Abstract

Background

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is usually classified as either variceal or non-variceal. In cirrhotic patients, variceal bleeding has been extensively studied but, 30–40% of cirrhotic patients who bleed have non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) that is frequently caused by gastro duodenal ulcers. Peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB) leads to substantial morbidity and mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Aim

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and outcome of PUB in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Materials and methods

This was a cross-sectional study. Data on cirrhotic patients with PUB over a seven-year period between January 2006 and January 2013 were collected.

Results

Among 103 patients with NVUGIB, 62 patients (60%) having PUB were assessed. Fifty percent were male. Ages ranged from 37 to 72 years, mean 59 ± 7 years. The most common symptom on presentation was hematemesis (53%). Hemodynamic instability on admission was found in 30 patients (48%). Eighteen patients (29%) had initial hemoglobin less than 7 g/dl. Twenty-seven patients (44%) required blood transfusion and the average number of transfused blood units was two. Forty patients (65%) bled from gastric ulcers. Eleven patients (18%) had ulcers with adherent clot. Twenty-four percent of patients had a Rockall score more than five. Five patients (8%) rebled. Complications were reported in seven patients (11%), mainly liver failure. Overall mortality was 8%. Male gender, adherent clot, bleeding recurrence, development of complications during admission and a Rockall score >5 were significant factors for increasing mortality (P = 0.02, 0.016, 0.00001, 0.034 and 0.00003 respectively).

Conclusion

The commonest cause of NVUGIB in patients with liver cirrhosis was PUB. Mortality in patients with PUB was particularly high among males, patients who had adherent clot, bleeding recurrence, development of complications and a high Rockall score.

1 Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding is a common life threatening condition in which mortality rates range from 4% to 15%.Citation1 UGI bleeding is classified according to whether the source of bleeding is variceal or non-variceal. In cirrhotic patients, variceal bleeding has been extensively studied. Nonetheless, 30–40% of cirrhotic patients who bleed have non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB), and it is frequently caused by gastro duodenal ulcers.Citation1

The association of peptic ulcer and liver cirrhosis has been extensively reported in the literature with an incidence varying between 2% and 42%.Citation2 The association of the two diseases is recognized to be a serious problem. Cirrhotic patients with peptic ulcer may be at an increased risk of bleeding due to coagulation dysfunction and thrombocytopenia, conditions that are frequently observed in these patients.Citation3

Schistosomiasis and hepatitis C virus are common diseases in Egypt with hepatitis C virus currently infecting 20.7% of the Egyptian population.Citation4 Bolak Eldakror Hospital is a secondary-care governmental hospital in Giza, Egypt. The gastrointestinal endoscopy unit was set up in 1999. All patients presenting with acute UGI bleeding have been assessed and managed in house since 2004.Citation5,Citation6 A quality controlled disease management protocol for acute bleeding was established with the intention of improving the quality and efficiency of our health care delivery. Clinical guidelines and a clinical care pathway were developed within the availability of local therapeutic options in order to provide a stand-alone practical guide for the team. Patients are classified as being at low or high risk of rebleeding and mortality based on the Rockall risk score (). Patients with a low risk of rebleeding and mortality are discharged home and subsequently undergo diagnostic endoscopy on the next available list. Those at high risk are admitted to the hospital for intensive monitoring and early, energetic resuscitation. Endoscopy is performed on the morning of the second day to establish the diagnosis, to control bleeding and to prevent rebleeding if considered appropriate. As with most government hospitals in Egypt balloon tamponade, vasoactive drugs, IV proton pump inhibitor drugs, surgical shunts, trans-jugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunts and arterial embolization are not locally available.

Table 1 Rockall numerical scoring system.

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and outcome of peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB) in patients with liver cirrhosis.

2 Materials and methods

This was a cross-sectional, hospital based study performed in cirrhotic patients with PUB over a 7-year period between January 2006 and January 2013.

All patients presenting with acute UGI bleeding and a confirmed diagnosis of liver cirrhosis were admitted, assessed and resuscitated in a three-bed intensive-care unit. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed on the basis of clinical and laboratory data and ultrasonography. Histological examination of the liver was not performed. The etiology of the liver disease was not determined in all patients.

Those who were hemodynamically instable (heart rate >100 beats/min, hypotension with a systolic pressure <90 mmHg and/or diastolic value <60 mmHg) were managed with crystalloid solutions with or without blood transfusion. Patients with hemoglobin less than 7 g/dl were transfused according to individual requirements. All patients received prophylactic antibiotic therapy (IV third generation cephalosporin) for suspected variceal bleeding. Endoscopy was performed on the morning of the second day to establish the diagnosis, to control bleeding and prevent rebleeding. All patients had conscious sedation. IV midazolam (2.5 mg) was the agent used for conscious sedation. All endoscopies were performed by two well-trained experienced endoscopists. In patients with ulcers, stigmata of recent bleeding were recorded according to the Forrest classification.Citation7 Active bleeding or visible vessels were classified as high risk stigmata. Endoscopic treatment (epinephrine injection and bipolar probe coagulation) was performed only in these patients. Vigorous water irrigation was performed in all patients with adherent clot to assess the presence of high risk stigmata. During hospitalization patients were closely monitored for rebleeding and complications until discharge. The end point was 2 weeks of follow up or death. Outcomes were analyzed annually and the reports transmitted to an independent experienced gastroenterologist with a particular interest in gastrointestinal bleeding for comment and advice.

2.1 Patients and exclusions

During the study period 500 patients with concomitant acute UGI bleeding and liver cirrhosis were admitted. One hundred and forty-two patients (28%) did not undergo an inpatient endoscopy for various reasons (). Three hundred and fifty-eight patients (72%) did undergo endoscopy of whom 255 (71%) had variceal bleeding and 103 (29%) NVUGIB. Sixty-two patients (60%) with NVUGIB had PUB. Patients who did not undergo endoscopy, had variceal bleeding and NVUGIB other than PUB were excluded from the study. All patients shown endoscopically to have PUB were included in the analysis.

Table 2 Patients with acute UGI bleeding and liver cirrhosis who did not undergo endoscopy.

2.2 Data recording and statistics

A standardized data collection form was completed for each patient. Recorded data included demographic information and historical data: smoking history, drugs used like aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and anticoagulants, alcohol consumption, previous history of peptic ulcer, presenting symptoms and co-morbid illnesses. Physical and laboratory examination findings included hemodynamic data, initial hemoglobin level, resuscitative efforts (blood transfusion requirement), Child-Pugh status and Rockall score. The endoscopic components of the database included the time interval between presentation and endoscopy, identification of the bleeding lesion, description of stigmata of bleeding and method of endoscopic hemostasis if any. Outcomes recorded included the frequency of rebleeding, surgical therapy, complications and mortality. The cause of death and the time interval (in hours) between endoscopy and death were determined.

The data were registered, tabulated and analyzed statistically using a program of SPSS version 15 to calculate frequencies and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. A P value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

3 Results

Among 103 patients with NVUGIB, 62 patients (60%) had PUB (). Peptic ulcer was the commonest cause of NVUGIB in patients with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis (). A total of 62 patients having PUB were studied. Fifty percent were male and 50% female. Ages ranged from 37 to 72 years, mean 59 ± 7 years. Thirty-three patients (53%) aged ⩾60 years. Seventeen patients (27%) had a history of smoking. Thirty-nine patients (63%) were taking aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and two (3%) anticoagulants. Three patients (5%) were consuming alcohol. Ten patients (16%) had a previous history of peptic ulcer. Cirrhosis was newly diagnosed during hospitalization for PUB in ten patients (16%) and had been previously diagnosed in 52 (84%).

Table 3 Endoscopic findings among cirrhotic patients with NVUGIB.

Table 4 Comparison of endoscopic findings among patients with NVUGIB and compensated or decompensated cirrhosis.

The most common symptom on presentation was hematemesis in 33 patients (53%), melena in 15 (24%) and both in 14 (23%). Thirty-two patients (52%) were hemodynamically stable on admission and 30 (48%) were hemodynamically instable. Twenty-eight (45%) patients had compensated cirrhosis and 34 (55%) decompensated cirrhosis. Six patients (10%) had liver failure. Six patients (10%) had hepatocellular carcinoma. Fifteen patients (24%) were Child-Pugh A, 16 (26%) B and 31 (50%) C. Co-morbid illnesses other than liver cirrhosis were documented in 47 patients (76%) (). The mean hemoglobin concentration was 9 ± 3 g/dl, 18 patients (29%) had initial hemoglobin below 7 g/dl. Twenty-seven patients (44%) required blood transfusion; the average number of units given was two.

Table 5 Co-morbidities other than cirrhosis among cirrhotic patients with peptic ulcer bleeding.

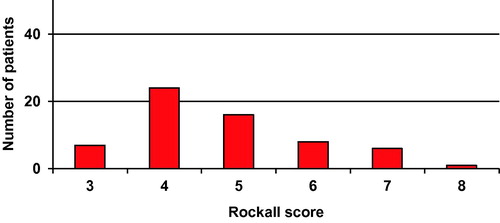

All patients underwent emergency endoscopy during admission. The mean time from presentation to endoscopy was 29 ± 26 h (2–96 h). Endoscopy was conducted within 24 h of presentation in 46 patients (74%). Forty patients (65%) bled from gastric ulcers, 17 (27%) from duodenal ulcers and 5 (8%) from both. Thirty-one patients (50%) had ulcers with clean base, 20 (32%) with pigmented spot and 11 (18%) with adherent clot. Stigmata of portal hypertension (mosaic-like pattern) during endoscopy were documented in 47 patients (76%). Forty-seven patients (76%) had a Rockall score three to five and 15 (24%) six to eight (). The mean full Rockall score was five. Five patients (8%) rebled. Re-endoscopy was performed in two patients (3%) due to rebleeding. Seven patients (11%) developed complications during admission (after endoscopy): liver failure in four patients (6%), deep venous thrombosis in two (3%) and ascites in one (2%). Fifty-seven patients (92%) were discharged. Five patients (8%) died within the 2 weeks of their admission. The time interval from endoscopy to death ranged from 8 to 220 h, mean 78 ± 91 h. Death was due to continuous bleeding in two patients (3%) and comorbid disease in three (5%). One patient died from liver failure, one from pulmonary embolism and one from cardiac arrest.

Mortality was 16% among male patients vs. 0.0% among females (P = 0.02). Mortality was 3% among patients aged less than 60 years vs. 12% aged 60 years or older (P = 0.211). Mortality was 6% among patients with hematemesis vs. 13% with melena vs. 7% with both (P = 0.685). Mortality was 6% among patients who were hemodynamically stable on admission vs. 10% who were hemodynamically instable (P = 0.588). Mortality was 4% in patients with compensated cirrhosis vs. 12% in patients with decompensated cirrhosis (P = 0.238). Mortality was 0% in patients with liver failure vs. 9% in patients without liver failure (P = 0.445). Mortality was 7% in patients with the Child-Pugh group A vs. 6% in patients with B vs. 10% with (P = 0.896). Mortality was 17% among patients had initial hemoglobin below 7 g/dl. vs. 5% who had initial hemoglobin 7 g/dl. or more (P = 0.112). Mortality was 6% among patients with duodenal ulcers vs. 8% with gastric ulcers vs. 20% with both (P = 0.581). Mortality was 0% among patients who had ulcers with clean base vs. 10% with flat pigmented spot vs. 27% with adherent clot (P = 0.016). Mortality was 60% in patients with rebleeding vs. 4% in patients without rebleeding (P = 0.00001). Mortality was 29% in patients with complications vs. 5% in patients without complications (P = 0.034). Mortality was 0.0% among patients who had a low Rockall score (3–5) vs. 33% in those with a high score (6–8) (P = 0.00003).

4 Discussion

Patients with liver cirrhosis may present with gastrointestinal bleeding caused by portal hypertension or by lesions found in patients without cirrhosis. Gastrointestinal bleeding accounts for up to 25% of all mortality in cirrhotic patients, whether compensated or with severe liver disease, and both may be associated with the development of life-threatening complications.Citation8 Excluding variceal bleeding, the most common causes of UGI bleeding in cirrhotic patients are portal hypertensive gastropathy and peptic ulcer disease.Citation8 PUB accounts for 30% of causes of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis, and for 50% of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.Citation9

PUB leads to substantial morbidity and mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis.Citation10 Physiopathology, treatment and prognosis of PUB have never been described in cirrhotic patients as opposed to variceal bleeding. Because cirrhosis is generally an exclusion criterion in randomized controlled trials concerning management of PUB, the efficacy of standard of care needs to be assessed in cirrhotic patients. Moreover, large studies describing the prognosis of PUB treated according to actual recommendations are lacking.Citation10

In the current study we have assessed the prevalence and outcome of PUB in patients with liver cirrhosis. PUB was diagnosed in 17% of patients presenting with acute UGI bleeding and liver cirrhosis and 60% of patients with NVUGIB. Fifty percent of patients were males and 53% aged ⩾60 years. The most common symptom on presentation was hematemesis (53%). Forty-eight percent were hemodynamically instable on admission and 29% had initial hemoglobin below 7 g/dl. Fifty-five percent had decompensated cirrhosis and 50% were Child-Pugh C. Diabetes mellitus was documented in 50%. Sixty-five percent of patients bled from gastric ulcers and 18% had ulcers with adherent clot. Twenty-four percent had a Rockall score >5. Rebleeding occurred in 8% and complications in 11%. The overall mortality was 8%. Death was due to continuous bleeding in 3% and comorbid disease in 5%. The age, mode of presentation of the hemorrhage, hemodynamic instability on arrival, severity of liver disease, initial hemoglobin level or location of bleeding ulcer played no role in mortality. Male gender, endoscopic finding of adherent clot, bleeding recurrence, development of complications during admission and a Rockall score >5 were significant factors for increasing mortality (P = 0.02, 0.016, 0.00001, 0.034 and 0.00003 respectively).

Peptic ulcer was the second commonest cause of bleeding in liver cirrhosis, following varices, and most frequent cause of NVUGIB. Many patients had risk factors associated with peptic ulcer disease. Twenty-seven percent were smokers, 63% were using aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and 5% were consuming alcohol. Sixteen percent had previous history of peptic ulcer. Gastric biopsies were not examined for Helicobacter pylori. In contrast to peptic ulcer disease in the general population, the pathogenic role of Helicobacter pylori in cirrhotic patients remains questionable and may not be a major risk factor for peptic ulcer disease in cirrhotic patients.Citation8,Citation11 it was reported that the role of Helicobacter pylori infection seemed controversial in cirrhotic patients.Citation10 The benefit of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with cirrhosis and peptic ulcer disease has been questioned.Citation11,Citation12 Furthermore, eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with cirrhosis does not effectively reduce the recurrence of peptic ulcers.Citation10 The avoidance of peptic ulcer risk factors, and the early diagnosis and treatment of peptic ulcer when present in liver cirrhosis patients are important to prevent complications (bleeding and mortality).

Co-morbid illnesses other than liver cirrhosis were documented in 76% of patients. Many patients had multiple co-morbidities. Diabetes mellitus was the commonest co-morbid disease (50%). It was reported that up to 96% of patients with cirrhosis may be glucose intolerant and 30% may be clinically diabetic.Citation13 Currently, it is a matter for debate whether type 2 diabetes mellitus in the absence of other risk factors contributing to metabolic syndrome (obesity and hypertriglyceridemia), could be a risk factor for the development and progression of liver disease.Citation14–Citation16 On the other hand, the diabetes which develops as a complication of cirrhosis is known as “hepatogenous diabetes” and is not recognized by the American Diabetes Association and the World Health Organization as a specific independent entity.Citation17 It was also reported that the prevalence of diabetes was much higher in hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis and alcoholic liver disease, but not in cholestatic liver disease suggesting the important role of underlying cause in the development of diabetes in these patients.Citation18

Fifty percent of patients had ulcers with clean base, 32% with pigmented spot and 18% with adherent clot. Endoscopic finding of adherent clot was predictive of mortality of PUB. No high risk bleeding stigmata were identified in any patient with PUB. These may have been missed because endoscopy was performed on the morning of the second day and not on admission. During the study period, 9% of cirrhotic patients admitted to our hospital with acute UGI bleeding died rapidly after admission without having undergone an endoscopy due to continued bleeding or rebleeding (for which reason they were not included in the study). The mean time from admission to death was 6 h (range 25 min–18 h). We intend in future to perform endoscopy as soon as patients have been resuscitated and are stable.

Re-bleeding occurred in 8% of patients and 11% developed complications during admission (mainly liver failure). Rebleeding and complications were predictive of mortality of PUB. It was reported that re-bleeding occurred in 7% of patients with PUB and liver cirrhosis.Citation10 Maximum nonsurgical treatment for PUB, including arterial embolization, should always be applied to patients with cirrhosis.Citation10 Recent data indicate that most PUB-linked deaths are not direct sequelae of the bleeding ulcer itself. Instead, mortality derives from multi-organ failure or cardiopulmonary conditions suggesting that improving treatments for the bleeding ulcer may impact mortality by very little.Citation20 Recognizing this possibility is paramount for the implementation of strategies that provide supportive care and prevent complications and key-organ failure, as well as treat the ulcer.Citation19

Mortality occurred in 8% of patients. Forty percent of the deaths were directly related to the bleeding episode, whilst the remaining deaths were associated with co-morbidities. Mortality is similar to that reported in PUB without liver cirrhosis. Despite recent improvement in PUB management, mortality of PUB remains high, ranging from 5% to 10%.Citation20 Co-morbidity is an important predictor of death in all patients with gastro intestinal bleeding, in a recently published study of 10,428 patients with NVUGIB in non-cirrhotic patients, death was associated with causes directly related to the bleeding episode in only 29% of cases whilst in the remaining cases, co-morbidity played a fundamental role.Citation21

A high Rockall score was predictive of mortality of PUB. The effectiveness of Rockall score as a predictor of in-hospital death in cirrhotic patients with PUB proved to be similar to that reported in non-cirrhotic patients.Citation22 The Rockall scoring system is a widely validated scoring system which was principally designed to predict death based on a combination of clinical and endoscopic findings. Surprisingly, mortality was not related to the severity of liver dysfunction as expressed by clinical and laboratory criteria (Child-Pugh classification). The Child-Pugh classification has an advantage over other classifications in that all patients can be classified even when some data are not (yet) available.Citation8 However all classification systems have a margin of false positive and false negative prediction.Citation8 A score system based on one population may not be applicable to others. The main purpose of a clinical classification system in this context is to provide a wider and more objective approach to decision-making in the treatment of these very difficult patients.Citation8

5 Summary

This study was performed in a community hospital in Egypt. It showed that the commonest cause of NVUGIB in patients with liver cirrhosis was PUB. PUB was associated with life-threatening complications. Male gender, adherent clot, bleeding recurrence, development of complications and a high Rockall score were predictive of mortality of PUB. Many patients had a risk factor associated with peptic ulcer disease. Avoiding risk factors, early diagnosis and treatment of peptic ulcer in cirrhotic patients are important to prevent complications and must be emphasized to all physicians.

6 Conclusion

The commonest cause of NVUGIB in patients with liver cirrhosis was PUB. Mortality in patients with PUB was particularly high among males, patients who had adherent clot, bleeding recurrence, development of complications and a high Rockall score.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Dr. Samaa H. Hosny, Cairo University, for statistical assistance.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Alexandria University Faculty of Medicine.

Available online 31 January 2014

References

- J.GonzálezD.García-CompeanG.Vázquez-ElizondoA.Garza-GalindoJ.Jáquez-QuintanaH.Maldonado-GarzaNonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clinical features, outcomes and predictors of in-hospital mortality. A prospective studyAnn Hepatol102011287295

- Massive non-variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis [internet]. 2012 December. Available from: http://repub.eur.nl/res/pub/10431/771111_Urk,%20Hero%20van.pdf.

- S.BasiliV.RaparelliF.VioliThe coagulopathy of chronic liver disease: is there a causal relationship with bleeding? YesEur J Intern Med2120106264

- S.ZakariaR.FouadO.ShakerW.El AkelA.HashemS.El AideThe natural history of untreated symptomatic acute hepatitis C infection in EgyptArab J Gastroenterol22005131139

- A.GadoB.EbeidA.AbdelmohsenA.AxonClinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage among patients admitted to a government hospital in EgyptSaudi J Gastroenterol1820123439

- A.GadoB.EbeidA.AbdelmohsenA.AxonThe management of low-risk acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the community in EgyptAlexandria J Med492013195198

- J.A.ForrestN.D.FinlaysonD.J.ShearmanEndoscopy in gastrointestinal bleedingLancet21974394397

- M.KalafateliC.K.TriantosV.NikolopoulouA.BurroughsNon-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis: a reviewDig Dis Sci57201227432754

- G.I.KirchnerW.BeilJ.S.BleckM.P.MannsS.WagnerPrevalence of Helicobacter pylori and occurrence of gastroduodenal lesions in patients with liver cirrhosisInt J Clin Exp Med420112631

- M.RudlerG.RousseauH.BenosmanJ.MassardL.DeforgesP.LebrayPeptic ulcer bleeding in patients with or without cirrhosisAliment Pharmacol Ther3622012166172

- R.VillalanN.K.MarojuV.KateN.AnanthakrishnanIs Helicobacter pylori eradication indicated in cirrhotic patients with peptic ulcer disease?Trop Gastroenterol2720066668

- Shafi F, Asad R, Azam M, Aftab M. Frequency of duodenal ulcer in cirrhosis of liver [internet]. 2012 December. Available from: http://pjmhsonline.com/frequency_of_duodenal_ulcer_in_c.htm.

- I.J.HickmanG.A.MacdonaldImpact of diabetes on the severity of liver diseaseAm J Med1202007829834

- H.B.El-SeragT.TranJ.E.EverhartDiabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinomaGastroenterology1262004460468

- K.G.TolmanV.FonsecaA.DalpiazM.H.TanSpectrum of liver disease in type 2 diabetes and management of patients with diabetes and liver diseaseDiabetes Care302007734743

- H.B.El-SeragJ.E.EverhartDiabetes increases the risk of acute hepatic failureGastroenterology122200218221828

- A.HolsteinS.HinzeE.ThiessenA.PlaschkeE.H.EgbertsClinical implications of hepatogenous diabetes in liver cirrhosisJ Gastroenterol Hepatol172002677681

- N.N.ZeinA.S.AbdulkarimR.H.WiesnerK.S.EganD.H.PersingPrevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with end-stage liver cirrhosis due to hepatitis C, alcohol, or cholestatic diseaseJ Hepatol322000209217

- A.LanasEditorial: upper GI bleeding-associated mortality: challenges to improving a resistant outcomeAm J Gastroenterol105120109092

- Y.C.HsuJ.T.LinT.T.ChenM.S.WuC.Y.WuLong-term risk of recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis: A 10-year nationwide cohort studyHepatology5622012698705

- J.J.SungK.K.TsoiT.K.MaM.Y.YungJ.Y.LauP.W.ChiuCauses of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 casesAm J Gastroenterol10520108489

- Z.A.SaeedC.B.WinchesterP.A.MichaletzA scoring system to predict rebleeding from peptic ulcer: prognostic value and clinical applicationsAm J Gastroenterol88199318421849