Abstract

Background

Smell and taste dysfunctions (STD) are frequently observed in patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

Objectives

To investigate the clinical characteristics of STD in COVID-19 patients.

Material and Methods

One-hundred six COVID-19 adult patients with the Omicron variant were enrolled. The clinical features of patients with and without STD were compared using questionnaires, laboratory tests, and imaging examinations.

Results

Of the 76 patients with smell and/or taste dysfunction, age (p = .002), vaccination time (p = .024), history of systemic diseases (p = .032), and smoking status (p = .044) were significantly different from those of the controls (n = 34). Fatigue (p = .001), headache (p = .004), myalgia (p = .047), and gastrointestinal discomfort (p = .001) were observed more frequently in these patients than in controls. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score of these patients was significantly higher than that of controls (p < .001). The taste visual assessment scale score of the STD group was significantly lower than that of the taste dysfunction group (p = .001), and perceptions of sour, sweet, and salty tastes were worse in the STD group than in the taste dysfunction group (p < .001).

Conclusions and Significance

COVID-19 patients had similar changes in smell and/or taste dysfunctions and worse emotional states, possibly correlated with some factors, including age and vaccination time.

Chinese Abstract

背景:在冠状病毒(COVID-19)患者中经常观察到嗅觉和味觉功能障碍(STD)。

目的:调查 COVID-19 患者 STD 的临床特征。

材料和方法:共106 名患有 Omicron 变体的 COVID-19 成年患者注册。 使用问卷、实验室检查和影像学检查比较有和没有 STD 患者的临床特征。

结果:在 76 名有嗅觉和/或味觉功能障碍的患者中, 年龄 (p=.002)、疫苗接种时间 (p=.024)、全身性疾病史 (p=.032) 和吸烟状况 (p=.044) 与对照组(n = 34)差异很大。 在这些患者中观察到的疲劳 (p=.001)、头痛 (p=.004)、肌痛 (p=.047) 和胃肠道不适(p=.001)比对照组更频繁。这些患者的医院焦虑抑郁量表评分显著高于对照组(p<.001)。 STD组味觉视觉评估量表评分明显低于味觉障碍组 (p=.001);STD 组酸、甜、咸味觉感应比味觉障碍组 (p<.001)还要糟。

结论和意义:COVID-19 患者在嗅觉和/或味觉功能障碍方面有相似的变化, 而他们的情绪状态更糟。这可能与一些因素有关, 包括年龄和疫苗接种时间。

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which was first reported in China in 2019, has reached the pandemic level and has caused global concern [Citation1]. Like all RNA viruses, SARS-CoV-2 is prone to mutation and the emergence of new variants. Since the start of the pandemic, several variants of concern have been identified, with the Omicron variant (BA.1) becoming the most prevalent worldwide in December 2022. Although an omicron variant infection is considered to have lower severity and mortality rate, it has higher transmissibility and causes many accompanying symptoms [Citation2].

Fever, cough, fatigue, sore throat, and dyspnea are considered key symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Recently, studies have shown that smell and taste dysfunctions (STD) are also present in a high percentage of patients with COVID-19 [Citation3–4]. It has been reported that smell and taste alterations could also affect the patient’s mood, reduce the quality of life, and even potentially have a negative impact on health status [Citation5].

In recent years, a series of studies have explored the functional alterations of smell and taste in patients with COVID-19. Based on different virus strains, races, and severity of COVID-19, the prevalence of smell dysfunction (SD) ranged from 5.14% to 98.33%, and the prevalence of taste dysfunction (TD) ranged from 5.61% to 92.65% [Citation6]. Compared to previous variants, the proportion of patients infected with Omicron variant experiencing STD is significantly lower [Citation7]. Although the smell and taste of most people could be recovered following SARS-CoV-2 infection, there were still a small number of people who could not improve their sense of smell and taste for months and there is a negative correlation between the improvement of olfactory function and the duration of infection [Citation8]. However, patients with COVID-19 with complete vaccination did not show a lower incidence of STD [Citation9].

With the rapid spread of the Omicron variant in Zhejiang, China, STD is becoming an increasingly public concern. Our study aimed to explore the characteristics of changes in smell and taste during SARS-CoV-2 infection and investigate the risk factors related to STD as well as the laboratory indicators that can predict these symptoms. In addition, we attempted to clarify the relationship between STDs and other symptoms in patients with COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Study design

A retrospective, single-center cohort study was conducted. The participants consisted of infected physicians and nurses at our hospital and patients screened by otolaryngologists in the outpatient department. Our study was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the medical ethics committee of our hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The data were analyzed anonymously.

Participants

Patients with non-severe laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant infections were enrolled between September and November 2022. We used reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm SARS-CoV-2 infection and the viral genomes showed that the participants were infected with a sub-lineage of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Patients under 18 years of age, with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection [Citation9], with smell and taste dysfunctions before COVID-19, with a history of mental illness that was unable to complete questionnaires and laboratory examinations, and those who refused to cooperate were excluded. Based on whether the patients had SD or TD, we divided them into the control (patients without smell or taste dysfunction), SD (patients with only smell dysfunction), TD (patients with only taste dysfunction), and STD (patients with both smell and taste dysfunction) groups.

Outcomes

A questionnaire was designed to obtain relevant information about the participants. We used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) to evaluate anxiety and depression in the participants. When answering the questionnaire, participants would have a professional otolaryngologist explain the questions that they could not understand.

In previous interviews and questionnaires, we collected the following information: basic characteristics such as sex, age, history of systemic diseases (such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases), history of nasal and oral diseases, history of trauma, vaccination times, history of smoking and alcohol drinking, and diet preference; associated symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as fever, fatigue, nasal congestion and runny nose, sore throat, cough, headache, muscle or joint pain; drugs administration during the SARS-CoV-2 infection; status of anxiety and depression (by HADS); and changes of smell and taste, such as the visual assessment scale (VAS) of smell and taste and the Taste Strips (Burghart Messtechnik, Germany) to evaluate different types of flavors affected after SARS-CoV-2 infection. The alteration types of smell or taste (such as parosmia, phantosmia, phantogeusia, and parageusia) were also noted.

We also collected blood samples from the participants and recorded the white blood cell (WBC) count, percentage of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, hemoglobin, platelet count, C-reactive protein (CRP), prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrinogen, D-dimer, and procalcitonin (PCT).

Chest tomography, laryngoscopy, and nasal endoscopy were also used to evaluate the clinical features of the patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables are presented as numbers (%), and continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). The confidence interval (CI) was set at 95%, and the level of significance was set at .05. The independent t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the differences in continuous variables, Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the differences in ranked variables and the chi-square test was used to compare the differences in categorical variables between the SD, TD, STD, and control groups. Additionally, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis to identify the risk factors for the occurrence of STD.

Results

Cohort characteristics and laboratory findings of the STD and control groups

We included 153 COVID-19 participants in this study. The data of 106 patients were finally analyzed after excluding the patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 31) and those who were lost to follow-up (n = 16). They consisted of 49 patients with both smell and taste dysfunction (STD group), eight patients with smell dysfunction only (SD group), 15 patients with taste dysfunction only (TD group), and 34 patients with neither smell nor taste dysfunction (control group). Next, we compared the baseline characteristics of the STD, SD, and TD groups and the control group. The results are summarized in . Of the 72 participants in the STD + SD + TD group, 51.4% were male (n = 37) and 48.6% were female (n = 35). In the control group, 44.1% were male (n = 15) and 55.9% were female (n = 19). Notably, of all the basic characteristic information collected, age (p = .002), vaccination times (p = .024), history of systemic diseases (p = .032), and smoking status (p = .044) of STD + SD + TD groups were significantly different from those of the controls. Among all COVID-19-associated symptoms, fatigue (p = .001), headache (p = .004), myalgia (p = .047), and gastrointestinal discomfort (p = .001) were more frequently observed in patients with STD + SD + TD. We also found that the HADS score of the STD + SD + TD group was significantly higher than that of the control group (p < .001). However, in Spearman's analysis of the correlation between HADS score and smell/taste score, there was no significant correlation between HADS score and smell score, as well as between the HADS score and taste score (p > .05).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the STD in COVID-19 patients with the Omicron variant.

We also analyzed the serological results of STD + SD + TD and control patients, which are summarized in . We found no statistical difference in terms of WBC count, percentage of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, hemoglobin, platelet count, C-reactive protein, PT, APTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer, PCT (p > .05).

Table 2. Comparison of laboratory findings between the STD + SD + TD and control groups.

In the binary logistic regression analysis of STD, we found that age (OR: .948, 95% CI: .9–.998), history of systemic disease (OR: .185, 95% CI: .043–.794), fatigue (OR: 4.215, 95% CI: 1.177–15.096) and HADS score (OR: 1.269, 95% CI: 1.139–1.413) seem to be the risk factors of STD (p < .05). The results are presented in .

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of risk factors for STD.

Analysis of smell and taste in the STD, SD, and TD groups

We compared smell and taste differences among the STD, SD, and TD groups, and the results are presented in . Although the smell VAS scores of the STD and SD groups were not significantly different (p = .727), the taste VAS score of the STD group was significantly lower than that of the TD group (p = .001). Our study also found that the number of taste types affected due to Omicron variant infection in the STD group was greater than that in the TD group (p < .001), indicating more severe taste impairment in the STD group.

Table 4. Comparison of smell and taste in the SD, TD, and STD groups.

In the STD and SD groups, 7/49 and 0/8 patients (14.3% and 0%, respectively) reported parosmia (olfactory inversion) while 4/49 and 1/8 patients (8.2% and 12.5%, respectively) reported phantosmia (olfactory hallucination), with no significant differences in both groups (p > .05). In the STD and TD groups, 33/49 and 13/15 patients (59.2% and 53.3%, respectively) reported parosmia (taste inversion) while 29/49 and 8/15 patients (67.3% and 86.7%, respectively) reported phantogeusia (taste hallucination), with no significant differences in both groups (p > .05). In addition, the duration of SD and HADS scores in the STD and SD groups and the duration of TD and HADS scores in the STD and TD groups also showed no statistical differences (p > .05).

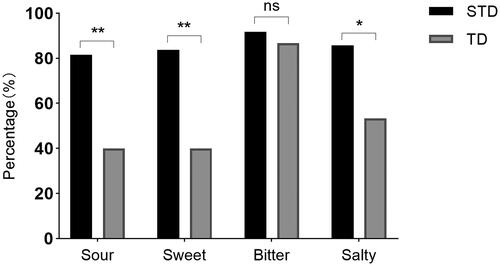

In our further study on the impairment of different taste perceptions in the STD and TD groups, we found that among sour, sweet, salty, and bitter, the proportion of participants who had an impairment of bitter perception was highest in both the STD and TD groups (91.80% and 86.70%, respectively). The proportion of participants with impaired perception of sour, sweet, and salty tastes in the STD group was significantly higher than that in the TD group (p = .003, p = .002, and p = .012, respectively). The results are shown in .

Figure 1. Comparison of different types of tastes affected due to the Omicron variant infection between smell and taste dysfunction (STD) and taste dysfunction (TD) groups. Among sour, sweet, salty, and bitter, the proportion of participants with impaired bitter perception was the highest in both STD and TD groups (91.80% and 86.70%, respectively). The proportion of participants with impaired perception of sour, sweet, and salty taste in the STD group was significantly higher than that in the TD group (p = .003, p = .002, and p = .012, respectively).

Discussion

STD is an important symptom of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The exact mechanism of STD after SARS-CoV-2 infection is not fully understood. Some researchers believe that SD might be the result of localized airflow obstruction or sensorineural damage [Citation10]. A recent study conducted by Eliezer et al. reported olfactory cleft obstruction in patients with COVID-19 with SD through magnetic resonance imaging [Citation11], and Lee et al. found that microvascular injury in the olfactory bulb could be another explanation for SD in patients with COVID-19 [Citation12]. TD may be due to the local inflammatory reaction caused by SARS-CoV-2 invading the epithelial cells of the tongue through the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptor [Citation13].

In this study, we found that younger people, fewer vaccination times, no systemic diseases, and non-smokers were more likely to have smell or taste dysfunction when infected with the Omicron variant. A study conducted by Shen et al. reported that an increase in age was negatively related to the incidence of STD; however, they found no statistical differences in vaccination and smoking status between the SD and control groups [Citation14]. In addition, we found that with the increase in vaccination times, the proportion of patients with STD showed a downward trend, indicating that the vaccine may protect patients with COVID-19 from having STD. Although we found that a history of systemic diseases and smoking were negatively correlated with the occurrence of STD, we could not explain the cause of these results. Future research should focus on these findings and conduct more detailed studies.

It has been reported that fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, headache, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, and sore throat are the most common symptoms in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Asia [Citation15]. Although STD has a low incidence rate, it is difficult for patients and can last for a long time after other symptoms are relieved, sometimes even longer than 6 months. Our study found that smell and/or taste dysfunction occurred more often, together with fatigue, headache, myalgia, and gastrointestinal discomfort. Although the specific mechanism of COVID-19 damage to the peripheral nervous system is not clear, studies on STD may provide some ideas for further study in this direction. Another study showed that myalgia could be an independent risk factor for persistent olfactory loss, which may be because myalgia was the result of a high viral load, which may also be related to persistent SD [Citation16].

HADS is a scale that not only reflects the severity of anxiety and depression in patients, but also in the general population. It has a good balance between sensitivity and specificity in reflecting the two symptoms of anxiety and depression [Citation17]. Based on the results of the HADS, we found that anxiety and depression could also be complications of STD, although we did not obtain positive results in the correlation analysis between HADS score and smell/taste score. Loss or alteration of smell and taste can change the relationship between patients and their daily diet, which may further lead to changes in the appetite and eating framework of patients with COVID-19 [Citation5]. Finally, patients with STD with the Omicron variant may show emotions such as anxiety, depression, confusion, and loss of hope, and have a negative impact on their quality of life. Therefore, emotional changes should be considered as a sequela of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and some necessary and effective measures should also be taken.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on the differences in STD among patients with SD, TD, and STD in China. In our study, we found that the taste impairment of patients with STD was more severe than that of patients with SD, and the proportion of impairment of bitter perception was higher than that of sour, sweet, and salty. Parma et al. [Citation18] reported that 11% of patients with COVID-19 declared a single taste impairment and 48% declared two or more taste impairments. Another study reported a significant reduction in salty taste in patients with COVID-19 compared to controls [Citation19]. However, no significant difference in the reduction of olfaction was observed between patients with STD and SD. However, we did not measure the specific odor separately; therefore, we could not rule out that there were differences in the perception of some odors. Parosmia, phantosmia, phantogeusia, and parageusia were considered common sequelae of STD when infected with SARS-CoV-2, which could not simply be explained by the inflammatory reaction caused by the virus. Moreover, a study showed that they could also exist in patients with a normal sense of smell and taste [Citation19,Citation20]. We also found no differences in the proportions of parosmia, phantosmia, phantogeusia, and parageusia in the STD, SD, and TD groups.

Our study had some limitations and we are supposed to minimize the bias of the results. First, our sample size was relatively small; thus, the results are not representative and cannot be generalized. Therefore, our findings need to be further confirmed by studies with larger sample sizes. Second, we had limited laboratory tests available for our patients which may disregard some valuable biomarkers. Future studies can evaluate patients with STDs using more laboratory indicators to identify essential biomarkers. Third, the participants in our study were only limited to adult patients with non-severe COVID-19; hence, these conclusions may not be applicable to severe or pediatric patients.

Conclusions

As a common symptom of COVID-19 patients with the Omicron variant, the mechanism of STD is still unclear, and definite changes in smell and taste are not fully understood. Some factors such as age and vaccination time may be related to the occurrence of STD. Otherwise, attention should be paid to changes in the mental state of COVID-19 patients with STD. In addition, the changes in smell and taste in patients with STD, TD, and SD were not exactly the same. Future research needs to further investigate the pathological mechanisms of STD and explore more effective treatments for STD.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5.

- Maslo C, Friedland R, Toubkin M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients in South Africa during the COVID-19 omicron wave compared with previous waves. JAMA. 2022;327(6):583–584. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24868.

- Bianco MR, Modica DM, Drago GD, et al. Alteration of smell and taste in asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 patients in sicily, Italy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100(2_suppl):182S–185S. doi: 10.1177/0145561320981447.

- Borsetto D, Hopkins C, Philips V, et al. Self-reported alteration of sense of smell or taste in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis on 3563 patients. Rhinology. 2020;58(5):430–436. doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.185.

- Burges Watson DL, Campbell M, Hopkins C, et al. Altered smell and taste: anosmia, parosmia and the impact of long Covid-19. PLOS One. 2021;16(9):e0256998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256998.

- Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, et al. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):3–11. doi: 10.1177/0194599820926473.

- Boscolo-Rizzo P, Tirelli G, Meloni P, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related smell and taste impairment with widespread diffusion of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) Omicron variant. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022;12(10):1273–1281. doi: 10.1002/alr.22995.

- Bianco MR, Ralli M, Minni A, et al. Evaluation of olfactory dysfunction persistence after COVID-19: a prospective study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(3):1042–1048.

- Vaira LA, De Vito A, Lechien JR, et al. New onset of smell and taste loss are common findings also in patients with symptomatic COVID-19 after complete vaccination. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(2):419–421. doi: 10.1002/lary.29964.

- Parasher A. COVID-19: current understanding of its pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatment. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1147):312–320. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138577.

- Eliezer M, Hamel AL, Houdart E, et al. Loss of smell in patients with COVID-19: MRI data reveal a transient edema of the olfactory clefts. Neurology. 2020;95(23):e3145–e3152. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010806.

- Lee MH, Perl DP, Nair G, et al. Microvascular injury in the brains of patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):481–483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2033369.

- Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):8. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x.

- Shen J, Wu L, Wang P, et al. Clinical characteristics and short-term recovery of hyposmia in hospitalized non-severe COVID-19 patients with omicron variant in Shanghai, China. Front Med. 2022;9:1038938. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1038938.

- Young BE, Ong SWX, Kalimuddin S, et al. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1488–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204.

- Shahrvini B, Prajapati DP, Said M, et al. Risk factors and characteristics associated with persistent smell loss in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021;11(8):1280–1282. doi: 10.1002/alr.22802.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3.

- Parma V, Ohla K, Veldhuizen MG, et al. More than smell-COVID-19 is associated with severe impairment of smell, taste, and chemesthesis. Chem Senses. 2020;45(7):609–622. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjaa041.

- Ercoli T, Masala C, Pinna I, et al. Qualitative smell/taste disorders as sequelae of acute COVID-19. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(12):4921–4926. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05611-6.

- Ciurleo R, De Salvo S, Bonanno L, et al. Parosmia and neurological disorders: a neglected association. Front Neurol. 2020;11:543275. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.543275.