Abstract

Objective

To identify common resilience factors against non-communicable diseases (dental caries, diabetes type II, obesity and cardiovascular disease) among healthy individuals exposed to chronic adversity.

Materials and methods

The databases MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus and CINAHL were searched. Observational studies in English assessing resilience factors among populations living in chronic adversity were included. Intervention studies, systematic reviews, non-original articles and qualitative studies were excluded. There were no restrictions regarding publication year or age. No meta-analysis could be done. Quality assessments were made with the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS).

Results

A final total of 41 studies were included in this systematic review. The investigated health resilience factors were divided into the following domains: environmental (community and family) and individual (behavioural and psychosocial). A narrative synthesis of the results was made according to the domains.

Conclusions

Individual psychosocial, family and environmental factors play a role as health resilience factors in populations living in chronic adversity. However, the inconclusive results suggest that these factors do not act in isolation but interplay in a complex manner and that their interaction may vary during the life course, in different contexts, and over time.

Introduction

Dental caries is the most common non-communicable disease (NCD) [Citation1]. There are around 2.4 billion people with untreated caries in the permanent dentition [Citation2] with consequences such as pain, infections, lost working and school days, and difficulties to eat and speak as well as negative impacts on well-being and quality of life [Citation3]. A high intake of sugar contributes to a poor diet, which is a common risk factor for the NCDs dental caries, diabetes, overweight and cardiovascular disease [Citation4]. The complications of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases include heart attack, stroke and blindness, and the risk of other NCDs is increased by obesity [Citation5]. NCDs have adverse effects on health and vulnerable populations have the highest level of illness [Citation6].

The unequal distribution in health can be seen both within and between countries, following a social gradient with worse health outcomes among populations with lower socioeconomic position [Citation6]. These health disparities are also seen in populations such as ethnic groups [Citation6,Citation7], indigenous and minority groups [Citation6,Citation8], refugees and immigrants, homeless, and those lacking social protection such as health care [Citation9]. Chronic adversity refers to hardships that extend over a significant amount of time and has a persistent impact on the individual, such as poverty [Citation10]. People living in chronic adversity have higher risk of developing chronic disease due to psychosocial stress, higher levels of risk behaviour, unhealthy living conditions and limited access to health care [Citation11,Citation12]. The risk can be multiplied if there is exposure to several disadvantage factors [Citation13]. Chronic adversity is a dynamic state that can change during the life course in interaction with the environment, life changes and transitions [Citation13].

Recognizing that some individuals are less predisposed to health problems by biological endowment, we proceed to investigate determinants among individual and environmental factors [Citation14,Citation15]. These factors may allow some individuals to adapt positively and cope in the face of significant adversity and express better health outcomes – so-called resilience [Citation16,Citation17]. Resilience can be defined in various ways. Luthar et al. defined resilience as ‘a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity’ [Citation15]. Individuals exhibiting higher levels of resilience also present with better quality of life and health-promotive behaviour [Citation18].

Resilience can be expressed both as a process and an outcome. To distinguish between them, the term resilience is used to describe the process mediating the relationship between chronic adversity and the outcome, whereas resilient is used to describe the outcome, e.g. a resilient individual [Citation10]. When faced with adversity, individuals who have a coping capacity can maintain and develop health. Concepts such as optimism, hardiness, adaptation, coping, sense of coherence (SOC) and self-efficacy can fit in a group of resources or assets that play a key role in the resilience process [Citation19]. Resilience can be considered in multiple levels – individual, group, community – and the social and cultural context are important [Citation19].

A common risk factor approach takes several chronic diseases into account and considers the wider socio-environmental factors [Citation20]. Instead of attempting to prevent one disease at the time, by applying a common risk approach, prevention of a risk factor can have impact on several diseases. By shifting to a salutogenic perspective, studies on common resilience factors can give us important knowledge to be used in health promotion with an integrated approach across diseases. Taking a starting point from the interrelationship between oral health and general health, this study will apply a common resilience approach – better health outcomes may be achieved by common health factors giving results on several NCDs. Strengthening the availability of assets and resources and the ability to use them is an essential part of health promotion. Therefore, studies on resilience factors may contribute to a deeper understanding of health assets and is important knowledge to be used in health promotion [Citation16].

To our knowledge, no prior study has systematically reviewed health resilience factors among populations living in chronic adversity. Therefore, this systematic review aims to identify common resilience factors against NCDs (dental caries, diabetes type II, obesity and cardiovascular disease) among healthy individuals exposed to chronic adversity.

Materials and methods

Protocol development and registration

The protocol of this systematic review has been registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register Of Systematic Reviews), ID number CRD42019127002. This systematic review is reported according to PRISMA guidelines (the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement) [Citation21].

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review included observational studies written in English assessing resilience factors among populations living in chronic adversity (see ). Chronic adversity in this article is defined according to the exposures stated in . This systematic review explores potential resilience factors by using a search string including concepts of assets and resources closely related to resilience [Citation19]. Intervention studies, systematic reviews, non-original articles and qualitative studies were excluded, as well as studies using other definitions as exposure of chronic adversity. There were no restrictions regarding publication year or age.

Table 1. Key words and key terms to describe PECOS: the Population (P), Exposure (E), Comparison (C), Outcome (O) and Study design (S).

Information sources

The databases MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus and CINAHL were searched on 7 March 2019 and a complete update was done on 23 March 2022. Supplementary approaches to identify additional studies included conducting hand searches and checking reference lists.

Search

Key words and terms to describe the Population (P), Exposure (E), Comparison (C), Outcome (O) and Study design (S) were combined with the Boolean operators AND and OR (see ). The search strategy was peer reviewed by the research team and a librarian. A full search strategy of each database is available in the supplementary information (Appendix 1).

Study selection

All identified papers were screened dually and independently according to title and abstract by two authors (MN and PC or AHL). Then, full-text articles were retrieved and screened dually and individually for eligibility according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles were excluded if it was impossible to extract data on the target outcome measures. Disagreements were solved between the authors. A list of excluded full-text articles can be found in the supplementary information (Appendix 2).

Data collection process and data items

A piloted data extraction form was used for data collection. The data were extracted in duplicate by two authors independently (MN and PC or AHL) and included the following information: author, year, study design, country, population, health definition, exposure, resilience factor investigated, and results. Odds ratios and risk ratios were extracted when possible. For continuous outcomes, p values for difference in means were extracted. Due to lack of data, it was not possible to reverse odds ratios to ensure alignment across studies. In addition, values below one will not be consistent in representing health resilience.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Quality assessment was done according to a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) [Citation26,Citation27], which assesses quality in several domains: sample representativeness and size, comparability, ascertainment of exposure and outcome, and statistical quality. The scales were modified to fit the research question by adding an item on resilience factors. The scale for cohorts was modified for longitudinal studies by removing an item on un-exposed cohort. The modified NOS scale is available in the supplementary information (Appendixes 3 and 4). Calibration exercise was done by the authors. Quality assessment was completed dually and individually by two authors (MN and PC or AHL). Any differences were resolved by comparing standardized scores followed by a consensus or by consulting a third author.

Studies could receive a maximum score of 12 for cross-sectional studies and 10 for longitudinal studies. Cross-sectional studies with a score of 10–12 were considered high quality, 7–9 were considered moderate, and 0–6 were low quality; for longitudinal studies, the corresponding cut-offs were 9–10, 6–8 and 0–5.

Results

Study selection

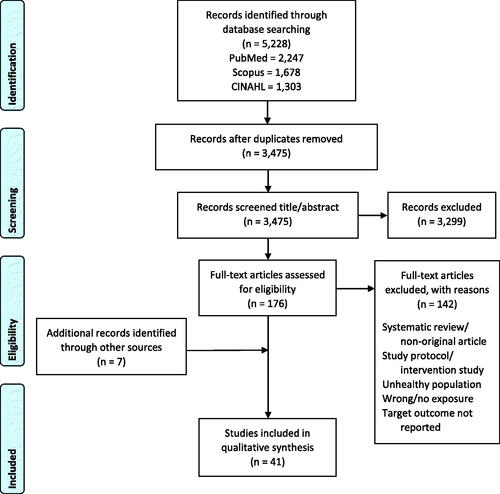

The initial search identified 5,228 references. After the exclusion of duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, we screened 176 full text articles for eligibility. Of them, a total of 34 articles were included. We identified seven additional articles by hand search and in reference lists. A final total of 41 studies were included in this systematic review (see the PRISMA flowchart in ).

Study characteristics

This review includes 11 longitudinal and 30 cross-sectional studies. Its key findings are presented in a Summary of Findings table (Appendix 5). Of the 41 included studies, 28 considered the health domain obesity, eight dental caries, seven cardiovascular disease and one diabetes. The studies were predominantly from the United States (n = 25). Seven of the articles were based on the same study in Australia [Citation28–34]. Other countries included Albania [Citation35], Canada [Citation35], Brazil [Citation35,Citation36], Colombia [Citation37], Haiti [Citation38], Israel [Citation39], New Zealand [Citation40], South Africa [Citation41] and West Germany [Citation42]. The studies were published between 1990 and 2022. The longitudinal studies had between 1 and 14 years of follow-up. The sample sizes in the studies ranged from 36 to 5,366. Study populations in most studies were exposed to chronic adversity based on individual income or educational level or neighbourhood socioeconomic status.

Quality assessment

Of the 11 included longitudinal studies, two were considered low quality, eight moderate quality and one high quality. Six cross-sectional studies were evaluated as low quality, 22 as moderate quality and two as high quality. See the Summary of Findings table in the supplementary information (Appendix 5).

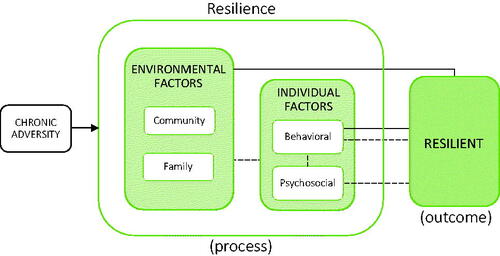

Qualitative synthesis of results

No meta-analysis was possible due to large variety in measurement of resilience factors and the heterogeneity of the data. See the Summary of Findings table in the supplementary information for results from specific studies (Appendix 5). The results from the 41 studies included in this systematic review were compiled and outlined in a conceptual model (see ). In this model, the investigated health resilience factors were divided into the following domains: environmental (community and family) and individual (behavioural and psychosocial). These domains determined our narrative synthesis of the results.

Figure 2. Conceptual model of how individuals exposed to chronic adversity, through resilience (process), can express health and be resilient (outcome). The resilience factors investigated in the included studies are categorized by domains.

Our conceptual model was guided by Moor et al. [Citation43] and Dahlgren and Whitehead [Citation44]. In the ‘conceptual model for explaining social inequalities’ by Moor et al. [Citation43], socioeconomic differences in self-rated health can be explained by the direct and indirect contribution of material/structural, psychosocial and behavioural factors. We have used the terms environmental, psychosocial and behavioural factors to describe the relationship between chronic adversity and being resilient. It should be noted that causality may run in both directions. According to Dahlgren and Whitehead’s model ‘Main determinants of health’, the main influences on health can be divided into four layers: first, the individual; second, family, friends and the local community; third, the living and working environment; and finally, the general structural environment [Citation44].

Results of individual studies

Environmental factors

Objective and subjective neighbourhood environment

Five studies investigated associations with objective neighbourhood environmental factors and two with subjective factors, such as availability of fast food outlets, availability of fruits and vegetables, and safety and found no significant results [Citation29–31,Citation38,Citation45,Citation46]. Availability of healthy and unhealthy food at home showed both significant [Citation32,Citation46] and non-significant results [Citation46]. Receiving health information from newspapers was significantly associated with health (OR 7.31, p=.01), but receiving health information from magazines was not [Citation47].

Social environment

Social environmental factors include the social context in which people live and interact. Adult women having social capital (OR 0.59, p=.0001), network (OR 0.75, p=.017), intra-community trust and solidarity (OR 0.78, p=.004) and collective action (OR 0.38, p=.043) were less likely to have hypertension. However, solidarity, communication, community empowerment and social inclusion were not significantly associated with health outcomes in the same sample [Citation38]. One study found that living alone was health protective among adults (PR 2.31, p<.05) [Citation45]; however, one study showed no significant associations with having eating partners at home [Citation41].

Further, a study among elders showed that negative interaction was not significantly associated with risk of heart disease at baseline, but it was significantly associated after four years and six years (p<.0001) [Citation48]. Adolescents not attending church had lower BMI values (p=.01) [Citation40]. Social support was health protective for oral health in adults [Citation46], but caregivers having social support was not significantly associated with oral health in children [Citation49]. The social norms for physical activity and eating were not significantly associated with weight status in children [Citation30].

Family support

Six articles studied factors related to family support. Four of them found significant results. Healthy outcomes were significantly associated with higher caregiver monitoring and supervision of exercise in adolescents (OR 5.746, p=.013) [Citation50], with families having a strong parent–child connection and parental coping [Citation51], with regulated family meals or social eating [Citation46] and with families often eating healthy food together (OR 1.28, p<.0005) [Citation32]. However, they had no significant association with having parental social support for physical activity in children [Citation30], parent relation [Citation37] and being discouraged by family from sitting around or from eating unhealthy foods [Citation32].

Peer support and school

Friends engaging in supportive behaviour for healthy eating was associated with weight resilience among adolescents aged 12–17 years (OR 0.656, p=.035) [Citation50]. On the other hand, having friend support or a positive school environment was not significantly associated with weight status in a sample of children 10–14 years [Citation37].

Work environment

One longitudinal study investigated protective factors within the work environment [Citation42]. Adults who had a lower level of exhaustive coping, that is, continued efforts and associated negative feelings, had absence of heart disease to a larger degree than those with higher levels (OR 4.53, p<.05). Health was also associated with status consistency, namely, having an occupational grade in line with the educational background (OR 4.40, p<.05). No associations were found with job insecurity, work pressure or promotion prospects.

Behavioural factors

Oral health-related behaviours, physical activity and dietary habits

Fourteen studies examined the direct association of behaviours with health outcomes. For instance, one study found association between a caries-free status and caregivers adhering to the recommended oral health-related behaviours of their children (p=.0004) [Citation52]. Investigations of association between health and engagement in physical activity or screen time showed both significant [Citation28,Citation37] and non-significant results [Citation37,Citation39,Citation47,Citation41,Citation53].

Having healthier dietary habits was associated with healthier outcomes in three studies among adults [Citation28,Citation45], but not in three other studies [Citation47,Citation41,Citation54]. In contrast, making less healthy food choice was associated with healthy weight status in children [Citation39,Citation55] and adults [Citation41]. Mindless eating among adults [Citation46] and type of food per week among children [Citation39] had no significant health associations. Neither did adolescents’ cooking methods [Citation56]; however, caregivers’ preparation methods were significantly associated with healthy weight status in one study (OR 0.86, p<.01) [Citation56], but not in another study [Citation57]. Weight control practice was not associated with health outcomes in two studies [Citation55,Citation58], but was significant in one longitudinal study (OR 1.09, p<.000) [Citation54].

Food acquisition and intentions

Five studies examined food acquisition patterns and intentions regarding dietary habits. Adolescents shopping in full-service grocery stores had healthier outcomes (OR 5.147, p=.033) [Citation50], but no health association was seen with caregivers’ food acquisition patterns [Citation57,Citation59]. Conversely, caregivers with lower intentions of healthier eating had higher odds of their children having healthy weight (OR 1.15, p=.02) [Citation59]. The same association could be seen in a longitudinal study among adults (OR 1.05, p<.000) [Citation54]. Two other studies showed no associations between health outcomes and food behavioural intentions in youth or caregivers [Citation56,Citation57].

Psychosocial factors

Knowledge

Eleven studies investigated knowledge as a health-protective factor. More caregiver knowledge showed significantly healthier outcomes in three studies including small children up to five years old [Citation49,Citation52,Citation60], but contrary results were seen in one study on caregivers of children aged 3–4 years [Citation61]. However, no health association was seen with caregivers of children aged 1–3 years [Citation49] or in four studies on families with adolescents aged approximately 10–14 years [Citation55–57,Citation59]. Among adults, two studies found no associations [Citation45,Citation47], whereas one study showed significant association between knowledge and health outcomes [Citation46].

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was assessed in 14 studies using 22 variables, showing inconsistent results. Two maternal self-efficacy factors were protective [Citation30,Citation39], but seven variables regarding maternal self-efficacy showed no significant results [Citation30,Citation49,Citation52,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation60]. Self-efficacy was associated with health outcomes neither among adolescents [Citation37,Citation55,Citation56] nor adults [Citation39,Citation45,Citation58]. Four studies conversely showed an association between lower efficacy and healthier outcomes [Citation50,Citation54,Citation55,Citation58]. On the other hand, personal decision-making ability (OR 0.41, p=.021) [Citation38] and self-efficacy for healthy eating and oral hygiene habits [Citation46] was found to be health protective among adults. Further, the ability to make time for healthy eating and for physical activity was a significantly protective factor (OR 1.34, p<.0005 and OR 1.11, p=.016, respectively) [Citation32].

Sense of coherence

Three studies investigated associations between health outcomes and SOC. Higher caregivers’ SOC [Citation52] as well as children’s SOC (RR 0.70, p<.05) [Citation36] was protective; however, family’s SOC showed no significant associations [Citation62].

Locus of control and fatalism

One study showed positive associations between higher caregiver internal locus of control and child health outcomes [Citation52]. However, concerning fatalistic beliefs, two studies showed they have no significant associations with health outcomes [Citation47,Citation63]. In terms of oral health, not believing that most children will eventually develop caries was associated with lower disease severity (p<.05) [Citation60] in children aged 4–5 years (OR 2.67 p<.05) but not in those aged 1–3 [Citation49].

Striving and John Henryism

Three studies investigated the effect of striving or John Henryism [Citation35,Citation64,Citation65], all showing negative associations; namely, having lower levels of striving was health protective. However, in two of the studies, this association could only be seen in a subsample [Citation35,Citation65].

Physical and psychological health

Four studies showed positive associations between better health outcomes and caregiver health status – including healthy weight status (OR 0.790, p=.027) [Citation50]; (OR 4.04, p=.003) in [Citation59], less poor sleep [Citation42], and physical well-being [Citation37]. However, other studies found no association between health outcomes and psychological well-being [Citation37,Citation49] or child prosocial behaviour [Citation39]. Child behaviour difficulties were associated with health status, but only in a subsample (OR 1.09, p<.05) [Citation39].

Rewards and rules (positive reinforcement)

Caregivers giving rewards or punishment for different behaviours was not associated with health outcomes in children [Citation30,Citation50]; however, setting parental rules to limit sedentary behaviours was associated with resilience to unhealthy weight gain in children aged 5–12 years (OR 1.14, p=.013) [Citation30]. Children having stronger self-regulatory behaviour by being able to delay gratification had lower BMI at follow up [Citation66]. Mothers allowing their children to eat whenever they want to was associated with children’s health status, but only in a subsample (OR 0.69, p<.05) [Citation39].

Self-concept

Six of the included studies have investigated self-image in relation to health status. Caregivers being satisfied with their body image were associated with healthy weight status in the family (OR 0.51, p<.05) [Citation57]. There was an association between body weight status in adults and level of self-concept [Citation58] as well as self-reported body silhouette size (OR 2.78, p=.02) [Citation47]. Self-classified BMI category or feeling at ideal body weight was not associated with body weight status [Citation47]. Selecting a smaller ideal body figure was a health protective factor in girls (OR 6.71, p<.05) but not in boys [Citation55]. The perception of discrimination was not significantly associated with health outcomes [Citation52]. Excellent or very good self-rated health was associated with lower BMI (OR 0.93, p<.000) [Citation54].

Attitudes and beliefs

There were nine studies examining different attitudes and beliefs as health protective factors. Attitude to physical exercise was associated with weight status in children, but only in boys (p=.01) [Citation53], and it was not associated with health status in adults [Citation47]. Intrinsic motivation was associated with normal weight status in children (p<.001) [Citation37]. Further, health outcomes were not significantly associated with controlling or losing weight as a reason to exercise [Citation47] or committing to self-care related to healthy eating [Citation32]. The importance of engaging in oral health behaviours was reported to a higher degree by parents of caries-free children; however, neither the perceived seriousness of the disease nor the benefits of health-oriented behaviour were significantly health protective in the sample [Citation52], nor was the importance of doing physical activity as a family [Citation30].

Examination of perceptions on food such as affordability, convenience, importance and taste only showed association between convenience and healthy weight status in the family (OR 0.43, p<.05) [Citation57]. Regarding barriers, caregiver perceived susceptibility and barriers to recommended health behaviours were associated with healthier outcomes in children [Citation52]. Moreover, not experiencing barriers related to waste in fruit and vegetable intake was health protective (PR 0.29, p<.05); however, barriers related to time and cost [Citation45] and having a healthy eating attitude [Citation46] had no significant association.

Stress and coping

Eleven of the included articles examined the effect of stress and the ability to cope with stress. Among adults, lower levels of perceived stress significantly associated with healthier outcomes in two studies [Citation33,Citation34], but two studies found no associations [Citation58,Citation67]. Not eating in response to emotions was associated with better health [Citation46]. Further, a lower amount of distress among caregivers was associated with better health outcomes in one study on children [Citation52] and one study on adolescents (OR 0.796, p=.048) [Citation50]. However, four studies showed no significant association between health and caregiver stress [Citation34,Citation49,Citation52,Citation67], and two conversely showed an association between more caregiver life stress and better health outcomes (OR 0.62, p<.05) [Citation49,Citation61]. In one article, lower maternal resilience (i.e. resilience in stress situations) was associated with better health, but only in a subsample (OR 1.07, p<.05) [Citation39]. Moreover, having shift-and-persist strategies (i.e. accepting and adapting to stress while having optimism) was protective in children [Citation68].

Compiled measures

Five articles utilized compiled measures based on a number of protective factors, and all of them were significantly associated with healthier outcomes [Citation28,Citation61,Citation63,Citation69,Citation70]. However, cumulative risk, which is a compiled measure of nine risk factors, was not significantly associated with better health [Citation66].

Discussion

Key findings

This systematic review of observational studies aimed to identify common protective factors against chronic diseases among populations exposed to chronic adversity. Our findings revealed few consistent results in the studies. Although the current available evidence is weak, the findings indicate that individual psychosocial, family and environmental factors act as health resilience factors in populations living in chronic adversity. However, the inconclusive results suggest that these factors do not act in isolation; rather, they interplay in a complex manner and their interaction may vary during the life course [Citation71,Citation72], in different contexts [Citation73], and over time [Citation14].

Resilience and salutogenesis share many similarities. Resilience research focus on coping in individuals and groups in chronic adversity whereas salutogenic research tries to explain coping in all people. Resilience and the salutogenic concept SOC can both be considered assets important for well-being [Citation19]. As in our systematic review, several previous studies have shown that SOC is related to better oral health outcomes for children, adolescents and adults [Citation74–77]. In addition, a stronger SOC is related to healthier behaviours such as tooth brushing and dietary habits [Citation78]. SOC emerges from different life experiences, and it is mainly developed during childhood, adolescence and early adulthood [Citation79] and tends to increase with age over the whole life span [Citation80]. SOC is related to other psychosocial factors and overlaps with other resources [Citation81]. Thus, knowledge of the factors that can develop and promote a strong SOC could give us deeper insight into health promotive mechanisms.

According to a previous systematic review, the family and school context are relevant for the development of SOC among adolescents – for example, through offering support, encouragement and a positive climate [Citation82]. Regarding the social environment, our systematic review shows that peer support may be health protective for adolescents but not for children, which is in line with a previous systematic review [Citation74]. This suggests that for children the importance of the social environment lies mainly within the family but that the external environment (school and friends) gains importance during adolescence [Citation14,Citation83,Citation84].

The studies on family factors included in this systematic review showed inconclusive results. Only four of six studies showed significant associations with health outcomes. However, a systematic review among refugee children showed the importance of family support [Citation85], and several previous qualitative studies highlighted the importance of family [Citation83,Citation84,Citation86]. Perhaps family factors act indirectly, mediated through values and attitudes that are transmitted from parents during upbringing – values and attitudes that will affect behaviour and health later in life [Citation84]. Longitudinal studies with a longer follow-up time could possibly give more insight into the role of the family as a resilience factor.

In this systematic review, knowledge appears to be of importance for caregivers with smaller children, but not for caregivers of other age groups. A previous systematic review showed that higher knowledge levels were significantly associated with lower caries levels among children [Citation87]. However, perhaps knowledge in itself is not enough as a resilience factor of other age groups. In a study among adolescents, knowledge was seen as important for making healthy choices but did not lead to healthy choices in itself since personal incentives and motivation were also required [Citation84]. Our review indicates that knowledge may act together with attitude as health promotive, for instance, when individuals have intrinsic motivation and finding engaging in health behaviours important [Citation37,Citation52].

Psychosocial factors are associated with health and health behaviours, both directly and in-directly [Citation43]. A systematic review on resilience among refugee children showed that self-esteem, social support, self-efficacy and prosocial behaviour were important individual protective factors [Citation85]. In a previous systematic review, parental locus of control was protective in adolescents [Citation74]. Our systematic review shows mixed results regarding most of the psychosocial factors and health related behaviours. Therefore, we find it unlikely that a single factor can solely explain complex health behaviours and the distal health outcomes selected for this systematic review. The inconsistent associations can be explained in several ways: flaws in study designs and methodological quality, inadequately defined psychosocial constructs, and lack of conceptual frameworks where confounders are accounted and adjusted for or where psychosocial factors act together.

The 11 articles examining stress indicated that lower levels of stress can act protective, but in two studies, higher levels of stress were associated with better health. Perhaps being able to accept and adapt to stress enables some individuals to cope with higher levels of stress and still express health [Citation68]. Several psychosocial factors may enable individuals to cope with stress. Factors such as locus of control and self-efficacy affect individual empowerment, which is the process of gaining control over one’s own life [Citation16]. Individuals with hardiness are able to deal with stress in life [Citation16]. Moreover, a positive social environment may buffer stress [Citation12]. All these factors increase the feeling of being in control, which enables individuals to handle stressful events in life [Citation16].

In this systematic review, none of the objective human-built environmental factors were associated with health. However, previous studies have highlighted the importance of a neighbourhood’s physical environment, such as food availability and walkability [Citation12].

Strengths and limitations

Due to the cross-sectional nature of most included studies, causal direction cannot be determined, and no conclusions can be drawn about causal relationships. Problems also include reverse causation and confounders. Causality may also run in both directions.

A main limitation was the methodological quality of the included studies. Only three of the studies were evaluated as high quality. The methodological issues that reduced the quality of the included studies were small sample sizes, non-representative samples, and not validated measures of exposure or outcome. Many of the included studies failed to show significant results, perhaps due to small sample sizes.

The definitions and measures applied in the included studies showed a considerable heterogeneity, which limited the possibility to pool study results in meta-analysis. Further, the included studies showed a mix of salutogenic approach and pathogenic approach; for instance, some measured health protective factors, whereas some absence of risk factors (i.e. a pathogenic focus). Many of the reviewed studies relied on well-studied, validated constructs and scales, such as SOC and self-efficacy, which means that other important resilience factors may have been overlooked.

This systematic review was limited to English studies. However, there was no limit to age or year. Most studies were made in high-income countries, such as the United States and Australia, and may not be applicable in other contexts. Not all results were possible to discuss due to the limited scope of this review.

Strengths include quality assessment using the tool NOS adapted to the research question. The included longitudinal studies were missing un-exposed groups, and we have adapted the quality assessment of cohorts to be able to apply it on longitudinal studies. The methodological quality of each included study was rated independently by two or more reviewers, which increases internal validity. In addition, the review is reported according to PRISMA guidelines.

There are several models from the social epidemiological field to explain health determinants. Most of them include factors that act directly and indirectly on the individual, family and environmental level. The conceptual model adapted in this systematic review was based on Moor et al. [Citation43] and Dahlgren and Whitehead [Citation44], whose work we consider to be well-known, multi-dimensional and comprehensive. According to our model, healthy behaviours were included as resilience factors, but they could also be considered a proxy measure of the resilience factors that shape the habits.

Conclusions

This systematic review has assessed resilience factors across several domains. While the findings were inconsistent, the results in the reviewed studies indicate that individual, family and environmental factors can act as health resilience factors. A holistic approach needs to be considered, applying a common integrative approach on both risk and resilience factors across diseases in health promotive efforts at all stages of life, especially critical periods. Future systematic reviews using a stronger conceptual definition and narrower focus could give clearer insight into possible health resilience factors. In future research, qualitative studies could give more in-depth insights into resilience factors and provide an understanding of health promotive mechanisms among healthy individuals living in chronic adversity.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to formulating the idea and designing the study. MN contributed to literature search, data extraction, quality assessment of the included studies and drafted the manuscript. AHL and PC contributed to the data extraction and quality assessment of the included studies. All authors interpreted the results and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

5_Summary_of_findings_table_220610.docx

Download MS Word (122.2 KB)4_Newcastle_Ottawa_longitudinal_studies_modified_220610.docx

Download MS Word (25.2 KB)3_Newcastle_Ottawa_crossectional_modified_220610.docx

Download MS Word (27.8 KB)2_List_of_excluded_studies_with_reasons_for_exclusion_220610.docx

Download MS Word (218.8 KB)1_Database_search_strategy_220610.docx

Download MS Word (19.8 KB)Acknowledgements

Systematic review registration number: PROSPERO ID number CRD42019127002.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Schwendicke F, Dörfer CE, Schlattmann P, et al. Socioeconomic inequality and caries. J Dent Res. 2015;94(1):10–18.

- Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of untreated caries. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650–658.

- Sheiham A. Oral health, general health and quality of life. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(9):644.

- WHO (World Health Organization). Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva; 2015.

- WHO (World Health Organization). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. Geneva; 2014.

- WHO (World Health Organization). Closing the gap in a generation health equity through action on the social determinants of health commission on social determinants of health. Geneva; 2008.

- Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):5–23.

- Laws R, Campbell KJ, van der Pligt P, et al. The impact of interventions to prevent obesity or improve obesity related behaviours in children (0–5 years) from socioeconomically disadvantaged and/or indigenous families: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):779.

- Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Social determinants of health. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Van Breda AD. A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Social Work. 2018;54(1):1–18.

- World Health Organization. Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. 182 p.

- Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):125–145.

- Aday LA. Health status of vulnerable populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15(1):487–509.

- Fisher-Owens SA, Gansky SA, Platt LJ, et al. Influences on children’s oral health: a conceptual model. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e510–e520.

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–562.

- Koelen MA, Lindström B. Making healthy choices easy choices: the role of empowerment. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(S1):S10–S16.

- Christmas CM, Khanlou N. Defining youth resilience: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2018;17(3):731–742.

- Fernanda Cal S, Ribeiro De Sá L, Glustak ME, et al. Resilience in chronic diseases: a systematic review. Cogent Psychol. 2015;2(1):1024928.

- Mittelmark MB. Resilience in the salutogenic model of health. In: Ungar M, editor. Multisystemic resilience: adaptation and transformation in contexts of change. New York: Oxford University Press; 2021. p. 153–164.

- Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(6):399–406.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Williams J, Allen L, Wickramasinghe K, et al. A systematic review of associations between non-communicable diseases and socioeconomic status within low- and lower-middle-income countries. J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):020409.

- Flaskerud JH, Winslow BJ. Conceptualizing vulnerable populations health-related research. Nurs Res. 1998;47(2):69–78.

- Pesantes MA, Lazo-Porras M, Abu Dabrh AM, et al. Resilience in vulnerable populations with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31(9):1180–1188.

- de Chesnay MA, Anderson B. Caring for the vulnerable: perspectives in nursing theory, practice and research. 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2008.

- Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis [Internet]; 2011. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, et al. Are healthcare workers intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–17.

- Ball K, Abbott G, Cleland V, et al. Resilience to obesity among socioeconomically disadvantaged women: the READI study. Int J Obes. 2012;36(6):855–865.

- Cleland V, Hume C, Crawford D, et al. Urban-rural comparison of weight status among women and children living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Med J Aust. 2010;192(3):137–140.

- Crawford D, Ball K, Cleland V, et al. Maternal efficacy and sedentary behavior rules predict child obesity resilience. BMC Obes. 2015;2(1):26.

- Lamb KE, Thornton LE, Olstad DL, et al. Associations between major chain fast-food outlet availability and change in body mass index: a longitudinal observational study of women from Victoria, Australia. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e016594.

- Macfarlane A, Abbott G, Crawford D, et al. Personal, social and environmental correlates of healthy weight status amongst mothers from socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods: findings from the READI study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:23.

- Mouchacca J, Abbott GR, Ball K. Associations between psychological stress, eating, physical activity, sedentary behaviours and body weight among women: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):828.

- Olstad DL, Ball K, Wright C, et al. Hair cortisol levels, perceived stress and body mass index in women and children living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods: the READI study. Stress. 2016;19(2):158–167.

- Gupta S, Belanger E, Phillips SP. Low socioeconomic status but resilient: panacea or double trouble? John Henryism in the International IMIAS Study of older adults. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2019;34(1):15–24.

- Tomazoni F, Vettore MV, Mendes FM, et al. The association between sense of coherence and dental caries in low social status schoolchildren. Caries Res. 2019;53(3):314–321.

- Olaya-Contreras P, Bastidas M, Arvidsson D. Colombian children with overweight and obesity need additional motivational support at school to perform health-enhancing physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(5):604–609.

- Malino C, Kershaw T, Angley M, et al. Social capital and hypertension in rural Haitian women. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(10):2253–2260.

- Soskolne V, Cohen-Dar M, Obeid S, et al. Risk and protective factors for child overweight/obesity among low socio-economic populations in Israel: a cross sectional study. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:456.

- Dewes O, Scragg R, Elley CR. The association between church attendance and obesity-related lifestyle behaviours among New Zealand adolescents from different Pacific Island ethnic groups. J Prim Health Care. 2013;5(4):290–300. Dec

- Mbhatsani HV, Mabapa NS, Ayuk TB, et al. Food security and related health risk among adults in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2021;117:11–12.

- Siegrist J, Peter R, Junge A, et al. Low status control, high effort at work and ischemic heart disease: prospective evidence from blue-collar men. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(10):1127–1134.

- Moor I, Spallek J, Richter M. Explaining socioeconomic inequalities in self-rated health: a systematic review of the relative contribution of material, psychosocial and behavioural factors. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(6):565–575.

- Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health; Stockholm: Institutet för Framtidsstudier; 1991.

- Parisi SM, Bodnar LM, Dubowitz T. Weight resilience and fruit and vegetable intake among African-American women in an obesogenic environment. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(2):391–402.

- Sachdev PK, Freeland-Graves J, Ranjit N, et al. Role of dental nutrition knowledge and socioecological factors in dental caries in low-income women. Health Educ Behav. 2021.

- Gularte J. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors about physical activity, weight, nutrition and health in young, low-income Latina adults. San Francisco: University of California; 2011.

- Krause N. Negative interaction and heart disease in late life: exploring variations by socioeconomic status. J Aging Health. 2005;17(1):28–55.

- Finlayson TL, Siefert K, Ismail AI, et al. Psychosocial factors and early childhood caries among low-income African-American children in Detroit. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(6):439–448.

- Brogan K, Idalski Carcone A, Jen K-LC, et al. Factors associated with weight resilience in obesogenic environments in female African-American adolescents. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):718–724.

- Burgette JM. Family resilience and connection is associated with dental caries in US children. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2022;7(1):61–70.

- Albino J, Tiwari T, Henderson WG, et al. Learning from caries-free children in a high-caries American Indian population. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(4):293–300.

- Boshoff K, Dollman J, Magarey A. An investigation into the protective factors for overweight among low socio-economic status children. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18(2):135–142.

- Bloom EL, Bogart A, Dubowitz T, et al. Longitudinal associations between changes in cigarette smoking and alcohol use, eating behavior, perceived stress, and self-rated health in a cohort of low-income Black adults. Ann Behav Med. 2022;56(1):112–124.

- Chen X, Wang Y. Is ideal body image related to obesity and lifestyle behaviours in African American adolescents? Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38(2):219–228.

- Kramer RF, Coutinho AJ, Vaeth E, et al. Healthier home food preparation methods and youth and caregiver psychosocial factors are associated with lower BMI in African American youth. J Nutr. 2012;142(5):948–954.

- Vedovato GM, Surkan PJ, Jones-Smith J, et al. Food insecurity, overweight and obesity among low-income African-American families in Baltimore City: associations with food-related perceptions. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(8):1405–1416.

- Walcott-McQuigg J. Psychological factors influencing cardiovascular risk reduction behavior in low and middle income African-American women. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2000;11(1):27–35.

- Han E, Jones-Smith J, Surkan PJ, et al. Low-income African-American adults share weight status, food-related psychosocial factors and behaviours with their children. Obes Sci Pract. 2015;1(2):78–87.

- Finlayson TL, Siefert K, Ismail AI, et al. Reliability and validity of brief measures of oral health-related knowledge, fatalism, and self-efficacy in mothers of African American children. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27(5):422–428.

- Litt MD, Reisine S, Tinanoff N. Multidimensional causal model of dental caries development in low-income preschool children. Public Health Rep. 1995;110(5):607–617.

- Speirs KE, Hayes JT, Musaad S, et al. Is family sense of coherence a protective factor against the obesogenic environment? Appetite. 2016;99:268–276.

- Sanders AE, Lim S, Sohn W. Resilience to urban poverty: theoretical and empirical considerations for population health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1101–1106.

- Booth JM, Jonassaint CR. The role of disadvantaged neighborhood environments in the association of John Henryism with hypertension and obesity. Psychosom Med. 2016;78(5):552–561.

- Brody GH, Yu T, Miller GE, et al. Resilience in adolescence, health, and psychosocial outcomes. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20161042.

- Evans GW, Fuller-Rowell TE, Doan SN. Childhood cumulative risk and obesity: the mediating role of self-regulatory ability. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e68–e73.

- Ling J, Xu D, Robbins LB, et al. Obesity and hair cortisol: relationships varied between low-income preschoolers and mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(12):1495–1504.

- Kallem S, Carroll-Scott A, Rosenthal L, et al. Shift-and-persist: a protective factor for elevated BMI among low-socioeconomic-status children. Obesity. 2013;21(9):1759–1763.

- Dammann KW, Smith C. Food-related environmental, behavioral, and personal factors associated with body mass index among urban, low-income African-American, American Indian, and Caucasian women. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25(6):e1–e10.

- Lim S, Zoellner JM, Ajrouch KJ, et al. Overweight in childhood: the role of resilient parenting in African-American households. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(3):329–333.

- Nicolau B, Marcenes W, Bartley M, et al. A life course approach to assessing causes of dental caries experience: the relationship between biological, behavioural, socio-economic and psychological conditions and caries in adolescents. Caries Res. 2003;37(5):319–326.

- Abreu LG, Elyasi M, Badri P, et al. Factors associated with the development of dental caries in children and adolescents in studies employing the life course approach: a systematic review. Eur J Oral Sci. 2015;123(5):305–311.

- WHO (World Health Organization). Strengthening resilience: a priority shared by health 2020 and the sustainable development goals. Copenhagen; 2017.

- Silva A d, Alvares de lima ST, Vettore MV. Protective psychosocial factors and dental caries in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2018;28(5):443–458.

- Bernabé E, Watt RG, Sheiham A, et al. Sense of coherence and oral health in dentate adults: findings from the Finnish Health 2000 survey. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(11):981–987.

- Pitchon A, Gomes VE, Ferreira EFE. Salutogenesis in oral health research in preschool children: a scoping review. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2021;31(3):372–382.

- Baker SR, Mat A, Robinson PG. What psychosocial factors influence adolescents’ oral health? J Dent Res. 2010;89(11):1230–1235.

- Elyasi M, Abreu LG, Badri P, et al. Impact of sense of coherence on oral health behaviors: a systematic review. PLOS One. 2015;10(8):e0133918.

- Silva AN, Mendonça MH, Vettore MV. A salutogenic approach to oral health promotion. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24 Suppl 4:s521-30.

- Lindstrom B, Eriksson M. Salutogenesis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(6):440–442.

- Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(5):376–381.

- Rivera F, García-Moya I, Moreno C, et al. Developmental contexts and sense of coherence in adolescence: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2013;18(6):800–812.

- Hall-Scullin E, Goldthorpe J, Milsom K, et al. A qualitative study of the views of adolescents on their caries risk and prevention behaviours. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(1):141.

- Lindmark U, Abrahamsson K. Oral health-related resources – a salutogenic perspective on Swedish 19-year-olds. Int J Dent Hyg. 2015;13(1):56–64.

- Marley C, Mauki B. Resilience and protective factors among refugee children post-migration to high-income countries: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29(4):706–713.

- Ostberg A-L, Jarkman K, Lindblad U, et al. Adolescents’ perceptions of oral health and influencing factors: a qualitative study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2002;60(3):167–173.

- Rai NK, Tiwari T. Parental factors influencing the development of early childhood caries in developing nations: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2018;6:1–8.