Abstract

Objective:

To conduct a prospective randomised study comparing the safety, effectiveness and treatment outcomes in patients undergoing bipolar transurethral resection of the prostate (bTURP) and photoselective vaporisation of the prostate (PVP) under sedoanalgesia, as sedoanalgesia is a safe and effective technique suitable for minimally invasive endourological procedures and although studies have confirmed that both TURP and PVP are feasible under sedoanalgesia there are none comparing the two.

Patients and methods:

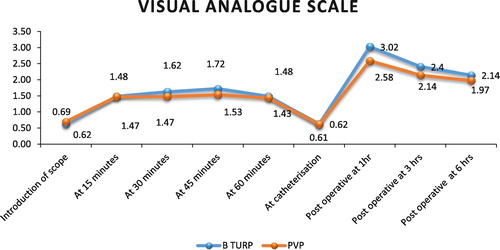

Between November 2014 and April 2016, all patients satisfying the eligibility criteria underwent either bTURP or PVP under sedoanalgesia after randomisation. The groups were compared for functional outcomes, visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores (range 0–10), perioperative variables and complications, with a follow-up of 3 months.

Results:

In all, 42 and 36 patients underwent bTURP and PVP under sedoanalgesia, respectively. The mean VAS pain score was <2 at any time during the procedure, with no conversions to general anaesthesia. PVP patients had a shorter operating time [mean (SD) 55.64 (12.8) vs 61.79 (14.2) min, P = 0.035], shorter duration of hospitalisation [mean (SD) 14.58 (2.81) vs 19.21 (2.82) h, P < 0.001] and a higher dysuria rate when compared to bTURP patients. However, the catheterisation time was similar and both intraoperative and postoperative complications were minimal and comparable. Improvements in the International Prostate Symptom Score, quality of life, prostate volume, maximum urinary flow rate and post-void residual urine volume at 3 months were similar in both groups. None of our patients required re-admission or re-operation.

Conclusion:

Both PVP and bTURP can be carried out safely under sedoanalgesia with excellent treatment outcomes.

Introduction

Day care procedures are becoming increasingly popular due to the benefits of a short hospital stay, less morbidity, early ambulation, and increased cost-effectiveness [Citation1]. Such procedures when performed under sedoanalgesia allow patients to tolerate painful procedures, whilst maintaining adequate cardiorespiratory function and consciousness [Citation2]. Sedoanalgesia is safe, effective, less time consuming, and is particularly suitable for minimally invasive endourological procedures [Citation1,Citation2].

Many patients who undergo surgery for BPH have associated comorbidities and are deemed unfit for general anaesthesia. In such a scenario, sedoanalgesia seems to be a promising option, enabling faster recovery and shorter hospitalisation [Citation3]. Data accumulated over the years have reported favourable results [Citation4,Citation5] for both PVP and TURP under sedoanalgesia, with excellent intraoperative safety and expedient postoperative recovery. However, the studies are few and require further validation in terms of the safety of the techniques. Therefore, we conducted a prospective randomised study to compare the safety, effectiveness and treatment outcomes in patients undergoing bipolar TURP (bTURP) and photoselective vaporisation of the prostate (PVP) for BPH, under sedoanalgesia, in carefully selected patients.

Patients and methods

The study protocol and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Between November 2014 and April 2016, consecutive patients attending the Urology Out-patient Department with LUTS secondary to benign prostatic enlargement who were planned for surgery according to the AUA International BPH Guidelines were included in this prospective, randomised study. The inclusion criteria were: age >50 years, prostate volume ranging between 20 and 50 mL, IPSS of >7, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) of <15 mL/s, serum PSA level of <4 ng/mL, histologically benign enlargement of the prostate when the serum PSA level was >4 ng/mL, and failure of medical management. The exclusion criteria were: history of prostate, bladder or urethral surgery; neurogenic bladder dysfunction; patients in whom anticoagulants could not be safely discontinued before surgery; active UTI; presence of bladder calculi; urethral stricture disease; and biopsy confirmed carcinoma of the prostate.

Initial evaluation included a detailed clinical history including the completion of the IPSS; physical examination including DRE and focused neurological examination; complete haemogram; serum creatinine; serum electrolytes; urine analysis; serum PSA measurement; ultrasonography of the kidney, ureter, and bladder region to assess the prostate size, the upper tract, back pressure changes in the bladder, post-void residual urine volume (PVR) and to look for the presence of calculi; and Qmax measurement on uroflowmetry. Eligible patients were randomised to one of the two groups. Group A, underwent bTURP; and Group B, underwent PVP with a potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) 120W (high performance system) laser. Randomisation was done in a 1:1 ratio using a sealed envelope sequence.

A pre-anaesthetic evaluation was conducted before admission/procedure in all patients. All patients were admitted to the hospital on the day of the proposed surgery after fasting for 4–6 h. Patients were advised to take two tablets of laxative and an anxiolytic the night preceding surgery, and to take a scrub bath in the morning before admission. Informed written consent for the proposed procedure was taken, followed by part preparation in the preoperative room just before the procedure. An i.v. antibiotic was given followed by sedoanalgesia. Under the supervision of an experienced anaesthesiologist, sedation and anxiolysis were obtained with i.v. pentazocine (0.5 mg/kg) and promethazine (1 mg/kg). Local anaesthesia comprised three parts. Firstly, lignocaine jelly 2% was topically instilled into the urethra for ≥10 min. Secondly, infiltration of 1% lignocaine (100–200 mg) into the prostate and periprostatic area via the perineal route. Thirdly, an intraprostatic block was given, where 5 mL 1% lignocaine (100–200 mg) was injected into the bladder neck at the 9- and 3-o’clock positions subtrigonally under cystoscopic guidance. The cystoscope was then withdrawn until the verumontanum was visualised and 5 mL infiltrated into the floor of the bladder neck and prostate at the 5- and 7-o’clock positions adjacent to the verumontanum. Midazolam (i.v.) was added if the desired effect was not achieved by the above mentioned procedure.

In the bTURP group, a Plasma-sect electrode was used as the cutting element and saline was used as the irrigant. The middle lobe was resected first, followed by an excavation between the 5- and 7-‘o clock positions up to the surgical capsule. The side lobes and the ventral part of the gland were then resected, with the apical glands resected last. For the PVP group, a continuous flow 21-F laserscope with a 30-° lens was used and 0.9% saline used as the irrigant. A 600-µm side-firing laser fibre, emitting green light at 532 nm, was used and tissue vaporised down to the prostatic capsule until an unobstructed view of the trigone and a TURP-like cavity was obtained. Vaporisation was achieved by moving the laser fibre slowly and constantly in a ‘paint brush fashion’. Bleeding vessels encountered during vaporisation were coagulated by defocusing the laser fibre (increasing working distance to 3–4 mm) or by reducing the power setting to ∼ 30 W. On achieving complete haemostasis, after both bTURP and PVP, a 22-F three-way catheter was inserted into the bladder, the bulb inflated to a maximum of 50 mL, traction given, and postoperatively the bladder was irrigated with 0.9% saline until clear effluent was seen.

Intraoperative factors assessed were operative time; pain score/discomfort; amount of irrigation and i.v. fluids used; requirements of any blood transfusion; and intraoperative complications, such as bleeding and capsular/venous sinus perforation; and TUR syndrome. Pain was assessed using a visual analogue scale (VAS; range 0–10) at the introduction of the scope and then every 15 min for up to 60 min resection, and finally at catheterisation. Adverse effects of anaesthesia e.g. rise or fall in blood pressure, bradycardia, tachycardia, nausea/vomiting, and alterations in oxygen saturation, were recorded. Postoperatively a note was made of the amount and duration of irrigation; traction time; clot retention; VAS pain score at 1, 3 and 6 h; requirement of analgesics; decrease in haemoglobin; and electrolyte imbalance. Patients were discharged once the urine was clear after discontinuing irrigation for 2 h. The catheter was removed postoperatively from 6 h onwards. Those patients who failed trial without catheter were re-catheterised and a voiding trial was repeated after 5 days. An oral antibiotic was given for 5 days after catheter removal. All patients were followed-up regularly in the Urology Outpatient Department at 1 and 3 months postoperatively with the IPSS, dysuria scores, Qmax and PVR assessment. Dysuria was scored on a 1–10 scale. Any complications in the postoperative period were noted and dealt with accordingly.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS® version 21.0, SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) and median. Normality of data was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. If the normality was rejected then a non-parametric test was used. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In all, 84 patients were eligible and randomised; 42 patients each to bTURP (Group A) and PVP (Group B) groups, respectively. Six patients from Group B dropped out from the study after randomisation. Thus, 78 patients were available for analysis, 42 in the bTURP group and 36 in the PVP group, respectively.

The mean (SD) age of the study population was 65.32 (8.71) years. The mean serum creatinine level was 0.94 (0.27) mg/dL, the mean (SD) haemoglobin level was 13.08 (1.33) g/dL and the mean (SD) serum sodium level was 138.07 (4.02) mmol/L. The mean (SD, range) serum PSA level was 2.44 (1.62, 0.24–8.91) ng/mL. All patients had associated comorbidities including: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease. The demographic profiles of the study population across both groups were comparable ( and ).

Table 1 Demographic profile of the study population (N = 78).

Table 2 Distribution of preoperative characteristics across the study population (N = 78).

The VAS pain score during the procedure was sub-classified into: ‘no pain’, ‘mild pain’, ‘moderate pain’, and ‘severe pain’ (). In all, 11 patients who experienced ‘moderate pain’ received a supplemental dose of i.v. promethazine and pentazocine that ameliorated the discomfort, and the procedure was completed safely with no further complaints. The mean VAS pain score assessed at various points was <2 at all times during the procedure (). Intraoperative anaesthesia-related adverse effects, such as hypertension/hypotension, nausea/vomiting, change in oxygen saturation, were found to be minimal and comparable across the treatment groups (). Postoperatively, pain was assessed using the same VAS at 1, 3 and 6 h. The mean number of analgesic doses required across the groups was less than two until discharge. There were no conversions to general or regional anaesthesia.

Table 3 Classification of intraoperative VAS pain scores.

Table 4 Distribution of anaesthetic complications across the two treatment groups (N = 78).

Data pertaining to the perioperative period are summarised in . Operative time (inclusive of time required to give local anaesthesia and a wait time of 10 min) was significantly longer in Group A (bTURP) when compared to Group B (PVP), at a mean (SD) of 61.79 (14.2) vs 55.64 (12.8) min (P = 0.035). The amount and duration of intraoperative and postoperative irrigation, along with the traction time were all significantly lesser in Group B (PVP) as compared to Group A (bTURP). The mean (SD) duration of hospital stay was also significantly lesser in the Group B, at 14.58 (2.81) vs 19.21 (2.82) h (P < 0.001). However, the catheterisation time was found to be comparable across both the treatment groups, at a mean (SD) of 1.05 (0.22) vs 1.03 (0.17) days (P = 0.652). All our patients were conscious and well oriented at the time of discharge.

Table 5 Intraoperative and immediate postoperative variables in the two treatment groups (N = 78).

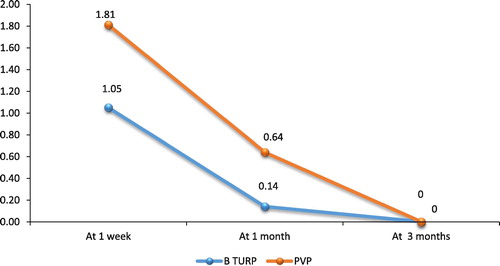

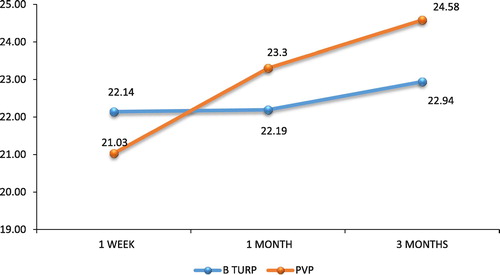

The procedural complications (both intraoperative and postoperative) are summarised in . Dysuria in the early postoperative period (at 1 week) was significantly more common in Group B as compared to Group A (), at a mean (SD) of 2.1 (1) vs 3.25 (1.373) (P < 0.001), which completely resolved by the 3-month follow-up. The Qmax was comparable between the two groups, with no statistically significant difference (). The mean percentage fall in prostate volume at the 3-month follow-up was comparable, at 70.94% in the Group A and 68.19% in Group B.

Table 6 Surgical complications in the two treatment groups (N = 78).

Discussion

The use of sedoanalgesia in endourological practice has risen over the last decade with the increase in office-based procedures. This can potentially decrease the cost and lessen the burden on the operating room and recovery room. Repeated cystoscopies performed for the follow-up of bladder tumour brought about the possibility of performing cystoscopy under sedoanalgesia, with or without transurethral resection of bladder tumour. Some of the standard procedures currently being used include TRUS-guided biopsy, flexible cystoscopy, percutaneous nephrostomy, percutaneous cyst aspiration, renal biopsy, and various scrotal procedures. Procedures such as optical urethrotomy, rigid cystoscopy, bladder biopsy, ureteroscopy, transurethral incision and resection of the prostate, and resection of bladder tumours are also being performed under sedoanalgesia without any serious complications. Safety, effectiveness and low cost, make sedoanalgesia a preferable alternative to general or spinal anaesthesia for many urological procedures [Citation6]. Moreover, sedoanalgesia should be considered in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities thus minimising morbidity and hastening recovery [Citation3]. It is an ideal form of anaesthesia for day care procedures, as most of the patients will be alert and well oriented in a few hours. In an institution like ours, i.e., a tertiary hospital with a heavy work load and long theatre-waiting list, it may also result in greater work output per day leading to a reduction in the waiting list [Citation7]. However, there has been a reluctance to perform urological procedures under sedoanalgesia for fear of intraoperative pain, patient discomfort, nausea, vomiting, poor cooperation, dissatisfaction of the patient, or respiratory complications (airway obstruction or desaturation) [Citation8]. The selection of the patient appears to be a significant factor in avoiding these complications and a procedural duration of 60–90 min is considered to be the time limit for regional anaesthesia [Citation7].

Many patients undergoing TURP/PVP for prostatomegaly with indications for surgery are aged >50 years with coexisting medical conditions and are unfit for general anaesthesia. In such patients sedoanalgesia can be considered. Birch et al. [Citation9], in their study comprising 100 patients, proved that sedoanalgesia is safe and acceptable to all patients regardless of their pre-existing medical condition(s). However, this applied to patients where the weight of prostate resected was <40 g. Similarly, PVP with the patient under local peri-prostatic infiltration anaesthesia with light sedation has been reported to be safe and effective [Citation5]. We compared the effectiveness of sedoanalgesia for both bTURP and PVP for smaller prostates (<50 mL) and the short-term outcomes of both the procedures were evaluated.

In our present study, none of the patients had to be converted to general or spinal anaesthesia. The only problem that the patients reported was the sensation of bladder fullness throughout the procedure. To overcome this, Sinha et al. [Citation10] used a suprapubic catheter for continuous bladder drainage in patients within small volume bladders. However, this was not necessary in our present patients, where an assistant gently palpated the patient’s suprapubic region during the procedure for evidence of bladder distension. The mean VAS pain score was not >2 at any time during the procedure. If the patients complained of pain, a supplemental dose of sedative was given. Poor cooperation/failure of the procedure, which usually requires conversion to general anaesthesia, did not occur in the present cohort. A minority of our patients had tachycardia, change in blood pressure, and nausea/vomiting during the procedure. Hypertension was managed with sublingual nifedipine and i.v. furosemide (20 mg), and anti-emetics were given for patients with nausea/vomiting. None of our patients had bradycardia or a change in oxygen saturation. Birch et al. [Citation9] have reported similar results with the use of sedoanalgesia and concluded its safety.

We further evaluated the perioperative and postoperative complications in relation to the surgical procedures performed across both the treatment groups. None of our present study population required blood transfusion or developed TUR syndrome in the perioperative period. Laser techniques and bTURP have eliminated the incidence of TUR syndrome, as the irrigant solution used is saline [Citation11,Citation12]. There is also reduced absorption due to simultaneous robust coagulation underneath whilst cutting or vaporising [Citation12]. A meta-analysis by Ahyai et al. [Citation13] reported an overall treatment-specific intraoperative complication rate of 3–3.5% for TURP, PVP and holmium laser enucleation of the prostate, which included bleeding, capsular perforation, conversion to TURP, injury of the mucosa, and blood transfusion or TUR syndrome. PVP reportedly has the highest UTI and re-catheterisation rates, amounting to 20–25% of the early complication rate [Citation14]. In comparison, our present study had fewer adverse events. None of our patients had fever, sepsis or clot retention, and none required re-catheterisation or had secondary bleeding. There was no difference in the stricture incidence, bladder neck stenosis, requirement of re-operation, or incontinence across both the groups. However, long-term follow-up would be required to assess the exact incidence of complications across both groups. A higher rate of dysuria was noted in the KTP-PVP patients. Dysuria might be caused by necrotic prostatic tissue, oedema of the prostatic urethra, infection, and perhaps, most importantly, incomplete ablation of prostatic tissue [Citation15].

The subjective voiding variables showed dramatic improvement when compared with the preoperative values. The mean IPSS was 3.95 in the bTURP group and 3.78 in the PVP group (P = 0.397). The mean PVR on ultrasonography was 8.76 and 10.39 mL in the TURP and PVP groups, respectively. Our present study demonstrated a large reduction in prostate volume, which was comparable across both the groups. Both bTURP and PVP improve subjective and objective variables with similar outcomes when compared [Citation16].

Patients’ overall satisfaction with the anaesthetic and surgical management was assessed, and this was graded as: ‘complete satisfaction’, ‘partial satisfaction’, or ‘not satisfied at all’. Overall satisfaction was acceptable (88.46%). A reason for the high satisfaction rate may be that our present patients were carefully selected by the surgeon and the operative team, and they were well prepared with detailed preoperative counselling for the treatment procedure.

Limitations of the study

| 1. | We had a short follow-up of only 3 months. Long-term results of the study need to be evaluated. | ||||

| 2. | Prostate volumes of >50 mL were excluded from our present study. Further studies including larger prostates and larger cohorts should be investigated. | ||||

Conclusion

The present study shows that both bTURP and PVP are feasible under sedoanalgesia in carefully selected patients with a prostate volume of <50 mL, with a high rate of patient satisfaction, less time to discharge, and excellent treatment outcomes. PVP has a shorter operative time, traction time, duration of irrigation and duration of hospital stay as compared to bTURP.

Conflict of interest

None.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- H.S.QubbajCystoscopy and TURT using sedoanalgesia: experience in 398 patientsJ Postgrad Med Instit1020032426

- S.RaoS.PunekarG.SwamiJ.S.KinneS.KarhadkarSedoanalgesia in endourology. IndianJ Urol1720004143

- T.P.BriggsK.M.AnsonA.JonesB.J.CokerR.A.MillerUrological day case surgery in elderly and medically unfit patients using sedoanalgesia: what are the limits?Br J Urol751995708711

- J.ChanderU.GuptaR.MehraV.K.RamtekeSafety and efficacy of transurethral resection of the prostate under sedoanalgesiaBJU Int862000220222

- J.M.PedersenP.R.RomundstadJ.G.MjønesC.J.Arum2-year follow-up pressure flow studies of prostate photoselective vaporization using local anesthesia with sedationJ Urol181200917941799

- B.R.BirchK.M.AnsonR.A.MillerSedoanalgesia in urology: a safe, cost-effective alternative to general anaesthesia. A review of 0 casesBr J Urol661990342350

- A.MalikF.OzairA.AhsanR.AhmadSedoanalgesia for day case proceduresJ Postgrad Med Instit111997130132

- U.I.AbotalebG.F.AmerO.S.MetwallyA.A.HegazyAM.ElsaidPatients' satisfaction with sedoanalgesia versus subarachnoid analgesia in endourologyEgypt J Anaesth272011151155

- B.R.BirchJ.S.GelisterC.J.ParkerH.ChaveR.A.MillerTransurethral resection of prostate under sedation and local anesthesia (Sedoanalgesia). Experience in 100 patientsUrology381991113118

- B.SinhaG.HaikelP.H.LangeT.D.MoonP.NarayanTransurethral resection of the prostate with local anesthesia in 100 patientsJ Urol1351986719721

- Je-NicolasCornuA systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic obstruction: an updateEur Urol67201510661096

- H.S.HoC.W.ChengBipolar transurethral resection of prostate: a new reference standard?Curr Opin Urol1820085055

- S.A.AhyaiP.GillingS.A.KaplanR.M.KuntzS.MadersbacherF.Montorsiet al.Meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic enlargementEur Urol582010384397

- H.DingW.DuZ.P.LuZ.X.ZhaiH.Z.WangZ.P.WangPhotoselective green-light laser vaporisation vs. TURP for BPH: Meta-analysisAsian J Androl142012720725

- N.K.MohantyP.VasudevaA.KumarS.PrakashM.JainR.P.AroraPhotoselective vaporization of prostate vs. transurethral resection of prostate: a prospective, randomized study with one year follow-up IndianJ Urol282012307312

- S.SpataforaA.CasaricoA.FandellaC.GalettiR.HurleE.Mazziniet al.Evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms related to uncomplicated benign prostatic hyperplasia in Italy: updated summary from AURO.it. TherAdv Urol42012279301