Abstract

Background: Distinguishing branchial cleft cysts (BCCs) from cystic metastases of a human papillomavirus (HPV) positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) is challenging. Fine needle aspirates (FNAs) from cystic metastasis may be non-representative, while reactive squamous cells from BCC can be atypic. Based on cytology and with the support of HPV DNA positivity many centers treat cystic metastasis oncological and thus patients are spared neck dissection. To do so safely, one must investigate whether HPV DNA and p16INK4a overexpression is found exclusively in cystic metastases and not in BCC.

Patients and methods: DNA was extracted from formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) surgically resected BCCs from 112 patients diagnosed 2007–2015 at Karolinska University Hospital and amplified by PCR. A multiplex bead-based assay used to detect 27 HPV-types and p16INK4a expression was analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Results: All 112 BCCs were HPV DNA negative, and of 105 BCCs possible to evaluate for p16INK4a, none overexpressed p16INK4a.

Conclusions: HPV DNA and p16INK4a overexpression were absent in BCCs. Lack of HPV DNA and p16 protein overexpression in BCCs is helpful to discriminate benign BCCs from HPV+ OPSCC metastasis. HPV testing definitely has a role in the diagnostics of cystic masses of the neck.

Chinese abstract

背景:将鳃裂囊肿(BCC)与人乳头状瘤病毒(HPV)阳性口咽鳞状细胞癌(OPSCC)的囊性转移区别开, 是有难度的。自囊性转移的细针抽吸物(FNA)可能是非代表性的, 而BCC的反应性鳞状细胞可能是非典型的。根据细胞学, 并且有HPV DNA阳性的支持, 许多中心能治疗囊性转移的肿瘤, 因此患者可免受颈部手术。为安全起见, 必须弄清楚HPV DNA和p16INK4a过度是否仅发现于囊性转移灶, 而不是BCC中。

患者和方法:从福尔马林固定石蜡包埋(FFPE)的经外科手术切除的BCC中提取DNA, 并通过PCR将其放大。BCC来自于2007至2015年在卡罗林斯卡大学医院诊断的112名患者。通过免疫组织化学(IHC)来分析用于检测27种HPV型和p16INK4a表达的多重珠基测定法。

结果:所有112例BCC为HPV DNA阴性, 其中105例BCC可能评估出p16 INK4a, 没有过度表达p16 INK4a。

结论:BCC中HPV DNA和p16 INK4a过表达缺失。在BCC中缺乏HPV DNA和p16蛋白过表达有助于区分良性BCC和HPV + OPSCC转移。 HPV检测在颈部囊性肿块的诊断中肯定起着作用。

Introduction

Branchial cleft cysts (BCCs) are embryological remnants due to incomplete obliteration of a branchial cleft during embryogenesis [Citation1]. BCC type II, derived from the second branchial cleft, accounts for 90% of all BCC cases and clinically presents as a lateral neck mass typically situated anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the mid part of the neck [Citation2].

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) often presents as a neck mass – a lymph node metastasis and in most cases the metastasis is typically solid [Citation3]. Notably however, in human papillomavirus positive (HPV+) oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), the metastasis in the neck is often cystic [Citation3]. It is, therefore, clinically challenging to differentiate between a cystic metastasis originating from a primary HNSCC malignancy, i.e. an HPV+ OPSCC, mimicking a BCC and a benign BCC, especially in patients over 40 years of age [Citation2–8]. The incidence of unsuspected squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in routinely excised BCCs in adults has been reported to be 3–24% and even more frequent in elderly patients [Citation2–8].

Patients over 40 years of age with BCCs are, therefore, often subjected to a fairly extensive diagnostic workup to exclude a malignancy. At Karolinska University Hospital, these patients do computed tomography (CT) followed by panendoscopy with biopsies of the base of tongue and nasopharynx and tonsillectomy in order to minimize the risk of missing a possible primary tumor before surgery of the BCC [Citation9].

It has previously been shown that neck metastasis of HPV+ OPSCCs are HPV DNA positive and that the detection of HPV DNA in the fine needle aspirate cytology (FNAC) is correlated to the presence of an HPV+ OPSCC [Citation10–12]. HPV DNA is also frequently detected in many cases of cancer of unknown primary (CUP) in the head and neck region, and in these cases, they usually originate from an HPV+ OPSCC [Citation13].

It has, however, not been sufficiently investigated whether HPV DNA can be present in benign lateral neck cysts, including BCCs, and only minor studies by others and we have shown that all 20 and 16 BCCs, respectively, were HPV DNA negative [Citation11,Citation12]. Moreover, the presence of p16INK4a (p16) overexpression, a widely used surrogate marker for HPV-positive head and neck cancer, has not been extensively evaluated as a diagnostic tool, although it has in some small studies reported to be expressed in >40% of the BCC cases [Citation14].

These data increase the complexity when trying to separate benign BCCs from malignant metastatic HPV+ OPSCCs. For this purpose, we examined whether HPV DNA and p16 INK4a overexpression could be observed in a large BCC cohort in Stockholm, Sweden.

Material and methods

Patients. In total, 138 patients with BCC diagnosed 2007–2015 at the Karolinska University Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden) were identified through the hospital database and of these 112 were included in the study. Of the 26 excluded patients, 22 patients did not have surgery and, therefore, lacked material for analysis, and four patients did not have representative cystic material upon evaluation by immunohistochemistry (IHC). The size of the cysts variated around 2–8 cm. Patient characteristics are collected from patient records, see .

Table 1. Patient’s characteristics and absence of HPV DNA in branchial cleft cysts biopsies.

Detection of human papillomavirus. DNA was extracted from 15 μm formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) BCC tissue sections using the Roche High Pure FFPET DNA Isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions [Citation15]. For each tumor sample, a blank paraffin section was included as a negative control to detect possible cross-contamination between samples. Presence of HPV DNA was analyzed in the extracted DNA (10 ng/sample) using a multiplex bead-based assay for 27 HPV types (HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 26, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 73 and 82) with β-globin included as a positive control for amplifiable DNA as described before [Citation15].

P16INK4a (p16) expression. Only, 105 of the 112 samples examined for the presence of HPV DNA had sufficient material for p16 analysis, which was performed by IHC using the mouse monoclonal antibody CINtec® p16 Histology ((Ventana CINtec® p16 Histology, clone E6H4, Roche AB, Stockholm, Sweden). An OPSCC with known p16 overexpression was used as a positive control and staining was performed as described before, except for the p16 antibody used [Citation15]. All sections were assessed by two scientists. A strong diffuse cytoplasmatic/nuclear staining in ≥70% of the epithelial cells of BCC was considered as positive for p16 overexpression, and <70% as negative as previously described [Citation13,Citation16].

Results

In total, 112 BCC FFPE samples were analyzed to determine the presence of HPV DNA. HPV DNA was not detected in any of the samples ().

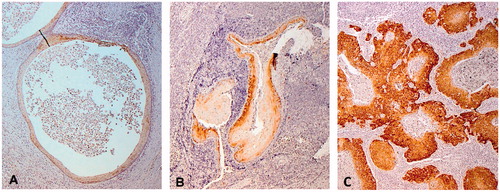

Furthermore, 105 of the above samples could be evaluated for p16 expression and none of the samples overexpressed p16 as reported in . The BCCs generally showed a weak degree of p16 expression, with the majority of the samples having 0–20% staining (). Staining was typically limited to the epithelium lining the inside of the cyst or a focal staining, as presented, e.g. in , and did not correspond to the p16 overexpression observed, e.g. a HPV+ OPSCC as demonstrated in .

Figure 1. Focal p16 staining of BCC (A and B) as compared to HPV + OPSCC (C), where a diffuse strong cytoplasmatic/nuclear staining in >70% of the cells was observed (positive control).

Table 2. Percentage of branchial cleft cyst epithelium showing p16 expression analyzed by immunohistochemistry.

Discussion

In this study, all 112 included BCC FFPE samples were found to be HPV DNA negative, and of the 105/112 samples possible to assess for p16 INK4a staining none overexpressed p16 according to the criteria for overexpression as a surrogate marker for HPV in OPSCC [Citation13,Citation16].

The fact that HPV DNA was not detected in any of the BCC FFPE samples strengthens the hypothesis that it can be possible to distinguish a cystic metastasis from an HPV+ OPSCC from a BCC using HPV DNA analysis. This is also supported by our previous prospective study, where when HPV DNA was detected in FNAC from neck masses of unknown origins, the tumor emanated from an OPSCC in 100% of the cases [Citation12]. Likewise, when HPV DNA was disclosed in DNA extracted from fine needle aspirate (FNA) smears it was derived from HPV+ OPSCCs, and never detected in DNA from benign conditions, including BCCs [Citation11].

To further investigate a way to distinguish benign BCCs from metastatic cysts, the evaluation of p16, involved in the pRb and p53 pathways, was also assessed in this study. It is known that during an HPV infection, the E7 protein binds and inactivates pRb, while the E6 protein degrades p53, leading to a feedback up-regulation of p16 and, therefore, high expression (>70%) of the p16 protein is often used as surrogate biomarker for HPV induced head and neck cancer [Citation16]. To our knowledge, no study has shown >70% overexpression of p16 INK4a in BCCs [Citation14]. In this study, no samples overexpressed p16, and weak p16 staining (0–20% in the epithelial of the cysts) was present in the majority of the samples (92/105). A minority of the samples exhibited a slightly stronger staining (21–20%), but this was way below that required to define the sample as HPV-positive according to present criteria [Citation13,Citation16].

Again, it is challenging to radiological and cytological, separate a well-differentiated SCC from a benign condition such as BCC in the neck [Citation17,Citation18]. FNAC has a diagnostic accuracy of about 90% and more for solid cervical masses, while the technique is less reliable in cystic nodules and the distinction of a BCC from a cystic SCC metastasis is difficult [Citation19]. BCC that have been infected may display ‘reactive’ squamous cells that may be interpreted as malignant [Citation5]. On the other hand, the cytological yield from cystic metastases may be very sparse and if no primary tumor is found, a solitary malignant cystic metastasis in the lateral neck may be misdiagnosed as BCC. The incidence of unsuspected SCC in cervical cysts initially diagnosed as BCCs has been reported to be 3.6–24% [Citation2–8]. DNA analysis of FNAC has previously been suggested as a useful tool to separate a BCC from a HNSCC metastasis, while others suggest intraoperative frozen section analysis is better [Citation5,Citation20].

Before the HPV era patients with cytologically diagnosed metastasis in the neck without an identified primary tumor, i.e. CUP were routinely treated with neck dissection in order to histopathologically verify a cancer diagnosis, since cytology was not considered altogether reliable. Today, many centers provide oncological treatment of cystic metastases on the basis of cytology results only, with the support of HPV positivity, hence patients are spared neck dissection. However, if HPV DNA would be found in a proportion of BCCs, there would be a risk of giving oncological treatment to a BCC with ‘reactive’ cytology. Notably, this study shows that when testing a large cohort of BCCs none harbored HPV.

Whether lack of HPV and a clear benign cytology is sufficient for a BCC diagnosis, and an extensive diagnostic work up for patients >40 years of age can be avoided, i.e. DT-/MRI-scan, panendoscopy with biopsies of the epipharynx and base of tongue and tonsillectomy, before BCC removal remains to be investigated. One possibility would be to add the analysis of DNA ploidy to the FNAC analysis of a suspected BCC, where being diploid would in this case further strengthen the BCC diagnosis [Citation5].

Nevertheless, others and we have previously shown that HPV DNA detection in FNAC is feasible [Citation11,Citation12]. As FNAC is already part of the diagnostic work up of BCC, we suggest that the HPV-status of the FNAC should be investigated for BCC. If the cytology from a cystic metastasis shows 100% benign cells and the FNAC is also HPV-negative this strengthens the evidence that it is indeed a BCC. In the future, this may influence further diagnostic procedures and treatment. This study highlights the usefulness of HPV DNA-testing (in order not to miss a possible HPV+ OPSCC) also in cystic lesions with benign cytological morphology, something that is infrequently performed today.

One limitation of the study is that the HPV-DNA analysis was performed on histological sections and not in parallel on FNAC-material. However, concordance between the use of histology and FNAC for the analysis of HPV DNA has previously been shown [Citation11,Citation12].

In summary, the presence of HPV DNA and p16 protein overexpression was analyzed in a large cohort of BCC and no presence of HPV DNA by PCR or cells exhibiting p16 overexpression defined as >70% of the epithelial cells being p16 positive was found. We, therefore, conclude that lack of HPV DNA and p16 protein overexpression in BCCs is helpful to discriminate benign BCCs from HPV+ OPSCC metastasis. To conclude, the analysis of HPV DNA has a definite role in the diagnostics of masses in the neck region and should be implemented in clinical practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bajaj Y, Ifeacho S, Tweedie D, et al. Branchial anomalies in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:1020–1023.

- Muller S, Aiken A, Magliocca K, et al. Second branchial cleft cyst. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:379–383.

- Katabi N, Lewis JS. Update from the 4th edition of the world health organization classification of head and neck tumours: what is new in the 2017 WHO blue book for tumors and tumor-like lesions of the neck and lymph nodes. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:48–54.

- Pietarinen-Runtti P, Apajalahti S, Robinson S, et al. Cystic neck lesions: clinical, radiological and differential diagnostic considerations. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:300–304.

- Nordemar S, Tani E, Högmo A, et al. Image cytometry DNA-analysis of fine needle aspiration cytology to aid cytomorphology in the distinction of branchial cleft cyst from cystic metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1997–2000.

- Granström G, Edström S. The relationship between cervical cysts and tonsillar carcinoma in adults. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:16–20.

- Gourin CG, Johnson JT. Incidence of unsuspected metastases in lateral cervical cysts. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1637–1641.

- Sheahan P, O’Leary G, Lee G, et al. Cystic cervical metastases: incidence and diagnosis using fine needle aspiration biopsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:294–298.

- Karolinska Universitetssjukhuset. Vårdprogram. Halscysta. Vårdprogram Halscysta. Lateral. Stockholm: Karolinska Universitetssjukhuset; 2016.

- Begum S, Gillison ML, Ansari-Lari MA, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus in cervical lymph nodes: a highly effective strategy for localizing site of tumor origin. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6469–6475.

- Channir HI, Grønhøj Larsen C, Ahlborn LB, et al. Validation study of HPV DNA detection from stained FNA smears by polymerase chain reaction: improving the diagnostic workup of patients with a tumor on the neck. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:820–827.

- Sivars L, Landin D, Haeggblom L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA detection in fine-needle aspirates as indicator of human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcina: a prospective study. Head Neck. 2017;39:419–426.

- Sivars L, Näsman A, Tertipis N, et al. Human papillomavirus and p53 expression in cancer of unknown primary in the head and neck region in relation to clinical outcome. Cancer Med. 2014;3:376–384.

- Cao D, Begum S, Ali SZ, et al. Expression of p16 in benign and malignant cystic squamous lesions of the neck. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:535–539.

- Nordfors C, Vlastos A, Du J, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence is high in oral samples of patients with tonsillar and base of tongue cancer. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:491–497.

- Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35.

- Krane JF. Role of cytology in the diagnosis and management of HPV-associated head and neck carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:117–126.

- Yasui T, Morii E, Yamamoto Y, et al. Human papillomavirus and cystic node metastasis in oropharyngeal cancer and cancer of unknown primary origin. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95364.

- Layfield LJ. Fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of head and neck lesions: a review and discussion of problems in differential diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:798–805.

- Begbie F, Visvanathan V, Clark LJ. Fine needle aspiration cytology versus frozen section in branchial cleft cysts. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129:174–178.