Highlights

| • | The study uses focus groups to explore European consumer perceptions of bio-based. | ||||

| • | Results indicate unfamiliarity with ‘bio-based’ in general and for specific products. | ||||

| • | Results show positive, negative and mixed affective associations with ‘ bio-based’. | ||||

| • | Results show more specific associations with ‘bio-based’ products than the concept. | ||||

| • | Findings suggest importance of coherent product characteristics for trustworthiness. | ||||

Abstract

This study explores people’s perceptions (i.e., positive and negative associations, mixed feelings) regarding the concept of ‘bio-based’ in general and specific bio-based products. This exploratory study is one of the first consumer studies in the field of bio-based research. Three focus group discussions were organized in the Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Italy, and The Netherlands (with 89 participants in total) in which projective techniques were applied.

Results of these group discussions indicate that participants are unfamiliar with ‘bio-based’ as a concept. ‘Bio-based’ is most often associated with positive environmental issues as “naturalness” and “environmental friendly” but also with negative environmental associations and to a lesser extent with technological and health issues. Associations with ‘bio-based’ as a general concept and with particular bio-based products can be simultaneously positive and negative, which caused uncertainty and mixed feelings by the respondents. This idea highlights both the complexity of and a lack of familiarity with the concept of ‘bio-based’. Consumers have a holistic perception of bio-based products, i.e., they combine their perception of different aspects of the product in an evaluation of the whole product concept (e.g., their perception of the original product, usability, production method, proportion of bio-based materials used, price, packaging material, and appearance). Discussions on ‘bio-based’ as a concept are more general and abstract, while discussions and associations related to bio-based products are more specific. This study’s qualitative approach illustrates in detail the great variety in consumers’ perceptions, which can be both cognitive and affective (including positive, negative and mixed feelings towards ‘bio-based’ as a concept as well as bio-based products).

1 Introduction

In an ideal bio-based future, we will find alternatives for non-renewable resources to create prosperity and progress that are in balance with the ecological limits of this planet. Bio-based production will make more widespread use of biomass to replace fossil-based resources. In a bio-based economy, biologically derived materials will replace synthetic materials, in the production of bio-based polymers or chemicals as well as in replacement of concrete with bamboo or hemp in construction [Citation6].

A transition towards such a bio-based economy must not only be technologically feasible and economically viable but also socially desirable (see Ref. [Citation15]: 17, 376). Consequently, this transition depends not only on the effort and enthusiasm of professionals and policymakers but also very much on the acceptance and involvement of consumers.

The importance of obtaining insight in ordinary people’s perceptions about new technologies right from the start can be illustrated by the case of genetic modification [Citation3,Citation11]. Although professionals see many benefits to genetic modification, this technology is not generally accepted and might even be rejected by consumers. Because the transition towards a bio-based society is still at an early stage and little is known about consumer perception of bio-based processes and products, it is important to investigate what types of images, expectations, or concerns consumers have.

However, not much is known about consumer perceptions and reactions regarding bio-based production processes and specific bio-based consumer products. Unfortunately, consumer-oriented research devoted to related issues is not very helpful. Although these studies consider food consumption or environmental friendliness, no direct link is made to bio-based issues. There are, for example, studies that concentrate on consumers’ willingness to buy organic food products [Citation12] and functional foods [Citation28] or to eat insects [Citation16,Citation35], consumers’ reactions to environmental packaging [Citation13,Citation26] and environmentally friendly transport [Citation19], or consumers’ acceptance of products made with new technologies such as genetically modified products [Citation3], nanotechnology [Citation27] or cultured meat [Citation36,Citation37].

From literature on the acceptance of new technology and food product development it is known that more general and more specific notions of bio-based need to be taken into account. For example, the general perspective of ‘bio-based’ is in accordance with a study of Verdurme et al. [Citation38] on consumer acceptance of new technology from a general perspective. This means that on a general level, ‘bio-based’ as a concept is represented as a process or as a technology. The specific level is, for example, presented in the study of Krystallis et al. [Citation14], who show that when providing consumers with a more realistic choice context or product, is a more relevant predictor for likelihood of success of products developed with the new technology. In the case of ‘bio-based’ this means, for example, the production of (partially) plant-based bottles. Therefore, for an in-depth exploration of consumers perception of the term ‘bio-based’, we must include a) a general level in which we explore whether individuals understand the term and what type of associations respondents have with this term and b) a product-specific level in which we guide consumers to consider specific bio-based products in order to explore perceptions, associations and feelings on a product-specific level.

In the current study, we therefore aim to provide a broad understanding of consumer perception of bio-based by distinguishing between ‘bio-based’ as a general concept and products that make use of bio-based materials. Additionally, in accordance with the definition of perceptions, we not only focus on cognitive aspects but also include affective aspects (i.e., feelings and emotions) in our analysis [Citation33]. For a newly-published study taking also but differently people's emotions into account with respect to the bio-based economy, see Ref. [Citation29]. Consequently, this study allows us to improve our understanding of the current level of awareness and acceptance of ‘bio-based’ as a general concept and more product-specific conceptions of ‘bio-based’ among contemporary Europeans.

1.1 Relevant literature

Directly related to bio-based topics are two studies that focus on consumer acceptance of bio-based packages [Citation2,Citation21]. A closer look at the studies shows that the first [Citation2] focuses on the quality perception of blueberries after storage in a bio-based package. That is, the main focus is not the bio-based packages but consumers’ answers to questions about the quality of the blueberries. The second study [Citation21] explores the technical quality of bio-based materials used for food packaging. This study does not include consumer perception of bio-based packages as such and therefore does not provide an in-depth analysis of consumer perceptions of bio-based products or processes.

In addition to these two studies, a recent study by Koenig-Lewis et al. [Citation13] focuses on consumers’ cognitive and affective responses to ecological packaging. Although Koenig-Lewis et al. do not explicitly focus on the concept of ‘bio-based’, the stimulus material they use in their study (i.e., a bottle made partly of plant-based material) can be viewed as an example of a bio-based product. One of the most relevant aspects of this study is that the authors find that emotions rather than rational evaluations are the key driver in the intention to purchase the plant-based bottle. This study thus provides evidence that consumers, when confronted with environmentally friendly purchase options, react not only rationally but also emotionally; this is something that may also be reflected in consumer reactions to bio-based products.

The results from one of the few preliminary explorations with a focus on bio-based processes and products that has been carried out thus far can be found in Industrial Biotechnology. This study of Walter [Citation39] presents a large survey among US and Canadian consumers that shows that most respondents have only a limited understanding of what makes household products environmentally friendly. Moreover, a minority of the respondents indicate that they recall hearing the term ‘bio-based’ to describe products or product ingredients. The most commonly mentioned bio-based products (unprompted) are fuel products (e.g., ethanol and biodiesel), cleaning products (e.g., detergents, soaps), fabric and clothing (e.g., lingerie, hemp, bamboo), and household and personal care products (e.g., paper products). Despite little familiarity with these products, respondents show a strong interest in purchasing such products when they are comparable to non-bio-based products in terms of price and benefits.

Other preliminary research that focuses on consumer attitudes towards bio-based products and processes includes two focus group studies in The Netherlands. Both studies show overlap in their findings: Tertium [Citation32] considers the general concept of ‘bio-based’, while the Athena study [Citation40] concentrates more specifically on bioplastics. These studies suggest that contemporary consumers do not have a clear notion of ‘bio-based’ as a concept and do not have much ready knowledge of bio-based plastics either. Furthermore, consumers display negative reactions, such as ‘expensive’ or ‘activistic’, as well as positive reactions, such as ‘green’, ‘organic’ or ‘progressive’. In summary, bio-based products and processes are, from a consumer perspective, still in their infancy. They are hardly an issue in the everyday life of ordinary consumers but are related to all sorts of associations and generate few ideas about behavioural consequences or personal commitments. Generally, such findings are corroborated in a survey study amongst Dutch citizens [Citation34].

The examples mentioned above confirm that, to date, research on consumer perceptions of bio-based processes and products is limited. Insights in consumer acceptance of bio-based is necessary in order to get insight if labelling of bio-based is needed and how this should be done. Consumer perception is therefore key, and our approach is to study consumer perception from the perspective of bio-based both as a general concept and specifically, from the perspective of several bio-based products. Below, we examine to what extent our focus groups (N = 89) in five European countries compare similarly or dissimilarly to the exploratory consumer studies mentioned above. Our study extends previous studies by conducting a large-scale qualitative study that explores how consumers perceive bio-based processes and products. Previous studies differ in the type of research or focus on one specific product alone. This study complements these findings by exploring how ‘bio-based’ is perceived in both a general and a product-specific manner and thus also compares different products.

In the following section, we present a detailed description of our methodological approach and the focus group discussions. Section 3 provides the results obtained from these focus groups, which are discussed and reflected upon methodologically in section 4. A short final section presents the conclusions of this paper.

2 Methods

2.1 Selection of participants

Fifteen focus groups were held in five European countries in four different regions: Germany and The Netherlands representing (i) Western Europe, Czech Republic representing (ii) Eastern/Central Europe, Denmark representing (iii) Scandinavia, and Italy, representing (iv) Southern Europe/Mediterranean. These countries were selected by their leading status in the field of environmentally friendly products (purchase of environmentally friendly products, purchase of energy efficient appliances, awareness of environmental impacts of products, awareness of sustainability labels) and within the field of biotechnology (support for biotechnology and genetically modified food) as described by Flash Eurobarometer number 256 [Citation7], the Eurobarometer 64.3 [Citation5] and the Special Eurobarometer 389 [Citation30]. For each focus group, at least 6 participants were invited.

The sample consists of a total of 89 participants: 52 were women; 75 participants were 20–59 years old, and 14 were over the age of 60; most of the participants were middle or higher educated; and 73 were employed. In total 30 users, 2 for each group, that participated were selected based on their interest in technology and their environmental awareness. They were selected in order to contribute to the discussion, with inspiring ideas. All participants met the following criteria: (1) Participants must not be illiterate and (2) Participants must not work in (a) the Petro-chemical industry, (b) the Energy sector, (c) the Cosmetic industry, (d) the Media, (e) Farming, or (f) Market research (bureaus), and (3) Participants must not have expertise or experience in the production of bio-based products. These criteria were selected because we aimed to explore the perceptions of consumers towards ‘bio-based’ and not the perceptions of people having more or specific knowledge or expertise about ‘bio-based’.

The participants of five European countries were used as one sample across analyses. We decided to report the findings across all countries because the results are generally similar across countries.

2.2 Procedure

The focus groups were conducted in 2014 in each of the five study countries. Interview time was about 120 min. A professional market research agency in each country recruited participants and conducted the group discussions following the same protocol in each country. The focus group interviews were of semi-structured nature and conducted according to a predetermined protocol common to all countries. In each country, moderators used the protocol (translated to every native language by the local agencies) to ensure consistency and uniformity of the process in all focus groups.

Since the study of consumer perception of bio-based processes and products is still in an exploratory phase, projective techniques were used. These techniques have shown to be very useful in consumer research, especially in those areas that people find difficult to talk about ([Citation8]; Webb, 1992). Gorden and Langmaid [Citation9] list five main types of projective techniques from which we selected two, namely, association and choice ordering procedures (i.e., application of a list of keywords and grouping tasks).

During the different parts of the focus group sessions a distinction has been made between consumers’ perceptions of ‘bio-based’ as a general concept and ‘bio-based’ as an embodied attribute of specific products. Consequently, we can compare ‘bio-based’ as a general concept with specific bio-based products, contributing to the development of and communication about bio-based products.

2.2.1 General level

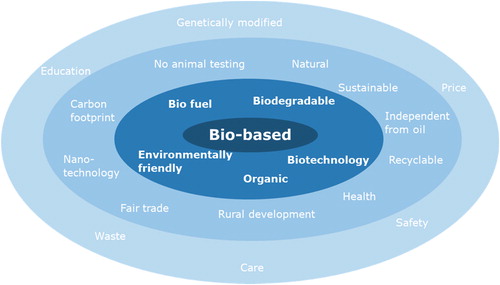

The first task was to gain insight into consumer perception of the term ‘bio-based’ by means of a word association exercise. We prepared a comprehensive list of terms that could play a role in thinking about ‘bio-based’ and presented it to the participants. The keywords were Environmentally friendly, Bio-based, Sustainable, Genetically modified, Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Biodegradable, Recyclable, Carbon footprint, Biofuel, Fair trade, Organic, No animal testing, Health, Safety, Natural, Price, Care, Education, Rural development, Waste, Independent from oil, and Blank cards (to be filled out by participants if they wanted to add a term). Participants were asked to perform several tasks (e.g., grouping keywords, selecting and ranking keywords).

2.2.2 Product-specific level

The second task was to gain insight into consumer perceptions of specific bio-based products. Seven products were selected based on the following criteria: (i) consumers must be able to buy and use the product, and (ii) the (potential) market volume of the product has to be substantial. Furthermore, the products should differ according to (a) the degree a consumer comes into physical contact with the product, (b) being a branded product or not, and (c) differ in the amount consumers are involved in purchasing products (e.g., fairly routine versus high risk or high cost purchases). The following products were selected: T-shirt, Foot cream, Shopping bag, Coca-Cola bottle, Door trimming/dashboard, WPC-decking, and Natural paint. Most of the products were available during the sessions, if not possible, pictures of the products were present. These products are used as examples that cover a broad range of specific products in order to explore perceptions towards bio-based products on a product-specific level. Thus, the focus is not on individual perceptions of these products but on differences and similarities across these products linked to the perception of ‘bio-based’.

Participants discussed their associations with and perceptions of these 7 products. For participants to become familiar with the different products and to gain insight into the differences and similarities of these products, the second exercise started with a grouping task of all seven products (ordering task; [Citation9]). Next, all products were discussed individually in detail. Participants were asked about their associations with the specific products and their feelings towards them.

2.3 Analyses

Atlas.ti version 7 was used to analyse the translated transcripts. Transcripts were coded by three independent coders. According to standard content analysis procedures [Citation18], transcripts were coded into themes by looking for common associations, perceptions and feelings across the focus groups. Later on in the process, themes that appeared to convey the same meaning were merged. Output lists and co-occurrence tables were used to answer the research questions.Footnote1 The interpretation of the results was performed by three independent researchers.

3 Results

3.1 General level: linkage of keywords with the concept of ‘bio-based’

Participants received 21 keywords to explore which words they would link to the term ‘bio-based’. The results showed that participants linked all provided keywords to ‘bio-based’, but some keywords were mentioned more often than others. For example Biodegradable was mentioned 29 times and Waste 8 times. presents which keywords are most often (closest to the centre) or least often (farthest away from the centre) chosen when grouping all the key terms.

For some participants, this was a difficult task because they were not familiar with some of the keywords in general or the specific term ‘bio-based’. These respondents grouped ‘bio-based’ together with other terms they were not familiar with. For example, they mentioned that ‘bio-based’ is a popular word that is not properly understood by the public. Another solution chosen by participants was to group ‘bio-based’ with other keywords that include ‘bio’, such as Biotechnology, Biodegradable, and Biofuel. The term bio-based was also grouped with keywords that relate to the environment, such as Organic, Environmentally friendly, Natural and Sustainable.

Participants often used environment-related associations to group the term bio-based, such as the reduction of waste, fossil fuels or sustainability. Another perspective used to group the keywords was related to products and product characteristics or product life cycles, such as associations with shopping, cosmetics, or food. Another group of participants made the association between ‘bio-based’ and the development of new technologies or innovation. In this case, bio-based was viewed as a novel technique or method that could be used for various purposes in the future, such as a new source of energy. There was also a range of other associations that were used less often to group the term ‘bio-based’, for example, safety for humans, ways for ‘bio-based’ to relate to human or social life, and ‘bio-based’ being an English term.

“Then I have a second group, the biggest one and this is called ‘Day-to-Day Life and Cosmetics’. This one includes safety, natural, environmentally friendly, bio, that is to say bio-based, health and no animal testing. This goes a bit in the direction of foodstuffs and cosmetics that you use on a daily basis. (DE group 2 #5)”

“I have also words [including bio-based] related to energy and the future in the same group. (DK group 1 #2)”;

“The second group was development and science, that’s where I placed bio-based. […] When we run out of fossil fuels, we’d have to look for alternatives in order to produce plastic. You can do that with bio plastic. (NL group 3 #2)”.

Participants had positive, negative and mixed feelings towards bio-based. To clarify how these feelings occur we explored which themes (i.e. related associations) respondents mention. Positive feelings in combination with bio-based were mentioned in combination with good for the environment or natural, healthy, or energy-related and innovative. Negative feelings with bio-based were expressed when they were not familiar with the term or perceived the term as a marketing trick. There were also mixed feelings related to bio-based. These feelings occurred when respondents asked themselves whether bio-based is truly innovative, good for the environment or healthy. These questions included a certain degree of distrust, e.g., bio-based as a term that is used to hide something. Some participants questioned whether certain characteristics are a part of bio-based products, whereas others mentioned they did not trust bio-based products to have specific characteristics (e.g., sustainable, biodegradable). It should be noted that the various categories of associations are not mutually exclusive. Participants often mentioned multiple associations at the same time. For an overview of the themes mentioned in combination with positive, negative and mixed feelings, see .

“The profaned, tricky terms [including bio-based] that serve to eco-terrorism and make some tricksters richer, the Ministry of Finance, etc. (CZ group 2 #5)”;

“It is a negative group where they only care about the price. I thought of Lidl and the like. And bio-based got in that group because it is a silly word, because everything is bio-based. I mean we live in this world and everything is bio-based. I think the term is silly and wants to hide something.” (DE group 1 #1)

Table 1 Feelings towards ‘bio-based’ and related associations.

3.1.1 Questions raised about the term ‘bio-based’

The results show that many participants were not familiar with the term bio-based. shows an overview of the questions that participants posed during the discussions. The words ‘bio’ and ‘based’ raised several questions, but we also observed assumptions that these products are partially bio-based or organic. In addition, participants wondered how environmentally friendly bio-based products are and whether the term ‘bio-based’ applies to a product or a production technique. Some participants wondered whether ‘bio-based’ implied being biodegradable, whether it is a form of energy or if energy could be produced in a bio-based manner, or whether ‘bio-based’ implies waste reduction. In this sample, only a minority knew that the concept ‘bio-based’ has something to do with renewable resources rather than fossil fuels. Such a lack of knowledge can evoke negative feelings and feelings of distrust. Other participants seemed to find the word ‘bio-based’ deceiving because it is not completely biological. In short, there was much confusion regarding the term and its environmental impact.

“It [bio-based] is a very strange word. What does it mean? (DK group 1 #5)”;

“Bio-based, carbon footprint, nanotechnology, genetically modified, biotechnology, bio fuel, independent form oil − i.e. words that are commonly used, but their accurate meaning is probably known only by experts, i.e. lab geeks, technical terms. (IT group 1 #5)”.

“It doesn’t tell me exactly what it is about. Perhaps it started out as something good, then it has taken a turn. Somehow, I have the feeling that it is a trap. (DK group 2 #5)”

Table 2 Questions of participants about ‘bio-based’.

3.2 Product-specific level: associations with seven bio-based products

During discussion on the seven specific products, a wide range of associations were addressed, including positive, negative and mixed feelings.

3.2.1 Positive associations

When discussing the products individually, participants can be positive about the aesthetics and exterior characteristics. For example, participants liked the shape of the T-shirt, shopping bag and WPC-decking. Positive feelings towards T-shirts were related to health aspects such as being able to avoid allergies. Participants were also positive about the natural and environmentally friendly aspects of the T-shirt and foot cream. People mentioned that the naturalness gives them a good feeling. They use this cream on their own body, and therefore, they believe that the natural content is important for their health. Health aspects are often mentioned in relation to the absence of toxic substances. In relation to the shopping bag, the idea of a natural bag is viewed as a development in the right direction. Participants refer to the environmental friendliness and degradability of the bag, which they associate with a positive feeling. For the dashboard, people like the idea that part of the car is produced in a more environmentally friendly way by using fewer chemicals. For WPC-decking the environmental friendliness is linked to durability. The idea that the WPC-decking is made from renewable materials is mentioned as having a positive association. A group of the participants believed that these tiles might be less expensive than regular or wooden tiles. For these participants, the low price would be a reason to buy the WPC-decking. Participants linked natural paint to the environment and thought of it as better than regular paint because it is less toxic and better for one’s own health and that of the children. Participants thought of the natural paint as an organic paint, which is produced more naturally and environment friendly than regular paint is.

Although most participants refer to ‘bio-based’ and naturalness as a positive aspect, they also note that in choosing products, for most participants, ‘bio-based’ is not a decisive element on its own. First and foremost, a T-shirt should look nice. This was also the case for the dashboard. A group of participants stated that they do not think the bio-based production of the dashboard is a decisive element: the price of the products is also an issue. However, if the functionality is the same and the price of bio-based products is the same or lower, participants become more interested. Nevertheless, there are also participants willing to pay more for the dashboard and for the natural paint.

“Naturalness, that you have something on your body that is natural and that has not been produced chemically but that has been made of plants. That gives you a good feeling and sooths your conscience (DE group 2 #5)”;

“very well, from recycled material, which is good, that’s why I separate my plastic waste. This is made from recycled material, no other resources (NL group 1 #3)”;

“maybe, it lasts longer than wood, I would believe it (CZ group 3 #6)”,

“I think it is a product that you only have for a short time. It belongs to the use and throw away-products. So it is a good thing that they have done something about the material (DK group 1 #2)”,

“It's just as good as any other paint, but it's not polluting. Paints are among the most polluting products, by the way. I just assume plant-based oils are less polluting (IT group 2 #1)”.

3.2.2 Negative associations

In addition to positive associations, negative associations were also reported. Some participants did not like the T-shirt, WPC decking or dashboard because it did not suit their taste. Another barrier for buying the T-shirt was durability. This concern was also raised for the natural paint because some worried about its durability and coverage. Price was also mentioned as a barrier. Bio-based products such as the T-shirt, dashboard and natural paint are more expensive than regular products. In addition, there are also negative associations related to distrust. For example, some participants distrusted that the production process took place in China. That participants are more positive towards coherent products, of which packaging, production and composition are in line with each other, was also indicated during discussion about the foot cream. Participants did not like the packaging of the product, although they did like the content and the natural character of the cream. In addition to these doubts, participants raised concerns about the convenience of particular products, e.g., the size of the shopping bag, and whether the bag would be as strong as a regular bag. Paint seemed to be a product that is difficult to match with naturalness; the dangers of toxicity were brought up. People were sceptical about the levels of chemicals and toxins used for the production of this paint. Not only paint but also WPC-decking is linked to the use of chemicals in production. Indeed, the WPC-decking raised many questions concerning distrust and a lack of clarity.

When discussions became more detailed, issues such as biodegradability were raised. Some participants disliked the shopping bag for being biodegradable. They wanted a bag that lasts and does not dissolve when things are being stored inside it. Others liked the bag because it was biodegradable. Thus, the same characteristic was perceived as both positive and negative by different groups of respondents. Another issue was the impact of the different products. For example, what is the percentage of bio-based components? Due to the low percentage of bio-based materials in the soft drink bottle, there were many questions regarding the true motive of the company. Some consider it a win–win situation. However, other participants questioned whether bio-based materials were included for environmental motives or only for profits, i.e., that the bottle is used for greenwashing. Moreover, both the bottle and the dashboard were considered from a similar perspective, namely, as a marketing stunt or sales trick or a way of greenwashing while making additional profits.

“Not necessarily. It depends of the difference in price. But if I plan to live in my house for at least 10 years, it might be a possibility. But there are several things to consider (DK group 3 #5)”,

“It is a clothing item, and everyone needs the clothing, it is from hemp, I read it was made in China, which took me aback, once again carbon footprint, then that there are the terms and conditions created for those who make it, so it is positive but this carbon footprint and that it is not made in our country, companies should employ people here and not in China (CZ group 3 #3)”.

“I think that it is a very thin shopping bag. I usually use a shopping bag several times. I’m not sure that this shopping bag can stand up to that. I think that it will break faster than an ordinary shopping bag (DK group 1 #4)”.

“But it's still 80% not bio-based. Is this better degradable or not? It's only a small share that is bio. It should be more (DE group 2#2:)”,

“a marketing gimmick, competition among car manufacturers is fierce, so they must come up with something, this might be one of the way to impact and win the customer, always you should look at what the manufacturing causes, whether it is not far worse than the production of the leather or aluminium that burdens the environment subsequently when we chuck it (CZ group 2 #2)”,

3.2.3 Mixed feelings

The paragraphs above show that associations related to price and the environment are considered both positive and negative. Some participants liked the design or that the product is partially made with plant-based materials, while others did not like it, e.g., the product too closely resembled plastic. This finding indicates that some bio-based products, in the perception of some consumers, cannot or should not resemble plastic. There was also uncertainty regarding one’s own feelings. Participants indicated for example that they feel natural products should be healthier but that they are unsure if this claim is true. In addition, if certain issues are not clear to participants, they feel ambivalent. Examples of this are participants’ feelings towards the shopping bag and its degradation, or the WPC-decking and its relation to wooden tiles. Some participants stated that they would only use the tiles if the WPC-decking was less expensive or at least not considerably more expensive. Price was also mentioned as a barrier for buying natural paint. However, a different group of participants was willing to pay more for natural rather than regular paint. In addition, there were mixed feelings and distrust as a result of the warnings on the paint’s packaging. These warnings raised questions whether the paint was really natural. In line with this reasoning, participants also wondered whether being labelled as ‘bio-based’ is always positive in every aspect (regarding healthiness, toxicity, and environmental friendliness). These mixed feelings can be understood to highlight the need for more product information regarding, for example, the production and functionality of the product. Moreover, participants underscored the importance of a product’s coherence.

“I think biological plastic is a contradiction in itself. I just don't believe it. You would have to explain in detail why it is biological plastic (DE group 1 #2)”.

“I would think that it would be healthier for your body when you use natural products on your body. It should but I don’t know if that's true” (DE group 2 #6).

“Once again, it is about quality and price. When it is about paint, it is always a question of coverage. Therefore, if the quality and price were the same, I would probably choose it (DK group 1 #4)”.

“It is not good. It says that on one hand, it is produced from essential oils, and on the other that children shouldn’t come close to it. That information is enough for me not to use it. I prefer using water-based paint (DK group 1 #6)”,

3.2.4 Comparisons across products

shows the associations most often mentioned in regards to positive, negative, and mixed feelings across each of the seven products. As noted, we do not focus on specific products but on similarities and differences across products to explore how the concept of ‘bio-based’ is perceived at a product-specific level.

Table 3 Most common product-specific positive and negative associations and mixed feelings.

Compared to the general level, there was (on the product-specific level) more emphasis on the naturalness of bio-based products rather than their innovative or technical character. Participants mainly referred to environmental friendliness and naturalness and were generally positive about the use of more natural production methods. Participants thus seem to link bio-based products to a range of natural and pro-environmental aspects.

There were differences between products in regard to what extent they were perceived as environmentally friendly. The results imply that certain participants were more positive towards bio-based products that are 100% bio-based than towards products that were only partly plant-based. For example, some participants were more positive towards the shopping bag and the T-shirt compared to the Coca-Cola bottle and the natural paint because they judged these products on their proportion of environmental friendliness. People thus used this proportion as a criterion to group and evaluate these products. The partially plant-based products were more often associated with negative terms such as environmentally unfriendly or toxic, distrust, and marketing tricks of large companies. This finding implies that the proportion of ‘bio-based’ can be too small.

A match between the use of ‘bio-based’ and all other aspects of a product is important. There is a group of participants that preferred to have a coherent story. They did not like inconsistencies in the product’s image. It appears that a clear story is necessary to take away all doubts and mixed feelings among participants. This finding is shown to be relevant to all specific products, though it is manifested differently for each of them. For example, participants were sceptical of the T-shirt because the dye was too bright and therefore probably not natural. Moreover, it was produced in China, which does not fit well with the image of a ‘good product’ because China is far away and has a dubious relationship with human rights. The Coca-Cola bottle was also questioned, because it is only partly plant-based and because the use of plastic bottles is not environmentally friendly. The dashboard raised doubts because it is only a small part of a car, and driving a car is not environmentally friendly at all. The natural paint was questioned because of the warnings about its toxicity that say that one should not breathe the paint. All these products are questioned, and even distrusted, because their bio-based production does not match the broader context.

A related finding refers to the importance that a specific group of individuals attaches to the internal versus external (greenwashing) motivation of companies to make bio-based products. The perception that bio-based production methods are only used as a way to increase profits results in a negative association with companies. Furthermore, respondents seem to relate the proportion of bio-based materials to the effort that companies have made to produce a product in an environmentally friendly manner. As a result, small percentages of bio-based materials are linked to low efforts and external motivations and are therefore more often viewed as ‘marketing tricks’.

3.2.5 Questions raised about bio-based products

Again, the results show that the definition of ‘bio-based’ was not clear to participants. There was confusion and several questions were raised about the exact definition of ‘bio-based’ in relation to the specific products (see ). For example, there were questions regarding biodegradability, production process, content and percentage of bio-based materials used. Participants wanted to know what bio-based products look like and what percentage of a product should be bio-based in order to claim to be a bio-based product. Others asked what the characteristics of bio-based products are in general. Furthermore, participants asked for information regarding the production of bio-based products. Some also wondered whether the plants to produce the bio-based materials are grown specifically for this purpose or if these plants could have been used as food for people in need. Moreover, participants posed questions about the environmental friendliness of bio-based products. Participants discussing the seven specific products indicated that they missed specific information or asked for additional product information. It is likely that these questions result from participants’ unfamiliarity with the term ‘bio-based’.

Table 4 Examples of questions from participants regarding bio-based products.

4 Conclusion and discussion

This exploratory study on consumer perceptions regarding bio-based products in 5 European countries shows the following main conclusions. First, there is a lack of familiarity with bio-based products. Based on our sample, a large group of consumers indicated having questions, feeling uncertain, and having mixed feelings regarding bio-based processes and products. Second, associations with ‘bio-based’ as a concept and as a product can be positive or negative, or both at the same time. This idea highlights the complexity and uncertainty of consumer perception of the concept of ‘bio-based’. Third, the concept of ‘bio-based’ is most often associated with environmental issues and to a lesser extent with technical and health issues. Fourth, the discussion on ‘bio-based’ as a concept is very general and differs from the importance of personal use in consumers’ evaluations of ‘bio-based’ from a product-specific perspective. Consumer perception of bio-based products seems to be dependent on the concept and its entire context. Consumers combine the characteristics relevant to them, e.g., perception of original product, usability, production method, and proportion of bio-based materials. In the following paragraphs, we will further elaborate on the issues pertaining to each of these conclusions.

4.1 Unfamiliarity

Consumers participating in this study claimed being unfamiliar with the concept of ‘bio-based’ and bio-based products. This finding is in line with earlier qualitative research in The Netherlands [Citation32]. These questions ranged from the concept of ‘bio-based’ itself to the extent in which ‘bio-based’ is organic or environmentally friendly, to very specific questions related to the composition, production and waste of bio-based products.

4.2 Bio-based as an additional value

There are some clear overarching findings to discuss with regard to associations with bio-based products. In general, bio-based attributes are not a decisive characteristic on its own for buying or trying a product. Being ‘bio-based’ can be regarded as an additional value, while other aspects (e.g., convenience, looks and price) are more important and must be fulfilled before participants are willing to choose these specific bio-based products. This was similar to the findings of a focus group with consumers conducted in Austria about bio-based composites including also decking and automobile interior parts [Citation10]. The study indicated that the marketing communication of bio-based products should focus on specific product benefits as such and not only on the environmental benefits.

4.3 Personal benefits of bio-based

Consumer perceptions of bio-based products depend mainly on the answer to the question “what’s in it for me?” and less on the perceived benefits of bio-based production methods. The perception of specific bio-based products is based on the concrete context of the specific product in daily life. In this case, personal benefits become more relevant for the perception of ‘bio-based’. Additionally, the environmental friendliness and healthiness of bio-based products do relate to personal benefits, such as feeling good, or personal motives, such as having a sustainable and healthy lifestyle. Our findings underline that once consumers are confronted with a real product that contains a new technology, they tend to switch from a general mode of acceptance or rejection of a technology to a more differentiated mode in which the technology is assessed in the context of personal benefits [Citation1]. As a consequence, consumer adoption of a new technology and subsequent market growth through the communication of the benefits of a technology is generally hard to achieve [Citation22]. Instead, Phillips and Corkindale suggest that the acceptance of new technologies may be more successful if consumer evaluations were directly prompted by personal and relevant benefits already present in the product. Stated differently, people will buy what they see, need, and regard as beneficial [Citation22]; p. 117). Thus it is important for communication about bio-based to be as context-specific and concrete as possible.

4.4 Positive, negative and mixed feelings

Confronting consumers with the concept of ‘bio-based’ as well as a range of specific bio-based products evokes positive, negative and mixed feelings. Positive feelings are related to environment friendly topics. Negative feelings are related to technological topics. This can be explained by the ‘appeal to nature’ argument, which claims that anything natural is inherently good (or any other positive quality), whereas anything artificial or unnatural is inherently bad (or any other negative quality) [Citation17]. Research in various subareas has indeed shown that people prefer natural products over products made by human intervention [Citation25] and that products made with technologies that are perceived as more natural are more likely to be accepted [Citation31].

Besides positive and negative feelings, there were also mixed feelings. Positive feelings were combined with worries. This finding might indicate ambivalence [Citation24], indicating that individuals experience both negative and positive evaluations regarding the same concept.

4.5 Full versus partial bio-based products

The results imply that some participants differentiate between full versus partial bio-based. Consumers seem more positive towards bio-based products that use 100% bio-based materials compared to products that are only partially plant based. The partially plant-based products (‘hybrid’ products) were more often associated with negative terms such as environmentally unfriendly or even toxic, distrust, and marketing tricks of large companies. Additionally, participants seem to differentiate between internal versus external (greenwashing) motivations of companies to produce bio-based products. Small percentages of bio-based materials in products are sometimes perceived to be externally motivated; “bio-based production methods are only used as a way to increase profits”. Thus, the proportion of bio-based material can also be too small. This poses a serious risk because consumer scepticism towards firms that take opportunistic advantage of sustainable development trends is growing [Citation23,Citation4]. Greenwashing may be detrimental for the evaluation of a company, even for companies that truly aim to be responsible [Citation20].

4.6 Coherent product concepts

The results highlight the importance of a coherent product concept. Participants do not like inconsistencies in a product’s image. Products are questioned, distrusted, and related to negative associations when bio-based production does not match the broader picture. This finding indicates that one might question whether all products or elements of products are suitable to be marketed as a bio-based product. In any case, producers should show that they did everything they could to make this product as natural as possible. This involves all aspects of the production process because consumers seem to use all available information to evaluate the product. For example, there were negative associations with the content, packaging, production method, country of production (e.g., China was associated by some participants with dubious human rights) and transport. Note that this finding is based on the assumption by participants that bio-based production methods are aimed at finding pro-environmental or natural solutions. The association with bio-based products as innovative products or technologies necessary to adapt to a changing world was made less clearly by participants. Thus, participants linked bio-based products to naturalness. This linking has advantages in terms of positive associations with environmental friendliness. It also has disadvantages: participants have high expectations regarding the environmental friendliness of the total production process.

5 Suggestions for future research

In this qualitative research, projective techniques were applied. Although providing keywords might have steered participants in a specific direction, the wide variety of the keywords shows that ‘bio-based’ is associated with a broad range of terms. Additionally, the results show that participants use a variety of characteristics to group the seven bio-based product examples. All these characteristics are relevant to consumers when judging a product and thus might also be relevant for the development of bio-based products. At the moment, ‘bio-based’ is not a very familiar concept among consumers, which makes the provision of keywords for our task understandable. Future research might further explore perceptions and associations of bio-based products without guiding respondents with keywords. Such an approach would be useful in showing the spontaneous associations of respondents rather than prompted associations.

Note that the number of products discussed was large. It was therefore not possible to discuss each product in detail. Moreover, the character of the products was quite different with regard to the selection criteria, e.g., brand. As a result, the product-specific findings should be interpreted with care. The products are selected to provide an overview of how the concept of ‘bio-based’ can be applied to a range of products. These single products cannot be viewed as a good representation of a single type of product or product category. We therefore combine the findings of these products and use similarities and differences to draw conclusions across all products. The majority of the participants expressed a low involvement with most of the products. Further research is needed to explore the role of consumers’ perception and involvement in bio-based products.

The results show a variety of associations in each of the countries. Whether these countries differ in the number of people having these perceptions should be tested in future (survey) studies.

A transition towards a bio-based society needs such a consumer-oriented approach considering that its success depends not only on technological feasibility and economic viability but also on social desirability.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. KBBE/FP7EN/613677. The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Communities. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein

Acknowledgements

LEI Wageningen UR would like to thank, the moderators of the focus groups and the participants who discussed about bio-based products. We also would like to thank the companies that have send samples/products for the focus groups: Daniel Kruse (Hempro International) for the hemp-based T-shirt, Francesco Degli Innocenti (Novamont) for their bio-based shopping bag, Michael Atzmüller (Werzalit) for a sample of WPC-decking, and company Rolsma for the printed label of their natural paints. Finally, we are grateful for the comments and the constructive help in the execution of the work from our partners in work package 9 of the EU-project Open-bio: Martin Behrens (Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe, FNR), John Vos (BTG Biomass Technology Group), Lara Dammer (nova-Institut GmbH).

Notes

1 These documents are available upon request.

References

- P.AerniJ.ScholdererD.ErmenHow would Swiss consumers decide if they had freedom of choice? Evidence from a field study with organic, conventional and GM corn breadFood Policy3662011830838

- E.AlmenarH.SamsudinR.AurasJ.HarteConsumer acceptance of fresh blueberries in bio-based packagesJ. Sci. Food Agric.907201011211128

- M.Costa-FontJ.M.GilW.B.TraillConsumer acceptance, valuation of and attitudes towards genetically modified food: review and implications for food policyFood Policy332200899111

- S.DuC.B.BhattacharyaS.SenMaximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communicationInt. J. Manage. Rev.1212010819

- Eurobarometer 64.3, Europeans and Biotechnologie in 2005: Patterns and Trends, (2006)

- B.EricksonThe biobased economy at a crossroad: 15 years of progress and next stepsInd. Biotechnol.112015143145

- Flash Eurobarometer 256, Europeans’ attitudes towards the issue of sustainable consumption and production, (2009)

- M.GoodyearQualitative researchC.McDonaldP.G.vanEsomar Handbook of Market and Opinion1998EsomarAmsterdam177240

- W.GordenR.LangmaidQualitative Market Research: A Practioner's and Buyer's Guide1988Gower

- A.HaiderA.EderL.SobczakG.GrestenbergerMarket opportunities for bio-based compositesBiobased Materials—9th WPC, Natural Fibre and Other Innovative Composites Congress and Exhibition, June 19–20, 20122012

- T.Horlick-JonesJ.WallsG.RoweN.PidgeonW.PoortingaG.MurdockThe GM Debate: Risk, Politics and Public Engagement2007RoutledgeLondon

- I.KihlbergE.RisvikConsumers of organic foods—value segments and liking of breadFood Qual. Preference1832007471481

- N.Koenig-LewisA.PalmerJ.DermodyA.UrbyeConsumers' evaluations of ecological packaging—rational and emotional approachesJ. Environ. Psychol.37201494105

- A.KrystallisM.LinardakisS.MamalisUsefulness of the discrete choice methodology for marketing decision-making in new product development: an example from the European functional foods marketAgribusiness2612010100121

- H.LangeveldJ.SandersM.MeeusenThe Bio-based Economy: Biofuels, Materials and Chemicals in the Post-oil Era2012EarthscanLondon

- H.LooyF.V.DunkelJ.R.WoodHow then shall we eat?: Insect-eating attitudes and sustainable foodwaysAgric. Hum. Values312014131141

- G.E.MoorePrincipia Ethica (reprinted)1903Prometheus BooksUK(reprinted in 1994)

- D.L.MorganFocus groups as qualitative research2nd editionQualitative Research Methods Series vol. 16 (1997) Sage. London.

- R.OzakiK.SevastyanovaGoing hybrid: an analysis of consumer purchase motivationsEnergy Policy395201122172227

- B.ParguelF.Benoît-MoreauF.LarceneuxHow sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: a closer look at ethical corporate communicationJ. Bus. Ethics10220111528

- K.PetersenP.Væggemose NielsenG.BertelsenM.LawtherM.B.OlsenN.H.NilssonG.MortensenPotential of bio-based materials for food packagingTrends Food Sci. Technol.10219995268

- P.W.B.PhillipsD.CorkindaleMarketing GM foods: the way forwardAgBioForum532002113121

- A.PomeringL.W.JohnsonAdvertising corporate social responsibility initiatives to communicate corporate image: inhibiting scepticism to enhance persuasionCorp. Commun. Int. J.1442009420–439

- J.R.PriesterR.E.PettyThe gradual threshold model of ambivalence: relating the positive and negative bases of attitudes to subjective ambivalenceJ. Pers. Soc. Psychol.7131996431

- P.RozinM.SprancaZ.KriegerR.NeuhausD.SurilloA.SwerdlinK.WoodPreference for natural: instrumental and ideational/moral motivations, and the contrast between foods and medicinesAppetite432004147154

- C.H.SchwepkerJr.T.B.CornwellAn examination of ecologically concerned consumers and their intention to purchase ecologically packaged productsJ. Public Policy Mark.199177101

- M.SiegristN.StampfliH.KastenholzC.KellerPerceived risks and perceived benefits of different nanotechnology foods and nanotechnology food packagingAppetite5122008283290

- I.SiroE.KapolnaB.KapolnaA.LugasiFunctional food. Product development, marketing and consumer acceptance—a reviewAppetite5132008456467

- S.SleenhoffEmotions Matter for Public Engagement in the Emerging Bio-based EconomyPhD-thesis2016Delft University of Technology

- Special Eurobarometer 389, Europeans' attitude towards food security, food quality and the countryside, (2012).

- P.TenbültN.K.de VriesE.DreezensC.MartijnPerceived naturalness and acceptance of genetically modified foodAppetite4520054750

- TertiumBurgers over the Bio-based Economy [Citizens About the Bio-based Economy]2013TertiumAmsterdam

- H.Van TrijpM.MeulenbergMarketing and consumer behaviour with respect to foodsH.L.MeiselmannH.J.H.M.FieFood Choice, Acceptance and Consumption1996Blackie Academic & ProfessionalLonden264292

- VeldkampPublieksonderzoek Biobased Economy: Kennis, Houding En Gedrag [Survey Bio-based Economy]2013Bureau VeldkampAmsterdam

- W.VerbekeProfiling consumers who are ready to adopt insects as a meat substitute in a Western societyFood Qual. Preference392015147155

- W.VerbekeP.SansE.J.Van LooChallenges and prospects for consumer acceptance of cultured meatJ. Integr. Agric.1422015285294

- W.VerbekeA.MarcuP.RutsaertR.GasparB.SeibtD.FletcherJ.Barnett‘Would you eat cultured meat?’: Consumers’ reactions and attitude formation in Belgium, Portugal and the United KingdomMeat Sci.10220154958

- A.VerdurmeJ.ViaeneX.GellynckConsumer acceptance of GM food: a basis for segmentationInt. J. Biotechnol.5120035875

- F.J.WalterSeeking consumers for industrial biotechnologyInd. Biotechnol.732011190191

- D.LynchFocus Groups on Bio-based Economy2014Athena VU UniversityAmsterdam(unpublished manuscript)