Abstract

Drawing from a social capital perspective, this paper explores sources of organisational resilience within a public–private partnership. Responding to persistent poor performance the UK Highways Agency, responsible for maintaining and developing the national road infrastructure introduced a collaborative approach to supplier management and engagement. Drawing from a case study of the Construction Management Framework (CMF), it is argued that the development of structural, cognitive and relational elements of social capital provides a fertile context for the emergence of organisational resilience. The CMF achieved significant performance improvement, adapting itself to the changing needs of the Highways Agency, and found ways to capture and use innovation, and provides an example of effective Business Continuity Management (BCM) practice in identifying and responding to threats and in building organisational resilience, safeguarding the interests of key stakeholders and value-creating activities.

1 Introduction

Success is often transient, as illustrated in CitationMiller's (1990) exploration of the so called Icarus Paradox in which the roots of failure emerge from the hubris often associated with sustained success. Recognition of the threat of failure, for even successful organisations, has contributed to the emergence of crisis management as a field of inquiry. For the public sector this interest in crisis management has had a variety of drivers. At one level this reflects the important role played by the public sector in preparing for and responding to crisis (see for example, CitationBoin, ‘tHart, Stern, & Sundelius, 2005). More specifically, legislation, audits, increasing public–private partnership working and a plethora of crisis events have all added to the impetus to develop a crisis management capability (CitationDrennan & McConnell, 2007). For the sake of legitimacy there is often an expectation that such a capability be accredited externally, such as by the Business Continuity Management (BCM) standard BS25999 (CitationElliott & Johnson, 2010).

Early studies of crisis management emerged from the field of disaster response (CitationSmith, 2006) with the focus of research and practice, upon how to respond better to natural disasters. The growing awareness that vulnerability to crisis might be incubated from within triggered a switch in emphasis towards better understanding those conditions that may make an organisation more prone to crisis or less resilient to their effects (CitationPauchant & Mitroff, 1988, 1992; Shrivastava, 1987; Turner, 1976). A growing literature has considered processes around organisational learning for and from crisis (CitationBoin, 2008; Smith & Elliott, 2007). More recently, the focus has shifted towards how the pre-crisis capabilities of organisations may be harnessed to develop resilience (CitationComfort, Boin, & Demchak, 2010; Elliott & Johnson, 2010).

The purpose of this paper is to explore how pre-crisis capabilities and resilience (core to Business Continuity Management) may be developed through inter-organisational cooperation, a topic which has received recent, if limited attention (for example, CitationSvedin, 2009). However, in one short article there is a limit to comprehensiveness and the focus here is on one particular case of a public–private partnership building social capital in order to ‘organise’ for effective Business Continuity Management. Public–private partnerships have been identified as posing particular difficulties in organising given the different ‘habits and cultures’ of the different sectors (CitationBranscomb & Michel-Kerjan, 2006). This paper explores the efforts of the UK Highways Agency (HA) to build a collaborative network of construction firms. Identifying an underdeveloped area in the knowledge base within organisation studies, the paper links together concepts drawn from the study of social capital and organisational resilience and considers how interconnectedness and interdependence may be harnessed to develop resilience by enhancing the capacity to anticipate and respond to incidents. The paper begins by providing an overview of Business Continuity Management, a practice increasingly adopted by the public sector within the UK, encouraged in part by the inclusion of recommendations from public inquiries that organisations should seek to meet the requirements of the standards set out in BS25999 (see CitationPitt (2008) for example). It then provides succinct reviews of organisational resilience and social capital and develops a conceptual map for considering the focal case study. Finally, the implications for policy makers are discussed with regard to how policy lessons may be translated into new practices.

2 Business Continuity Management

As a practice, BCM has evolved from disaster recovery and a focus upon mainframe computers to a discipline concerned with developing the capability to protect key business processes and to respond effectively to business interruptions and crises (CitationElliott, Swartz, & Herbane, 2002). It has been defined as a:

“holistic management process that identifies potential threats to an organisation and the impacts to business operations those threats, if realized, might cause, and which provides a framework for building organisational resilience with the capability for an effective response that safeguards the interests of its key stakeholders, reputation, brand and value-creating activities” [CitationBSi, 2006]

Audit has played an important role in driving organisational investment in BCM activity since the early 1990s (CitationElliott et al., 2002). This has been particularly marked in the UK, especially since the publication of BSi25999. CitationElliott and Johnson's (2010) study reported that BCM retained a persistent emphasis upon developing contingency measures for hard systems, an approach that lent itself, readily, to audit. Notwithstanding the important role played by audit and standards in the diffusion of business continuity practice the potential limitations of such an approach were illustrated by the failure of public sector body to respond effectively to a disaster despite having won awards for its practice. Considered an exemplar of good practice, Gloucestershire County Council (GCC) was awarded ‘Beacon Status’ for its BCM processes in March 2007 and received funding to help it share its expertise with other government agencies (CitationElliott & Macpherson, 2010). Four months later, in July 2007, following the worst summertime floods in 60 years, Gloucestershire's business continuity plans and processes were found to be seriously flawed. For example, despite the appearance of proper systems and processes, single points of failure in electricity and water supplies had not been identified resulting in the loss of power to thousands of homes and businesses (CitationPitt, 2008). The Council's own emergency management center was located in a bunker that was already prone to flooding (CitationGarnham, 2007). These failures might be seen as elementary and suggest that an effective business continuity capability is not easily measured or evaluated, particularly in a paper based assessment. Gloucestershire County Council's fiasco highlighted the possible limitations of evaluating success with regard to highly tangible elements only. The evaluation of a ‘successful’ crisis or Business Continuity Management capability may require an approach incorporating less quantifiable elements. For example, CitationLengnick-Hall and Beck (2005) writing on the rapid recovery of a Sandler O’Neill and partners, following the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, described resilience as a transformational capability. Drawing from its social capital, with a reputation as a ‘relationships firm’, Sandler O’Neill re-engaged many retired staff and ex-workers. The company resumed trading a week afterwards and was making record profits and revenues within a year (CitationFreeman, Hirschhorn, & Maltz, 2004). The firm's social capital, alongside plans and processes, played a pivotal role in this quick turnaround; the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. In building on conceptions of business continuity practice as a management system this paper explores the role of social capital as a potential source of organisational resilience.

3 Resilience and social capital

Perspectives from different disciplines suggest some difference of opinion regarding the meaning of resilience and how it is operationally defined. Broadly, resilience can be characterized in a number of ways; as ‘emotional’, which considers resilience as a character trait in a person, organisation, or community; ‘engineering’, which considers resilience as a systemic attribute that allows the system to return to its original state as quickly as possible; and ‘ecological’, which considers the return to a new stable regime through learning and adaptation. In order to deal with complexity, scholars from different disciplines have argued systems should be characterized by a combination of these types (Citationde Bruijne, Boin, & van Eeten, 2010, p. 30). Tensions within and across disciplines pertain to the idea of ‘bouncing back’, whether this is achieved through anticipatory measures such as planning or through an ability to react to unexpected disturbance. A second tension questions whether the idea of ‘bouncing back’, means restoring prior order or creating something new or different. A third tension concerns the nature of events to which resilience can be applied; whether these should be restricted to major events or include routine disturbances (Citationde Bruijne et al., 2010, p. 31).

Organisation studies exhibit a tension between equilibrium seeking and renewal focused perspectives of resilience. CitationWildavsky (1988) described resilience as the ability to bounce back, reflecting CitationMeyer's (1982) study of how hospitals adapted to an unexpected doctors’ strike, absorbing a discrete environmental shock and restoring prior order. The case of Sandler O’Neill outlined above shows resilience as an emergent capability, one that is built over time. CitationSutcliffe and Vogus (2003) suggest that an organisation not only survives by positively adjusting to current adversity, but also through this process of responding, strengthens its capability to make future adjustments. “Resilience is not just a reactionary phenomena, it emerges from relatively ordinary adaptive processes that promote competence, restore efficacy, and encourage growth, as well as the structures and practices that bring about these processes” (CitationSutcliffe & Vogus, 2003, p. 95). The notion of resilience has appeared in the official definition of BCM relatively recently, reflecting the trend towards developing pre-crisis capabilities identified earlier.

There is no unified definition for organisational resilience; it appears on the one hand to be an ability to absorb shocks and restore prior order, the other hand an ability to positively adapt to change and transform experiences or situations to advantage. CitationWeick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld (1999) capture both perspectives in their resilience interpretation – ‘maintenance of positive adjustment under challenging conditions’.

3.1 Managing the resilience ‘trade-off’

Recognising the inherent tension in the resilience construct, scholars have identified the need for ‘trade-offs’ in building resilience. CitationSutcliffe and Vogus (2003) argue positive adaptation over the long term, which they interpret as resilience, requires managing a trade-off between ‘growing’ (enhancing variation, innovation) and ‘building competence’ (efficiency, honing existing competencies). CitationMarch (1991) noted a concern of studies of adaptive processes is the relation between the exploration of new possibilities and the exploitation of old certainties. Similarly, CitationRobb (2000) depicts a resilient organisation as a hybrid entity with an ability to sustain competitive advantage comprising two integrated domains of activity. A ‘performance system’ capable of delivering excellent performance against current goals, and an ‘adaptive system’ enabling the organisation to effectively innovate and adapt to rapid, turbulent changes in markets and technologies. An organisation that is overly performance-driven towards current goals can become rigid when faced with unanticipated events or change. An organisation that is overly adaptation-driven may be rich in creativity, and improvisation, but may have difficulty in forming the structures necessary to deliver consistent, repeatable, excellent performance. Although well drilled in crisis management, a top brand hotel chain failed to deal effectively with an outbreak of food poisoning in several of their facilities. Staff implemented the crisis management plan, and in this regard the ‘performance system’ functioned well. However, as the crisis evolved the organisation was unable to produce the necessary adaptations to meet changing circumstances not anticipated in the plan. In this regard the ‘adaptation system’ failed. Substantial amounts of money were paid in compensations to avoid legal action from guests and tour operators and the reputation of the hotel chain a received a major blow (CitationParaskevas, 2006).

3.2 Measuring resilience

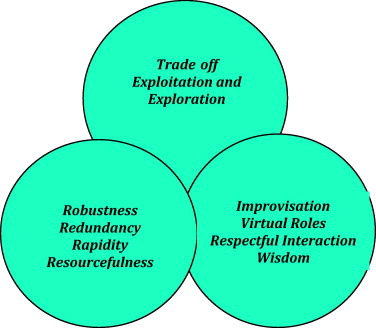

With no unified definition, attempts to measure or evaluate resilience remain problematic. CitationKendra and Wachtendorf (2003) identified four interrelated dimensions along which resilience might be measured. These are robustness – the ability to withstand or rebound from stress, redundancy – the extent to which elements are substitutable, rapidity – the capacity to meet priorities and achieve goals in a timely manner in order to contain losses and avoid future disruption, and resourcefulness.

In his study of team resilience, or its absence, in fighting a forest fire in Mann Gulch, CitationWeick (1993) identified four potential sources of resilience. First, the capacity to problem solve creatively through improvisation and bricolage. Second, virtual roles – the ability of members of a team to picture and comprehend the entire system of which they are a part, as a basis for filling in if another member is absent. Third, Weick identified an attitude of wisdom, which has the capacity to question what is known, to appreciate the limits of knowledge and to seek new information as appropriate. A fourth element concerned the notion of respectful interaction, of valuing of the reports of others and communicating honestly with them. For CitationWeick (1993) the presence of these sources creates a real potential for maintaining positive adjustment under challenging conditions, whether the focus is upon a crisis incident or dealing with the messiness and uncertainties of day-to-day organisational and community working.

Conversely the absence of these elements makes resilience unlikely. For example, arguably Weick's best known example of improvisation and bricolage is of a forest fire ranger using an escape fire to save himself in Mann Gulch. The ranger's colleagues failed to follow his example and many perished as a result. For Weick the Mann Gulch firefighters were a collection of individuals rather than a team and, although Weick does not use this term, there was an absence of social capital which, if present, might have enabled mutual trust, better communication and a sense of the group as an entity rather than quite literally every man for himself.

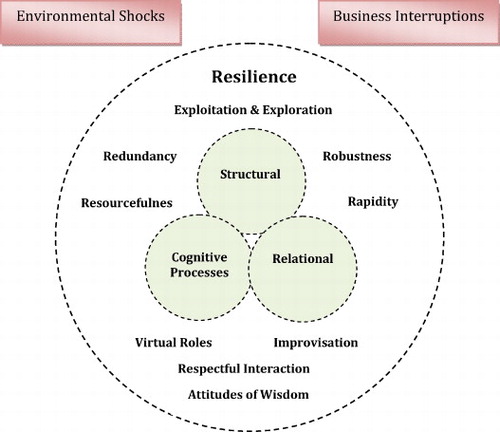

From our review, we identify CitationWeick et al.’s (1999) interpretation of ‘maintenance of positive adjustment under challenging conditions’ as a working definition of resilience for this paper. As a framework of analysis ( ), CitationMarch's (1991) relation between exploitation and exploration suitably captures the need for various ‘trade-offs’ within the resilience construct. Although there are no unified measures for resilience, the measures and potential sources identified by CitationKendra and Wachtendorf (2003) and CitationWeick (1993), respectively, provide useful dimensions for evaluation as key inputs or conditions for resilience.

3.3 Social capital

In the broader disaster management field, research has shown social capital to be a key component in a community's coping ability following natural and man-made hazards (CitationBuckland and Rahman, 1999; Murphy, 2007). Although social capital has generated interest in the context of ‘place based’ community resilience, there appears to be limited research that explores the role of social capital in building resilience in organisational or business community contexts.

A growing concern with shifting the emphasis of crisis and disaster management from the protection of essential infrastructure towards the formation of community resilience may be seen in CitationMurphy's (2007) account of a water contamination crisis in Walkerton (Canada) in 2000, where a local community assembled to design and implement an emergency water distribution system following domestic water contamination. Similar observations may be made in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (CitationO’Rourke, 2007, p. 25). There is a view that policy has moved from simply providing and organising rescue services towards developing the capacity of communities to respond to extreme events, recognising potential rich and local knowledge they possess. Within such a context a study exploring social capital for building resilience in an organisational community context makes a potentially valuable contribution. However, our concern here is not with a full review of the social capital literature but with how notions of social capital might inform the development and maintenance of organisational resilience.

Social capital has been defined as an asset that inheres in social relations and networks (CitationLeana & van Buren, 1999); understood roughly as the good will that is engendered by the fabric of social relations and that can be mobilised to facilitate action (CitationAdler & Kwon, 2002). For CitationColeman (1988), social capital is less tangible than other forms of capital (financial, physical and human). Coleman identified three forms of social capital. First, were obligations and expectations, which depend upon the trustworthiness of the social environment. Second, was the capacity for information to flow through the social structure and the third, concerned norms and sanctions. Two types of social structure were viewed as especially important in facilitating social capital. The first is of closure in the social network, so that all actors are connected in a way that obligations or other sanctions may be imposed upon its members. Closure does not necessarily need to be formal but can include the unwritten rules embedded within a social context. The second, Coleman describes as appropriable organisation in which the organisation created for one purpose may provide a source of valuable resources for different purposes. CitationPutman (1993) found that patterns of social interaction can help explain why some communities function much more effectively than others. Investigating Italian regional governments he found that in successful regions citizens are engaged by public issues and that social and political networks are organised horizontally rather than hierarchically. In successful regions people trust each other to act lawfully, and ‘civic communities’ value solidarity, participation and integrity. Putnam refers to social capital as features of social organisation such as networks, norms, and trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit.

Definitions of social capital vary according to whether the focus is on the substance, sources, or effects; whether the focus is primarily on the relationship an actor maintains with other actors (reflecting internal bonds) or the structure of relations among actors within a collective (reflecting external bridges), or both types of linkages (CitationAdler & Kwon, 2002, p. 19). CitationSchuller (2007) suggests bonding social capital refers to links with others who are broadly similar in kind; bridging social capital refers to the links a community has with others that are different, to whatever degree. Social network configurations have been considered in terms of vertical and horizontal links. The link between the state and society has been referred to as vertical, whilst horizontal links refer to the links that span group, community, or organisational boundaries (CitationAdger, 2003).

Our concern with social capital is with the notion that networks of social relationships possess the potential for collective action that might not have been possible without them. However, social capital is contested on several grounds. For example, it refers to characteristics of trust and neighbourliness that are difficult to quantify (CitationESRC, 2007) and may give rise to negative as well as positive externalities. Both the Ku Klux Klan and the Mafia achieve co-operative ends on the basis of shared norms, and therefore have social capital, but they also produce abundant negative externalities for the society in which they are embedded (CitationFukuyama, 2001). One tension within the literature is whether social capital represents a public or private good. Another is how the implicit advantage of social capital is harnessed. For CitationColeman (1988) this is via cohesive social structures. For CitationBurt (2005) advantage is brokered across structural holes in social structures. CitationGargiulo and Benassi (2000) propose rather than hoping to find an ideal balance between cohesive networks and structural holes, scholars should fully assume the existence of a trade-off that is inherent to the dynamic of social structures and investigate how successful individuals and organisations actually deal with the trade-off.

CitationNahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) identified three dimensions of social capital – structural, cognitive and relational. The structural dimension concerns the shape of networks in terms of ties and configurations. Shared codes, language and narratives provide the cognitive dimension by which actors represent themselves and interpret communications and information. The relational dimension refers to trust, norms, obligations and identity and may be considered as the personal aspects of network relations. Drawing from CitationNahapiet and Ghoshal's (1998) three dimensions this paper considers how the structures, cognitive processes and relationships within the Construction Management Framework provided a fertile context for the emergence of resilience as shown in .

4 Methods

The study of this public–private partnership emerged alongside a related, multi-sector inquiry into BCM practice across UK organisations. It appeared that many of the aspirations of the BSI definition of BCM were met through this example of exploiting social capital for organisational resilience. Where the starting point for most studies has been a retrospective analysis of learning after crisis, this paper focuses upon an existing network of contractors working for the Highways Agency (HA); a community of organisations which appeared to have achieved some degree of resilience.

Primary data were collected over a four month period. Adopting an ethnographic approach, data collection involved semi structured interviews and participant observation. Respondents, best described as manager/engineer practitioners from eleven community members and seven supply chain partners were interviewed, with an average duration of 90 min. Rather than pose detailed questions, participants were invited to talk about the benefits of being part of the community and differences between the CMF and traditional contract frameworks. Many stories with deep contextual meaning and examples of various forms of positive adjustment emerged from this approach.

Participants were observed during six fortnightly, on-site progress meetings. These were typically 3 h long. Attendees included managerial and supervisory staff from each of the four specialist contractors involved, from various departments of a managing agent contractor, including scheme designers, and from the Highways Agency.

Grounded theory (CitationCorbin & Strauss, 1990) was employed in the development of theory. The approach was guided by CitationEasterby-Smith, Thorpe, and Lowe's (1991) seven stage interpretation of grounded theory, albeit the process proved to be an iterative one. Data were revisited within 24 h of their capture as part of a reflective process and to validate initial thoughts. Transcriptions and field notes were re-read a number of times. Different analytical techniques were used during the various stages of the research; a notion supported by CitationEasterby-Smith et al. (1991) who suggest qualitative research is about ‘feel’ rather than systematic process. For example, one analytic technique is ‘looking at language’. Contractors referring to the CMF community as family implied strong identification and a cohesive social structure. Looking at language was a useful technique that generated further inquiry. The flip-flop technique was another useful means of analysis. For example, posing reflective questions such as, what would happen if contractors were unwilling to share resources or what motivates resource sharing? Using the flip-flop technique helped to expose the nature of network ties that could be exploited for mutual benefit and building resilience. Many sub-concepts appeared in more than one category. Through a messy process, codes were re-assessed, collapsed or expanded as appropriate for best location in building themes. Memos attached to coded data highlighted possible links between social capital and resilience constructs. In line with CitationGlaser and Strauss (1967), the approach involved standing back and asking broad questions such as ‘what is going on here?’ Through this reflection, the deeper common themes that seemed to explain how social capital was, or could be exploited for resilience emerged.

5 Case study background

From the initial interview it became apparent that this network appeared to have achieved some degree of resilience in that it possessed an ability to respond quickly and prevent the escalation of business interruptions. The Highways Agency (HA) had employed this approach as a response to the poor financial and productivity performance of previous contract management arrangements. Prior to this, contracts for highway maintenance had been awarded solely on the lowest price tender which met the specification. Outturn project costs were typically 40% above the original tender (CitationAnsell, Evans, Holmes, Price, & Pasquire, 2009). The new approach was part of a response to CitationEgan's (1998) ‘Rethinking Construction’, which sought improved delivery of maintenance and improvement schemes, and was labeled the Construction Management Framework (CMF).

The CMF differed from traditional contract tendering in several ways. Project designers, a managing agent contractor (MAC), and first tier contractors (known as specialist contractors) have a contractual relationship directly with the HA. Rather than tendering for individual projects, contractors tender for, and agree work prices with the HA for the duration of the fixed term framework. As the framework has matured a derived pricing system has developed. A MAC coordinates the project and in this respect they resemble a traditional principal contractor, but in the CMF the MAC, project designer, and specialist contractors are of equal status and share the same incentives to deliver a scheme on time and within budget. If they achieve this the whole community shares the rewards or, the costs if they fail. Each community member contributes to funding a Community Management Team which monitors performance, identifies areas for improvement, and promotes initiatives to share better practices. In addition, forming no part of any contractual agreement, members are expected to participate in certain initiatives developed by the community to enhance performance. Participation and success seems to be motivated by the community's espoused values, shared goals, and by peer pressure.

6 Social capital and resilience within the CMF

From the earlier literature review three dimensions of social capital were identified as potentially contributing towards resilience, namely, structure, cognitive processes and relationships (CitationNahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998).

6.1 Structural arrangements

The CMF established structural arrangements with the early involvement of all contractors as a first step in building community linkages. One specialist contractor (r10) identified the importance of such early participation, with members encouraged to review the project and suggest alternative combinations of resources, thereby creating a repertoire of responses for a range of situations. A range of additional structural forms were developed to encourage ongoing communication, reflection and innovation. For example, ‘Off-line’ groups enabled the development and sharing of resources and practices. Convened away from project delivery, three main groups, namely, process, culture, and measurement were supported by sub-groups including safety, innovation, and supply chain integration. Simple mechanisms, such as the co-location of contractors and ‘buddy partnering’ encouraged the sharing of ideas and better practices.

“I used to sit down with the other civil guy and we used to go through things and he used to tell us where he was having difficulties and likewise”. (r6)

Underpinning these mechanisms was the notion of equal voice, especially important for those normally considered as the second and third tier contractors. Peer pressure fed into ongoing performance review and 360° feedback sessions. Although a strong tie existed in the contract there was an expectation that members would voluntarily participate in activities for the benefit of the community. Despite weaker ties with sub-contractors there was evidence that the CMF approach extended beyond those with contracts:

“We have to manage the interfaces of our sub contractors and there are a few key ones that are absolutely crucial to it who are involved and fully understand how we price and they price, how we get paid and how they get paid. They’re very clear on that so you could argue that the CMF does go one tier below us”. (r11)

This was not always the case as one respondent indicated:

“I don’t go to the site meetings. I’m not invited. No. I’ve never been to a progress meeting… I’ve seen not one tangible example of inter supply cooperation in 9 years”. (r8)

In summary, the CMF's structural arrangements facilitated resource and information sharing, shared understanding, which together provided the enabling conditions for resilience in terms of robustness, rapidity and resourcefulness CitationKendra and Wachtendorf (2003). This was supported by the community's management team in their role as a communications hub, as promoters of continuous improvements and helping maintain a community wide understanding. This shared understanding helped foster the potential for supporting or assuming the role of any member experiencing difficulties, identified as one source of organisational resilience (CitationWeick, 1993), and a degree of redundancy identified as a dimension along which resilience can be measured (CitationKendra & Wachtendorf, 2003). Alongside strong contractual ties there were weaker ones which also enabled the adaptability that is core to many definitions of resilience. The data indicated that not all members conformed to the ideal but that a significant development from previous arrangements had been achieved.

6.2 Cognitive processes

The early involvement of contractors began with a facilitated workshop to elucidate community values and designed to challenge the adversarial approach typical of the construction industry.

“… we picked 20 contractors… None had got a clue what CMF was. And the very first workshop we scribbled up this thing called ‘joining the community’. … they all came and all we talked about was establishing our values. For a whole day we did nothing but establish boundaries… to own this stuff” (r9)

The three building blocks of process, culture, and measurement, were agreed as foundations for the CMF concept. These related to what they do, how it was done and how they proved it. Within the adversarial approach compliance with the formal contract or securing the necessary paperwork to record any amendments was central. Adapting to the CMF way was not easy.

“I’m here specifically to look after the CMF jobs… I came from *** who’ve always been renowned as being very contractual. And it took me a good 6 months to (1) buy into it, to say this does work rather than say it's all flowery, trust etc and (2) get my head around not having to go with a piece of paper to the site manager and say we want to do this, we want to do that. It's all about mindsets. And the other side of it is, when I came out of CMF and went on to a traditional contract, it was getting my head back into I do need to push this piece of paper in front of someone. They are completely different”. (r10)

Selecting appropriate people to work in the CMF was identified:

“We’ve got some fantastic people that work for our company but you couldn’t have them on this. They’re too abrupt or abrasive. Good at what they do but they’re not for partnering”. (r6)

Recurring terms within the data, such as ‘family’ or ‘no us and them’ suggested a strong alignment within the community. Labeling contractors as specialists and sub-contractors as supply chain partners denoted a different style of relations than previously held. The notion of partnership and working together were captured in a variety of posters contrasting, for example, two boxers with a team of rowers working in unison.

Respondents recounted stories illustrating the shift away from the previous adversarial relationship, ones which highlighted cooperation and resource sharing versus the individualism and competitiveness of previous arrangements. These tales described how cooperation had established better methods and saved money or recalled how competitors, had as community members helped each other out with no immediate payback, other than achieving the group's goals.

6.3 Relationships

The relational dimension of social capital was evident in many ways. For example, trust was observed in resource sharing, of both equipment and expertise, and reciprocity was observed at the individual level, as identified earlier. Three community members, competitors outside the framework, shared resources resulting in positive adjustment to a challenging condition:

“We were working for r10 on one side of the M6 and r18 was working on a separate scheme …about two miles to the south. The plant, a machine, hired to r10 broke down. We went onto the r18 scheme and transported plant on loan from r18 (competitors) to r10 to enable them to complete the nights work. It involved three parties agreeing to enable the work to be completed”. (r14)

The example suggests robustness, and is achieved through community redundancy and resourcefulness – dimensions along which resilience can be evaluated (CitationKendra & Wachtendorf, 2003).

Another specialist reported passing on an innovative solution to a problem, one developed at some cost, to a ‘competitor’ encountering a similar difficulty. They noted that on other contracts they might not even have been aware of the competitor's difficulty and would have been unlikely to offer assistance if they had (r18):

“That's something that's slightly strange and you have to get used to it. If you’re going to commit to the CMF, …We do quite regularly, sit openly sharing information with people that we would normally consider to be a competitor” (r4)

Although respondents indicated a high degree of trust compared to other projects, as the CMF neared full term, members became uncomfortable about information sharing (willingness to be vulnerable to another party) as there was uncertainty as to whether membership on the next framework will be secured.

“The client wants us to release some documentation from this framework to go into the tender documentation for the next framework and some of our specialists are a little concerned that that's putting some of their competitors in a better position when re-tendering”. (r3)

Resource exchanges may impose an expectation for reciprocation which within a community becomes a norm. For example, one specialist observed an ill-performing supply chain partner and despite intending to never work with that supplier again relented:

“… we sat down with them and said, look, if you want to get back with us, you’ve got to do this. They put that in place and I used them two years later. I was singing their praises, thought they were absolutely fantastic. …So it's about developing everybody as well” (r1)

In this particular case, the specialist's willingness to engage in supplier development carried an informal obligation for reciprocity, as the supplier has subsequently helped the specialist through times of need.

“And they got us out of sticky situations two or three times”. (r1)

CitationBurt (1992) claims benefits from network ties occur in three forms – access, timing, and referrals. Access and timing, in this case, enabled a rapid response – ‘the capacity to meet priorities and achieve goals in a timely manner in order to contain losses and avoid future disruption’ (CitationKendra & Wachtendorf, 2003).

Two forces counteract the potential for some contractors to not reciprocate or to behave opportunistically. First, is the risk of being removed from the framework. The second is peer pressure from other community members. Respondents identified specialist contractors who did not commit to the community element of the framework and took an ‘easy ride’ (r10). The 360° feedback sessions played an important role in identifying a perceived lack of commitment and acted as a means of applying peer pressure. Many respondents identified strongly with the CMF, a view expressed in drawing comparisons with other clubs where membership involves responsibilities as well as benefits. Identification may act as a resource influencing the anticipation of value to be achieved through exchange and combination and the motivation to do so (CitationNahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). CMF members have been able to anticipate adding value by engaging with each other for works outside the framework.

Collectively, we have highlighted how the three dimensions of social capital have influenced organisational behaviours within the CMF and how these have been exploited for organisational resilience in maintaining positive adjustment under challenging conditions (CitationWeick, 1993). The examples, drawn from the CMF above, indicate how structural, cognitive and relational dimensions have contributed to robustness, redundancy, rapidity and resourcefulness reflected in a significant improvement in community performance than previous arrangements.

7 Organisational resilience

To use an accounting term the CMF has enabled the accrual of social capital enabling the community to respond to difficulties in a creative way. As identified earlier, the absence of social capital at Mann Gulch was key to explaining why many died when they might have survived. Using the sources of resilience identified in CitationWeick's (1993) analysis the CMF's emphasis upon continuous improvement and effective communications, with the emergence of trust, facilitated creativity in responding to problems. This enabled the first of Weick's sources of resilience. Bricolage emerged through the combination of creativity with the willingness of members to share resources and expertise. These were facilitated by the structural arrangements of the CMF, reinforced by the shared cognitive processes and trust underpinning the relationships. Together these contributed to the robustness of the CMF.

Weick's notion of Virtual roles, a second source of resilience, began with the early involvement of specialists and supply chain partners in shaping the project from its inception. This created the potential for shared understanding of one another's roles resulting in the possibility of standing in for an absentee, whether they are physically or cognitively absent.

“You start thinking what he is thinking and the answers become self explanatory” (r16)

“… you’re sat in with 10 other people who you know really well. Especially now it's 7 years. Nine times out of ten there's not even an introduction because everyone knows each other and if there is, it's the odd person. And you get to know how people work and how they think”. (r10)

The ability to substitute for absent members or resources represents redundancy and resourcefulness dimensions along which resilience can be evaluated (CitationKendra & Wachtendorf, 2003).

The third source is what Weick described as Attitudes of Wisdom, ‘the capacity to question what is known, to appreciate the limits of knowledge, and to seek new information’. A good example of an attitude of wisdom lays in the members’ ability to challenge traditional forms of contracting and engage in a fundamentally different approach. From the conception of the CMF the membership's buy-in and participation in establishing community values have shaped new or different behaviours and relationships. That this builds over time was evident from the data with many members identifying how they had adapted to this new approach.

Finally, Weick's notion of respectful interaction implies trust, an element of relational social capital. Trust can be seen in the willingness to be vulnerable to another party – a belief in their reliability (CitationMishira, 1996). Respectful interaction is evident in the conduct and feel at ‘setting the scene’ meetings, project progress meetings, interim and final project performance reviews. This is not to suggest that these settings are cosy. To the contrary, some of the meetings attended at times became heated, but all the meetings attended resulted in agreement upon which contractors respected and were willing to act.

“There's mutual respect between the contractors… In this industry, if you’re not very good at your job, you tend to get found out… It makes the job easier if everybody gets on… You don’t want conflict. What the framework does is it gives you the opportunity to sit down and sort things out…” (r1)

This paper has sought to depict structural, cognitive and relational dimensions of social capital that contributed to greater resilience. We have also drawn upon our knowledge of resilience to highlight specific components of resilience, from positive adjustment to Weick's recommendations for building team resilience.

8 Discussion

This paper has described how a public–private partnership has achieved some degree of organisational resilience; with a demonstrable capacity to respond quickly and creatively to potential threats and to prevent them from escalating into crises. It has demonstrated how the combination of CitationNahapiet and Ghoshal's (1998) dimensions of social capital were employed within the CMF and achieved outcomes comparable to the aspirations identified in definitions of BCM.

Earlier we asked how might success in crisis management (in this case BCM) be recognised or evaluated. In the first part of this paper the growing influence of the audit was identified in general and with specific reference to BCM. The growing use of audits in the context of crisis management may be seen as a proxy measure of effectiveness given the relative rarity of crises, and/or an effort at quality assurance where a certificated process is assumed to reflect a real capability. The failures of public bodies in Gloucestershire highlighted the potential dangers of over confidence in ‘certified’ processes which may focus on only those elements readily assessed.

Conversely, although some key structures, cognitive processes and relationships have been explored, it is not clear that these could be measured easily without losing the essence of the community in relation to cognitive processes, norms and trust. It does not lend itself readily to the translation into a simple or codified recipe of structures, processes and tools, central to CitationComfort et al.’s (2010) notion of resilience. It would be difficult to audit the processes and informal/formal ties, operating norms and culture of the CMF. It is more time consuming to capture what is going on and to prepare the evidence required to demonstrate effectiveness than in a more static, certificated assessment with its emphasis upon documented processes and hard artifacts.

In this light, CitationPitt's (2008) recommendation that key civil emergency responders should comply with a standard equivalent to BS25999 may be interpreted as insufficient on its own. Compliance with the standard is a dubious proxy measure for crisis management (BCM) effectiveness. Such a recommendation fits however, with the need for a public inquiry to be seen to deal with many issues. CitationElliott and Smith (1993) recorded how CitationWheatley's (1972) investigation of stadium disasters arbitrarily incorporated preliminary technical research into its recommendations and guidance for practice, only to discover that they were flawed some years later. The inclusion of explicit knowledge or codified processes fits well implicit views of learning from crisis, which see learning as the translation of codified lessons into practice (CitationElliott, 2009).

The CMF suggests that learning ‘for’ and ‘from’ crisis might be better focused upon understanding both tacit and explicit knowledge and processes. Policy makers and practitioners might be better devoting greater attention to the tacit dimension of crisis management than prescribing limited fixes. As CitationParaskevas's (2006) case demonstrated, there is the danger that when crisis management becomes a drilled response, with an exclusive focus upon performance, the adaptation necessary to respond effectively to a crisis may fail.

Elements of social capital within the CMF permitted adaption to emerge within or alongside the performance system. Fundamental to this was the shift in the pattern of relationships prior to the CMF, from adversarial and contractual in nature, to a more collaborative approach. It was evident that the structures, emergent cognitive processes and relationships established created the conditions for organisational resilience. In particular, structural linkages of the CMF, with associated norms, provided a fertile context for bricoleurs to respond creatively. This was supported by a culture of respectful interaction, reinforced by the notion of equal voice and with contractors seen as specialists and subcontractors as partners. The early involvement of all community members in the project ensured a good level of understanding of the various roles required to achieve the Framework's objectives. This enabled, in a number of instances, one member to assume the role of another. This possibility of substitution would not have been available under the pre-framework arrangements.

The framework created a new structural form, and with it the possibility of a new way of working, one that emphasised the common good rather than individual benefit. This is not to say that it was always comfortable or that members never pursued selfish interests. What was evident from the data, however, was a commitment to the collective. This emerged, resulting in better project performance in terms of keeping to budget and achieving goals within deadlines.

9 Conclusion

This paper has argued that social capital, in the form of structural, relational and cognitive dimensions, may help establish the conditions for organisational resilience. The CMF case study illustrates how a public body chose new supplier arrangements to overcome previously poor performance, resulting in significant improvements, and the ability to deal with small and major potential interruptions. This capability, we argue, was made possible by the social capital accrued through the new partnership and was manifest in bricolage, attitudes of wisdom, respectful interaction and virtual roles. Alternatively, there is evidence of each of the four dimensions identified by CitationKendra and Wachtendorf (2003). The structures, relationships and cognitive processes made possible within the CMF were vital in creating the conditions for these to emerge. The case illustrates how a public body can play an important role in encouraging new forms of working and relationship management that may contribute to more resilient organisations.

The case of the CMF provides an example of success in terms of its ability to perform better than previous arrangements and in its ability to adapt and deal with interruptions effectively. As such it achieves the objectives of BCM. These contrast sharply with the experience of Gloucestershire County Council which failed, despite its awards for good practice, and suggest that caution should be taken in accepting the results of certification as definitive evidence of crisis management success. The hubris potentially associated with major awards and honours may be revealed as unwarranted pride after subsequent failure. Success may be better viewed as a deep seated capability, embedded within a community of organisations that is willing and enable to retain the necessary focus upon performance or exploitation alongside the ability to adapt or explore at times of potential crisis. Such capabilities are founded upon a combination of structures, processes and tools and how they are brought together. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

A key lesson for policy makers and practitioners is to consider alternative means of achieving the same end. There is a tendency for learning from crisis to focus upon preventing a repeat of past failures. Lessons identified may become enshrined in notions of best practice such formal standards or as in the case of Gloucestershire, the award of “Beacon Status”. It has been argued that a potential weakness of learning from experience is that it may not help prepare for unforeseen scenarios or similar ones which involve different personnel or technologies. Rather it may only prepare us to rerun what we have learned and to make sense of and enact practice in a similar scenario (CitationElliott & Macpherson, 2010). This echoes CitationPerrow's (1984) observation that accident investigations are often ‘left censored’ in that they examine only failures and not systems with the same characteristics that have not failed. To counter this threat policy makers and practitioners might benefit from reflection upon alternative means of achieving similar goals. As the case of the CMF illustrates, the objectives of BCM, in terms of anticipating threats, protecting value creating activities and building resilience were achieved by very different means than traditional business continuity planning.

References

- W.N. Adger . Social capital, collective action and adaptation to climate change. Economic Geography. 79 2003; 387–404.

- P.S. Adler , S. Kwon . Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review. 27 2002; 17–40.

- M. Ansell , R. Evans , M. Holmes , A. Price , C. Pasquire . An application of the construction management framework in highways major maintenance. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. 16(2): 2009; 162–174.

- A. Boin . Learning from crisis: NASA and the challenger disaster. A. Boin , A. McConnell , P. ’t Hart . Governing after crisis: The politics of investigation, accountability and learning. 2008; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge 232–254.

- A. Boin , P. ‘tHart , E. Stern , B. Sundelius . The politics of crisis management. 2005; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- L.M. Branscomb , E.O. Michel-Kerjan . Public–private collaboration on a national and international scale. P.E. Auerswald , L.M. Branscomb , T.M. La Porte , E.O. Michel-Kerjam . Seed of disaster: Root of response how private action can reduce public vulnerability. 2006; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

- BSi, 2006 BSi . Business continuity management – Part 1: Code of practice. 2006; London BSi British Standards.

- J. Buckland , M. Rahman . Community-based disaster management during the 1997 red river flood in Canada. Disasters. 23(2): 1999; 174–191.

- R.S. Burt . Structural holes: The social structure of competition. 1992; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA

- R.S. Burt . Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital. 2005; Oxford University Press: New York, NY

- J.C. Coleman . Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 94 1988; S95–S120.

- L.K. Comfort , A. Boin , C.C. Demchak . Designing resilience – Preparing for extreme events. 2010; University of Pittsburgh Press.

- J. Corbin , A. Strauss . Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology. 13(1): 1990; 3–21.

- M. de Bruijne , A. Boin , M. van Eeten . Resilience: Exploring the concept and its meanings. L.K. Comfort , A. Boin , C.C. Demchak . Designing resilience: Preparing for extreme events. 2010; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh

- L. Drennan , A. McConnell . Risk and crisis management in the public sector. 2007; Routledge: London

- M. Easterby-Smith , R. Thorpe , A. Lowe . Management research: An introduction. 1991; Sage: London

- J.L. Egan . Rethinking construction: The report of the construction task force to the Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott, on the scope for improving the quality and efficiency of UK construction. 1998; Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions: London

- D. Elliott . The failure of organisational learning from crisis – A matter of life and death?. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 17(3): 2009; 157–168.

- D. Elliott , N. Johnson . A study of resilience and business continuity practice. 2010; University of Liverpool: Liverpool

- D. Elliott , A. Macpherson . Policy and practice: Recursive learning from crisis. Groups and Organisation Management. 35(5): 2010; 572–605.

- D. Elliott , D. Smith . Learning from tragedy: Sports stadia disasters in the UK. Industrial and Environmental Crisis Quarterly. 7(3): 1993; 205–230.

- D. Elliott , E. Swartz , B. Herbane . Business continuity management: A crisis management approach. 2002; Routledge: London

- ESRC, 2007 ESRC. (2007). What is social Capital? Available from: http://www.esrcsocietytoday.ac.uk/ESRCInfoCentre/facts/index54.aspx?ComponentId=12726&SourcePageId=20615 Downloaded 01.03.08..

- Freeman et al., 2004 Freeman, S. F., Hirschhorn, L., & Maltz, M. (2004). Organisational resilience and moral purpose: Sandler O’Neill and partners in the aftermath of 9/11/01. Paper presented at the National Academy of Management meetings, New Orleans, LA..

- F. Fukuyama . Social capital. Civil Society and Development Third World Quarterly. 22 2001; 7–20.

- M. Gargiulo , M. Benassi . Trapped in your own net? Network cohesion, structural holes, and the adaptation of social capital. Organisation Science. 11(2): 2000; 183–196.

- R. Garnham . Scrutiny inquiry into the summer emergency 2007. 2007; Gloucestershire County Council Internal Report: Gloucester

- B. Glaser , A. Strauss . The discovery of grounded theory. 1967; Aldine: Chicago

- J.M. Kendra , T. Wachtendorf . Elements of resilience: After the world trade center disaster: Reconstructing New York City's Emergency Operations Center. Disasters. 27(1): 2003; 37–53.

- C.R. Leana , H.J. van Buren . Organisational social capital and employment practices. The Academy of Management Review. 24(3): 1999; 538–555.

- C.A. Lengnick-Hall , T.E. Beck . Adaptive fit versus robust transformation: How organisations respond to environmental change. Journal of Management. 31 2005; 738–757.

- J.G. March . Exploration and exploitation in organisational learning. Organisation Science. 2 1991; 71–87.

- A.D. Meyer . Adapting to environmental jolts. Administrative Science Quarterly. 27 1982; 515–537.

- D. Miller . The Icarus Paradox. 1990; Harper Business: New York

- A.K. Mishira . Organisational responses to crisis. The centrality of trust. R.M. Kramer , T.M. Tyler . Trust in organisations. 1996; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA 261–287.

- B. Murphy . Locating social capital in resilient community-level emergency management. Natural Hazards. 41 2007; 297–315.

- J. Nahapiet , S. Ghoshal . Social capital, intellectual capital, and organisational advantage. Academy Management Review. 23 1998; 242–266.

- T.D. O’Rourke . Critical infrastructure, interdependencies, and resilience. Bridge. 37(1): 2007; 22–30.

- A. Paraskevas . Crisis management or crisis response system? A complexity science approach to organisational crises. Management Decision. 44(7): 2006; 892–907.

- T.C. Pauchant , I. Mitroff . Crisis prone versus crisis avoiding organisations: Is your company's culture its own worst enemy in creating crisis?. Industrial Crisis Quarterly. 2 1988; 53–63.

- T.C. Pauchant , I. Mitroff . Transforming the crisis-prone organisation. Preventing individual organisational and environmental tragedies. 1992; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco

- C. Perrow . Normal accidents. 1984; Basic Books: New York

- M. Pitt . The Pitt review: Learning lessons from the 2007 floods. 2008; The Cabinet Office: London

- R. Putman . Making democracy work. 1993; Princeton University Press: Princeton

- D. Robb . Building resilient organisations. OD Practitioner. 32(3): 2000; 27–32.

- T. Schuller . Reflections on the use of social capital. Review of Social Economy. LXV(1): 2007; 11–28.

- P. Shrivastava . Bhopal. 1987; Cambridge, MA: Ballinger

- D. Smith . Crisis management – Practice in search of a paradigm. D. Smith , D. Elliott . Key readings in crisis management. 2006; Routledge: London

- D. Smith , D. Elliott . Exploring the barriers to learning from crisis. Management Learning. 38(5): 2007; 519–538.

- K.M. Sutcliffe , T. Vogus . Organising for resilience. K.S. Cameron , J.E. Dutton , R.E. Quinn . Positive organisational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline. 2003; Berrett-Koehler: San Francisco 94–110.

- L.M. Svedin . Organisational cooperation in crises. 2009; Farnham, Ashgate Publishing Co.

- B.A. Turner . The organisational and interorganisational development of disasters. Administrative Science Quarterly. 21 1976; 378–389.

- K.E. Weick . The collapse of sensemaking on organisations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly. 38 1993; 628–652.

- K.E. Weick , K.M. Sutcliffe , D. Obstfeld . Organising for high reliability. Research in Organisational Behaviour. 21 1999; 81–123.

- Wheatley, 1972 Wheatley (Lord) . Report of the inquiry into crowd safety at sports grounds. 1972; HMSO: London (Cmnd 4952).

- A. Wildavsky . Searching for safety. 1988; Transaction Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA