Abstract

This article seeks to initiate research around the potential roles of the accounting profession for tackling the challenges of the vulnerable. Its backdrop is the current consideration of the profession’s public interest role. The importance of dialogue around the public interest role is evidenced by the increasing levels of vulnerability, even within developed countries. Accounting underpinned by broader values has potential to provide knowledge of issues relating to the vulnerable. However, the accounting profession has only engaged with such potential to a limited degree. The article overviews existing knowledge and areas within which more research is required. In order to illustrate the potential for such research, initial findings from two case studies of homelessness (an example of the vulnerable) provide evidence as to the importance, and challenges, of accounting for the vulnerable. This article highlights the need to: take a principles-based approach in defining the vulnerable, undertake an accounting that reflects the lives they value, acknowledge that there are different ways for addressing these issues, recognise that an absence of perfect numbers should not become a barrier to action, and that accounting for the vulnerable is one way that the accounting profession may discharge their public interest roles.

With our globalized economy and sophisticated technology, we can decide to end the age-old ills of extreme poverty and hunger. Or we can continue to degrade our planet and allow intolerable inequalities to sow bitterness and despair. (United Nations Citation2014, p. 3)

1. Introduction

What the public interest role of the accounting professionFootnote1 should be is subject to ongoing debate (Dellaportas and Davenport Citation2008, Killian and O’Regan Citation2020, Spencer Citation2020). With this backdrop of the debate, it is the aim of this article to initiate more research on the potential for accounting and the accounting profession to have a role in tackling the global challenges of the most vulnerable. After all ‘what we choose to measure is ultimately a manifestation of what we care about’ (Glasser Citation2019, p. 63). In so doing, this article will contribute towards calls made (Killian and O’Regan Citation2020) for research that examines accounting’s potential to mobilise the common good.

For the current and ongoing consideration of the accounting profession’s public interest role to provide a backdrop to this article, an understanding of the differing perspectives is required. The dominant perspective in this debate could be considered as traditional, is based on neo-classical economic underpinnings, and is not only influenced by commentators such as Friedman (Citation1962) but is also part of what Glasser (Citation2019) refers to as the ‘dominant metanarrative’. This perspective argues that as long as the accounting profession continues to perform the role it always has, there will be alignment in terms of fulfilling the public interest role.Footnote2 That is, the public interest role of the accounting profession is served through their core remit of ensuring that capital allocation is optimised, and also ensuring that the tax system functions as intended. Further, the accounting profession serves the public interest through decreasing information asymmetries and related issues (e.g. adverse selection), reducing agency problems, and thereby helping organisations to finance positive net present value projects. It is believed that this creates employment and other such positive, economic-related, outcomes. And, finally, that these outcomes will then increase the tax base that the government has at its disposal to invest in schemes that alleviate the issues affecting the most vulnerable.

For this dominant perspective to hold requires first that there are positive, economic-related, outcomes; and, second, that the corresponding use of the tax base creates benefits for all and, thereby, nurtures greater equity. However, evidence shows that, while global material prosperity has increased dramatically over the last century, this has not occurred in an equitable way, with more people than ever now considered to be vulnerable (Stiglitz Citation2012, Citation2015, Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010). An Oxfam report in 2016 outlined how, in 2015, 62 people collectively had the same material wealth as the bottom fifty percent of the world’s population (Hardoon et al. Citation2016). In 2018, again based on Oxfam data, this had fallen to just 26 people (Lawson et al. Citation2019). The decrease was partly due to the 26 people becoming more financially wealthy. But, problematically, it also relates to the bottom fifty percent of the world’s population becoming less financially wealthy. For this to happen suggests that the positive, economic-related, outcomes and the corresponding use of the tax base is benefiting a powerful few (Conceição Citation2019, Veldman Citation2019). For example, evidence suggests that the current use of corporate governance mechanisms, including accounting, has resulted in an ‘explosion’ of rewards to executives at the expense of others (Clarke et al. Citation2019). By implication, through using the same arguments of the dominant perspective, the accounting profession is currently failing in terms of serving its public interest role.

The examples presented above are further reflected in many other accounts that suggest the profession is failing in relation to serving the public interest (Killian and O’Regan Citation2020, Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019). Clarke et al. (Citation2019), amongst others, argue that the dominant perspective merely serves the interest of shareholder maximisation, which is incommensurable with creating greater equity.Footnote3 Extreme cases, in particular, shed light on how accounting is utilised to promote corporate interests at the expense of the public interest (Killian and O’Regan Citation2020). No better case exemplifies this than Du Pont and its use of the chemical Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) (Barry et al. Citation2013, Hoffman et al. Citation2011). Despite over many years having undertaken their own research on the dangerous nature of the ‘forever’ chemical PFOA, Du Pont filed all their required corporate accounts without once mentioning this issue. However, it is now estimated that all humans have some level of this chemical present within their bodies. Such episodes, which undermines trust in the accounting profession, has resulted in questions being asked from within the profession as to whether the dominant perspective still ‘holds water’ (Spencer Citation2020, p. 1).

Given the questionable relevance of the dominant perspective, there have been calls for development of, beyond its current vague and ambiguous nature, what the public interest role should be, to whom is it owed, and how will the accounting profession serve it (Dellaportas and Davenport Citation2008, Killian and O’Regan Citation2020). When analysed from a holistic perspective, these questions become complex. Specifically, a more circumspect view requires an acknowledgement that organisations and the public have intricate interdependencies that necessitate broader accountabilities, and which go beyond what is possible to be reflected in a legal contract (Millon Citation1993). This is echoed in an interview conducted with Richard Spencer from the ICAEWFootnote4 in which he stated:

Our members may sit here in vertical sort of businesses, but as a horizontal professional they have an overriding duty to serve the public interest. What would that look like and how would that play out, and how could that join them up with other professions? Is that what makes us a profession?

the organisational and national catastrophes and personal hardships that have come with the global financial crisis, issues with pension funds, multinational corporate tax avoidance and national austerity budgets, just to name a few, it is clear that accounting has responsibilities that affect the living conditions of billions of people globally.

Moreover, with the wide reach of accounting, this suggests that the inverse is also possible. That is, as accounting is associated with so many different aspects of inequity, it has the potential to assist the efforts of, and to hold to account, those that have the ability and resources to alleviate such hardships. For some, as is exemplified in the commentary that accompanies this article (Deeson Citation2020), such things can be straight forward, given the aims of their organisation. For others, however, this may present some challenges. To date the accounting profession has been criticised for not taking as seriously as it might this type of public interest role, rather utilising any efforts for its own legitimation (Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019).

The need for more research in relation to accounting for the vulnerable is unsurprising given that in essence it is the examination of an important aspect of social sustainability. Social sustainability is a ‘wicked problem’ that has over the history of humanity been ‘one that has bedeviled our species with its challenge and promise for millennia’ (Glasser Citation2019, p. 38). By wicked problem it is meant issues and challenges that are ‘persistent, complex, and difficult or perhaps even impossible to solve’ (Farrell Citation2011, p. 335). They are of such complexity that even defining them, let alone finding solutions for them, often proves to be a practical impossibility (Churchman Citation1967). As such there is no clear, concise or ‘right’ approach to their resolution (Bebbington and Larrinaga Citation2014). The question, therefore, is how do we approach and address the wicked problems of the most vulnerable, and what role can the accounting profession take?

The starting point is to note that wicked problems require a plurality of research approaches, as argued for by Costanza (Citation1989), in order that different aspects of the relevant issues can be explored. Such an approach enables the failings of one research perspective to be overcome by the strengths of another. Reductionist approaches, which underpin the dominant perspective to the public interest role, are not, if used in isolation, fit for purpose in developing our understanding of accounting for the vulnerable. For example, Millon (Citation1993) argues that many of the social costs associated with organisations stretch considerably beyond the more obvious and quantifiable impacts that it has on the public, thereby rendering a reductionist approach too simplistic. This includes, as is often seen in reductionist approaches, limitations to arguing for more data (see for example Leuz Citation2018). As Glasser (Citation2019, p. 35) notes ‘wicked problems are simply not amenable to strict optimization by black boxes, however sophisticated, objective, and data-driven they might be’.

It will be argued throughout this article that accounting for the vulnerable is an area that needs to be more holistically assessed within the broader debate over the public interest role. This will include, given the overwhelming evidence of the current failings of our economic systems to provide equitable outcomes, re-evaluating the taken for granted assumptions over what accounting is and can be. Unpacking the ‘dominant metanarrative’ and advancing accounting for the vulnerable will require an acknowledgement that ‘because every wicked problem is unique, evolving, and always partly wild, there is limited potential to learn directly by trial and error or generalize “solution” strategies from past practice in a literal sense’ (Glasser Citation2019, p. 36). Rather, a more appropriate approach to take is ‘skilful muddling’, with emphasis on ‘learning how to think, plan, and act in more anticipatory and adaptive ways’, in order to ‘unearth and face the root causes of interconnected […] challenges [and] address their wicked nature’ (Glasser Citation2019, p. 64). Such an approach is consistent with those that have been called for within social and environmental accounting for some time (Gray Citation1998, Citation2002).

In order to illustrate the need for more research on accounting for the vulnerable, the following focuses on two main questions. The first question is: what is the current knowledge, and potential, of accounting for the vulnerable? The second question is: what are the implications for the accounting profession in serving the public interest? The first question seeks to understand the extent to which we understand this topic. As discussed below, to even explore this question requires considerable dissection and examination of the concepts and issues involved. The purpose of the second question is to link the first back to the ongoing debate over the public interest role.

In order to answer the two main questions, they are broken down into a further six sub-questions. The first of these sub-questions is what or who do we mean by the ‘vulnerable’? The first step in accounting for something is for that very thing to be defined. The second sub-question is: why should the accounting profession care? Even with the entity defined, it is only once motivation is provided that any action, especially related to a public interest role, will be undertaken. This is an acknowledgment of the statement above by Glasser (Citation2019, p. 63) that ‘what we choose to measure is ultimately a manifestation of what we care about’. The third sub-question asks: what literature already exists? By examining the existing literature, it is possible to make an assessment of the state of knowledge and what this implies for the potential of accounting for the vulnerable. The fourth sub-question is: what accounting is, or could be, used? Knowledge of what is already being used can provide understandings of how to approach these issues, particularly in terms of what has been found to work, and what has not. The fifth sub-question is: what accountabilities are, or could be, constructed? The establishment and discharge of accountabilities is at the heart of taking the public interest role seriously. The final sub-question asks: what values underpin these issues? This is premised on the assertion that if accounting is undertaken with only a focus on financial values, it is unlikely that broader values, which relate to issues of the vulnerable, will be considered.

While this article mainly relies on existing knowledge and literature in addressing the above questions, the initial findings of two case studies are also presented to provide illustration of the potential in this type of research. These case studies are extracted from a larger, ongoing research project that focuses on accounting for the vulnerable, with a specific examination of homelessness. In using these case studies, it is stressed that homelessness is just one aspect of who the most vulnerable are, as further outlined below. The first case study examines the complexities of dealing with issues associated with homelessness in London, UK, with a particular focus on Lewisham Council. The second is of Auckland, New Zealand, where measures of prosperity, such as GDP, are masking an ever-increasing homelessness crisis.

The questions and illustrative case studies provide a platform for suggesting areas in which fruitful research may be done to further our understanding of accounting for the vulnerable. What follows is rooted in accountants being experts in the production of visibility, in terms of collecting, aggregating, analysing and communicating information (Jollands Citation2016). This requires evaluating the relevance of some data compared to other data. Through undertaking this process, accountants are the agents for creating awareness over what they deem to be relevant. One example may be the externalities, caused by their organisations, which effect the most vulnerable. If these were deemed to be relevant then they have the opportunity to create awareness of the issues involved. This, in turn, may change the values that are being focused on within society. However, as Gray (Citation1998, Citation2002) has advocated, this will require the accounting profession to imagine new possible accountings.

An important consideration here concerns what is the entity that is being accounted for (Bebbington and Unerman Citation2018, Ferguson et al. Citation2017, Medawar Citation1976). Usually the entity that is accounted for is an organisation. However, there is nothing stopping this entity being something different (Birkin Citation1996, Cooper et al. Citation2005, Gray et al. Citation2014, Spence Citation2009). For example, it could be a suburb, a council area, a city, a nation, or as is argued here, the vulnerable themselves. By focusing on a different entity, better understandings may develop in relation to the types of accountability that needs to be established for there to be any chance of addressing such challenges. Arguably, it is here that the accounting profession has an opportunity to serve the public interest. However, that said, it is not necessarily going to be easy to serve the public interest role through accounting for the vulnerable. This is a wicked problem and there are no quick fixes. Notwithstanding, at the very least, more research about these issues is needed.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In the next section, there is an outline of the underlying concepts relied upon throughout. This is followed by discussion of who the vulnerable denotes. Given the issues involved, a principles-based definition is established, rather than attempting an exhaustive list of the vulnerable. Taking such a principles-based approach requires that accounting for the vulnerable reflects the lives they value. The fourth section covers why the accounting profession should engage with these issues. This includes understanding that there are different approaches, which could be taken to address these issues. The fifth section examines, with reference to the extant literature, how accounting is implicated in these issues. This is followed by an examination of one aspect of note from our initial field work in two case studies. That is, given one of the foundations of accounting is to count things (Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019), how do we count the homeless? Issues arise because of having no set definition of homelessness, but also this becomes even more complicated due to the nature of what is being counted. This, therefore, recognises that an absence of perfect numbers should not become a barrier to action. A conclusion is then offered through bringing the wider discussion back to thinking about the public interest role of the accounting profession. Specifically, it is argued that conducting more research on accounting for the vulnerable is one way in which the accounting profession can aim to discharge their public interest roles.

2. Underlying concepts

In this section there is a brief discussion of some underlying concepts, in order to situate what follows in this article. This, as context, starts with an examination of the nested system view.

2.1. The nested system view

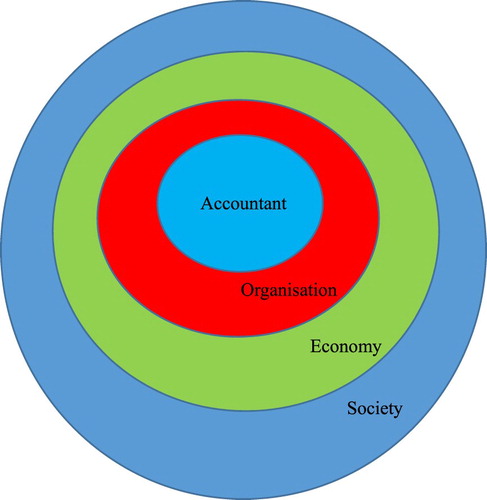

To place things into context, what follows is a brief insight into the idea of a ‘nested system’ (see Jollands Citation2016, Wackernagel and Rees Citation1996), taken from the sustainable development literature. Referring to below, an accountant can be viewed as located within an organisation which, in turn, exists within our economy. But, importantly, the economy is a sub-set of society. In other words, without society there would be no economy. Conversely, with no economy there would be no organisations or accountants.

It is with such an understanding that a debate around the public interest role of accountants starts to make more sense. That is, if the accountant merely serves the organisation, then in the long term they may be undermining the very society that sustains their organisation. As mentioned already, for some accountants the very nature of their organisation embeds this understanding of a nested system in the day to day remit of what they do. For others, however, this understanding may not appear to be as straight forward, especially given the pervasiveness of the dominant perspective on what the public interest role of the accounting profession is. At times tensions may arise between an organisation’s focus and other broader values. It is, therefore, a question of how do, or even should, accountants attempt to reconcile the various values that may be in tension within what is being accounted for? This is not to be taken as a dichotomy of financial values versus other values; financial values are clearly important in terms of resourcing responses to these issues. However, having an exclusive focus on the financial, or in other words, ‘throwing money at the issue’, will not get appropriate results. An important aim of this article is to examine the need for broader and new accountings, as advocated for by Gray (Citation1998, Citation2002). This is, however, premised by what it is meant by the term ‘accounting for the vulnerable’, a discussion now turned to.

2.2. Variable meanings of accounting for the vulnerable

There are clearly problems in the way accounting has been utilised in relation to the vulnerable in the past (see for example Graham and Grisard Citation2019). However, there still remains potential for it to be utilised in efforts to alleviate the hardships related to such issues. The starting point, it is argued, is to question what is meant by ‘accounting for the vulnerable’? Moreover, this might have at least three different meanings.

The first meaning concerns ensuring that people are empowered to stop the creation of the vulnerable. This is akin to financial accounting, which has the aim of ensuring that managers do not exploit the resources of the owners for personal benefit. The second meaning is about providing an understanding of the situation and issues of the vulnerable. This is akin to management accounting, which has the aim of providing an understanding of the state of play for organisational decision makers. The third meaning is a tool for the vulnerable to use themselves, in order for their concerns and issues to be made visible in a way that represents their perspective. This is akin to practices within social and environmental accounting, such as shadow accounting (see for example Dey Citation2003, Citation2007, Tregidga Citation2017), that aim to provide broader understandings of situations in order that more than one perspective may be taken into account.

Throughout this article all three of these meanings will be implicitly explored. One challenge is how all three of these meanings might be brought together in order to provide ways forward in addressing the issues around vulnerability. As Glasser (Citation2019) argued, a diverse set of accounts is required to even start understanding such wicked problems. Part of this will be considering what could and should be the roles of broader values within these accountings, and whether power relations dictate what is ultimately possible (Spencer Citation2020). Situations where one type of value may end up ‘crowding out’ other important values (Sandel Citation2013) require particular examination. But, due to the complexity of such wicked problems, the aim should be to highlight the potential consequences of these situations, thereby prompting debate about how things could, and often should, be otherwise (Law Citation1992). Hence, the research being called for here should not seek to provide a ‘solution’ or a ‘framework to conquer all frameworks’. Rather, it should aim to create debates and knowledge generation on issues surrounding the accounting related to the most vulnerable. For now though, there follows an explanation for why it is equity and not equality that such research should engage with.

2.3. Equality and equity

Equality (inequality) and equity (inequity) are often used interchangeably (see for example Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019), or the subtle differences between them remains undefined (see for example Marriott and Sim Citation2019). While this is often unproblematic, for the purposes of this article it is important to make a distinction between the two, with equity being the primary focus here. To clarify the difference, it should be noted that equality is focused on providing everybody with the same (Sen Citation1993, Citation1999). In other words, the standardising of what everyone gets and has. Examining the success of many Japanese businesses illustrates how they reject standardisation, because such a focus can only result in sub-optimal outcomes (Hiromoto Citation1988, McMann and Nanni Citation1995). Hence, avoiding sub-optimal outcomes in terms of the vulnerable requires a focus on the specific needs and issues of those involved. This suggests that it is better to think in terms of equity.

Equity is related to each individuals’ abilities and acknowledges that every person will have advantages and disadvantages that relate to their uniqueness. Equity, therefore, shifts the focus to providing the capabilities for each individual to excel, with their given set of abilities taken into account. The focus on equity is in line with Sen (Citation1993, Citation1999), who argues that development should be focused on expanding the opportunities that vulnerable people have rather than the goods to which they have access. Tweedie and Hazelton (Citation2019, p. 1994) exemplify this by noting that ‘to provide able-bodied and paralysed people the same opportunities to access public spaces, society must allocate a greater proportion of social resources to the latter’. Hence, in terms of accounting for the vulnerable, focus needs to be on providing equitable access to opportunities, an argument that is expanded in the next section.

A focus on equity, rather than equality, is a particular challenge for accounting. The focus of any action that seeks to improve equity must be on the individual. In contrast, accounting needs to standardise, categorise and group people in order to make them calculable and, thereby, financially valuable (Bisman Citation2012, Miller and O’Leary Citation1987, Wällstedt Citation2020). As such, equality, with a focus on standardised outcomes, is more compatible with the processes of accounting. The danger, therefore, is that, if the focus becomes the technical accuracy of the accounting, sub-optimal outcomes will become the norm (Lapsley Citation2009, Wällstedt Citation2020), a point returned to in the penultimate section of this article.

Before proceeding to discuss accounting in terms of (in)visibility, one further, related point is pertinent. It has been argued that accounting in the past has been utilised to normalise, rationalise and reinforce wealth inequality (Graham and Grisard Citation2019, Killian Citation2015, Walker Citation2008). However, wealth inequality is just part of broader notions of equality (Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019). This implies that with equity care needs to be taken so that accounting does not end up justifying the entrenchment of inequity. Rather, the focus needs to be on broader values beyond the financial.

2.4. Visibility, invisibility, and transparency

The final concepts that need to be explored are visibility and invisibility, with a distinction also made to transparency. Visibility is what provides the potential for the accounting profession to have an important role within addressing the inequities of the vulnerable. Specifically, accountants are experts in the production and the use of information, to create visibility over certain things. Traditionally this has been mainly in relation to financial and management information but, as is seen through such initiatives as the GRI and Integrated Reporting, this remit is starting to broaden (Jollands Citation2016). As accounting broadens its focus to account for values beyond the financial, it has potential to improve the understanding of relevant issues, which is the first step in formulating specific actions. However, the effectiveness of such actions will be related to how well the issues are understood – no easy task in relation to wicked problem. Hence, new accountings (Gray Citation1998, Citation2002), with broader values underpinning them, have the potential to provide understandings in relation to the vulnerable.

Through selecting what is accounted for, and thereby made visible, such processes implicitly select what remains unaddressed, the invisible (Jollands et al. Citation2018, Rahaman et al. Citation2004, Spencer Citation2020, Wällstedt Citation2020). In relation to the three meanings of accounting for the vulnerable, if only one of these types of accountings is used to provide visibility then other important aspects may remain invisible. As argued by, amongst others, Cooper and Johnston (Citation2012), more accounting information, per se, doesn’t necessarily result in increased accountability. Hence, accounts alone, no matter how well they are constructed, are unlikely to provide the necessary visibility.

The analogy of the problems of plastics within the oceans exemplifies this point. It has been known for a long time that the amount of plastics within our oceans is problematic. There have been many accounts of this produced over a large number of years. One example is Chris Jordan’s Midway Project,Footnote5 which, through the use of photographic evidence, provides an account of the impacts of plastics on ocean-going birds. Nevertheless, even with such accounts, how much visibility was created over the issues of plastics in our oceans? It was not until the issue became highlighted in the documentary ‘Blue Planet 2’ (Honeyborne et al. Citation2018) that any meaningful action began to take shape.Footnote6 In effect, David Attenborough, the narrator for this documentary, became the spokesperson (Callon Citation1986) for the oceans and brought visibility to the issues of plastics.

This raises the question as to who will be the spokesperson for the vulnerable. Is this a role for the accounting profession, as part of serving their public interest role? Will, or even should, the accounting profession do anything about this? There are inherent dilemmas, especially given it is a wicked problem, in terms of how to act to address the increasing levels of vulnerability observed. However, what is suggested here, through more research, is better understanding of whether accounting for the vulnerable is something that the accounting profession could and should use their expertise for. Could it be that the accounting profession might lead-by-example?

What also needs to be acknowledged, and especially drawing on the research of Roberts (Citation2009, Citation2018), is that this is not the same as the accounting profession becoming advocates for increasing levels of transparency. It has been long established, for instance, within the social and environmental accounting literature (Gray Citation1992, Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2015, Wiseman Citation1982), that some organisations release increased levels of information in an attempt to get stakeholders to focus on certain positive aspects of their operations (Roberts Citation2018). This is in order to keep the attention away from more negative aspects of their operations (Cooper and Johnston Citation2012, Roberts Citation2009). Hence, transparency is not the same as creating visibility over issues, as it (usually) involves the consolidation, and thereby de-contextualisation, of information that obfuscates the very thing that is trying to be accounted for (Roberts Citation2018, Wällstedt Citation2020). Accounting for the vulnerable implies a focus on their perspectives and their way of seeing the world. The next section explores what, or more precisely who, do we mean by the vulnerable.

3. What (or who) do we mean by the vulnerable?

This section seeks to examine what, or more specifically, who do we mean when we refer to the vulnerable? While there are many established definitions, they typically seek to provide exhaustive categorisations of who the vulnerable are. This is exemplified by the definition contained within the United Nation’s sustainable development goals, where vulnerable people ‘include all children, youth, persons with disabilities (of whom more than 80 per cent live in poverty), people living with HIV/AIDS, older persons, indigenous peoples, refugees and internally displaced persons and migrants’ (United Nations Citation2015, p. 8). Rather than utilising a categorical definition, it is argued that a more apt approach is to consider under what conditions someone can be thought of as vulnerable. In other words, a principle-based definition.

The argument for a principle-based approach is grounded in how problematic, and potentially short-sighted, it can be to create such an exhaustive list in light of the wicked problem nature of social sustainability (Glasser Citation2019). An analogy for this need is provided by the use of a conceptual framework in financial accounting. A conceptual framework, as for example provided in the International Financial Reporting Standards, is a set of principles that provide guidance to an accountant in terms of how best to record any given transaction. The need for such a conceptual guide relates to the complexity of business and the infinite variety of transactions that an accountant may need to record. There is an impossibility to providing a rule about how to record every potential permutation, hence the need for principles to provide guidance. Given the complexity of our societies, it is argued that there is an impossibility to providing an exhaustive list of whom may be vulnerable, and with a risk that specific groups or individual vulnerable people may be missed out. After all, as Glasser (Citation2019) notes, there are a multitude of dimensions to well-being, and therefore vulnerability, with a corresponding large number of measurements that are promoted as means to identify societal levels of success in addressing these issues. However, such categorisations and calculations removes the focus from the entity of importance (Miller and O’Leary Citation1987, Wällstedt Citation2020), the individual vulnerable person. Thus, it makes more sense to utilise a principle-based approach that provides a guide as to under what conditions a person can be considered to be vulnerable.

In developing a definition, the Nobel Prize winning work of Sen (Citation1999) is drawn upon. Sen argues that it is more useful to understand development as the expanding of substantive freedoms rather than the improvement in some form of proxy, such as GDP,Footnote7 that tries to measure progress in this area. For this article, it is how Sen defines substantive freedoms that is of most use. He defines substantive freedoms as ‘expansion of the “capabilities” of people to lead the kind of lives they value – and have reason to value’ (Sen Citation1999, p. 18). This aligns with arguments concerning the use of the term ‘equity’. Equity focuses on the importance of creating conditions where individuals are given the capabilities (which relate to their context) to utilise their abilities (which relate to their personal skills) to live lives that, from their own perspective, is one of value. In effect this means that the focus is not on trying to help every person to the nth degree. Rather, it is about creating the conditions under which every person, based upon their own unique abilities, has the opportunity to live a fulfilling life, unhindered by detrimental conditions that are imposed, or they find themselves in. As such it focuses on what individuals are able to do and removing the barriers that are placed in the way of them doing so (Glasser Citation2019). With reference to the nested system view, this aligns the public interest role towards the organisation, and in turn the economy, striving to allow all people to obtain a certain standard of living. As Martins (Citation2015) points out, both Adam Smith and David Ricardo advocated for subsistence levels of existence to include the capabilities of people to reach a standard of living that was reasonable, rather than minimal. Although, it should be stressed that this does not mean equating standard of living to the amount of consumption, but rather to levels of well-being (Glasser Citation2019, Killian and O’Regan Citation2020, Schumacher Citation2010).

Drawing from the work of Sen (Citation1999), the vulnerable are defined as individuals or groups of people that are suffering from, or who are at significant risk of increased, unfreedoms. This includes, but is not limited to, people whose freedoms are affected by poverty, tyranny, poor economic opportunities, systematic social deprivation, neglect of public facilities, intolerance, or over activity of repressive states. Further, this principle-based definition highlights that the vulnerable are created by many of the issues that are currently plaguing our societies, such as modern slavery, conflict minerals, homelessness, inequitable concentration of resources, war and refugee crisis. Many of these unfreedoms and issues, if not all, fully or partially result from the way in which our economic activity, and thereby the organisations involved, is undertaken.

Given the nested system view, outlined above, the accounting profession are implicated, at an individual level, if the organisations they are employed by or the work they do is responsible for creating such unfreedoms or issues. As illustrated in the commentary that accompanies this article (Deeson 2020), some in the accounting profession have resolved this through specifically working for organisations or undertaking roles that have a direct remit to address these unfreedoms and issues. In this respect Nelson (Citation1993) notes:

Accounting can be what accountants do, what they aspire to do, or at least what they should aspire to do. But what of late are these achievements and ambitions? How do they cohere and defend themselves? And when they conflict, how can accountants figure out what to do? (p. 207)

It is interesting to note that this quote, from 27 years ago, suggests that for most in the accounting profession the situation is not so straight forward. This may be due to having personal beliefs that align with the dominant perspective of what their public interest role is, working for an organisation that they feel powerless to influence, or for a multitude of other complex and complicated reasons. While the next section analyses reasons why all the accounting profession has an interest in working towards alleviating unfreedoms, for now it is enough to say that this quote demonstrates that the need for more research in this area has been around for quite some time.

The definition of the vulnerable, with its purposeful focus on the individual, suggests that one area in particular need of more research is whether the vulnerable themselves could or indeed should become an entity to be accounted for. This borrows from Birkin (Citation1996), who in turn draws upon Leopold (Citation1968) to argue for ecological objects being made the entity that is accounted for. Operationally this would require that any organisations or individuals that become associated with the vulnerable must contribute to the account of how their substantive freedoms are, or are not, being expanded. The account will, therefore, address how the ‘capabilities’ of these people to lead the kind of lives they value are, or are not, being put into place.

It is of importance that in producing such accounts that the perspectives of the vulnerable are the focus. This is complicated by perceptions of there being ‘deserving’ and ‘underserving’ vulnerable people, with the former more likely to receive assistance than the latter, who are deemed to be responsible for their own situation (Eubanks Citation2018, Mechanic and Tanner Citation2007). However, if organisations remain the entity to be accounted for (Killian and O’Regan Citation2020), the voices, concerns, perspectives and needs of the vulnerable may become swept aside in the boundary constructing efforts of those that get to produce the accounts of their own activities (Jollands et al. Citation2018). This is supported by both Baker (Citation2014) and Sargiacomo et al. (Citation2014), whose investigations of relief efforts of those that were made vulnerable by natural disasters found that the deployment of traditional accountings, focused on organisations, detracted from providing the best possible outcomes for those most affected. This observation reiterates the need for ‘new accountings’ (Gray Citation1998, Citation2002, Gray et al. Citation2014) that give voice to the vulnerable and focuses on their concerns, perspectives, and needs (Gore Citation2015, Medawar Citation1976, O’Dwyer and Unerman Citation2016).

An example that assists in explaining why we need to account from the perspective of the vulnerable is that it may appear that some people embrace vulnerability, if we look at them through our own lens and our way of seeing the world. As per the example of travellers, what we might consider to be vulnerability, could to them be the kind of lives they value and have reason to value. Hence, as exemplified by travellers, we need to take care not to impose ‘solutions’ that are related to our perspectives and our beliefs about what makes a valuable life. This resonates with the concerns over accounting’s focus on categorisations and calculations, which removes the focus from the entity of importance (Miller and O’Leary Citation1987, Wällstedt Citation2020). If this was the approach, it may result in increasing their unfreedoms rather than putting in place the capabilities they require.Footnote8 Therefore, this suggests that to be able to account for the vulnerable requires us to do so through their lens and their way of seeing the world.

The potential for accounting to provide visibility of, and for, the vulnerable can be exemplified by the BBC being required to account for the pay of their top earners.Footnote9 Upon the production of a report of the previously unaccounted for levels of pay, the China editor Carrie Gracie resigned her position due to not being paid an equitable amount in comparison to her male counterparts. Here, Carrie Gracie can be seen to be vulnerable in the sense that she had the unfreedom of not being able to earn as much as her male colleagues; or, in other words, she had poorer economic opportunities. This is the type of ‘vulnerable’ people not covered in various categorical lists, such as those provided by the SDGs. Yet it is clearly one where accounting can assist, through providing visibility over what, up until then, was an unknown issue. Arguably, not only was Carrie Gracie being paid less, she should have been paid more, as the China editor role is more technically difficult and complex than the roles of some of her male counterparts. Being the China editor requires learning a difficult language, and the amount of relevant news to be covered constitutes a lot more. This exemplifies why it is equity, which focuses on the substantive freedoms of the individual, that should be of interest.

The Carrie Gracie example also highlights two more relevant issues. The first is that it illustrates how those who are considered to be wealthy and powerful are not immune from having their substantive freedoms restricted. It is well documented that the accounting profession is often vulnerable to losing their employment for a number of reasons including financial crises, bankruptcy of their organisation and downsizing (see for example Hopwood Citation2009, Sweeney and Quirin Citation2009). For example, a large number of individuals who had previously worked in the accounting profession (along with other professionals) ended up homeless in a relatively short space of time after the 2008–09 financial crisis. This resonates with the saying that we are all two pay cheques away from homelessness and suggests further areas for research within the remit of accounting for the vulnerable.

The second issue that the Carrie Gracie example raises is, while it is not right or proper that people are paid inequitably based on their gender, or any other such factor, we need to ask the question of whose vulnerability should be prioritised. This prioritising could be done in terms of the ‘capabilities’ of these people to lead the kind of lives they value. People, like Carrie Gracie, who are earning a reasonable amount of money may arguably be lower priority than, for example, those living on less than the UN standard of extreme poverty. That is, those living on less than US$1.25 per day would be considered to be more vulnerable and, thereby, warrant a high level of priority.

This suggests that more research is needed to ascertain who to prioritise as the most vulnerable. With this in mind, in the penultimate section, initial findings from the ongoing research project on accounting for the vulernable will be presented, which focuses on homelessness. This is because it is easy to argue that these people are among the vulnerable whom should be prioritised. For instance, access to housing is covered by article 25.1 of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This places an obligation on member states, to the homeless. This is further enshrined within SDG 11, Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable (United Nations Citation2015), where section 11.1 aims to, by 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing, as well as the upgrading of existing slums. A need for a focus on homelessness is also compounded by the rise of extreme poverty in the developed world (for example see Alston Citation2018), which has resulted in increased levels of people living without secure or stable access to housing. The next section turns to examining why the accounting profession should consider this as an area to undertake their public interest role.

4. Why should it matter to the accounting profession?

This section examines why the accounting profession should care about the vulnerable. Its starting point is to acknowledge that debate over the public interest role of the accounting profession, is far from resolved (Dellaportas and Davenport Citation2008, Killian and O’Regan Citation2020, Spencer Citation2020). When analysing the different perspective taken within this debate, a point of agreement seems to be that we all are, in one form or another, striving to create a better world (Glasser Citation2019). This is not surprising given that evidence supports that the more equitable a society is, the better the outcomes are for everyone, rich and poor alike, across a raft of different factors including life expectancy, literacy, infant mortality, crime rates and rates of mental illness (Stiglitz Citation2012, Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010). Nevertheless, as discussed above, the best current evidence suggests that our societies are becoming less equitable (Stiglitz Citation2015). As noted in the previous section, the accounting profession is implicated, particularly if the organisations they are employed by or the work they do is responsible for creating the unfreedoms that are causing this growing inequity. Further, accounting is also implicated in that it may keep invisible some of the inequities associated with organisations (Jollands Citation2016, Rahaman et al. Citation2004, Spencer Citation2020, Wällstedt Citation2020). This raises the question of how to reconcile tensions (Schweiker Citation1993) that may arise between accounting’s traditional focus on financial values and the values which underpin an accountant’s public interest role. Spencer (Citation2020, pp. 1–2) provides a statement that gives some guidance in this respect:

Around the rotunda of the original council chamber of ICAEW four virtues that our founding members considered characterised the profession. They are: wisdom; prudence; truth; and justice. I think that a narrative (I admit this is mine and I am imposing it) can be constructed: measurement is the craft of the chartered accountant, but they don’t simply compile the numbers. They take this and provide insight (wisdom) and do that using their skillset, their tool kit of curiosity, critical thinking and an ethical code (prudence). Because of this a truth can be told and people can hold individuals, businesses and other organisations to account (justice).

This statement points towards the established notion that the claim that accounting makes to objectivity is utilised within efforts to sanitise and delineate decisions as economic even though in reality they are inherently political (Callon Citation2010, Jollands et al. Citation2018, Miller and O’Leary Citation1987, Quattrone Citation2017). In making the call for more research, this requires more depth to the examination of how accounting is implicated within organisational practices that obfuscate the consequences of these activities for the vulnerable. Likewise, this should include examination as to how, as was seen in the example of Carrie Gracie, accounting can be utilised to illuminate areas of organisational practice that are resulting in increasing inequity. The Carrie Gracie example also highlights that one such organisational practice that may need to be examined is how accounting is intertwined with HR procedures, with a specific focus on pay equity. While in the example of Carrie Gracie the account demonstrated the disparity between those at the BBC who were earnings the most, there is widespread evidence (Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019) that across most organisations those earning higher amounts have seen their salaries increase at faster rates than those who have not. Such disparities between the top and bottom earners is problematic if there is a desire to create more equitable societies (Piketty Citation2014, Stiglitz Citation2012, Citation2015, Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2015). However, the question remains as to how much action has resulted from these accounts (Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2015), as per the discussion of plastics in our oceans (above). While such an investigation may find that not much action has resulted, it should be recognised that, just as this pay inequity is a result of deliberative management decision making, providing greater pay equity can and has been achieved. For instance, Schumacher (Citation1979) provided the example of the Scott-Bader Corporation in the UK where there was a decision taken that the differential between the lowest and highest paid worker would be no more than seven times. While this is a historical example, there are increasing trends in alternative organisational forms, such as B Corps (Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019), that hold the promise of addressing such pay inequities. At the very least, research could examine what institutional barriers remain in place, such as HR selection criteria prioritising people with private or grammar school educations, which constrain the potential, and thereby capabilities, of people to gain access to working in the accounting profession. This should also include barriers to entering higher education courses (Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2015), with education being argued as a critical element to constructing more equitable societies (Piketty Citation2014).

Moving beyond a focus on organisations, an analysis of existing research (Stiglitz Citation2012, Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010) highlights that, at the country level, there are at least two potential ways in which to create more equitable societies. The first way, which is frequently seen in the Nordic countries (Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010), is using the mechanisms of the state, specifically the tax system, to create more equity. There is much that needs to be researched here, particularly in relation to the accounting profession’s role and influence within this system. For example, in terms of equity, comparing the outcomes for people who commit welfare crime to those that commit tax fraud, research (Marriott Citation2017, Marriott and Sim Citation2017, Citation2019) has shown that the former is more severely punished than the latter. This suggests that the rewards and punishments between the two are disproportionate. Moreover, there have been many high profile cases of large multi-national corporations avoiding and evading tax responsibilities, which would not be possible without the assistance of tax accountants.Footnote10 An example of criticism of the accounting profession in the UK is that there seems to be a ‘revolving door’ between HMRC (tax authority) and the big four accounting firms.Footnote11 While this may be justifiable, for example as being within what the law allows, this situation compounds the inequity within countries and at the very least requires much more extensive research.

The second way, which is seen in Japan (Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010), relates to how an economy is structured. Like all countries, Japan has its issues. However, due to their economy directly contributing to a more equitable society they see less of the undesirable outcomes associated with the more inequitable countries. For example, Japan has long average life expectancy, high levels of literacy, low infant mortality, and insignificant crime rates (Wilkinson and Pickett Citation2010). Equity is achieved through the way in which Japanese organisations are set up and operate. Specifically, organisations in Japan have objectives that are aimed at contributing to society and, through undertaking these objectives, they are rewarded by earning a reasonable, but not excessive, profit. This illustrates that in Japan the public interest role is understood in a different way by, and beyond, the accounting profession (Sawabe Citation2005). The next section turns to examining what knowledge already exists in the extant literature.

5. Traditional, social and environmental accounting

This section presents an overview of some of the existing research that relates to accounting for the vulnerable, in order to demonstrate that there exists a foundation on which to build the much needed new research. Given the extensive history involved, including more than forty years of social and environmental accounting research, a succinct approach is taken, rather than an exhaustive review. More extensive reviews are available elsewhere (see for example Skilling and Tregidga Citation2019, Tweedie and Hazelton Citation2019). A starting point with such literature is a critical examination of traditional accounting in relation to the vulnerable, and as a way of reinforcing that the accounting profession is implicated if the organisations they are employed by or the work they do is responsible for creating the unfreedoms that are causing this growing inequity.

Everyday life is rich with situations where accounting makes things visible but also hides other matters (Jollands Citation2016, Rahaman et al. Citation2004), including those relating to the vulnerable. This links back to the traditional remit of accounting and specifically the accounting entity concept that underpins it. The accounting entity concept is useful as it assists with the construction of what is to be accounted for. However, it also constructs what is not to be accounted for, namely the ‘externalities’ (Jollands et al. Citation2018, Unerman et al. Citation2018, Veldman Citation2019). Hence, many of the impacts caused by an organisation remain unaccounted for, or invisible, in the set of accounts it produces. This includes how an organisation has alleviated or contributed to the unfreedoms of the vulnerable. If one of the entities to be accounted for, alongside the organisation, was the vulnerable, then visibility over these impacts would be created. That is, if an organisation’s operations were analysed using a different values lens, as undertaken for example in shadow accounting (Dey Citation2003, Citation2007, Tregidga Citation2017), it may provide broader understandings of how the organisational activities impact on the most vulnerable.

An example of this is provided by the ongoing debate over minimum wage and the living wage (Skilling and Tregidga Citation2019). In many contexts, minimum wage is not sufficient to live upon. However, organisations need workers to be fit and well, in order for them to undertake their jobs effectively. Usually it is the government who steps in and pays benefits to these workers so they can live, and thereby be productive employees. This thus acts as an indirect subsidy to the organisation. However, such a subsidy does not appear in the organisation’s traditional accounts, for example as a wages expense (Skilling and Tregidga Citation2019), and therefore remains largely invisible. But, if the government starts to cut back on benefits, for example during times of austerity, then the people and the organisations they work for start to feel the impacts through such things as increased sick payments, loss in productivity and decreases in profitability. Hence, the invisible subsidies start indirectly to become more visible in the accounts.

This example aligns with the Nordic approach, where redistribution through the mechanisms of the state are utilised to address equity. It is interesting, with reference to the other way of gaining more equity, that in Japan it is seen as shameful for an organisation to make excessive profits (McMann and Nanni Citation1995, Sawabe Citation2005). This is because the prevailing understanding is that the excessive profits have been made through either charging the customer too much, thereby the value received is insufficient for the amount they have paid, or not paying employees enough, thereby not fully recognising the value they have added. Further, in Japan part of the social objectives of an organisation is to provide employees with an honourable income (McMann and Nanni Citation1995, Sawabe Citation2005).

This suggests that an area in need of further research is whether the accounting profession should look to provide visibility over the perceived requirements, and benefits derived from, an organisation paying the living wage. Any such creation of visibility would need to extend beyond the business-as-usual arguments (Skilling and Tregidga Citation2019), which seek to reinforce the idea that there are business needs to paying minimum wage, such as affordability, generation of significant social value and market optimisation. Skilling and Tregidga (Citation2019, p. 2051) argue that accountants ‘might look to measure and publish the extent to which low wages are effectively subsidised through collectively funded welfare programmes and in-work tax credits’. Such visibility is a necessary, though not sufficient, step towards organisations taking action on such issues.

Traditional accounting also provides the accounting profession with opportunity to contribute to wider debates relating to the most vulnerable. An example that demonstrates this is in relation to a seemingly objective account prepared by the United Nations for the number of vulnerable people lifted out of extreme poverty. This account aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Specifically the claim is that the MDGs have resulted in a ‘total of 687 million people [being] lifted out of poverty from 1991 to 2010 for all reporting countries (which contain 40% of the world’s population)’ (Selomane et al. Citation2015, p. 142). This calculation is based upon a poverty line of those living on less than US$1.25 per day, in 2005 monetary terms. The US$1.25 per day definition of poverty can be critiqued from a time-value of money perspective (Pogge and Sengupta Citation2015, Scott and Lucci Citation2015). This benchmark has been weakened over time, with the original threshold of US$1.00 per person per day in 1985 monetary terms, later becoming a lower amount of US$1.08 per person per day in 1993 monetary terms, and finally to the current US$1.25 per person per day in 2005 monetary terms (Pogge and Sengupta Citation2015). If this calculation was constructed differently then what is made visible would also change. It has been calculated that if the poverty line of US$3 per person per day in 2005 monetary terms were used then the number of people below this poverty line would have actually risen by close to 27 million people (Pogge and Sengupta Citation2015). This raises the further question of whether US$1.26 or US$1.95 is still liveable, equitable, or substantively different from US$1.25. This also demonstrates that ‘success’ is related to how we set targets, as they define what it means to succeed, with the example here being US$1.25 per person per day. Key here, and something that warrants additional research, is to question whether we are managing the issues or are we managing the measurements. Glasser (Citation2019) queries whether the measurements of the UN result in questioning the taken for granted assumptions, that underpin our current systems, enough to produce the required level of change to be of any real benefit to the most vulnerable.

Beyond traditional accounting, aspects of social and environmental accounting provide a natural base for further research related to accounting for the vulnerable. In particular reporting frameworks such as the GRI and Integrated Reporting are starting to address the wider impacts of the organisation through placing the social and environmental next to the financial. These frameworks are largely based on notions of triple bottom lines of people, planet and profit. While this may be an appealing model, there are a number of issues with it (Gray and Milne Citation2004, Milne Citation1996). This includes the way in which the triple bottom line is usually depicted as three overlapping circles, suggesting that there are trade-offs to be made, which are not feasible if we are serious about creating a sustainable and more equitable world (Ball and Milne Citation2005). In part, the issues relate to what is considered to be the accounting entity. The use of these reporting frameworks only results in the direct impacts of an organisation being accounted for, with what is considered to be externalities, the cost of which are carried by others, still remaining absent (Jollands Citation2016, Veldman Citation2019). It has been known from at least as far back as Wiseman (Citation1982) that there is little relationship between this type of reporting and the organisation’s performance in these areas. Rather these types of reports are known to be utilised for reputation management (Bebbington et al. Citation2008), the seeking of legitimacy (Deegan Citation2007), or a multitude of other reasons (Milne Citation2013, Milne and Gray Citation2013), none of which focus on the impacts it has on the most vulnerable.

Contrasting this, there is an increasing amount of social and environmental accounting research that focuses on broader accounts, beyond reporting, that can be seen to have links with accounting for the vulnerable. Specific examples include social housing (see for example Collier Citation2005, Manochin et al. Citation2008, Smyth Citation2012), social impact bonds (see for example Cooper et al Citation2016), urban development (see for example Xing et al. Citation2009), modern slavery (see for example Christ et al. Citation2019), accounting for extortion (see for example Neu Citation2019), refugees (see for example Agyemang Citation2016), microfinance (for example see Alawattage et al. Citation2019, Vik Citation2017), and the living wage debate (Skilling and Tregidga Citation2019).

Some of this research is looking at practices that may appear to be focused on ecological aspects of sustainable development, but also uncovers interesting features relating to societal aspects. For example Jollands et al.’s (Citation2019) examination of Forest Enterprise England’s (FEE) use of Natural Capital Accounting has provided some surprising results in this area. That is, FEE used Natural Capital Accounting to demonstrate the broader value, beyond economic values, which they provide to society. While their remit is to manage the public forest estate, and to undertake commercial activities to provide the necessary economic resources, this is not where they add the most value. Rather, the largest area of value is created through allowing people recreational access to the public forest estate, contributing a vast amount to social wellbeing.

Hence the research of Jollands et al. (Citation2019) exemplifies two further points. The first is that there is a need for research that examines the interrelation between ecological and social sustainability, especially with a focus on accounting for the vulnerable. This will include exploring how the increased unsustainable exploitation of the ecology is resulting in increased levels of those that can be defined as vulnerable. The converse of this could also be explored; that is, how the increased levels of vulnerable people are resulting in increasing levels of unsustainable resource extraction. This may include examining, as seen in Wiseman (Citation1982), how accounting is obfuscating (or not) these processes. The second point is that the increased research focus in this area is not surprising given the interesting practices that can be observed and the surprising findings that these provide.

Another example is provided by Panasonic’s 250 year plan.Footnote12 In 1932 Panasonic started using a 250 year plan, which aimed to assist in fulfilling their long term mission ‘to banish poverty, bring happiness to people’s lives, and to make the world into a paradise’. This plan remains a working tool used at Panasonic, with the aim of helping managers within the organisation understand that the decisions they make today have implications well into the future. While the managers of Panasonic must ensure that they are financially sustainable in the short-term, the plan is used to prompt the managers to think about, and balance the short-term with, the long term legacy of the organisation. These examples demonstrate that some organisations and some professionals do implement strategies that commit to serving the public. Hence, these examples demonstrate that future research has a base of extant research to draw from and many varied and interesting practices to focus on. The next section explores this in the context of how approaching a seemingly straight forward issue related to social sustainability is beset with complexity.

6. Counting the homeless

In this section we present some initial findings from two case studies to provide an illustration of the potential for research into accounting for the vulnerable. Specifically, the focus is on counting the homeless which, including the political dimensions, has been examined in other disciplines (for example see Marquardt Citation2016). It is an area that has been selected particularly because it might challenge the common assumption of what gets measured gets managed. As will be seen, this is not as straight forward as it might appear.

This part of the field work was approached with three particular exploratory questions in mind.Footnote13 The first asks if there is a lack of entrenched or accurate numbers of people that are homeless. The second investigates what are the trends in relation to homelessness, and what they can tell us. Finally, we explore whether it is better to have an ‘imperfect’ number to act upon, and thereby an imperfect understanding of the scale and scope of homelessness, rather than continuing the search for ‘perfect’ numbers in the belief (see for example Leuz Citation2018) that these are required to make the ‘correct’ decision over the actions to be taken.

The starting point to examining these questions was to find an accepted definition of homelessness, the rationale being that whenever you wish to count something the first step is to define the very thing you wish to count. However, there is no agreed definition of homelessness, with different governments, charities, and NGOs utilising their own specific versions (Evans et al. Citation2019). There are of course commonalities between these various definitions. Analysis within a report by the Government Statistical Service (Citation2019) in the UK demonstrated that there were substantive differences in the administrative data systems and the legal definitions used across the countries in the UK. As such, having one harmonised definition was not possible.

In relation to the first question of whether there is a lack of entrenched or accurate numbers of people that are homeless, there are currently no reliable measures. At best there are only estimates. There are, however, a large number of reports from a variety of sources that give various estimates of the number of homeless people. An example, from the UK is that it is not even accurately known how many people die each year who are rough sleepers. A recently released report (Office for National Statistics Citation2019) used the number of homeless people known to have died in England and Wales (including people sleeping rough or using emergency accommodation, at or around the time of death) to estimate the best approximation of the numbers of people who were actually homeless at the time of their death. These estimates mean that the numbers are ‘imperfect’, with numerous flaws being present, as is acknowledged within the report. The flaws include that an upper age limit was used, which would have meant that some homeless people would have been excluded. Also of note is that this represents only the second set of official figures for England and Wales that have been released. As such, and in relation to the second question, while we do have trends to look at, they are again based on estimates.

The above findings are surprising in that as rough sleepers are the most visible homeless people, though in reality they are the tip of the iceberg, there may be an expectation as to the ease with which they can be counted. The impossibility of ‘counting’ rough sleepers was seen in the Auckland case study, where, in late 2018, a ‘Point in Time’ count was undertaken (Housing First Auckland Citation2019). On one specific night a large number of volunteers went out into the streets to survey rough sleepers. However, there are known issues with the statistics presented within the report. For example, it only provides estimates for people who would normally be rough sleepers but who spent that specific night in a temporary shelter. Further, rough sleepers typically know the city better than anyone, and therefore if they do not wish to be found then they will not be found (Evans et al. Citation2019, Kiddey and Schofield Citation2011). As such, the point in time count was criticised for its many flaws. The people interviewed, as part of the Auckland case study, who work on the frontline of homelessness, confirmed that the statistics shown in this count are well below the actual numbers of rough sleepers. They also noted that having these imperfect numbers were still of benefit. In practical terms, the point in time count demonstrates the difficulties involved in getting a fuller understanding of the number of homeless people. For instance, beyond rough sleepers, how can homeless people that are less visible, such as those living in sheds, cars, and on other people’s sofas, be counted? This is complicated by there being no single definition, which could determine who is counted and who is not.

Before exploring the third question of the usefulness of imperfect numbers, some preliminary reflections from the first two questions is needed. For this, it is helpful to return to the long-established caution against the use of accounts, such as these counts of the homeless, being utilised to make people calculable and controllable (Bisman Citation2012, Miller and O’Leary Citation1987, Wällstedt Citation2020). This can be contrasted with the need to ensure that the accounting for and action taken in relation to the individual homeless person is one that addresses their specific unfreedoms and the expansion of their capabilities (Needham Citation2010). The need to treat such people as individuals is seen in the findings of Hodgetts et al. (Citation2012), who note that how much the experience of homelessness differs from the person’s historical living conditions will influence the type of assistance they require.

This acknowledgement that there is a need to understand homeless people at the individual level has resulted in projects such as The Empty Doorway by The Guardian,Footnote14 which aims to personify the statistics of rough sleepers who have died in the UK. One example from this project is Hamed Fahari Alamdari who had been living in his car before passing away in 2018. He had a degree in Quantum Physics and was once shortlisted for a job working with Stephen Hawking. However, homelessness was the final outcome of his post-traumatic stress disorder, caused by fighting in the Iran-Iraq war. His example raises the question of whether we are also losing value that homeless people may have otherwise contributed to society.

This means that when undertaking research in this area there is a need to balance understanding the drivers that are causing homelessness issues with ensuring that responses are targeted at the individual level. This is exemplified in the extensive, but reductionist focused, literature review provided by Evans et al. (Citation2019). Much of the research examined in their article, which primarily uses randomised controlled trial evaluations and quasi-experimental designs, suffers from the simplistic approach that, when relied upon alone, cannot address the complexities involved with such wicked problems. Much of this type of research at best treats the homeless as problematic and costly statistics which need to be managed (Merry Citation2016, Wällstedt Citation2020), with landlords and other actors, in contrast, being treated as (bounded) rational actors. To the credit of Evans et al. (Citation2019) they do acknowledge that for the homeless person it is an ‘uneven playing field’. Specifically they refer to the research of Desmond (Citation2012, Citation2016) to highlight, when people are being made homeless through eviction, that the relative economic power of the landlords, who can afford lawyers, versus the evictee, typically results in the former prevailing regardless of the merits of the specific case. However, much of this research effort comes to a conclusion or makes the assumption that homeless people are costly. As such, they are of importance not necessarily because it is the ethical thing to do, but rather because the financial implications makes them in need of being controlled (Miller and O’Leary Citation1987, Sandel Citation2013, Wällstedt Citation2020). There is a danger therefore that the initiatives put in place to address the issues surrounding homeless people are hijacked by dominant narratives, such as ‘efficiency’ and ‘value-for-money’, that end up having outcomes that are less than ideal for the individual (Lapsley Citation2009, Needham Citation2010).

One initiative that has great potential, but is also known to produce unintended consequences, is Housing First (HF). The HF model flips the way of dealing with homelessness, from treating the person’s other issues (e.g. addiction, employment) first to initially placing the person in subsidised private-market housing (Evans et al. Citation2019). While, if implemented appropriately, this can be a useful way of dealing with chronic homelessness, it however often becomes dominated by a focus on financial aspects, such as the savings it produces to other services (Evans and Masuda Citation2019, Hennigan Citation2017). The main focus of HF is on those homeless people who consume most resources, leaving others that are affected by homelessness, but who are not so costly, and the wider root-causes unresolved (Hennigan Citation2017). HF does not address the underlying drivers that are resulting in homelessness, such as the shortage of affordable housing and the effects of a highly marketised housing system (Evans and Masuda Citation2019, Sandel Citation2013). Thus while HF is fast becoming the preferred response to homelessness, Soederberg (Citation2017) has criticised such programmes as being co-opted by profit seeking organisations, who utilise them to crowd-out certain responses to housing shortages in favour of business-orientated ones that require minimum involvement of other agencies, including that of the state.

A final point in relation to the research overviewed by Evans et al. (Citation2019) concerns what has been put into place in terms of policy to address the issue of homelessness. As acknowledged by Evans et al (Citation2019, p. 40), the extant research does little to address the lived experiences of those individuals who experience policies in action. For example, research focuses on how to rehouse the homeless without discussing just as important and interrelated aspects, such as the quality of housing or the exploitativeness of so called slum-landlords that own much of the private-market housing where HF clients are placed (Evans and Masuda Citation2019, Hennigan Citation2017). Evans et al. (Citation2019) also discuss the statistical research on housing shelters, but not the lived experiences or the long term effects on those placed there.

In relation to understanding the lived experiences, within the course of undertaking the case studies mentioned within this section, many homeless people stated that they feel safer sleeping rough on the streets, rather than in many of the homeless shelters. In particular, those interviewed raised concerns with gangs operating in shelters, the threat of violence and possibility of trafficking, or the consequences of sheltering with other less stable people. All of this, it is argued, demonstrates further the wicked problem that accounting for the vulnerable relates to and the need, therefore, for pluralistic approaches in its research.