Abstract

Objective: This study is a part of a project with the aim to construct and evaluate a structured treatment model (the Jönköping Dental Fear Coping Model, DFCM) for the treatment of dental patients. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the DFCM from a patient perspective.

Material and methods: The study was performed at four Public Dental Clinics, with the same 13 dentists and 14 dental hygienists participating in two treatment periods. In Period I, 1351 patients were included and in Period II, 1417. Standard care was used in Period I, and in Period II the professionals had been trained in and worked according to the DFCM. In the evaluation, the outcome measures were self-rated discomfort, pain and tension, and satisfaction with the professionals.

Results: In comparison with standard care, less tension was reported among patients treated according to the DFCM, (p = .041), which was also found among female patients in a subgroup analysis (p = .028). Additional subgroup analyses revealed that patients expecting dental treatment (as opposed to examination only) reported less discomfort (p = .033), pain (p = .016) and tension (p = .012) in Period II than in Period I. Patients with low to moderate dental fear reported less pain in Period II than in Period I (p = .014).

Conclusions: The DFCM has several positive effects on adult patients in routine dental care. In a Swedish context, the differences between standard care and treatment according to the model were small but, in part, statistically significant. However, it is important to evaluate the model in further studies to allow generalization to other settings.

Keywords:

Introduction

Dental fear is among the most commonly reported fears or phobias [Citation1]. Studies show that between 10% and 27% of adult patients experience moderate to high dental fear [Citation2–4], and 4–6% suffer from phobic dental fear [Citation2,Citation5]. In cross-sectional studies, the prevalence of dental fear has been shown to be stable over time [Citation6,Citation7], but a recent Swedish study showed that the prevalence decreased over a time span of 50 years [Citation2].

The concepts of dental anxiety and dental fear are often used interchangeably in the literature, as both express conditions that involve (negative) patient cognition and experiences of dental treatment [Citation8]. In the present study, the concept ‘dental fear’ will be used consistently. An increase in perceived apprehension towards possible or real threats in the dental situation may elicit emotional, cognitive, physiological and behavioural responses in patients exposed to fear-provoking stimuli. Dental fear has been shown in longitudinal studies to increase in younger adults and decrease in middle-aged and older adults [Citation9,Citation10], but for many individuals, dental fear is stable during life [Citation3]. If dental fear persists over a long time, it may lead to severe psychosocial consequences, irregular dental attendance or total avoidance of dental care, as well as impaired oral health among dental patients [Citation11–14].

There are different physical manifestations of dental fear among patients. A Norwegian study showed that patients with high fear levels scored high on a question referring to feeling unwell or nausea during dental treatment (discomfort other than pain), which was positively correlated with the time since the last dental visit [Citation15]. In a British qualitative study, muscular tension was identified as a manifestation of dental fear in the dental setting [Citation16]. Pain is a subjective, complex, multifactorial experience [Citation17], defined as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’ [Citation18]. Pain (and other negative experiences) associated with dental procedures and dental fear is well described in the literature [Citation19–23]. The association between pain, dental fear and patient satisfaction has also been studied [Citation24,Citation25]. In these epidemiological studies, dental fear was not significantly correlated with patient satisfaction. However, the authors reported a positive relationship between non-attendance and increased levels of pain, dental fear and unpleasantness during recent dental visits.

Negative experiences leading to dental fear, such as traumatic dental treatment and sexual abuse, have been reported [Citation26,Citation27]. In an Australian study [Citation28], a majority of fearful patients (with low and high dental anxiety) reported having had one or more negative dental experiences, like ‘pain’, ‘discomfort’, ‘gagging’, ‘fainting or feeling light-headed’, ‘embarrassment’ or ‘having a personal problem with the dentist’. In the same study, in the high dental anxiety group, avoiding dental visits was predicted by ‘difficulty paying a 300-dollar dental bill’, ‘having no/little trust in the last dentist visited’, ‘having perceived treatment need’, and ‘having dental anxiety’, in the high dental anxiety group. In the low anxiety group, avoidance was predicted by ‘perceived treatment need’, and ‘dental anxiety’. In order to reduce avoidance, the authors suggested that improved communication skills and realistic information by dental health professionals would make patients better understand their dental status and perceived treatment need.

We believe there is a need for routines for dental health professionals in their interaction with fearful dental patients [Citation29], to detect and understand the nature of the fear. Within the project, we designed and evaluated the Jönköping Dental Fear Coping Model (DFCM), and used it in the treatment of adult patients with all levels of dental fear, from the perspective of both health professionals and patients. In the present study, we focussed on the patients and used cross-sectional data. We compared two groups of patients: one group that was treated at one of four study clinics before their staff had been trained in the DFCM (‘Period I’), and one group that was treated at the same clinics after the DFCM regimen had been introduced. By including patients unselectively, we expected to have a portion of patients with low to moderate fear, a patient category not often focussed on in research. The DFCM and the training in the model are explained in detail elsewhere [Citation30]. Our hypotheses were the following: patients attending the study clinics after the introduction of the DFCM (Period II) report less discomfort, pain and tension, and greater satisfaction with the dental health professionals they meet, compared with patients attending the study clinics before the introduction of the DFCM (conventional treatment). By comparing how the two patient groups react to their treatment, we hope to gain knowledge about the effects, if any, of the DFCM.

Material and methods

The Jönköping dental fear coping model (DFCM)

The Jönköping DFCM was developed with the aim to reduce stress reactions among dental health professionals and fearful patients in the treatment situation. Besides improving the working environment for the professionals, the purpose of the DFCM is to prevent the onset of fear and reduce manifest dental fear among patients. The model is based on the Seattle system [Citation31], Ditt valg [Citation32,Citation33], and motivational interviewing (MI) [Citation34]. A new patient category, fearless/no fear, was added to the four existing categories in the Seattle system. The different response cards from Ditt valg, reflecting the diagnostic categories in the Seattle system, provide the dental health professionals with information on how to treat a patient with a particular dental fear profile. The way the professionals were instructed to communicate with the patients was guided by the principles of MI.

The model requires that all new patients respond to an electronic pre-treatment questionnaire about dental fear, including one global question, ‘are you afraid of going to the dentist?’ (DAQ) [Citation35], and a dental fear index, the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C+) [Citation36,Citation37] (see ‘Instruments’ section below). Patients responding in the affirmative to the global question or to any of the questions in the first module of the IDAF-4C + proceeded to Ditt valg, while the non-fearful did not. The questionnaire is completed in the waiting room prior to the dental examination. An algorithm then summarizes the responses in a dental fear summary, which the health professionals receive before seeing the patient. The dental fear summary provides the health professionals with information about (1) the patient’s level of dental fear (none to extreme), (2) the fearful patient’s experiences and expectations of the dental treatment (retrieved from Ditt valg) [Citation32,Citation33], and (3) a dental fear category/categories according to the Seattle system [Citation31]. Hence, the dental health professionals are prepared and can use the information about the patient during the subsequent appointment. The open-ended questions, reflective listening, affirmations, and summaries according to MI enhance the communication between the patient and the professionals [Citation34].

Procedure

Study design

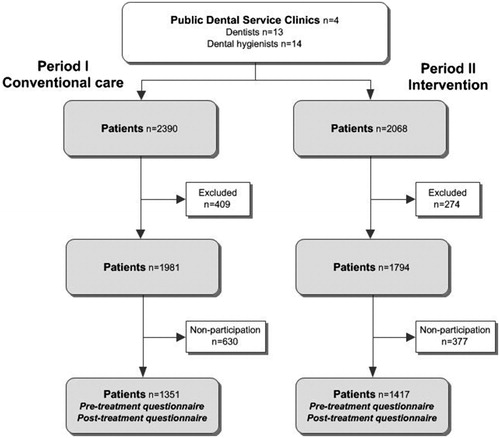

Following a randomization procedure (matched pairs design), the four study clinics in the present study were selected among the nine clinics used in our previous study [Citation30] to ensure that the geographic areas they serve are representative of the larger group of clinic districts with respect to socio-economic status and being rural/urban. The four clinics were included for both treatment periods: Period I (conventional treatment) and Period II (DFCM-guided treatment). As previously described, there were different patients but the same dental health professionals in the two periods (). Conventional care was carried out in Period I and, after training, the DFCM was used by the dental health professionals in Period II. Data from the two independent patient groups in Period I and II were compared in order to trace effects of the DFCM procedures. The detailed study design has been explained elsewhere [Citation30].

Figure 1. Flow chart illustrating the intervention study; Period I: ‘Conventional care’ and Period II: ‘Intervention’ (DFCM-guided treatment).

The dental patients participating in the study were chosen irrespective of whether they were fearless/fearful, and irrespective of the nature of their appointment; whether they received some kind of dental treatment or only a dental examination. The research administration staff informed and included patients in the study consecutively, as they came to the clinic. In the waiting room, the patients responded to a pre-treatment and a post-treatment questionnaire (see Instruments below), before and after the treatment session, respectively. In Period I, the responses were handled confidentially by the research study staff and could not be accessed by the health professionals. In Period II, the patient’s pre-treatment questionnaire was computerized into the dental fear summary that was given to the health professionals before they were to meet the patients. The initial interaction with the patient was guided by the information condensed in the dental fear summary, aiming at confirmation and clarification. With a patient with no reported signs of dental fear, the dentists or the dental hygienists would just confirm the lack of ‘hang-ups’.

Study sample

The study was performed at four Public Dental Clinics in Region Jönköping County, with the same 13 dentists and 14 dental hygienists participating in Period I and II. The following exclusion criteria for health professionals were applied: working with children only, unable to collect sufficient data due to part-time work, and sickness or parental leave before starting the study. The patients participating in periods I and II are shown in . The following exclusion criteria for patients were applied: Has already participated in the study, severely impaired vision, and problems reading and speaking Swedish. Of 2390 patients who were registered at the four clinics during Period I, 409 were excluded; of the remaining 1981 patients, 630 declined to participate. During Period II, when the DFCM treatment model was applied, 2068 patients were registered; 274 were excluded, and of the remaining 1794, 377 declined to participate. Some reasons given for non-participation were lack of time, reluctance to be enrolled, or not responding to the post-treatment questionnaire. Consequently, the number of patients entering the study was 1351 in Period I, and 1417 in the following Period II (). The participation rate in Period I was 68%, and 79% in Period II.

Instruments

Pre-treatment patient questionnaire

The first questions in the pre-treatment questionnaire asked about the patient’s age, gender and reason for the visit. The response alternatives to the question ‘Do you know what will happen during the visit today?’ were ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. ‘If yes, tick one or several alternatives’: ‘examination’, ‘local anesthesia’, ‘cleaning’, ‘scaling’, ‘filling’, ‘root canal treatment’, ‘tooth extraction’, ‘crown, bridge, denture work’, ‘something else’. The alternative ‘something else’ was open-ended, and the answers were categorized into ‘acute treatment’, ‘acute pain’, ‘mouth guard/splint’, and ‘check-up/control’. A ‘reason for dental visit’ variable was computed (‘do not know’, ‘dental examination’, ‘dental treatment’), in order to make comparisons between patients and of the effect of the DFCM on different subgroups in periods I and II. We used two summary variables: the ‘dental examination’ category include ‘examination’ and ‘check-up/control’, and the ‘dental treatment’ category include all other treatment alternatives.

Dental fear was assessed by means of one global question and a dental fear index. The global question DAQ: ‘Are you afraid of going to the dentist?’ has four response alternatives (‘No’, ‘A little’, ‘Yes, quite’, and ‘Yes, very’) [Citation35]. The dental fear index used was IDAF-4C+ [Citation36,Citation37]. It consists of three modules: the anxiety and fear module, the phobia module and the stimuli module. The anxiety and fear module assesses the emotional, behavioural, physiological and cognitive components of the anxiety, and is used for screening of dental patients, like in the present study. Patients respond to eight items on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). Full-scale scores are given as an average score across the eight items (range 1–5). As suggested by Armfield [Citation8], the following patient levels of dental fear derived from the anxiety and fear module of the IDAF-4: No or little dental fear (1.00–1.50); low dental fear (1.51–2.50); moderate dental fear (2.51–3.50), and high dental fear (>3.50). In the present study, only patients who were categorized as fearful responded to the phobia and stimuli modules (results not shown).

Post-treatment patient questionnaire

The patient’s perceived pain, discomfort and tension/strain during the encounter were measured in the post-treatment questionnaire on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (0–10) with the questions: ‘Did you feel pain during today’s dental exam/treatment?’, with the response options ranging from ‘No, no pain at all’ (VAS = 0), to ‘Yes, the worst imaginable pain’ (VAS = 10); ‘Did you feel any other discomfort during the dental exam/treatment?’: ‘No, no discomfort’ (VAS = 0) to ‘Yes, the worst imaginable discomfort’ (VAS = 10), and ‘How tense were you during the dental exam/treatment?’: ‘Completely relaxed’ (VAS = 0) to ‘Extremely tense’ (VAS = 10). The rating variables were chosen because they represent clinically relevant negative reactions that can hopefully be reduced with the help of DFCM. The patient responded to the questions after treatment, outside the treatment room.

Patient satisfaction with the dentist’s or the dental hygienist’s skills and behaviour was measured using the Patient Attitude Scale [Citation38]. The questionnaire was modified to assess both dentists and dental hygienists, and not only the dentist, as in the original version. For this reason, ‘dentist’ was replaced by ‘dental health professional’ throughout the questionnaire. Further, the authors assessed the first item in the original nine-item questionnaire, ‘The dentist was experienced and skillful’, as being indistinct, describing two professional qualities that do not necessarily assess the same thing. The authors decided to divide the item into (1) ‘The health professional was experienced’, and (2) ‘The health professional was skillful’. These two items, together with (3) ‘The health professional was rough’, and (6) ‘The health professional provided the most painless treatment possible’ are related to the health professional’s skills. The behavioural or interpersonal qualities were addressed with (4) ‘The health professional took time to listen, and had the ability to understand my situation’, (5) ‘The health professional was working in a stressful way and seemed to be pressed for time’, (7) ‘The health professional had a nonchalant and distant attitude’, (8) ‘The health professional had a confident, kind and considerate attitude’, (9) ‘The health professional seemed to be critical of me and my teeth’, and (10) ‘The health professional very clearly told me what he was going to do to my teeth and why it was necessary’. The response alternatives were measured on a scale from ‘Do not agree at all’ (1) to ‘Agree completely’ (5). Total scores were obtained by summing up the responses to the ten items after reversing the coding of the four negatively worded items (items 3, 5, 7, 9). The total score ranged from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher patient satisfaction.

Data analyses

All continuous variables were described by the mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum, and all categorical variables as numbers and percentages. The difference between study groups with respect to continuous outcome variables was described by means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on bootstrapping of 10 000 replicates. For tests between the two groups (Intervention period I vs. II), Fisher’s Exact test was used for dichotomous variables, the Mantel-Haenszel Exact Chi-2 test (Exact Linear-by-Linear Association) for ordered categorical variables, and the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. The relation between two continuous variables was described and tested by the Spearman correlation coefficient (rs). For testing the potential effect of the DFCM for subgroups of patients (dental fear, gender, reason for dental visit), an interaction term between the subgroup and the DFCM was added to a linear regression model with empirical robust standard error adjustment for each patient-reported outcome. No imputation of (missing) data was performed. In and , analyses of the Patient Attitude Scale (PAS) are shown, in total and divided into the professionals’ skills and interpersonal qualities. In order to make comparisons between skills and qualities (4 and 6 items, respectively), the ratings were transformed into z-form. All tests were two-tailed and conducted at a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 24. The number of individuals (in tables) may differ due to missing data.

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Linköping University (Reg. no. 2013/322-31), and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was obtained from health professionals and patients.

Results

provides data on the patients undergoing conventional treatment - Period I, or DFCM treatment - Period II, including gender, dental fear assessed by the global question and by the IDAF-4C, reason for dental visit, and age. The patients in Period I were significantly more fearful and significantly more aware of which treatment they were going to receive than the patients in Period II. However, there were no statistically significant differences in gender or age between the two periods. The patients’ experiences of a treatment session were assessed with the four outcome measures discomfort, pain, tension, and patient satisfaction with dental health professionals. The results were analyzed by comparing ratings after sessions with standard care (Period I), and sessions with the DFCM (Period II). shows such comparisons for each of the four outcome measures. provides subgroup analyses of patient-reported discomfort, pain, tension, satisfaction with professionals (Patient Attitude Scale = PAS) in relation to dental fear (IDAF-4C+), gender, and cause of dental visit in periods I and II. Dental fear was higher at lower ages in both periods (p < .001). Men were less fearful than women in both periods (p < .001).

Table 1. Background data for patients participating in periods I and II: gender, dental fear according to DAQ and IDAF-4C+, reason for dental visit, and age.

Table 2. Patient-reported outcomes for discomfort, pain, tension, and patient satisfaction with dental health professionals (Patient Attitude Scale = PAS) in relation to periods I and II.

Table 3. Patient-reported discomfort, pain, tension, satisfaction with health professionals (Patient Attitude Scale = PAS) in relation to dental fear (DAQ, IDAF-4C+), gender, and cause of dental visit in periods I and II.

Discomfort

Patient-rated discomfort did not differ between the two periods (). When subgroups of fearfulness were compared, dental fear subgrouping according to the IDAF-4C did not reveal any statistically significant differences in self-reported discomfort within different levels of fear between Period I and II. However, there was a tendency among highly fearful patients according to the DAQ to report lower levels of discomfort during Period II, mean 2.6 (SD = 2.5) vs. mean 2.1 (SD = 3.0) (p = .078). When comparing genders, no statistically significant differences between the two periods were observed. When comparing subgroups, patients expecting dental treatment (as opposed to examination only) reported more discomfort post treatment in Period I (mean = 1.1, SD = 1.6) than in Period II (mean = 0.9, SD = 1.4) (p = .033). There were no statistically significant interaction effects between discomfort and the different subgroups. However, the interaction effect between discomfort and expected dental treatment was close to significance (p = .068).

Pain

There was no statistically significant difference in patients’ self-assessed pain between Period I and Period II (). When self-reported pain was compared between Period I and II within the subgroups dental fear, gender, and reason for dental treatment, patients with low fear according to the IDAF-4C reported significantly more pain in Period I (mean = 1.8, SD = 2.1) compared with Period II (mean = 1.4, SD = 2.0) (p = .014). Patients who were expecting dental treatment reported significantly more pain in Period I (mean = 1.3, SD = 1.8) than in Period II (mean = 1.1, SD = 1.6) (p = .016). There were no statistically significant interaction effects between pain and the different subgroups.

Tension

Patients in Period I were significantly more tense than patients in Period II (). When comparing self-reported tension within the subgroups in Period I and II, female patients reported higher levels in Period I (mean = 2.4, SD = 2.8) than in Period II (mean = 2.0, SD = 2.5) (p = .028). Patients who were expecting dental treatment reported significantly more tension in Period I (mean = 2.0, SD = 2.5) than in Period II (mean = 1.7, SD = 2.2) (p = .012). There were no statistically significant interaction effects between tension and the different subgroups. However, the interaction effect between tension and gender was close to significance (p = .067).

Patient satisfaction with dental health professionals

Total patient satisfaction did not differ significantly between Period I and Period II, nor did satisfaction with interpersonal skills. However, the patient group treated according to the DFCM (Period II) reported close to significantly greater satisfaction with the professionals’ qualities compared with the patient group receiving conventional treatment (Period I) (). A comparison of patient satisfaction (total, interpersonal, professional) within the subgroups revealed no statistically significant differences between Period I and II. There were no statistically significant interaction effects between patient satisfaction and the different subgroups.

Discussion

The scope of this paper was to study the Jönköping DFCM from a patient perspective. The perspective on the DFCM of dental health professionals has been reported on in a previous article, based on data originating from the same project [Citation30]. In this study, we compared two groups of patients, one of them receiving a conventional treatment regime, while the treatment of the other group was guided by the DFCM. The outcome variables were patient reports of discomfort, pain, tension, and patient satisfaction with their health professionals. The hypothesis was that using the Jönköping DFCM would result in patients reporting less discomfort, pain, tension, and greater satisfaction with dental health professionals. The hypothesis was somewhat supported by the results; patients reported less tension in Period II compared with Period I. However, such effects were not shown for the other outcomes, discomfort and pain. Interestingly, patients reported significantly less discomfort, pain and tension in the sub-analyses of patients who expected dental treatment in Period II (DFCM treatment), compared with Period I (conventional treatment). Female patients were significantly more tense, and patients with low levels of dental fear experienced more pain in Period I than in Period II. Although the results were significant, the effects were small. In a British study by Dailey et al. [Citation39], a similar intervention was performed. Even though other outcome measures than in the present study were used, the differences between the intervention and control groups were clearly significant. The reason why the results in the two studies differ is possibly due to more fearful patients in the British than in the present study, thus leaving greater scope for fear reduction with less of a floor effect, compared with the present study.

Female patients and younger patients in the present intervention study reported higher levels of dental fear compared with male or older patients. These results confirm previous knowledge reported from epidemiological studies [Citation2–4]. Moreover, female patients seem to draw greater benefit from the DFCM than men, as their tension levels were reduced in Period II compared with Period I. Armfield and Ketting [Citation28] suggested that improved communication skills and realistic information from dental health professionals would give patients a better understanding of their dental status and perceived treatment need. Based on the authors’ discussion [Citation28], patients in the present study might be expected to be more satisfied with the professionals’ interpersonal qualities in Period II; however, this was not shown in our study. Nevertheless, patient satisfaction with the dentist’s and dental hygienist’s professional qualities, measured with the patient attitude scale, was somewhat greater, close to significance, in Period II.

There were different patients in Periods I and II. Patients who participated in Period I were excluded from Period II. All patients were informed about the study, but did not know if they participated in Period 1 or 2; that is, whether the health professionals were trained in and treated them according to the DFCM or not.

The study samples in the intervention group were comparable with regard to age and gender in Period I and II; however, not with regard to dental fear and the reason for the dental visit where the fear level and awareness were higher in Period I. We can only speculate as to why these differences appear. There may have been differences in how patients were asked to participate; more patients, irrespective of dental fear status, were included in Period II than in Period I, since exclusion and non-participation rates were higher in Period I. It is possible that the patients in Period I were more aware of which treatment they were going to receive because their higher fear levels made them more alert as to what would happen at the visit compared with patients in Period II.

There were some shortcomings to the study: (1) Analyses of dropouts are missing and, for this reason, we cannot conclude anything about the representativeness of the study samples; (2) As shown in , there were more missing data in Period I than in Period II. This may be explained by the way the questionnaires were administered: pen and paper self-ratings in Period I and electronic self-assessments in Period II. However, since the effects are relatively small, we cannot conclude that the selection was biased. In our view, the administration routines did not jeopardize the results of this study; (3) The effect sizes for the statistically significant results (p < .05), according to Cohen [Citation40], are small and do not exceed 0.2. Whether the small differences between Period I and II are of practical relevance should be investigated in further studies.

Since it is primarily a financial question whether the DFCM should be introduced in clinical practice on a larger scale, there is a need for further studies of its usefulness and qualities, both from the patients’ and the health professionals’ point of view. As suggested in a previous study [Citation30], the time required for seeing new patients need not be longer if a simplified version of the DFCM is used in clinical practice.

As far as we know, there are no previously published studies on interventions for the purpose of reducing dental fear among patients with lower fear levels than dental phobia. The DFCM was studied within the Public Dental Service; i.e. in a general practice setting, where the model could be expected to have the greatest impact.

The Jönköping DFCM has several positive effects on adult patients in routine dental care. In a Swedish context, the differences between standard care and treatment according to the model were small but, in part, statistically significant. However, it is important to evaluate the model in further studies to allow generalization to other settings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank specialist psychologist and psychotherapist Nina Bengtsson for her great contribution to the DFCM training program. Also, special thanks to Folktandvården (the Swedish Public Dental Service) and Region Jönköping County for supporting the study, and to Lena Urge, Klara Köllerström, Ann-Christin Segerfeldt Böhlin, and Linda Andersson for making up the excellent research study staff. Further, many thanks to Birgitta Ahlström for her layout contribution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Oosterink FM, de Jongh A, Hoogstraten J. Prevalence of dental fear and phobia relative to other fear and phobia subtypes. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:135–143.

- Svensson L, Hakeberg M, UW B. Dental anxiety, concomitant factors and change in prevalence over 50 years. Community Dent Health. 2016;33:121–126.

- Liinavuori A, Tolvanen M, Pohjola V, et al. Changes in dental fear among Finnish adults: a national survey. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:128–134.

- Humphris G, Crawford JR, Hill K, et al. UK population norms for the modified dental anxiety scale with percentile calculator: adult dental health survey 2009 results. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13:29.

- Armfield JM. The extent and nature of dental fear and phobia in Australia. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:368–377.

- Smith TA, Heaton LJ. Fear of dental care: are we making any progress? J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1101–1108.

- Norderyd O, Kochi G, Papias A, et al. Oral health of individuals aged 3-80 years in Jönköping, Sweden, during 40 years (1973-2013). I. Review of findings on oral care habits and knowledge of oral health. Swed Dent J. 2015;39:57–68.

- Armfield JM. Towards a better understanding of dental anxiety and fear: cognitions vs. experiences. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:259–264.

- Thomson WM, Poulton RG, Kruger E, et al. Changes in self-reported dental anxiety in New Zealand adolescents from ages 15 to 18 years. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1287–1291.

- Hägglin C, Berggren U, Hakeberg M, et al. Variations in dental anxiety among middle-aged and elderly women in Sweden: a longitudinal study between 1968 and 1996. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1655–1661.

- Klepac RK, Dowling J, Hauge G. Characteristics of clients seeking therapy for the reduction of dental avoidance: reactions to pain. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1982;13:293–300.

- Berggren U, Meynert G. Dental fear and avoidance: causes, symptoms, and consequences. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:247–251.

- Armfield JM. What goes around comes around: revisiting the hypothesized vicious cycle of dental fear and avoidance. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:279–287.

- Armfield JM, Stewart JF, Spencer AJ. The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7:1.

- Vassend O. Anxiety, pain and discomfort associated with dental treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:659–666.

- Cohen SM, Fiske J, Newton JT. The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. Br Dent J. 2000;189:385–390.

- Tracey I, Mantyh PW. The cerebral signature for pain perception and its modulation. Neuron. 2007;55:377–391.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994.

- Klages U, Kianifard S, Ulusoy O, et al. Anxiety sensitivity as predictor of pain in patients undergoing restorative dental procedures. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:139–145.

- Locker D, Shapiro D, Liddell A. Negative dental experiences and their relationship to dental anxiety. Community Dent Health. 1996;13:86–92.

- van Wijk A, Lindeboom JA, de Jongh A, et al. Pain related to mandibular block injections and its relationship with anxiety and previous experiences with dental anesthetics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:S114–S119.

- Sanikop S, Agrawal P, Patil S. Relationship between dental anxiety and pain perception during scaling. J Oral Sci. 2011;53:341–348.

- Kyle BN, McNeil DW, Weaver B, et al. Recall of dental pain and anxiety in a cohort of oral surgery patients. J Dent Res. 2016;95:629–634.

- Ståhlnacke K, Söderfeldt B, Unell L, et al. Patient satisfaction with dental care in one Swedish age cohort. Part II–What affects satisfaction. Swed Dent J. 2007;31:137–146.

- Ståhlnacke K, Söderfeldt B, Unell L, et al. Patient satisfaction with dental care in one Swedish age cohort. Part 1-descriptions and dimensions. Swed Dent J. 2007;31:103–111.

- Oosterink FM, de Jongh A, Aartman IH. What are people afraid of during dental treatment? Anxiety-provoking capacity of 67 stimuli characteristic of the dental setting. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:44–51.

- Humphris G, King K. The prevalence of dental anxiety across previous distressing experiences. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:232–236.

- Armfield JM, Ketting M. Predictors of dental avoidance among Australian adults with different levels of dental anxiety. Health Psychol. 2015;34:929–940.

- Skaret E, Öst L-G. Cognitive behavioral therapy for dental phobia and anxiety. Chichester: Wiley; 2013. Available from: http://www.books.google.se/.

- Brahm CO, Lundgren J, Carlsson SG, et al. Development and evaluation of the Jönköping dental fear coping model: a health professional perspective. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;76:320–330.

- Milgrom P, Weinstein P, Getz T. Treating fearful dental patients: a patient management handbook. 2nd ed. Seattle (WA): University of Washington; 1995.

- Skaret E, Weinstein P, Kvale G, et al. An intervention program to reduce dental avoidance behaviour among adolescents: a pilot study. Eur J Paediatr Dentistry. 2003;4:191–196.

- Søvdsnes EK, Skaret E, Espelid I, et al. Interaktiv nettside for endring av helseatferd. Den Norske Tannlegeforenings Tidende. 2010;120:456–462.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 1991.

- Neverlien PO. Assessment of a single-item dental anxiety question. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:365–369.

- Armfield JM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the INDEX of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C+). Psychol Assess. 2010;22:279–287.

- Wide Boman U, Armfield JM, Carlsson SG, et al. Translation and psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C) (+)). Eur J Oral Sci. 2015;123:453–459.

- Gale EN, Carlsson SG, Eriksson A, et al. Effects of dentists' behavior on patients' attitudes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:444–446.

- Dailey YM, Humphris GM, Lennon MA. Reducing patients' state anxiety in general dental practice: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res. 2002;81:319–322.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge; 1988.