Abstract

The complex and globalized nature of many industries has led to a global governance deficit that has resulted in the rise of self-regulation by private firms. Despite well-developed body of literature, we know little about the interaction of private regulation and public governance. The questions this paper addresses are: How do private self-regulatory programs either fill a vacuum of regulation or complement existing regulatory structures, and how do these programs support or crowd out the development of government regulatory programs? This paper addresses these questions by developing case studies of internal audit, voluntary reporting, and data analysis programs operated by the International Air Transport Association (IATA). The results suggest that when there is a congruence of goals between industry and government, private regulatory programs can complement or even replace existing public sector regulatory regimes. Additionally, the results suggest that successful private self-regulatory programs can often be threatened by competing public programs.

1 Introduction

The increasingly complex and globalized nature of many industries coupled with the shift from production supply chains from the developed to developing world has led to a global governance deficit that has resulted in the rise of self-regulation by private firms and associations (CitationBüthe, 2010a; Locke, 2013; Ronit, 2006; Vogel, 2008; Gilad, 2010; Mills & Koliba, 2015). Scholars have long debated the efficacy and effectiveness of shifting from mandatory government-centered regulatory regimes to voluntary private self-regulatory regimes (e.g. CitationAndrews, 1998; Haufler, 2001). Private self-regulation occurs in various forms including standards that are developed by industries and guide governance; codes of conduct and best practices developed by industry associations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs); certification and labels (such as “green” and “triple bottom line” businesses) to develop a reputation for corporate social responsibility (CSR); and voluntary self-disclosure and audit programs to continually improve both efficiency and compliance with best practices and standards (CitationMayer & Gereffi, 2010; Potoski & Prakash, 2009). Scholars have examined several facets of the rise of private governance including the conditions for its emergence and the capacity and performance of private regulation (CitationEberlein et al., 2014; Abbott & Snidal, 2010; Büthe, 2010a; Cutler, Haufler, & Porter, 1999 Citation; Falkner, 2003; Pattberg, 2005). Empirical studies of private governance have examined efforts to regulate and coordinate complex activities across a wide range of domains including forestry, fisheries, financial markets and labor standards in the global south (CitationBartley, 2007, 2014; Cashore et al., 2004; Gulbrandsen, 2014; Porter, 2014).

The literature on voluntary self-audit and self-disclosure programs has largely been centered on the programs individual firms or those organized or implemented by government agencies. Voluntary self-disclosure programs offer firms the opportunity to monitor (through self-audits) and report regulatory violations in exchange for reduced sanctions, confidentiality, or the opportunity to collaborate with regulatory agencies, industry associations, or other firms to develop solutions to address the violations (CitationMills, 2010; Mills & Reiss, 2013). Self-disclosure and self-audit programs benefit both firms and government agencies by reducing compliance costs for firms and enforcement costs for agencies while providing them with secondary information about the level of compliance at specific firms (CitationKaplow & Shavell, 1994; Mills & Reiss, 2013). CitationArlen and Kraakman (1997) and CitationPfaff and Sanchirico (2000) argue that firms are in much better position to self-audit and identify regulatory non-compliance by employees than government agencies, however, firms are often unwilling to do so because of fears that the information on compliance problems they gather and disclose will be used by agencies or adverse private firms in investigations or to cause reputational damage by “naming and shaming”. In their examination of the behavior of firms who self-audit and disclosure violations to the EPA's Audit Policy program, CitationShort and Toffel (2008) found that self-disclosures by firms were often motivated by recent enforcement or inspection activities. Other studies have found that regulators reward firms who participate in self-audit and disclosure programs by reducing the number of future inspections (CitationShort and Toffel, 2011).

A critical question surrounding the development of private governance arrangements to ensure compliance is the role of the state in providing legitimacy and enforcement capabilities (CitationAyres & Braithwaite, 1992; Rees, 1997; Bernstein & Cashore, 2007). Some scholars such as CitationRees (1997) have argued that public enforcement capacity is a necessary precondition for the establishment of private regulatory mechanisms, which Rees referred to as the “regulatory gorilla in the closet” (p. 519). Other scholars argue that private regulatory arrangements emerge as a result of a lack of, or failure of state-based regulatory governance arrangements (CitationAbbott & Snidal, 2009b). A final group of scholars has argued that public and private regulatory actors can benefit from well-designed governance arrangements that complement one another (CitationBlack, 2003; Verbruggen, 2013). Private regulators benefit from the legitimacy provided by public regulatory enforcement agency of self-regulatory programs while public regulators gain access to resources such as information, expertise, financial means, authority, or organizational capacity that the regulator itself might lack (CitationBlack, 2003).

Despite the growing literature on private self-regulation mechanisms such as voluntary disclosure and self-audit programs, we know little about interaction of private self-regulation or its effect on the ability of the public sector to develop similar governance structures. The questions this paper addresses are: How do private self-regulatory programs either fill a vacuum of regulation or complement existing regulatory structures, and how do these programs support or crowd out the development of public regulatory enforcement programs? To answer these questions, this paper develops an empirical case study of voluntary self-disclosure, internal audit, and data analysis programs employed by air carriers and their trade associations to improve their level of safety. Specifically, this paper will examine the development and implementation of two programs operated by the International Air Transport Association (IATA): Safety Trend Evaluation, Analysis & Data Exchange System (STEADES) and the Internal Operational Safety Audit (IOSA) program. The STEADES and IOSA programs, are private self-regulatory programs designed and implemented by the airline industry to proactively identify safety hazards before their become incidents and accidents. The argument advanced in this paper is that when there is a congruence of goals between industry and government, private regulatory programs can complement or even replace existing public sector regulatory regimes. Additionally, this paper argues that private self-regulatory programs can develop to a point where they become a valuable tool for public regulators. Finally, this paper argues that successful self-regulatory programs can often be threatened by competing public programs that aim to replicate self-audit and data exchange programs operated by industry.

This paper makes a significant contribution to the literature on private governance by focusing on an under explored mode of private regulation: voluntary self-audit and disclosure programs. Additionally, the analysis of the case of self-audit and disclosure programs in aviation safety has generalizability to private self-regulation in other “high reliability” industries such as nuclear energy regulation where the acceptable risk for an incident is often zero and a lack of regulatory compliance by one firm can significantly impact the reputation of the entire industry. Finally, the discussion presented in this paper advances our theoretical understanding of private self-regulation by focusing on the interaction between state-sponsored and private voluntary regulatory regimes in a constantly evolving regulatory environment and illustrating how private self-regulatory programs evolve over time. This paper is structured as followed: First, I provide a brief review of the literature on voluntary self-audit and disclosure programs to situate the IATA programs in a broader context. Next, I develop an in-depth case study of the STEADES and IOSA programs operated by IATA. Finally, the paper analyzes the IATA programs by examining the conditions and nature of interactions between private self-regulatory programs and public regulatory programs.

2 Complementary or crowded-out: theorizing the interaction of public and private regulation

A central debate in the literature examining private regulation is the extent to which self-regulatory programs arise as a result of a lack of public governance mechanisms and therefore “crowd-out” the development of comparable public enforcement mechanisms or the ability of private programs complement existing public regulatory programs. Similarly, scholars have examined the ability of CSR efforts to serve as an institutional mirror or substitute for existing public institutional arrangements and found mixed results (CitationGjølberg, 2009; Kinderman, 2012; Koos, 2012). A number of scholars have argued that private regulation has emerged to fill a regulatory void caused by the retraction of the state in the regulation of many sectors (CitationBüthe, 2010a; Cutler et al., 1999; Vogel, 2008). According to these scholars, one of the main effects of the rise of private regulation is to further displace the role of the state in regulatory enforcement. This displacement hypothesis conceptualizes private and public forms of authority as pushing and competing against one another, so that as one rises in importance, it crowds out the other (CitationBartley, 2005; Cutler et al., 1999; Ebenshade, 2004; Fransen, 2011). Another strand of literature argues that state-involvement is necessary for private regulatory arrangements to be effective and legitimate (CitationAyres & Braithwaite, 1992; Rees, 1997; Bernstein & Cashore, 2007). Public regulatory agencies can complement private regulatory arrangements by providing important legitimacy to these arrangements while also signaling to reluctant parties that if they do not comply, they will have to deal with enforcement action from a public agency (CitationVerbruggen, 2013). CitationBlack (2003) argues that private regulatory programs can also complement Given the centrality of the debate of the interaction of public and private regulation, it is critical to identify the factors that affect the ability of private regulation to both complement and crowd-out existing and proposed public regulation.

A key factor in determining the level of competition of complementarity between public and private regulatory programs is the congruence between the goals of the public and private sector actors. In their examination of voluntary self-disclosure and self-audit programs operated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), CitationMills (2010) and CitationMills and Reiss (2013) found that airlines were willing to exchange de-identified safety information contained in disclosure and audit reports with other carriers and the FAA to improve safety across the industry. The authors note that the willingness of airlines to share de-identified data with the FAA and other airlines is due to the fact that the entire airline industry enjoys reputational benefits from having a high-level of safety across all air carriers. CitationMills and Reiss (2013) found that the congruence of goals among regulators and airlines (safety) was a large reason for the success of voluntary disclosure programs operated by the FAA. Therefore,

Proposition #1

In regulatory environments with a high level of goal congruence between firms and regulatory enforcement agencies, private regulatory programs will complement existing public regulatory programs.

The capacity of the public regulatory enforcement agency is another key variable in determining whether private regulation will complement their activities. CitationVerbruggen (2013) argues that in cases where agencies have limited enforcement resources, private regulatory programs can complement public activities by using the data and best practices of private regimes to inform their own course of action. Similarly, CitationMills and Reiss (2013) argue that private self-regulatory mechanisms can provide public regulators with valuable data on areas of non-compliance as well as valuable secondary information on larger firm and industry trends. Therefore,

Proposition #2

Where public regulators have limited enforcement resources, private regulatory programs will complement public enforcement action through increased access to data and resources.

The need for recognition by public actors of private governance programs for the purpose of providing legitimacy is well established (CitationBernstein and Cashore, 2007). However, it may also be the case that states will not recognize private regulatory programs until a sufficient number of private firms have signaled their acceptance of the governance regime. Also, it is likely that public enforcement agencies would only recognize private regulatory programs that complement their existing enforcement actions. If public governance mechanisms are non-existent, then the recognition of private governance driven in large part by acceptance by private actors. Therefore,

Proposition #3

Private regulatory program recognition by states is driven by participation by a large number of firms in private governance programs.

A final variable that determines the interaction of public and private regulatory programs is the level of success enjoyed by the private governance program. In cases where private governance programs become well-established and gain a reputation for effectiveness, there will be a desire by existing public enforcement agencies to use these programs to complement their existing activities. In areas where no comparable public governance regime exists, agencies may face political pressure to develop comparable programs that threaten the success and legitimacy of private governance arrangements (“reverse crowding-out”). It is likely the case that once private programs are established, public regulators would want access to the data from private regulatory programs to enhance their own safety programs. However, access to private regulatory programs may not provide the desired information from industry that regulators seek or may be costly for the regulator to obtain (both in a monetary sense and in terms of missing information in order to ensure confidentiality for reporters). Finally, it is likely that once elected officials become aware of a reliance on private regulatory programs by public agencies through either an aviation crash, hearings, or other means, that they will take action to establish similar programs to avoid the public perception that private industry, not public institutions, are leading the way on safety. Therefore,

Proposition #4a

Where existing public governance regimes exist, successful private regulatory programs will be used to complement existing enforcement programs.

Proposition #4b

If public governance regimes do not exist, successful private regulatory programs may face “crowding out” as public enforcement agencies face political pressure to develop comparable programs.

These propositions will be assessed through analysis of the development and operation of the STEADES and IOSA programs operated by IATA. This article will explore how private self-regulatory programs interact with existing and proposed public regulatory programs and whether this interaction complements, competes with, or crowds-out public regulation.

3 Methodology

To explore the evolution and interaction of IATA's self-regulation programs, this paper relies on a qualitative research design that examines multiple programs using the qualitative analysis tool of process-tracing. Process tracing is the use of histories, archival documents, interview transcripts, and other sources to examine and describe political processes and to test existing causal explanations or to develop new variables or hypotheses (CitationCollier, 2011; George & Bennett, 2005; Tilly, 2001). This paper uses process-tracing to explore the evolution and interaction of IATA's self-regulation programs. Several sources of data were used to construct the description and analysis of the IATA and EASA programs including republished interviews with safety officials, official reports from IATA, safety regulators, and other aviation groups, and other scholarly accounts of self-regulation in the aviation industry.

4 The International Air Transport Association (IATA)

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) is the primary industry association for air carriers around the globe. Founded in 1919 at The Hague as the International Air Traffic Association, IATA has 240 members from 118 nations across the globe. IATA is governed by a Board of Governors (31 members) who approve a Director General of the organization and exercise oversight and a fiduciary role on behalf of the membership as a whole. The Board of Governors is elected by the entire membership of the association during IATA's Annual General Meeting. Over time, IATA has become more concerned with ensuring the financial viability of air carrier and acting as the voice of the airline industry through advocacy and lobbying. Today, the mission of the organization is “to be the force for value creation and innovation driving a safe, secure, and profitable air transport industry that sustainably connects and enriches our world” (CitationIATA 2014). IATA works to achieve this mission through a variety of initiatives and programs that develop policy in diverse areas including safety, environmental sustainability, cargo, security, and operations. The organization has several strategic initiatives including contributing to airline financial health, encouraging partnerships to increase the value of aviation, and to protect the interests of the industry. Additionally, the organization provides a wide-range of services to its members including advocacy, training, business intelligence, financial services, and legal council.

5 IATA Operational Safety Audit (IOSA)

During the mid to late 1990s, many airlines were frustrated with the number and frequency of safety audits they were completing in a given year. Each time an airline wanted to enter into an alliance or code-share agreement with another carrier, the other carriers wanted to ensure that the new entrant was of high quality and had an acceptable level of safety that would not diminish the reputation of the alliance of the carrier (CitationBinder, 2008). In addition to the routine mandatory audits of safety regulators, there were a variety of air carriers and other organizations conducting safety audits using inconsistent standards and practices. Therefore, air carriers were wasting significant resources on audits that were not generalizable to other areas and therefore prevented the sharing of results among other carriers. IATA estimated that overlapping and redundant audits cost airlines over $3 billion during the 1990s (CitationBinder, 2008).

The IATA Operational Safety Audit (IOSA) project was born in February 2001 when the Director General created the IOSA Advisory Group (IAG). The overarching goal of the IOSA project (according to the IAG) was to “formulate and implement IOSA as an internationally recognized evaluation system by which the level of competence and reliability of an airline to deliver a safe operation and manage attendant risks may be assessed” (CitationWoodburn, 2002). Importantly, IOSA was initially seen as a proactive voluntary operational (rather than regulatory) audit program that would complement existing ICAO and civil regulatory audits. One of the first tasks of the working groups was to develop standards and recommended practices that would form the basis of the audits. The task forces relied heavily on the ICAO SARPs and the Air Transport Association's (ATA) standards for code-share operational reviews (CitationBinder, 2008). IATA had to balance concerns regarding the rigor of the audit program. On one hand, the more rigorous that IOSA was, the more costly it may be to both the organization and air carriers to implement. On the other hand, IATA had to make the program rigorous enough to encompass many of the audits it was seeking to replace while also meeting the demands of safety regulators. IATA officials developed a mantra that “every well managed airline would meet the IOSA standards” (CitationWoodburn, 2002). The teams decided that the IOSA Standards and Recommended Practices (ISARPs) would cover the following functional areas:

| • | Organization & Management System. | ||||

| • | Flight Operations. | ||||

| • | Flight Dispatch. | ||||

| • | A/C Engineering & maintenance. | ||||

| • | Cabin Operations. | ||||

| • | Ground Handling. | ||||

| • | Cargo Operations. | ||||

| • | Operational Security (CitationHmelevskis, 2014). | ||||

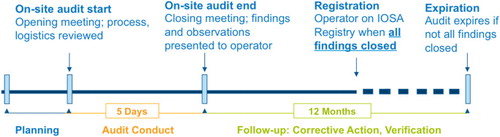

In addition to develop ISARPs, the IOSA task forces established a framework for the audits that outlined how often and who would conduct the audits. IOAS audits are conducted every two years. outlines the IOSA process. Carriers who successfully implement the CAP were added to the IATA registry, which certifies that they successfully completed the IOSA process. Finally, one of the goals of the IOSA program was to foster the exchange of information among carriers and regulators. Therefore, IATA designed an audit findings sharing system that allowed interested parties to view a carrier's audit results as long as the carrier agreed to the request (CitationAnderson, 2003). This sharing system eliminated the needs for redundant or duplicative audits for alliances or code-shares as all air carriers could look at audit findings in a centralized location.

Despite the initial success of the IOSA program, a major challenge for IATA was to gain acceptance and recognition by civil safety regulatory agencies and to demonstrate the value of the program to carriers. In 2004, IATA completed only 39 IOSA audits and had difficulty convincing a large portion of its membership to commit for audits. A boost to IATA's business case for IOSA came in the fall of 2004 when the FAA announced that it would recognize IOSA as an acceptable audit when U.S. carriers add foreign carriers to their alliances or code-share arrangements (CitationSabec, 2004). In 2005, IATA made the decision to waive all IOSA program management fees and make the IOSA Standards freely available to both members and non-members (CitationIATA Annual Report 2005). Another limitation for the expansion of IOSA was that many air carriers in developing nations lacked the awareness and funding to implement IOSA standards. IATA launched its Partnership for Safety in 2005, which made over $3 million (invested by engine and airframe manufacturers) available for air carriers in Africa and Latin America to conduct IOSA audits and reach technical standards (CitationIATA Annual Report 2005). A significant development that led to the expansion of IOSA was ICAO's development of the Safety Management Manuel (Doc 9859) in 2006. The ICAO manual contained guidance for the establishment of Safety Management Systems (SMS)Footnote1 by both civil regulators but also air carriers. As part of ICAO's SMS policy, civil regulators and air carriers were directed to implement self-audit and voluntary reporting programs to proactively identify and address safety gaps in their organizations (CitationICAO Doc 9859). This raised the profile and demand for IOSA as many regulators and air carriers lacked the resources and expertise to implement self-audit programs. As a result of ICAO's SMS guidance, IATA mandated that all of its current members and those applying for membership complete and pass an IOSA audit in 2009. As a result of this mandate, 23 airlines lost their membership to IATA. Additionally, IATA agreed to pay for the total cost of conducting an IOSA audit (Airlines International 2009).

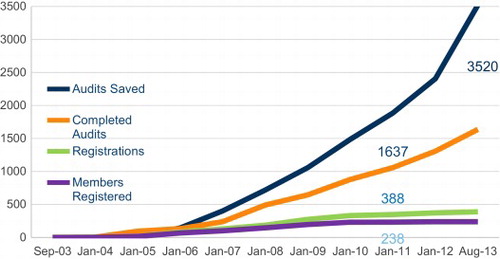

In order to address the challenge of recognition by regulators, IATA took steps to fully integrate SMS by modifying the IOSA audit process and by sharing its audit data with regulators. As air carriers and regulators began to use the IOSA audit as a component of their SMS programs, they noted that the every two-year audit conducted through IOSA was not meeting the requirement for continuous quality assurance audits called for by SMS. In 2013, IATA launched its Enhanced IOSA (E-IOSA) audit program as a revised version of the IOSA audits that called for continual internal auditing by the air carriers for compliance with ISARPs. During their E-IOSA renewal audits of air carriers, the IATA AOs will focus on compliance with select ISARPs and will now audit the internal auditing programs developed by the air carriers (CitationFregnani, 2014). The E-IOSA audit is currently voluntary but will become mandatory in September 2015. In addition to the development of the E-IOSA audit, IATA also worked to develop data-sharing relationships with regulators to further enhance the credibility of the IOSA program while promoting the idea that IOSA complemented, rather than competed with existing state programs (CitationO’Brien, 2008). In 2010, IATA signed a Declaration of Intent to share aggregated IOSA data with the FAA through its Commercial Air Safety Team (CAST) (Airlines International 2010). The organization has also entered into several other data sharing arrangements including one with the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in 2014 that will allow IATA to access EASA's Safety Assessment of Foreign Aircraft (SAFA) in exchange for IOSA audit information (CitationLearmount, 2014). These factors have led to significant growth in the IOSA program. illustrates the growth in the number of IOSA audits from 2003 to 2013. Interestingly, of the 388 IOSA certified air carriers, 150 of them are not members of IATA, suggesting that the IOSA certification has significant value.

Source: IATA Annual Report 2013.

6 Voluntary Safety Data Exchange Programs and Global Aviation Data Management (GADM)

In addition to its IOSA audit program, IATA also operates a suite of voluntary safety data exchange and reporting programs that further the industry's proactive and data-driven approach to identifying incidents before they become hazards and accidents. These data exchange programs are an essential component of ICAO's SMS implementation plan. In 2009, IATA launched its Global Safety Information Center (GSIC), which is a web portal that allows users to conduct safety trend, location, and benchmark analysis of seven data sources including IOSA audits and STEADES. Following the creation of GSIC, IATA joined ICAO, the FAA, and the EU Commission in signing a Declaration of Intent for the enhanced exchange of safety information (IATA 2010). This international recognition led to a dramatic increase in the use and reporting to IATA's programs. Today, over 460 organizations submit data to the GSIC including 90% of IATA's members (CitationIATA Annual Report 2013). In 2013, the organization announced further plans to refine GSIC through the creation of the Global Aviation Data Management (GADM) program. GADM will integrate the GSIC databases with new sources of data including fuel efficiency, aircraft recovery, maintenance cost, and air traffic management efficiency. The expansion of GADM will allow IATA and its members the opportunity to better understand the total costs of incidents and repairs while also improving safety (CitationIATA Annual Report 2013). A cornerstone of IATA's GADM program is the Safety Trend Evaluation and Data Exchange System (STEADES).

6.1 Safety Trend Evaluation and Data Exchange System (STEADES)

STEADES is an aviation safety incident data management and analysis program and is the world's largest source of de-identified incident reports with over 160,000 incident reports from 177 participating air carriers ( ) collected in 2013 (CitationIATA Annual Report 2013). Each quarter, participating air carriers send their de-identified incident reports to IATA. Incident reports are filed by pilots, mechanics, ground personnel, etc. and contain the following data: incident title, date of incident, aircraft type, phase of flight, departure airport, destination airport, event location, risk assessment, narrative summary, and event classification (CitationIATA 2009). Once received in the STEADES system, the data is analyzed to identify trends and areas of potential hazard, which allows IATA and STEADES participants an overview of industry performance and standards while contributing to risk assessment under SMS. Air carriers who contribute to STEADES have free access to STEADES benchmarking and trend reports that allow participants to compare their safety rates and areas of hazards to those of the industry as a whole.

Source: IATA STEADES High-Level Analysis 2014.

While the STEADES program was officially created in October 2001, its history dates back to 1991 with the creation of the British Airways Safety Information System (BASIS). BASIS was an internal non-punitive reporting program established by British Airways and the British Air Line Pilots Association (BALPA) that allowed employees to submit a voluntary (or in some cases a mandatoryFootnote2) incident report to their supervisors without fear of reprisal (CitationDuke, 2001). As is the case in many voluntary reporting programs, the level of reports increased over time as trust between management and employees grew-from 2500 in 1992 to over 8000 in 1999 (CitationDuke, 2001). Due to the success of the BASIS software, many other carriers who had developed voluntary reporting programs approached British Airways about the possibility of sharing de-identified reports through its software to allow for a wider range of safety data across airports and aircraft fleet types (CitationGAIN 2003). This program became operational in 1999 and was known as the Safety Information Exchange (SIE). SIE provided air carriers who contributed reports quarterly analyses of aggregated de-identified safety data. Despite the success of the program in fostering information exchange between carriers, British Airways was concerned about potential legal issues that could arise if a carrier's data were to become public through their system. Therefore, British Airways transferred control of the SIE to IATA in 2001 to form STEADES.

Throughout the 2000s, the number of reports to submitted to air carriers and then to STEADES increased drastically. There are several explanations for the growth of voluntary reporting. First, as trust builds among participants in voluntary programs, the level of reporting also increases-even if the overall number of incidents decreases. This paradox is what often leads groups such as IATA to restrict access to STEADES data to air carriers and safety regulators for fear of misinterpretation by the media and the public (CitationMills, 2010). Trust in voluntary programs is often built through an adherence to non-punitive action, confidentiality, ease of reporting, promotion of findings, and acknowledging the importance of reporting across the industry (CitationMills, 2010; Mills & Reiss, 2013). Second, the growth of STEADES was also tied to the issuance of ICAO Doc 9859, which called for civil regulators and air carriers to establish voluntary reporting programs within their organizations. While many states had voluntary programs prior to the issuance of the ICAO SMS program,Footnote3 the new guidance required that regulators and air carriers integrate the data from these programs into their safety oversight systems. This increased the demand for benchmarks and trends and thus for aggregated safety data provided by STEADES.

The success of STEADES and other public-private data sharing programs such as the Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) program operated by the FAA led the European Parliament to adopt Regulation (EU) No. 376/2014, which directs EASA to establish a voluntary self-reporting and data analysis system similar to STEADES by pooling voluntarily submitted data from Member State safety regulators. In the preamble to the regulation, the Parliament notes that part of the motivation for pursuing a public reporting program was to ensure that safety regulators had access to incident analysis and reporting used by air carriers and to develop a coordinated system that that would allow for the benchmarking of Europe's safety record to that of the rest of the world. Specifically, the European Parliament directed air carriers to “analyze those occurrences that could have an impact on safety, in order to identify safety hazards and take any appropriate corrective or preventive action” and to “send the preliminary results of their analyses to the competent authority of their Member States or to the Agency (EASA) (Regulation No 376/2014 p. 122/19). EASA and Member States were charged with developing “a similar procedure for those occurrences that have been directly submitted to them and should adequately monitor the organization's assessment and any corrective or preventive action take” (Regulation No. 376/2014 p. 122/19). Importantly, the regulation encouraged air carriers to continue their existing mandatory and voluntary reporting systems while developing a complementary system that would satisfy the requirements of the regulation. An interesting component of the regulation was that it charged the European Commission with issuing guidance to air carriers and regulators to ensure the completeness and accuracy of reported information to “prevent a loss of confidence in the information produced” (Regulation No. 376/2014 p. 122/20). Finally, the regulation directed EASA to house the data collected from all voluntary reporting programs in the European Central Repository.

Upon the issuance of the European Parliament regulations, IATA raised several serious concerns about the creation of the new voluntary reporting programs to be run by EASA. One major concern raised by IATA was that air carriers should not be obliged to submit voluntary reports to Member State authorities or EASA because “this would significantly reduce the willingness to voluntary report” (IATA/AEA Position Paper 2014). IATA noted that voluntary reporting programs have been effective in large part because reporters (and air carriers) are confident that their information will be kept within the organization or shared with other air carriers in a de-identified manner. If reporters believe that safety regulators may use the information they provide to take punitive action, then the level of reporting may decrease. Finally, IATA raised concerns about publishing de-identified occurrence reports due to the possibility of misinterpretation by the public. EASA responded to IATA's concerns by seeking to model their voluntary reporting program not after STEADES but rather the FAA's ASIAS program which uses servers located at each carrier's headquarters to house voluntarily submitted data that is queried (in a de-identified fashion) from a remote location (CitationMills, 2010). Patrick Ky, director of EASA, confirmed that he was working with the FAA on the project and noted that he would have a “small voluntary reporting system operational within two years” (CitationGrady, 2014). However, the estimated cost for developing the software and hardware for the system is estimated to cost $200 million. Despite the development of the EASA program, the STEADES program continues to be a robust source of safety information for air carriers to improve their SMS programs.

7 The interaction of private self-regulatory and public regulatory programs

The cases of the IOSA and STEADES programs provide an interesting diversity of factors that have influenced their interaction with public regulatory programs. It is clear from the cases that both IOSA and STEADES were used by public agencies to complement their existing safety enforcement regimes. The high degree of cooperation between industry and the public sphere is often the result of the congruence of goals-in this case, the safety of the airline industry. Air carriers have an incentive to invest in safety oversight as a series of accidents could hurt the reputation and profitability of the industry. While the secondary goal of IATA was to streamline existing regulatory processes, the primary goal of the development of IOSA was to develop an alternative way to ensure the safety of individual air carriers and to share safety information across carriers. Similarly, the creation of STEADES was in large part driven by British Airways’ desire to supplement its safety reporting data with data from other carriers that would allow it to benchmark its performance compared to the industry as a whole. Consistent with the findings of CitationMills and Reiss (2013), the unique convergence of private and public governance in the aviation industry around the goal of safety is a significant factor in the complementary nature of IOSA and STEADES to existing public enforcement activities and provides support for Proposition #1.

A factor that is inherent in the creation of both programs was the lack of intergovernmental institutions that provided a mechanism to engage in self-auditing and voluntary data exchange across the aviation industry. To a large extent, the decision by industry to fund these initiatives was in response to an increase in the global accident rate and a growing public perception in the late 1990s and early 2000s (due to the September 11th attacks) that aviation was unsafe. This led IATA to form its Safety Strategy 2000+ and to the creation of IOSA and STEADES to enhance safety while also working to protect the reputation of industry (CitationHaufler, 2001). At the same time, it was clear that public regulatory agencies lacked the capacity to generate and analyze data on self-audit and self-disclosure programs. As a result, regulators established governance regimes through ICAO to mandate these programs and gain access to the information provided through the programs. Specifically, ICAO established a requirement for an IOSA audit as a part of both an air carrier's and a regulator's SMS. Similarly, ICAO encouraged safety regulators to integrate safety data collected through programs such as STEADES into their oversight mechanisms. This suggests, consistent with CitationBlack (2003) and Proposition #2, that public enforcement agencies use complementary private regulatory programs to enhance their resources for oversight.

Both IOSA and STEADES have experienced an increase in the level of acceptance and participation by air carriers and other aviation organizations. The increase in the use of IOSA by both IATA members and non-members indicates that air carriers see value in the self-audit program that exceeds the benefit of joining IATA. While participation in IOSA did increase as a result of mandating the program for membership in IATA, the increase in air carrier participation is directly linked to the recognition of IOSA as an alternative to civil regulatory agency audits of codeshare or regional partners. Additionally, the issuance of the ICAO SMS guidance led to a drastic increase in air carrier participation. This suggests that domestic and international organizations such ICAO cannot only legitimize private regulatory programs (i.e. CitationBartley, 2007; Cashore, 2002), but can also create conditions through policy change that lead to increased private firm participation in self-regulatory programs. The increased participation in the voluntary reporting program was largely the result of the building of trust between both pilots and management as well as air carriers and safety regulators who have access to de-identified reports from IATA. This supports the findings of CitationMills (2010) and CitationMills and Reiss (2013) who argue that the expansion of voluntary data exchange programs is dependent upon the level of trust build among participants through repeated interaction and adherence to non-punitive corrective action.

The recognition of private self-regulatory programs by states or government agencies provides important legitimacy to these programs that often leads to their growth and evolution (CitationBartley, 2007; Cashore, 2002; Gulbrandsen, 2014). The recognition of the IATA self-audit program by the FAA in 2004 as well as recent data sharing agreements with EASA and CAST has provided legitimacy to the program that has fostered its continued growth. Contrary to the expectation of CitationEbenshade (2004), the IOSA program contains SARPs that exceed the rigor of most ICAO SARPs. The fact that many regulators including the FAA and EASA use IOSA data to inform their safety oversight protocols suggests that industry has devised a self-audit program that is very rigorous. The STEADES program has also received significant recognition from agencies as a valuable safety program for the aviation industry. Many safety agencies rely on data from STEADES to conduct analyses that guide their oversight activities. While some may argue that the IOSA program has crowded-out other government regulatory audit programs, the success and evolution of IOSA and the new E-IOSA program suggest that many domestic and international organizations including ICAO have taken an active role in shaping the future of the audit program and ensuring that it results in a high degree of safety by air carriers CitationRonit, 2008). Therefore, we find mixed support for Proposition #3. While public regulators were more willing to recognize and codify both the audit and reporting programs after the number of participants had marginally increased, only after ICAO had integrated both the private self-audit and voluntary reporting program into the recommended practices did the number of participants increase significantly. This suggests that the legitimacy afforded by public agency recognition and use of private regulatory data sends reputational signals to private firms on the importance and effectiveness of private governance mechanisms.

Finally, IOSA has become a complementary part of both air carrier and public regulatory SMS programs largely because IOSA was a replacement for existing public regulatory audit programs that were largely redundant, consistent with Proposition 4a.

However, the success of STEADES and other voluntary data exchange programs has led to pressure on government agencies to develop their own exchange systems. Much of the desire by members of the European Parliament to design a similar public reporting program to STEADES was largely attributable to the fact that EASA regulators noted that they did not have full access to the data reported by airlines and their employees. The pressure to design a public equivalent of STEADES emerged from the European Parliament's decision to mandate the creation of a competing system to be operated by EASA and illustrates how private self-regulatory programs can be victims of their own success. As the airline industry noted in their opposition letter, the proposed public voluntary program may result in a lack of trust between air carriers and regulatory agencies that has been fostered by the successful implementation of the private reporting program. Also, the EASA program may have the effect of confusing reporters and creating competition among these programs. In essence, the creation of the EASA program may result in the crowding-out of a successful private self-regulatory program. This suggests, consistent with Proposition 4b, that recent demands for increased public involvement and oversight of private self-regulatory programs may undermine existing programs and threaten the ability of regulators to learn from existing private self-regulatory programs.

8 Conclusion

This paper has provided an examination of the interaction between public and private regulatory governance arrangements and the factors that determine whether private regulatory programs compete or complement public regulatory enforcement actions. The case of the aviation industry's experience with the IOSA and STEADES programs support the argument that public recognition of private regulatory programs strengthens the capacity of private programs to ensure compliance and collect and analyze important safety information. Additionally, the cases presented here suggest that the congruence of goals between the private and public sectors as well as the success of the private regulatory program are significant factors in determining whether these programs will complement or crowd-out public regulatory programs. A significant finding from this study is that it is not only public regulatory programs that are at risk of being crowded out. Successful private governance programs that operate in an arena without a comparable public enforcement program generate political pressure for public regulators to emulate and develop a similar program that can crowd-out the successful private program.

The information presented and analyzed in this study is generalizable to several other industries and self-regulatory regimes. Specifically, tracing the development and interaction of IATA's self-regulatory programs allows for the analysis of factors that lead to the development of self-regulatory programs that can be applied to other high-reliability industries. The study of IATA's self-regulation programs allows for an examination of the interaction of industry and government self-regulation programs that is applicable to many high-reliability industries where the reputation of the entire industry can be diminished by one actor who may ignore or not comply with recommended practices. Beyond high-reliability organizations, the findings also suggest that strong alignment of private and public goals are a precondition for the creation of private governance arrangements that complement existing public programs or gain legitimacy from public institutions as valuable regulatory programs. It is likely that that goal alignment is a significant driver of the success of private regulatory programs across a host of industries including food safety, accounting regulation, and environmental monitoring (CitationTosun, 2012).

Another important finding that is transferrable to other industries is that private regulation is most likely to emerge and succeed when it serves the needs of private industry. Specifically, private regulatory programs tend to serve two goals for private industry-they provide information to regulators of responsible firm behavior through reputational signals (thus helping to identify “bad” actors who do mot participate) while also allowing for market expansion and thus potential increases in profitability. While the desire of air carriers to expand their markets was a significant factor in the creation of the IATA internal audit program, it is likely that this motivation exists in industries with private regulatory programs including environmental protection (ISO standards, LEED buildings, etc.) and food safety (beef and chicken labeling, for example). Future research should focus on comparative analyses of industries to compare the conditions under which private regulatory programs develop and how they interact with public regulatory programs.

Notes

* An earlier version of this paper was presented at the workshop ‘The Causes and Consequences of Private Governance: The Changing Roles of State and Private Actors’ held on 6–7 November 2014 at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES). I gratefully acknowledge funding for this event by the COST Action IS1309 ‘Innovations in Climate Governance: Sources, Patterns and Effects’ (INOGOV), MZES, and the Lorenz von Stein Foundation.

1 Safety Management Systems (SMS) refers to a top-down business approach to managing safety risk and includes a systemic proactive approach to managing safety, including the development of internal audit and voluntary reporting programs.

2 The BASIS program had a list of 40 triggering events that required a report to be filed including ground damage, bird strikes, or declaring an emergency.

3 For example, the United Kingdom's Confidential Reporting Program (CHIRP) for aviation has been operational since 1982.

References

- K.W. Abbott , D. Snidal . The governance triangle: Regulatory standards institutions and the shadow of the state. W. Mattli , N. Woods . The politics of global regulation. 2009; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ 44–88.

- K.W. Abbott , D. Snidal . International regulation without international government: Improving IO performance through orchestration. Review of International Organizations. 5 2010; 315–344.

- J. Anderson . IATA operational safety audit. IATA presentation. 2003

- R. Andrews . Environmental regulation and business “self-regulation”. Policy Sciences. 31(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 1998; 177–197.

- J. Arlen , R.H. Kraakman . Controlling corporate misconduct: A comparative analysis of alternative corporate incentive regimes. New York University Law Review. 72 1997; 687–779.

- I. Ayres , J. Braithwaite . Responsive regulation: Transcending the deregulation debate. 1992; Oxford University Press: USA

- T. Bartley . Corporate accountability and the privatization of labor standards: Struggles over codes of conduct in the apparel industry. Politics and the Corporation. 14 2005; 211–244.

- T. Bartley . Institutional emergence in an era of globalization: The rise of transnational private regulation of labor and environmental conditions. American Journal of Sociology. 113 2007; 297–351.

- T. Bartley . Transnational governance and the re-centered state: Sustainability or legality?. Regulation & Governance. 8 2014; 93–109.

- S. Bernstein , B. Cashore . Can non-state governance be legitimate? An analytical framework. Regulation & Governance. 1 2007; 347–371.

- P. Binder . The IOSA story. 2008; VDM Publishers.

- J. Black . Enrolling actors in regulatory systems: Examples from UK financial services regulation. Public Law. Spring issue 2003; 63–91.

- T. Büthe . Private regulation in the global economy. Business and Politics. 12(3): 2010. Articles 1 & 2.

- B. Cashore . Legitimacy and the privatization of environmental governance: How non-state market driven (NSDM) governance systems gain rule making authority. Governance. 15 2002; 503–529.

- B. Cashore , G. Auld , D. Newsom . Governing through markets: Forest certification and the emergence of non-state authority. 2004; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT

- D. Collier . Understanding process tracing PS. Political Science and Politics. 44(4): 2011; 823–830.

- A.C. Cutler , V. Haufler , T. Porter . Private authority and international affairs. 1999; SUNY Press: Albany, NY

- T. Duke . A long standing, successful aviation safety reporting system. Air Line Pilot. January 2001

- J. Ebenshade . Monitoring sweatshops: Workers, consumers and the global apparel industry. 2004; Temple University Press: Philadelphia

- B. Eberlein , K.W. Abbott , J. Black , E. Meidinger , S. Wood . Transnational business governance interactions: Conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regulation & Governance. 8 2014; 1–21.

- R. Falkner . Private environmental governance and international relations: Exploring the links. Global Environmental Politics. 3(2): 2003; 72–87.

- L. Fransen . Why do private governance organizations not converge? A political — Institutional Analysis of Transnational Labor Standards Regulation. Governance. 24 2011; 359–387.

- J. Fregnani . IOSA fundamentals and derivatives. IATA presentation. 2014

- A.L. George , A. Bennett . Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. 2005; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA

- S. Gilad . It runs in the family: Meta-regulation and its siblings. Regulation & Governance. 4 2010; 485–506.

- Global Aviation Information Exchange (GAIN) . A guide to automated airline safety information sharing systems. 2003

- M. Gjølberg . The origin of corporate social responsibility: Global forces or national legacies?. Socio-Economic Review. 7 2009; 605–637.

- M. Grady . FAA, EASA expand safety efforts. 2014. AvWeb http://www.avweb.com/avwebflash/news/FAA-EASA-Expand-Safety-Efforts222180-1.html .

- L.H. Gulbrandsen . Dynamic governance interactions: Evolutionary effects of state responses to non-state certification programs. Regulation & Governance. 8 2014; 74–92.

- V. Haufler . A public role for the private sector: Industry self-regulation in a global economy. 2001; Carnegie Endow. Int. Peace: Washington, DC

- J. Hmelevskis . IATA operational safety audit (IOSA)-SNS Strategy. IATA presentation. 2014

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) . History. 2014. http://www.iata.org/about/pages/history.aspx .

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) . Annual report. 2013. http://www.iata.org/about/Documents/iata-annual-review-2013-en.pdf .

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) . STEADES overview. 2009. http://www.iata.org/services/statistics/gadm/steades/Documents/steades-faq.pdf .

- International Air Transport Association (IATA) . Annual report. 2005. http://www.iata.org/about/Documents/annual-report-2005.pdf .

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) . Safety management manual. Doc 9859-An/474. 2013

- L. Kaplow , S. Shavell . Optimal law enforcement with self-reporting of behavior. Journal of Political Economy. 102 1994; 583–606.

- D. Kinderman . Free us up so we can be responsible! The co-evolution of corporate social responsibility and neo-liberalism in the UK, 1977–2010. Socio-Economic Review. 10 2012; 29–57.

- S. Koos . The institutional embeddedness of social responsibility: A multilevel analysis of smaller firms’ civic engagement in Western Europe. Social Economic Review. 10 2012; 135–162.

- D. Learmount . EASA and IATA to share airline safety data flight global. 2014. April 30.

- R. Locke . The promise and limits of private power: Promoting labor standards in a global economy. 2013; Cambridge University Press: New York

- F. Mayer , G. Gereffi . Regulation and economic globalization: Prospects and limits of private governance. Business and Politics. 12(3): 2010. Article 11.

- R.W. Mills . The promise of collaborative voluntary partnerships: Lessons from the Federal Aviation Administration. Collaborating across boundaries. 2010; IBM Center for the Business of Government: Washington, DC

- R.W. Mills , D. Reiss . Secondary learning and the unintended benefits of collaborative mechanisms: The Federal Aviation Administration's Voluntary disclosure programs. Regulation & Governance. 2013 10.1111/rego.12046.

- R.W. Mills , C.J. Koliba . The challenge of accountability in complex regulatory networks: The case of the deepwater horizon oil spill. Regulation & Governance. 2015 10.1111/rego.12062.

- M. O’Brien . IATA strategy for the future/IOSA. Presentation. 2008

- P. Pattberg . What role for private rule-making in global environmental governance? Analyzing the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). International Environmental Agreements. 5 2005; 175–189.

- A.S.P. Pfaff , C.W. Sanchirico . Environmental self-auditing: Setting the proper incentives for discovery and correction of environmental harm. Journal of Law Economics and Organizations. 16 2000; 189–208.

- T. Porter . Technical systems and the architecture of transnational business governance interactions. Regulation & Governance. 8 2014; 110–125.

- M. Potoski , A. Prakash . Voluntary programs: A club theory perspective. 2009; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA

- J.V. Rees . Development of communitarian regulation in the chemical industry. Law Policy. 19(4): 1997; 477–528.

- K. Ronit . International governance by organized business: The shifting roles of firms, associations and intergovernmental organizations in self-regulation. W. Streeck . Governing interests: Business associations facing internationalization. 2006; Routledge: London 219–241.

- K. Ronit . Financial services and the out-of-complaints bodies in the European Union. J.-C. Graz , A. Nölke . Transnational private governance and its limits. 2008; Routledge: London 196–208. (ECPR Studies in European Political Science; No. 51).

- L. Sabec . FAA approves IATA's operational safety audit (IOSA Program: A historical review and future implications for the airline industry). Transportation Law Journal. 32 2004; 1–20.

- J.L. Short , M.W. Toffel . Coerced confessions: Self-policing in the shadow of the regulator. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 24(1 Co-governance of Common Goods): 2008; 45–71.

- J.L. Short , M.W. Toffel . Coming clean and cleaning up: Does voluntary self-reporting indicate effective self-policing?. Journal of Law and Economics. 54(3): 2011; 609–649.

- C. Tilly . Mechanisms in political processes. Annual Review of Political Science. 4 2001; 21–41.

- J. Tosun . Environmental monitoring and enforcement in Europe: A review of empirical research. Environmental Policy and Governance. 22 2012; 437–448.

- P. Verbruggen . Gorillas in the closet? Public and private actors in the enforcement of transnational private regulation. Regulation & Governance. 7 2013; 512–532.

- D. Vogel . Private global business regulation. Annual Review of Political Science. 11 2008; 261–282.

- P. Woodburn . Safety management systems: Challenges and benefits. IATA presentation. 2002