Abstract

Introduction

The aim of study was to assess the impact of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol and minimally invasive approaches on short-term outcomes in rectal surgery.

Patients and methods

A consecutive series of patients that underwent open or minimally invasive rectal resections in a single institution between January 2015 and April 2020 were included in the study. An ERAS program was introduced in April 2016. The study cohort was divided into three groups: open surgery without ERAS, open surgery with ERAS, and minimally invasive surgery with ERAS. Outcome measures compared were recovery parameters, surgical stress parameters, 30-day morbidity and mortality, oncological radicality and length of hospital stay.

Results

A total of 202 patients were included: 43 in the open non-ERAS group, 92 in the open ERAS group and 67 in the minimally invasive ERAS group. All recovery parameters apart from postoperative nausea and vomiting were significantly improved in both ERAS groups. Surgical stress parameters, prolonged postoperative ileus, and hospital stay were significantly reduced in the minimally invasive ERAS group. The overall 30-day morbidity and mortality and oncological radicality did not significantly differ among the three groups.

Conclusions

Minimally invasive approaches and enhanced recovery care in rectal surgery improve short-term outcomes. Their combination leads to an improvement in recovery parameters and a reduction of prolonged postoperative ileus and hospital stay.

Introduction

Rectal cancer is the eight most common cancer, with the highest rates occurring in Eastern Europe [Citation1]. It remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Survival after rectal surgery has dramatically improved in the last few decades following the implementation of total mesorectal excision and chemoradiotherapy [Citation2]. Recovery parameters have been improved and length of hospital stay and complication rates have been reduced following the implementation of minimally invasive procedures and enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols [Citation3,Citation4].

As technically demanding procedures with steep learning curves, implementation of minimally invasive approaches in rectal surgery has been much slower than in other surgical fields. Nevertheless, there is an increasing amount of evidence, including randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses, showing that when compared with an open approach, minimally invasive rectal surgery is associated with faster recovery times, less blood loss, and shorter hospital stays, while providing equivalent oncological outcomes [Citation5,Citation6]. In the current ERAS guidelines, the use of minimally invasive techniques is strongly recommended [Citation7]. Laparoscopic surgery in the Czech Republic is well established and is being performed with increasing frequency. According to a national questionnaire in 2006, more than 70% of cholecystectomies and 40% of appendectomies were performed laparoscopically [Citation8]. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery is performed much less frequency, being used in 58% of surgery departments. Similarly, ERAS protocols have not yet become widely implemented, with a recent report showing that the majority of Czech surgery departments do not comply with ERAS protocols and that minimally invasive approaches are used in 10% of colorectal procedures [Citation9]. Robotic colorectal surgery was introduced in the Czech Republic in 2005 and over a 15 year period over 1059 robotic rectal resections have been performed in a total of 11 robotic centres [Citation10].

In our department, enhanced recovery care has been implemented in April 2016, laparoscopic rectal surgery in May 2016 and robotic rectal surgery in July 2018. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of an ERAS program and minimally invasive approaches on the short-term outcomes in patients undergoing rectal resections.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

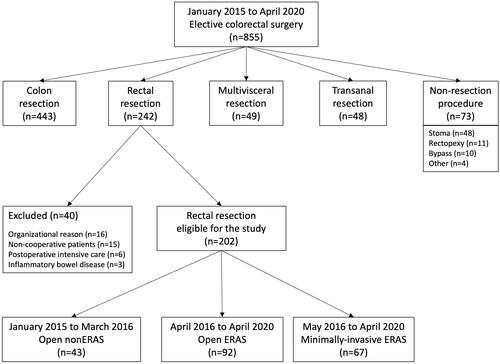

Patients undergoing elective colorectal procedure at the department of surgery of the Motol University Hospital in Prague between January 2015 and April 2020 were assessed for eligibility to be included in the study. Patients who underwent colon resection, multivisceral resection, transanal resection, or non-resection procedure were excluded. A total of 242 patients who underwent rectal resection were identified. Of these, 40 patients were further excluded due to one of the following reasons: organizational problem (i.e. ERAS staff not available, n = 16), non-cooperative patients (i.e. severe dementia, mental retardation, n = 15), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 3), and postoperative intensive care (i.e. major intraoperative complications necessitating postoperative care in the department of anaesthesiology and resuscitation, n = 6).

A total of 202 patients were included in the study. These consecutive patients were categorised into three groups according to the surgical approach and perioperative management. The first group of patients underwent open rectal resection with standard care between January 2015 and March 2016, the second group underwent open rectal resection with ERAS care between April 2016 and April 2020, and the third group underwent minimally invasive rectal resection with ERAS care between May 2016 and April 2020 (). The study was approved by the institutional ethical board (reference no. EK-760/18).

Data collection

Data were collected from a prospectively managed database of all patients undergoing elective colorectal procedure at the department of surgery of the Motol University Hospital in Prague between January 2015 and April 2020. The following data were extracted and analysed in each group: patient characteristics (age, gender, ASA score, body mass index, malnutrition, corticosteroids, TNM stage, and neoadjuvant therapy), surgical details (procedure type, stoma creation, procedure time and blood loss), recovery parameters (presence of postoperative nausea and vomiting, successful mobilisation on the first postoperative day, feeding tolerance, mean intravenous fluid administration on the day of the surgery, use of parenteral nutrition), surgical stress parameters (white blood cell counts and C-reactive protein levels on the first three postoperative days), 30-day morbidity and mortality ( according to Clavien–Dindo classification, surgical site infection, anastomotic leak, prolonged postoperative ileus, bleeding, urological, cardiac and respiratory complications), oncological radicality (number of lymph nodes harvested, resection margin status, and quality of the mesorectal excision), length of hospital stay, and readmission within the first 30 days after discharge. Malnutrition was defined if two out of the three following conditions were fulfilled: (1) BMI under 20 in patients younger than 70 years of age or BMI under 17 in patients older than 70 years, (2) total protein lower than 55 g/L and (3) albumin lower than 30 g/L. Prolonged postoperative ileus was diagnosed if any two of the following items were met on or after the third postoperative day: nausea or vomiting, intolerance of oral diet over 24 hours, absence of flatus over 24 hours, distension, radiological evidence of ileus.

ERAS protocol

The ERAS protocol consisted of 16 items. A list of all these items with the adherence is shown in . A more detailed description of our ERAS protocol can be found in our previous study [Citation11]. A brief description of the main items is given here. Preoperative counselling and nutritional screening were provided. Patients were given carbohydrate rich drinks two hours before the surgery. All patients apart from those with stenotic tumours received mechanical bowel preparation. Intraoperatively patients were actively heated by a convective air warming system and by warming intravenous fluids. Intravenous fluids were administered according to the principles of goal-directed fluid therapy. Epidural catheters were used only in open procedures. Early feeding and early mobilization after surgery were implemented. We aimed for patients to return to a full solid diet by the fourth postoperative day. Multimodal opioid-sparing analgesia consisted of a combination of paracetamol with metamizole and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; this item was considered fulfilled when patients received no more than one dose of opioids per day.

Table 1. Adherence to the ERAS protocol.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the program R (R 4.0.0 GUI 1.71 Catalina build (7827), R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016). Fisher’s test was used to compare categorical variables and linear regression models were used for continuous variables. p Values of less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

A total of 202 patients were included in the study. Forty-three patients underwent open procedures with standard care, 92 patients underwent open procedures with ERAS care, and 67 patients underwent minimally invasive procedures with ERAS care. A total of 47 procedures were performed robotically and 20 procedures were performed laparoscopically.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in . There were no significant differences in age, gender, ASA score, BMI, corticosteroid therapy, TNM stage, or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, but there was a significant difference in malnutrition. Malnutrition was more frequent in patients who underwent open procedures with standard care compared with patients who underwent open or minimally invasive procedures with ERAS care (20.9% versus 2.2% versus 1.5%, respectively; p = <.001).

Table 2. Patient characteristics.

Surgical details

Surgical details are shown in . Minimally invasive procedures were significantly longer than open procedures and had a smaller blood loss (199 min versus 133 min, 74 mL versus 261 mL, respectively; p= <.001). The types of procedure performed and the stoma rate were not different among the three groups.

Table 3. Surgical details.

ERAS protocol

The average overall adherence to the ERAS protocol was 81.8%. Full adherence was achieved in antithrombotic and antibiotic prophylaxis and active warming. The items with the lowest adherences were early removal of Foley catheters (12.6%), early removal of abdominal drains (4.4%), and goal-directed fluid therapy (67.3%). Adherence of over 75% was achieved in all other items ().

Outcome measures

Outcome measures are reported in . All recovery parameters apart from postoperative nausea and vomiting were significantly improved in patients treated by ERAS care. The combination of minimally invasive approach and ERAS care led to a significant reduction of surgical stress parameters, prolonged postoperative ileus and length of hospital stay. Patients who underwent minimally invasive procedures with ERAS care had significantly lower white blood cell counts on the first and third postoperative day and C-reactive protein levels on the first three postoperative days than patients who underwent open procedures with standard care. The incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus was significantly reduced from 20.9% in the open non-ERAS group to 3.0% in the minimally invasive ERAS group (p<0.01) and the average length of hospital stay shortened from 15.2 to 11.4 d (p<0.01). The rates of other complications, oncological radicality and readmission rates did not differ among the three groups.

Table 4. Outcome measures.

Discussion

In this single centre retrospective study we evaluated our experience with rectal surgery. We compared three groups of patients who underwent rectal resections: open resection with standard care, open resection with ERAS care and minimally invasive resection with ERAS care. We showed that ERAS care and minimally invasive surgery improved postoperative outcomes.

The patient characteristics were similar between the three groups, apart from malnutrition, which was lower in patients with ERAS care. This was due to the implementation of nutritional screening as part of the ERAS protocol and subsequent nutritional interventions. Minimally invasive procedures were associated with a longer procedure length and less blood loss. Recovery parameters, apart from postoperative nausea and vomiting, were improved in all patients who had ERAS care. Postoperative nausea and vomiting were reduced in the two ERAS groups, although this did not reach statistical significance, probably due to the cohort size. The surgical stress parameters, white blood cell counts and C-reactive protein levels, were reduced in the minimally invasive group. These patients also had a reduced incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus. Hospital stay was the shortest in patients undergoing minimally invasive procedures and readmission rates did not significantly differ in the three patient groups.

Both minimally invasive surgery and ERAS protocols have been shown to reduce the inflammatory response to surgery. In our patients, C-reactive protein values and white blood cell counts were lower in patients who underwent minimally invasive procedures applied within an ERAS protocol, but the effect of ERAS alone without a minimally invasive approach did not result in lower inflammatory parameters. A systematic review on this subject concluded that laparoscopic surgery was associated in a reduction of the inflammatory response to surgery, but no strong conclusions could be made about the role of other ERAS items in reducing the inflammatory response to surgery as studies investigating them were lacking [Citation12]. We noted a successive decline in white blood cell count over the first three postoperative days in all three patient groups. The C-reactive protein level on the other hand rose on the second day and then declined on the third day. Deviations in these dynamics can help to promptly detect postoperative complications such as anastomotic leak [Citation13].

Length of stay was significantly shorter in patients who had the combination of ERAS care and minimally invasive surgery. The median length of hospital stay for these patients was 9 days compared to 13 days for patients who underwent open surgery with standard care. Nonetheless, in comparison to other studies in the literature this length of hospital stay is relatively long. This is partially due to large proportion of abdominoperineal resections, protective ileostomies, and terminal colostomies performed: abdominoperineal resections constituted 21%, protective ileostomies 25%, and terminal colostomies 24% of the patients undergoing minimally invasive procedures. Abdominoperineal resection belongs to the most invasive of rectal procedures and has a longer reconvalescence period than other rectal procedures. The perineal wound is prone to healing complications, particularly in patients after neoadjuvant treatment [Citation14]. In some centres, abdominoperineal resections are excluded from ERAS protocols [Citation15]. Patients with stomas have to be educated by a stoma care nurse before discharge on how to take care of their stomas and patients with ileostomies are prone to electrolyte abnormalities for a variable period of time in the immediate postoperative period and can only be discharged after this has normalised. In contrast to studies with much shorter lengths of hospital stay our readmission rate was low and did not differ between the three patient groups [Citation16–18]. This is a benefit of the longer hospitalisation rate; complications that would otherwise require re-hospitalisation happened during the primary hospital stay.

Although the overall 30-day morbidity and mortality were not reduced by either ERAS with or without a minimally invasive approach, the incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus was reduced in patients who underwent minimally invasive rectal surgery. Prolonged postoperative ileus is one of the most common complications of colorectal surgery, affecting an estimated 10-15% of all patients [Citation19]. Several factors are known to be protective for prolonged postoperative ileus, among them are laparoscopic approach, epidural analgesia, opioid-sparing analgesia and early oral feeding [Citation20–22]. All these are ERAS protocol items that were implemented in our study and contributed to the reduction when comparing the open ERAS group with the open non-ERAS group and a further reduction was seen in the minimally invasive ERAS group, in whom the rate of postoperative ileus was the lowest(3.0%).

Conclusions

Minimally invasive approaches in rectal surgery applied within enhanced recovery care improve the already outstanding results of each of the two taken individually. The combination of these two modalities leads to an improvement in recovery parameters and a reduction of prolonged postoperative ileus and hospital stay. Therefore, we strongly believe that minimally invasive approach must be considered as one of the core items of enhanced recovery care in rectal surgery.

Limitations of the study

One of the potential limitations of the study is the selection of procedures for minimally invasive surgery. When we began with laparoscopic and robotic surgery we preferentially selected patients with smaller tumours, with normal BMIs, without a history of major abdominal surgery and patient who had not received neoadjuvant therapy. As we became more experienced with these procedures, we began to indicate more complicated cases and currently with the exception of multi-visceral resections, which were all excluded from this analysis, all rectal resections are performed laparoscopically or robotically. Although it did not reach statistical significance there were noticeable differences in tumour stage and neoadjuvant therapy between the groups.

Further limitations include the non-randomised study design and relatively small study size. There was also a time period difference in the patient groups as non-ERAS open procedures took place prior to the ERAS groups. Another limitation is the learning curves associated with the introduction of both the minimally invasive approaches (laparoscopic and robotic) and enhanced recovery care implementation.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no commercial or other associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the manuscript.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Brouwer NPM, Bos ACRK, Lemmens VEPP, et al. An overview of 25 years of incidence, treatment and outcome of colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(11):2758–2766.

- Khreiss W, Huebner M, Cima RR, et al. Improving conventional recovery with enhanced recovery in minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(5):557–563.

- Huibers CJA, de Roos MAJ, Ong KH. The effect of the introduction of the ERAS protocol in laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(6):751–757.

- Tong G, Zhang G, Liu J, et al. A Meta-analysis of short-term outcome of laparoscopic surgery versus conventional open surgery on colorectal carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(48):e8957.

- Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, et al. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1324–1332.

- Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations: 2018. World J Surg. 2019;43(3):659–695.

- Martínek L, Dostalík J, Gunka I. Minimally invasive surgery in the Czech Republic. Rozhl Chir. 2008;87(11):563–566.

- Ryska O, Serclová Z, Antoš F. Compliance with the procedures of modern perioperative care (enhanced recovery after surgery) at surgery departments in the Czech Republic - results of a national survey. Rozhl Chir. 2013;92(8):435–442.

- Rejholec J. 15 years of robotic surgery in Czech republic. Presented at: healthcare 4.0; May 23; Prague. 2019. Available from: http://www.top-expo.cz/domain/top-expo/files/smart-city/smart-city-2019/zdravotnictvi-4.0/prezentace/rejholec_jan.pdf

- Kocián P, Whitley A, Přikryl P, et al. Enhanced recovery after colorectal surgery: the clinical and economic benefit in elderly patients. Eur Surg. 2019;51(4):183–188.

- Watt DG, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: which components, if any, impact on the systemic inflammatory response following colorectal surgery: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(36):e1286.

- Almeida AB, Faria G, Moreira H, et al. Elevated serum C-reactive protein as a predictive factor for anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Int J Surg. 2012;10(2):87–91.

- Colov EP, Klein M, Gögenur I. Wound complications and perineal pain after extralevator versus standard abdominoperineal excision: a nationwide study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(9):813–821.

- Rouanet P, Mermoud A, Jarlier M, et al. Combined robotic approach and enhanced recovery after surgery pathway for optimization of costs in patients undergoing proctectomy. BJS Open. 2020;4(3):516–523.

- Asklid D, Gerjy R, Hjern F, et al. Robotic vs. laparoscopic rectal tumour surgery: a cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2018;21+:191–199.

- Law WL, Foo DCC. Comparison of short-term and oncologic outcomes of robotic and laparoscopic resection for mid- and distal rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(7):2798–2807.

- Trastulli S, Farinella E, Cirocchi R, et al. Robotic resection compared with laparoscopic rectal resection for cancer: systematic review and Meta-analysis of short-term outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(4):e134–e156.

- Quiroga-Centeno AC, Jerez-Torra KA, Martin-Mojica PA, et al. Risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2020;44(5):1612–1626.

- Grass F, Slieker J, Jurt J, et al. Postoperative ileus in an enhanced recovery pathway-a retrospective cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(5):675–681.

- Guay J, Nishimori M, Kopp S. Epidural local anaesthetics versus opioid-based analgesic regimens for postoperative gastrointestinal paralysis, vomiting and pain after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(7):CD001893.

- Ng WQ, Neill J. Evidence for early oral feeding of patients after elective open colorectal surgery: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(6):696–709.