Abstract

Water Users Associations (WUAs) have been introduced in Gash Delta Agricultural Scheme (GDAS) in 2004. The level of participation and performance of these associations have been influenced by many factors. The purpose of this paper is to measure the level of participation and to identify the factors influences the performance of WUAs in GDAS in eastern part of Sudan. Field visits, questionnaires, and focus group discussions were conducted during 2013/2014 crop season. The participation of farmers was classified to full, average, less and no participation. The results indicated that WUAs fully participate in water distribution and clearance of agricultural land. It is found that WUAs partially participate in provision of finance, seeds, attend flooding time and report water breakages. WUAs less participate in maintaining of bonds and not yet contribute in mapping of wetland. The results also indicated that WUAs have influenced by the lack of cooperation with other related institutions working in GDAS. The obtained results will contribute in improvement of participatory spate system management.

1 Introduction

Over the last three decades, a large number of countries around the world have adopted programs to transfer management of irrigation systems from government agencies to Water Users Associations (CitationJohanson, 1999; CitationKloezon, 2002). This is to fill in the gap between expected and actual performances of irrigated schemes and finding appropriate institutional arrangements whereby the farmers could play a major role in sustaining irrigation system operations. Experience on water management predicts that the potential benefit of the improvement of water management is by giving farmers a greater role in managing irrigation water. Management of the spate system requires arrangements for various management functions which cannot be achieved without strong farmer organizations. The philosophy behind WUAs is that the involvement of farmers in management of irrigation systems will encourage them to manage their irrigation system. Involvement of farmers in water management considered the only way to reduce pressure on thinly stretched government finances and at the same time ensuring the long-term sustainability of irrigation system. CitationPerret (2002) indicated that after transferring irrigation management responsibilities to WUAs, social development, economic growth, ecological integrity and equal access to water as key objectives of the new water resources management can be achieved. Spate management, by its nature, is very risk-prone and requires high levels of cooperation between farmers to divert and distribute flood flows. Spate system in Gash requires a lot of effort from farmers to operate and maintain, as uncontrolled flows with unpredicted volumes require a large effort in re-constructing canal diversions, leveling of lands, repairing scour damage and in some cases removing sediment deposits. More than any other type of irrigation, participation of farmers is key factor of the success of spate irrigation management. The need for collective action is the basis of traditional spate irrigation practices, and the viability of spate-systems is determined by the level of participation in flood management. WUAs are fundamentally a participatory, bottom-up concept (CitationSonal, 2003). However, they have existed for centuries and have received particular attention in recent decades as a development tool.

In many countries, increasing water use efficiency has been considered due to shortage of water and limited government finance to irrigated agriculture. For these reasons, participatory irrigation management through WUAs has been emerged. Without farmers’ effective participation, water will be diverted to empty land. Potentiality of WUAs constitutes encouraging point as internationally; results of farmers’ participation are becoming increasingly viable according to CitationFarbrother (1991), CitationBashier (2009), CitationMeinzen and Subramanian (2002). CitationQiuqiong et al. (2010) confirmed that there have been few empirical studies to assess the effectiveness of water management reform. The performance of the spate irrigation sector in Sudan is expected to be low and there are attempts for improvement through WUAs. Low spate irrigation efficiency can be attributed to an ineffective water management due to low participation of farmers (CitationBashier, 2009). In Sudan, since 2002, the emphasis has been focused on performance outcomes and institutional reforms in Gash Delta Agricultural Scheme (GDAS) and Gezira schemes. This resulted in the transfer of numerous irrigation subsystems to Water Users Associations. However, WUAs formed under deteriorated irrigation infrastructure and severe financial problems.

Spate irrigation is an old practice of which flashy spate floods controlled and used for cultivation. It is a unique form of irrigation, predominantly found in arid and semi-arid regions (CitationFAO, 2010). Spate Irrigation management is crucial mainly for agricultural production of the poor. It supports livelihoods of rural population in the Middle East, West Asia and North and East Africa. According to CitationPerry and Bucknall (2009), spate irrigation systems account for approximately 2.5% of irrigated land in Sudan. In Gash spate irrigation system, WUAs were established and supported by IFAD since 2004 under the institutional reform of Gash Sustainable Livelihoods Regeneration Project (GSLRP). A number of 92 WUAs were formed. Each WUA elects two representatives to the overarching WUA organization at the scheme level. CitationFadul et al. (2012) have showed that there are many challenges facing WUAs in GDAS. CitationBashier (2009) indicated that the WUAs in GDAS have had obstacles of inadequate funding, lack of revenues and technical capacity.

Since the formation of WUAs in 2004, the performance of WUAs is not well understood. CitationLee et al. (2015) have assessed WUAs in GAS using few performance factors that are mainly based on the five principles that are originally defined by CitationWang et al. (2010). In this study, many performance factors and different datasets were used to assess the performance of WUAs. The purpose of this study is to identify the factors that have reduced the performance of both WUAs and spate irrigation efficiency in GDAS in order to improve the livelihoods of inhabitants in the scheme.

1.1 Spate irrigation management problems in Gash

Worldwide, spate irrigation systems are hindered by great variations and unexpected volume and frequency of floods, lack of prediction models, shorter time warning system and occurrence of disastrous flood that often results in considerable damage to irrigation networks, property and land. Flood flows are usually fast and contain great amounts of sediment loads drifted from the catchment and eroded from the river channel. Spate irrigation systems in GDAS suffer from a severe invasion of Mesquite (Prosopis juliflora (SW.) DC.) (CitationIFAD, 2004). Mesquite occupies a larger area of the scheme and it has being out of control. Manual work is dominant in Gash because of unavailability of agricultural machinery. Influential farmers add some areas to the planned ones, which create water distribution problems. Some uneven Mesgas complicate water distribution. Transportation constitutes big problem because of no roads inside the scheme. Lack of knowledge with bylaws, rules and regulations leads to overlap of duties and responsibilities between WUAs and related institutions working in the scheme. WUAs in GDAS lack transparency between executive committees and members. Gash scheme has no council and accordingly a lot of rules and regulations not working because it needs to be approved by the scheme council. Extension in GDAS is poorly equipped in order to contribute effectively in the natural resources management utilization.

1.2 Source of floodwater

Gash River originally is the River Mareb which rises in Eritrean plateau, about 26 km south of Asmara. It flows in a narrow valley until Hykota, then widens into Tesaney-Omhajar sandy clay plains. Then it flows westward to Tesaney and turns northward and crosses Sudan borders at Golsa (about 26 km south of Kassala city) as the Gash River. In the east of Kassala city the Gash River is joined by its only tributary (Khore Abu-Alaga), then dividing Kassala city into two parts northwards to diminish at the Gash Die (about 94 km North of Kassala city). The flows extend over an effective period of 60–70 days from July to September with high sand and silt loads. Gash River dissipates in the terminal fan 100 km north of Kassala city where it provides moisture for natural forests, pasture and seasonal wetlands for crop production. It also recharges the aquifers and fills hafirs (dug out pond) which support stock water points. Downstream from Kassala city, some of its floodwater is diverted into canals from which stems a truncated channel which diverts water into pieces of land known as “Messga”. Each messga is 500 m wide and from few km to 20 km long. There is minimum control on the water flowing over the messga area. Land that had enough water is distributed among the farmers.

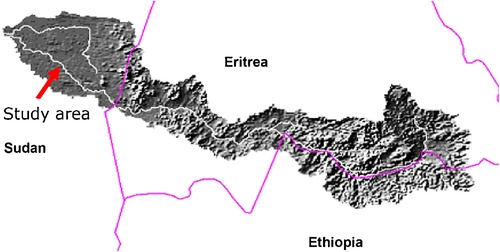

1.3 Study area

The GDAS is located in Kassala province, in the eastern side of the Republic of the Sudan as shown in . This large irrigation scheme was set up by the government in the 1920s to settle nomadic people into a cash economy growing cotton. The climate is semi-arid to arid. It is hot throughout the year with maximum temperature ranging from 34 to 42 °C (May–August) and minimum from 16 to 25 °C (January–April). The average annual rainfall ranges from 260 mm in the southeast to less than 100 mm in the northwest (CitationIFAD, 2003). Rainfall occurs between July and October, and is extremely variable in amount, intensity and distribution. The effectiveness of the rainfall is severely limited by the high evapotranspiration rate (≥2000 mm per year) and it commonly fails to reach the root zone. Spate soils generally have good water-holding capacities with relatively moderate infiltration rates that vary with soil texture, density and soil management practices. The alluvial Gash silt (Lebad) was the dominant soil and had much higher infiltration rates. The soil in GDAS has advantage of the available moisture stored in the soil reservoir.

2 Methodology

Field visit was carried out in January 2013 to assess the visual indicators of WUAs participation in Gash spate system. Observed data during field visits were considered and incorporated. Discussion with farmers was also made on factors influencing their participation in spate system management. Because stakeholders are able to identify and rank the factors influencing their participation, two groups discussion were carried out with stakeholders including farmers who are members of the WUAs, farmers’ union representatives and GDAS officials to identify the factors that are currently influencing performance of WUAs. This method was previously used by (CitationShivakoti and Thapa, 2005). They used farmers’ perception as a tool to identify the effectiveness of institutions. Nine factors were identified and listed including small farmer landholding, low income from agriculture, unfair distribution of resources, absent of training, only one crop, no transparency between WUAs and members, problem in water distribution, Mesga itself in terms of leveling and lack of cooperation between related institutions.

The study targeted Kassala block which includes four irrigation canals: Fota main canal which irrigates 3025 ha, Rabakasa canal irrigates 3655 ha, Tograr main canal which irrigates 9580 ha and Amber branch canal which irrigates 3277 ha. There is no fixed landholding in GDAS because the flooded area is distributed over the number of farmers of WUA each season. Because of similarity of WUAs, the study randomly covered the all 14 WUAs in Kassala block. From them a number of 115 farmers were questioned.

Groups’ discussions were conducted to identify the factors influencing WUAs participation. Questions on identified factors were developed in the form of questionnaire targeting WUAs in Kassala block. Kassala block is accessible and farmers are available to respond to questions. Respondents were requested to give score for each factor. Scoring range was designed to be from 1 to 9. The scoring system was clarified as one for the highest factor influencing performance of WUAs and nine for lowest factor. Then the total scores for each factor was summed and divided by the total number of respondents. The levels of participation of WUAs in spate management were investigated using the same questionnaire. Respondents’ scores were classified to full participation, average participation, less participation and no participation ().

Table 1 Classifications of respondents’ scores.

3 Results

The results showed that, 73% of WUAs are fully participating in clearance of land and 75% in water distribution (). The average participation of WUAs includes attending flooding time (60%), contributing in keeping water to infiltrate (50%), participating in reporting water breakages (60%), participating in provision of finance (48%) and contributing in provision of seeds (40%). WUAs are less participating in maintenance of water bonds and are not yet participating in mapping out of wetland ().

Table 2 Level of WUAs participation in spate irrigation management.

A number of nine factors influencing performance of WUAs in GDAS were identified and evaluated. Absence of cooperation between WUAs and related institutions such as GDAS board, Farmers Union, Gash Training Unit and Ministry of Agriculture, constitutes (71.1%) as the major and top factor affecting the performance of WUAs as shown in . The second major factor (60.4%) influencing performance of WUAs is the Mesga in terms of leveling. The respondents classified water distribution problems as third factor influenced WUAs in GDAS. This followed by lack of transparency between executive committees and farmers particularly in budget itemization and distribution of wetted lands. The factor of one crop dependant has been scored 57.6%. Absence of training for WUAs scored lower than the risk of one crop. Unfair distribution of land, low income from agriculture and small farmer landholdings gives lower scores as factors influencing the performance of WUAs in GDAS.

Table 3 Factors influencing performance of WUAs in GDAS.

4 Discussion

WUAs are fully participating in two important issues in spate system management. Clearance and preparation of agricultural land and water distribution considered the main activities to maximize the benefits from flood systems. It seems that WUAs participation has resulted in cleaner land but still there are some farmers’ organizations waiting for external intervention and they claim that because of high cost they leave their land unclean. Few WUAs members think that government should clean the land on behalf of them. CitationMeinzen (1997) stated that establishing WUAs has not improved the control of farmers over the irrigation system in Ethiopia or which country; however in GDAS, WUAs keep farmers together and encourage them to participate in flood management.

WUAs participate averagely in activities necessary for success of spate-systems such as attending the flood time, take their water turn, report water breakages, provision of finance and seeds. Duration of flood in each land is related to flood waves of Gash River. The rules on depth of irrigation are not common in spate-irrigated areas, but field-to-field water distribution system is practiced. In this distribution system, a farmer takes his turn as soon as his neighbor completes the inundation of his land (CitationAbraham et al., 2010). Therefore attending flood time is curial because flood distribution may lead to conflicts between farmers because of no clear rules of flood distribution. Spate irrigation always takes place in semi-arid and remote environment. There are often very few options for generating income. Financing of agriculture constitutes major obstacle factor for WUAs in GASH or in general. Farming season is very short in GDAS therefore; the majority of farmers generate income from free work such as producing charcoal from mesquite and other free jobs to finance themselves. The most common livelihood strategy is the diversification of the household economy. In addition to a highly variable income from spate irrigated agriculture, households may have one or more source of income from keeping livestock and wage labor and, to a lesser extent, from the sale of handicraft products.

Seeds in GDAS need more attention as few farmers use certified seeds. WUAs are keen to use treated seeds to avoid failure of season. The major treatment is against smut fungus; however, the doses used are below the recommended. Seeds provider with longer insurance is highly required for such risky spate farming system. Few WUAs produce their own seeds from previous crop. Few WUAs borrow the seeds from colleague, others purchase their seeds from the market and the others get the seeds from different unknown sources. The average participation of WUAs in spate system management may be partly explained by the small farm sizes of 1–3 feddans (1 ha = 2.38 feddans) in GDAS. Given the small farm size and the large number of farmers, the benefit of participation that accrues to each farmer likely exceeds the cost.

WUAs are less participants in maintaining water bonds. Poor water bonds may lead to non-equitable distribution of flooded water among the farmers and this constitutes major deterioration of Gash spate scheme. WUAs are not yet invited to attend flooded land mapping which is crucial factor for transparency, cooperation and equity. Wetland is an effective and cultivable land that covered by flood water. As part of the institutions governing flood water use, WUAs should be invited to attend and contribute in wetland mapping and distribution. However this is not yet happens in GDAS.

In terms of the factors influencing the performance of WUAs, the results indicated that there is lack of cooperation between WUAs and other institutions working in GDAS. This constitutes the major factor influencing WUAs participation in spate management. At the time of establishment of WUAs, some institutions fear that these new organizations will take other institutions responsibilities. This creates a gap between the existing institutions and WUAs as new body. Lack of cooperation with other institutions such as Ministry of Water Resources and Electricity (MWRE), Gash Training Unit (GTU), Kassala state Ministry of Agriculture, farmers union and Gash Agricultural Scheme Board slowing down participation of WUAs. Poor leveling of Mesga leads to inefficient water distribution. The poor distribution of water in spate-systems is a considerable source of conflict between farmers. This result agrees well with the findings of CitationLee et al. (2015). Lack of transparency between WUAs and other institutions from one hand and between WUAs and their members from other hand constitutes real problem in GDAS. Lack of transparency means lack of coordination and cooperation and hence unfair distribution of resources occurs. Uncontrolled flows with unpredicted volumes requiring a large effort of cooperation to manage. Lack of transparency between WUAs members comes from the low educational level of the members due to absence of trainings. Low income from agriculture which associated with small landholding farms has been minimally influence the performance of WUAs. This is because most of WUAs members have other sources of income like free work.

5 Conclusion

Although WUAs participate in spate management activities, their involvement in the main issues of spate management is still partial. It seems that WUAs participation have resulted in cleaner land. In spite of weak relations between WUAs and other related institutions working in Gash, it has been observed that WUAs are gradually being accepted by other institutions. Incentive system is required to strengthen WUAs toward effective participation. Finally, strong cooperation between all stakeholders in the scheme including farmers, government and researchers is needed to have strong WUAs and hence sustainable scheme.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Spate Irrigation Network (project of Spate Irrigation for Rural Growth and Poverty Alleviation, Sudan). Also we would like to acknowledge all those who helped us and facilitated the field work in Kassala Blocks.

Notes

Peer review under responsibility of National Water Research Center.

References

- M.H.AbrahamV.S.FrankS.BartWater rights and rules, and management in spate irrigation systems in Eritrea, Yemen and PakistanB.van KoppenM.GiordanoJ.ButterworthCommunity-Based Water Law and Water Resource Management Reform in Developing Countries2010Publisher Wallingford114129 (CABI year 2007)

- E.E.BashierImpact of WUAs on Water Management in Gezira, Gash and White Nile Schemes, Sudan (PhD thesis)2009Water Management and Irrigation Institute, University of GeziraWad Medani, Sudan

- E.FadulB.EltiganiB.AgeelA.HaileSharing Experiences Among Water User Associations in Spate Irrigation Schemes, Regional Workshop Report, Kassala, Sudan2012

- H.G.FarbrotherViews About Privatization of Irrigation Schemes in Sudan. Workshop on Privatization of Irrigation Schemes in Sudan, Khartoum1991

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United NationsGuidelines on Spate Irrigation. Irrigation and Drainage paper #65, Rome, Italy2010

- International Fund for Agricultural DevelopmentGash Sustainable Livelihoods Regeneration Project. Target Group and Project Description2004Prepared by Near East and North Africa Division, Project Management Department, IFADRome

- International Fund for Agricultural DevelopmentGash Sustainable Livelihoods Regeneration Project, Formulation Report 1462-SD2003Project Management Unit, IFADRepublic of Sudan, Rome

- S.H.JohansonChanging the guard in Mexico. Transferring irrigation management to Water Users AssociationsTransactions the Sixteenth Congress on Irrigation and Drainage, vol. 1 EGranada1999

- W.H.KloezonGoing Beyond the Boundaries of Water Users Groups: Financing O&M in Sri Lanka2002International Irrigation Management InstituteColombo, Sri Lanka

- L.A.NgirazieA.I.BusharaJ.W.KnoxAssessing the performance of water user associations in the Gash Irrigation Project, SudanWater Int.201510.1080/02508060.2015.1072677

- D.R.MeinzenWhat affects organization and collective action for managing resources? Evidence from canal irrigation systems in IndiaWorld Dev.3042002649666

- D.MeinzenFarmer participation in irrigation – 20 years of experience and lessons for the futureIrrig. Drain. Syst.111997103118

- S.PerretWater Governance for Sustainable Development. Approaches and Lessons from Developing and Transitional Countries, London, Sterling, U.K.2002

- C.J.PerryJ.BucknallWater Resource Assessment in the Arab World: New Analytical Tools for New Challenges2009The World BankMiddle East and North Africa Region97118 (Chapter 6)

- H.QiuqiongW.K.JinxiaE.WilliamR.D.ScottEmpirical assessment of water management institutions in northern ChinaAgric. Water Manag.982010361369

- G.ShivakotiS.ThapaFarmers’ perceptions of participation and institutional effectiveness in the management of mid-hill watersheds in NepalEnviron. Dev. Econ.102005665687

- B.SonalHow does participatory irrigation management work? A study of selected water users’ associations in Anand district of Gujarat, western IndiaWater Policy1520132003223242

- J.WangJ.HuangL.ZhangQ.HuangS.RozelleWater governance and water use efficiency: the five principles of WUA management and performance in ChinaJ. Am. Water Resour. Assoc.4642010665685