Abstract

Populations around the world are rapidly ageing and effective treatment for HIV means women living with HIV (WLHIV) can live longer, healthier lives. HIV testing and screening programmes and safer sex initiatives often exclude older sexually active WLHIV. Systematically reviewing the literature to inform World Health Organization guidelines on the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of WLHIV, identified four studies examining healthy sexuality among older WLHIV. In Uganda, WLHIV reported lower rates of sexual activity and rated sex as less important than men. In the United States, HIV stigma, disclosure, and body image concerns, among other issues, were described as inhibiting relationship formation and safer sexual practices. Sexual activity declined similarly over time for all women, including for WLHIV who reported more protected sex, while a significant minority of WLHIV reported unprotected sex. A single intervention, the “ROADMAP” intervention, demonstrated significant increases in HIV knowledge and decreases in HIV stigma and high risk sexual behaviour. WLHIV face ageist discrimination and other barriers to remaining sexually active and maintaining healthy sexual relationships, including challenges procuring condoms and seeking advice on safe sex practices, reduced ability to negotiate safer sex, physical and social changes associated with menopause, and sexual health challenges due to disability and comorbidities. Normative guidance does not adequately address the SRHR of older WLHIV, and while this systematic review highlights the paucity of data, it also calls for additional research and attention to this important area.

Résumé

Partout dans le monde, la population vieillit rapidement et un traitement efficace du VIH signifie que les femmes séropositives peuvent vivre plus longtemps et en meilleure santé. Les programmes de dépistage du VIH et les initiatives pour des relations sexuelles plus sûres excluent souvent les femmes séropositives âgées sexuellement actives. Une analyse systématique des publications pour étayer les directives de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé sur la santé et les droits sexuels et génésiques des femmes séropositives a permis d’identifier quatre études portant sur une sexualité saine de femmes âgées vivant avec le VIH. En Ouganda, ces femmes ont signalé des taux inférieurs d’activité sexuelle ; les rapports sexuels étaient moins importants pour elles que pour les hommes. Aux États-Unis, la stigmatisation liée au VIH, la révélation de l’infection et les préoccupations autour de l’image corporelle ont notamment été décrites comme des facteurs empêchant de nouer des relations et de pratiquer une sexualité sans risques. L’activité sexuelle déclinait au fil du temps de manière similaire pour toutes les femmes, y compris celles qui vivent avec le VIH qui ont indiqué davantage de relations protégées, avec une minorité significative de femmes séropositives affirmant qu’elles avaient des rapports sexuels non protégés. Une seule intervention autour de la santé sexuelle pour les femmes âgées séropositives, le projet ROADMAP, a sensiblement augmenté la connaissance du VIH et diminué la stigmatisation due au VIH et les comportements sexuels à haut risque. Les femmes vivant avec le VIH se heurtent à une discrimination liée à l’âge, des obstacles pour demeurer sexuellement actives et conserver des relations sexuelles saines, notamment des difficultés pour se procurer des préservatifs et obtenir des conseils sur les pratiques sexuelles sûres. Elles sont moins à même de négocier des rapports sexuels sans risque et connaissent des changements physiques et sociaux associés avec la ménopause et des risques de santé sexuelle dus à l’invalidité et aux comorbidités. Les conseils normatifs n’abordent pas correctement la santé et les droits sexuels et génésiques des femmes âgées séropositives, et si cette analyse systématique met en lumière la pénurie de données, elle montre aussi qu’il est nécessaire de poursuivre les recherches et de se pencher sur ce domaine important.

Resumen

Las poblaciones del mundo están envejeciendo rápidamente y el tratamiento eficaz del VIH significa que las mujeres que viven con VIH (MVV) pueden vivir una vida más larga y más saludable. Los programas de pruebas y tamizaje de VIH e iniciativas de sexo más seguro a menudo excluyen a las MVV de edad más avanzada que son sexualmente activas. La revisión sistemática de la literatura para informar las guías de la Organización Mundial de la Salud sobre la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos (SSR y DD. SS. RR.) de las MVV, identificó cuatro estudios que examinaron la sexualidad saludable entre MVV mayores. En Uganda, las MVV informaron menores tasas de actividad sexual y calificaron el sexo como menos importante que los hombres. En Estados Unidos, el estigma relacionado con el VIH, la divulgación e inquietudes relacionadas con la imagen corporal, entre otros asuntos, fueron descritos como que inhiben la formación de relaciones y las prácticas sexuales más seguras. Asimismo, la actividad sexual disminuyó a lo largo del tiempo para todas las mujeres, incluidas las MVV que informaron tener sexo más protegido, mientras que una minoría significativa de MVV informó tener sexo sin protección. Una sola intervención en salud sexual para MVV mayores, la intervención "ROADMAP", demostró aumentos significativos en el conocimiento del VIH y disminución del estigma en torno al VIH y el comportamiento sexual de alto riesgo. Las MVV enfrentan discriminación por edad, barreras para continuar siendo sexualmente activas y mantener relaciones sexuales saludables, que incluyen retos para adquirir condones y buscar consejos sobre las prácticas de sexo seguro, menor capacidad para negociar sexo más seguro, cambios físicos y sociales asociados con la menopausia y retos de salud sexual debido a la discapacidad y comorbilidades. La orientación normativa no aborda adecuadamente la SSR y DD. SS. RR. de las MVV mayores. Mientras que esta revisión sistemática destaca la escasez de datos, también insta a que se realicen más investigaciones y a que se preste atención a esta área tan importante.

Introduction

Women of all ages, including women living with HIV, have a right to sexual health, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a state of physical, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality.Citation 1 This requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination, violence, and disease. [1] For the first time since the start of the HIV epidemic, 10% of the adult population living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries, and 30% in high-income countries, are aged 50 or older, accounting for an estimated 3.6 million people globally.Citation 2 The distribution of people living with HIV aged 50 and older is not even, but varies across locations; for example, in the US states of Florida and New York, 45% and 50% respectively of people living with HIV are aged 50 and older.Citation 3,4 Moreover, globally, the demographics point to growing numbers of older populations, including older people living with HIV, due in part to access to antiretroviral treatment and care.Citation 5

These trends present several challenges. Higher mortality rates in people aged 50 years and older may pose special challenges for antiretroviral drug initiation or continuation in this age group.Citation 6 Immune function declines across the life course, increasing vulnerability to other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and some clinicians suggest that older age may be an indication for more aggressive treatment.Citation 7 Post-menopausal changes to the vagina can reduce innate protective mechanisms against infection. Older women living with HIV along with another chronic or infectious disease have increased vulnerability to additional infectious diseases.Citation 8

People aged 50 years and older exhibit many of the risk behaviours found among younger people. Older adults have been found to have less knowledge regarding the risk of HIV compared to younger populationsCitation 9–11 and are less likely to wear condoms.Citation 12–14 In the US, older women, including the baby boomer generation, may be more open to sex and sexuality in general compared with previous generations.Citation 15 In addition, postmenopausal women do not need to worry about unplanned pregnancy.Citation 16,17 Older women may perceive years of sex with HIV-negative partners as evidence of low risk of transmission. Finally, older women may have more difficulty discussing condom use with sexual partners for the use of HIV prevention.Citation 14 Yet, in many low- and middle-income countries, testing and screening programmes for HIV routinely exclude older people, and safer sex initiatives generally target younger age groups.

Older women living with HIV experience a range of other social challenges. As women tend to live longer than men, a significant proportion of older women are either widowed or single. Around the world, women living with HIV report feeling rejected, depressed, and socially excluded,Citation 18 and women living with HIV are at increased risk of depression.Citation 19 Older women living with HIV in Africa may have to survive with little support from family or carry the burden of caring for children.Citation 20,21 Moreover, older women living with HIV are more likely to experience depression compared to men living with HIV.Citation 22 While both loneliness and HIV stigma have been found to separately increase risk for depression, loneliness has been observed to have a much larger effect.Citation 23 Social isolation, defined as living without support or social connection,Citation 24 also directly effects health through mechanisms such as increasing cardiovascular risk,Citation 25 particularly in women, compounding the burden of living with HIV.Citation 26

Widespread ageist stereotypes may also make it embarrassing or difficult for older women, including older women living with HIV, to procure condoms or to seek advice on safe sex practices.Citation 27–29 Ageism – the pervasive discrimination against individuals or groups based on ageCitation 2 – can be a barrier to creating inclusive policies and obtaining quality social and healthcare for older populations. Some point to ageism as responsible for the lack of HIV-related messages aimed at older women.Citation 13 In addition, ageism can lead to reduced self-efficacy in older individuals.Citation 30 Older women may also confront lowered ability to negotiate safe sex as they are beyond reproductive years and the fear of pregnancy is no longer present.Citation 31 Older women living with HIV, particularly those living in low resource settings, may also face additional vulnerabilities to their sexual health and wellbeing, such as lack of property rights and the necessity to care for orphaned grandchildren.Citation 20

To date, research examining sexual relationships, HIV and ageing in older adults has primarily focused on HIV prevention in HIV-negative populations, although even this literature is limited.Citation 32 Women living with HIV encounter different sets of challenges and harbor different desires, visions, and priorities during the later stages of their lives that are not captured in the current HIV literature. While there is an understandable initial focus on pregnancy for those who desire it and prevention of vertical transmission of HIV, this is a one-dimensional approach which risks overwhelming other, equally important, SRHR issues that can enhance women’s agency, choice, empowerment, and fulfilment of their sexual health goals.Citation 33

What is the evidence on ageing and healthy sexuality for women living with HIV?

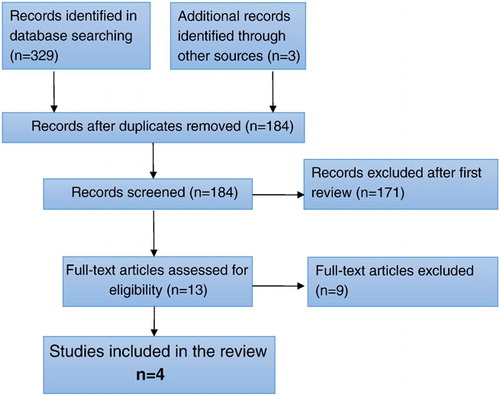

To inform WHO guidelines for SRHR for women living with HIV, we systematically reviewed the literature on ageing and healthy sexuality among women living with HIV. We sought to describe the existing evidence base in terms of types of studies, populations, and research questions, and identify key findings which can be used to inform programs and policies for this population. We followed PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews.Citation 34 Articles were included if they presented either qualitative or quantitative primary data collected among women living with HIV, described the relationship between ageing and sexual behaviours or experiences of intimacy, and were published in a peer-reviewed journal through February 18, 2016. Articles presenting data for both men and women living with HIV were included if they stratified results by gender and presented at least some data separately for women. We searched PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts using a set of search terms on HIV, women, ageing, and sexuality adapted for each database (available upon request). We screened abstracts for initial consideration, reviewed selected full-text articles in duplicate to finalize study selection, and extracted data in duplicate using systematic forms.

Of 184 unique abstracts identified in the search, 13 articles were pulled for full-text review and just four articles ultimately met the criteria for inclusion in the review ( ). Three studies were conducted in the United States and the fourth was conducted in Uganda. presents descriptions of the included studies. Major themes from these articles are described below and include barriers to maintaining healthy sexuality and the impact of HIV stigma on developing relationships and sexual practices.

Table 1 Descriptions of included studies

A study in Uganda investigated sexual behaviour in men (n = 42) and women (n = 59) living with HIV over the age of 50 and found a sharp difference in sexual activity based on gender.Citation 35 Only 14% of women reported being sexually active compared to 49% of men, and only 5% of women rated sex as being extremely or very important compared to 41% of men (OR = 0.11, p < 0.01). A multivariate logistic regression found that female gender was associated with an 80% reduction in the odds of being sexually active in the past year (OR = 0.19, p < 0.05). No woman over the age of 60 reported being sexually active, though men over the age of 60 reported similar sexual activity compared to men in their 50s. Despite the large difference in sexual activity between men and women in this study, both women and men reported their level of interest in sex and their own HIV status as factors which most limited their sexual activity. For both men and women, better physical function was shown to increase the odds of sexual activity in the past 12 months (OR = 1.84, p < 0.01). The authors suggest that lack of sexual activity in the female sample may correspond to subsequent perceptions of diminished importance of sex. The authors also noted that rates of sexual activity in this population were lower than rates of sexual activity in studies of HIV-negative populations in comparable settings.

In the Boston area of the United States, a qualitative study conducted with 19 women over the age of 50 (mean age = 56.79) living with HIV investigated the way older women living with HIV think about intimate partner relationships.Citation 36 Three main themes emerged from interviews: 1) the negative impact of HIV stigma on intimate partner relationships, 2) body image concerns as a barrier to intimate partner relationships, and 3) the dilemma of HIV disclosure. Most participants (16 of 19) reported not having a current partner but still desiring one. Stigma in the form of a potential partner’s preconceived notions of HIV was the most cogent barrier to developing intimate partner relationships. This stigma included assumptions that women living with HIV have engaged in sex work or drug use, that HIV is difficult to manage, and that HIV will result in financial burdens. In addition, many participants feared the power differential in a serodiscordant relationship. Finally, participants discussed experiencing body dissatisfaction, attributing it to the combination of long-term use of antiretroviral medications and menopause. Participants believed these bodily changes made them sexually undesirable to a partner. Although participants expressed a strong sense of obligation to disclose their HIV status to a potential partner, they also feared the partner’s reaction. In sum, women in this study reported feeling overwhelmed and hopeless in finding a partner, and many chose to abstain from sexual relationships instead of dealing with the possible repercussions of HIV disclosure.

The second study from the United States was a longitudinal study exploring the association between ageing, menopause, and sexual behaviour among women with and without HIV.Citation 37 Data came from six urban areas in the United States from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) cohort, which followed 3,847 participants for over 13 years. Data were presented for three groups: 1) women without HIV, 2) women living with HIV with undetectable viral load, and 3) women living with HIV with detectable viral load. The study found that for every 10-year increase in age, the odds of any sexual activity declined by 62% for women with HIV and detectable viral load (OR = 0.38 [0.34-0.41]), by 64% in women with HIV and undetectable viral load (OR = 0.36 [0.33-0.40]), and by 62% for HIV-negative women (OR = 0.38 [0.33-0.44]). Differences among virologic groupings in any sexual activity for every 10-year increase in age were non-statistically significant (p = 0.693). The odds of unprotected sex decreased over time, and women living with HIV maintained a pattern of reporting less unprotected sex than women without HIV. The odds of unprotected sex declined by 17% for every 10-year increase in age for women living with HIV with detectable viral load (OR = 0.83 [0.74-0.92]), a statistically significant (p = 0.036) decline in odds of unprotected sex in relation to HIV-positive women with undetectable viral load (OR = 0.91 [0.81-1.01]) and HIV-negative women (OR = 0.96 [0.83-1.01]). However, after 13 years of follow-up the study found 22–25% of HIV-positive women continued to engage in unprotected sex. The study found that older women living with HIV experience a “menopause effect” in which odds of any sexual activity decreases after menopause (OR = 0.78 [0.68-0.90] for HIV-positive women with detectable viral load, OR = 0.75 [0.64-0.87] for HIV-positive women with undetectable viral load).

The final study from the United States evaluated a sexual risk reduction intervention for older women living with HIV.Citation 38 Echenique et al conducted an evaluation of Project ROADMAP, a 6-month intervention designed to reduce sexual risk behaviour among a population of women over 45 years of age) living with HIV in the Miami, Florida area. Women in the study (n = 106) were primarily African-American, heterosexual, recently sexually active, and attained high school education or less. Participants were randomly assigned to intervention and control groups. The intervention consisted of four weekly psycho-educational group sessions tailored for older adults living with HIV. Group sessions covered HIV education, harm reduction and safer sex practices, and skill-building for assertive partner communication and condom negotiation. The control group received brochures and standard care. Inconsistent condom use with all partners, regardless of the partner’s HIV status, was different among women in the control group (12.2%) and intervention group (20%) at baseline. The study presented change in outcomes over time for each study group, but did not provide comparison of pre and post data between the two study groups. For both groups, inconsistent condom use dropped at six-month follow-up (9.8% and 9.2%, respectively) but the difference was only statistically significant for the intervention group (p < 0.05). The study also measured a significant increase in the knowledge index score from baseline to six-month follow-up in the intervention group (26.6 to 28.7, p < 0.01) and a decrease in the mean stigma score (104.6 to 96.5, p < 0.05). The researchers concluded that group-based interventions may be especially important for engaging older women living with HIV because they provide social and emotional support for healthy sexual decision-making and reduce stigma. The authors noted that no similar group support was available for older women in the study community, thus making the effect of the group sessions especially powerful.

While this very limited evidence base is reflective of a broader gap in the literature around sexual health and rights among people older than 50 years,Citation 39 it is still disappointing given the increased attention to ageing and HIV more generally. The four studies were diverse, including both qualitative and quantitative studies and one intervention evaluation, but only one study was from sub-Saharan Africa which has the greatest burden of HIV. Findings suggest that women living with HIV face significant barriers to maintaining healthy sexuality as they age. One of the main barriers is HIV stigma, which impacts older women living with HIV and can influence the perceived ability to initiate and maintain intimate relationships, sexual functioning, sexual practices, and self-image. While sexual activity declines with age for all women, including women living with HIV, further research is needed on how much of this decline is by choice. Finally, there is initial evidence that sexual health interventions with older women living with HIV can be feasible and effective.

Where do we go from here?

Greater attention from the public health community is required to meet the sexual health needs and rights of older women living with HIV.Citation 40 Sexuality across the life course involves numerous physical and social transitions. For all women, including women living with HIV, menopause marks a period of significant physiologic change. Depending on the setting, this may be accompanied by a shift in social role and self-image. Access to health education during this period is crucial if women are to adjust and their sexual expression is to evolve. This will require a better understanding of sexuality in older age among health professionals, and enhanced support for women living with HIV to openly discuss sexuality. Women living with HIV are particularly subjected to stigma, discrimination and negative attitudes related to their behaviour by their families, communities, and health workers.Citation 18,29,41

Health care providers often perceive older women to be at lower risk for STIs, including HIV.Citation 31 Healthcare practitioners often avoid discussing HIV with older women, including not ordering HIV tests, because of the expectation of sexual inactivity in older women or the misconception that HIV is irrelevant to older patients.Citation 42,43 In Uganda, older women, including those living with HIV, were uncomfortable using available HIV services because of the stigma of being recognized in the community and the discomfort of discussing sensitive questions about sexuality with younger health care providers.Citation 44 The failure to address sexual health in older women may be due to the conflation of female sexuality with reproduction.Citation 43 Subsequently, the sexual well-being of women beyond childbearing age is ignored. The absence of training for healthcare workers on the specific health issues and support strategies for older women living with HIV further contributes to their marginalization. It leaves healthcare providers ill-equipped to address sexual health needs and rights and perpetuates discriminatory practices, even to the point of refusing services. Efforts and resources must be leveraged so that healthcare providers working with older women living with HIV remain non-judgmental, supportive, responsive, and respectful.

The discourse around sexual risk behaviours and HIV is rapidly changing due to expanding access to highly effective treatment and the proven reduction in HIV transmission risk associated with viral suppression. Evidence suggests that people living with HIV over 50 may be more likely to adhere to antiretroviral therapy (ART), but multiple comorbidities common among older adults can make clinical management and ART use challenging.Citation 45,46 Nevertheless, older women living with HIV, their clinicians, and public health practitioners should consider the reduced risk of HIV transmission associated with viral suppression in discussions around the riskiness of sexual behaviour. Comorbidities and disability also impact sexual functioning among older women and should be addressed in strategies to help them achieve healthy sexual lives.Citation 17

In conclusion, women living with HIV face ageist discrimination and significant barriers to maintaining healthy sexual relationships as they age. At this time, key normative guidance does not adequately address the needs of older women living with HIV. Our systematic review yielded few articles, which highlights the need for additional research and attention in this area, particularly as global population demographics and the epidemiology of HIV change.

References

- World Health Organization. Sexual health, human rights and the law. Report No. 9241564989. 2015; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland. 49 pp. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/sexual-health-human-rights-law/en/

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. 2015; WHO: Luxembourg 260 pp. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/186463/1/9789240694811_eng.pdf

- Bureau of HIV/AIDS Epidemiology, AIDS Institute, New York State Department of Health. New York State HIV/AIDS Surveillance Annual Report 2013. 2015; BHAE and NYSDOH: Albany, NY, 120 pp. Available from: http://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/general/statistics/annual/2013/2013-12_annual_surveillance:report.pdf

- Florida Department of Health Division of Disease Control and Protection. Florida Monthly Surveillance Report for Hepatitis, HIV/AIDS, STD, and TB: January 2014. 2014; Florida Department of Health: Tallahassee, FL 18 pp. Available from: http://www.floridahealth.gov/%5C/diseases-and-conditions/aids/surveillance/_documents/msr/2014-msr/MSR0214.pdf

- M. Lusti-Narasimhan, J.R. Beard. Sexual health in older women. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 91(9): 2013; 707–709.

- Central Statistics Office. Ageing in Ireland. 2007; Center for Ageing Research and Development in Ireland: Dublin, Ireland 43 pp. Available from: http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/otherreleases/2007/ageinginireland.pdf

- O. Drew, J. Sherrard. Sexually transmitted infections in the older woman. Menopause International. 14(3): 2008; 134–135.

- S.K. Plach, P.E. Stevens, S. Keigher. Self-care of women growing older with HIV and/or AIDS. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 27(5): 2005; 534–558.

- S.J. Henderson, L.B. Bernstein, D.M.S. George, et al. Older women and HIV: How much do they know and where are they getting their information?. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 52(9): 2004; 1549–1553.

- S.P. Weaver, C. Passmore. Older adults’ knowledge concerning risk factors for HIV transmission. Texas Academy of Family Physicians. 9: 2012; 1.

- J. Negin, B. Nemser, R. Cumming, et al. HIV attitudes, awareness and testing among older adults in Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 16(1): 2012; 63–68.

- N. Nguyen, M. Holodniy. HIV infection in the elderly. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2008: 2008; 453.

- M.M. Neundorfer, P.B. Harris, P.J. Britton, et al. HIV-risk factors for midlife and older women. The Gerontologist. 45(5): 2005; 617–625.

- D. Zablotsky, M. Kennedy. Risk factors and HIV transmission to midlife and older women: knowledge, options, and the initiation of safer sexual practices. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 33: 2003; S122–S130.

- R.J. Jacobs, M.N. Kane. HIV-related stigma in midlife and older women. Social Work in Health Care. 49(1): 2010; 68–89.

- S.T. Lindau, S.A. Leitsch, K.L. Lundberg, et al. Older women's attitudes, behavior, and communication about sex and HIV: a community-based study. Journal of Women's Health. 15(6): 2006; 747–753.

- T.N. Taylor, C.E. Munoz-Plaza, L. Goparaju, et al. "The Pleasure Is Better as I've Gotten Older": Sexual Health, Sexuality, and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Older Women Living With HIV. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016; (epub ahead of print)

- L. Orza, S. Bewley, C.H. Logie, et al. How does living with HIV impact on women's mental health? Voices from a global survey. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 18(Suppl 5): 2015; 20289.

- M.F. Morrison, J.M. Petitto, T.T. Have, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159(5): 2002; 789–796.

- A.O. Wilson, D.J. Adamchak. The grandmothers' disease and the impact of AIDS on Africa's older women. Age and Ageing. 30(1): 2001; 8–10.

- F. Scholten, J. Mugisha, J. Seeley, et al. Health and functional status among older people with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 11(1): 2011; 1.

- Medical Research Council, Uganda Virus Research Institute. Direct and indirect effects of HIV/AIDS and anti-retroviral treatment on the health and wellbeing of older people [WHO’s Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE)]. 2011; Uganda Virus Research Institute and Medical Research Council: Kampala, Uganda

- C. Grov, S.A. Golub, J.T. Parsons, et al. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 22(5): 2010; 630–639.

- G. Hawthorne. Measuring social isolation in older adults: development and initial validation of the friendship scale. Social Indicators Research. 77(3): 2006; 521–548.

- N. Grant, M. Hamer, A. Steptoe. Social isolation and stress-related cardiovascular, lipid, and cortisol responses. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 37(1): 2009; 29–37.

- R.A. Hackett, M. Hamer, R. Endrighi, et al. Loneliness and stress-related inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses in older men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 37(11): 2012; 1801–1809.

- N.J. Sabik. Ageism and Body Esteem: Associations With Psychological Well-Being Among Late Middle-Aged African American and European American Women. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 70(2): 2015; 189–199.

- J.C. Chrisler, A. Barney, B. Palatino. Ageism can be Hazardous to Women's Health: Ageism, Sexism, and Stereotypes of Older Women in the Healthcare System. Journal of Social Issues. 72(1): 2016; 86–104.

- C.A. Emlet. “You're Awfully Old to Have This Disease”: Experiences of Stigma and Ageism in Adults 50 Years and Older Living With HIV/AIDS. The Gerontologist. 46(6): 2006; 781–790.

- B. Levy, O. Ashman, I. Dror. To be or not to be: The effects of aging stereotypes on the will to live. Omega. 40(3): 2000; 409–420.

- J. Altschuler, S. Rhee. Relationship Power, Sexual Decision Making, and HIV Risk Among Midlife and Older Women. Journal of Women & Aging. 27(4): 2015; 290–308.

- A. Sankar, A. Nevedal, S. Neufeld, et al. What do we know about older adults and HIV? A review of social and behavioral literature. AIDS Care. 23(10): 2011; 1187–1207.

- Salamander Trust. Building a safe house on firm ground: key findings from a global values and preferences survey regarding the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of women living with HIV. 2014; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland

- D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 6(7): 2009; e1000097

- J. Negin, L. Geddes, M. Brennan-Ing, et al. Sexual Behavior of Older Adults Living with HIV in Uganda. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 45(2): 2016; 441–449.

- C. Psaros, J. Barinas, G.K. Robbins, et al. Intimacy and sexual decision making: Exploring the perspective of HIV positive women over 50. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 26(12): 2012; 755–760.

- T.N. Taylor, J. Weedon, E.T. Golub, et al. Longitudinal trends in sexual behaviors with advancing age and menopause among women with and without HIV-1 infection. AIDS and Behavior. 19(5): 2015; 931–940.

- M. Echenique, L. Illa, G. Saint-Jean, et al. Impact of a secondary prevention intervention among HIV-positive older women. AIDS Care. 25(4): 2013; 443–446.

- I. Aboderin. Sexual and reproductive health and rights of older men and women: addressing a policy blind spot. Reproductive Health Matters. 22(44): 2014; 185–190.

- C. Psaros, J. Barinas, G.K. Robbins, et al. Reflections on living with HIV over time: exploring the perspective of HIV-infected women over 50. Aging & Mental Health. 19(2): 2015; 121–128.

- I. Familiar, S. Murray, H. Ruisenor-Escudero, et al. Socio-demographic correlates of depression and anxiety among female caregivers living with HIV in rural Uganda. AIDS Care. 1-5: 2016.

- D.M. Conde, E.T. Silva, W.N. Amaral, et al. HIV, reproductive aging, and health implications in women: a literature review. Menopause. 16(1): 2009; 199–213.

- B. Cooper, C. Crockett. Gender-based violence and HIV across the life course: adopting a sexual rights framework to include older women. Reproductive Health Matters. 23(46): 2015; 56–61.

- E. Richards, F. Zalwango, J. Seeley, et al. Neglected older women and men: Exploring age and gender as structural drivers of HIV among people aged over 60 in Uganda. African Journal of AIDS Research. 12(2): 2013; 71–78.

- M.J.L.W. Silverberg, M.A. Horberg, G.N. DeLorenze, D. Klein, C.P. Quesenberry Jr.. Older age and the response to and tolerability of antiretroviral therapy. Archives of Internal Medicine. 167(7): 2007; 684–691.

- J.G.M. Scott. Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome in Older Adults. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 32(3): 2016; 571–583.