Abstract

In an interconnected world, higher education systems, the institutions that comprise them, educational policy makers, quality assurance agencies are all supposed to interact simultaneously in a global, national, and local, or glonacal, context. Like some other Asian nations, Taiwan has been developing its glonacal quality assurance framework. At the same time, it attempted to give more institutional autonomy to universities by awarding them a self-accreditation status. The main purpose of the paper is to examine transformation of QA systems in Taiwan's higher education under the glonacal context and to analyze the new development of self-accreditation.

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, all Asian nations have developed their own quality assurance system by setting up a national accreditor whose principal role is to accredit local tertiary education institutions and academic programs. Prior to the establishment of their current national accreditor, local accreditors had emerged in some Asian countries, such as the Japan University Accreditation Association, founded in 1947, the Shanghai Education Evaluation Institute in 1996, and the Institute of Engineering Education Taiwan in 2003.

In response to the growing globalization of higher education, some Asian nations started to welcome international accreditors, particularly U.S. accreditors, to provide cross-border quality assurance services for local institutions (CitationEwell, 2008; Hopper, 2007). This led to a demand by the government and higher education institutions for international accreditation to be integrated into the national quality assurance framework (CitationStella, 2010; Woodhouse, 2010). The emergence of three types of accreditors, at local, national and global levels, meant that a “glonacal” quality assurance system was implicitly formed in some countries, including China, Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia and Taiwan (see CitationJarvis, 2014a; Wang, 2014; Yat Wai Lo, 2014). Some Asian nations with developing higher education systems as well as a young quality assurance agency, such as in Cambodia and Vietnam, have remained in the “non-glonacal” framework of quality assurance.

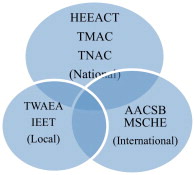

A decentralized system of quality assurance framework in Taiwanese higher education did not exist until a national accreditor, the Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT) was established in 2005 with funds from the government and 153 colleges and universities (CitationHEEACT, 2012). Prior to the establishment of HEEACT, several self-funded local accreditors had been founded, including Taiwan Assessment and Evaluation Association (TWAEA), Taiwan Medical Accreditation Council (TMAC), Taiwan Nursing Accreditation Council (TNAC), the Institute of Engineering Education Taiwan (IEET). In order to strengthen the international outlook and global competitiveness of Taiwan's colleges and universities, the MOE has internationalized Taiwan's higher education with several polices, including encouraging universities to seek international accreditation. Since then, Taiwan has been developing its glonacal quality assurance framework, like some Asian nations.

In 2013, the MOE launched a new policy of self-accreditation, which aimed at enhancing institutional autonomy as well as promoting an institution's internal quality mechanism. 34 recipients of Taiwan's Teaching and Research Excellent Programs have been invited to take part in the new initiative. Hence, the main purpose of the paper is to examine transformation of QA systems in Taiwan's higher education under the glonacal context and to analyze the new development of self-accreditation.

2 Asia glonacal QA systems and emergence of international accreditors

Throughout the centuries, “higher education has remained at the one and the same time, global, national and local. From its beginning, the university was always rooted in local settings, while at the same time it connected to a larger international field of knowledge” (CitationMarginson, Kaur, & Sawir, 2011, p. 5). At a time when the world is getting flatter, higher education systems, the institutions that comprise them, and educational policy makers, are all supposed to interact simultaneously in the global, national, and local contexts. Simon Marginson, a prominent Australian scholar, called this higher education phenomenon in the 21st century the “Glonacal” era (CitationMarginson, 2011). According to CitationMarginson (2011), the institution itself as a local organization, needs to respond to national policies in culture, politics and economics. With governmental support, local institutions will be able to develop their competitiveness successfully at the global context. Institutions are learning to integrate and balance the needs of varying stakeholders, including local students, national governments, and the global market, into the three dimensions of a “glonacal” area of higher education, in which “activity in each one of the global, national, and local dimension can affect activities in the others” (p. 14).

Asian higher education systems responded in various ways to glonacal trends including: growing social demand, privatization, accountability, marketization and economic growth. This response included the development of external quality assurance systems at the national level (CitationMatrin & Stella, 2007). As higher education institutions in Asia are going from local to global, they expect to be assessed beyond their national authority for graduate mobility and degree recognition. Within the global context, quality assurance services in Asia started to develop internationally in response to this pressure, leading to the emergence of international accreditors, particularly professional accreditors (CitationEwell, 2008; Hou et al., 2013). The number of professional accreditors, in fields such as business, engineering, medicine, nursing, architecture, and education, has increased rapidly due to the international mobility of graduates (CitationWoodhouse, 2010). Recently, these professional accreditors, especially U.S. business and engineering program accreditors, have begun to accredit academic programs not only in the United States but also abroad. For the purposes of increasing reputation and safeguarding enrollment, Asian institutions prefer to get international recognition rather than national and local accreditations. At the same time, some Asian countries, such as Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, continue to encourage local institutions to seek international accreditation in order to enhance academic competitiveness globally. CitationHayward (2001) pointed out the popularity of American accreditors: “Some foreign colleges and universities want U.S. accreditation because it is, at least at the moment, ‘the gold standard’ in many areas of higher education” (p. 6). CitationEwell (2008) responded that “U.S. accreditation may provide an additional cachet in a competitive local market especially for private institutions” (p. 153). Obviously, international accreditation is being sought by more and more institutions abroad as higher education globalizes in a very competitive manner (CitationHou, 2011; Morse, 2008). Therefore, no matter whether international accreditation is pursued by institutions voluntarily or under pressure from governments, it is likely to introduce “a commercial dimension to accreditation practices and the desire for institutions or providers to have as many accreditation labels or stars as possible” (CitationKnight, 2005, p. 2).

3 Three QA challenges in Asia: internationalization, autonomy, and accountability

In the glonacal quality assurance system the issues of “autonomy,” “internationalization,” and “accountability” have been the most crucial concerns for quality assurance agencies in Asia. First, due to the fact that Asian quality assurance agencies are either governmental institutions or are affiliated with a government, it has introduced the concern for the level of autonomy that impacts national and local quality assurance agencies in Asia. Although most QA agencies including those established and funded by their governments have claimed that they have autonomy over review procedures and decisions, several scholars have expressed their concerns over the issue. CitationBrown (2013) stated clearly that when the government develops QA initiatives as a part of higher education reform strategies, its intervention into quality assurance design becomes inevitable. CitationMatrin and Stella (2007) pointed out that “Getting the government to support the quality assurance process without losing any of the agency's autonomy or affecting its functioning is certainly an option to be considered” (p. 80). CitationDill (2011) also raises questions about how truly “independent, transparent, and robust” that the Asian quality assurance process actually is.

According to Asia Pacific Quality Network (APQN), Southeast Asian national QA agencies are established as governmental agencies. In contrast, Eastern Asian agencies tend to be a buffer body where the government likely plays a major role in the agency. However, both types of the agencies are expected to serve government functions, particularly the use of accreditation outcomes in educational policy making and funding allocation. Therefore, a study by CitationHou et al. (2013) showed that Asian QA agencies admitted that it was not easy to maintain their level of “autonomy” because of their close affiliations with their national government.

The second challenge is international capacity building of national accreditation. The internationalization of higher education often implies the pursuit of an international image of quality and prestige in order to make the selected top institutions more globally competitive (CitationDeem, Mok, & Lucas, 2008; see also CitationJarvis, 2014b). This rationalizes the emergence of internationalization of quality assurance in Asia, which, taken as a symbolic and powerful indicator, is used to prove the quality standards of local institutions in a globally competitive education market (CitationEwell, 2008). The fact that institutions in Asia are encouraged by governments to seek international accreditation, particularly from the U.S., has contributed to a new concern of national accreditors over internationalization in Asia. In response to global trends and local demand, national accreditors are expected to be the quality gatekeepers of cross-border education. However, it can be found that most quality assurance agencies in Asian countries are still confined to national contexts, and have no capacity to evaluate cross-border academic programs at home or abroad. Currently, Asian quality assurance agencies have attempted to strengthen their international capacity in terms of networking and exchanges with other agencies via Asian Pacific Quality Network (APQN) and The International Network of Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE) (CitationAPQN, 2012).

Finally, to credibly demonstrate accountability of the quality assurance procedures is the third challenge faced by Asian quality assurance agencies. Since quality assurance became recognized as a profession in recent years, quality assurance agencies are supposed to be “under review and development to ensure that they remain current and relevant” on the basis of a systematic scheme of quality (CitationWoodhouse, 2010, p. 79). This is referred to as “accountability of accreditation” (CitationEaton, 2011). A 2011 survey targeting on seven Latin American countries by the International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE) showed that quality assurance has both positive and negative impacts on higher education, including its influence on policy decision and processes, increase value placed on teaching as a core function of universities, leading to an increased bureaucratization and heavy administrative workload. The survey also found that most positive consequences were occurring at the program level (CitationLemaitre, Torre, Zapata, & Zentrno, 2011). Nevertheless, there is still little evidence about the actual impact of quality assurance on universities and colleges in Asia nations although they have set up a national quality assurance system and higher education institutions have gone through the accreditation processes, including preparing self-study reports, experience of on-site visits, etc.

4 Taiwan quality assurance system from centralized to decentralized in a glonacal context

4.1 Development of Taiwan quality assurance system

Because the number of Taiwan's higher education institutions increased dramatically since the 1980s, the public's desire to maintain and increase both “quantity” and “quality” has placed tremendous pressure on Taiwan's government. Apart from encouraging institutions to conduct assessments on their own, a few professional associations such as the Chinese Management Association, the Chemical Society and the Physical Association of the Republic of China were chartered by the Ministry of Education to exercise program-based academic assessments beginning in the 1980s. In the 1990s, the government, having been continuously pressured by the public, began implementing a wide range of comprehensive institutional evaluations with the goal of establishing a non-governmental professional evaluation agency whose purpose was to conduct evaluations of higher education institutions (CitationHou, 2011).

In 1994, Taiwan's Congress, Legislative Yuan passed the “University Law” which stated clearly that the national government is entitled to university evaluation in order to assure higher education quality. In 2005, the Ministry of Education revised the “University Law”, stipulating that “universities should periodically undergo self-evaluation on teaching, research, service, counseling, administration, and student engagement; evaluation guidelines should be set forth by each university” (CitationHou, 2011; MOE, 2005). Under the law, the Ministry of Education was obliged to “set up evaluation committees or support professional accrediting agencies to periodically conduct university evaluations and publish their results as reference for the government to allocate subsidy and the institutions to adjust their future development plans” (CitationHou, 2011; MOE, 2005).

According to the law, the Ministry of Education funded the establishment of Higher Education Evaluation & Accreditation Council (HEEACT) in 2005. In fact, several local accreditors had already begun providing quality assurance services to Taiwan's institutions prior to HEEACT, such as the Taiwan Assessment and Evaluation Association (TWAEA), which mainly undertook institutional assessment of Taiwan's technology universities. There are three other Taiwan professional accreditors in medicine, nursing and engineering. As the oldest professional accreditor, Taiwan Medical Accreditation Council (TMAC) established by the National Health Research Institute in 1999, aims to assess all medical schools. The other professional accreditor, Taiwan Nursing Accreditation Council (TNAC) was set up by the Ministry of Education in May 2006 to conduct nursing program evaluations. After the establishment of HEEACT in 2005, TMAC and TNAC were officially moved into the HEEACT office. Due to the unique features of medical and nursing education, they have remained as independent accrediting agencies (CitationHEEACT, 2010). Founded in 2003, the Institute of Engineering Education Taiwan (IEET) is an independent, non-governmental and not for profit organization committed to accreditation of engineering and technology education programs in Taiwan. The difference between local accreditors and HEEACT is that these accreditors are self-funded institutions offering services on a voluntary basis. Those who voluntarily apply for accreditation by the local accreditor have to pay the fees by themselves.

Prior to the establishment of Taiwan's current quality assurance framework, Taiwan's universities had started to seek international quality recognition to sharpen their global competitive edge, particularly from AACSB International in the U.S. (CitationHou, 2011). Some of Taiwan's universities have also started to pursue U.S. institutional accreditation. The Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE), an American institutional level “regional” accreditor, which began a pilot project accrediting non-U.S. institutions in 2002, accredited Ming Chuan University in 2010.

In order to eliminate the duplication among various accrediting agencies and to lessen the institutional burden, in 2009, Taiwan's Ministry of Education announced “exemption policy”. If a program or an institution is accredited by international accreditors recognized by the MOE's task force of “Local and International Accreditors’ Recognition”, it will not need to be assessed or re-assessed by HEEACT. Up to mid-2014, the task force had recognized three local accreditors, and two U.S. accreditors, including TWAEA, IEET, Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (ACCSB), AACSB, and Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE).

As a result of these developments, a working outline of the “glonacal” quality assurance system in Taiwan higher education has been formed (Fig. 1 ). HEEACT, AACSB and IEET are the representatives in each type.

4.2 Analysis of three types of accreditations

4.2.1 HEEACT (National)

As a national accreditor, HEEACT operates both institutional and program based accreditation. The external review costs are completely covered by the MOE. The detailed final reports are published on HEEACT's official website. In 2006, HEEACT began a 5-year, program-based, and nation-wide accreditation. The standards developed in the first cycle of program accreditation are as follows: (1) goals, features, and self-enhancement mechanisms; (2) curriculum design and teaching; (3) learning and student affairs; (4) research and professional performance; (5) performance of graduates. There are three types of accreditation outcomes, including “Accredited,” “Accredited Conditionally,” and “Denial” (CitationHEEACT, 2012). According to HEEACT, the average rate in the first cycle for accredited status among a total of 1870 programs is 86.11%, for conditionally accredited 11.84%, and for denied 1.97% (CitationHEEACT, 2012).

Starting in 2011, HEEACT conducted a new comprehensive assessment over 81 4-year national and private universities and also continued the second cycle program accreditation. Following the global trend of quality assurance, both institutional and programmatic accreditation focused on the assessment of student learning outcomes. In HEEACT's handbook of the 2011 institutional accreditation, it emphasized that an institution will be evaluated and examined according to PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) model and the based evidence: first it should have a clear mission to state its institutional identity; second, it should have favorable governance to integrate and allocate resources; third, it should have set up a mechanism to assess student learning outcomes (CitationHEEACT, 2011).

The second cycle of program accreditation stressed the aim of realizing the development and operation of student learning outcomes evaluation mechanisms within programs and disciplines. The new accreditation model has been adopted to assist universities in analyzing their strengths and weaknesses to facilitate successful student learning. The new standards for the second cycle of program accreditation were as follows: (1) educational goals, features and curriculum design; (2) teaching quality and learning assessment; (3) student guidance and learning resources; (4) academic and professional performance; (5) alumni performance and self-improvement mechanism (CitationHEEACT, 2012). Generally speaking, universities and programs were encouraged to develop measurable learning outcomes, to develop a variety of assessment tools at the course, program and institutional level, and to establish whether the learning outcomes are met. According to HEEACT, the pass rate of the second cycle program accreditation was up to 98.3% in the academic year of 2013 (CitationHEEACT, 2014).

4.2.2 IEET (Local)

As a professional accreditor, IEET implemented accreditation in the fields of Engineering (EAC), Computing (CAC), Technology (TAC), and Architecture (AAC). IEET adopted outcome based criteria to ensure the desired graduate achievements or learning outcomes and made a continuous self-enhancement of overall quality. IEET stated clearly that accredited programs will be able to improve teaching quality according to a variety of assessment outcomes. There are nine criteria over accreditation, including educational objectives, quality and capabilities of the students and graduates, program outcomes and assessment, curriculum, faculty qualification, space and facilities, institutional support and financial resources, discipline-based criteria, and minimum requirements of accreditation for the Master's degree education (CitationIEET, 2014). IEET only publishes the list of the programs accredited.

To assist graduates in accredited programs for entry to the practice of engineering, IEET applied and was admitted to the Washington Accord as a Full Signatory in 2007. In 2009, IEET was accepted by the Seoul Accord on accreditation of Computing and IT–related programs as a full member. The Washington Accord and Seoul Accord are international agreements among bodies responsible for accrediting engineering degree programs. They “recognize the substantial equivalency of programs accredited by those bodies and recommend that graduates of programs accredited by any of the signatory bodies as having met the academic requirement” for entry to the professional practice (CitationInternational Engineering Alliance, 2011a, 2011b). Currently, IEET's accredited programs are recognized by the governments of signatories, including Singapore, Malaysia, U.S., Canada, and Hong Kong. In 2004, only 12 Taiwan's engineering program applied for IEET accreditation, but in 2007, there have been 137 programs accredited, a 10-time increase. After the MOE's exemption policy was announced, there were more than 450 programs in 74 institutions accredited by IEET in 2011.

4.2.3 AACSB (International)

Established in 1916, AACSB International has aimed to provide “its members with a variety of products and services to assist them with the continuous improvement of their business programs and schools” through a set of standards on school's missions, governance, faculty qualifications and student learning (CitationAACSB International, 2014). AACSB accreditation emphasizes that various stakeholders, including students, parents, and employers, should be provided with top-quality business education. In 1991, AACSB began its international accreditation activities, expecting that the accredited institutions would be given many benefits by attracting higher quality students, providing greater research opportunities, and allowing for global recognition (CitationAACSB International, 2011). Up to 2014, there were 1350 AACSB members, including 694 accredited institutions. 74 of the total number of AACSB accredited institutions are from Asian countries, 10.6% of the total (CitationAACSB International, 2014) (see ).

Table 1 Number of AACSB accredited institutions from Asian countries.

Source: CitationAACSB International (2014).

Schools Accredited in Business https://www.aacsb.net/eweb/DynamicPage.aspx?Site=AACSB&WebCode=AccredSchlCountry.

To become AACSB-accredited in business and/or accounting, an institution must satisfy the eligibility requirements and the 21 accreditation standards in three sections, including strategic management, student and faculty, and assurance of learning. AACSB's international accreditation has a great impact on accredited institutions in many ways, especially on internationalization, governance, and assurance of learning. According to a 2009–10 Collaborations Survey data by AACSB, there were 3950 unique collaborations between AACSB member institutions. The survey showed that 83% of respondents agreed that AACSB Accreditation assisted them to “collaborate and partner with other high-quality business programs/schools in their country or region” (CitationAACSB International, 2011).

In addition, some studies discovered that AACSB accreditation assisted local deans of business schools to have better opportunities to manage the institutions as well as to consolidate their institutional positions within the universities (CitationCret, 2011). Developing an Assurance of Learning (AoL) system is one of the major components for AACSB accredited programs whose “learning goals should align with a school's mission, and outline the knowledge, skills, and capabilities a graduate should possess when leaving the school” (CitationAACSB International, 2014). Hence, faculty members are supposed to be involved to a far greater extent than they were before, particularly in developing learning goals, objectives, measurable outcomes, and assessment tools, etc. (CitationHazeldine & Munilla, 2004; Matrell & Calderon, 2005). However, other studies also show that how to measure what student learned is still a big challenge for most institutions (CitationPringle & Michel, 2007). In mid-2014, 10 business schools in Taiwan have gained AACSB International Accreditation up to present. Fu Jen Catholic University and National Sun Yat Shen University have been re-accredited in 2010. Thirty-one public and private Taiwan institutions have become members of AACSB International and are committed to the accreditation process (CitationAACSB International, 2014).

Their focus on learning outcomes and assessments have caused a significant impact on Taiwan higher education institutions and programs, particularly in integrating students’ basic literacy and core competencies which they should possess into curriculum (CitationMOE, 2012) ( ). Yet, compared to IEET and AACSB, HEEACT's accreditation was under severe criticism by some Taiwan scholars who claimed that its accreditation violated institutional autonomy and increased administrative work for faculty and staff (CitationHou, 2014; Tai, 2012). In addition, Taiwan university administrators’ attitude toward the AACSB and IEET accreditations tended to be very positive (CitationChan & Yang, 2009). It was also found that the institutions applying for international or local accreditation admitted that they did not want to be assessed by HEEACT due to the MOE's penalty's policy and its transparency (CitationChan & Yang, 2011; Hou, 2014).

Table 2 Comparison among three accreditations.

Source: By author.

To sum up, HEEACT has been regarded as a leading national accreditor due to its compulsory approach imposed by the national authority. AACSB, identifying itself as an international QA agency instead of being an American accreditor only, has been operating its accreditation globally for more than 20 years. AACSB is very popular in Taiwan because it is believed that the global competitiveness of an institution will be greatly enhanced through AACSB accreditation. Recognized officially by the MOE and Washington Accord signatories, IEET plays the local and global roles of connecting Taiwan's institutions to a “glonacal” context.

4.3 Three major concerns toward QA regulation

MOE's exemption policy and the proliferation of international accreditation in Asia have resulted in a “glonacal” quality assurance framework of higher education in Taiwan. The MOE exemption policy also addresses some critical issues in the national and international levels regarding QA regulation. First, Taiwan's government retains an indirect role of great influence on all these institutions by its policies of funding allocation and total enrollment control based on the review outcomes by Taiwan's national accreditors. Administrators at Taiwan's higher education institutions realize that a pass in the evaluation exercise is vital for the survival of an institution, due to the outcomes’ transparency. Those who failed to pass the national accreditations are required to make improvements according to the comments in the final report and will be under another review a year later. The failed programs will be eventually penalized by the MOE to cut down 50%–70% of their enrolment (CitationMOE, 2005). Although the MOE claimed that it would not force universities to close the unaccredited programs, most institutions wisely chose to close or merge them in order to avoid hurting a university's reputation. Thus, this has led to an ongoing dilemma called “the principal agent problem”, which means that the responsibility of the national agency is to ensure that government's wishes are in fact carried out although each may have its own agenda and mission (CitationEwell, 2008; Hawkins, 2006; Hou, 2011).

In the decentralized system, the institutions are given autonomy to the selection of the accreditors recognized by the MOE. The local and international accreditors are eager to provide their services to them, vice versa. Due to the fact that local and international accreditors are self-funded organizations and charge the applicants a certain amount of fees for review processes and other relevant activities, CitationKnight (2005) warned that “the need and desire for accreditation status is bringing about commercialization of quality assurance and accreditation” (p. 2).

Unlike other national and local accreditors, a light-touch approach was adopted by MOE's Task Force for recognition of international accreditors. It means that the government did not have to undertake a substantial review process and procedures over international accreditors if they are recognized by their home recognition bodies or as full members of INQAAHE and APQN (CitationMOE, 2009). The light-touch approach is interpreted as encouraging local institutions to seek international accreditation, which will conflict state control. In response to these dilemmas above, governments began implementing the new policy of self-accreditation for the selective universities in 2013.

5 New trends: self-accreditation and internationalization

5.1 Self-accreditation policy encouraging institutional autonomy

According to INQAAHE, self-accreditation is, “a process or status that implies a degree of autonomy, on the part of an institution or individual, to make decisions about academic offerings or learning” (CitationINQAAHE, 2013). In other words, self-accrediting universities are given autonomy to either award degrees in their own name or accredit their own programs without going through an external party. The purpose of self-accreditation is to develop quality culture on campuses throughout a rigorous internal quality review process by universities. Currently, Hong Kong, Australia, and Malaysia adopted the policy in Asia (CitationMQA, 2012; TEQSA, 2013; Wong, 2013)

Under the “glonacal QA framework”, the MOE determined to launch “self-accreditation” policy in 2012 in order to respond to the requests for university autonomy and to strengthen internal quality assurance (CitationMOE, 2013). Self-accrediting universities are expected to realize their strengths and weaknesses as well as to develop their own review standards. At the same time, they will be given authority to conduct an external evaluation over their programs without being reviewed by HEEACT. The new policy represented that a binary quality assurance system in Taiwan higher education dividing institutions into “self-accrediting” and “non-self-accrediting” types was formed.

According to the MOE, universities can apply for self-accreditation status, if they meet one of the following requirements: the recipients of the MOE grants of the Development Plan for World Class Universities and Research Centers of Excellence; (2) the recipients of the MOE grants of the Top University Project; (3) the recipients of the MOE grants of the Teaching Excellence Project with more than 6.7 million in USD in the consecutive 4 years. Currently, there are 34 Taiwan institutions that are eligible to apply for self-accreditation status.

There are two stages for applicants to be granted a self-accrediting status. In the first stage, the applicant is required to submit the documents and evidence demonstrate their capacity to conduct an internal review process. All documents will be reviewed by a recognition committee organized by the MOE. The review standards, including eight aspects (CitationMOE, 2013):

| 1. | University has set up its own self-accreditation regulations based on the consensus of the whole university. | ||||

| 2. | The self-accreditation standards developed by the university are properly integrated with its educational goals and uniqueness. | ||||

| 3. | A steering committee of self-accreditation is organized by the university and its responsibility is properly defined in the regulations. The committee consists of 3/5 outside-university experts. | ||||

| 4. | The whole review process of the self-accreditation is properly designed with multiple data resources and self-improvement function. | ||||

| 5. | The peer reviewers should be comprised of experienced experts, academic scholars, and industrious representatives. | ||||

| 6. | The self-accreditation system is fully supported by the university itself with enough financial support and human resources. | ||||

| 7. | A feedback system set up by the university continuously makes self-improvements according to the accreditation results and the review comments. | ||||

| 8. | The self-accreditation results are transparent and will be announced to the public. | ||||

The second stage focuses on the actual review process and procedures conducted by self-accrediting institutions and recognizing review outcomes by the institutions. The audit will be carried out by HEEACT through documents checks. After going through the HEEACT's audit, the MOE will approve self-accrediting institutions to publish their review outcomes.

Given the fact that universities are given autonomy to develop their features through self-accreditation process and procedures, they will be able to determine if they would like to go either international or remain local. The MOE does not set up specific regulations for either review criteria or composition of a review panel, but many applicants tend to strengthen “internationalization” in the review procedures. One third of the applicants incorporated “internationalization” aspect into one of the review items, such as enhancing students’ foreign language proficiency, deepening campus internationalization, developing faculty international capacities, etc. Moreover, several research-oriented universities decided to invite international reviewers to join on-site visit. Take Taiwan National University for example, it stipulated that all program reviews should include at least one international reviewer in the review panel.

5.2 National and local accrediting bodies toward internationalization

In addition to being challenged by international accreditors undertaking programmatic or institutional accreditations and by the government's exemption and self-accreditation policy, Taiwan's national and local agencies are also attempting to build their capacity and promote an international outlook through internal and external approaches. To help with their internal self-improvement, some of them have started to do self-evaluations, conduct meta-evaluation research projects to realize their own strengths and weaknesses, modify standards of accreditation into outcomes-based standards to meet the global trend, and promote mutual recognition of review decisions to enhance student mobility. In order to internationalize quality assurance standards, procedure and staff quality, Taiwan's agencies have established partnerships with foreign accrediting organizations and have participated in an international network of quality assurance in higher education to gain domestic and international recognition.

In the process of internationalization, Taiwan's accrediting agencies are facing big challenges. When they integrate Western standards, particularly U.S. ones, into the local context, they risk being criticized for assisting “cultural imperialism,” which raises the serious issue of national interest over higher education, particularly in institutional accreditation. This growing concern is especially ironic, considering the fact that local universities and accrediting organizations are applying international standards of accreditation and recognition in the national context (CitationEwell, 2008; Hou, 2011; Morse, 2008). Quality control in Taiwan with regard to higher education, it can easily be argued, is seemingly threatened by Anglo-Saxon standards and practices, and some might even say there is a risk of these becoming dominant.

Furthermore, top universities request national accrediting agencies to include international reviewers to serve on-site visits or Accreditation Committees, like some self-accrediting institutions are planning to do. This means further problems with respect to the international reviewer's training and recruitment policy. Communication in fluent English with a visiting international reviewer is challenging for most staff of Taiwan's agencies. The translation of materials or documents into English on websites is another big issue in the process of developing an international outlook and interactions with the international and regional quality assurance community. With insufficient human resources, all accreditors have to rely on few staff in an international exchange office to communicate with international reviewers. It is apparent that they are not ready yet for training of international reviewers and agency's staff. In addition, the high costs of international reviewers also constitute another concern for internationalization of Taiwan's quality assurance agencies (CitationHou, 2014).

6 Conclusion

A diversified system of quality assurance framework in Taiwanese higher education has been established in the “glonacal” context. Taiwan's “glonacal” quality assurance system not only assists the universities to set up a self-enhancement quality mechanism but also gives them more autonomy to develop their own features by choosing a suitable accreditation activity. But despite these positive effects, some issues concerning accreditation are still challenging Taiwanese society. These key questions include: whether the exemption policy violates national sovereignty over higher education; whether self accrediting institutions will be able to remain committed to quality improvement and enhancement; if national and local accreditors are unable to cater to local institutions’ need, then will those universities pursue international rather than local accreditation; whether international accreditors could actually enhance internationalization of accredited program as they claim, which would strengthen graduates’ employability in the global market; or whether local and international accreditation were too market-driven, which might distort university missions (CitationHou, 2014; Knight, 2005).

In fact, these challenges are a part of the impact that globalization is having on Taiwanese higher education. But the Taiwanese government believes that the preeminence of higher education increases both national economic strengths and international influence. Undoubtedly, the more that Taiwan's government concerns itself with maintaining the country's competitive edge in regional and global markets by open rules governing the quality of international accreditors and launching the self-accreditation policy, the more challenges national and local accreditors will face. Thus, these accreditation problems which include the international reputation of national and local accrediting agencies, the competition from foreign accrediting agencies, the integration of international into national standards of accreditation, the selection and training of international reviewers and staff, and the use of English, and the quality of national accreditors, self-accrediting institutions’ commitment to quality improvement will continue to challenge Taiwan quality assurance system into the foreseeable future.

References

- AACSB International . 2009–10 Collaborations survey. DataDirect. 2011 http://www.aacsb.edu/

- AACSB International . Website. 2014. Available from: http://www.aacsb.edu/ (accessed 02.02.10).

- Asia-Pacific Quality Network (APQN) . 2011 Annual report. 2012; APQN: Shanghai

- R. Brown . Mutuality meets the market: Analysing changes in the control of quality assurance in United Kingdom higher education 1992–2012. Higher Education Quarterly. 67(4): 2013; 420–437.

- Y. Chan , G.S. Yang . Meta evaluation on 2007–2008 program accreditation. 2009; Higher Education Evaluation & Accreditation Council of Taiwan: Taipei

- Y. Chan , G.S. Yang . Meta evaluation on 2010–2011 program accreditation. 2011; Higher Education Evaluation & Accreditation Council of Taiwan: Taipei

- B. Cret . Accreditation as local management tools. Higher Education. 61(4): 2011; 431–444.

- R. Deem , K.H. Mok , L. Lucas . Transforming higher education in whose image? Exploring the concept of the ‘world-class’ university in Europe and Asia. Higher Education Policy. 21(3): 2008; 83–97.

- D.D. Dill . Governing quality. R. King , S. Marginson , R. Naidoo . Handbook on globalization and higher education. 2011; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK

- J. Eaton . U.S. accreditation: Meeting the challenges of accountability and student achievement. Evaluation in Higher Education. 5(1): 2011; 1–20.

- P. Ewell . U.S. accreditation and the future of quality assurance. 2008; CHEA: Washington, D.C.

- D. Hawkins . Delegation and agency in international organization. 2006; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, U.K.

- F.M. Hayward . Finding a common voice for accreditation internationally. 2001. Available from: http://www.chea.org/international/common-voice.html .

- M.F. Hazeldine , L.S. Munilla . The 2003 AACSB accreditation standards and implications for business faculty: A short note. Journal of Education for Business. 80 2004; 29–35.

- Higher Education Evaluation & Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT) . 2009 Annual report. 2010; HEEACT: Taipei

- Higher Education Evaluation & Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT) . Handbook of institutional accreditation. 2011; HEEACT: Taipei

- Higher Education Evaluation & Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT) . 2011 Annual report. 2012; HEEACT: Taipei

- Higher Education Evaluation & Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT) . 2013 Annual report. 2014; HEEACT: Taipei

- R.R. Hopper . Building capacity in quality assurance the challenge of context. Cross-border tertiary education. 2007; OECD/The World Bank: Paris 109–157.

- A.Y.C. Hou . Quality assurance at a distance: International accreditation in Taiwan Higher Education. Higher Education. 61(2): 2011; 179–191.

- A.Y.C. Hou . Quality in cross-border higher education and challenges for the internationalization of national quality assurance agencies in the Asia-Pacific Region — Taiwan experience. Studies in Higher Education. 39(6): 2014. 163-152.

- A.Y.C. Hou , R. Morse , M. Ince , H.J. Chen , C.L. Chiang , Y. Chan . Is the Asian quality assurance system for higher education going glonacal?: Assessing the impact of three types of program accreditation on Taiwanese universities. Studies in Higher Education. 2013; 1–23. (online).

- Institute of Engineering Education Institute (IEET) . Official website. 2014. Available from: http://www.ieet.org.tw/InfoE.aspx?n=historyE (accessed 03.01.13).

- International Engineering Alliance . Washington accord. 2011. Available from: http://www.washingtonaccord.org/washington-accord/ (accessed 03.01.11).

- International Engineering Alliance . Seoul accord. 2011. Available from: http://www.washingtonaccord.org/Seoul-accord/ (accessed 03.01.11).

- International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE) . Analytic quality glossary. 2013. Available from: http://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/glossary/selfaccreditation.htm (accessed 01.12.13).

- D.S.L. Jarvis . Policy diffusion, neo-liberalism or coercive institutional isomorphism? Explaining the emergence of a regulatory regime for quality assurance in the Hong Kong higher education sector. Policy and Society. 33(3): 2014; 237–252.

- D.S.L. Jarvis . Regulating higher education: Quality assurance and neo-liberal managerailism in higher education — A critical introduction. Policy and Society. 33(3): 2014; 155–166.

- J. Knight . The international race for accreditation. International Higher Education. 2005; 40. Available from: http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/soe/cihe/newsletter/Number40/p2_Knight.htm .

- M.J. Lemaitre , D. Torre , G. Zapata , E. Zentrno . Impact of quality assurance on university work: an overview in seven Iberoamerican countries. 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2012 http://www.copaes.org.mx/home/docs/docs_Proyecto_ALFA_CINDA/Impact%20of%20QA%20processes%20in%20LA%20-%20Lemaitre%20et%20al.pdf .

- Malaysia Qualifications Agency (MQA) . 2011 Annual report. 2012. Available from: http://www.mqa.gov.my/portal2012/publications/reports/annual/Laporan%20Tahunan%202011.pdf (accessed 22.12.13).

- S. Marginson . Imagining the global. R. King , S. Marginson , R. Naidoo . Handbook on globalization and higher education. 2011; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham 10–39.

- S. Marginson , S. Kaur , E. Sawir . Global, local, national in the Asia-Pacific. S. Marginson , E. Kaur , Sawir . Higher education in the Asia-Pacific. 2011; Springer: Dordrecht 3–34.

- K. Matrell , Y. Calderon . Assessment in business schools: What it is, where we are, and where we need to go now. K. Martell , T. Calderon . Assessment in business schools: Best practices each step of the way. Vol. 1 2005; Association for Institutional Research: Tallahassee, FL 1–26.

- M. Matrin , A. Stella . External quality assurance in higher education: Making choices. 2007; UNESCO: Paris

- Ministry of Education . Revised University Law. 2005

- Ministry of Education . Provisions of local and international accreditors’ recognitions. 2009

- Ministry of Education . Higher education in Taiwan 2012-201. 2012; Ministry of Education: Taipei

- Ministry of Education . Provisions of self-accrediting institutions’ status recognitions and review outcomes’ approval. 2013; Ministry of Education: Taipei

- J.A. Morse . US regional accreditation abroad: Lessons learned. International higher education. 2008. Available from: http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/soe/cihe/newsletter/Number53/p21_Morse.htm (accessed 27.02.09).

- C. Pringle , M. Michel . Assessment practices in AACSB-accredited business schools. Journal of Education of Business. 82 2007; 202–211.

- A. Stella . The Chiba principles: A survey analysis on the developments in the APQN membership. 2010; Asia-Pacific Quality Network: Shanghai

- P.F. Tai . Absurd higher education evaluation. 2012. Available from: http://2012theunion.blogspot.tw/2012/10/blog-post_1.html (accessed 01.10.12).

- Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) . Self-accrediting authority. 2013. Available from http://www.teqsa.gov.au/for-providers (accessed 22.12.13).

- Li Wang . Quality assurance in higher education in China: Control, Accountability and Freedom. Policy and Society. 33(3): 2014; 253–262.

- M.S. Wong . External quality assurance under a self accreditation system: Promoting and assessing internal quality assurance. Paper presented in the 2013 Annual Conference of International Network for Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE). April 8–11, Taipei, Taiwan 2013

- D. Woodhouse . Internationalization of quality assurance: The role played by the networks. 2010. Available from: http://www.auqa.edu.au/files/presentations/internationalisation_of_qa___the_role_p layed_by_the_networks.pdf (accessed 15.02.11).

- W. Yat Wai Lo . Think global, think local: The changing landscape of higher education and the role of quality assurance in Singapore. Policy and Society. 33(3): 2014; 263–273.