Abstract

Objective: To assess the occurrence of interproximal grinding as a caries therapy in primary molars, to what degree grinding replaced conventional restorative caries therapy, to what extent anaesthesia was used while grinding and to assess open comments about attitudes about grinding.

Materials and methods: A questionnaire was sent to 108 public dental service clinics with questions concerning the use of grinding as a therapy and alternative to restorative treatment, the use of anaesthesia prior to conventional caries therapy and grinding, respectively. In addition, a content analysis of open comments about grinding was performed.

Results: Grinding had been performed in 96% of the clinics. Two-thirds of the dentists used grinding as an alternative to conventional restorative treatment at some point. Most dentists used anaesthesia prior to restorative therapy. Prior to grinding, the frequency of anaesthesia was lower (median 5.0) than for conventional restorative therapy (median 8.7) (p < .001). The open comment analysis revealed complex reasons for the use of grinding.

Conclusions: Grinding has been widely practiced in parts of Sweden, is presently a technique employed by a multitude of dentists, and that anaesthesia is used less frequently prior to grinding, in comparison to conventional restorative therapy. Dentist considered grinding as a treatment option in specific situations.

Introduction

Grinding of interproximal caries lesions in primary teeth have been used for close to 80 years, but this method is rarely mentioned in literature. Very few publications have described interproximal caries grinding, with none of them being a controlled study. Most literature on the subject is in older reports in either Norwegian or Swedish [Citation1–4]. This is in contrast to the vast volume of papers on a similar contiguous topic, the orthodontic interproximal grinding of permanent teeth in order to obtain space. This paper is solely on interproximal grinding of caries lesions in primary molars.

In the 1940s, a Norwegian dentist, Sannerud, found that the caries situation among children in Norway was unsustainable and saw the need for a rational method of treatment of caries in primary teeth. At that time, restorative treatment of primary teeth caries was rare. Sannerud started treating children from the age of three years, during which he included grinding of interproximal caries lesions in primary canines and molars. The goal of this grinding was to achieve self-cleaning surfaces and to retain the contact points, thereby maintaining space in the dental arches. In this way, the 1st permanent molar was prevented from erupting adjacent to a primary 2nd molar caries lesion. Grinding was typically carried out with carborundum disks. The technique has for this reason been termed ‘disking’, in the modest volume of available literature on the subject. After 10 years of working with grinding, Sannerud concluded it to be a functional, time-efficient, simple and useful method for treating caries in the primary dentition [Citation1].

In the 1970s, primary teeth were repaired to a greater extent than previously within the public dental service in Sweden. As previously in Norway, the lack of resources created a need for a simplified operational caries therapy for the treatment of abundant caries in the primary dentition. Authorities in dentistry held interproximal grinding as a simple and economical alternative to conventional repair therapy or no therapy. Interproximal grinding was typically used in primary teeth, with the most suitable surfaces suggested for grinding to be the interproximal surfaces between the primary 1st and 2nd molars, in addition to the upper central incisors [Citation2,Citation3].

Svärdström [Citation3] stated that interproximal grinding could be an appropriate choice of therapy in pediatric patients with high rates of caries and in children with limited endurance. The interproximal surfaces between the primary 1st and 2nd molars were considered best suited for the therapy. Grinding of the distal surface of the 2nd primary molar was not recommended due to the risk of mesial drift of the 1st permanent molar. In contrast, Ingers [Citation2] considered interproximal grinding as a technically difficult therapy that required a calm and cooperative patient. Grinding was stated as a treatment option preferable only to a complete lack of treatment. Grinding of primary molars in connection to treatment of an anaesthetized 1st permanent molar is mentioned to be advantageous. Grinding is also claimed to allow better access of fluoride to the mesial surface of the 1st permanent molar. Observed drawbacks were mesial drift of permanent teeth located behind the 1st and 2nd primary molars, in addition to dentinal hypersensitivity and food impaction [Citation2].

In the early 1980s, a slightly more restrictive approach to the use of interproximal grinding appeared. The treatment was not fully considered to be compatible with modern pediatric dentistry. The method was claimed to pose possible risks of pulp damage, food impaction and space loss. Despite the risk of possible adverse effects, grinding could be considered useful in situations where the filling retention could not be created, if the time of tooth exfoliation was close in time, or if the child was not mature enough for conventional treatment [Citation5].

Mesial drift of 1st permanent molars and subsequent lack of space due to grinding of primary molars has been stated as one of the major disadvantages with the therapy [Citation2,Citation3,Citation5]. Further research examined the space in the canine-premolar area after either conventional filling therapy or grinding in primary molars; the results showed no significant loss of space in the canine-premolar area using either of the methods [Citation6].

In the 1990s, grinding, from that time on also called hygiene grinding, was used more restrictively due to observed and recorded side effects, such as secondary caries and tooth movements. From this time, the method was primarily used on 2nd primary molar distal surfaces, to prevent caries on the mesial surfaces of the 1st permanent molars. By the end of the 1990s, the hesitation toward grinding subsided. Prior to the imminent abolishment of amalgam in Sweden, a cheap and efficient treatment alternative for primary tooth caries was demanded, with interproximal grinding being such a potential treatment [Citation4].

In a current textbook for dental students in Sweden, grinding of primary molars is not mentioned as a possible treatment option [Citation7]. Although grinding presently is not taught at dental schools, due to lack of scientific evaluation and not being evidence-based, it has emerged as a common form of treatment in parts of Sweden [Citation8].

In pediatric dentistry, there is a scientific uncertainty about the best available restorative treatment of primary teeth. There is, e.g. insufficient evidence for recommendations regarding which technique is the most appropriate [Citation9]. In a recent review, the evidence for the effects of interventions in primary teeth was low or very low [Citation10]. At the same time, as conventional filling therapy and caries excavation techniques are not fully evaluated, interproximal grinding is not evaluated at all. High-quality data is more or less absent for grinding therapy.

The aim of this study was to perform an inventory among general practitioners of interproximal grinding of primary molars, how often grinding replaces conventional caries therapy, to what extent anaesthesia was used when grinding in relation to conventional filling therapy, and an assessment of attitudes towards grinding.

Materials and methods

Respondents were general practice dentists working in the public dental service in the county of Västra Götaland, Sweden. One hundred eight clinics were contacted for information about the study. One hundred five of the clinics responded. From these clinics, 433 dentists responded to the inquiry.

Quantitative analysis

Questionnaires were sent to all participating clinics, where each respondent answered questions regarding the clinic name, year of license, gender, and place of education. Question No. 1 was answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Questions No. 2–5 were answered with a VAS-value between 0–10; the 0-value meant ‘never’ or ‘do not agree’, whereas the 10-value meant ‘always’ or ‘fully agree.’

Content analysis of qualitative data

For each question, it was possible to leave open comments in order to provide an explanation for a better understanding of the thoughts and reasons behind the mark on the VAS scale. The open comments were analyzed using a model for conventional content analysis [Citation11,Citation12]. All comments from questions 1–5 were divided into categories of answers. Significant words in the open comments were included as codes, with these comments grouped into subcategories and finally, categories. Grouping in categories took place independent of the respondents’ estimates on the VAS-scale and independent of the frequency of the response options. The category outcomes were finally compiled into a comprehensive theme.

Ethical aspects

No personal data are found in the study. All respondents participated voluntarily in the study and the questionnaires were filled out anonymously. The participants’ anonymity was maintained in all information linked to specific clinic affiliations. Background information, year of license to practice, gender, place of education, and how respondents estimated on the VAS-scales of questions 1–5, were reported on a consolidated basis. Open comments were not related to individual persons.

Statistics

Statistics were performed with the R statistical package (free shareware, The R Project for Statistical Computing. ©The R Foundation). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used in order to identify possible differences between gender, year of license to practice, and place of education. In case of statistical significance, the analysis was extended with the Nemenyi post-hoc test, in order to identify places of differences. For multiple comparisons, a false discovery rate was used in order to correct p-values. For comparison between questions 4 and 5, the Mann–Whitney U test was used. A p-level <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Quantitative data

The clinic response rate was 97%. On an average, each clinic accounted for 4.1 responding dentists. A total of 433 dentists responded. Of these, 48% had their dental degree after the year 2000, with the rest ranging from the 1950s to the 1990s. Sixty seven percent of the participants were women, 70% of the respondents had received their dental training in Gothenburg, Sweden and 11% outside of Sweden. Of those educated outside of Sweden, 73% had received their education in an European country.

Question 1. ‘Have you ever used grinding as an alternative to conventional operative caries treatment?’ In 96% of the clinics, at least one dentist used, or had used, grinding as a caries therapy. The proportion of all dentists who answered yes was 65%.

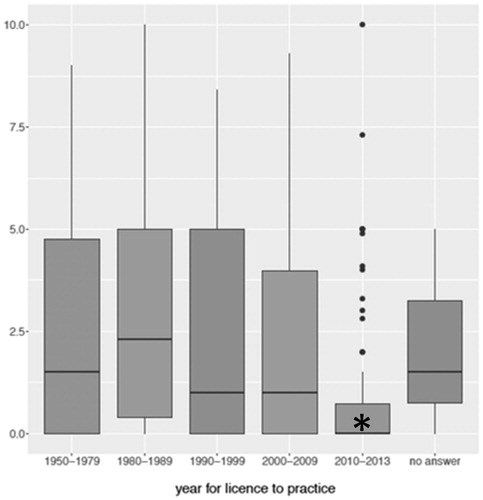

Question 2. ‘To what extent have you used/are you using grinding as an alternative to conventional operative caries treatment?’ When comparing groups by year of license, it was revealed that dentists with licenses from 2010 to 2013 showed a statistically significant lower (p<.05) tendency to replace conventional operative therapy with grinding, in comparison to dentists who received their license between 1950–2009. There were no statistically significant differences between gender or place of education for question 2 ().

Figure 1. To what extent have you used/are you using grinding as an alternative to conventional operative caries treatment? The boxes denotes 50% of the cases. The lines across boxes denotes medians. Dentists with licenses from 2010 to 2013 showed a statistically significant lower tendency to replace conventional operative therapy with grinding (p < .05). There were no statistically significant differences between gender or places of education.

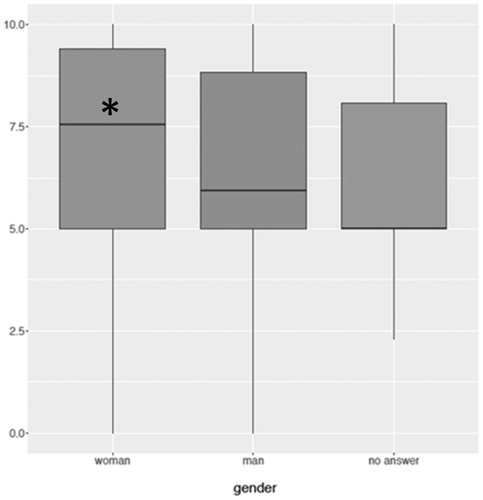

Question 3. ‘I always treat dentinal caries with operative treatment (not regarding incisors) if the tooth is not expected to last until normal exfoliation.’ Female dentists were statistically more (p < .05) prone to treat dentinal caries in primary teeth than men. There were no differences for place of education or year of license ().

Figure 2. I always treat dentinal caries with operative treatment (not regarding incisors), if the tooth is not expected to last until normal exfoliation. The boxes denotes 50% of the cases. The lines across boxes denotes medians. Female dentists were more prone to treat dentinal caries in primary teeth than men (p < .05). There were no statistically significant differences between places of education or year for license.

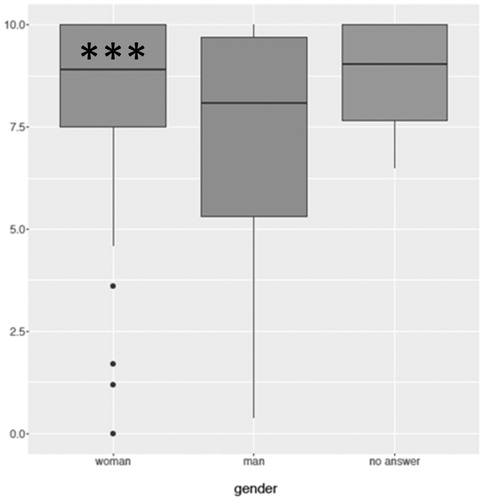

Question 4. ‘To what extent do you anaesthetize before carrying out conventional operative caries treatment in dentin?’ Female dentists anaesthetized statistically more frequently (p < .001) before treatment, when compared to male dentists. There were no statistically significant differences regarding place of education or year of license ().

Figure 3. To what extent do you anaesthetize before carrying out conventional operative caries treatment in the dentin? The boxes denotes 50% of the cases. The lines across boxes denotes medians. Female dentists anesthetized statistically more frequently compared to male dentists (p < .001). There were no statistically significant differences regarding places of education or year of license.

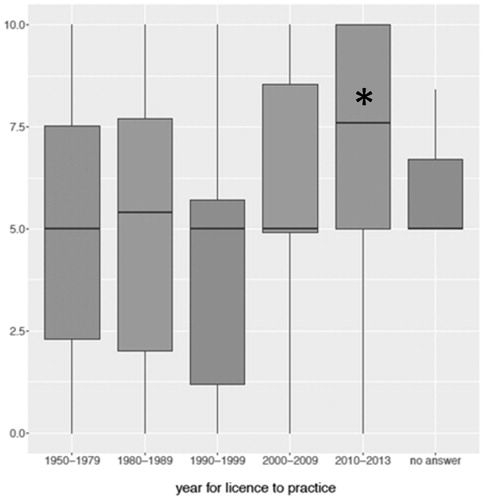

Question 5. ‘To what extent do you anaesthetize before carrying out grinding in dentin?’ Dentists with degrees from 2010–2013 anaesthetized to a greater extent (p < .05) when grinding, than dentists with degrees from 1980–2009. There were no statistically significant differences regarding gender or place of education ().

Figure 4. To what extent do you anaesthetize before carrying out grinding in the dentin? The boxes denotes 50% of the cases. The lines across boxes denotes medians. Dentists with degrees from 2010–2013 anaesthetized statistically more often when grinding (p < .05). There were no differences regarding gender or places of education.

When comparing estimates of questions 4 and 5, there was a statistically significant difference (p < .001) between the use of anaesthesia during conventional operative treatment, when compared to grinding, with the use of anaesthesia being less frequent for grinding.

Qualitative data

Significant words, ‘codes’, from all free text comments were extracted, analyzed, and categorized into eight code groups. From the code groups, eight subcategories were formulated: Good method, no anaesthesia, certain situations, grinding sometimes, anaesthesia sometimes, used grinding previously but not now, do not use grinding for economic reasons, seen problems, and warned against grinding. The subcategories ‘good method’ and ‘no anaesthesia’ are characterized by positive codes, e.g. obtain good hygienic conditions, better access to fluoride and no need for anaesthesia. The subcategories ‘some situations’ and ‘anaesthesia sometimes’ are characterized by codes describing suitable situations for the use of grinding, e.g. short time to exfoliation, no retention for conventional filling and behavioral management problems. Codes describing advantages of no need for anaesthesia are: anaesthesia sometimes, depending on age, cooperation, and in cases with small cavities. The subcategories ‘used the method earlier’ and ‘no treatment for economic reasons’, introduces codes with hesitant values such as, abandoned method after drawbacks like pain, dentinal hypersensitivity, food impaction and new caries. No caries treatment for economic reasons is also mentioned. The subcategories ‘seen problems’ and ‘warned against’ are characterized by negative codes, e.g. dentinal hypersensitivity, food impaction, makes caries worse and bad final result. Also, warned for grinding, is mentioned.

From the subcategories, four categories were formulated: Good method/advantages/no anaesthesia, certain situations/anaesthesia sometimes, used grinding previously but not now, do not use grinding/disadvantages. The category contents range from positive comments to hesitant comments. Finally, the categories were compiled into an overall comprehensive theme: Grinding can, during special circumstances, be a simpler treatment technique for primary molar caries. The theme summarizes a will to treat in a rapid, simple, and time-efficient way, where two aspects appear: Grinding is simpler to perform than conventional filling therapy and anaesthesia is not always necessary for grinding in primary molars ().

Table 1. Content analysis of qualitative data.

Discussion

This study shows that dentists licensed for four years or less are statistically significantly less prone to use interproximal grinding, as an alternative to conventional filling therapy, than dentists who have had their licence for more than four years. In addition, dentists licensed for four years or less, who employ interproximal grinding, use local anaesthesia at a statistically significantly higher extent than dentists being licensed for more than four years. There is a statistically significant difference between male and female dentists, with female dentists excavating primary teeth at a higher rate, in addition to using local anaesthesia more frequently. This study also shows that dentists use local anaesthesia at a statistically significantly lower extent for interproximal grinding, than for conventional filling therapy.

The findings in this study are in contrast to current recommendations about the management of carious lesions in primary teeth. Two recent reports from the International Caries Consensus Collaboration present clinical recommendations for the treatment of cavitated carious lesions. A causal approach and preservation of hard tissues are fundamental in the recommendations. Restorative interventions are indicated only when carious lesions are non-cleansable. Interproximal grinding as a treatment option is not mentioned [Citation13,Citation14].

A major strength of the present study is the high degree of participation. 97% of all public dental service clinics in the County of Västra Götaland took part in the study. The Västra Götaland county constitutes 16.7% of the Swedish population (January 2018). In all clinics, children were treated on a regular basis. The fall off was three clinics only. The data material contains inquiry answers from 433 respondents from 105 clinics. The answers contained 481 comments from the open question part of the inquiry. These comments were subject to a conventional qualitative content analysis [Citation11,Citation12], aiming at a deeper understanding of the thoughts and decision-making when answering the VAS-scales, as well as the open questions. When using the self-assessment scales, the interpretation of the scale step value lies in the hands of the responders, in this case, the responding dentist. As the values of the scale steps are not defined in the used non-equidistant ordinal scale, interindividual comparisons must be done with precaution. Therefore, the qualitative part of the study comprises of a useful balance to the quantitative part.

A noticeable disadvantage with the analyzed parameter, interproximal grinding, is that a substantial part of the previous literature is in Swedish or Norwegian [Citation1–4], and thus not accessible to most readers. This might reflect either grinding as a typical Scandinavian phenomenon, or as a therapy being widely used, but not being scientifically described or evaluated. There is only one publication on a similar subject in English. In Mijan et al. (2014), three different treatment protocols of dentin caries in primary molars were evaluated; one of them being the opening and enlargement of medium-sized cavities in order to facilitate biofilm removal with a toothbrush. The 3.5-year tooth survival of this treatment strategy did not differ statistically significantly from conventional restoration therapy. This study may give some support for the idea of exposing interproximal carious lesions, in order to create self-cleansing surfaces. However, despite the striking lack of scientific evaluation, interproximal grinding has gained widespread foothold. [Citation15].

An aim of this study was to assess the extent of use of interproximal grinding. Some of the answers show that the responders, in addition to grinding between primary molars, also include grinding between maxillary primary incisors. Although from the comments, it is shown that the vast majority of the responders consider grinding as a treatment method primarily for interproximal caries between primary molars.

The inquiry question No. 1 ‘Have You ever used grinding as an alternative to conventional operative caries treatment?’, included responders irrespective of how often the technique had been used. The individual frequency of use was assessed in subsequent questions. It was shown that approximately 65% of all responders, on some occasion, had employed interproximal grinding as a method of treatment for caries in primary molars. In the open comments to question No. 1, considerable differences in the view and experience of grinding appears. Some dentists use grinding frequently, whereas others use the technique more selectively only for some teeth, and/or in certain situations. Open comments vary between ‘good therapy, have good experiences of this’, and ‘1st primary molars very seldom’, demonstrating a vast spectrum of opinions concerning the technique. In some clinics, grinding does not occur, whereas in others, it is frequently used. Similarly, evident differences were observed even within clinics, with frequent users and non-users working side-by-side.

During the 1970s–1980s, dental program course literature in cariology and pedodontics included recommendations for the use of interproximal grinding in primary molars. It is possible that grinding, at that time, was accepted as a fully adequate therapy form and that grinding traditions within individual clinics have survived until today. In many of the open comments to question No. 1, references to older colleagues occur. Comments like ‘in the beginning of my career upon recommendation of colleagues’, shows that young professionals easily adopt the methods of more experienced colleagues in spite of lack of evidence. Clinical routines taught in dental school are easily overridden, when presented with an easier treatment option. In this way, treatment forms, not recommended in dental schools, can abide long after their teaching.

From inquiry question No. 2, ‘To what extent have you used/are you using grinding as an alternative to conventional operative caries treatment?’, it was shown that dentists with the shortest work experience were those using grinding the least (). A low median VAS-value for question No. 2 indicates that grinding is practised, but that conventional filling therapy is more frequently used. Mansour-Ockell and Bågesund [Citation16] found that in primary molars, extracted for cariological reasons in 3-8-year-olds, a major part had been subjected to grinding prior to extraction. Notably, nearly every second responder was a year 2000 or later graduate, possibly reflecting that interproximal grinding has not been a part of dental school curriculum since the 1990s, at which time, evidence-based dental training was introduced. In spite of this, the implementation of up-to-date routines is not fully effected; the use of interproximal grinding being a striking example.

Free text comments to question No. 3 ‘I always treat dentinal caries with operative treatment (not regarding incisors) if the tooth is not expected to last until normal exfoliation’, shows that quite a number of dentists do not agree. Women were statistically more prone to treat dentin caries than men (). Frequent comments from respondents reveals a strategy where primary tooth caries is left untreated, leaving the teeth for future extraction in case of pain. Comments like ‘unless it´s not pulp involvement I expect, in order to extract in case of pain’ or ‘I do not excavate primary molars in case of many cavities, in these cases extraction if painful’ reflect this. In some comments, clinic economy is put forth as a reason not to treat primary tooth caries. Comments like ‘we are not allowed to treat in this clinic’ or ‘we try to cut down treatments in order to save money’ or ‘we are not allowed to excavate for economic reasons’ reflect this.

Inquiry questions No. 4 and 5 regard the use of anaesthesia during conventional excavation and interproximal grinding. Women anaesthetized statistically more frequently during excavation than men (). Similarly, dentists licensed after 2000 anaesthetized statistically more frequently during grinding (). Dentists anaesthetized statistically significantly less when grinding than in conventional excavation therapy. Free text comments exhibit a wide range of opinions in this matter. Comments range from ‘few kids can deal with this without anaesthesia, especially primary molars’ or ‘the whole point is not to anaesthetize’, in addition to ‘ongoing root resorption makes treatment painless’. Many of the answers describe the initiation of grinding or excavation without anaesthesia, stopping in case of pain. The fact that dentin, including primary tooth dentin, is sensitive for cutting is undisputable. In a study by Wondimu and Dahllöf [Citation17], 83% of Swedish dentists claim that dental care on children should be carried out in the absence of pain. Concurrently, 39% believe that children must be prepared to experience some degree of pain in association with dental care, and 32% believe that painless dentistry is a utopia. That study also shows that 29% of the dentists found it stressful to administer anaesthesia in preschool children. A study by Rasmussen et al. [Citation18] shows a similar approach to anaesthesia among Danish dentists. In this study, over 80% said that pain relief during dental care to children is important, but at the same time, a third of the dentists considered that pain is a part of life and that total pain relief during dental care to children is a utopia. It is perhaps this attitude to pain and anaesthesia that is reflected in the present study. The therapists first try without anaesthesia in a hope of not needing to anaesthetize.

In a recent review, the evidence for the effects of interventions in primary teeth was low [Citation10]. There is insufficient evidence for recommendations regarding which technique is the most appropriate for restorative treatment in primary teeth [Citation9]. There is no published controlled study that evaluates treatment outcome, prognosis or patient experience following interproximal grinding in primary molars. Thus, it is not possible to claim whether grinding is an appropriate treatment method in comparison to conventional filling therapy. The fact that grinding is not taught in dental schools anymore is primarily based on the absence of evidence.

Dental care providers such as the Public Dental Health Service, and organizations such as the Swedish Society for Pediatric Dentistry, compile guidelines based on the best available evidence. Approximal grinding is not a recommended clinical routine and is not part of the curriculum in dental schools. The ethics of using grinding as a treatment option, and performing it out without anaesthesia, can be discussed.

The conclusions of this study are in agreement with Arvidsson et al. [Citation8].

Grinding had been practised in almost all clinics and by two-thirds of all responding dentists.

Dentists who have gained their licence to practice after the year 2000 are less likely to use grinding as a treatment.

Females were more prone to treat caries than men and used anaesthesia more frequently than men during excavation.

Anaesthesia is used less frequently during grinding than during conventional excavation.

From the qualitative analysis of free comments, it is shown that grinding is considered simpler to perform than conventional filling therapy, and anaesthesia is not always considered necessary for grinding in primary molars.

The use of interproximal grinding lacks a base of evidence. Therefore, controlled studies of outcome and patient experience is needed prior to a decision about whether it is a treatment form justified in pediatric dentistry.

Acknowledgements

The participation of all responders among the clinics is hereby acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Sannerud OR. Er en rasjonell og forenklet terapi av caries i melketannsettet forsvarlig og hensiktsmessig? [Is a rational and simplified caries therapy in primary teeth defensible and intentional?]. Göteborgs Tandläkare-Sällskaps Årsbok. 1953;46–55. Norwegian.

- Ingers G. Modifierad kariesterapi på barn med växelbett [Modified caries therapy in children with primary teeth]. Tandläkartidningen. 1972;64:255–258. Swedish.

- Svärdström G. Modifierad fyllningsterapi för mjölktänder [Modified filling therapy for primary teeth]. Tandläkartidningen. 1972;64:81–85. Swedish.

- Ek PG, Forsberg H. Hygienslipning i det primära bettet [Hygiene grinding in primary teeth]. Tandläkartidningen. 1994;86:612–620. Swedish.

- Hallonsten AL, Magnusson BO, Rølling I. Operative dentistry, prosthetics. In: Magnusson BO, editor. Pedodontics – a systematic approach. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard; 1981. p. 197–232.

- Ingers G, Cromvik U, Gleerup A, et al. The effect on space conditions of unilateral grinding of carious proximal surfaces of primary molars – a longitudinal study. ASDC J Dent Childr. 1982;49:30–34.

- Julihn A, Grindefjord M, Espelid I. Diagnosis and management of dental caries. 3rd ed. In: Koch G, Poulsen S, Espelid I, Haubek D., editors. Pediatric dentistry. A Clinical approach. Blackwell (UK): Wiley; 2017. p 130–160.

- Arvidsson A, Danell M, Karlsson U. An inventory of the occurrence and circumstances regarding proximal grinding in caries treatment in the primary dentition – a survey study in Västra Götalandsregionen, Sweden [master’s thesis]. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg; 2010.

- Duangthip D, Jiang M, Chu CH, et al. Restorative approaches to treat dentin caries in preschool children: systematic review. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2016;17:113–121.

- Mejàre IA, Klingberg G, Mowafi FK, et al. A systematic map of systematic reviews in pediatric dentistry–what do we really know? PLoS One. 2015;10:1–21.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288.

- Schwendicke F, Frencken JE, Bjørndal L, et al. Managing carious lesions: consensus recommendations on carious tissue removal. Adv Dent Res. 2016;28:58–67.

- Banerjee A, Frencken JE, Schwendicke F, et al. Contemporary operative caries management: consensus recommendations on minimally invasive caries removal. Br Dent J. 2017;223:215–222.

- Mijan M, de Amorim RG, Leal SC, et al. The 3.5-year survival rates of primary molars treated according to three treatment protocols: a controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18:1061–1069.

- Mansour Ockell N, Bågesund M. Reasons for extractions, and treatment preceding caries-related extractions in 3–8 year-old children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:122–130.

- Wondimu B, Dahllöf G. Attitudes of Swedish dentists to pain and pain management during dental treatment of children and adolescents. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2005;6:66–72.

- Rasmussen JK, Frederiksen JA, Hallonsten AL, et al. Danish dentists’ knowledge, attitudes and management of procedural dental pain in children: association with demographic characteristics, structural factors, perceived stress during the administration of local analgesia and their tolerance towards pain. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:159–168.