Abstract

Climate variability has consequences on water availability in rice farming systems. In Ghana, rice farmers in the Northern Savannah are amongst the most vulnerable to long periods of drought and erratic rainfall conditions. Within the Kumbungu district, farmers engaged in both rain-fed and irrigated rice farming are no exception. Coping with uncertain water availability conditions requires adaptive decision-making for sustained productivity in rice cropping. From an adaptive governance perspective, the extent to which formal and traditional governance arrangements enable adaptive decisions amongst rice farmers remains a key question. Using an exploratory research design, the study investigates three key questions; what water-dependent decisions rice farmers take and how these are adaptive to changing water availability conditions; what formal and informal governance arrangements rice cropping decisions are embedded in; and how existing governance arrangements enable or constrain adaptive decision-making. Rice farmers in twelve communities around the Bontanga Irrigation Scheme in the Kumbungu District in the Northern region were engaged through individual interviews and focus group discussions. The study reveals that farmers take six major water-dependent decisions throughout the cropping season; decision to or not to plant rice, land preparation, planting, weed control, fertilizer application and harvesting. Farmer decisions are most adaptive to water availability conditions during planting and fertilizer application. Both formal and traditional governance arrangements influence the extent to which farmers are able to adapt to changes in water availability conditions. The paper also reflects on the potential of hydro-climatic information and the place of Environmental Virtual Observatories (EVOs) in adaptive governance and decision-making.

1 Introduction

Climate variability has significant impact on food systems especially in developing countries posing challenges in decision-making due to fluctuations in temperature and precipitation levels (CitationPietrapertosa et al., 2017; CitationChaffin et al., 2016; CitationBhave et al., 2016; CitationBuhaug et al., 2015). In Northern Ghana, meeting water needs in rice production remains a major challenge amongst rice farmers. This is attributable to highly variable and often unfavourable climatic conditions, dry spells and a mix of technical deficiencies of know-how, farm machinery and institutional inefficiencies in both irrigated and rain-fed rice farming systems (CitationAdongo et al., 2015; CitationKranjac-Berisavljevic et al., 2003). The Northern region has a single farming window typical of the Savannah belt in Ghana (CitationBawayelaazaa Nyuor et al., 2016; CitationYaro et al., 2015). Model projections suggest worsening climatic conditions with anticipated adverse impact on water availability (CitationAsante and Amuakwa-Mensah, 2014; CitationYaro, 2013; CitationLaube et al., 2012; CitationQuaye, 2008) and land degradation amongst others.

Interventions by government and private actors have sought to improve water availability conditions. This has come with infrastructure development and the mechanization of farming. Such infrastructure include irrigation schemes constructed to support small scale farmers who currently dominate farming systems in Northern Ghana. The Bontanga Irrigation Scheme in the Kumbungu district, North-East of the city of Tamale, is one of such schemes constructed by government in Northern Ghana. The scheme being the largest in northern Ghana covers a land area of 570 ha and gravitationally distributes water unto farmlands within the scheme (CitationBraimah et al., 2014). The scheme serves about 14 immediate communities with farmers from these communities owning and cultivating varying hectares. Main crops cultivated include rice, pepper, onion, tomato and okro. The scheme is regulated by the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority with the mandate of developing irrigation infrastructure to improve water and soil conservation practices.

Not all rice farmers in the Kumbungu district have access to the irrigation system, and those who do often cultivate rice outside the irrigation system as well. Water availability is a key concern for rice farmers, affecting numerous decisions throughout the cropping cycle. Increasing uncertainty about water availability conditions requires rice farmers to be adaptive in their decision-making by anticipating or responding to early or late onset of the rainy season, erratic rainfall, dry spells or excessive rainfall. Although rice farmers have the final responsibility to make rice cropping decisions, these decisions are embedded in broader set of decisions by other farmers and other actors, as part of both formal and traditional governance arrangements. The extent to which these governance arrangements enable adaptive decision-making is considerably under-studied.

The study addresses the overall question “How do rice farmers adapt their decisions to variability and uncertainties in water availability, and how are these decisions embedded in broader governance arrangements? The results section of this paper is divided into three parts with each part responding to a specific question. The first part is descriptive and addresses the question “which water-dependent decisions do rice farmers take and to what extent are these adaptive to changing water availability conditions?” Here, we identify key decisions and adaptive actions to manage water challenges. The second part probes into governance arrangements and establishes the tangle with decision-making by posing the question “what are the formal and informal governance arrangements in which rice farming decisions are embedded?’. The third part launches an inquiry into the governance arrangements-adaptive decision-making interconnection by posing the question “how do these governance arrangements enable or constrain adaptive decision-making in rice production systems?’. Following the answering of research questions, we further reflect on the potential of hydro-climatic information and Environmental Virtual Observatories (EVOs) in supporting adaptive decision-making and governance of rice production systems.

2 Theoretical framework

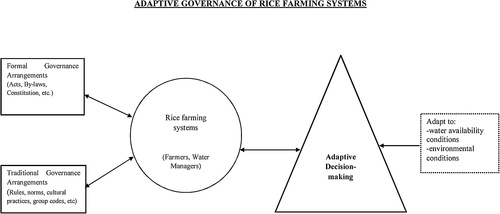

Adaptive governance has been cited as a guiding theory for understanding the dynamics of social-ecological systems and how these can be accounted for in governance arrangements and decision-making processes (CitationRijke et al., 2012; CitationTermeer et al., 2011; CitationOlsson et al., 2006). CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2016a) highlight the strength of adaptive governance as a theoretical lens as it integrates governance dimensions of adaptive capacity, collaboration, scaling, knowledge and learning. Thus, the capacities of social-ecological systems to respond and manage uncertain conditions could be better explored. Adaptive governance further allows for the engagement of both formal and informal institutions and cross-scale interactions (CitationGunderson et al., 2016). The concept has been defined in numerous ways. CitationDietz et al., (2003) coined the term adaptive governance in their paper on “the struggle to govern the commons”. They define adaptive governance as “managing diverse human-environmental interactions in the face of extreme uncertainty”. CitationWalker et al., (2004) present adaptive governance as “the process of creating adaptability and transformability in socio-ecological systems”. CitationGunderson and Light (2006) define adaptive governance as the set of institutions and frameworks that facilitate and foster adaptive management. In agreeing, CitationGreen et al., (2015) posit that adaptive governance is one way of bridging the dichotomy between legal structures that assume away uncertainty and adaptive management that focuses on acknowledging and winnowing uncertainty. In borrowing from CitationPlummer and Armitage (2007), and CitationFolke et al. (2005), CitationMunaretto et al.2014 refer to adaptive governance as “a continuous problem-solving process by which institutional arrangements and ecological knowledge are tested and revised in a dynamic, ongoing, self-organized process of learning by doing”.

CitationTermeer et al. (2011) define a governance arrangement as “the ensemble of rules, processes, and instruments that structure the interactions between public and or private entities to realize collective goals for a specific domain or issue”. They thus acknowledge the importance of accounting for both private and public actors, and their interactions. We define formal governance arrangements as “instruments and processes established by laws and treaties which are documented to be adopted as operational conditions in a given setting”. Traditional governance arrangements on the other hand as “culturally defined and sometimes undocumented rules and ways of behaviour integral in the social fabric of a people” (CitationTermeer et al., 2018; CitationWorden, 2010).

Another key concept for our analysis is adaptive decision-making (CitationChater and Oaksford, 2000; CitationWeber and Johnson, 2009). That adaptive governance arrangements will ultimately result in decisions that are adaptive to uncertain changes is often assumed but rarely studied. As different from the broader concept of adaptive governance, there is no readily available conceptualization of adaptive decision-making that we can rely on for our purposes. In essence, decision-making is about making choices between different decision options. The question here is to what extent the options chosen respond to observed or anticipated environmental conditions. The more variability and uncertainty in relevant environmental conditions, the stronger the need for decisions to be adaptive. We build on CitationRobert et al. (2017), who define adaptation in farm decision-making as “adjustments in agricultural systems in response to actual or expected stimuli through changes in practices, processes, and structures and their effects or impacts on moderating potential modifications and benefitting from new opportunities”.

To make the distinction between regular decision-making and adaptive decision-making, we will rely on the following operationalization. We understand regular decision-making as choosing standard decision options, based on generalized expectations of what to do under normal circumstances, but independent of the observed or anticipated environmental conditions that present themselves. In contrast, we understand adaptive decision-making as choosing non-standard decision options, in response to circumstances that are considered abnormal or unexpected (CitationPhillips, 1997). Thus, the decision-making process is perceived as a succession of decisions to be made, which can be more or less adaptive to changing circumstances.

The provision of relevant and timely information about observed and anticipated environmental conditions has the capacity to reduce risks and uncertainty in farmer decision-making (CitationLundstrom and Lindblom, 2018; CitationClarke et al., 2017). Information systems or observatories creating networks and enabling knowledge exchange amongst key actors in farming systems have also been central in discourse on improving farmer adaptation (Nie and Schultz, 2012). We thus reflect on the place of Environmental Virtual Observatories (EVOs) as discussed in CitationKarpouzoglou et al. (2016b). They use the terminology to describe a suite of information gathering, processing and dissemination technologies supported by World Wide Web that facilitate cross-fertilization of various sources of knowledge on shared virtual platforms. The theoretical framework of the study is graphically presented in .

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Case study

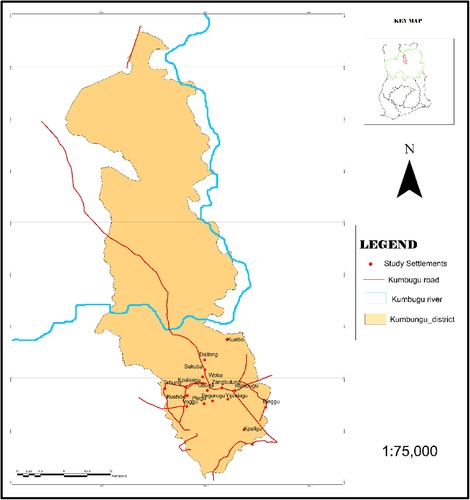

A case study research design (CitationBaxter and Jack, 2008; CitationStake, 2018) was adopted in conducting the study in Ghana. The study was undertaken in communities around the irrigation scheme in the Kumbungu district in Northern Ghana. The district is home to about 34,341 people with farming as a major economic activity. The Kumbungu district was carved out of the then Tolon-Kumbungu district in the year 2012. The irrigation scheme lies between latitude 9° 30″ and 9° 35″N and longitude 1° 20″and 1° 04″W and covers an area of 570 ha A total of sixteen farming communities were selected from upstream, mid-stream and downstream of the Bontanga dam. These include Bontanga, Wuba, Saakuba, Yiepelgu, Dalung, Voggu, Tibung, Kushibo, Kpalsegu, Zangbalun, Kumbungu, Gbugli, Kpalgu, Kpegu-Biegu, Kpegu-Bagurugu and Kpegu-Piegu. The study area is graphically presented in .

3.2 Data collection

The study through an exploratory approach uses qualitative methods to explore context specific conditions addressing research questions (CitationTaylor et al., 2015; CitationPatton, 2005; CitationDenzin and Lincoln, 1994). Study communities were sampled purposively (CitationEtikan et al., 2016; CitationDevers and Frankel, 2000). (See Figure Within each zone, 15 farmers practising either rain-fed rice farming only, irrigation rice farming only or both were purposively chosen and interviewed. In addressing the first specific research question, farmers were interviewed using unstructured interview guides (CitationRuane, 2005; CitationSchensul et al., 1999) (See Appendix A) for an average of 35 min. Farmers were mostly interviewed in their homes and farms (in a few cases). Questions centred on regular decisions farmers take, adaptive actions pursued in water management and the extent to which these were effective under changing conditions. Furthermore, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were organized with groups of an average size of 12 farmers in each community (CitationKothari, 2004; CitationStewart and Shamdasani, 2018). These served as avenues to further interrogate feedback received from direct interviews with farmers. Leaders of farmer groups, female and male farmers made up Focus Groups. FGDs were held at convenient meeting points where most farmers convey during leisure. Discussions allowed for brainstorming and an understanding of how governance arrangements influenced adaptive decision-making.

In probing into existing governance arrangements, farmers as part of direct interviews responded to questions on what governance arrangements were identifiable in communities and within the irrigation scheme. Rain fed rice farmers operated within the boundaries of traditional governance arrangements (CitationNchanji, 2017) whereas irrigated rice farmers had their activities framed around formal arrangements defined by the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority and the Ministry of Agriculture. As part of FGDs, farmers were engaged on what these governance arrangements are and how these influenced their operations. Chiefs, opinion leaders and local government representatives were also engaged. A document analyses was also undertaken to establish meaning from frameworks received from related authorities.

The third level of engagement revolved around how governance arrangements enabled or constrained adaptive decision-making. This enabled framing of the challenge of adaptive decision-making and formed an integral part of questions posed both during direct interviews and FGDs.

A summary of the research methodology is presented in .

Table 1 Research Methodology.

3.3 Data analysis

Firstly, field notes were synthesised to deduce relevant responses given the research questions. Recordings from interviews and FGDs were transcribed using Microsoft Word. Transcriptions were further analysed under key themes through a content analysis using the atlas.ti programme. Identifiable themes include stakeholder role play, water management practices, decision types, adaptive practices, formal governance arrangements, and traditional governance arrangements amongst others. Data was further synthesised to establish correlation between themes and for presentation.

4 Results

4.1 What decisions do rice farmers take in the Bontanga Area?

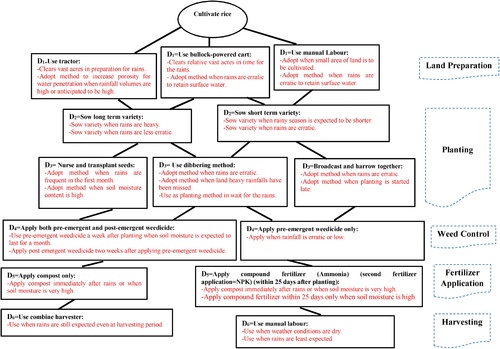

Farmers take six major decisions in the cropping cycle; decisions on whether to engage in rice farming, land preparation, planting, weed control, fertilizer application and harvesting (See ). These are regular decisions taken by farmers irrespective of the rice farming system being practiced and the varying conditions under which they operate. The sensitivity to water availability conditions can also be observed.

4.1.1 Rain-fed rice farming systems

Decision-making is an intra-household activity with men initiating and directing the process. Women and children almost readily respect and respond to the call to duty on the farm by the household head. The period between May–October within the year is of significance to rain-fed rice farming households as it is the only cropping time after which households are unable to engage in food production due to dry conditions.

The first key decision is whether or not to cultivate rice. For some households, this decision is the sole prerogative of the head (in most cases male) of the household. In some contexts, the head and spouse (or spouses if polygamous) discuss privately and communicate to the rest of the family. Rice is cultivated as a commercial crop thus, the decision is strategic and requires allaying all fears and risks the household envisions to be faced with, especially how to manage water needs on the farm. Household heads also consult other rice farmers in their communities in their outlook of the previous season and assessment of the prospects of the current season (see Box 1). Experiential and traditional knowledge play a key role at this point. Rainfall patterns and soil moisture content significantly determine decision outcomes at this point.

Decision-making amongst rice farmers.

“Before the season begins, rice farmers engage in dialogue to discuss expectations. Discussions revolve around water availability, access to seeds, farm machinery and fertilizer. We estimate the risk we have to face in the season by sharing our experiences, observations and information received”. -Anonymous (Rain-fed farmer in Kpegu-Piegu community).

“Most of the farmers cultivating rice in Dalung community are engaged in both rain-fed and irrigated rice farming. Our meetings are usually unstructured and could begin with few farmers sitting around. We spend more time together on Fridays after prayers at the mosque discussing challenges over the season with other farmers”-Anonymous (Rain-fed rice farmer in Dalung Community).

In the case where the farmer decides to cultivate rice, the next key decision is when to prepare the land. Rainfall levels and soil moisture content could influence the land clearance method adopted. Land is usually prepared when soil moisture content is high or estimated to be sufficient. Land preparation under regular conditions is usually done between April-May (see also CitationLaube et al., 2012; CitationLaux et al., 2008 for similar findings) using simple tools such as machetes and/or hoes, bullock-powered ploughs or tractors dependent on economic and physical factors. In Yielpegu, Zangbalun and Kpegu-biegu, some farmers own bullock-powered carts which they use for land clearance and ploughing on their farms. Owners of the aforementioned also render rental services to other farmers within and around their communities. Farmers pay for services in kind (2 bags of rice) or an equivalent in cash. In Kumbungu, Bontanga and Wuba, farmers pay between 200 and 450 Ghana cedis to engage tractor services for land clearance. An acre of land is averagely cleared in a day, two days or four days using a tractor, bullock-powered cart or simple hand tools respectively. Farmers’ ability to pay is no guarantee of access to services. Some farmers engage tractor services outside the district at a higher cost. Where necessary, some farmers are selected or volunteer to scout for tractor services for their communities.

Farmers proceed to plant after the aforementioned activities have been completed. Planting is usually done in July when there is enough rainfall but earlier should the rains set in June. Farm inputs such as labour, seed and water (soil moisture) are key pointers informing planting times. Seeds are planted directly through dibbering,Footnote 1 broadcasting, or nursed and transplanted after a given period.

Weed is controlled in a single or double phase dependent on farmers’ financial capacity. Pre-emergent weedicides are applied right after planting to control existing weeds. Post emergent weedicides are applied after rice begin to sprout. An average of two bottles of weedicides are applied on an acre of land by the farmer with the aid of family members.

The fifth major decision is on the application of fertilizer. Fertilizer is applied in early August but delayed when rains are erratic. Farmers obtain fertilizers from agro-chemical shops mostly in Kumbungu or Tamale. Fertilizers are applied when seeds sprout and also when the rice plant is observed to tassel. Fertilizers applied include NPK and manure from animal droppings. About two bags of fertilizer is applied at a time on an acre of rice farm. Soil moisture content or rainfall patterns are important drivers. In some cases, although farmers could afford a second phase of fertilizer application, low soil moisture content and erratic rainfall become barriers to undertaking the activity.

The last decision is on the harvest of rice. The activity is undertaken between the September and October. Most farmers engage labourers to augment efforts by the household in harvesting rice manually. Some farmers also engage the services of combine harvesters. Rice is then partially boiled or directly milled after and bagged for sale. Critical factors informing decisions on harvesting include market conditions, financial capacity, and estimated output from the farm.

4.1.2 Irrigated rice farming systems

Decision-making at the scheme level is led by the scheme manager guided by regulations of the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority. The guidelines establishing the scheme present it as a semi-autonomous entity thereby giving the manager the right to spearhead actions and day-to-day decisions at the local level. Instructions from the regional and national offices of the authority are however binding and considered in decision-making.

Periodic meetings are held at the beginning of the year to discuss operations under the scheme. Plans are designed under the leadership of the scheme manager with the support of farmers on water use, maintenance of laterals and effective farm management practices. Consultations are also initiated with external experts such as the GMet, Information Services Department (ISD), and District Assembly (DA) amongst others. Nevertheless, the scheme manager has power to decide on what volumes of water to be discharged unto farmlands. Block and lateral leaders are under the instruction of the water manager on the quantities of water to be discharged at any given point in time. Farmers within the scheme have to decide on whether or not to plant rice in the year. Here, risks are perceived to be lower than farming under the rain-fed system.

For most farmers, the decision to plant is dependent on whether they also engage in rice farming under rain-fed systems outside the scheme. Under such circumstances, resources are split to ensure production in and out of the scheme in the year. Most farmers within the scheme are able to cultivate rice all year round due to water availability. The dry season however comes with a challenge where low water levels affects water distribution to farmers whose lands are downstream. Irrigation charges and cost of renting lands within the scheme are also disincentives. In the case where farmers have the financial capacity to acquire land and ultimately secure land, the problem of water management is not enough disincentive to grow rice.

The next major decision is on land preparation. Farmers have access to power tillers from the irrigation authority and hence are less stressed in efforts to obtain machinery for land clearance. Furthermore, because lands are not left fallow for long due to all year round cultivation, farmers have little to clear on the land at any point in time. For farmers who are indigenes and live in communities around the scheme, farm labour required at this point is mostly provided by the household. Farmers who are non-indigenes and live outside the district hire labour from communities around the scheme when necessary.

The activity of planting is done using the broadcasting method or lines and pegs. In the case where pegs are used, farmers adopt the dibbering method and plant at intervals along the lines using pointed sticks/dibbers. Seeds are obtained from agro-chemical shops and in some cases through the leadership of the scheme where prospective buyers request for a particular variety to be cultivated. The decision to cultivate a particular variety however remains the sole prerogative of the farmer. Most farmers however opt for long term varieties as these are perceived to have higher yields when water is readily available for irrigation.

Weather conditions and adaptive decision-making.

“I relate the weather now to exactly what we experienced in the late 1970s. Rains have been erratic affecting my farming activities outside the scheme. The rains do not come in the month of May when I used to prepare my land. I have to wait till June or July after a few rains before preparing my land. This is a major challenge as I have no control over the rains and hence did not want to invest my limited profit into a possible failed harvest. I had to choose whether to cultivate rice, maize, raise livestock or support my wife with the money in her food vending business.”- Anonymous (Rain-fed rice farmer in Gbugli Community).

“A sense of how the weather will be at the beginning of the season is all we need as we have no options on how to meet water needs on our farms. Although my land is near the irrigation scheme, I do not have the machinery required to pump water from the dam unto my farmland. I therefore look up to the gods for a good year. This poses a lot of uncertainties on the way forward for us as rice farmers.”- Anonymous (Rain-fed rice farmer in Sakuuba Community).

Weed control is done individually but in some cases in consultation with other farmers who share boundaries to avert identified diseases which have tendencies of spreading. Decisions on disease and weed control are sometimes discussed collectively at the scheme level when identified. In consultation with technical staff at the irrigation authority, farmer decisions at the farm level are also informed by inputs on the best practices of the day for weed and disease control. Farmers also benefit from technical advice as part of interventions such as the Ghana Commercial Agriculture Project (GCAP). Labour for weed control is provided by the household or hired. Both pre-emergent and post-emergent weedicides are applied dependent on farmers’ financial capacities.

The decision on when and what type of fertilizer to apply on the farm is taken at the farm level. Fertilizers are applied through a process of sprinkling or strategic placement across the farmland. Fertilizer types used are mostly same as those applied under the rain-fed system.

The decision on harvesting is made by the farmer guided by pre-conditioned factors in instances where there are buyers with specific interests. The scheme manager in providing support to farmers also solicits for buyers who purchase rice in large quantities. Farmers thereby engage in collective actions and decision-making at this stage.

4.1.3 How adaptive are decisions to water availability conditions under both systems?

Water availability is integral for rice production. With uncertainties in rainfall patterns and weather conditions, farmers (especially under rain fed systems) have to adapt to conditions that could affect their productivity and output. From the study, it is evident that farmers at each decision point make choices aimed at managing water scarcity (See ). The outcomes of decision options and how these facilitate adaptive water management on the farm is fundamentally defined by both controllable and uncontrollable factors.

Hydro-climatic information and farmer experiential knowledge are key at this point. The absence of or inadequacy of long term information on variability in weather conditions is detrimental to productivity especially when yields from the previous season are low (see Box 2). Farmers at each point have to be adaptive in their decision-making to maximize decision outcomes, learning and attainment of new knowledge where possible.

Following the decision to cultivate rice, farmers have to deal with the challenge of preparing their lands at the ‘right’ time. Unpredictability of weather conditions and limited access to some farm inputs make it challenging. Under rain-fed systems, the decision to use tractor could come with the risk of high cost of service and longer waiting period to access tractor affect timely land clearance. Thus access to tractor translates into timely land clearance for the rains. For some farmers, a less expensive option will be to use bullock-powered carts which although not as quick as tractors are cost saving and timely as well. For other farmers manual labour is an option when land size is smaller. Under irrigated farming systems, the availability of water for irrigation presents less stress in adaptive decision-making. Irrespective of which method is used in land clearance, farmers are able to meet water needs on their farms. This however comes at a cost as farmers pay fees for irrigation services. However, methods that enable time saving could increase the chances of the farmer completing the season in good time.

Adaptive decision-making also involves choosing the type of seed variety to cultivate. Long term varieties are a better hedge against flooding. Maturity periods are however longer and present a risk of stunted growth and low harvest should the rains be erratic. Thus for most rain-fed rice farmers whose farms are more than 100 m from the banks of the Bontanga river, planting short term varietiesFootnote 2 is a more adaptive option. However, majority of short term varieties have higher market value thus an adaptive step could be to face the risk of water scarcity and aim at higher returns on sale of produce.

On planting, the broadcasting or dibbering method is least time consuming and best method when planting is delayed or rainy days have been missed. Both activities are time consuming and could slow adaptation to rainfall conditions. Broadcasting is common amongst rain-fed rice farmers considering low financial and labour capital requirements. However, farmers face difficulty in applying fertilizer in due time. Nursing and subsequent transplanting is best when preparations are started early and projected rainfall will be high.

Farmers during weedicide application consider soil moisture content after sowing. Pre-emergent weedicides are applied at least 7 days after sowing in case soil moisture content is high and post emergent weedicides after seeds sprout. Weedicides in some contexts are not applied at all due to delayed rains and sprouting and thus an anticipated failed harvest. For farmers who cultivated lands both in and out of the scheme in the season, weedicides are channelled only to land cultivated inside the scheme. The post weedicide application period is where most farmers lament and hence deem it as the ‘tipping point’ of the season. This is as a result of the inability of farmers to control conditions on the farm after this point. Thus, unfavourable conditions with regards to water availability is a recipe for disaster and a sign of a possible failed harvest at the end of the year.

Adapting to water scarcity requires a consideration of decision outcomes during fertilizer application. The first option is to apply compost within 2 weeks after planting. Soil moisture content must be high to improve the assimilation of fertilizer by the crop. This nevertheless does not guarantee higher yields hence the need to apply a second fertilizer (Ammonia) within 25 days after planting under good water conditions. For some farmers, risks associated with water is so high and hence not worth it applying fertilizer at allFootnote 3 as low or no rains result in failed harvests.

Expected outcomes at harvest time is a bountiful harvest. Water scarcity is not an immediate consideration during harvest time. Farmers consider using combine harvesters or manual labour for harvesting. Given the fact that preceding conditions such as water availability and soil fertility have direct impact on yields, adopting the most effective method in harvesting to reduce losses is a pre-requisite. Generally, the harvest from most rain-fed rice farms in 2016/17 is one-fourth of what farmers harvested in the wet season the previous year. Thus adaptive decisions involve using combine harvesters which is time efficient and reduces crop loss. For other farmers, the evidence of failed or a good year is predictable relational to activities preceding the activity of harvesting. Thus, a manual harvesting method could be used to save financial resources.

4.2 What governance arrangements exist in rice farming systems?

Two types of governance arrangements can be identified in rice farming systems. Within the irrigated rice farming system, formal governance arrangements with legal orientations can be seen to shape activities and interactions. Traditional governance arrangements although pre-dominant in rain-fed rice farming systems had an impact on activities in irrigated rice farming.

4.2.1 Rain-fed farming systems

Under rain-fed systems, decision-making is less coordinated and centres on household and community members. At the onset of the season, farmers mostly consult members of their households in taking decisions. Other farmers within the community are also consulted when planning for the season. Farmer decisions are shaped by the rules and norms largely defined by communities. Communal decision-making is led by traditional authorities, religious leaders and locally elected leaders such as the Assembly member. Conflicts amongst farmers are also resolved at chief palaces under the leadership of chiefs and elders. Chiefs as custodians of communal owned resources such as land and water resources ensure all inhabitants are able to meet water needs. For rice farmers, meeting household water needs is equally a priority as water for irrigation purposes. The chief’s palace is thus a safe haven to manage conflicts on water use.

Men wield a lot of authority at the household level as heads of households. Traditionally, land is willed to male members of the household as women are expected to eventually change names after marriage. Household names are thus traced through male descendants. This automatically limits the ability of female farmers to access land or expand area under cultivation. Women involved in rice farming mostly work with their spouse. Culturally, women are perceived as “helpers” and hence are required to support their spouses on the farm rather than cultivate vast acres of land. Hence, the potential of women is limited to their engagement by their husbands. The high sense of communalism serves as a useful resource in meeting labour costs on farms. Here, rice farmers receive labour support from other community members for reciprocation on their farmlands. This is typically the case in smaller communities such as Kpegu-Biegu, Voggu and Kpegu-Bagurugu.

4.2.2 Irrigated rice farming

Operations within the scheme are guided by formal governance arrangements at the national, regional and local levels. At the national level, the Ghana Irrigation Development Authority (GIDA) gives mandate to operations within the scheme. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Water Resources Commissions (WRC) grant user rights on water use for irrigation purposes. Operations at the scheme level are led by the Manager. The scheme manager periodically consults the Ghana Meteorological Agency (GMet) for weather information which guides decisions on water use. The Savannah Research Institute (SARI) also provides scientific information to inform agronomic practices.

The scheme manager leads decision-making at the scheme level. Technical decisions on management of the dam and ancillary facilities within the scheme are matters of interest. Farmer associations exist with leadership responsible for liaising between farmers and management. Farmlands are put in blocks with leaders responsible for managing laterals and monitoring water distribution for irrigation purposes. A schedule is drafted at the beginning of the year on how and when water will be discharged to laterals. Block leaders work closely with leaders of their respective farmer associations for farm level decision-making. Sub-committees set up (as part of L.I 350 of the Irrigations Development Authority) to augment efforts of the manager include the Maintenance, Finance, Marketing and Welfare committees. Traditional authorities whose lands fall within the catchment area of the dam and own farmlands are also primary stakeholders in the context of decision-making on water use. Traditional authorities are also consulted by the scheme manager in managing conflicts on water use.

4.3 How do governance arrangements enable or constrain adaptive decision-making?

Considerably, governance arrangements impact adaptive decisions made under both farming systems. These arrangements in some context propelled and improved adaptive decisions whereas other arrangements appeared as limiting factors.

4.3.1 Rain-fed rice farming

Governance and decision-making are not mutually exclusive under the rain-fed system. Farmers who cultivate rice under this system operate within the cultural and social settings shaping norms, rules and beliefs in their communities. For example, although farmers take decisions at the household level, they are expected to adhere to directives from chiefs, unit committee members, the assembly member, other leaders even if unfavourable but in the interest of the community. With the existence of multi users of the Bontansi River, rice farmers are required to consider the interests of other users such as other crop farmers, livestock keepers and households. From Section 4.1.1 rain-fed rice farmers mostly rely on the weather in meeting water needs for activities such as planting. Farmers equally explore alternatives such as the use of small water pumps to discharge water from tributaries of the Bontansi River unto their farmlands. The scuffle for water by various users sometimes results in pollution of the water making it unwholesome for their use. This poses a challenge to farmers in meeting water needs and adaptive decision-making. Cultural practices within communities for example prohibit women from leading the decision-making process especially in male headed households. This has impact on their input on key decisions. Thus adaptive decision-making is male centred limiting the possibility of reducing risks and social learning. As seen in Section 4.1.1, land is also mostly owned by men thereby limiting the ability of women to contribute directly to increasing production under uncertain water sensitive conditions.

Nevertheless, the spirit of communalism is an enabler of adaptive decision-making in some circumstances. For example, the fact that rice farmers live within the same community as some owners of bullock-powered ploughs enable access to their services on credit when they have to prepare their lands for planting as presented in Section 4.1.1. Labour needs during planting are also met as a result of ‘labour-for-labour’ governance arrangements. Here, farmers take turns to support each other during planting, fertilizer application and harvesting. This enhances the capacity of farmers to adaptively decide their actions. Strong community cohesion patterned by traditional rules of engagement also allow for collective decision-making in managing challenges of water availability. From Section 4.1.1 it is evident that farmers spend time interacting and sharing knowledge in open spaces at random or agreed times at all stages of their decision-making. In Sakuuba for example, community meetings organised by chiefs afford them the opportunity to discuss water conflicts and how best to manage them. Through adaptive decisions, water users within the community are able to improve water management practices which equally translate to better conditions of water availability for rice farming.

4.3.2 Irrigated rice farming

The regulatory framework (L.I 1350-Ghana Irrigation Development authority Act, 1987) defining operations within the irrigation scheme explains authority and power relations. Here, the Scheme manager is seen as the final authority at the scheme level and hence controls water user rights. Under the leadership of the scheme manager, periodic meetings are held for broad decisions which affect all actors within the irrigation scheme. This usually comprises of the scheme manager, water bailiffs, block leaders, lateral managers and farmers. Thus, key decisions as outlined under Section 4.1.2 begin with discussions which have water management at the core. Thus strategic water dependent adaptive decision-making begins at the managerial level with most tactical decisions taken by farmers at the farm level. For example, from Section 4.2.2, water bailiffs guided by agreed schedules discharge water to irrigate farmlands. Farmers however take the tactical adaptive decisions of water sufficiency on their farms. Farmers monitor their farms and are able to control inflow to avoid flooding. The presence of scheduled timelines for irrigation highly influences farmer decisions on when to plant, apply weedicides and also fertilizer on their farmlands.

Contrastingly, farmers can also not decide to discharge water to irrigate their farms at their own timing but rather follow agreed schedules even during emergencies. During dry seasons, water discharge comes with power play with some chiefs continuously receiving water on their farmlands at the expense of other farmers. Also, laterals 1–7 conveniently access water even during the dry season as opposed to laterals 8–14. The exhibition of powers thus creates a situation where Chiefs, leadership of farmer groups and farmers favoured by them are mostly able to secure lands within laterals 1–7. Thus for farmers with less influence, their decisions must consider such risks and how these could be constraints towards adaptive decision-making. In essence, water dependent adaptive decision-making is not mutually exclusive of rules and processes already defined as part of water management strategies and agreements.

The institutional space within which stakeholders relate significantly impacts decision making processes and outcomes. These include formally entrenched frameworks such as constitutions, ad-hoc rules of engagement and organograms defining hierarchy and power in public and private spheres. Similarly, undocumented laws, rules and norms which are usually embedded in the cultural fabric of communities explicitly or implicitly construct the process of decision-making, framing the boundaries for who, what and when decisions could be made. Adapting in a highly volatile environment such as the one in which rice farmers operate requires a continuous process of cognitive revision through experimentation, learning and re-adjustment in adaptive decision-making.

The existence of a regulatory framework within the scheme also means that farmers operate in line with communication and power symmetries. From Section 4.2.2, the lateral manager (one voluntary farmer plays this role at a particular time) is the first point of contact for farmers should they have challenges with water flow on their farmlands. He is then expected to forward concerns to the water bailiff in the absence of an immediate solution. With the scheme manager at the end of the bureaucratic complaint chain the timing of farmer decision and implementation of adaptive actions in relation to water management on their farms is affected. From Section 4.2.2, farmers, as a rule, are required to desilt canals that convey water unto their farms. Thus, for a farmer downstream, the efficient and timely undertaking of this activity by another farmer upstream is critical. For example, soil moisture at the point of fertilizer application must be high or sufficient. In the case of non-adherence by some farmers to desilt canals, those downstream potentially are faced with stunted growth of their rice due to low moisture conditions. The weak implementation of punitive measures also means that farmers who refuse to clear their laterals could only be cautioned by block leaders and/or lateral managers. The existence of informal relationships and the culture of respect for ‘senior citizens’ within communities limit the ability of lateral managers to enforce rules to the core. Leaders of farmer associations equally enjoy some priority when farmers are to benefit from interventions such as trainings, seminars and out-of-farm collaborative arrangements with private institutions. The absence of a system for knowledge transfer also means that leaders who benefit from such capacity building are not obliged to transfer knowledge acquired. Hence, some farmers are at risk of losing relevant information which could improve their adaptive decision-making.

5 Discussion

In this section, we discuss the implications of our results and the relationship between key concepts as studied in both rice farming systems. We further attempt a so-called ex ante reflection spelling the potential of hydro-climatic information to inform adaptive decision-making. We further estimate how governance arrangements could enable or inhibit information access for adaptive decision-making. In essence, our conclusions and propositions related to the potential of hydro-climatic information and EVOs in adaptive decision-making is based on reflections.

5.1 Reflection on key concepts: adaptive governance and adaptive decision-making

In our attempt to contribute to theoretical dispositions on adaptive governance of food systems, the study focused on governance arrangements and adaptive decision-making in rice farming systems. It emerged that governance arrangements evolved with learning and experimenting in adaptive decisions-making. An inverse relationship could also be identified with adaptive decisions being streamlined in response to adaptive governance arrangements (See also CitationFeola et al., 2015). Both conditions are due to the consistent shift in ecological variables such as river discharge, temperature and rainfall rendering supposed solutions expressed in adaptive decision-making becoming part of the problem or rather ineffective thereby requiring newer strategies and actions. Also, formal and traditional governance arrangements were found to be interwoven given the involvement of farmers in both systems. In establishing further the place of both governance arrangements in adaptive decision-making, the study concludes that formal governance arrangements must have traditional governance arrangements as sub-structures in their design or a complement of both.

We conclude that studies on adaptive governance of food systems must empirically explore the relationship between governance arrangements and adaptive decision-making (especially in water governance) (See also CitationRouillard et al., 2013; CitationDewulf et al., 2011). We equally admit that although the study stepped out to study adaptive governance, it focused on only two key components of the theory; governance arrangements and adaptive decision-making. Thus, our conclusion will better reflect the theory only in the context within which it has been applied.

5.2 Governance arrangements and the potential of hydro-climatic information

5.2.1 Under rain-fed systems

Traditional governance arrangements put Chiefs and other community leaders at the forefront of decision-making within communities. Inhabitants of communities willingly submit to calls from the aforementioned for collective action and decision-making on matters of importance. The platform created by traditional leaders serves as a medium for information dissemination necessary for decision-making amongst rice farmers. Citizens as part of religious routines pray together at mosques and churches located within their communities. This creates avenues for channelling information. Also, farmers as a result of social networks defined by culture and lifestyle meet periodically to socialize and this creates an avenue for information sharing and exchange.

On the other hand, tradition also requires that community entry begins with consultation with Chiefs and community leaders. This arrangement means information service providers in trying to engage rice farmers must seek consent from Chiefs as they are the custodians of the land and rulers of the people. In the instant where permission is not granted, rice farmers will lose relevant information which goes a long way to improve their decisions. Also, citizens esteem knowledge handed over from older generations. In the instance where information from external providers contradict their traditional knowledge and processes, some farmers will reject new knowledge and continue with the old way of doing things. This can translate into low acceptance and use of new knowledge resulting in knowledge conflicts putting farmers at crossroads as to the way forward. Thirdly, weak interactions between the District Assembly and communities can limit the impact of programmes aimed at providing farmers with information through public sector programmes. The absence of rice farmer associations in communities could limit the dissemination of hydro-climatic information should they be made available. Although rice farmers meet periodically within communities, activities are less structured with no conclusive actions taken in pursuit of hydro-climatic information.

5.2.2 Within the irrigation scheme

Hydro-climatic information has can improve farmer decision on water use. CitationSam and Dzandu (2016) also attest to information relevance for food production in Ghana. This is however dependent on the extent to which governance arrangements make such possible. Arrangements within the scheme present a clear structure for information flow and decision-making. The scheme manager as part of overseeing general operations within the scheme channels relevant information either through leaders of farmer associations, members of ad-hoc committees or directly to farmers at meetings. Such organised arrangements create the opportunity for directly communicating hydro-climatic information received for use by farmers. Currently, the partnership between GMet and GIDA has yielded positive outcomes such that GIDA is able to receive information on rainfall projections as estimated by GMet. Such information contributes to informed decisions on water use within the reservoir. However, the all year round availability of water in the dam for irrigation purposes within the scheme limits the urgency and need for hydro-climatic information. The variation in water level nevertheless makes it relevant to track hydro-climatic conditions via relevant information sources. Communication processes must adopt smart approaches such as the use of social platforms for quick dissemination of information where applicable.

5.3 Potential hydro-climatic information for adaptive decision-making

The availability of timely and reliable hydro-climatic information at each phase of decision-making can improve adaptation (see also CitationWood et al., 2014) efforts in rice production systems. Farmers rely on traditional knowledge with some receiving information on daily weather forecasts. However, obtaining information on daily precipitation and temperature values which are area specific could improve adaptive decisions at different decision points (See also CitationAker et al., 2016). Hydro-climatic information received at the community level informs the planning of daily schedules for water discharge for irrigation within the scheme.

At the onset of the rainy season, the scheme manager together with farmers within the scheme design a daily schedule for water discharge from the dam unto farmlands. Here, information on rainfall and temperature values can contribute to a more precise strategy and outcome (see also CitationFosu-Mensah et al., 2012; CitationKemausuor et al., 2011). For example, the water manager will be able to estimate likely water volumes within the dam. Plans on supplementary irrigation could be improved as information from GMet and private institutions show the periods where the area is likely to experience heavy rainfall. Information on temperature values for the area could also come in handy during the dry season when the rains have seized for effective planning on water use from the dam.

For farmers under rain-fed systems, information on daily and seasonal rainfall values could guide their decisions on whether or not to engage in rice farming as most rely on the rains directly to meet water needs on their rice farms. Chiefs, religious leaders, radio and local political representatives such as the Assembly member could serve as channels for information dissemination to farmers within communities (see also CitationAker and Fafchamps, 2014; CitationSam and Dzandu, 2016). During land preparation, information on rainfall is equally relevant for farmers under rain-fed systems. Here, farmers are able to plan the number of days they have to use in clearing their lands to avoid being caught up in heavy downpour which makes it difficult to use machinery such as tractors and tillers on the land. During planting farmers decide on whether to cultivate short term or long term varieties guided by experience and projections on rainfall for the season. Readily available information on daily precipitation comes in handy in making choices on variety to plant. The story at the point of fertilizer application is no different. Information on precipitation has the tendency of guiding decisions on what quantities of fertilizer to apply and when. This will curb the situation where fertilizer applied is washed away by the rains adding up to cost burdens and losses mostly borne by the farmer and his household.

5.4 EVOs and adaptive governance

Technology based platforms are today being developed to support natural resource governance through information management, improved stakeholder interaction and decision-making (see also CitationTermeer and Bruinsma, 2016; CitationPimm et al., 2014). Decisions on irrigation and water use for example can be improved if farmers and water managers have access to timely information from relevant institutions. In adaptive decision-making discourse, information must not just be available but also timely and relevant for farmers and water managers.

Currently, two systems of governance exist in rice production systems in the Bontanga area with an enormous number of stakeholders involved. The situation has resulted in poor and unregulated interaction limiting the ability to deal with complex challenges faced by rice farmers. As it emerged, the Bontansi River is central to the activities of all rice farmers irrespective of which system they operated in. Hence creating the opportunity for stakeholder collaboration in water management could be beneficial. As argued by CitationTermeer and Bruinsma (2016) however, there is the need to bridge physical, cognitive and social boundaries. EVOs thus present an opportunity for collaborative governance by providing the platform for interactive engagement, information sharing and the leap over social boundaries (CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2016b).

In the case of water management, an EVO that provides timely information and enables stakeholders to consolidate observed changes in weather conditions can essentially improve decisions on water use for irrigation. Here, the GMet, ISD, water managers and farmers can directly contribute to predicting weather indices irrespective of their location and rice production system being practiced. Local knowledge used by farmers in predicting the weather could be synthesised with scientific knowledge to improve predictability and make adaptation more locally relevant. Chiefs and leaders in communities studied could sensitize and stir interest of all stakeholders in communities to contribute to information gathering, discussions and creation of new knowledge for adaptive decision-making. Given that stakeholders under both systems admit to water dependent decision-making, a coordinated process which brings stakeholders together could be the beginning of realising the goal of an operational EVO for water management.

6 Conclusions

The study establishes a correlation between governance arrangements and adaptive decision-making in adaptive governance. Evidence from the field suggests that adaptive decision-making within irrigated and rain-fed rice production systems vary. Farmers under both systems operate within different governance arrangements which are both enablers and inhibitors given conditions. For adaptive governance of rice farming systems within the area, there must be a synergy of both formal and traditional governance arrangements as these are not mutually exclusive. Following our ex ante evaluation on the place of information in adaptive decision-making, we point to the need for further research on information access and use, power play, gender and information systems enabling information exchange and knowledge creation which essentially influence water dependent adaptive decision-making.

In Bontanga, bottlenecks to information exchange must be considered in the design of Environmental Virtual Observatories. Much appropriately, research on what information systems exist and how these are operationalised within current governance arrangements is critical. Water availability is central in both the design of governance arrangements and adaptive decision-making within the study area. This emphasises the significance of hydro-climatic information in the area hence the need to study what information exists, the knowledge they provide and the systems being deployed to disseminate them.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the numerous partners funding the EVOCA programme and research. We also thank the management of the Bontanga Irrigation Scheme and farmers who availed themselves to be part of the study and continuously support the EVO design process.

Notes

1 A dibber is a pointed wooden stick for punching holes in the ground.

2 Varieties include AGRA, Moses and Jasmine

3 After the rains refused to come for an average of 4 weeks.

References

- T.A. Adongo F.K. Abagale G. Kranjac-Berisavljevic Performance of Irrigation Water Delivery Structures in Six Schemes of Northern Ghana 2015

- J.C. Aker M. Fafchamps Mobile phone coverage and producer markets: evidence from West Africa World Bank Econ. Rev. 29 October (2) 2014 262 292

- J.C. Aker I. Ghosh J. Burrell The promise (and pitfalls) of ICT for agriculture initiatives Agric. Econ. 47 November (S1) 2016 35 48

- F.A. Asante F. Amuakwa-Mensah Climate change and variability in Ghana: stocktaking Climate 3 December (1) 2014 78 99

- A. Bawayelaazaa Nyuor E. Donkor R. Aidoo S. Saaka Buah J.B. Naab S.K. Nutsugah J. Bayala R. Zougmoré Economic impacts of climate change on cereal production: implications for sustainable agriculture in Northern Ghana Sustainability 8 August (8) 2016 724

- P. Baxter S. Jack Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers Qual. Rep. 13 4 2008 544 559

- A.G. Bhave D. Conway S. Dessai D.A. Stainforth Barriers and opportunities for robust decision making approaches to support climate change adaptation in the developing world Clim. Risk Manage. January (14) 2016 1

- I. Braimah R.S. King D.M. Sulemana Community-based participatory irrigation management at local government level in Ghana Commonwealth J. Local Govern. July (15) 2014 141 159

- H. Buhaug T.A. Benjaminsen E. Sjaastad O.M. Theisen Climate variability, food production shocks, and violent conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa Environ. Res. Lett. 10 December (12) 2015125015

- B.C. Chaffin A.S. Garmestani D.G. Angeler D.L. Herrmann C.A. Stow M. Nyström J. Sendzimir M.E. Hopton J. Kolasa C.R. Allen Biological invasions, ecological resilience and adaptive governance J. Environ. Manage. December (183) 2016 399 407

- N. Chater M. Oaksford The rational analysis of mind and behavior Synthese 122 February (1–2) 2000 93 131

- N. Clarke J.C. Bizimana Y. Dile A. Worqlul J. Osorio B. Herbst J.W. Richardson R. Srinivasan T.J. Gerik J. Williams C.A. Jones Evaluation of new farming technologies in Ethiopia using the Integrated Decision Support System (IDSS) Agric. Water Manage. January(180) 2017 267 279

- N.K. Denzin Y.S. Lincoln Handbook of Qualitative Research 1994 Sage Publications, Inc

- K.J. Devers R.M. Frankel Study design in qualitative research--2: sampling and data collection strategies Educ. Health 13 July (2) 2000 263

- A. Dewulf M. Mancero G. Cárdenas D. Sucozhanay Fragmentation and connection of frames in collaborative water governance: a case study of river catchment management in Southern Ecuador Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 77 March (1) 2011 50 75

- T. Dietz E. Ostrom P.C. Stern The struggle to govern the commons Science 302 December (5652) 2003 1907 1912

- I. Etikan S.A. Musa R.S. Alkassim Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 5 January (1) 2016 1 4

- G. Feola A.M. Lerner M. Jain M.J. Montefrio K.A. Nicholas Researching farmer behaviour in climate change adaptation and sustainable agriculture: lessons learned from five case studies J. Rural Stud. June (39) 2015 74 84

- C. Folke T. Hahn P. Olsson J. Norberg Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. November (30) 2005 441 473

- B.Y. Fosu-Mensah P.L. Vlek D.S. MacCarthy Farmers’ perception and adaptation to climate change: a case study of Sekyedumase district in Ghana Environ. Dev. Sustain. 14 August (4) 2012 495 505

- O.O. Green A.S. Garmestani C.R. Allen L.H. Gunderson J.B. Ruhl C.A. Arnold N.A. Graham B. Cosens D.G. Angeler B.C. Chaffin C.S. Holling Barriers and bridges to the integration of social–ecological resilience and law Front. Ecol. Environ. 13 August (6) 2015 332 337

- L. Gunderson S.S. Light Adaptive management and adaptive governance in the everglades ecosystem Policy Sci. 39 December (4) 2006 323 334

- L.H. Gunderson B. Cosens A.S. Garmestani Adaptive governance of riverine and wetland ecosystem goods and services J. Environ. Manage. December (183) 2016 353 360

- T. Karpouzoglou A. Dewulf J. Clark Advancing adaptive governance of social-ecological systems through theoretical multiplicity Environ. Sci. Policy March (57) 2016 1 9

- T. Karpouzoglou Z. Zulkafli S. Grainger A. Dewulf W. Buytaert D.M. Hannah Environmental Virtual Observatories (EVOs): prospects for knowledge co-creation and resilience in the information age Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. February (18) 2016 40 48

- F. Kemausuor E. Dwamena A. Bart-Plange N. Kyei-Baffour Farmers perception of climate change in the Ejura-Sekyedumase district of Ghana ARPN J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 6 19 2011 26 37

- C.R. Kothari Research methodology: methods and techniques New Age Int. 2004

- G. Kranjac-Berisavljevic R.M. Blench R. Chapman Rice Production and Livelihoods in Ghana: Multi-Agency Partnerships (MAPs) for Technical Change in West African Agriculture 2003 ODI Ghana

- W. Laube B. Schraven M. Awo Smallholder adaptation to climate change: dynamics and limits in Northern Ghana Clim. Change 1 April (3–4) 2012 753 774

- P. Laux H. Kunstmann A. Bárdossy Predicting the regional onset of the rainy season in West Africa Int. J. Climatol. 28 March (3) 2008 329 342

- C. Lundstrom J. Lindblom Considering farmers’ situated knowledge of using agricultural decision support systems (AgriDSS) to Foster farming practices: the case of CropSAT Agric. Syst. 159 2018 9 20

- S. Munaretto G. Siciliano M.E. Turvani Integrating adaptive governance and participatory multicriteria methods: a framework for climate adaptation governance Ecol. Soc. 19 June (2) 2014

- E.B. Nchanji Sustainable Urban agriculture in Ghana: what governance system works? Sustainability 9 Novemer (11) 2017 2090

- P. Olsson L.H. Gunderson S.R. Carpenter P. Ryan L. Lebel C. Folke C.S. Holling Shooting the rapids: navigating transitions to adaptive governance of social-ecological systems Ecol. Soc. 11 June (1) 2006

- M.Q. Patton Qualitative Research 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.Oct

- S.D. Phillips Toward an expanded definition of adaptive decision making Career Dev. Q. 45 March (3) 1997 275 287

- F. Pietrapertosa V. Khokhlov M. Salvia C. Cosmi Climate change adaptation policies and plans: a survey in 11 South East European countries Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. July 2017

- S.L. Pimm C.N. Jenkins R. Abell T.M. Brooks J.L. Gittleman L.N. Joppa P.H. Raven C.M. Roberts J.O. Sexton The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection Science 344 May (6187) 20141246752

- R. Plummer D. Armitage A resilience-based framework for evaluating adaptive co-management: linking ecology, economics and society in a complex world Ecol. Econ. 61 February (1) 2007 62 74

- W. Quaye Food security situation in northern Ghana, coping strategies and related constraints Afr. J. Agric. Res. 3 May(5) 2008 334 342

- J. Rijke R. Brown C. Zevenbergen R. Ashley M. Farrelly P. Morison S. van Herk Fit-for-purpose governance: a framework to make adaptive governance operational Environ. Sci. Policy October (22) 2012 73 84

- M. Robert A. Thomas M. Sekhar S. Badiger L. Ruiz H. Raynal J.E. Bergez Adaptive and dynamic decision-making processes: a conceptual model of production systems on Indian farms Agric. Syst. October (157) 2017 279 291

- J.J. Rouillard K.V. Heal T. Ball A.D. Reeves Policy integration for adaptive water governance: learning from Scotland’s experience Environ. Sci. Policy November (33) 2013 378 387

- J.M. Ruane Essentials of Research Methods: A Guide to Social Science Research 2005 Blackwell publishing

- J. Sam L. Dzandu The use of radio to disseminate agricultural information to farmers: the Ghana agricultural information network system (GAINS) experience Agric. Inform. Worldwide February (7) 2016 17 23

- S.L. Schensul J.J. Schensul M.D. LeCompte Essential Ethnographic Methods: Observations, Interviews, and Questionnaires 1999 Rowman Altamira

- R.E. Stake Qualitative Case Studies 2018

- D.W. Stewart P.N. Shamdasani Focus Group Research: Exploration and Discovery 2018

- S.J. Taylor R. Bogdan M. DeVault Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource 2015 John Wiley & SonsOctober

- C.J. Termeer A. Bruinsma ICT-enabled boundary spanning arrangements in collaborative sustainability governance Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. Febuary (18) 2016 91 98

- C. Termeer A. Dewulf H. Van Rijswick A. Van Buuren D. Huitema S. Meijerink T. Rayner M. Wiering The regional governance of climate adaptation: a framework for developing legitimate, effective, and resilient governance arrangements Clim. Law 2 January (2) 2011 159 179

- C.J. Termeer S. Drimie J. Ingram L. Pereira M.J. Whittingham A diagnostic framework for food system governance arrangements: the case of South Africa NJAS-Wageningen J. Life Sci. March (84) 2018 85 93

- B. Walker C.S. Holling S. Carpenter A. Kinzig Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems Ecol. Soc. 9 September(2) 2004

- E.U. Weber E.J. Johnson Mindful judgment and decision making Ann. Rev. Psychol. January (60) 2009 53 85

- S.A. Wood A.S. Jina M. Jain P. Kristjanson R.S. DeFries Smallholder farmer cropping decisions related to climate variability across multiple regions Glob. Environ. Change March (25) 2014 163 172

- L. Worden Notes from the greenhouse world: a study in coevolution, planetary sustainability, and community structure Ecol. Econ. 69 February (4) 2010 762 769

- J.A. Yaro The perception of and adaptation to climate variability/change in Ghana by small-scale and commercial farmers Reg. Environ. Change 13 December (6) 2013 1259 1272

- J.A. Yaro J. Teye S. Bawakyillenuo Local institutions and adaptive capacity to climate change/variability in the northern savannah of Ghana Clim. Dev. 7 May(3) 2015 235 245

Appendix A

Survey Instruments

Interview Guide For Farmers

Begin the interview by introducing yourself. For example “My name is Andy. I am a PhD student from Wageningen University in the Netherlands. I am currently undertaking a study with the aim of understanding the challenges you (rice farmers) and water managers’ face with water which is essential for your farm activities. I aim to understand what decisions you have to make under what conditions and how these decisions have shaped your practices. I will therefore be glad if you could spare sometime so we discuss how you manage your daily activities on the farm and what decisions you make so as to ensure water availability for your farm activities.”

Interview Checklist

A. Background of Farmer

1. Can you please tell me a bit about yourself (age, education, occupation, etc.)?

2. If you have a family, can you tell me about them (family size, age of children, gender, etc)?

B. Information on the community and social relations

3. How long have you lived in this village?

4. How do you think the natural environment in this community has changed over the years?

5. What is your opinion on community relations in this village?

6. Do you think community leaders as chiefs and assembly members are still influential in affairs in the community? Explain.

C. Land Tenure and Farming in the Village

7. Who owns lands in this village and how can one access land for farming?

8. What are the common arrangements between landowners and farmers who do not own lands?

9. What major farm crops are cultivated in this village and why?

10. Are there sometimes disputes about land? How are these settled?

D. Governance and decision-making at the farm level

11. As a rice farmer, what are the decisions you have to take every farming season?

12. Considering the decisions mentioned, how does one decision affect the other?

13. Which decisions do you take alone and why?

14. Which decisions do you usually take with the rest of the family and why?

15. What are the roles played by you and other family members on the farm?

16. How do you define or determine the roles each family member plays?

E. Governance and decision-making at the group level

17. In the case where you do, who do you interact with during decision-making in the farming season who are not family members?

18. What decisions do you make with them and why?

19. What decisions don’t you make with them and why?

F. Water management decisions in rice production

20. What factors do you think affect water availability during the rainy season as well as the dry season?

21. What decisions do you take on water use during the rainy season in irrigated/non-irrigated rice production to ensure continuous water availability?

22. What decisions do you take on water use during the dry season in irrigated/non-irrigated rice production due to ensure continuous water availability?

23. What actions do you take as a farmer engaged in irrigated/non-irrigated rice farming as part of water management on your farm?

24. How effective were the actions you took in the just ended production season on water use?

25. What do you think accounted for the failure or success of the decisions you took last season on water use?

G. Adaptive decision-making on water management in rice production

26. What are some of the decisions you had to quickly change last season when you noticed failure of rains and other water sources you use?

27. How easily are you able to change decisions on water use due to change in circumstances such as the rains, temperature and the weather during rice production?

28. Tell me about a certain event and how did you react (get stories) (rice culture) (decision practices in rice farming) (dealing with water availability can follow later)

29. Do you know the extent to which other farmers have been flexible with adaptive decision-making?

30. Did the new ad-hoc decisions you took contribute positively to your rice production process?

H. Improving adaptive-making in water management

31. How do you think farmers can improve the decisions made in water management in rice production?

32. How do you think collective decision-making could better improve adaptive decision-making than individual decisions or otherwise?

33. Any other comments?

Thank You For Your Time

Interview Guide For Water Managers

Begin the interview by introducing yourself. For example “My name is ………. I am a PhD student from Wageningen University in the Netherlands. I am currently undertaking a study with the aim of understanding the challenges you (water managers) and rice farmers face with water required for rice farming. I aim to understand what decisions you have to make under what conditions and how these decisions have shaped rice production practices. I will therefore be glad if you could spare sometime so we discuss how you manage your daily activities in the scheme and what decisions you make so as to ensure water availability for rice production.”

Interview Checklist

I. Background of Water manager

1. Can you please tell me a bit about yourself (age, education, occupation, etc.)?

2. If you have a family, can you tell me about them (family size, age of children, gender, etc)?

J. Water manager role play

3. How long have you been working as a water manager on this irrigation scheme?

4. Have you managed similar irrigation schemes before?

5. How do you think this scheme differs from the previous one you managed?

6. Do you think there are lessons from your past experience that have shaped your present performance? If so how?

7. How relevant do you think the role of the water manager is in the overall management of the scheme?

K. Stakeholder Analysis and decision-making

8. What frameworks define role play and decision-making in the irrigation scheme?

9. Which stakeholders do you take decisions with in the irrigation scheme?

10. At what stages of the farming process do you engage with these stakeholders?

11. What decisions do you take alone as a water manager and why?

12. What decisions do you take with other stakeholders and why?

13. If you had your own way, which stakeholders will you like to work closely with and why?

14. If you had your own way, which stakeholders will you not like to work closely with and why?

Water management in the Scheme

15. What are the water related challenges you face in the scheme?

16. What are the decisions you have to take due to challenges in water availability for the smooth operation of the scheme in both rainy and dry seasons? Which of these do you take together with farmers?

17. What decisions are you easily able to change especially in the dry season?

18. What decisions are you not able to change in the dry season?

19. How are the decisions you are able to change affect water availability?

20. How do the decisions you are unable to change affect water availability?