Abstract

Rural communities in Africa are facing numerous challenges related to human health, agricultural production, water scarcity and service delivery. Addressing such challenges requires effective collective action and coordination among stakeholders, which often prove difficult to achieve. Against the background of the increased availability of information and communication technologies (ICTs), this article synthesizes the lessons from six case-studies reported in this Special Issue. The cases investigate the possible role of digital citizen science platforms (labelled EVOCAs: Environmental Virtual Observatories for Connective Action) in overcoming the challenges of integrating heterogeneous actors in collective management of common resources and/or the provision of public goods. Inspired by the seminal work of Elinor Ostrom, our expectation was that such platforms could help operationalize communication and information-related design principles and community conditions that are known to enhance the capacity to address environmental challenges.

This article presents some cross-cutting insights and reflections regarding the nature of the challenges identified by the diagnostic studies, and on the relevance and significance of Ostrom’s framework and analysis. It also reflects on the plausibility of our original ideas and assumptions by assessing what the various studies tell us about the significance and potential of key components of an EVOCA-type intervention: i.e. environmental monitoring, ICT, connective action, citizen science and responsible design. At the same time, we draw lessons for follow-up research and action in our research program and beyond by identifying several issues and themes that merit further investigation.

Based on the case-studies, we conclude that many collective action challenges are of a more complex nature than originally anticipated, and often cannot be resolved within clearly demarcated communities. While this complicates the realization of Ostrom’s communication and information-related design principles and community features, there may still be a meaningful role for digital citizen science platforms. To help address complex challenges, they must be oriented towards fostering adaptive and systemic learning across interdependent stakeholder communities, rather than focusing on the self-betterment of the communities alone. Such digital platforms need to be developed in a responsible manner that ensures complementarity with already existing patterns of communication and ICT-use, that anticipates dynamics of trust and distrust among interdependent stakeholders, and that prevents typical problems associated with the sharing of information such as privacy infringement and undesirable control over information by outsiders.

1 Introduction

The social and bio-physical processes and dependencies that determine the magnitude and spatiotemporal dynamics of complex agro-ecological problems are under-researched in a number of settings (CitationForan et al., 2014; CitationFischer et al., 2015). As the manuscripts in this Special Issue almost univocally pronounced, we still lack comprehensive longitudinal data on the dynamics of infectious plant diseases and vector-borne livestock infections, while projections on how climate change is going to affect water availability and farming conditions are only available at the aggregate levels, having little relevance for small-holder farmers (CitationLevin et al., 2012; CitationBerkes et al., 2003).

Perhaps even less is known in science and policy networks about the way in which the communities dealing with these challenges interact with their difficult environments, and how this interaction determines their livelihood options as well as regional food security (CitationGloede et al., 2013). Yet, these everyday micro-decisions taken at the local levels are going to determine whether the problems in question get tamed or exacerbated beyond their current contexts (CitationNgaruiya and Scheffran, 2016).

The core underlying assumption of the interdisciplinary research program Responsible life-sciences innovations for development in the digital age: Environmental Virtual Observatories for Connective Action (EVOCA) was that coordinated, ICT-enabled collective action can provide a successful strategy for a bottom-up community-level response. In the Introductory paper of this Special Issue (CitationCieslik et al., 2018) we have outlined the environmental challenges that arise from the interaction between human activity and bio-physical processes in our six case-study settings: the management of common resources (water scarcity in rice-irrigation systems in Ghana, pasture and water shortage in Kenya); the management of common threats (crop disease epidemics in Ethiopia and Rwanda, vector-transmission of malaria in Rwanda and parasite-borne diseases in Kenya); and the provision of public goods (extension and credit services for smallholders in Ghana). We argued that addressing such challenges typically requires collective action and coordination among stakeholders, and pointed to the relevance of CitationOstrom’s (1990) work on community based governance of common resources. CitationOstrom (2009) identified a number of design principles and community features that influence whether or not communities succeed in fostering effective cooperation in managing the commons or creating public goods, and several of these relate closely to information provision and communication capacity within communities (see also CitationPoteete et al., 2010). Ostrom’s research indicates that communication must be practically feasible among all community members who are using or producing a resource. Similarly, cooperation is more likely to emerge when participants can monitor the extent to which users benefit from and contribute to a resource, and have access to information that helps them to assess the reputation and behavior of others. Having reliable information about the condition of the resource (based on regular environmental monitoring) is also found to contribute to cooperative behavior. While such conditions need to be combined with e.g. recognition of local users rights to govern, arrangements for conflict resolution and effective community-based rules and sanctioning systems, it is clear that availability of information and possibilities for pervasive inter-user communication are of paramount importance for the effective management and (re)production of common resources (CitationOstrom, 1990). In the context of the rapid expansion of mobile ICT use in African countries, we proposed that digital platforms may enable the operationalization of such design principles and community features in new ways, and thus enhance the capacity to address environmental challenges. Specifically, we assumed that digital platforms may have the potential to:

| 1) | enhance the feasibility of communication within communities that use or produce a resource, and possibly change the boundaries of effective community formation; | ||||

| 2) | improve information provision about the resource and its use(rs) by facilitating and accelerating the data collection and data processing that is part and parcel of community-based monitoring activities; | ||||

| 3) | support the co-creation of relevant knowledge by making community-based monitoring part and parcel of citizen science activities that add value to available information (e.g. by fostering linkages with science based models and other databases, or by enriching interpretative discussion about the meaning and implications of information); | ||||

| 4) | strengthen the capacity of local communities to organize via connective action, which constitutes a new form of collective mobilization that is less reliant on formal organizational coordination. | ||||

The papers in this Special Issue present the findings of eleven diagnostic studies (CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018; CitationNyamekye et al., 2018; CitationNyadzi et al., 2018; CitationMunthali et al., 2018; CitationAgyekumhene et al., 2018; CitationMurindahabi et al., 2018; CitationAsingizwe et al., 2018; CitationMcCampbell et al., 2018; CitationChepkwony et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018) investigating the potential of virtual platforms for information accumulation, processing and exchange (EVOCAs) to help the relevant stakeholders overcome the collective action challenges. To this end, interdisciplinary teams were asked to unravel the bio-physical and social dimensions of the problematic situations, assess how current practices relate to information, interpretation, knowledge and connectivity, and reflect on whether, where and how EVOCA type platforms could make a difference. In addition, teams were encouraged to reflect on possible pitfalls and on how an EVOCA design process could be organized in a responsible manner.

In the closing paper of this Special Issue we take stock and reflect on the plausibility of our ideas and assumptions and draw lessons for follow up action and research. First, we present some cross-cutting insights and reflections regarding the nature of the challenges at hand, and on the relevance and significance of Ostrom’s framework and analysis. We then reflect on what the diagnostic studies tell us about significance and potential of key components of an EVOCA-type intervention: i.e. environmental monitoring, ICT, connective action, citizen science and responsible design. In doing so, we identify several issues and themes that merit further investigation and attention in our action research program and beyond.

2 The nature of the collective action challenges in the EVOCA cases

Elinor Ostrom’s observations regarding common pool resources and public goods are based on case-studies demonstrating that communities may well be able to redress opportunistic behavior of users of or contributors to a resource, thus preventing its over-use and degradation (CitationOstrom et al., 1994). The six case studies in our research program all represent complex problems that could potentially be addressed through effective collective action, but that have proven to be persistent. In light of our ambitions, it is important to reflect on why this is the case.

2.1 Limited recognition of the collective management challenge

Most of the diagnostic studies have managed to identify a range of biophysical, technical, socio-cultural, economic, institutional and political factors that play a role in reproducing the problem situation. In , we select some factors from the diagnostic studies that seem to affect collaboration and implementation of management options.

Table 1 Status of community-based collaboration and key factors affecting it.

One important common denominator that transpires from is the apparent lack of awareness of the collective nature of the respective socio-environmental challenges: different actors and stakeholder groups tend to make uncoordinated, disconnected attempts that remain largely ineffective. The authors conclude that the stakeholders do not explicitly acknowledge that they are faced with a collective management challenge, which contributes to the relative absence of community-based initiatives. This is, for example, true for the potato diseases (CitationDamtew et al.,2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018), banana wilt (CitationMcCampbell et al., 2018), tick-borne diseases (CitationChepkwony et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018), and also for extension and credit provision (CitationMunthali et al., 2018; CitationAgyekumhene et al., 2018). In relation to the tick control case, we see forms of organization among pastoralists that do, however, prioritize other issues, and we see in the water case that existing forms of collective management are government-led and oriented towards distributing available water, rather than dealing with the scarcity itself. In the malaria case there exist government induced community action teams that promote preventive measures at household level (e.g. use of bed nets), but are less focused on managing the broader ecological environment (CitationMurindahabi et al., 2018; CitationAsingizwe et al., 2018). Arguably, this situation relates not only to issues of knowledge and awareness, but also to how responsibilities for dealing with the issues at hand have evolved historically. In many of the cases we see that there are authorities operating at higher levels than the community (e.g. governmental bodies for public health, irrigation management, crop protection or service delivery) that have a mandate to deal with the problematic situation, and this may contribute to the phenomenon that local communities do not assume a leading role in taking action. In Ghana, for example, farmers are not likely to feel responsible for contributing to extension provision as they simply regard this to be a government responsibility, and in Rwanda the government seems to play such a dominant role in governing the management of banana wilt that there is little space left for communities to design their own rules. While there may be very good reasons to have higher level authorities overseeing challenges that exist in many communities (or that may travel between them, such as in the case of diseases), the way in which such institutions operate may also foster situations where the need or possibility to address issues at the level of clearly bounded communities becomes less self-evident (CitationShah, 2006).

2.2 ‘Public bads’ do not always require a public good response

A circumstance that may relate to the low degree of community-based organization is that –accidentally- many of our cases center around diseases. From the perspective of Ostrom’s classification of goods, one could say that the disease itself is neither a common pool resource nor a public good. Arguably, it represents a ‘public bad’: a negative phenomenon from which it is difficult to exclude people, and that does not diminish when people gain access to it. In such cases, the potential public good is actually the opposite, namely the (preventive or curative) community-based disease management strategy to which people may contribute or not. However, our case studies suggest that disease management cannot be automatically regarded as a public good of which the creation is strongly dependent on effective collective action. In the case of banana wilt, for example, it is argued that single diseased stem removal is a very effective strategy that individuals can apply to reduce damage in their farms, although it does not fully eradicate the disease (CitationMcCampbell et al., 2018). This reduces farmers dependence on others, hence moving prevention away from a good that can only be created through collective management. For bacterial wilt in potato, it is clear that disease management has public good features since combatting the disease can only be achieved through effective collaboration among farmers, while potato late blight is a disease that rich farmers can effectively manage by intensive spraying (turning disease management in the direction of a private good), while poor farmers depend on collective action (CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018). What we see here is that public good features of a disease management strategy depend on specific agro-ecological features of the disease, the available technological options and also on group or community specific social conditions and resources. Relevant variables may e.g. include the spreading mechanism, spreading radius, herd effects, tolerance of crops, persistence of the disease over time, the efficacy of preventive or curative measures, and on whether access to these depends on market relations or not.

All this simultaneously implies that whether or not a disease management strategy has (or may be recognized as having) public good features is also dependent on the knowledge and understanding that is available among scientists and/or societal stakeholders. It is, for example, important that the causal pathogen, its life cycle, its ecology and the resulting symptoms are known. In other words: depending on the knowledge and information people have about pathogens, vectors, diseases and possible solutions, they may perceive a high or low social interdependence (i.e. a need for collective action) in disease management. Moreover, even though the disease management strategy might be a ‘public good’ from a scientists’ perspective, the farmers might not perceive it as such. See for example the case of bacterial wilt in potato in Ethiopia, where farmers and other stakeholders appear to have limited understanding of the disease.

In view of the above, the relevance and significance of Ostrom’s design principles and features of micro situations are also bound to depend on such agro-ecological and technical characteristics. When the disease travels fast (e.g. certain insects, infested seed tubers) and far (e.g. spores of late blight; infested seed tubers of potato), disease management is not merely a local affair. This means that the required face-to-face interaction is not always feasible. Similarly, reputations are often not known for farmers at longer distance.

2.3 Acknowledging greater complexity

The insights referred to above suggest that several of the problem situations that we are dealing with have a greater level of complexity than can be resolved through community-based management. In the literature, the level of complexity of a challenge is usually defined along two axes (e.g. CitationJasanoff, 1990; CitationFuntowicz and Ravetz, 1993; CitationHisschemoller and Hoppe, 1996): (a) the extent to which parties involved agree on problem definitions and goals to be achieved (with more disagreement implying higher complexity), and (b) the extent to which there exists uncertainty about how the system at hand functions and may be influenced (with higher uncertainty implying more complexity). Recently, CitationArkesteijn et al. (2015) have added a third dimension: the degree of stability in the problematic context, as related to e.g. path dependencies created by earlier choices, the strength of dominant coalitions and interest groups and/or the malleability of bio-physical environments (with higher stability adding to complexity). From our previous discussions (see also ), it transpires already that several of the cases are affected by factors that point towards a higher degree of complexity, such as conflicts among stakeholders, limited understanding of diseases and rigidity in political systems. In we synthesize more in detail how the cases may be characterized in terms of their level of complexity.

Table 2 Crude characterization of the cases in terms of levels of complexity.

As can be noted from , most of the cases in the EVOCA program can be seen to have a fairly high level of complexity, whereby it is striking that especially the level of stability in the system seems to be a complicating factor. In addition, we see that uncertainty seems to be high in only two of the cases, and that even when there is agreement on the existence of a problem, there is still considerable disagreement on how to respond, despite the availability of considerable knowledge. Such disagreement then seems to relate to issues like who is (politically) responsible or to blame, and/or what means and strategies should be employed by whom. In several cases (e.g. potato diseases in Ethiopia, malaria and banana wilt in Rwanda, see also ) we see that local or higher level officials have interest to hide information about the problem for political reasons, thereby shifting the risk and responsibility to farming communities who clearly cannot resolve the issue on their own. Such communities, in turn, blame authorities or other stakeholders for not taking sufficient action, or for taking measures that are not realistic. Under these kinds of high complexity conditions, it is questionable whether the environmental challenges can be addressed through community-based action in similar ways as documented by Ostrom. In most of our cases, the relevant community boundaries are not self-evident and the roles and responsibilities between different governance levels are contested or undefined. Similarly, this greater level of complexity may complicate the operationalization of Ostrom’s design principles in situations where these are not yet established and where there is no tradition yet to organize collective action in response to the particular challenge (e.g. in all cases related to plant diseases and service delivery). Fostering clear boundaries and agreed upon rules is likely to be difficult, and the feasibility of collecting relevant and credible monitoring information may be reduced. And even if more information were available, such information might again be shielded off for political reasons and/or become part of further contestation about the implications of the information for whom should act and how. In all, we see that the environmental challenges we are dealing with tend to be complex and persistent, which implies that they are unlikely to be resolved with a targeted intervention (CitationBrown et al., 2012; CitationNorton, 2012).

In the next section we will reflect on the implication of these insights for the idea that EVOCAs may play a role in addressing collective action challenges in our case-studies, focusing on both: the potential of participatory monitoring and citizens science and the increased connectivity function (connective action).

3 The role of EVOCAs in addressing complex challenges: observations and themes for further investigation

As we argued in the previous section, the authors in this Special Issue unravel the case studies as particularly complex, embedded, socio-environmental problems. Importantly, it is often their social complexity, rather than their technical complexity, that makes complex problems so hard to address. CitationConklin (2006) notes that complex problems cannot be addressed using the traditional linear modes of problem solving, shifting the focus towards continuous monitoring, adaptation and learning, and a long-term horizon. CitationMoore (2010) argues that creating a shared understanding between the stakeholders about the problem, and shared commitment to the possible solutions, is the first step in designing a response or resolution strategy. This implies that issues pertaining to knowledge and information remain important, even if we cannot expect these to provide unequivocal answers and directions. Indeed, the contributions to this Special Issue indicate that there are a number of information gaps that may hamper the efforts to successfully manage complex socio-environmental problems, including insufficient data, inconsistent metrics, lack of predictive models, and the absence of real-time monitoring systems (CitationBates and Scarlett, 2013; CitationJerven, 2013). While increasing numbers of stakeholders – from governments and large development organizations through research centers and private companies to local and national agricultural extension centers – engage in data collection, their activities are mostly uncoordinated and the resulting data often remain underutilized, and it is far from self-evident that such metrics translate into usable, actionable knowledge for stakeholders operating at various levels, including – in our cases – farmers and herders.

This makes it pertinent to reflect on the process of acquiring the data, evidence and knowledge within their contexts of application. In connection with this, we organize our analysis and discussion along three lines: considerations regarding the significance of environmental monitoring (the E and O components of EVOCAs) in providing relevant information for dealing with the issues at hand, the plausibility that ICT may have added value in generating such information (the V component of EVOCAs), and the relevance of the idea of ‘connective action’ in the various contexts (the C and A components of EVOCAs). We then carefully examine the respective diagnostic studies from the point of view of citizen science, and reflect on how ideas regarding responsible innovation are applied in the various cases. In relation to each topic, we reflect on relevant lines for future research.

3.1 The significance of environmental monitoring: broadening the scope

Diversity in meaning and timing – In all cases, we see that there is an expectation that collecting information about the environment from various sources (including citizens) may help to generate new information that was not previously available, and which may usefully enrich or be combined with scientific understandings or models (e.g. about disease risk), or with information from other sources and/or scale levels (e.g. weather forecasts). At the same time, it is interesting to note that what is considered relevant environmental information diverges considerably. In some cases, the emphasis is on collecting ecological information such as tick or mosquito densities (CitationMurindahabi et al., 2018; CitationAsingizwe et al., 2018; CitationChepkwony et al., 2018), while in others the emphasis is on collecting local knowledge such as the status of indigenous predictors for rainfall (CitationNyamekye et al., 2018; CitationNyadzi et al., 2018) or on incorporating pastoralist’s knowledge on how proposed measures for tick control may be adapted to local socio-economic conditions (CitationMutavi et al., 2018). In the case of service delivery, the emphasis is on capturing relevant human characteristics and practices, for example past performance of farmers in terms of agricultural productivity or credit repayment (CitationMunthali et al., 2018; CitationAgyekumhene et al., 2018). In few cases, we see that a combination or integration of both ecological and social information monitoring – as suggested by CitationOstrom (2009) – is proposed. An exception is the potato case that proposes to not only collect information about disease occurrence and agro-ecological conditions, but also on adherence of farmers to agreed-upon preventive practices as part of a control system (CitationOstrom, 2009). This simultaneously implies a difference in the decision-making stage that is being addressed. In most cases we see that environmental monitoring serves to foster collective awareness and learning (e.g. through visualization of geo-referenced ‘early warning’ data) to inform future courses of action, while the potato case also proposes to use monitoring as a way of evaluating whether preventive or curative actions are taken by community members. At the same time, while Ostrom argued in favour of locally legitimized rules, the complex problems exemplified by the cases might require more multi-level and adaptive institutional arrangements.

Notably, the link we have forged between the idea of Environmental Virtual Observatories (EVOs, see CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2015) and environmental and social monitoring as proposed by CitationOstrom (1990) is original, and extends beyond the roles of EVOs discussed in literature so far (CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2015). Future research will have to demonstrate whether this is indeed a worthwhile conceptual and practical endeavor. As part of this, it will be interesting to assess the value of different types, forms and purposes of environmental monitoring in different settings, including whether these involve commons, public goods and/or public bads. Do we see different patterns depending on whether monitoring serves awareness raising versus the control of community agreements? Does it matter whether monitoring informs (or is informed by) formal scientific knowledge and understanding (or ‘techne’) or whether it aims to capture localized practical skills and experiential intelligence (or ‘metis’) (CitationScott, 1998; CitationMutavi et al., 2018)? Another critically important question that is so far largely overlooked in our case-studies (and beyond) is how the design of environmental monitoring systems may usefully intertwine with the design of rules and sanctioning systems that are binding and effective in fostering collective action, but also flexible enough to adapt to changing conditions? This links and adds a dimension to a broader discussion on what might motivate and incentivize people to collect and share data in the first place, and how this might vary across situations and cultures (see CitationBeza et al., 2017). When monitoring becomes part and parcel of agreed upon community-based governance systems, data collection may actually become a regulated and compulsory activity.

A need for greater precision and ‘informational validation experiments’? – While all authors have positive expectations about the potential of environmental monitoring in their case-studies, it is not always clear yet what kind of information is to be collected exactly, and what and whose decisions are to be informed by the resulting insights to alter the dynamics in the complex problem context. What information about bacterial wilt in potato or banana may be decisive in altering stakeholder’s views and intentions? And how could or should enhanced information on likely rainfall patterns inform and alter water distribution decisions of irrigation authorities, cropping patterns of farmers, or advisory communication by extension agents? What and whose actions are likely to be most influential in addressing malaria prevalence or human-wildlife conflict, and what monitoring information might be essential for these actors? On what social and/or institutional information do credit providers base their current decisions, and what information might lead them to transform their practices? So far, it is mostly assumed that having better information will somehow help several parties involved to operate more effectively, but such expectations are not yet truly validated. This is still an insufficient basis for making design choices about the technical, informational and social dimensions of an environmental monitoring system.

In view of the above, an important question is how we may move ahead with our research to arrive at better grounded and more targeted design priorities before making further investments. One option may be to use small choice experiments or games in which stakeholders are offered specific information in a specific form and in a specific (hypothetical or real) situation, and to evaluate with stakeholders how this does or may influence key decisions and (inter)actions (CitationHarrison and List, 2004). In this way, the likely efficacy and consequences of different options for information collection and presentation may be explored and discussed as a basis for further decision-making on EVOCA design. An advantage of such choice experiments is that PhD researchers and EVOCA designers can generate faster feedback on options than would be possible if they would follow only the real-life rhythms of agricultural growing seasons and/or the ecological cycles of pests and diseases. Clearly, responses in hypothetical settings or games may meaningfully differ from actual behaviors in real settings, but at the same time it may be a practical way forward within the relatively short time horizon of a PhD project. Moreover, such choice experiments could be designed and evaluated together with stakeholders, and be used to foster in-depth discussion that informs both research and collaborative decision-making about EVOCA design.

3.2 The added value of ICT

A continued need for/significance of conventional media – We signaled in the previous section that the precise informational characteristics of environmental monitoring systems are yet to be clarified in most cases. This also holds for the choice of media and ICT platforms that may be part of an EVOCA. In most articles in this Special Issue, it is assumed that mobile platforms (especially phones) have added value in the process of data collection, and it is also clear that for such purposes options based on text messages still have a far greater reach in the short term than internet services, since the latter are by no means commonly accessible for farmers and other citizens. While the added value of ICT in collecting data may be plausible, it is far less clear whether ICTs have added value when it comes to the presentation and communication of findings from data analysis, and for fostering interpretative discussion and exchange to arrive at conclusions. Very few articles address this question, but implicitly for most cases in this Special Issue it is assumed that their EVOCA will need to include conventional forms of communication and exchange in the form of community meetings (CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018; CitationMurindahabi et al., 2018; CitationAsingizwe et al., 2018), group activities (CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018; CitationMcCampbell et al., 2018), multi-stakeholder platforms (CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018; CitationNyamekye et al., 2018; CitationNyadzi et al., 2018), conflict resolution strategies (CitationChepkwony et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018), face-to-face extension visits and/or radio broadcasting (CitationMunthali et al., 2018). It is relevant to note that such conventional spaces for interaction are likely to be more suitable for the kind of interpretative discussion and dialogue that is needed in complex multi-stakeholder problem situations. Hence, it is clear that ICT cannot stand on its own and will have to be combined with a broader package of media and methods. This conclusion also arises from the only case study where ICT platforms have already been introduced in the field (i.e. tailor-made service delivery in Ghana, CitationMunthali et al., 2018). The use of these platforms appears to be affected by a range of technical and institutional challenges, while pre-existing networks, communication patterns and media appear to have strengths that are not easily matched by ICT applications (CitationMunthali et al., 2018). This latter finding is congruent with conclusions derived from similar studies, demonstrating that traditional forms of communication remain essential in settings were modern ICT are used (CitationSulaiman et al., 2012; CitationDehnen-Schmutz et al., 2016). More in general, communication scientists suggest that old media (e.g. newspapers or radio) do not disappear when new media application have been developed, but rather that they take on new or more specific functions (CitationJenkins, 2006).

In all we see that it would be a mistake to only consider mobile ICT platforms as useful components of an EVOCA; such platforms should rather be embedded in and combined with traditional media. In line with studies indicating that ‘virtual’ and ‘non-virtual’ forms of interaction in communities may mutually re-inforce each other (CitationMateria et al., 2015), future research could focus on how conducive task divisions and mixes between ‘old’ and ‘new’ media may be achieved as components of EVOCAs or EVOs (CitationKarpouzoglou et al., 2015). At the same time, research may be oriented to analyzing the public and/or private governance arrangements that underpin the implementation of both conventional media and ICT platforms, and the extent to which these hinder or support conducive articulation between media combinations.

What about actual and everyday uses of mobile ICT? – The papers in this Special Issue reflect that most case-studies engage with ICT from the perspective of ‘how can new ICT opportunities be used to address complex challenges?’. Essentially, this has connotations of a technology push approach, where relative outsiders think about introducing something new to help overcome perceived problems. Given the nature of the EVOCA program and the specific set-up of our diagnostic studies (CitationCieslik et al., 2018) this may be understandable or even partially unavoidable, but this should not prevent us from trying to avoid the well-known risks of technology push, such as insufficient attention to existing practices, user contexts and purposes. Given that mobile technologies (especially mobile phones) have already spread considerably, a relevant question would also be ‘how and why are new ICTs (and for that matter conventional media) already used in the context of complex challenges?’. This question received relatively little explicit attention in the diagnostic studies, with the exception of the tick-borne diseases case (CitationChepkwony et al., 2018) and to some degree the tailor-made service delivery case (CitationMunthali et al., 2018). Yet, there are indications that exploring this might yield relevant information. The latter case, for example, revealed that there is quite some use of mobile ICTs besides formally introduced applications and platforms. Farmers and extension agents frequently contact each other by phone, as do agents and traders (CitationMunthali et al., 2018; CitationAgyekumhene et al., 2018). Moreover, extension agents interact amongst themselves and with researchers through Whatsapp groups (CitationMunthali et al., 2018). Similarly, the case on tick-borne diseases suggests that pastoral herders make intensive use of mobile phones, and coordinate a number of activities (including grazing, disease control and land invasions) through such media (CitationChepkwony et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018 ; see also CitationDe Bruijn et al., 2016). Thus, rather than assuming that something new needs to be introduced, we may learn a lot from how and why people have already integrated novel ICTs in their communication with others, and from whether or not they experience added value from this.

Directing future research towards a more in-depth understanding of the logic of such existing patterns of communication and information exchange is in line with a more anthropological approach to studying everyday ICT-use (CitationDe Bruijn and Van Dijk, 2012; CitationBrinkman et al., 2017). Such in-depth studies may provide further insight in the complex problem context and help to further target and specify where opportunities lie for complementary EVOCA-like platforms. If, for example, it would appear that traders or aggregators provide working capital and credit to farmers based on the personal judgement of experienced agents, it may be less important to invest resources in the systematic collection of data on the past performance of farmers (CitationMunthali et al., 2018; CitationAgyekumhene et al., 2018). And if pastoral herders and ranch managers indicate that they can coordinate tick-borne disease management through regular mobile phone contact, and rank insecurity and human-wildlife conflict as more pertinent and less controllable problems than tick-borne diseases, then we should indeed wonder whether tick-borne diseases are indeed the right entry point for an EVOCA-type intervention (CitationChepkwony et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018). Thus, such in-depth studies of existing communication patterns and contents may also serve to reconsider taken-for-granted assumptions regarding the desirable features of ICT platforms. As access to social media increases in African countries, such studies may usefully include analysis of social media contents and networks to gain insight in diverging views and coalitions around these (CitationStevens et al., 2016).

3.3 From connective action to connectivity

As is elaborated in the introductory chapter of this Special Issue, the notion of connective action was introduced by CitationBennett and Segerberg (2012) to refer to a novel mode of organizing through the sharing of personal expressions and action frames in especially social media networks, as experienced in e.g. the Arab Spring. We recognized from the outset that there could be obstacles to such a dynamic in the kinds of settings we are dealing with (i.e. externally induced citizen science initiatives and low internet access and digital literacy), and indeed these obstacles were encountered. In fact, none of the cases considers social media and personalized action frames to be a significant component of their EVOCA as yet. This is likely to be related to the current media landscape in rural communities where social media do not yet play an important role, except perhaps in the Kenyan case-study where rural youth and chiefs were reported to link up with political action networks about a conservation and human-wildlife conflict through Whatsapp (CitationChepkwony et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018). The modest attention to social media may also be fostered by our in-built emphasis on environmental monitoring and citizen science that may have drawn the attention towards ‘data’ rather than personalized content. Nevertheless, interesting forms of social media use where also identified among researchers and extensionists in Ghana (CitationMunthali et al., 2018), which could be interpreted as a new way of organizing and mobilizing against pests and diseases within professional networks. Further analysis will have to reveal to what extent features of organizationally-enabled connective action are indeed present and/or emerging. Notwithstanding the specific examples from Kenya and Ghana, it is pertinent to conclude that our case-study interventions are not likely to foster ‘connective action’ as described by CitationBennett and Segerberg (2012), but rather build on enhanced connectivity for purposes of environmental monitoring and/or citizen science. While this is expected to result in engagement and action (CitationMurindahabi et al., 2018; CitationAsingizwe et al., 2018; CitationNyamekye et al., 2018; CitationNyadzi et al., 2018; CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018), this seems to be more directed towards more conventional forms of collective and community action. Yet, given the speed with which mobile internet and smartphones are gaining ground, the significance of the notion of connective action may be meaningfully greater in 10 years’ time.

Even though true ‘connective action’ is not likely to play a role in our cases, it remains relevant and important to further test the novel idea that ICT enhanced connectivity and communication capacity of groups can help to increase the individual members’ likelihood to contribute to a collective goal (see CitationOstrom, 2009). In doing so, it would be interesting to contrast situations where the contribution serves to realize a collective long term gain (i.e. the creation of a public good or the maintenance of a common pool resource) with situations where cooperation serves to avoid a collective loss (i.e. the control of ‘public bads’). Such comparative research may build on the research approaches already adopted in the various case studies, but - as suggested earlier in relation to the need to further validate what is relevant information for whom - this future research line might also benefit from using games or ‘lab-in-the-field’ experiments similar to those conducted by e.g. CitationMilinski et al. (2008). In such a game, groups of respondents could be asked to respond to collective environmental challenges during several consecutive rounds, where by the members of the treatment group (in contrast to the control group) are provided with phone credit and a list of their group members’ telephone numbers to facilitate communication. What we would hope to observe is that the respondents who received call credit and phone numbers would call each other (connect) in between the subsequent rounds of the game and probe other group members for their planned behavior, establish personal bonds and/or develop a collective identity, or prevent free-riding behavior (if observed) via negotiation. Thus, they would be more likely to contribute to the collective target and not to free-ride on others than the control group for whom communication and connectivity would be less easy and more costly. Of course, game protocols and scenarios should be tailored to the specific features of our cases, which together offer considerable potential to compare e.g. public good and public bad situations.

3.4 The promise of citizen science: benefits to research and society in addressing complex challenges

Most contributions to this Special Issue acknowledge the value of linking environmental monitoring with forms of citizen science. In majority of cases, they see it as a way to support the co-creation of relevant, context-specific knowledge to address the complex problems exemplified by the cases. The authors agree that the combination of longitudinal design and large numbers of observers – the key strengths of citizen science-based approaches – creates opportunities for ecological and agricultural research, improving data availability (increased sample sizes) and quality (real-time, GIS-referenced). For example, CitationAsingizwe et al. (2018) describes how a community-based mosquito surveillance system might improve the quality of data on the ecology of vector-carrying mosquitos and CitationChepkwony et al. (2018) argue that ICT-enabled real-time wildlife/livestock conflict monitoring may increase the accuracy and reliability of incidence reporting and response.

Apart from benefits to research, the authors in this Special Issue suggest that citizen science may offer new ways of sensitizing the stakeholders to particular environmental issues (benefits to society, see CitationLoss et al., 2015). Building on the assumption that participation in scientific research facilitates engagement and learning, citizen science provides new tools to generate and uphold public interest in matters of collective importance. As pointed out by CitationMurindahabi et al. (2018), such projects can realize significant social outreach, such as raising the collective awareness of malaria prevalence and prevention measures. CitationTafesse et al. (2018) and CitationMcCampbell et al. (2018) also argue that by combining research with public education, citizen science may help achieve broader societal impacts. Apart from informing the stakeholders about the cutting-edge developments in plant science such an approach is likely to result in more meaningful, locally actionable research, including effective ways of containing the epidemics. Similarly, the articles on agriculture and water management in Ghana (CitationNyadzi et al., 2018; CitationNyamekye et al., 2018) make plausible that community-based monitoring maybe usefully connected to science-based models and databases with hydro-climatic data.

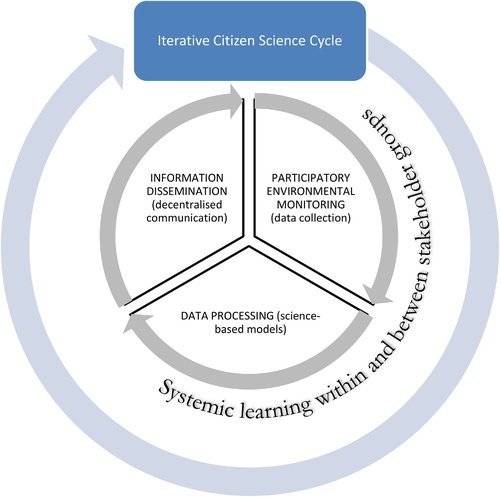

Our earlier observation that the environmental challenges that we are dealing with are characterized by a higher level of complexity than initially anticipated, further underpins our expectation that combining community-based environmental monitoring with citizen science approaches may be beneficial (see also CitationJalbert and Kinchy, 2016). This is because these approaches can help to place community level information in a broader context, both in terms of time and space, and can serve to enhance the credibility of locally generated information and insight in wider stakeholder networks. However, this collective, systemic learning capacity of the citizen science projects (CitationBela et al., 2016) remains relatively unexplored by the cases. Destined to last for extended periods of time, citizen science projects are often cyclical (i.e. annually or seasonally repeated); therefore, they allow for continuous revising of the relevance of the outputs achieved and the usability of the information generated (). As such, citizen science allows to move away from a linear model (problem – research – solution) and towards an iterative cycle that accommodates integration of various feedbacks and responses (CitationArmitage et al., 2008). After each cycle of data collection, analysis and communication, the project assumptions get to be re-evaluated from the point of view of both science (reliability, accuracy, originality) and society (usability, legitimacy, relevance) (CitationBela et al., 2016). Considering the unstable, evolving nature of the complex problems identified by the cases, each new cycle of citizen science brings up the opportunity to reassess the research question and desired outputs for maximized scientific and local relevance. As such, citizen science projects go beyond the planned acquisition and processing of data, focusing instead on incremental learning, flexibility and adaptation. This learning occurs at different scales or levels of the system, including the scientists themselves, but also the citizens, knowledge communities, organizations and institutions. As mentioned, these features are likely to make citizen science approaches especially relevant to the kinds of complex social and ecological challenges that we are dealing with.

Importantly, each one of the stages of the citizen science cycle may entail different forms and degrees of citizen engagement, depending on a range of contextual conditions, including the research questions asked and the attitudes of researchers. In , we distinguish between different forms of citizen engagement proposed in our case-studies, mapping it against the citizen science project classification of Muki CitationHaklay (2013).

Table 3 Citizen science research stages and their specifications.

Thus, we see that the contributors to this Special Issue position and conceptualize citizen science in meaningfully different ways. Taking the form of participatory community-based environmental monitoring, data collection is recognized as an efficient strategy of achieving both research objectives (e.g. new knowledge on tick ecology, CitationChepkwony et al. (2018)) and societal objectives (e.g. validating local knowledges, CitationNyadzi et al. (2018)) of the project. Engaging the citizens in the third stage (information, communication and dissemination) of the research cycle is also mentioned, with particular focus on informal networks (CitationMunthali et al., 2018) and non-hierarchical information flow (CitationDamtew et al., 2018). At the same time, the authors rarely touch upon engaging the citizens in the data analysis and interpretation stage, which is a weakness when the purpose is to foster systemic learning in complex settings.

In relation to the above, and along with CitationBela et al. (2016), we feel that future action research efforts in our program and beyond should become more oriented towards mobilizing citizen science to support systemic rather than only community-based learning, which implies broader and greater stakeholder involvement in interpretative discussion and exchange. As part of this, we may evaluate how different operationalizations of citizen science interact with contextual features, and shape learning processes and outcomes among interdependent stakeholders. While stakeholders may depend on each other in different ways, it is clear that the emergence of a certain degree of mutual trust is decisive for successful collaboration and collective action in stakeholder networks (CitationDe Vries et al., 2015). In the context of our project, it becomes therefore relevant to investigate how and when data collected, interpreted and shared through citizen science approaches are linked with dynamics of trust among stakeholders. How do initial conditions in terms of trust shape processes of data collection, data analysis and sharing, and vice versa? When and why do different stakeholders (e.g. community members, scientists and policy makers) trust or distrust the information generated through citizen science approaches? And how are such dynamics influenced by the nature of interdependencies among stakeholders or the approach to citizen science adopted? Such interactional questions about the relations between citizen science and trust formation go beyond the more classical –but still very relevant- question of whether or not data collected through citizen science approaches yield accurate and valid information (CitationSteinke et al., 2017). In the context of participatory crop variety selection, CitationSteinke et al. (2017) suggest indeed that low reliability of individual data points can be compensated by high numbers of observers, thus demonstrating usefulness of the ‘Wisdom of Crowds’ principle in agricultural research. It would be important to study if and how the availability or non-availability of such statistically robust studies influences systemic learning and policy change in our EVOCA cases and beyond.

3.5 Reflections on responsibility

The introductory paper to this Special Issue (CitationCieslik et al., 2018) warns for a naive optimism about EVOCA-type platforms, and indicates that novel ICT-uses may give rise to new forms of exclusion, inequality and power struggle, or that institutional environments may not be conducive to developing and maintaining citizen science applications. In order to foster greater recognition for such issues, the introductory paper suggests to pay attention to questions and principles derived from the responsible innovation framework in the process of designing EVOCAs. While several articles allude to responsible innovation, only one case-study (CitationNyamekye et al., 2018) explicitly considers the four dimensions of the framework: (a) anticipation of potential consequences of the innovation, (b) inclusion of all affected parties and viewpoints, (c) responsiveness to changing societal demands and concerns, and (d) reflexivity on values and assumptions underlying design choices.

Limited attention to anticipating negative consequences - A closer look at the articles in this Special Issue reveals that most cases pay attention to the ‘inclusion’ dimension in that they suggest a participatory mode of EVOCA development (CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018; CitationNyamekye et al., 2018; CitationNyadzi et al., 2018) and/or call for strong(er) user-orientation and feedback (CitationMurindahabi et al., 2018; CitationAsingizwe et al., 2018; CitationMunthali et al., 2018; CitationAgyekumhene et al., 2018). However, inclusion of people does not guarantee automatically that their relevant local knowledge and understanding are elicited and included as well; only two out of the six cases have explicitly progressed on this so far (CitationNyamekye et al., 2018; CitationNyadzi et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018). The other three dimensions, however, are far less consistently and explicitly addressed, even though there are several indications that this may be important. In relation to the anticipation of negative consequences, for example, it is reported in the case on tick-borne diseases that those pastoral herders without mobile phones already suffer from political and economic exclusion (CitationChepkwony et al., 2018; CitationMutavi et al., 2018). The same case suggests that mobile communication may have facilitated land invasions, leading to greater intensity of land-related conflicts. Similarly, the tailor-made service delivery case in Ghana suggests that differences in digital literacy may affect who benefits from extension messages or agricultural subsidies, and who does not. More in general, CitationMann (2018) urges scholars and practitioners to think about the future ‘political economy’ of African data. This is certainly relevant for us, as none of the cases has so far touched upon issues of who will control and own EVOCA data, how to avoid that external parties (e.g. ICT companies) become the custodians of African data, or how to safeguard privacy and prevent undesirable forms of surveillance (see CitationMann, 2018; CitationBronson and Knezevic, 2016). In all, further effort to anticipate unintended consequences of our efforts to develop EVOCAs is desirable.

Some reflexivity with significant blind spots - In connection with ‘responsiveness’, the water case-study signals that the time horizon of the EVOCA project may well be too short to enable this, and that taking user perspectives seriously may go at the cost of the whole idea of demonstrating the usefulness of EVOCAs. This points to significant risks and constraints in our own institutional environment (CitationNyamekye et al., 2018) that are largely ignored in other case-studies. In terms of ‘reflexivity’, the tick-borne diseases case questions the initial assumption on the basis of which the case-study was founded, namely the idea that tick-borne diseases are a priority issue. Other expressions that might be seen as evidence of reflexivity in our case-studies are the (self-)critical analysis link of the relevant institutional environment in the Ethiopian (CitationDamtew et al., 2018; CitationTafesse et al., 2018) and Ghanaian (CitationMunthali et al., 2018) innovation systems. While the latter case-study also points to challenges with regard to the sustainability of existing ICT platforms, such reflections are still markedly absent with regard to our own initiatives. Indeed, more explicit reflection is needed on how our initiatives can become embedded in a process that transcends the boundaries of four year PhD projects, and on the ownership and partnership arrangements needed for that.

In other contexts too, studies suggest that the underlying principles of responsible innovation do not receive sufficient attention, even in projects that espouse to such ideals (CitationBlok and Lemmens, 2015; CitationEastwood et al., 2017). In our case studies, the unbalanced attention for relevant dimensions of responsible innovation may relate to several factors. While the teams have been exposed to the idea of responsible innovation, they may have lacked practical experience and guidance on how to operationalise it in EVOCA research and design at such an early stage in their work. In relation to this, it is relevant to point out that the framework has so far been mostly used in relation to upstream technologies that emerge from fundamental science (e.g. biotechnology and nanotechnology), and has not yet been translated towards novel uses or variations of technologies that are already utilized broadly, such as mobile ICT platforms and applications. And finally, and perhaps most importantly for most cases, we have already signalled that the EVOCAs under consideration still lack clarity in terms of their technical, informational and social features. Discussing and anticipating the consequences of something that is still somewhat vague, and also composed of several non-technical components, is perhaps less easy than initially foreseen.

In all, the challenge for the future is to translate, adapt and apply responsible innovation principles in the next steps of designing EVOCA platforms, and simultaneously link these to efforts to foster ownership and sustainability. Our experiences in this regard will contribute to a broader debate on the ramifications of applying responsible innovation frameworks across cultures and in development settings, and on the simultaneous need to tailor the approach towards less capital intensive and radical technologies (e.g. conventional agricultural technologies and mobile phone applications) than those for which the framework was developed (CitationMacnaghten et al., 2014; CitationEastwood et al., 2017). Synthesizing lessons on the use of the framework in our case studies may be a contribution of the EVOCA programme to the further development of the theory and practice of responsible innovation and research in development settings. One practical way of advancing this could be to design and expand the ‘informational validation experiments’ that we called for in a previous paragraph in such a way, that they incorporate longer time horizons and attention to variables and dimensions that relate to equity, power, sustainability and control. In any case, particular attention will have to be paid to the possibility that the use of ICT platforms and applications may threaten privacy, enhance the control of international ICT companies over community data, or shift power balances between communities and higher level authorities (CitationMann, 2018; CitationEastwood et al., 2017). Another risk that must be anticipated is that model-based digital citizen science platforms may -through in-built assumptions and rationales that remain implicit- promote dominant (but questionable) directions of farm development that users are not aware of (CitationLeeuwis, 1993; CitationBronson and Knezevic, 2016).

4 Conclusion

Our interest in the potential of digital citizen science platforms (EVOCAs) to support collaboration in the management of environmental challenges was inspired in part by Ostrom’s research on community based governance of common resources. We expected that such platforms could help operationalize several design principles and community conditions that are known to enhance the capacity to address environmental challenges, and which are strongly related to communication capacity and information provision. Closer investigation of our case-studies through diagnostic studies, however, suggests that our collective action challenges are of a more complex nature than originally anticipated. The problems we are dealing with often cannot be resolved within clearly demarcated communities, since there appear too many dependencies with other communities and governance levels. Moreover, we found that the level of agreement on goals, means and responsibilities leaves to be desired, even in cases where there are overlapping problem definitions and relatively low levels of uncertainty in the system. In addition, our environmental challenges are characterized by a relatively high level of stability or inflexibility in the system, linked to dominant political cultures, bio-physical infrastructures, poverty and historical path dependencies. One such path dependency is that there is no recent history of effective community-based management of the common resource or public good on which communities can build. The reasons for this may vary (e.g. related to erosion of traditional authorities, increased central control, demographic changes, migration, newness of the threat or resource, etc.) but it is in any case a relevant note, especially since Ostrom’s design principles and community features were derived from situations where effective collective governance was indeed present. Establishing principles and conditions in situations where collective management is newly introduced is arguably a totally different ballgame, especially in situations with high levels of complexity. As we have seen, stakeholders in such situations may not even realize or perceive that they are faced with a collective action challenge and/or the idea that they depend on each other in order to maintain a common resource, create a public good or combat a public bad.

In view of the above, the diagnostic studies cannot confirm the plausibility of the assumptions made at the start. However, this does not render our interest in the potential of virtual citizen science platforms useless and trivial. First of all, we have seen that stakeholders’ awareness of mutual interdependencies and the collective nature of challenges can depend critically on the available knowledge and understanding of the agro-ecology and technical options, which implies that co-creation of knowledge and information remains highly relevant. In addition, all case studies have alluded to the existence of information gaps that can be resolved through decentralized data collection and environmental monitoring, and there is no reason to believe that enhanced communication capacity and connectivity become less relevant when the degree of complexity increases. Moreover, we have suggested that citizen science approaches may become even more relevant in complex settings, because they are well-positioned to fostering the kind of adaptive and systemic learning across stakeholder communities that is needed to address complex challenges.

In order to fully capture and assess the potential of EVOCAs, we have suggested several directions for further action and research. We have argued that greater precision and further validation is required with regard to the data and information that EVOCAs are supposed to collect and analyze in order to have societal impact, and that the use of games and choice experiments maybe a promising strategy in this regard. We have proposed a similar lab-in-the-field approach to shed further light on the hypothesis that ICT enhanced communication capability and connectivity can support cooperation within communities; this as a complement to our more qualitative and in-depth comparative case analysis. In addition, we have argued that we need to more systematically examine local knowledge and already existing and self-organized forms of ICT-use (instead of focusing on externally introduced packages or designs), and explore conducive task divisions between ‘old’ and ‘new’ media as components of EVOCAs. Another area that merits further investigation hinges on the interrelations between forms of citizen science, multi-stakeholder learning and dynamics of trust and distrust in diverging contexts. Finally, we concluded that we should pay more attention to several dimensions of responsible innovation during the EVOCA design trajectories, in order to explore possible unintended consequences and prevent undesirable effects regarding issues like equity, sustainability and control over data, information and development directions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding for the EVOCA program by the Wageningen University International Research and Education Fund (INREF) as well as financial contributions by The CGIAR Fund Donors (http://www.cgiar.org/about-us/our-funders/), received through ILRI, CIP, IITA, WUR and FARA. We also thank MDF and KITE for their financial contributions to research work in Ghana.

References

- Ch. Agyekumhene J.R. de Vries A. van Paassen P. Macnaghten M. Schut A. Bregt The role of ICTs in improving smallholder maize farming livelihoods: the mediation of trust in value chain financing NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- M. Arkesteijn B. van Mierlo C. Leeuwis The need for reflexive evaluation approaches in development cooperation Evaluation 21 1 2015 99 115

- D. Armitage M. Marschke R. Plummer Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning Glob. Environ. Chang. Part A 18 2008 86 98

- D. Asingizwe M. Poortvliet C.J.M. Koenraadt A.J.H. van Vliet M. Murindahabi Ch. Ingabire L. Mutesa P.H. Feindt Applying citizen science for malaria prevention in Rwanda: an integrated conceptual framework NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- S. Bates L. Scarlett Agricultural Conservation and Environmental Programs: The Challenge of Measuring PerformanceAvailable at:2013 AGree Washington, DC http://www.foodandagpolicy.org

- G. Bela T. Peltola J.C. Young B. Balázs I. Arpin G. Pataki Learning and the transformative potential of citizen science Conserv. Biol. 30 5 2016 990 999

- W.L. Bennett A. Segerberg The logic of connective action Inf. Commun. Soc. 15 5 2012 739 768

- F. Berkes J. Colding C. Folke Navigating Social-ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change 2003 Cambridge University Press Cambridge, United Kingdom

- E. Beza J. Steinke J. Van Etten P. Reidsma C. Fadda S. Mittra P. Mathur L. Kooistra What are the prospects for citizen science in agriculture? Evidence from three continents on motivation and mobile telephone use of resource-poor farmers PLoS One 12 5 2017e0175700https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175700

- V. Blok P. Lemmens The emerging concept of responsible innovation. Three reasons why it is questionable and calls for a radical transformation of the concept of innovation B.J. Koops I. Oosterlaken H. Romijn T. Swierstra J. van den Hoven Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches, and Applications 2015 Springer International Publishing Cham 19 35

- I. Brinkman J. Both M.E. De Bruijn The mobile phone and society in South Sudan: a critical historical-anthropological approach J. Afr. Media Stud. 9 2 2017 323 337

- K. Bronson I. Knezevic Big Data in food and agriculture Big Data Soc. 3 1 2016 1 5

- V.V.A. Brown J. Harris J. Russell Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination 2012 Earthscan London, UK

- R. Chepkwony S. van Bommel H.H.T. Prins F. van Langevelde Citizen science for development: the potential role of mobile phones in sharing of information on ticks and tick-borne diseases in semi-arid savannahs of Kenya NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- K. Cieslik C. Leeuwis A. Dewulf P. Feindt R. Lie S. Werners M. van Wessel P.C. Struik Addressing socio-ecological development challenges in the digital age: environmental virtual observatories for connective action NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- J. Conklin Wicked problems and social complexity J. Conklin Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems 2006 Wiley Hoboken, NJ 1 20

- E. Damtew S. Tafesse R. Lie B. van Mierlo B. Lemaga K. Sharma P.C. Struik C. Leeuwis Diagnosis of management of bacterial wilt and late blight in potato in Ethiopia: a systems thinking perspective NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- M.E. De Bruijn R. Van Dijk Connecting and change in African societies: examples of’ ethnographies of linking’ in anthropology Anthropologica 54 2012 45 59

- M.E. De Bruijn A. Amadou E. Lewa Doksala B. Sangaré Mobile pastoralists in Central and West Africa: between conflict, mobile telephony and (im)mobility Rev. Sci. Tech. 35 2 2016 649 657

- J.R. De Vries N. Aarts A.M. Lokhorst R. Beunen J. Oude Munnink Trust related dynamics in contested land use a longitudinal study towards trust and distrust in intergroup conflicts in the Baviaanskloof, South Africa For. Policy Econ. 50 2015 302 310

- K. Dehnen-Schmutz G.L. Foster L. Owen S. Persello Exploring the role of smartphone technology for citizen science in agriculture Agron. Sustain. Dev. 36 25 2016 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0359-9

- C. Eastwood L. Klerkx M. Ayre B. Dela Rue Managing socio-ethical challenges in the development of smart farming: from a fragmented to a comprehensive approach for responsible research and innovation J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2017 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-017-9704-5in press

- J. Fischer Ta. Gardner E.M. Bennett P. Balvanera R. Biggs S. Carpenter Advancing sustainability through mainstreaming a social-ecological systems perspective Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 14 2015 144 149

- T. Foran J.R.A. Butler L.J. Williams W.J. Wanjura A. Hall L. Carter P.S. Carberry Taking complexity in food systems seriously: an interdisciplinary analysis World Dev. 61 2014 85 101

- S.O. Funtowicz J. Ravetz Science for the post-normal age Futures 25 7 1993 739 755

- O. Gloede L. Menkhoff H. Waibel Shocks, individual risk attitude, and vulnerability to poverty among rural households in Thailand and Vietnam World Dev. 71 2013 54 78

- M. Haklay Citizen science and volunteered geographic information – overview and typology of participation D.Z. Sui S. Elwood M.F. Goodchild Crowdsourcing Geographic Knowledge: Volunteered Geographic Information (VGI) in Theory and Practice 2013 Springer Berlin 105 122

- G.W. Harrison J.A. List Field experiments J. Econ. Lit. 42 4 2004 1009 1055

- M. Hisschemoller R. Hoppe Coping with intract- able controversies: the case for problem structuring in policy design and analysis Knowledge and Policy 8 4 1996 40 60

- K. Jalbert A.J. Kinchy Sense and influence: environmental monitoring tools and the power of citizen science J. Environ. Policy Plan. 18 3 2016 379 397

- S. Jasanoff The Fifth Branch: Science Advisers as Policymakers 1990 Harvard University Press Cambridge, MA

- H. Jenkins Convergence culture Where Old and New Media Collide 2006 New York University Press New York and London

- M. Jerven Poor Numbers. How We Are Misled by African Development Statistics and What to Do About It 2013 Cornell University Press Ithaca, NY

- T. Karpouzoglou Z. Zulkafli S. Grainger A. Dewulf W. Buytaert D.M. Hannah Environmental Virtual Observatories (EVOs): prospects for knowledge co-creation and resilience in the information Age Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 18 2015 40 48 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.07.015

- C. Leeuwis Of computers, myths and modelling: the social construction of diversity, knowledge, information and communication technologies in Dutch horticulture and agricultural extension Wageningen Studies in Sociology, Nr.36 1993 Wageningen Agricultural University Wageningen

- K. Levin B. Cashore S. Bernstein G. Auld Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change Policy Sci. 45 2 2012 123 152

- S.R. Loss S.S. Loss T. Will P.P. Marra Linking place-based citizen science with large-scale conservation research: a case study of bird-building collisions and the role of professional scientists Biol. Conserv. 184 2015 439 445

- P. Macnaghten R. Owen J. Stilgoe B. Wynne A. Azevedo A. de Campos J. Chilvers R. Dagnino G. di Giulio E. Frow B. Garvey C. Groves S. Hartley M. Knobel E. Kobayashi M. Lehtonen J. Lezaun L. Mello M. Monteiro J. Pamplona da Costa C. Rigolin B. Rondani M. Staykova R. Taddei C. Till D. Tyfield S. Wilford L. Velho Responsible innovation across borders: tensions, paradoxes and possibilities J. Responsible Innov. 1 2 2014 191 199 https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2014.922249

- L. Mann Left to other peoples’ devices? A political economy perspective on the big data revolution in development Dev. Change 49 1 2018 3 36

- V.C. Materia F. Giarè L. Klerkx Increasing knowledge flows between the agricultural research and advisory system in Italy: combining virtual and non-virtual interaction in communities of practice J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 21 3 2015 203 218

- M. McCampbell M. Schut I. Van den Bergh B. van Schagen B. Vanlauwe G. Blomme S. Gaidashova E. Njukwe C. Leeuwis Xanthomonas Wilt of Banana (BXW) in Central Africa: opportunities, challenges, and pathways for citizen science and ICT-based control and prevention strategies NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- M. Milinski R.D. Sommerfeld H.J. Krambeck F.A. Reed J. Marotzke The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. PNAS 105 7 2008 2291 2294

- A. Moore Beyond participation: opening up political theory in STS Soc. Stud. Sci. 40 2010 793 799

- N. Munthali C. Leeuwis A. van Paassen R. Lie R. Asare R. van Lammeren M. Schut Innovation intermediation in a digital age: comparing public and private ICT platforms for agricultural extension in Ghana NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- M. Murindahabi D. Asingizwe P.M. Poortvliet A.J.H. van Vliet E. Hakizimana L. Mutesa W. Takken C.J.M. Koenraadt A community-based malaria mosquito surveillance approach in Ruhuha, Rwanda NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- F. Mutavi I. Heitkönig A. van Paassen B. Wieland N. Aarts Tick management practices from a metis perspective NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- G.W. Ngaruiya J. Scheffran Actors and networks in resource conflict resolution under climate change in rural Kenya Earth Syst. Dyn. 7 2 2016 441 452

- B.G. Norton The ways of wickedness: analyzing messiness with messy tools J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 25 4 2012 447 465

- E. Nyadzi B.A. Nyamekye S.E. Werners A. Dewulf G.R. Biesbroek L. Fulco E. Van Slobbe P.L. Hoang C. Termeer Hydroclimatic environmental virtual observatory for connective action in rice farming systems in Ghana NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- A.B. Nyamekye A. Dewulf E. Van Slobbe K. Termeer C. Pinto The potential of hydro-climatic Environmental Virtual Observatory (EVO) to improving adaptive decision-making in rice production systems in Northern Ghana NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018

- E. Ostrom Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action 1990 Cambridge University Press Cambridge

- E. Ostrom Beyond markets and States: polycentric governance of complex economic systemsPrize Lecture, December 8, 2009Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47408, and Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, U.S.A. 2009

- E. Ostrom R. Gardner J. Walker Rules, Games, and Common-Pool Resources 1994 University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor

- A. Poteete M. Janssen E. Ostrom Working Together: Collective Action, the Commons, and Multiple Methods in Practice 2010 Princeton University Press Princeton NJ

- J.C. Scott Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed 1998 Yale University Press New Haven, CT

- Local governance in developing countries A. Shah Public Sector Governance and Accountability Series 2006 The World Bank Washington DC

- J. Steinke J. van Etten P.M. Zelan The accuracy of farmer-generated data in an agricultural citizen science methodology Agron. Sustain. Dev. 37 2017 32

- T.M. Stevens N. Aarts C.J.A.M. Termeer A. Dewulf Social media as a new playing field for the governance of agro-food sustainability Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 18 2016 99 106

- V.R. Sulaiman A. Hall N.J. Kalaivani K. Dorai T.S.V. Reddy Necessary, but not sufficient: critiquing the role of information and communication technology in putting knowledge into use J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 18 4 2012 331 346

- S. Tafesse E. Damtew B. van Mierlo R. Lie B. Lemaga K. Sharma C. Leeuwis P.C. Struik Farmers’ knowledge and practices of potato disease management in Ethiopia NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2018