Abstract

In October 2012, a new law was approved in Uruguay that allows abortion on demand during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, 14 weeks in the case of rape, and without a time limit when the woman's health is at risk or in the case of foetal anomalies. This paper analyses this legal reform. It is based on 27 individual and group interviews with key informants, and on review of primary documents and the literature. The factors explaining the reform include: secular values in society, favourable public opinion, a persistent feminist movement, effective coalition building, particular party politics, and a vocal public health sector. The content of the new law reflects the tensions between a feminist perspective of women's rights and public health arguments that stop short of fully recognizing women's autonomy. The Uruguayan reform shows that, even in Latin America, abortion can be addressed politically without electoral cost to the parties that promote it. On the other hand, the prevailing public health rationale and conditionalities built into the law during the negotiation process resulted in a law that cannot be interpreted as a full recognition of women's rights, but rather as a modified protectionist approach that circumscribes women's autonomy.

Résumé

En octobre 2012, une nouvelle loi a été approuvée en Uruguay qui autorise l’avortement à la demande pendant les 12 premières semaines de grossesse, 14 semaines en cas de viol, et sans limite de temps si la santé de la femme est à risque ou en présence d’anomalies fœtales. L’article analyse cette réforme juridique. Il est fondé sur 27 entretiens individuels et en groupe avec des informateurs clés et sur l’analyse de documents primaires et de publications. Les facteurs expliquant la réforme incluent: les valeurs laïques de la société, l’opinion publique favorable, un mouvement féministe persistant, la création efficace de coalitions, les politiques de partis particuliers et un secteur de la santé publique qui fait entendre sa voix. Le contenu de la nouvelle loi reflète les tensions entre une perspective féministe des droits des femmes et des arguments de santé publique qui ne reconnaissent pas pleinement l’autonomie des femmes. La réforme uruguayenne montre que, même en Amérique latine, l’avortement peut être abordé politiquement sans coût électoral pour les partis qui le défendent. D’autre part, les justifications et conditions prédominantes de santé publique incluses dans la loi pendant le processus de négociation ont abouti à ce que la loi soit interprétée non comme une pleine reconnaissance des droits des femmes, mais plutôt comme une approche protectionniste modifiée qui circonscrit l’autonomie des femmes.

Resumen

En octubre de 2012, una nueva ley fue aprobada en Uruguay que permite el aborto a petición durante las primeras 12 semanas del embarazo, 14 semanas en casos de violación y sin límite de tiempo cuando la salud de la mujer está en peligro o en casos de anomalías fetales. Este artículo analiza esta reforma legislativa. Se basa en 27 entrevistas individuales y en grupo con informantes clave, así como en la revisión de documentos principales y la literatura. Entre los factores que explican la reforma figuran: valores seculares en la sociedad, opinión pública favorable, un movimiento feminista persistente, la creación de coaliciones eficaces, política de partidos específicos y un sector salud pública vocal. El contenido de la nueva ley refleja las tensiones entre una perspectiva feminista de los derechos de las mujeres y argumentos de salud pública que no reconocen plenamente la autonomía de las mujeres. La reforma uruguaya muestra que, incluso en Latinoamérica, el tema del aborto puede ser abordado políticamente sin costo electoral para los partidos que lo promueven. Por otro lado, la justificativa predominante de salud pública y las condicionalidades incorporadas en la ley durante el proceso de negociación produjeron una ley que no puede ser interpretada como reconocimiento total de los derechos de las mujeres, sino como un enfoque proteccionista modificado que circunscribe la autonomía de las mujeres.

Introduction

On October 22, 2012, President José Mujica signed into law the “Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy” bill, making Uruguay the first country in South America to recognize the right to abortion on broad grounds. This change was the fruit of more than two decades of advocacy, led by feminist organizations in alliance with trade unions, student groups and other actors, including the medical sector and key political leaders.

Abortion reform in Uruguay has been the focus of several excellent studies.Citation 1,2 This article, based on a descriptive study of the context and political processes for abortion reform,Citation 3 aims to identify the strategies and facilitating factors that led to the legal reform and the limitations of the law, as well as to view the process through a political and feminist lens that draws attention to the limitations of the outcome from a women’s rights perspective. In our interpretation this law has not meant a full recognition of women’s autonomy, but rather a shift in the terms of state protection of women’s health, which reflects the strong influence of a public health or biomedical viewpoint. Both the success of the legal reform and the persistence of state protection is understood through analysis of key actors’ discourses and interpretation of the social, cultural and political conditions of the Uruguayan context and of the legal reform process itself.

Methods

This study is based on 27 individual and group interviews with an intentional sample of key informants: legislators from different parties, party and union leaders, public health officials, health practitioners, feminists and other social activists and scholars, selected for diverse professional and political background and experience, differential positions in regard to abortion, and distinct roles in the process of the reform. Research questions explored descriptions of the process, as well as political interpretations of what happened. This paper focuses on the latter, in order to show the particularities and complexities of the Uruguayan context.

With the oral consent of the interviewees, interviews were taped, transcribed and analysed using manual qualitative research techniques (basic content analysis). In addition, the wording of the proposed and approved bills and related health regulations, public statements made by the judiciary and legislators, and secondary sources, including statistics, public opinion surveys and social sciences studies, were examined. This corpus was analysed in order to reconstruct the political process, understand the dynamics of the negotiations, and interrogate different interpretations of the final result.

Abortion law in Uruguay and factors that shaped change

Abortion had been criminalized under the Penal Code since 1898, except for a brief period between 1934 and 1938, when abortion was decriminalized due to public indignation over a woman’s death from an unsafe abortion.Citation 4 The 1938 law defined abortion as a crime, but the punishment could be mitigated in the case of rape, “family honour” (when the woman was an unmarried “virgin”, regardless of whether the pregnancy resulted from rape), undue economic burden, or danger to the woman's life. The procedure, performed by a doctor, was available up to three months of gestation, except in the case of danger to the life of the woman, in which case there was no limit.

Uruguay lived under military dictatorship from 1973 to 1985. Once democracy was restored, feminist organizations mobilized around abortion. During the following years, four bills to decriminalize abortion were initiated. The first of these, in 1985, failed to make it to the parliament, because it was not considered a priority in the context of the transition to democracy and was not in the platform of the ruling parties. In 2004, another bill was defeated in the Senate by only four votes. With each of these efforts, the issue of abortion gained increased visibility.

In 2005, the Frente Amplio (Broad Front, or “Front”), a centre-left coalition of parties, assumed the presidency for the first time. In 2008, the Parliament approved a comprehensive Sexual and Reproductive Health Bill, including articles decriminalizing abortion up to 12 weeks without restriction and without a gestational limit in the case of rape, severe health risk, or foetal anomalies. The Front President Tabaré Vázquez, a medical doctor, signed the bill except for the abortion articles, which he singled out to veto, despite his own party being in favour of them.

Passage of the law in 2012

Immediately following the 2008 veto, feminists and their allies, including political leaders within the Broad Front, mobilized to advocate for a new bill. In the 2009 elections, the Front elected José Mujica as president and retained a majority in parliament. A window of opportunity was opened for abortion to be addressed once again.

In Uruguay, both houses of parliament must approve a new law. In September 2012, the Senate passed an abortion bill, which included articles similar to those vetoed in 2008. Once the bill reached the House of Representatives, the Front realized that – despite their absolute majority – they did not have the votes necessary to approve the law due to opposition from just one member of the coalition. In the negotiations, Representative Iván Posada, from a small Christian Democratic Independent Party, offered the vote they needed. In exchange for his vote, however, Posada required the text to be modified. These alterations, which will be outlined below, voided the original emphasis on women’s rights and imposed numerous restrictions on access to abortion services.

The House passed the Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy Law on September 25, 2012, with 50 votes in favour and 49 against. On the 17th of October, the Senate ratified the bill, as modified by the House. President Mujica signed it five days later. Characteristics of the Uruguayan political and social context help explain the legal reform process and the resulting law.

Political culture and context

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Uruguayan political culture has been strongly secular, with a small, mostly urban, population and high levels of education. No religion has official status. For many years, two parties dominated Uruguayan politics.Citation 5 In 1971, the Broad Front, an alliance of Leftist parties, was born, but two years later, a military coup led to dictatorship. With the return of democracy in 1985, the two traditional parties again won alternate elections, until the Front victory in 2004. Since then, the Front has held the presidency and a majority in parliament. The leadership of the Front historically favoured legal abortion.

Vázquez went against his own party alliance in 2008 when he vetoed decriminalization. Only three government ministers signed the veto, an indication of conflict within the Front.Citation 6 Even his own party within the Front, the Socialists, repudiated the veto, leading Vázquez to quit the party, although he remained in the Front as an independent, and as such would be re-elected president in 2014.

The veto was criticized not only for the dismissal of women’s rights, but also because it was perceived as authoritarian, unusual in Uruguayan political culture that emphasizes consensus. And it created “a political debt” on the part of the Front to those in favour of decriminalization, which was to be settled when President Mujica took office in 2009.

These political debates were unfolding in an environment in which public opinion was largely in favor of decriminalization. In practice, criminalization of abortion had rarely been enforced,Citation 4 reflecting an attitude of acceptance. During the 1990s, public opinion polls showed that support for decriminalization hovered at about 60%.Citation 7 In 2002, two deaths due to unsafe abortion were registered and, in a country in which abortion-related maternal mortality had historically been low, a public debate erupted.Citation 8 In 2003, when the legislative process that led to the Sexual and Reproductive Health Act was launched, 63% of the population supported the decriminalization of abortion.Citation 9

Feminist persistence and alliance building

In the late 19th century, feminists and women workers organized within anarchist and socialist groups.Citation 9,10 The role women played in organized labour would be influential decades later, in the alliances supporting abortion reform.

During the 1960s and 1970s, many women were involved in left-wing parties and were active in resistance to the military dictatorship. With the return to democracy in the mid-1980s, feminists joined the broad-based coalition pressing for a transition to democracy. This coalition discussed the legalization of abortion, but did not include it in their platform, considering it secondary to the institutionalization of elections, discussions of transitional justice, and implementation of economic reforms.

In the 1990s, the feminist movement took on abortion as a priority issue and began to build a much wider coalition in support of legal change. The alliance between feminist organizations and trade unions led to abortion decriminalization becoming a rallying point for the labour movement. In 2001, the Central Workers Union adopted a resolution in favour of legal abortion at their national congress.Citation 3 Given the weight trade unions have within the Front and broader Uruguayan political culture, this step was crucial to the legitimization of abortion as a social justice issue.

Feminist organizations interacted successfully with local governments, students and academia as well. Starting in the early 1990s, the most prestigious university in Uruguay began producing and disseminating information on abortion and, in 2008, declared its institutional support for legal abortion.Citation 3

Feminists also worked with the medical sector and public health officials. For example, in response to maternal deaths due to unsafe abortion in 2001-2002, Mujer y Salud Uruguay (MYSU) worked with gynaecologists from the Hospital Pereira Rossell, the main maternal healthcare centre in the country, to improve services for women seeking information or post-abortion care.Citation 8,11

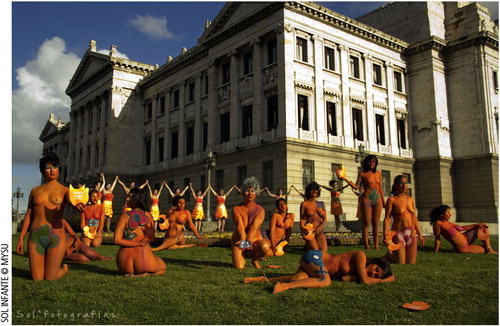

After the 2008 veto, feminists redoubled their efforts, working with legislators and keeping the issue visible. In 2009, an election year, MYSU coordinated a protest in which naked women with brightly painted bodies laid siege to the Parliament. They repeated this provocative “Naked Bodies” protest in September 2012, during the vote in parliament. In June 2013, they led a successful campaign “I won’t vote. Will you?” to encourage voters not to go to the polls for the pre-referendum that could have resulted in a referendum to overturn the law.Citation 10,12

Public health arguments and actors

In Uruguay, public health has been an instrument of state regulation of society, as exemplified by the control of sex work, which is recognized and regulated with public health measures that are unique in Latin America.Citation 13,14 This commitment to public health can be seen in Uruguay’s recent decision to buck the global trend toward privatization and move toward universal health care, with the state playing a major role in the funding, regulation and provision of care. A 2008 health reform established two linked systems: a public-private network and a public health system. Health regulations and financing apply to all medical procedures, including abortion, in both public sector and private institutions.

In the early 2000s, the medical sector began to play a more active role in calling for abortion reform. In 2002, public health professionals, such as Leonel Briozzo, later vice-Minister of Health, argued that women should be offered pre- and post-abortion counselling to avert death and injury from unsafe abortion,Citation 3,15,16 a strategy inspired by the harm reduction response to injecting drug use in the context of HIV.

In August 2004, just months after a bill to legalize abortion suffered a parliamentary defeat, the Ministry of Health adopted a protocol on harm reduction related to unsafe abortion. This approach was a recognition that, despite illegality, women interrupt pregnancies and that the public health sector must take measures to reduce related risks, which helped to mitigate the health consequences of illegal abortion and reduce stigma.

The content of the 2012 law reflects a similar perspective, seeing abortion as a procedure that should be authorized in certain cases and under medical surveillance, in order to avert harm, but falling short of fully recognizing women’s right to decide on reproductive matters. The review of the new law’s content below shows how it limits women’s autonomy, narrows the range of options available, and leaves abortion that occurs outside the conditions defined in the law as a criminal act.

Content of the law

The new law authorizes abortion on demand during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and 14 weeks in the case of rape; there is no gestational limit when the woman’s health is at risk or in the case of severe foetal anomalies. The procedure is available within the public health system, free of charge. Abortion continues to be criminalized if performed outside of the parameters established by the law.

As a result of the parliamentary negotiations, and in contrast with the articles vetoed in 2008, the 2012 law became more restrictive. It requires women to meet with a three person inter-disciplinary team (a gynaecologist, a social worker and a mental health professional), in order to receive information about alternatives and the so-called risks involved, and thereafter wait five days for reflection, before being allowed to proceed. It also dictates that only gynaecologists can carry out the procedure. Another noteworthy difference is that whereas, in the case of rape, the 2008 bill put no gestational limit, the 2012 law only allows abortion up to 14 weeks and requires the woman to have filed a judicial complaint. The notion of conscientious objection, which in the 2008 bill was only available to individual practitioners, is extended to health institutions as a whole. The law also requires that the woman be a resident in Uruguay for at least one year before she can seek an abortion, whereas in 2008 the residency requirement was 42 weeks.

The final text of the new law has toned down the emphasis on women’s rights and explicitly includes rhetoric on the value of life and motherhood, as in the introductory paragraph:

“The State guarantees the right to conscientious and responsible procreation, recognizes the social value of motherhood, protects human life, and promotes the full exercise of the sexual and reproductive rights of the entire population.”

Most importantly, the law does not decriminalize abortion: women who have an abortion not in compliance with the conditions of the law – for example, outside the health system or beyond the gestational limits – are vulnerable to prosecution. As a consequence, women continue to face the threat of jail and risks to their health. In fact, in 2015, three women were prosecuted, and two of these imprisoned, for the crime of abortion.Citation 17 After six months in jail, these women had to move to another town because of the stigma and discrimination they faced at home.

Reaction to the new law

As soon as the law was approved, feminist organizations, such as MYSU, began monitoring implementation and preparing to fight backlash.Citation 18 Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health rapidly developed regulations, aimed at mitigating some of the law’s restrictions and requirements. Issued in November 2012, Executive Decree 375/012 established definitions of confidentiality and informed consent. The decree also specified a standardized abortion procedure: medical abortion using a combination of misoprostol and mifepristone, which was quickly incorporated into the national list of essential drugs. The Ministry then made large purchases of it to facilitate service provision.

Anti-abortion forces also rapidly mobilized to repeal the law and proposed a referendum to overturn it. In Uruguay, a referendum is called only if more than 25% of the registered electorate votes in favour of it in a pre-referendum. Such a pre-referendum was scheduled for June 2013. Feminists mobilized to urge people not to vote. They won a resounding victory when a mere 8.8% of registered voters participated, halting in its tracks the effort to hold a referendum to repeal the law.

When the attempt to bring a referendum failed, the opposition turned to the courts. In 2013, a group of gynaecologists brought a case to the Administrative Court to widen the scope of conscientious objection. They won the case in August 2015, resulting in the annulment of parts of the Decree that had regulated the exercise of consciousness objection, thereby making it easier for doctors to refuse to provide services or to participate in any stage of the process, such as the initial consultation that is required by the law.Citation 19

Lessons learned

The story of legal change in Uruguay offers lessons that could be instructive in other settings, especially in terms of the political organizing, alliance-building, the ability to shift the terms of the debate, and the recognition of a window of political opportunity.

Keys to success

More than any other single factor, it was the skill, commitment and persistence of the feminist movement that was responsible for change in Uruguay. In the words of Juan Castillo, former head of the unions and in 2015 one of the top officers at the Ministry of Work:

“I want everyone to know that this was not for free and it wasn’t easy. Women who have this right today, organizations like MYSU, my colleagues from the Department of Gender, nobody gave them anything. They made a space and they won, they won it, and today they enjoy everyone’s respect.”

Feminists succeeded because they built support across sectors. They forged alliances, particularly with female, but also male, members of unions, political parties, student groups, scholars, community-based organizations, as well as with groups and networks in the rest of Latin America and globally.

One obstacle to abortion reform in many settings is the belief that public opinion is against decriminalizing abortion. In reality, public opinion is often more nuanced. Feminists in Uruguay made abortion an issue of public debate and showed that the prevalent assumption that the public opposed decriminalization was false and that the political elite was more conservative than broader society. They produced and utilized evidence, such as public opinion polls and health and social science research, to dispel myths and argue for legalization. Their strategic use of slogans and public actions at key moments helped to maintain visibility and momentum.

The sectors in favour of change were able to draw upon Uruguay’s secular past and position abortion as a matter of rights and health, not a matter of religion. They did not allow the opposition to set the terms of the debate, but rather were able to frame abortion as matter of social justice. They succeeded in upending the idea that abortions should “naturally” be illegal, showing that this prohibition creates a false sense of “normalcy” that in fact conceals a great gender injustice, because the harm resulting from clandestine and unsafe abortion is exclusively inflicted on women.

Another lesson is the importance of timing and of understanding the political moment. Those in favour of reform saw that the victory of Mujica in 2009 created a window of opportunity. As a candidate, Mujica had stated that he would not veto abortion reform. The prospect of Vázquez returning to power in 2014 meant that this window was narrow. It was this understanding that explains, in part, why legislators and even feminists accepted the restrictions imposed at the later stage of negotiations that ultimately determined the law’s content.

Uruguayan political culture, which emphasizes consensus, was rocked when the president of a party that had consistently supported reform vetoed the articles on abortion. Feminists utilized the resulting political debt to work with allies in parliament to pass a law. In democratic systems, where parties articulate and aggregate interests, working with them is essential, even while recognizing that parties often put reproductive rights on the back-burner. The 2012 law was possible because a) a leftist coalition in favour of legal change existed; b) this coalition held a parliamentary majority; and c) the executive branch approved of the change. The lining up of the three elements made the difference between the negative outcome of 2008 and the positive outcome of 2012.

Cautionary tales

Legal change does not always mean a full-fledged recognition of women’s rights. The Uruguayan process of reform was traversed by a tension between a feminist narrative of abortion as a matter of women’s rights, and a biomedical view of abortion as a public health issue. Despite these tensions, at the end of the day, the arguments raised by these two sectors – women’s rights and public health – created the critical mass of support necessary to change the law. The outcome, however, left intact a deep seated culture of state regulation of social practices related to gender, sexuality and health.

The requirement that a gynaecologist must be involved in the consultation and write the prescription for medical abortion sharply limits the number of professionals who are allowed to provide services. This limitation is aggravated by the broad interpretation of conscientious objection, extending it to various kinds of participation in service provision and also to institutions. Overall, some 30% of gynaecologists have objected to providing services, and in some provinces it is more than 80%.Citation 4 This suggests that the medical sector may be more conservative than the general population, but also reflects a lack of commitment to women’s health and rights. In fact, many of the objectors are motivated by reasons other than religious beliefs or personal ethics. For example, they avoid providing abortion because of the continuing stigma or because they cannot charge extra fees, as they can for some procedures, e.g. caesarean sections.Citation 4 The lesson in this case is that including conscientious objection in the law, if at all, should be highly regulated and done within very strict limits.Citation 20

The reliance on medical abortion, resulting from Ministry of Health regulation that strongly recommended this method, has its downsides, as providers often do not offer alternative methods, such as an aspiration abortion, which some women prefer. Furthermore, providers may be reluctant to conduct later term abortions that require a surgical intervention. This points to the need to offer a range of methods and to train health providers in them.

Another unintended consequence may be that as no fee is charged for an abortion service, this can be a disincentive to providers who see it as a less good use of their time, suggesting that other reform processes may want to include ways to build in economic incentives for providers without passing costs on to women.

Feminist advocates believe that these barriers cause many women to abort clandestinely, especially outside of Montevideo. In 2013, 7,171 women, and in 2014, 8,500 women had legal abortions, a 20% increase in one year.Citation 21 The most recent data available show that as of the end of September 2015, 6,986 women had had a legal abortion, again an increase.Citation 22 Nonetheless, prior to the passage of the law, the estimated number of illegal abortions was between 16,000 and 33,000 per year; thus a large proportion of women must still be having abortions outside the health system, leaving them subject to the same legal and health risks they faced before the law changed.Citation 4 Indeed, in February 2016, a woman of 21 years died due to an incomplete, unsafe second trimester abortion outside the health system.Citation 23

Conclusion

The 2012 law was undoubtedly a breakthrough. Abortion is now allowed by law in Uruguay and its practice is normalized within the health system. This fosters a cultural shift that advances the right of a woman to make decisions concerning her reproductive, family, and sexual life. That legal abortion has started to become the “new normal” can be seen in the current position of the president who had vetoed the articles decriminalizing abortion in 2008, Vázquez, who publicly stated that he would not try to reverse the law when he returned to the presidency in 2015, knowing that he would face party and popular backlash.

Further, the health sector is now obliged to provide abortion services to women at no cost, a huge gain for women’s rights and social justice. The fact that abortion is within the law and is provided by the state has taken abortion out of the shadows, reducing stigma. Women now have the option of a legal abortion, as long they comply with the requirements, thereby not having to seek clandestine services and suffer the anxiety and shame that comes with that.

Nonetheless, the law in Uruguay is not the law that feminists wanted. Abortion remains a crime in the Penal Code, and the circumstances under which it is allowed are cumbersome and potentially humiliating. The reality is that to get the law passed within a narrow political window of opportunity, its supporters had to allow the inclusion of restrictive conditions. The content and language of the law also made explicit the power of the biomedical perspective over women’s autonomy, mainly because the woman’s decision is not enough to access a legal abortion and the intervention of a gynaecologist is an essential condition for an abortion to be considered legitimate.

The Uruguayan experience illuminates some of the likely obstacles after a change in law. First, many women do not know yet that abortion is legal.Citation 4 Second, stigma persists, especially in small towns. Third, conscientious objection by gynaecologists and by institutions has created barriers to access. Fourth, efforts to lower barriers to accessing services – making them available in the public health service exclusively, free-of-charge, using medical abortion – may have created new, unanticipated barriers, such as disincentivizing professionals who might refuse to provide services because of the lack of economic benefit. Fifth, there is information about legal abortions, but there is little information about the number and conditions of abortions performed outside the parameters of the law, i.e., illegally. Finally, the opposition is not sitting still. Attacks on abortion began almost the moment the law was approved. The anti-rights forces utilize new strategies, which must be met with counter-strategies.

Activists demonstrating in favour of legalized abortion in front of the Uruguayan Congress in Montevideo, 2012.

Passing a law to legalize abortion is never the end, it is just the beginning. Uruguay has become a reference point in Latin America. It shows that change is possible. But feminists cannot rest, as they monitor implementation and fight for an interpretation of the current law that guarantees that health professionals respect the autonomy of women. In the words of a MYSU activist,

“We will take up the fight for a better law. We deserve it.”

Acknowledgements

This article is based on a 2015 study of the process of legal reform conducted by two of its authors, Sonia Correa and Mario Pecheny, funded by IWHC. A report on the full study was published in Spanish in October 2016 by MYSU.Citation 3

Notes

* In 1996, Mujer y Salud Uruguay (Women and Health Uruguay), a coalition of women’s organizations and academics, organized the First National Meeting on Women and Health, with abortion as a central focus. MYSU registered as a nongovernmental organization in 2005.

† The harm reduction approach argues that while drug use is illegal and even considered an “evil,” it cannot be eradicated, therefore a public health response must be established to reduce morbidity and mortality related to HIV transmission through drug injection.

References

- N. Johnson, C. Rocha, M. Schenck. La inserción del aborto en la agenda político-pública uruguaya 1985-2013. Un análisis desde el Movimiento Feminista. 2015; Cotidiano Mujer: Montevideo

- I. Pousadela. Social mobilization and political representation: The women’s movement’s struggle for legal abortion in Uruguay. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations [Internet]. 27(1): 2016 Feb; 125–145. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11266-015-9558-2

- S. Correa, M. Pecheny. Abortus interruptus: política y reforma legal del aborto en Uruguay. 2016; MYSU: Montevideo

- R. Sanseviero. Condena, tolerancia y negación. El aborto en Uruguay. 2003; Universidad para la Paz: Montevideo

- P. Valenzuela Gutiérrez. Estabilidad presidencial y democracia en Uruguay. Una mirada a tres momentos. Revista Divergencia [Internet]. 1(1): 2012 Apr; 55–72. Available from: http://www.revistadivergencia.cl/docs/ediciones/01/04_estabilidad_presidencial_y_democracia.pdf

- O. Bottinelli. La opinión pública en los últimos quince años, la relación entre sistema político y opinión pública. Época. 1(2): 2010; 13–30.

- O. Bottinelli, D. Buquet. El aborto en la opinión pública uruguaya. Época. 1(2): 2010; 1–42.

- L. Abracinskas, A. López Gómez. Mortalidad materna, aborto y salud en Uruguay, un escenario cambiante. 2004; MYSU: Montevideo

- L. Abracinskas, A. López Gómez. Aborto en Uruguay. Debate en Cámara de Diputados [Internet]. 2008; MYSU: Montevideo Available from: http://www.mysu.org.uy/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Descargue-aqui-cuaderno-debate-en-c%C3%A1mara-de-diputados.pdf

- N. Johnson, A. López Gómez, G. Sapriza, et al. (Des)penalización del aborto en Uruguay: prácticas, actores y discursos. 2003; Universidad de la República y Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica: Montevideo

- L. Briozzo, G. Vidiella, B. Vidarte, et al. El aborto provocado en condiciones de riesgo emergente sanitario en la mortalidad materna en Uruguay. Revista Médica del Uruguay [Internet]. 18(1): 2002 Mayo; 4–13. Available from: http://www.scielo.edu.uy/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1688-03902002000100002

- S. Rostagnol. Te doy, pero no tanto. Te saco, pero algo te dejo. La historia del aborto en Uruguay. En Luzinete Simões Minela Gláucia de Oliveira, Susana Bornéo Funck. Politicas e fronteiras. Desafios feministas. 2: 2014; Tubarao-SC: Copiart. [425-438]

- N. Trajtenberg, C. Musto. Prostitución y trabajo sexual en Uruguay. Documento de Trabajo/FCS-DS; 2011/87. 2011; UR. FCS-DS

- J. Barrán. Medicina y sociedad en el Uruguay del novecientos: El poder de curar. 1992; Ediciones de la Banda Oriental: Montevideo

- L. Briozzo. Aborto provocado: un problema humano. Perspectivas para su análisis – estrategias para su reducción. Revista Médica del Uruguay [Internet]. 19(3): 2003 Jul; 188–200. Available from: http://www.scielo.edu.uy/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1688-03902003000300002

- L. Briozzo. Iniciativas sanitarias contra el aborto provocado en condiciones de riesgo. 2007; Arena: Montevideo

- Maldonado: dos mujeres a prisión por aborto ilegal [Internet]. El País. Available from: http://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/maldonado-mujeres-prision-aborto-ilegal.html 2015 March 17.

- MYSU. Estado de situación de la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos en Uruguay. Asegurar y avanzar sobre lo logrado. Informe 2010-2014 del observatorio nacional en género y salud sexual y reproductiva en Uruguay. 2015; MYSU: Montevideo Available from: http://www.mysu.org.uy/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/resumen-observatorio.pdf

- A. Faúndes, G.A. Duarte, M.H. de Sousa, et al. Brazilians have different views on when abortion should be legal, but most do not agree with imprisoning women for abortion. Reproductive Health Matters. 21(42): 2013; 165–173.

- D. Diniz, A. Madeiro, C. Rosas. Conscientious objection, barriers, and abortion in the case of rape: a study among physicians in Brazil. Reproductive Health Matters. 22(43): 2014; 141–148.

- Ministry of Health, Uruguay. Interrupción voluntaria de embarazo [Internet]. Available from: http://www.msp.gub.uy/noticia/interrupción-voluntaria-de-embarazo 2015 March 28.

- C. Tapia. Cada vez más abortos; se realizan 26 por día. El País. Available from: http://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/crece-cantidad-aborto-realizan-uruguay.html 2016 March 6.

- Una muerte reaviva la polémica por aborto. El País. Available from: http://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/muerte-reaviva-polemica-aborto.html 2016 Feb 24.