Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) may be associated with chronic pain, seroma formation, bulging and failure to restore abdominal wall function. These outcomes are risk factors for hernia recurrence and poor quality of life (QoL). Our study evaluates whether robotic-assisted ventral hernia repair (rVHR) diminishes these complications compared to LVHR with primary closure of the defect (hybrid).

Methods

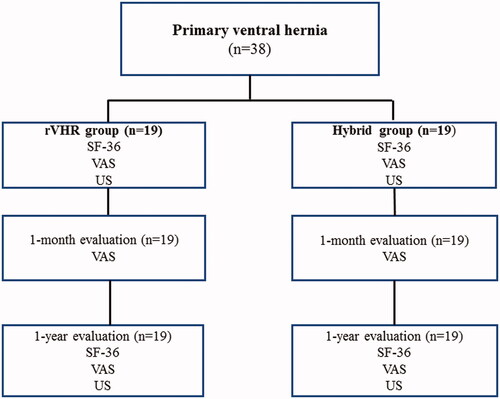

Thirty-eight consecutive patients undergoing incisional ventral hernia operation with fascial defect size from 3 to 6 cm were recruited between November 2019 and October 2020. Nineteen patients underwent rVHR and nineteen underwent hybrid operation. The main outcome measure was postoperative pain, evaluated with a visual analogue scale (VAS: 0–10) at 1-month and at 1-year. Hernia recurrence was evaluated with ultrasound examination and QoL using the generic SF-36 short form questionnaire.

Results

At the 1-month control visit, VAS scores were significantly lower in the rVHR group; 2.5 in the hybrid group and 0.3 in the rVHR group (p < 0.001). At the 1-year control, the difference in VAS scores was still significant, 2.8 vs 0.1 (p = 0.023). There was one hernia recurrence in the hybrid group (p = 0.331). QoL did not differ significantly between the study groups when compared to preoperative physical status at 1-year follow-up (p = 0.121). However, emotional status (p = 0.049) and social functioning (p = 0.039) improved significantly in the rVHR group.

Conclusions

Robotic-assisted ventral hernia repair (rVHR) was less painful compared to hybrid repair at 1-month and at 1-year follow-up. In addition, improvement in social functioning status was reported with rVHR.

Trial Registration ID

5200658.

Introduction

Repair of abdominal wall hernia is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures [Citation1]. Ventral hernias can be categorized as spontaneous such as epigastric, umbilical or Spigelian or acquired hernias [Citation2]. About 5% of the general population is born with or develops a primary hernia [Citation3]. Incisional or secondary hernias develop in up to 30% of patients undergoing abdominal operations [Citation4]. Hernia types according to location are categorized using the European Hernia Society classification [Citation5]. Operations of ventral hernia are associated with numerous complications including pain, seroma, infection, eventration, recurrence, poor cosmesis or poor function of the abdominal wall [Citation6]. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) usually implies intraperitoneal placement of a prosthetic mesh without closure of the fascial defect. It is often technically difficult to close the fascial defect, particularly for hernias wider than 10 cm [Citation7,Citation8]. In some cases, the mesh bulges through the defect and produces a sensation of hernia recurrence. Primary closure of the defect (hybrid) performed in a minimally invasive fashion is good for recreation of the abdominal wall, and to prevent recurrence or bulging [Citation8].

Chronic pain, recurrence and quality of life (QoL) are important outcome variables for ventral hernia repair. Chronic pain may be of significant concern in many patients, leading to prolonged consumption of analgesics and limitation of daily activities. Failure to close the fascial defect is associated with increased seroma formation, recurrence and low QoL [Citation9]. Acute and chronic pain is reported to be higher after LVHR without primary closure of the defect [Citation10]. The incidence of chronic pain after LVHR ranges between 1.3% and 14.7% [Citation10]. After hybrid operation, the incidence is less, between 5% and 7% [Citation11]. It appears that closing the hernia defect lowers the risk for chronic pain [Citation12]. Therefore, it is a growing global tendency among laparoscopic surgeons to close the primary defect [Citation12,Citation13]. However, laparoscopic intracorporeal closing sutures for defect closure are challenging, and sutures, tacks or glue for mesh fixation have been associated with post-operative pain [Citation14]. Robotic-assisted operation has been described as a new modality in this field that can facilitate intracorporeal closure of the defect and a better abdominal wall function [Citation15]. Robotic-assisted ventral hernia repair (rVHR) provides several benefits over the hybrid assisted approach, because it may afford benefits of the laparoscopic approach while facilitating a more robust and less painful repair. However, long-term results of the rVHR compared to other techniques are limited [Citation9,Citation16,Citation17]. The aim of this study was to compare 1-year outcomes of patients who underwent rVHR or hybrid operation.

Material and methods

Patients accepted to ventral hernia surgery at Kuopio University Hospital were recruited into this ongoing prospective study. From November 2019 to October 2020, 38 adult consecutive patients (22–73 years) undergoing elective primary incisional ventral hernia in a day-case operation with fascial defect size from 3 to 6 cm were recruited into the study. A preoperative ultrasound examination was performed. All operations were performed by two surgeons with good expertise in laparoscopic and robotic assisted surgery. The flow chart is shown in . Two surgeons recruited eligible patients consecutively from the waiting list, and written informed consent was obtained before the operation. Patients cannot be identified via the paper and they have been fully anonymized. Nineteen consecutive patients underwent rVHR and nineteen consecutive patients underwent hybrid operation. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District (Trial Registration ID 5200658). All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Perioperative details of patient demographics, comorbidities and surgical histories were collected. Preoperative and postoperative pain was evaluated during mobilization by the same two surgeons on a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 10, during the postoperative hospital stay and after 1-week, 1-month and 1-year. Zero in VAS meant no pain and number ten was the highest possible pain. A follow-up ultrasound examination was performed on demand to show possible seromas or recurrent hernias. Postoperative complications were graded according to the Clavien–Dindo scale [Citation18].

The QoL was measured using the generic SF-36 short form questionnaire [Citation19]. The SF-36 measures nine scale scores: physical functioning, role functioning (physical), role functioning (emotional), bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional well-being and changes in health. On all scales, higher scores represent a better function or outcome. The SF-36 was completed by the patients preoperatively and after 1-year follow-up. Patients’ satisfaction with the cosmetic outcome was measured using a scale from 0 to 1 (0 = no and 1 = yes) 1-year after surgery.

The main outcome measure of this study was postoperative pain (VAS) at 1-month and at 1-year after surgery. The secondary measures were QoL and hernia recurrence at 1-year after surgery.

Surgical technique

Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with primary closure of the defect (hybrid)

In the hybrid group the 2 trocars (10 mm each) were placed laterally. Laparoscopy was performed first to see the size and the number of the defects. Adhesiolysis was completed when needed and reduction in hernia contents in the abdominal cavity was performed. The defect size was measured with a tape. A standard laparoscopic intraperitoneal polypropylene on lay lightweight mesh (Ti-Mesh®, pfm medical ag, Germany) was fixed using a single crown of absorbable tacks every two centimeters. The tacker fixation device was a SecureStrap™ absorbable fixation device (Ethicon 360, Johnson & Johnson, USA). Appropriate overlap of at least 5 cm in all directions was measured. After the intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair, a small, average 3 cm minilaparotomy incision was made. The hernia sack was resected, and the fascial defect was closed with a slowly absorbing monofilament suture (0–0 Maxon® or PDS®). One stitch was taken to the mesh to avoid displacement and inward bulging. If a patient had multiple hernia defects, all defects were closed in this way.

Robotic retromuscular ventral hernia repair

In the robotic-assisted ventral hernia repair the Da Vinci Xi Surgical System® (Intuitive Surgical Inc, Sunnivale, CA, USA) was used. Intraperitoneal access was obtained in a similar fashion as in the hybrid group. A basic principle for docking the robot was utilized. The robot, the hernia and the camera should all be in a straight line. This approach requires the use of 3 ports, one for the camera (8 mm) and two for the robotic arms (8 mm each). Robotic ports were placed as laterally as possible in order to allow the surgeon to close the defect and fix the mesh with a 5 cm overlap. The robot was docked at the left side of the patient. Once docked, any necessary adhesiolysis and reduction of hernia contents into the abdominal cavity was performed. The defect was measured in a similar fashion as in the hybrid group. Retromuscular dissection was started by incising the posterior rectus sheath along the entire length of the hernia defect, separating the rectus muscle from the posterior fascia, and extending at least 5 cm above and below the hernia in order to allow adequate mesh overlap. Dissection was carried out across the midline, including excision of the hernia sac and re-entering the contralateral rectus sheath. The hernia defect was closed anteriorly with a running, non-absorbable suture (0-0 V-Lock®, Medtronic). This space was measured, and uncoated self-adherent polyester heavyweight mesh (Progrip®, Medtronic, France) was cut to size and placed against the anterior abdominal wall. Finally, the posterior sheath was closed along the initial incision using a running, absorbable suture (3-0 V-Lock 90®, Medtronic).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software for Windows (version 27.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data are given as means ± SD and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Independent samples t-test and Mann–Whitney U-non-parametric tests were used to assess the significance of changes in response to surgery (). Independent samples t-test and Mann–Whitney U-tests were in line with each other.

Table 1. The characteristics of the study groups.

Table 2. One-year surgical outcomes following hybrid and rVHR.

Table 3. Pre- and post-operative SF-36 scores comparing results in hybrid and rVHR group.

Results

Clinical characteristics of 38 individuals participating in this study are shown in . The hybrid and rVHR groups were well matched, because the groups were similar in terms of demographics, comorbidities, hernia type, and surgical histories. There was no significant difference in gender, hernia type, hernia size, comorbidities, body mass index (BMI) or prior surgical histories between the two study groups. Hernia defect size (p = 0.834, difference OD = −0.134, 95% CI −1.423 to 1.155) and number of hernias (p = 0.689, difference OD = −0.049, 95% CI −0.296 to 0.198) were similar in both groups (). However, rVHR required a longer operation time (p < 0.001, difference OD = 92.268, 95% CI 70.893–113.643), (). The need for analgesics was similar in both groups during the first 24 h after surgery.

The main finding was that the rVHR group reported less pain at 1-month and at 1-year after the operation compared to the hybrid group. At the 1-month control visit, we found a significant difference in VAS. The mean pain scores were lower in the rVHR group (0.3) than in the hybrid group (2.5, p < 0.001, difference OD = −2.196, 95% CI −3.404 to −0.989). At the 1-year control, VAS was 0.1 vs 2.8 (p = 0.023, difference OD= −2.667, 95% CI −4.907 to −0.426) in the rVHR group vs the hybrid group, respectively (). The clinical outcome at the 1-year follow-up is shown in . There was one seroma formation, mesh bulging (p = 0.331, difference OD = −0.100, 95% CI −0.310 to 0.110) and hernia recurrence (p = 0.331, difference OD= −0.100, 95% CI −0.310 to 0.110) in the hybrid group, which did not give a statistically significant difference. All of these outcomes were in the same patient. Re-hernioplasty was performed because of the pain. The QoL questionnaires were gathered at two points: preoperatively, and 1-year after the operation. Subjective improvement in overall patient satisfaction was reported equally in both groups (). All nine SF-36 scale scores favoured the rVHR, but without statistical significance. However, emotional status (p = 0.049, difference OD = −40.0, 95% CI −79.68 to −0.32) and social functioning (p = 0.039, difference OD= 18.75, 95% CI 1.16 to 36.34) improved significantly in the rVHR group ().

Discussion

The rate of incisional hernias remains high, despite recent advances in technology and surgical techniques. The open approach continues to be widely performed for ventral hernia repair, whereas the minimally invasive hybrid and robotic-assisted operations have been described as a new modality in this field [Citation20]. Laparoscopic suturation is not a commonly used technique among Finnish surgeons in the case of extensive hernia defects and there was some concern about the potential impact of a learning curve. Therefore, the hybrid technique was chosen to assure familiar and proper defect closure. Robotic assisted hernia repair is also not a commonly used technique among Finnish surgeons, since there are very few Da Vinci Xi Surgical System® robots in Finland. Therefore, forty robotic assisted ventral hernia operations were operated by two surgeons before this study. Our aim was to explore whether the robotic-assisted technique decreases postoperative pain and hernia recurrences and increases the QoL compared to hybrid repair.

First, we found that at 1-month after surgery, patients operated with the rVHR technique suffered significantly less from pain than patients who were operated with the hybrid technique. Second, we found that this outcome was also significant at 1-year follow-up in favour of the rVHR group. Third, we found that emotional status and social functioning improved significantly in the rVHR group. Subjective improvement in overall patient satisfaction was reported equally in both groups.

In our study, the hernia size was similar in both groups. Despite more extensive dissection with 5 cm overlap involved in rVHR group, patients had significantly less pain at 1-month and at 1-year. This is in line with the study of Chelala et al., in which, after hybrid operation, the incidence of pain was as high as 5% and 7% [Citation11] and after rVHR less than 3% [Citation21]. By contrast, Petro et al. found no difference in postoperative pain [Citation22]. Morris-Stiff et al. pointed out that the pain may be caused by irritation to the nerves by tacks, glue or mesh itself, an inflammatory reaction against the mesh or simply scar tissue [Citation23]. A notable issue is that the tacks which were used in the hybrid group absorb in less than 12 months and hence should have less effect on pain at 1-year as such. We also used lightweight mesh in the hybrid group. According to O’Dwyer et al., the use of a lightweight mesh may be associated with significantly less pain during exercise, and reduces the sensation of a foreign object compared with standard mesh [Citation24]. This was in disagreement with our results in which the hybrid group experienced more pain.

All nine SF-36 scale scores favoured the rVHR procedure, but only emotional and social functioning achieved a statistically significant difference. Even though VAS was preoperatively as high as 6.6 vs 5.7 (hybrid vs rVHR) and decreased significantly at 1-month and at 1-year follow-up, physical functioning did not increase, which was against our hypothesis. According to Ahonen-Siirtola et al., closing the defect reduces physical impairment [Citation25]. In our study, some of the patients had back pain and knee or hip arthrosis, which was reported to decrease the QoL and may have had an influence on our results.

Seroma-related infections are rather common problems, which can lead to mesh infection and, therefore, hernia recurrence [Citation26]. According to some recent studies, robotic-assisted repair is associated with recurrence rates as low as 1.5–3.7% [Citation8,Citation15] and hybrid repair about 4.8% [Citation11,Citation13,Citation27]. This is in line with our study. According to Morris-Stiff et al., pain is more often associated with recurrent hernia surgery [Citation23]. Despite 100% fascial closure in both groups, one seroma and hernia recurrence occurred in the hybrid group, both in the same patient, although the rVHR group underwent significantly more extensive dissection. International Endohernia Society [Citation28] guidelines introduced a recommendation for tension-free fascial closure. As stated in the guidelines and shown in our study, the rVHR method eliminates bulging and hernia recurrence, and decreases the seroma incidence. In addition, operation time was significantly longer in the rVHR group. No correlation between hernia recurrence and seroma formation or other known risk factors (BMI > 30 kg/m2, comorbidities, ASA class, age) was observed, presumably due to the small number of recurrent hernias. According to the literature, most hernia recurrences occur during the first 2 years after the repair [Citation29–31]. In this respect, a 1-year follow-up is rather short, and therefore the follow-up for the patients included in this study will continue up to 4 years.

Our study had some limitations. Patients were not randomized. We also used two types of meshes in this study. We could not use the uncoated self-adherent polyester mesh in the hybrid group, because it cannot be used against the bowel. We used two kinds of approach to fix the mesh. Furthermore, we had only 38 patients (19 + 19) in this study and the follow-up period was only 1 year. On the other hand, we had no missing data. Long-term follow-up will further establish the safety, efficacy and the benefits of the robotic technique.

In conclusion, our results suggest that hernia repair patients have significantly less chronic pain and less hernia recurrence at 1-year follow-up after rVHR when compared to patients undergoing the hybrid technique. In addition, emotional status and social functioning improves significantly with rVHR. A prospective randomized trial is warranted to confirm the findings of this pilot study.

Geolocation details

This study was conducted in Kuopio University Hospital Finland.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ASA | = | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BMI | = | body mass index |

| hybrid | = | LVHR with primary closure of the defect |

| LVHR | = | Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair |

| QoL | = | quality of life |

| rVHR | = | robotic-assisted ventral hernia repair |

| VAS | = | visual analogue scale |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Fitzgibbons RJ, Richards AT, Quinn TH. Open hernia repair. 6th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Decker; 2007.

- Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM. The biological basis of modern surgical practice. 19th ed. New York (NY): Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Breuing K, Butler CE, Ferzoco S, et al. Incisional ventral hernias: review of the literature and recommendations regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery. 2010;148(3):544–558.

- Kaafarani HMA, Kaufman D, Reda D, et al. Predictors of surgical site infection in laparoscopic and open ventral incisional herniorrhaphy. J Surg Res. 2010;163(2):229–234.

- Muysoms FE, Miserez M, Berrevoet F, et al. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13(4):407–414.

- Burger JWA, Luijendijk RW, Hop WCJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg. 2004;240(4):578–585.

- Tandon A, Pathak S, Lyons NJ, et al. Meta-analysis of closure of the fascial defect during laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2016;103(12):1598–1607.

- Gonzalez AM, Romero RJ, Seetharamaiah R, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with primary closure versus no primary closure of the defect: potential benefits of the robotic technology. Int J Med Robot. 2015;11(2):120–125.

- Warren JA, Cobb WS, Ewing JA, et al. Standard laparoscopic versus robotic retromuscular ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(1):324–332.

- Cocozza E, Berselli M, Latham L, et al. Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernia in a laparoscopic experienced surgical center: low recurrence rate, morbidity, and chronic pain are achievable. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24(2):168–172.

- Chelala E, Barake H, Estievenart J, et al. Long-term outcomes of 1326 laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernia repair with the routine suturing concept: a single institution experience. Hernia. 2016;20(1):101–110.

- Rea R, Falco P, Izzo D, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with primary transparietal closure of the hernia defect. BMC Surg. 2012;12(1):S33.

- Clapp ML, Hicks SC, Awad SS, et al. Trans-cutaneous closure of central defects (TCCD) in laparoscopic ventral hernia repairs (LVHR). World J Surg. 2013;37(1):42–51.

- Berger D, Bientzle M, Muller A. Postoperative complications after laparoscopic incisional hernia repair. Incidence and treatment. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(12):1720–1723.

- Allison N, Tieu K, Snyder B, et al. Technical feasibility of robot-assisted ventral hernia repair. World J Surg. 2012;36(2):447–452.

- Bittner JG, Alrefai S, Vy M, et al. Comparative analysis of open and robotic transversus abdominis release for ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(2):727–734.

- Chen YJ, Huynh D, Nguyen S, et al. Outcomes of robot-assisted versus laparoscopic repair of small-sized ventral hernias. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(3):1275–1279.

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–213.

- Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483.

- Kudsi OY, Paluvoi N, Bhurtel P, et al. Robotic repair of ventral hernias: preliminary findings of a case series of 106 consecutive cases. Am J Robot Surg. 2015;2(1):22–26.

- Gokcal F, Morrison S, Kudsi OY. Robotic retromuscular ventral hernia repair and transversus abdominis release: short-term outcomes and risk factors associated with perioperative complications. Hernia. 2019;23(2):375–385.

- Petro CC, Zolin S, Krpata D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of robotic vs laparoscopic ventral hernia repair with intraperitoneal mesh: the PROVE-IT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1):22–29.

- Morris-Stiff GJ, Hughes LE. The outcomes of nonabsorbable mesh placed within the abdominal cavity: literature review and clinical experience. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(3):352–367.

- O’Dwyer PJ, Kingsnorth AN, Molloy RG, et al. Randomized clinical trial assessing impact of a lightweight or heavyweight mesh on chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2005;92(2):166–170.

- Ahonen-Siirtola M, Nevala T, Vironen J, et al. Laparoscopic versus hybrid approach for treatment of incisional ventral hernia: a prospective randomised multicentre study, 1-year results. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(1):88–95.

- Mercoli H, Tzedakis S, D’Urso A, et al. Postoperative complications as an independent risk factor for recurrence after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: a prospective study of 417 patients with long-term follow-up. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(3):1469–1477.

- Banerjee A, Beck C, Narula VK, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair: does primary repair in addition to placement of mesh decrease recurrence? Surg Endosc. 2012;26(5):1264–1268.

- Bittner R, Bingener-Casey J, Dietz U, et al. International Endohernia Society (IEHS) guidelines for laparoscopic treatment of ventral and incisional abdominal wall hernias (International Endohernia Society (IEHS)-part 1. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(1):2–29.

- Sauerland S, Walgenbach M, Habermalz B, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgical techniques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:CD00.

- Höer J, Lawong G, Klinge U, et al. Factors influencing the development of incisional hernia. A retrospective study of 2,983 laparotomy patients over a period of 10 years. Chirurg. 2002;73(5):474–480.

- Fink C, Baumann P, Wente MN, et al. Incisional hernia rate 3 years after midline laparotomy. Br J Surg. 2014;101:51–54.