Conclusions

Criminalisation of abortion violates a range of women’s human rights, including the right to equality, to life and to physical and mental integrity, to be free from cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment, to privacy, and to due process. When abortion is illegal and clandestine, most of the harm becomes invisible and the consequences unknown, yet Chilean law allows abortion to remain hidden and has taken no steps to prevent this since 1989.

Today, Chile has the opportunity to legislate. Abortion should be legalised on the woman’s request, at least in the first trimester, and throughout pregnancy to protect the life and health of the woman, in case of serious fetal anomalies, and when the pregnancy is the result of rape. Even though the more limited indications do not fully guarantee reproductive autonomy, they are at least a first step towards it.

Poster announcing a demonstration to open the debate on abortion, and against the violence towards women who have been raped and forced to become mothers and in support of the right to decide and free, legal abortion, Santiago, Chile, 11 November 2014.

The abortion law should place the rights and needs of women first. One of the aspects that the law should include is medical confidentiality. Incriminating women based on privileged information known to medical practitioners negates due process. If the law were not to be amended in this respect, health care providers who report women should be required to inform patients of their rights, including the right to remain silent, so they understand that information so obtained could be used against them. Medical staff and health professionals should be trained about their obligations regarding women’s human rights. In particular, patient confidentiality must be guaranteed according to the Directive and international human rights standards.

President Bachelet has shown the political will to transform this scenario. Although her proposed reforms remain limited, they should go some way toward protecting women from grievous harm. Talking about abortion, which was silenced for many years, is finally part of the public debate. Feminist groups have been crucial not just in putting abortion on the agenda, but also in generating support networks to ensure abortion takes place under less dangerous conditions. However, right-wing politicians and religious authorities are demanding that Bachelet upholds the current law. As a former Executive Secretary of UN Women, she should be expected to push for political change, in spite of adverse reaction within some ranks of her government. If she does not, she risks losing the moral authority that she gained, as Dilma Rousseff has done in Brazil, as a spokeswoman for women’s rights.

Notes

* In Latin American and the Caribbean, the other countries are: El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras and Dominican Republic.

† Bachelet’s first presidency was March 2006 — March 2010.

** A bill, tabled by then Senator Evelyn Matthei (member of the right wing party Independent Democrat Union) and Senator Fulvio Rossi (member of the Socialist Party of Chile), allowed abortion in case of serious fetal anomalies or risk to the woman’s life or health. It was voted down in the Senate in April 2012. Matthei later ran for president against Bachelet.

** The Chilean Constitution has a clause that states the law will protect the “unborn”, which has been interpreted by most constitutional scholars as a prohibition on abortion. With this interpretation, in 2008 the Constitutional Tribunal declared the section on emergency contraception in the Fertility Regulation Guidelines “unconstitutional” as a possible abortifacient, following a challenge by a group of conservative Deputies.

† Although both authors are lawyers, we were not protected by attorney-client privilege.

** First author Casas met them in 2009. One woman approached her after being found guilty and needing help to obtain authorisation to leave the country because she had won a scholarship, and her verdict did not allow her to leave Chile for 1.5 years. The other was charged in a case in which Casas was the defence attorney for another woman.

* Soledad Díaz, Slide presentation Aspectos médicos del aborto, Instituto Chileno de Medicina Reproductiva, in which data prepared by Olav Meirik was provided, Santiago, 2012.

† In most countries with highly restrictive laws, there are far fewer such prosecutions.Citation11

* One woman paid with a cheque, which enabled the police to incriminate the health care provider.

† In 2000, the Ministry of Health issued a technical warning instruction (Ordinario N° 2A/5239, 31 August 2000). The Chilean Public Health Institute (ISP) turned down an application for the manufacture and sale of misoprostol pills for gynaecological use in 2008 and made specific reference to the earlier warning. The ISP again denied permission in 2010 and 2012. In June 2014, a committee reviewed a new application; the public records indicate a decision is pending. The minutes reveal a suggestion to leave the decision pending in similar terms to the ones that preceded previous rejections. See: http://www.ispch.cl/sites/default/files/documento/2012/08/CE11%20191208.pdf and http://www.ispch.cl/sites/default/files/documento/2012/08/CE6%20300710.pdf.

* Linea Aborto Libre (Free Abortion Hotline): www.infoabortochile.org.

* Article 175 (d) of the Criminal Procedure Code requires a report, while articles 246 and 247 of the Criminal Code and article 303 of the Criminal Procedure Code exempt disclosure of privileged information.

* Other women were also investigated and prosecuted because of the media report. All providers were found guilty and sentenced to jail. In addition to the interviewee who was found guilty, another woman, who had an abortion at the same time and with the same provider, was also found guilty.

† She was prosecuted before the new criminal justice system came into effect in Santiago in 2005. The old system involved an inquisitorial investigation in which the same judge led the investigation, laid charges and adjudicated.

References

- M Bachelet. Mensaje Presidencial 21 de mayo 2014. http://21demayo.gob.cl

- C Cortés. Sename lamenta caso de joven que abortó en su casa con misotrol y reconoce que es ’algo que ocurre’. 14 mayo. 2014; La Tercera.

- F Muñoz. Morning-after decision: legal mobilization against emergency contraception in Chile. Michigan Journal of Gender and Law. 21(1): 2014; 123–175. http://repository.law.umich.edu/mjgl/vol21/iss1/3.

- L Casas, L Vivaldi. La criminalización del aborto como una violación a los derechos humanos de las mujeres. Informe Anual sobre Derechos Humanos en Chile. 2013; Universidad Diego Portales: Santiago, 69–120.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2nd ed, 2012; WHO: Geneva.

- B Shepard, L Casas. Abortion policies and practices in Chile: ambiguities and dilemmas. Reproductive Health Matters. 30(15): 2007; 202–210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30328-5.

- JE Pieper Mooney. The Politics of Motherhood. Maternity and Women’s Rights in Twentieth Century Chile. 2009; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh.

- Ministerio de Salud. Orientaciones técnicas para la atención integral de mujeres que presentan un aborto y otras pérdidas reproductivas. 2011; Ministerio de Salud: Santiago.

- R Molina-Cartes, T Molina, X Carrasco. Profile of abortion in Chile, with extremely restrictive law. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 3: 2013; 732–738. 10.4236/ojog.2013.310135.

- G Maira, P Santana, S Molina. Violencia sexual y aborto. Conexiones necesarias. 2008; Red Chilena contra la Violencia Doméstica y Sexual: Santiago.

- International Campaign for Women’s Right to Safe Abortion. Abortion in the criminal law: exposing the role of health professionals, the police, the courts and imprisonment internationally. October 2013. www.safeabortionwomensright.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Abortion-in-the-criminal-law-16-Oct-2013.pdf

- Defensoría Penal Pública. Delitos de aborto e infanticidio: delitos procesados en Chile. 2009.

- L Casas. Women prosecuted and imprisoned for abortion in Chile. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 29–36. 10.1016/S0968-8080(97)90003-3.

- Toro I, Basadre P. Cómo opera la justicia en los casos de aborto: la historia de tres condenadas por el “delito de mujeres pobres”. The Clinic. 12 June 2014.

- E Koch, J Thorp, M Bravo. Women’s education level, maternal health facilities, abortion legislation and maternal deaths: a natural experiment in Chile from 1957 to 2007. PloS One. 7(5): 2012; 10.1371/journal.pone.0036613.

- Review of a Study by Koch et al. on the Impact of Abortion Restrictions on Maternal Mortality in Chile. Guttmacher Advisory. Guttmacher Institute, 23 May 2012. https://www.guttmacher.org/media/evidencecheck/2012/05/23/Guttmacher-Advisory.2012.05.23.pdf.

- L Casas, R Cordero, O Espinoza. Defensa de mujeres en el nuevo sistema procesal penal. 2009; Defensoría Penal Pública: Santiago.

- A Chelstowska. Stigmatisation and commercialisation of abortion services in Poland: turning sin into gold. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(37): 2011; 98–106. 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37548-9.

- Aguirre M, Romero de Urbiztondo A, Mata VH, et al. Del hospital a la cárcel. Consecuencias para las mujeres por la penalización sin excepciones, de la interrupción del embarazo en El Salvador. San Salvador: Agrupación Ciudadana para Despenalización del Aborto Terapéutico, ético y eugenésico, 2012. http://agrupacionciudadana.org/phocadownload/investigaciones/mujeres%20procesadas%20011013.pdf. An excerpted version of this paper in English is available in this journal issue: From hospital to jail: the impact of El Salvador’s total criminalization of abortion on women. Reproductive Health Matters 2014;22(44):52–60. Doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)44797-9.

- Centre for Reproductive Law & Policy, Open Forum on Reproductive Health and Rights. Women behind bars. Chile’s abortion laws: a human rights analysis. New York; 1998.

- Rojas C. El día después del aborto. El Dínamo. 2 Agosto 2013.

- Federación Latinoamericana de Sociedades de Obstetricia y Ginecología. Uso del misoprostol en obstetricia y ginecología. 2013. http://www.flasog.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Uso-de-misoprostol-en-obstetricia-y-ginecolog%C3%ADa-FLASOG-2013.pdf

- M González. Abortos on line. Venta de misotrol en Internet. Revista Nos. 2007. c-y-proyecto-de-aborto-hay-que-poner-sobre-la-mesa-los-derechos-del-que-esta-por-nacer.html

- Fernández O. El mercado negro de los fármacos abortivos. laterceracom. 2014.

- Open Door and Dublin Well Woman v. Ireland. European Court of Human Rights; 1992. Pars. 66–77.

- M Berer. Termination of pregnancy as emergency obstetric care: the interpretation of Catholic health policy and the consequences for pregnant women. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(41): 2013; 9–17. 10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41711-1.

- Emol.com, Rector de la UC: Aunque la ley lo mande “no vamos a aplicar” abortos en Hospital Clínico. http://www.emol.com/noticias/nacional/2014/05/23/661757/rector-de-la-u.

- School of Law, Universidad Diego Portales. Derechos Humanos de las mujeres. Informe Anual sobre derechos humanos de Chile 2004 Hechos de 2003. 2004; Universidad Diego Portales: Santiago, 227.

- Ministerio de Salud, Ordinario A15/1675, 24 de abril de 2009.

- G. Sandoval, O. Fernández y S. Labrín - 16/05/2014 - 02:15, Salud pide a médicos respetar secreto profesional en casos de aborto. http://www.latercera.com/noticia/nacional/2014/05/680-578333-9-salud-pide-a-medicos-respetar-secreto-profesional-en-casos-de-aborto.shtml.

- Cámara de Diputados. Boletín 6522–11. 2012.

- Cámara de Diputados. Boletin 6591–11. 2012.

- Cámara de Diputados. Boletin 7373–07. 2012.

- Cámara de Deputados. Boletín 8862–11. 2013.

- Cámara de Diputados. Boletín 8925–11. 2013.

- Senado. Boletín 9418–11. 2013.

- Senado. Boletín 9480–11, 2014.

- R Alvarez. Los ejes que marcaron la primera discusión de aborto terapéutico en la Cámara de Diputados. http://www.latercera.com/noticia/politica/2014/06/674-580770-9-los-ejes-que-marcaron-la-primera-discusion-de-aborto-terapeutico-en-la-camara-de.shtml