?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Polycaprolactone/Polymethylmethacrylate (PCL/PMMA) biopolymer blend can be prepared by casting technique. Structural, optical and thermal properties of the blend have been studied using X-ray diffraction (XRD), infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). XRD show two diffraction peaks at 2θ = 21.4° and 23.8° which attributed to the planes (110) and (200) that represent crystallographic planes of semi-crystalline PCL, respectively, where PMMA revealed a broad amorphous hump observed around 2θ = 15°. The FTIR spectra showed some variations in the position and intensity of some absorption bands which reveal an interaction and good miscibility between the two polymers. TGA suggested that the thermal stability increases with increasing PCL concentration; this indicates the incorporation of PCL into the host. Approximately the pure PCL mass loss remains constant until complete decomposition occurs at about 430 °C, whereas PMMA complete decomposition occurs at about 400 °C. So, decomposition temperature of PCL is higher than PMMA by nearly 30 °C.

Keywords:

1 Introduction

Blending between two or more polymers can modify the structural and physical properties of polymers to specific requirements. So, the attention of material researchers has been attracted to polymers blend [Citation1–Citation[2]Citation[3]Citation4]. It involves physical mixing of biopolymers, leading to creation of a new material having some desirable properties that are superior to any one of the component polymers [Citation5–Citation[6]Citation7]. Manifestation of these properties depends on the miscibility of homo-polymers at the molecular scale, so that miscibility leads to variation of the blend's morphology, ranging from a single phase system to a two phase or multiphase systems [Citation6]. The basis of biopolymer miscibility may arise from several different interactions, like charge transfer complexes for homo-polymer mixtures, hydrogen bonding and dipole–dipole forces [Citation5]. Polycaprolactone (PCL) is a semi-crystalline aliphatic polymer with the chemical formula (C6H10O2)n. It has a low melting point (60°C) and glass transition temperature equals −60 °C. PCL also have suitable properties such as good biocompatibility, good biodegradability, good mechanical strength and remarkable toughness. Owing to its hydrophobic nature PCL has a good solubility in chloroform and tetrahydrofuran (THF). As the molecular weight increases, PCL crystallinity tends to decrease [Citation8–Citation[9]Citation[10]Citation11]. Blend compatibility has made PCL a continuous research focus in the biomedical application. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) is a linear thermoplastic polymer with the chemical formula (C5H8O2)n. It has a melting point equal to 160 °C and a glass transition temperature of 85 °C. PMMA has been widely used as a biomaterial in medical applications and in some optical systems (manufacturing of contact lens as transmit light up to 93%) [Citation12]. It also can be used as denture base material due to its favorable properties, including ease of handling and repair, as well stability in the oral environment [Citation13]. PCL is selected as one of the blend components in view of its miscibility with PMMA to introduce a modern category of biopolymer blends with a simple method of preparation suitable for being used in some biological application. This work aims to investigate both compatibility and phase behavior of PCL/PMMA bioblends to obtain a critical concentration with the best overall good properties to use later with some addition of organic or inorganic materials for some application.

2 Experiment and method

2.1 Materials

The chemicals used were Poly ε-caprolactone pellets (Mw~80,000, Sigma-Aldrich and Lot No. MKBP7389V), polymethylmethacrylate (Mw~120,000, Sigma-Aldrich and Lot No. MKBB7676) and chloroform solution as a solvent (HPLC grade, Fisher Chemical and Lot No. 1229720).

2.2 Sample preparation

Polycaprolactone/Polymethylmethacrylate bioblends prepared via casting technique and mixtures of the PCL/PMMA blend films were dissolved in a glass beaker by chloroform using a magnetic stirrer for 45 minutes until complete miscibility [Citation14] occurred and placed in an 8-cm diameter Petri dish (The Petri dishes were cleaned with chloroform and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 20 minutes). After evaporation of the solvent, bio-blend films were kept to dry at room temperature for one day.

2.3 Physical measurements

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) scans were obtained using PANalytical X'Pert PRO XRD system using the radiation of Cu Kα X-ray where the tube operated at 30 kV, Bragg's angle 2θ in the range of 3–60°, λ = 1.54 Å. FTIR absorption spectra were achieved utilizing the single beam Fourier transform-infrared spectrometer (FTIR-Nicolet is10). FTIR spectra of the samples were obtained in the spectral range of 4000–500 cm−1. UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured in the wavelength region of 200–600 nm using spectrophotometer (T80+, UV/Vis. spectrometer, PG Instrument Ltd.) to retrace the structural changes due to different blend concentrations and their optical properties. A Perkin–Elmer (US, Norwalk, CT) TGA-7 was used for the thermogravimetric analysis of the samples. For the data analysis a small amount of (mg) sample was taken and the samples were heated at room temperature of 500 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min in nitrogen atmosphere.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 X-ray diffraction analysis

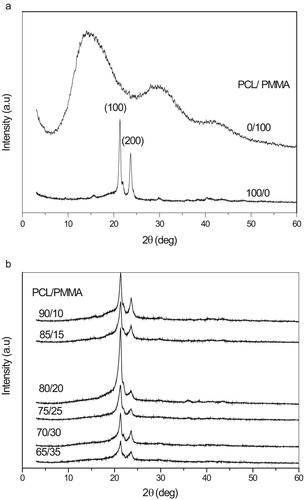

The XRD diffraction scans of the biopolymer blend are also used as a criterion to determine its overlap and homogeneity. If two biopolymers have low biocompatibility and are immiscible, then each biopolymer would have its own crystal region in the blend films. Fig. 1a shows two characteristic peaks at angles 2θ = 21.4° and 23.8°, corresponding to the (110) and (200) crystallographic planes of semi-crystalline nature of PCL biopolymer, respectively [Citation15]. The observed scans of pure PMMA as shown in Fig. 1a exhibits a characteristic broad amorphous hump observed around 2θ = 15°, 30.2° and also a weak hump observed at about 2θ = 42.2° [Citation16,Citation17].

XRD diffraction scans of PCL/PMMA blend are depicted in Fig. 1b. It is clear that the maximum sharp peak intensity at PCL/PMMA 80/20 which leads to exhibit a maximum degree of crystallinity is due to increasing the degree of ordering of atoms at PCL/PMMA blend at 80/20. Also it is observed that the XRD patterns of the PCL/PMMA blend films still kept the characteristic two peaks of pure PCL, but the characteristic two peaks of pure PMMA that disappeared indicate the miscibility among two biopolymers, which means that the incorporation PMMA did not significantly affect the crystalline structure of PCL [Citation18].

3.2 Infrared spectroscope analysis

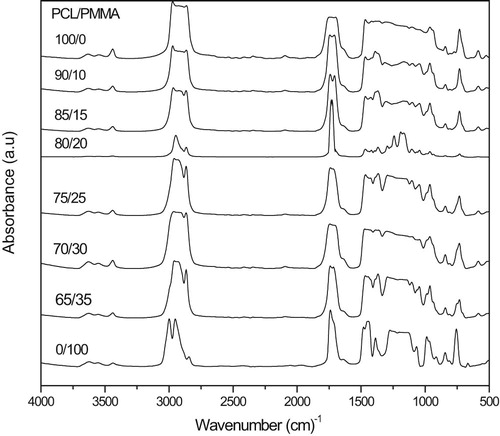

In this paper FTIR spectra are used to investigate the incorporation of PCL into the PMMA biopolymer matrix. Fig. 2 shows the FTIR absorption spectra of PCL/PMMA biopolymer blend films. There are characteristic three peaks of PMMA that appear at 1071, 985, and 844 cm−1 [Citation19,Citation20], whereas the absorption band at 1159, 1442, 1723, and 2951 cm−1 are assigned to O–CH3 stretching, CH3 stretching, C=O stretching, and C–H asymmetric stretching vibrations in PMMA, respectively [Citation21] ( and ).

Table 1 Vibrational modes and wave numbers exhibited by pure PMMA.

Table 2 Vibrational modes and wave numbers exhibited by pure PCL.

On the other hand, PCL spectrum display characteristic peaks of C=O stretching vibrations at 1726 cm−1, CH2 bending modes at 1361, 1397 and 1473 cm−1 and CH2 asymmetric stretching at 2942 and symmetric stretching at 2862 cm−1. The C–O–C stretching vibrations yield peaks at 1042, 1107 and 1233 cm−1. The bands at 1160 and 1290 cm−1 are assigned to C–O and C–C stretching in the amorphous and in the crystalline phases, respectively [Citation22]. As shown in Fig. 2, bioblends display triple split band identified at about 3465, 3535 and 3637 cm−1; this is the C–H stretching band. Typical C–H stretching is usually present as a distinctively large band above 3000 cm−1. Some bands disappear, others have their intensity changed and a new absorption peak appear at nearly 1200 cm−1; this is a good evidence for compatibility between PCL and PMMA. From Fig. 2 the minimum bands appeared at 80/20. This reveals compatibility between the origin of the IR and X-ray response of the present PCL/PMMA system.

3.3 UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis

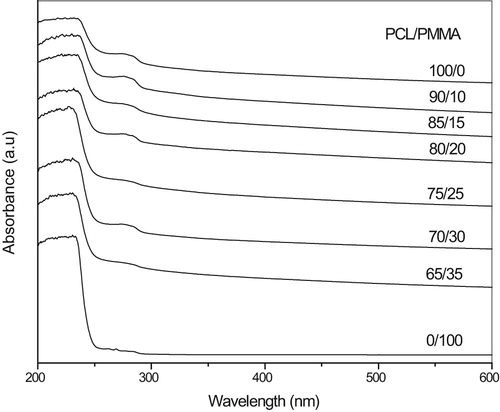

UV-Vis analysis of PCL/PMMA blend films is represented in Fig. 3. The spectra indicate an absorption band centered around 280 nm, which is characteristic of PCL and related to carbonyl groups (C=O) [Citation23]. This is confirmed in FTIR at about 1726 cm−1 band which is assigned to π-π* transition, and the sharp edge in the range of 245–270 nm, which is shifted toward the longer wavelength with increasing PCL concentration. The complexation between the PCL and PMMA can be indicated by these shifts. The present results show that no absorption peaks at longer wavelength >280 nm.

3.3.1 Measurement of the energy gap (Eg)

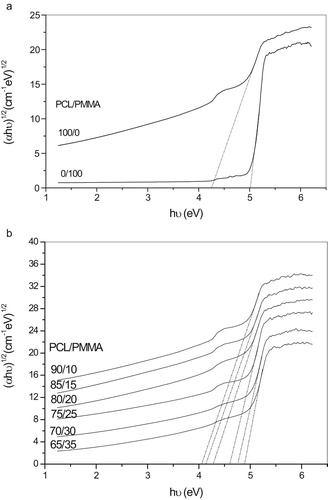

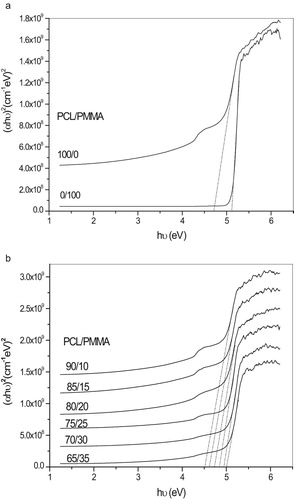

Absorption coefficient as a function of frequency α(υ) and the optical energy gap Eg obeys the classical Tauc's expression. Using UV-visible spectra, the optical energy gap is determined by translating the spectra into Tauc's plots. The frequency-dependent absorption coefficient is given by Devis and Mott formula [Citation24],(1)

(1) where h is Planck's constant, υ is the photon frequency, β is a constant related to the properties of the conduction and valence bands, and α is the absorption coefficient that can be determined as a function of photon frequency using the equation:

(2)

(2) where A is the absorbance, n is the exponent factor, d is the thickness of the sample and Eg is the energy gap between the bottom of the conduction band and the top of the valence band at the same value of wave number.

On the basis of Eq. Equation(1)(1)

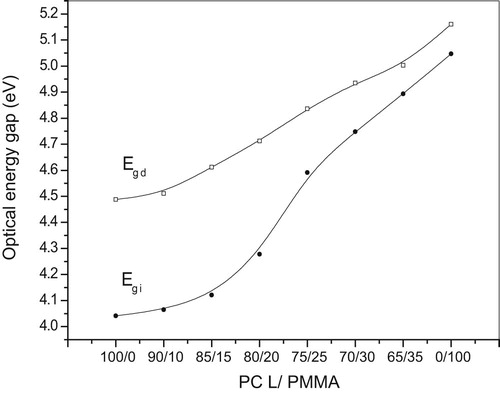

(1) , the value of n = 2 allowed for indirect transitions and 1/2 allowed for direct transitions of unpaired electrons. The relation of (αhυ)n versus the photon energy (hυ) shows a linear part behavior, which are presented in Figs. 4a, 4b, 5a and 5b. Each linear portion indicates an optical energy gap Eg. The values of Eg for both direct (Egd) and indirect (Egi) transition of free charges are listed in . In Fig. 6 and , it is remarkable that increasing PCL content leads to decreases in energy gap. This indicates that the PCL addition significantly influences energy gap by invoking the occurrence of local cross linking within the amorphous phase of PMMA and confirms the compatibility between the two biopolymer blends.

Table 3 Calculation of energy gap for both direct and indirect transition.

3.4 Thermal analysis

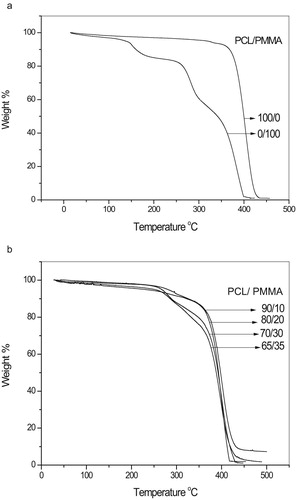

Fig. 7a,b displays thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) for pure PCL, pure PMMA and their blends with a heating rate of 10 °C/min ranging from room temperature 30–500 °C. From Fig. 7b, it is obvious that the samples started to lose their weight in the range of 50–70 °C due to the moisture evaporation and stabilize up to 120 °C, above which the solvent evaporated. For all the samples the major weight losses are observed in the range of 370–430 °C. This may be correspondent to the structural decomposition of the polymer blends. From Fig. 7a pure PMMA has three main transition regions: the first transition is due to evaporation of water and mono carbon oxide that occurs in the range of 30–145 °C, the second transition is due to the degradation of the polymer that occurs around 180–260 °C, the third transition is due to the cleavage of the backbone of the polymer that occurs above 300 °C and complete decomposition of the polymer that occurs nearly at about 400 °C, where as pure PCL started weight loss up to 369 °C and completely decomposed at nearly about 430 °C, so that PCL has a decomposition temperature higher than PMMA by nearly 30 °C [Citation25].

Thus it may be concluded that the addition of PCL to PMMA increases the thermal stability of the blend due to the incorporation of the PCL into the host PMMA.

4 Conclusion

In this work, PCL/PMMA biopolymer blends were prepared by a simple casting method. The results suggest that homogeneity is formed over all the biopolymer blend compositions. Various types of bands for the two biopolymers and their blends were assigned in FTIR spectra. XRD scans reveal broad and sharp peaks, which indicate the amorphous nature of PMMA and the semi-crystalline nature of PCL, respectively. From UV-Vis spectra, with increasing PCL concentration the position of the sharp edge was slightly shifted toward higher wavelength and also the energy gap decreased from 5.047 to 4.265 eV; this suggests the miscibility between the biopolymer blend. From TGA studies, it is clear that the weight loss of the PMMA is higher than the weight loss of the PCL. Thus, it may be concluded that the addition of PCL biopolymer increases thermal stability. All previously stated results suggested that the optimum concentration at PCL/PMMA 80/20 of the bioblends may be taken to improve some of the electrical, structural and optical properties for use in biological applications, such as drug delivery [Citation26], and this is the main purpose of this work.

References

- M.J.FolkesP.S.HopePolymer blends and alloys1993Chapman and HallLondon

- L.A.UtrackiPolymer alloys and blends1990HanserNew York

- I.S.ElashmawiN.A.HakeemE.M.AbdelrazekSpectroscopic and thermal studies of PS/PVAc blendsPhysica B403200835473552

- M.SivakumarR.SubadeviS.RajendranWuH.C.WuN.L.Compositional effect of PVdF-PEMA blend gel polymer electrolytes for lithium polymer batteriesEur Polym J43200744664473

- A.M.StephenS.KalyanasundaramA.GopalanN.MuniyandiN.G.RenganathanY.SaitoIonic conductivity and FT-IR studies on plasticized PVC/PMMA blend polymer electrolytesJ Power Sources720014452

- R.H.Y.SubbanA.K.ArofPlasticizer interactions with polymer and salt PVC–LiCF3SO3–DMF electrolytesEur Polym J40200418411847

- SunZ.WangW.FengZ.Criterion of polymer-polymer miscibility determined by viscometryEur Polym J28199212591261

- S.R.ChastainA.K.KunduS.DharJ.W.CalvertA.J.PutnamAdhesion of mesenchymal stem cells to polymer scaffolds occurs via distinct ECM ligands and controls their osteogenic differentiationJ Biomed Mater Res7820067385

- XinX.M.HussainMaoJ.J.Continuing differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells and induced chondrogenic and osteogenic in electrospun PLGA nano fiber scaffold lineagesBiomaterials282007316325

- A.P.ElfickPoly (epsilon-caprolactone) as a potential material for a temporary joint spacerBiomaterials23200244634467

- L.ShorS.GuceriWenX.M.GandhiSunW.Fabrication of three-dimensional polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite tissue scaffolds and osteoblast-scaffold interactions in vitroBiomaterials28200752915297

- ChenT.R.P.KusyEffect of methacrylic acid methyl methacrylate monomer ratios on polymerization rates and properties of polymethyl methacrylatesJ Biomed Mater Res361997190199

- J.JohnS.A.GangadharI.ShahFlexural strength of heat-polymerized polymethyl methacrylate denture resin reinforced with glass, aramid, or nylon fibersJ Prosthet Dent862001424427

- GuiY.L.XingP.Z.LiangC.XiaoY.Z.XiaoL.X.W.M.YiuElectrospun aligned PLLA/PCL/functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotube composite fibrous membranes and their bio/mechanical propertiesCompos Sci Technol722012248255

- ChenE.C.WuT.M.Isothermal crystallization kinetics and thermal behavior of poly (ε caprolactone)/multi-walled carbon nanotube compositesPolym Degrad Staby92200710091015

- PanW.ZhangH.ChenY.Electrical and mechanical properties of PMMA/nano-ATO compositesJ Mater Sci Technol252009247250

- S.KumarA.SharmaB.TripathiS.SrivastavaS.AgrawalM.Singhet alEnhancement of hydrogen gas permeability in electrically aligned MWCNT-PMMA composite membranesMicron412010909914

- PanL.PeiX.HeR.WanQ.WangJ.Multiwall carbon nanotubes/polycaprolactone composites for bone tissue engineering applicationColloids Surf B Biointerfaces932012226234

- S.RajendranT.UmaConductivity studies on PVC/PMMA polymer blend electrolyteMater Lett442000242247

- S.RajendranT.UmaLithium ion conduction in PVC-LiPF4 electrolytes gelled with PMMAJ Power Sources882000282285

- DuanG.ZhangC.LiA.YangX.LuL.WangX.Preparation and characterization of mesoporous zirconia made by using a poly (methyl methacrylate) templateNanoscale Res Lett32008118122

- A.ElzubairC.N.EliasJ.C.M.SuarezH.P.LopesM.V.P.VieiraThe physical characterization of a thermoplastic polymer for endodontic obturationJ Dent342006784789

- A.De CamposS.M.M.FranchettiBio treatment effects in films and blends of PVC/PCL previously treated with heatBraz Arch Biol Technol482005235243

- N.F.MottE.A.DavisElectronic process in non-crystalline material1979Clarendon PressOxford

- K.SaeedS.Y.ParkPreparation and properties of polycaprolactone/poly (butylene terephthalate) blendIran J Chem Chem Eng2920103

- H.W.KimJ.C.KnowlesH.E.KimHydroxyapatite/poly (e-caprolactone) composite coatings on hydroxyapatite porous bone scaffold for drug deliveryBiomaterials25200412791287