Abstract

Since the uprising in Syria in March 2011, over 4.3 million Syrians have fled to neighboring countries. Over a million have sought refuge in Lebanon, constituting almost a quarter of the Lebanese population and becoming the largest refugee population per capita in the world.

With inequitable health coverage being a longstanding problem in Lebanon, Syrian refugee women’s health, and specifically their sexual and reproductive health, is disproportionately affected. An increase in gender-based violence and early marriage, a lack of access to emergency obstetric care, limited access to contraception, forced cesarean sections, and high cost of healthcare services, all contribute to poor sexual and reproductive health.

In this commentary, we conceptualize violence against Syrian refugee women using the ecological model, exploring the intersections of discrimination based on ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status, while critiquing interventions that focus solely on the intrapersonal level and ignore the role of microsystemic, exosystemic, and macrosystemic factors of negative influence. These social determinants of health supersede the individual realm of health behavior, and hinder women in taking decisions about their sexual and reproductive health.

Résumé

Depuis le soulèvement en Syrie en mars 2011, plus de 4,3 millions de Syriens ont fui dans les pays voisins. Plus d’un million d’entre eux ont cherché refuge au Liban. Ils représentent près d’un quart de la population libanaise, soit la plus importante population réfugiée par habitant au monde.

L’inégalité de la couverture sanitaire est un problème de longue date au Liban et la santé des réfugiées syriennes, en particulier leur santé sexuelle et génésique, en est affectée de manière disproportionnée. Une augmentation de la violence sexiste et des mariages précoces, le manque d’accès aux soins obstétricaux d’urgence, l’accès limité à la contraception, les césariennes forcées et le coût élevé des services de soins sont autant de facteurs qui contribuent à une mauvaise santé sexuelle et génésique.

Dans ce commentaire, nous conceptualisons la violence à l’égard des réfugiées syriennes avec le modèle écologique, en explorant les intersections de la discrimination fondée sur l’ethnicité, le sexe et le statut socio-économique, tout en critiquant les interventions qui se centrent uniquement sur le niveau intrapersonnel et ignorent le rôle des facteurs microsystémiques, exosystémiques et macrosystémiques d’influence négative. Ces déterminants sociaux de la santé supplantent le domaine individuel des comportements de santé et entravent les femmes dans leurs décisions de santé sexuelle et génésique.

Resumen

Desde el levantamiento en Siria en marzo de 2011, más de 4.3 millones de sirios han huído a países vecinos; más de un millón de ellos han buscado refugio en Líbano, constituyen casi una cuarta parte de la población libanesa y han pasado a ser la mayor población de refugiados per cápita del mundo.

Dado que la cobertura injusta de salud es un problema en Líbano desde hace mucho tiempo, la salud de las mujeres sirias refugiadas, en particular su salud sexual y reproductiva, se ve afectada de manera desproporcionada. Un aumento en la violencia de género y el matrimonio temprano, la falta de acceso a cuidados obstétricos de emergencia, el acceso limitado a métodos anticonceptivos, cesáreas forzadas y el alto costo de los servicios de salud, todos estos contribuyen a una salud sexual y reproductiva más deficiente.

En este comentario, conceptualizamos la violencia contra las mujeres sirias refugiadas por medio del modelo ecológico y exploramos las intersecciones de la discriminación basada en etnia, género y estatus socioeconómico, a la vez que criticamos las intervenciones que se enfocan exclusivamente en el nivel intrapersonal e ignoran el rol de los factores microsistémicos, mesosistémicos y macrosistémicos de la influencia negativa. Estos factores determinantes sociales de la salud reemplazan el ámbito individual del comportamiento relacionado con la salud y dificultan que las mujeres tomen decisiones sobre su salud sexual y reproductiva.

Introduction

Since the uprising in Syria in March 2011, over 4.3 million Syrians have fled to neighboring countries, of whom over a million sought refuge in Lebanon.Citation1 The number of Syrian refugees in Lebanon constitutes almost a quarter of the Lebanese population, which now hosts the largest refugee population per capita in the world.Citation2 Most victims of the conflict are civilians, a majority of whom are women and children.Citation3 In addition to being exposed to war and conflict, they are currently also deprived of the most basic needs, such as food, water, housing, education, healthcare, and protection.Citation4

The experience of Syrian refugee women in Lebanon, facing institutionalized multi-systemic violence, is often lost in a reductive analysis of women in war and gender-based violence (GBV). Sexist, classist, and racist political agendas on the part of the hosting community, governmental institutions, and healthcare systems, as well as women’s own interpersonal circles, are rarely addressed as underlying culprits negatively impacting Syrian women’s sexual and reproductive health (SRH).Citation5

Syrian refugee health in Lebanon

Even before the influx of Syrian refugees, the Lebanese public healthcare system was structurally weak, focusing solely on the provision of services while playing an insufficient role in prevention, planning, and accessibility. The Ministry of Public Health has spent over 54% of its national budget on the private healthcare industry, which has led to a majority of Lebanese citizens paying out-of-pocket.Citation6 Already inaccessible and unaffordable, the Lebanese public healthcare system was unprepared to accommodate large numbers of refugees.

Primary and secondary healthcare is currently available for Syrian refugees, but includes making out-of-pocket payments which most refugees cannot afford. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) covers 75% of the cost of life-saving emergency treatments, delivery, and newborn care, and a few patients manage to get non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to reimburse the remaining 25%.Citation7 Meanwhile, as Syrian refugees struggle to pay healthcare bills, hospitals in Lebanon have resorted to aggressive methods such as withholding corpses, holding newborns hostage, or confiscating personal IDs as a measure to enforce payment of the remaining 25% from refugees.Citation8

Syrian refugee women are disproportionately affected by the situation in Lebanon, due to the increase in GBV (particularly intimate partner violence (IPV), early marriage, transactional sex, sexual assaults), as well as lack of access to emergency obstetric care, limited access to contraception,Citation9,10 forced cesarean sections,Citation3 and the high cost of healthcare services. These factors lead to fewer antenatal care (ANC) visits, delayed family planning, and all round poorer reproductive health.Citation9 Women are also at risk of stress-related mental disorders due to war, trauma, and displacement. Harassment and rape continue to take place in refugee camps, and early marriage is seen as a means of keeping daughters safe and protecting them from poverty.Citation10

The social ecological model of violence prevention

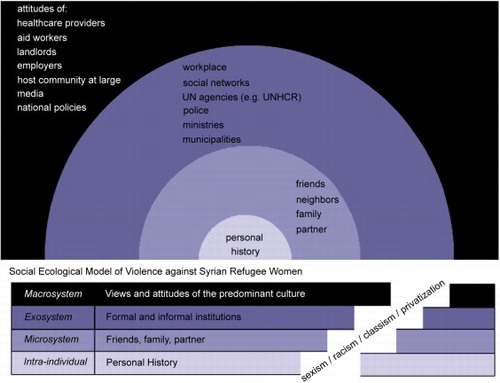

The social ecological model takes into account multiple levels of influence on health behavior, emphasizing how individual, contextual, and sociocultural factors play out in creating a situation of inequitable health for marginalized populations.Citation11 In this commentary, we rely on Heise’s approach to the ecological model, which she has used to conceptualize violence against women (VAW).Citation12 Within this framework, violence is perpetuated through four multilayered factors. The first is the intra-individual level, or one’s personal history, which influences one’s health behavior. The second is the microsystem, or one’s immediate context, such as interactions with friends, family, and partners. The third is the exosystem, which in this case includes all the formal and informal institutions that influence Syrian refugee women’s health behavior, such as their work context, social networks, UNHCR and the humanitarian aid system, the police, and the policies adopted by the Ministry of Health and municipalities in Lebanon. Finally, the fourth factor is the macrosystem, which represents the views and attitudes predominant in the culture.

In this commentary, we are concerned with the attitudes of healthcare providers, aid workers, landlords, employers, and the host community at large, all of which are influenced by the media and national and local policies (see ). The current paper elaborates on the micro-, exo-, and macro-system factors, and the ways in which they interact to negatively impact the health of Syrian refugee women in Lebanon. Rather than focusing solely on the intra-individual level, this model provides a comprehensive approach to understanding the health behavior of these women, while broadening the options for interventions.Citation11,14 In examining sexual assault, for example, Sallis et al argue that framing the impact of sexual assault simply from a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) perspective, or any other trauma model of rape, risks pathologizing the victim and perpetuating ethno-cultural biases.Citation11 Therefore, the utilization of the social ecological model helps us keep in mind that VAW does not occur in a social and cultural vacuum. It is a matter of social injustice rather than solely an individual wrong – where society at large, from the micro-level to the macro-level, makes these acts possible and even acceptable.Citation12,13 The utility of such a model provides multiple levels of intervention and analysis for shifting the focus and blame off the victim and onto the pervasiveness of larger systems.Citation13

This commentary reflects the observations of two Master’s level graduates, in Sexual and Reproductive Health Research (RY) and Social Psychology (CM), who have worked for over the last two years within a local NGO that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), sexuality, and gender in Lebanon. Through phone and face to face interviews via the NGO’s SRH referral hotline with over 300 Syrian refugee women, and based on interactions with other local and international NGOs and healthcare providers, it was apparent that often the interventions targeting the SRH of Syrian women need to address structural obstacles rather than dwelling on intrapersonal interventions. In this commentary, we examine how the social ecological model can highlight institutionalized violence and, specifically, violence against Syrian refugee women in Lebanon and illustrate the multitude of factors (i.e. microsystem, exosystem, and macrosystem factors) which impact their SRH.Citation13,14 These social determinants of health supersede the intrapersonal realm in hindering the choices women have in taking decisions regarding their SRH.Citation5 We will solely be investigating systemic violence against Syrian women’s bodies, whilst recognizing that other refugees – Palestinian, Sudanese, Iraqi, and Kurdish – living in Lebanon also face harsh realities impacting their health.

Microsystemic level - The interpersonal is very political

Interventions targeting Syrian refugee women largely target the intra-individual level, while there are many contextual factors, ranging from the micro- to the macro-levels that need to be taken into account to create any tangible change in their health behavior. The health of the individual is highly linked to their interactions with their partners, immediate family members, extended family, friends, neighbors, and representatives of the exosystem such as healthcare providers and landlords. This can be a supportive or stressful source for the individual refugee,Citation5,14 influencing seemingly mundane decisions that play a pivotal role in health-related decisions. Gendered power imbalances greatly affect women’s SRH, because men dictate and influence women’s mobility, access, and even choice of healthcare procedures and treatment.

The majority of Syrian refugees in Lebanon live in extremely poor and increasingly crowded conditions with extended family members.Citation9 Effectively, privacy is reduced and anxiety enhanced, while women’s health decisions become matters decided by residing family members as well as spouses. Trying to cope and fulfill traditional gender roles, women prioritize the needs of their husbands and children instead of their own health.Citation10 Shifts in gender roles within the family are apparent with men who are bound to the camps or homes due to fear of deportation as a result of illegal entry to Lebanon, or who suffer the physical or psychological wounds of post-war trauma. Meanwhile, frustrated husbands, who due to various reasons cannot assume their gender roles as primary breadwinners, further interfere with women’s mobility and decisions regarding contraceptive choices.Citation10 Within such a restrictive environment, women often find themselves looking for employment while burdened by childcare and unpaid domestic work. Such shifts in gender roles are associated with an increase in Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and hyper-masculinity.Citation10

The Exosystem level: Inhospitable hospitals, laws, and policies

Having fled Syria seeking safety, Syrian refugees’ security is still threatened by racism, discrimination and daily violence.Citation10 At the exosystem level, many Syrian women report violence and exploitation by the hosting community’s landlords, employers, and the police.Citation10 The situation is particularly dire for female-headed households as unmarried or recently widowed women are more vulnerable to inappropriate sexual advances from men offering financial and material assistance in exchange for sex.Citation10 Regardless of their marital status, Syrian mothers seeking refuge in Lebanon are in charge of child rearing and care-taking, a responsibility that takes priority over their own health needs. In Syria, they could resort to family and friends to look after their children, or would trust leaving them at home while seeking healthcare. In Lebanon, the host community, including disgruntled landlords, frown upon the children of refugees playing in the streets,Citation15 and with the steep cost of rent and real threat of eviction, women are more confined to the home and to accompanying their children at all times – enforcing gender stereotypes that perceive women only as fulltime mothers. In other instances, parents forbid their children to play on the streets unescorted for fear of harassment and sexual abuse.Citation10

Additional exosystem factors include formal social systems for assistance such as the Ministry of Health, humanitarian aid agencies, UNHCR, criminal justice system, and the media. A case in point of institutionalized violence against Syrian refugee women in Lebanon, is the practice of UNHCR, which contracted private third party administrators (i.e., private insurance companies such as GlobeMed and MediVisa) to manage secondary and tertiary care referrals for Syrian refugees.Citation7 In effect, many procedures, whether emergency or not, do not get the partial coverage of UNHCR and a search for charity organizations to cover or refund costs becomes in itself a barrier to care for Syrian refugees. Without any sort of representation or voice, and waiting in limbo for something to change, Syrian refugees have lost solidarity with each other because they have ended up competing with each other over aid.Citation16

The inefficiency of the humanitarian aid system becomes apparent when barriers to SRH services for Syrian women appear, mostly, at organizational and community levels. Examples include high cost, distance and transport, fear of mistreatment by aid workers or healthcare providers, security concerns, shame, unavailability of a female doctor, and insufficient provision of services.Citation9 Based on our observations, the situation of Syrian refugees in Lebanon highly resembles that of those in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, where women report multiple barriers to seeking healthcare, which in any case is perceived to be of poor quality. These barriers include long waiting lines, disrespect by healthcare providers, particularly towards women, lack of female doctors, lack of medication, cost of medication, and an unclear referral system. As one women reported, “You stand in line a long time. The [agency] call your name, and if you do not hear them or if you complain, they simply shred your papers and go to the next person.”Citation17

In Lebanon, Syrian refugee women are criticized by healthcare providers for the number of children they have and for the unintended and intended conceptions that took place on Lebanese land. The healthcare providers and humanitarian aid workers do not realize that in Syria, public provision of education, healthcare, and social welfare allowed parents to have more children without worrying about providing their children with the basics in standards of living; a completely unrecognizable reality to a majority of Lebanese citizens who struggle with the privatization of public goods and a feeble welfare system.Citation6,18 Today in Lebanon, Syrian women are struggling to find free or affordable reproductive healthcare, and are mistreated for being pregnant.Citation3,18 A lower percentage of women are found to be using family planning methods (34.5%),Citation9 compared to before the conflict in Syria (58.3%).Citation19 Before 2000, pro-natalist policies in Syria incentivized multi-parity, and up to today family planning services are free of charge and widely available.

By the time women negotiate their interpersonal barriers to seeking health and muster courage to face anticipated institutional violence, and below-par treatment from aid workers, they arrive at their family planning appointments to find out that they are already pregnant and that termination of pregnancies (ToP) is rejected by health providers.Citation20 Syrian women report that they have opted for a ToP while being reviewed by UNHCR for asylum relocation outside of Lebanon, while others believed that having more children would help their chances of receiving cash, shelter, or non-food items support by UNHCR.

Women recount being rejected from hospitals while in labor, either because of lack of finances, or shortage of delivery beds or neonatal intensive care incubators. Even in the case of hospital admission, negligence, low standards of care, and blatant racism are experienced. Many women stated that, during delivery, healthcare workers ignored them for hours, while others said they felt obliged to have C-section because doctors did not want to wait on them in labor and three quarters of their bill would anyway be covered by UNHCR.Citation21 C-section rates among Syrian refugees (35%) are triple the recommended WHO rate, and more than double the rate in pre-conflict Syria (15%).Citation3,21,22 After hospital discharge, a number of UNHCR-registered patients still have to fight for 75% of their hospital bill to be covered if they had to deliver at a non-UNHCR contracted hospital.Citation21

As these stories circulate among women, pregnant refugees fear giving birth in Lebanon. A midwife working at Médecins Sans Frontières states that the high cost of delivering in Lebanon has rendered it common for Syrian women to go back to war-torn Syria to deliver for free.Citation20 Assuming they are aware of and have access to the services designed for them in Lebanon, most of the time they cannot cover 25% of the childbirth costs that UNHCR requires them to cover.Citation20 Of those not heading back to Syria, some women deliver in informal tented settlements, or, if they do go to a hospital, their refugee cards are confiscated until they can pay the medical bill, thus preventing them from getting their food vouchers. According to this midwife, Syrian women do not want to get pregnant, but it is difficult for them to get access to contraception.Citation20 Indeed, two studies assessing antenatal care attendance and C-section rates among Syrian refugees in Lebanon found that less than half of the women in the study wanted their current pregnancies, while also finding a decrease in antenatal care attendance and contraceptive use due to lack of access or availability of the desired contraceptive method.Citation21,23

Macrosystem influences: the adhesive to micro- and exo- systemic violence

It is particularly difficult for Syrian women to report harassment or rape due to the severe social stigma they are likely to face, which might lead to exclusion by family members and society at large.Citation24,25,26 In patriarchal societies where honor crimes are still the norm, women are blamed for the invasion of and violence on their bodies. For example in Jordan, when Iraqi refugees reported sexual violence, more than half of the rape victims were killed by family members.Citation27 In addition, the Lebanese authorities are making it increasingly difficult for Syrian refugees to renew their residencies, putting refugees at risk of arbitrary arrests, detention, and deportation, making it even more difficult for women to report rape.Citation28 This leads some Syrian women to quit their jobs or not take a particular job because their managers harassed them, instead of reporting the harassment.Citation29 In most instances, when women do report the harassment, they become a target of harassment by the police as well.Citation29 Syrian refugees face widespread discrimination by Lebanese authorities and residents, and describe being afraid to report harassment and suffer further abuse or have their stories dismissed by security forces.Citation26 Lebanese authorities do not prevent or persecute the violence directed at Syrian refugees. In fact, the Lebanese government has worsened the situation by mandating evening curfewsCitation15 and a historically unprecedented annual US$ 200 residency permits for Syrians to stay in Lebanon, without which, refugees are subject to arrests and deportation.Citation28 Those who are sexually harassed by landlords, employers, community members, or even aid workers, fear reporting the incidents to the police because of a lack of trust in the security forces or fear of deportation.Citation30 All of these factors limit women’s mobility, thus restricting their access to emergency and routine healthcare facilities, factors that likely contribute to Syrian women’s’ poor reproductive health outcomes.Citation9

Meanwhile, Lebanese citizens are faced with the dominant discourse of the ruling political elite, along with their media, who scapegoat refugees and blame them for all the social, economic, and security problems of the country, further exacerbating resentment towards Syrian refugees.Citation31 Lebanese media depicts Syrian refugee women as “stealing the men” or being “cheap wives” for accepting lower dowry, leading to further harassment, shaming, and bullying of refugees from the host community.Citation32

A number of unmarried women (whether widowed, divorced, or single) have reported sexual violence and feeling particularly vulnerable.Citation10 This elucidates the ways that heteropatriarchy delineates marriage as protective from the physical and sexual harassment of strangers. In Lebanon, this leads many women to (re)marry into abusive relationships or polygamous marriages, a situation similar to that of Iraqi refugees fleeing to Jordan.Citation27 Although they know that the living conditions for them or their children will not improve, they seek the social protection provided by marriage. In the Middle East and North Africa, unmarried women’s SRH needs, in and out of times of war, is traditionally absent from data collection, discussions, and interventions. For example, an international organization working with Iraqi refugees in Jordan prevented access to maternal health services to pregnant women who did not have a marriage certificate.Citation27 According to UNFPA, unmarried women in developing countries face the pressure of dealing with a “socially unsanctioned” pregnancy, which increases their vulnerability.Citation33

The situation is especially dire in Lebanon for Syrian women seeking to terminate their pregnancies. In Lebanon, where abortion services are legally restricted to saving a woman’s life, finding an underground abortion provider usually requires time, effort and money. Women have reported enduring verbal abuse and harassment by healthcare providers who berate them for irresponsibly having unwanted pregnancies and as “bad” women and mothers for wanting to terminate their pregnancy. Meanwhile unmarried women have reported being dismissed by physicians and being told to return with their husbands; such demands do not constitute formal protocols but reflect an authoritarian patriarchal medical response. This verbal abuse does not stipulate that healthcare providers will not provide outlandishly expensive abortion servicesCitation34; it just means that women, constricted with time, will not be able to seek better treatment. Financially-dependent Syrian refugee women often attempt to convince their partners of the long term benefits of the costly termination, a discussion that often becomes one for the entire residing extended family. In many situations, extended family members prevent abortion under the pretext of replacing a family member who died in Syria.Citation18 We have observed that in post-abortion care, women who have prolonged bleeding due to incomplete abortions, for example, tend to postpone seeking medical care and hope the situation will self-resolve. Asking friends, neighbors, and family to step in is not possible for many women who have lost support networks in relocation, or who prefer not to ask for burdensome favors from other women. It is not until the prolonged bleeding or hemorrhaging affects their health and interferes with their roles and responsibilities that they rush to healthcare.

The myth of change via intrapersonal interventions

Often in healthcare, the self is seen as an isolated entity, and illness as caused by internal shortcomings. As such, treatments and interventions are directed at the individual. In this paper, however, we argue that the reasons for not receiving care fall outside the individual, and macrosystemic factors need to be accounted for to fully understand the health seeking behavior of refugees. This is particularly the case when tensions between individual agency and institutional constraints rise from gendered expectations established by the micro-, exo-, and macro-system levels.Citation5

Syrian women distrust NGOs and INGOs, saying that aid workers, often young and untrained, do not understand their contexts and needs, their reasons for not using contraception and that they often talk at them rather than with them.Citation18 Moreover, humanitarian aid barely provides sufficient levels of help, and it does not promote refugees’ self-sustainability, nor does it provide economic, social or political agency.Citation16 Some women attend reproductive health awareness sessions to collect giveaways and hygiene kits. With the influx of funding, a number of NGOs and INGOs direct efforts at awareness sessions, mostly targeting Syrian women who are assumed to be available and easier to reach than men. Such programs reinforce a burdensome gendered expectation that sanitation and the family’s health falls on their shoulders.

This decontextualization of systemic violence and its portrayal as an intrapersonal issue reappears in interventions aimed at reducing the rates of early marriage, and in massively funded psychosocial and mental health programs. The former aims at educating parents on the negative health effects of early marriage on girls, where interventions frame the issue under GBV or lack of awareness rather than poverty. Importantly, such programs do not attempt to change or challenge the social factors and fail to recognize that girls were not married off at such a young age in Syria.Citation32 The latter is used as a substitute for not being able to make effective changes at any larger level than the intrapersonal, where instead of implementing programs to make refugee camps safer from sexual harassment for women, mental health programs become ready to receive women after the fact. Moreover, some NGOs and INGOs offer mental health counseling to women wishing to have an abortion to help them cope with the unwanted pregnancy. Such strategies targeting the intrapersonal hold the oppressed responsible while, from an ecological perspective, it’s recommended that they aim at challenging existing power dynamics in social relationships and norms.Citation14

At the exo- and macro- system level, civil society in Lebanon cannot keep treating Syrian refugees from a strictly humanitarian lens. It must counter prevailing discourses inciting hatred, all the while facilitating refugees’ (and specifically women’s) entry into the discussions of political structures where their representation can help ensure their issues are on stakeholders’ agendas.Citation16 Simultaneously, research and interventions have ignored women refugees' voices, taking superficial gender-related indicators that are either UN- or funder- approved. These indicators miss out the complex and multilayered narratives of women and how they fight sexisms as well as racism, classism, nationalism-induced hatred and costly privatizations of the most basic health services through various inequitable institutions and structures that claim to host them.Citation5

Shifting the framework of interventions and alleviating intrapersonal burdens

NGOs and other civil society actors could assist in creating spaces for Syrian women to meet and organize at a grassroots level. This attempt at re-establishing a solidarity network could help women support each other at a variety of activities: setting up daycare so that they can attend their healthcare appointments, sharing information on the existing SRH referral systems, designing measures of enhancing security from sexual violence at the camps by checking-in on one another, thus enabling each other to speak up, report, or document the violence they face. Being confined to the home, having to carry the responsibility of the household, with a sole dependency on humanitarian aid without a sustainable alternative, and being singled out for mental health counseling, enable patriarchal dynamics that make the issues facing refugees seem like personal problems; all the while hindering the formation of wider sisterhood-based solidarity networks. Women are not able to find the time, space, or energy to organize against these multi-systemic levels of oppression. The interventions are geared towards an “every woman for herself” struggle, while history has shown time and time again that the vulnerable are less vulnerable when they stand together against common struggles.

The Lebanese government and its respective ministries need to learn from their previous experiences with Palestinian refugees; pretending an influx of refugees is a temporary issue only leads to further marginalization, racism, violence, and the denial of the right to live in dignity. Revoking punitive laws enforces respect and harmonious living with the hosting community. The right to work, study, live in a home that is not a refugee camp, and be free from arbitrary arrests and deportation alleviates the violence that Syrians, and specifically Syrian women, face daily. Alleviating these daily hindrances makes women more likely to seek antenatal care, use contraceptive methods, find sympathetic abortion providers, and look after their SRH and the wellbeing of their sisters and wider communities.

It is crucial that we admit that policies, interventions, and the restrictions implemented by all these wider systems, whether via negligence, ignorance, or mis-strategization, can be violent to Syrian women’s bodies and SRH. INGOs and NGOs must think past their indicators and avoid placing the burden of change on refugees, and challenge the macrosystems that propagate these systems of oppression. Designing interventions that target microsystemic, organizational, institutional, environmental, economic, and policy levels, plays a pivotal role in enhancing refugee health behavior, while keeping in mind that changes in the social environment will produce changes at the individual level. Therefore, we hold that a systemic change is required to improve the health and alleviate the burden and multi-systemic blame of Syrian refugee women.

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Syria Regional Refugee Response. 2015. Accessed December 2nd, 2015http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=122

- ACTED. Lebanon: Host of the largest per capita refugee population in the world. http://www.acted.org/fr/node/10124. 2014

- UNHCR. Multi Sector Needs Assessment team (MSNA). Public Health chapter. Syria Regional Refugee Response Inter-agency. Information Sharing Portal. https://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=5397. 2014 April 22

- European Commission. Humanitarian aid and civil protection. http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/aid/countries/factsheets/syria_en.pdf. 2015

- S. Guruge, N. Khanlou. Intersectionalities of influence: researching the health of immigrant and refugee women. CJNR. 36(3): 2004; 32–47.

- N. Salti, J. Chaaban, F. Raad. Health equity in Lebanon: a macroeconomic analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health. 9(11): 2010

- Z. Ammar. Health Response Strategy: A New Approach in 2016 & Beyond. 2015 December 14; Ministry of Public Health. http://www.moph.gov.lb/AboutUs/strategicplans/Documents/HRS-DRAFT8.pdf.

- M. Sidahmed. Syrian refugees buckle under health care bills in Lebanon. The Daily Star. http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2015/May-30/299828-syrian-refugees-buckle-under-health-care-bills-in-lebanon.ashx. 2015 May 30

- A.R. Masterson, J. Usta, J. Gupta. Assessment of reproductive health and violence against women among displaced Syrians in Lebanon. BMC Women’s Health. 14(25): 2014

- R. El-Masri, C. Harvey, R. Garwood. Shifting sands: changing gender roles among refugees in Lebanon. Joint research report. 2013. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/rr-shifting-sands-lebanon-syria-refugees-gender-030913-summ-en.pdf.

- J.F. Sallis, N. Owen, E.B. Fishe. Ecological models of health behavior. K. Glanz, B.K. Rimer, K. Viswanath. Health behavior and health education. 4th edition, 2008; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, 465–486.

- L. Heise. Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 4(3): 1998; 262–290.

- R. Campbell, E. Dworkin, G. Cabral. An ecological model of the impact of sexual assault on women’s mental health. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 10(3): 2009; 225–246.

- K.R. McLeroy, D. Bibeau, A. Steckler. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 15(4): 1988; 351–377.

- Human Rights Watch. Lebanon: rising violence targets Syrian refugees. http://reliefweb.int/report/lebanon/lebanon-rising-violence-targets-syrian-refugees. 2014 September 30

- Y. Al-Saadi. Restrictions, perceptions, and possibilities of Syrian refugees’ self-agency in Lebanon. 2015; Civil Society Knowledge Center: Lebanon Support. http://cskc.daleel-madani.org/content/restrictions-perceptions-and-possibilities-syrian-refugees-self-agency-lebanon.

- United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees. Reproductive health services for Syrian refugees in Zaatari refugee camp and Irbid city. https://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=4108. 2013 March 17-22

- Tabbah M. Who are you to plan our families?. Women Living Under Muslim Laws. 2015 http://www.wluml.org/ar/media/%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A3%D9%86%D8%AA%D9%85-%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%B8%D9%85%D9%88%D8%A7-%D9%86%D8%B3%D9%84%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%9F.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Syrian Arab Republic: monitoring the situation of children and women. http://www.childinfo.org/files/MICS3_Syria_FinalReport_2006_Eng.pdf. 2006

- Médecins Sans Frontieres. Syrian refugees in Lebanon: “Pregnant women often have no idea where to go”. http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/news-stories/field-news/syrian-refugees-lebanon-pregnant-women-often-have-no-idea-where-go. 2013 August 06

- K.M.J. Huster. Patterson N, Schilperoord M, et al. Cesarean sections among Syrian refugees in Lebanon from December 2012/ January 2013 to June 2013: probable causes and recommendations. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 87(3): 2014; 269–288.

- M. Khawaja, N. Choueiry, R. Jurdi. Hospital-based caesarean section in the Arab region: an overview. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 15(2): 2009; 458–469.

- M. Benage, G. Greenough, P. Vinck. An assessment of antenatal care among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Conflict and Health. 9(8): 2015

- L. Davis. Syrian women refugees: out of the shadows. Faculty Publications and Research. http://academicworks.cuny.edu/cl_pubs/54. 2015

- Al-Akhbar. HRW: Syrian refugees in Lebanon face increasing violence. http://english.al-akhbar.com/content/hrw-syrian-refugees-lebanon-face-increasing-violence. 2014 September 30

- Human Rights Watch. Lebanon: women refugees from Syria harassed, exploited. https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/26/lebanon-women-refugees-syria-harassed-exploited. 2013 November 26

- S. Chynoweth. The need for priority reproductive health services for displaced Iraqi women and girls. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(31): 2008; 93–102.

- Human Rights Watch. Lebanon: residency rules put Syrians at risk. https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/12/lebanon-residency-rules-put-syrians-risk. 2016 January 12

- Amnesty International. Lebanon: refugee women from Syria face heightened risk of exploitation and sexual harassment. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/02/lebanon-refugee-women-from-syria-face-heightened-risk-of-exploitation-and-sexual-harassment/. 2016 February 02

- B. Chit, M.A. Nayel. Understanding racism against Syrian refugees in Lebanon. 2013; Civil Society Knowledge Center, Lebanon Support. http://cskc.daleel-madani.org/paper/understanding-racism-against-syrian-refugees-lebanon.

- E. Swingewood. Syrian refugee women in Lebanon: gendering violence through Johan Galtung. E-International Relations Students. http://www.e-ir.info/2014/11/10/syrian-refugee-women-in-lebanon-gendering-violence-through-johan-galtung/. 2014 November 10

- R. Fowler. Syrian refugee families’ awareness of the health risks of child marriage and what organizations offer or plan in order to raise awareness. ISP Collection. http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2948&context=isp_collection. 2014

- United Nations Population Fund. From childhood to womanhood: meeting the sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescent girls. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/EN-SRH%20fact%20sheet-Adolescent.pdf. 2012

- A. Kaddour, H. Alameh, K. Melekian. Abortion In Lebanon: Practice and Legality?. Al-Raida. 99: 2002; 55–58.