Abstract

This paper publishes the sixty-nine surviving very personal letters that Reichsgraf von Rumford wrote to Viscountess Palmerston after they met in Milan in 1793. The letters draw attention to the private domestic spaces of science and the critical importance of the aristocracy in scientific developments, topics that have both received some discussion recently. They were, however, not written with the purpose of providing historical evidence, but as part of a decade-long friendship which the letters trace, revealing, among other things, Rumford’s other amours. They also describe in some detail his thoughts about his activities as a member of the governing elite in Bavaria, his scientific and engineering researches (especially the writing and publication of his Essays), as well as what he would have termed his philanthropic efforts in Bavaria, Northern Italy, Britain, and Ireland. All this is framed within the context of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars that in so many ways, directly and indirectly, affected Palmerston’s and Rumford’s lives and work.

Introduction

On 22 June 1793 at the Hotel Auberge Imperial in Milan, where they were both staying, Benjamin Thompson, Reichsgraf von Rumford (1753–1814) (), on leave from working for the Bavarian government, met Mary Temple, Viscountess Palmerston (1752–1805) ().Footnote1 Both in their early forties, they were touring Italy, the one claiming he was restoring his health, the other in the hope of overcoming her grief at the death of a child from a smallpox inoculation. Set against the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, for the following eleven years until her death, they corresponded with an astonishing frankness in a quite remarkable set of letters, that, among other things, encompassed much about life, love, politics, science, and philanthropy.

FIGURE 1 J. P. P. Rauschmayr after Johann Georg Dillis, Portrait of Reichsgraf von Rumford (1797). Wellcome Collection 9153i. Public Domain.

FIGURE 2 Mary Tate, drawing of Viscountess Palmerston (1801). From Connell, Portrait of a Whig Peer, facing p. 129. (This drawing was in the Broadlands collection in 1957 and has subsequently disappeared. Despite due diligence, its current location has not been identified; furthermore, the rights to Connell’s book were not transferred to Andre Deutsch’s successor companies).

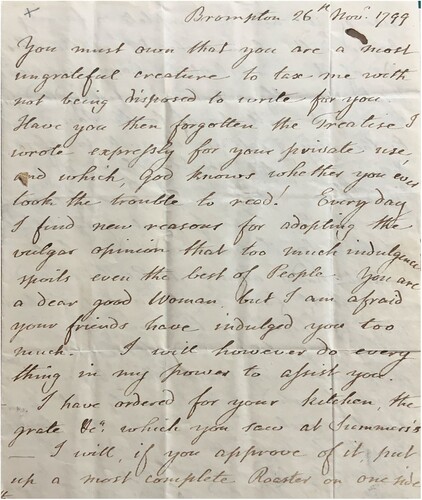

Of these letters, sixty-nine from Rumford to Palmerston have survived and are published here; unfortunately, none of the letters from her to him have been located.Footnote2 We do not know how many letters from Rumford have not survived; there are clearly gaps, especially between November 1799 and August 1801 and following the death of Palmerston’s husband in April 1802. Earlier, in 1794 and 1795, the content of letter 13 suggests a missing letter, while Palmerston, writing to her husband, referred to a letter from Rumford of 26 October 1794 that has not been foundFootnote3 – and there were probably others.

Rumford fell in love with Palmerston, but didn’t declare this until mid-1795 (letter 16), nearly two years after they had first met, a declaration he repeated a few months later (letter 21). It is quite clear that the affair was never consummated, much to Rumford’s regret (letter 28). That may explain why he went out of his way to tell her about his relationships with various mistresses.

From these very personal letters, it is apparent that for Rumford his scientific work, though important to him, was neither dominant nor insignificant, but simply a part of his overall life. The letters thus help locate scientific research and communication in the private domestic spaces of strong personal friendships and relationships, and, furthermore, they expand on recent studies demonstrating the key roles played by women and aristocrats (frequently the same individuals) in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British science and beyond.Footnote4 By ignoring, for whatever reasons, such connections, historians have missed their potential as explanatory categories in understanding the place of science in society and culture. For example, detailed below, these letters record some of the social interactions, including with the Palmerstons, that partially contributed unintentionally to the background of establishing the Royal Institution in 1799.Footnote5 A second example, also discussed below, of the critical importance of personal links, is that of the development of Rumford chimney fireplaces. Begun as an attempt to solve the problem of the smoking chimneys of the Palmerstons’ newly refurbished London townhouse, it was so successful that Rumford fireplaces were quickly installed in the houses of London high society and beyond, its continuing impact illustrated by an ambivalent reference in Northanger Abbey (1817).Footnote6 This success of his fireplaces led Rumford to reorganise his original plan for his Essays.

These and other instances of what we can learn from these letters are entirely contingent on their being written in the first place; they encompass so much more, especially personal matters, the reason for their existence. They contain the unedited spontaneous outpourings of Rumford’s views and feelings. They contrast strongly with the business-like nature of most of his other letters, for example to his publishers Cadell and Davies, which might be expected, but also to his friend Marc-Auguste Pictet which are almost exclusively on scientific and publishing matters.Footnote7 Rumford evidently trusted Palmerston completely and only once in these letters refrained from committing something confidential in a letter to her, presumably because he would see her shortly (letter 26). Over the decade of their correspondence, Rumford expressed his emotions and feelings to Palmerston including the desire for love (particularly hers), the state of his health (always a concern), and his paranoia (especially concerning the Bavarian court). Possibly his paranoia accounted for his need to tell Palmerston that he was not an atheist and did not have two faces, though the latter might have been a joke (letters 43 and 47). Altogether, these letters give an insight into the emotional life of a major figure, one of the more colourful men in the history of science.Footnote8

Rumford

Born on 26 March 1753 in the British colony of Massachusetts, at the age of nineteen Thompson married a wealthy and well-connected widow who held land in Rumford (now Concord), New Hampshire. Through her influence, he was appointed a major in the New Hampshire Militia. Thompson remained loyal to the King, but as the political and military situation deteriorated, even before the start of the formal rebellion of thirteen of the North American colonies, Thompson departed from North America leaving his wife (whom he would never see again) and daughter, Sarah Thompson, not yet two. In mid-1776 he moved to London where he worked for the Secretary of State for the Colonies, George Germain (1716–1785) MP for East Grinstead, though what he did in an official capacity is not clear. However, from the summer of 1778 at Germain’s summer residence, Stoneland Lodge in Sussex, Thompson began experiments on the power of gunpowder.Footnote9 Possibly on the basis of these experiments, the following year he was nominated to Fellowship of the Royal Society of London and elected in April. He was thus one of the earliest Fellows to be elected in the new Presidency of Joseph Banks that would last forty-two years. That Banks approved of the election is probably indicated by the signature of his close colleague and friend Daniel Solander (1733–1782) on Thompson’s certificate.Footnote10 Germain’s patronage of Thompson continued when towards the end of 1780 he was appointed Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. He held this position for a year,Footnote11 though in January 1781 Germain granted him leave to complete his elaborate, long (100 page), paper on his gunpowder experiments, read to the Royal Society of London on 29 March 1781 and subsequently published in its Philosophical Transactions.Footnote12 This process brought him into contact with another of Banks’s close associates, Charles Blagden, who would shortly (1784) become one of the Secretaries of the Royal Society of London. He kept a detailed diary during most of his life which shows that he and Thompson/Rumford retained close, if sometimes difficult, links during the ensuing decades.Footnote13

Later in 1781, now promoted to colonel and commanding the King’s American Dragoons, Thompson returned to North America where he held Long Island against the rebels with considerable ruthlessness including pursuing a scorched earth policy even after the peace treaty had been signed in 1783. He returned to London that year where he received an army half-pension and in September set out to tour the Continent intending to visit Strasbourg and Vienna.Footnote14 He sailed from Dover to Boulogne on the same ship as the historian Edward Gibbon (1737–1794) who described him somewhat sarcastically.Footnote15 According to an account provided by Thompson to Pictet more than a quarter of a century later,Footnote16 at Strasbourg he met Maximillian Joseph, later Duke of Deux Ponts or Zweibrücken, then a general in the French army. They spent much time recollecting and discussing the military actions of the American war and so impressed was the Duke with Thompson that he provided him with a letter of recommendation to his uncle Karl Theodor who had been Elector of the Palatinate since 1742 and also of Bavaria for nearly six years. On becoming Bavarian Elector, he moved his court from Mannheim to Munich where he became unpopular for a number of reasons including his dislike of Bavaria and Munich (he tried to exchange Bavaria for the Austrian Netherlands, now Belgium), infringing the rights of the city’s bürgers and his foreign policy, which though officially neutral tended, before the Revolution, to be pro-French.Footnote17 Indeed, the main language of the court was French and Thompson/Rumford had a tendency to use the French forms of German place names. But above all the Elector restored an absolutist monarchy with which Thompson was entirely in sympathy seeing it as a machine through which social reforms could be delivered and individual liberty restricted,Footnote18 detesting as he did the French Revolution, Jacobinism, and democracy (letters 50, 49, 28, and 66).

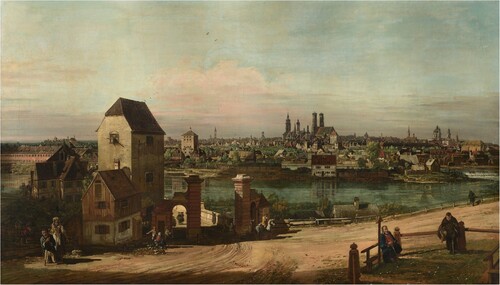

Intending to spend only a couple of days in Munich, Thompson was so well received that he stayed a fortnight,Footnote19 but by early December had continued east to Vienna. There he told Blagden of his plans to travel into Northern Italy (Trieste, Venice, Padua), before returning to Munich.Footnote20 In Munich, Thompson recommended his services to Karl Theodor who eagerly accepted the offer.Footnote21 However, as a British subject, Thompson required the permission of the King to begin his service and so returned briefly to London early in 1784. George III not only approved the Bavarian appointment but also knighted him on 23 February.Footnote22 Aside from an extended visit to Italy and one to Britain and Ireland, Thompson spent the next fourteen years mostly in Munich () initially as a colonel in the Bavarian army.Footnote23 He became part of the inner circle surrounding the Elector, helped by their sharing a mistress, Josepha, Gräfin Paumgarten (), who bore Thompson a daughter, Sophia (). Thompson undertook many and various tasks for the Elector, including planning and then in 1788, after overcoming significant opposition,Footnote24 implementing a drastic reorganisation of the Bavarian army for which role he was promoted to general.Footnote25 His work included producing new uniforms which a later visitor commented “dressed the Bavarian officers like paupers.”Footnote26 Closely linked with all these reforms, in Thompson’s mind at least,Footnote27 was the issue of the large number of beggars in Munich estimated to be 10% of the city’s population.Footnote28 By the end of 1789, Thompson had gained control of the workhouse system and on the first day of the new year organised, using the reformed army, the roundup of all of Munich’s beggars placing them in the military workhouse.Footnote29 His aim, as he put it later, was to “to make soldiers citizens, and citizens soldiers.”Footnote30

FIGURE 3 Bernardo Bellotto, View of Munich (c.1761), National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.64. Public domain.

FIGURE 4 Moritz Kellerhoven, portrait of Maria Josepha Barbara Johanna Nepomucena Gabriele von Lerchenfeld-Siessbach-Prennberg, Gräfin Paumgarten (c.1790). Courtesy of the Historical Society of New Hampshire, 1979.020.06.

FIGURE 5 Johann Georg Dillis (attributed), Walburger Sophia Barbara Paumgarten (c.1795). Courtesy of the Historical Society of New Hampshire, Edwin G. Burgum Collection, 1946.018.22 a.

Thompson’s influence on the policies of the Elector was both strong and covered a broad range of areas reflecting his seeming view of society as a physical machine by which the poor especially could be controlled. Two instances: workers in the military workhouse produced army uniforms designed by Thompson to secure the best insulating properties; second, seeking to minimise the cost of feeding the poor but maximising their nutrition, Thompson developed new fuel-efficient cooking ranges and a recipe for a nourishing (in his view) soup. But many of his activities were devoted to satisfying the whims of the Elector. One of these was the creation of what became known as the Englisher Garten, a huge public space (370 hectares), that still runs from the centre of Munich north-east along the River Isar for about 4 km.Footnote31 There the Elector staged fetes, concerts, led a faux rural life, and so on. The project was launched with an elaborate ball on 5 July 1789, perhaps in retrospect not the best timing for an absolute monarch to commence such an expensive venture.Footnote32 Nevertheless, Thompson would be involved in its development and construction in the ensuing years, overseeing the building of a semi-circular raked theatre capable of holding 3000 people (letters 15 and 16) possibly inspired by the Roman theatre in Verona that he knew well.

The Elector was also keen on having fountains for his various palaces and in order to fulfil his wishes, Thompson may have toyed with the idea of establishing a factory to manufacture steam engines; he certainly placed an order with Birmingham company of Boulton and Watt for a steam engine, later cancelled much to their annoyance. But that did at least allow Thompson in mid-1791 to send two engineers to Birmingham and, though Matthew Boulton was very suspicions of them, they did obtain access (through bribery) to the engines and made detailed drawings. However, steam-driven fountains were not introduced in Bavaria until after Thompson had left Munich.Footnote33

Thompson’s activities attracted criticism and opposition from both inside and outside the court. However, the Elector provided strong support and continued to reward Thompson: he became a Privy Counsellor in March 1790, received a lifetime pension (of around £400 annuallyFootnote34) a few months later and in February 1792 was promoted Chief of the General Staff.Footnote35 On 1 March 1792, the Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold II (1747–1792), died. Karl Theodor who had been, with Thompson’s aid, manoeuvring to succeed him, was only able to serve as Vicar of the Empire until the election of Franz II on 5 July 1792. However, that temporary role provided the Elector with the authority to ennoble, on 9 May 1792, Thompson as Reichsgraf von Rumford of the Holy Roman Empire (in French Comte, English Count).Footnote36

In October 1792, a French Revolutionary army began occupying the Rhineland following the Battle of Valmy (20 September) where it had defeated the invading Prussian and Austrian armies. The policy of Bavarian neutrality appears to have paid off and, although the Elector lost the Palatinate, Bavaria remained untouched. However, the Bavarian court was divided about how to deal with the crisis and according to the British ambassador, Rumford on the basis of “real and sometimes from feigned sickness” did not appear at court from mid-November, although he frequently met the Elector.Footnote37 Using ill-health as his reason Rumford started planning to undertake an extended journey to Italy, that commenced in mid-March 1793 and which by June had brought him to Milan where he met Viscountess Palmerston.

Palmerston

Viscountess Palmerston was born Mary Mee, the daughter of a prosperous banker whose only brother, Benjamin Mee, also entered banking though somewhat less successfully. In 1783, aged twenty-nine, she married, as his second wife, the wealthy Henry Temple, 2nd Viscount Palmerston, thirteen years her senior.Footnote38 The Viscountcy was in the Irish peerage allowing him sit as an MP (Whig) in the House of Commons which he did for various seats from 1762 until his death. They had three houses in England: a town house (20 Hanover Square), a villa at East Sheen, south-west of London, and a country house, Broadlands (), on the edge of Romsey in Hampshire.

The Palmerstons had five children (two boys and three girls) born between 1784 and 1790, but their fourth child, a daughter, died from an adverse reaction to a smallpox inoculation in May 1791 a few months after her second birthday. In July the following year, the family set out for the Grand Tour, though Viscount Palmerston had already visited Italy twice before.Footnote39 They were accompanied by their friends Blagden (for at least some portions) who recorded the journey in his diaryFootnote40 and by Mary Carter who acted as Palmerston’s companion; presumably there was also a retinue of servants and nurses, but they are invisible. The party passed through France (seeing Paris in the throes of Revolution and narrowly missing the massacre of the Swiss Guards) into Italy as far as Naples. In Rome, Blagden received a note from Rumford inviting him to meet probably in Milan;Footnote41 in the end, they met at Pavia where Alessandro Volta (1745–1827) showed them his experiments on animal electricity.Footnote42 The two then went on to Milan where they met the Palmerstons heading north for the summer.

Right from the start Reichsgraf von Rumford and Viscountess Palmerston enjoyed each other’s company and he attached himself to her party. Writing a week later to her brother during a visit to Lake Como, Palmerston commented:

Comte Le Rumford is particularly agreeable and a wonderful pleasant addition to our Society, he draws well, takes sketches as we are on the Lake and has a thousand resources. His History is a very extraordinary one and not the least surprising part that as a Stranger, he should have governed the Electorate of Bavaria for five years reformed numberless Abuses in the state and put the Army on a most respectable footing founded manufactories and almost new modelled the system of Government with the whole kingdom against him and no one Person to support him but the Elector.Footnote43

In early July, the Palmerstons left Milan and continued north to Switzerland with their children going to Berne, while Blagden made his way back to England. Rumford had made such an impression on them that even their eight-year-old son, Henry John Temple, asked to be remembered to him,Footnote44 while in his letters to Palmerston Rumford soon began using the nicknames “wild one” and, slightly later, “butterfly” for her daughters. These appear to be of his own coining and illustrate just how close the friendship had already become.Footnote45 Rumford remained in Italy visiting Turin and Genoa, returning to Milan in late September. There he waited a week for the Palmerstons to arrive from Switzerland, before needing to depart for Desenzana, a resort at the southern end of Lake Garda on the road to Verona, to see his current mistress, Paumgarten’s sister, Magdalena, Comtesse Nogarola. The Palmerstons arrived back in Milan so soon before Rumford’s departure that he had already written to Viscountess Palmerston explaining his need to depart, the first of his surviving letters to her.Footnote46

The Palmerstons followed Rumford to Verona where they met Nogarola whom Viscountess Palmerston described as “his amee who I felt much acquainted with tho’ I had never seen her before. She is not handsome, but has fine eyes & a softness in her manner,” suggesting that Rumford had been quite explicit to Palmerston in describing their relationship.Footnote47 Rumford was not only continuing his affair, but working on improving the kitchens of some of Verona’s public institutions which he urged Palmerston to see (letters 4 and 5).

At Verona Viscount Palmerston made a “sudden resolution to spend another winter at Naples.”Footnote48 So Rumford and the Palmerstons headed south until Florence where Rumford left them to visit Lucca, Pisa, and Livorno,Footnote49 before re-joining them in Rome where they found him “settled in the same House with us.”Footnote50 The week before Christmas, the Palmerstons left Rome and headed to Naples where they were joined by Rumford early in the new year.Footnote51 In Naples they did the usual things, socialising, ascending Vesuvius, etc.Footnote52 Rumford became ill there, but was fortunate in receiving the attention of the Oxford University trained physician Edward Ash who was on the Continent as a Radcliffe travelling fellow. Viscountess Palmerston, to the dismay of one of her correspondents, decided to delay their departure from Naples, until Rumford had recovered.Footnote53 So it was not until sometime in April that the Palmerstons and Rumford left Naples, the latter returning to Verona and the former making their way to Venice (letter 4).

Rumford spent May and early June in Verona where he continued putting into practice some of the ideas he had developed in Munich on fuel efficiency, particularly related to cookery. He advised the hospitals of La Pietà and La Misericordia on how to save fuel in cooking meals for the 800 or more of the poor housed by them. He claimed that by using his designs, the hospitals could save nearly 90% of the wood used in cooking and he oversaw the construction of their new kitchens.Footnote54 Towards the end of June 1794 Rumford returned to Munich where he was joined in July by the Palmerstons.Footnote55 They spent ten days on a tour to Salzburg including visiting the brass works at Rosenheim, various salt works, Königsee, Berchtesgaden, and so on.Footnote56 They then left Rumford in Munich and made their way back to England arriving in October.

Rumford in England

Rumford’s political position in Munich remained difficult as he described to Palmerston (letter 12), so it was not long before he began planning to visit England for the first time in eleven years, claiming to her that the political machinations at Munich were too much for him (letter 16). By mid-August 1795, the Elector had granted Rumford permission to visit London from mid-September until the end of April (letter 18). Rumford took advantage of this opportunity to start publishing his ideas in a series of Essays and also, as in Verona, to apply his ideas practically in Britain. He wrote ahead to Palmerston asking her to order materials (bricks, mortar, etc.) so that his fuel-saving ideas could be implemented in her houses at Broadlands, Sheen and, presumably, her London town house (letter 18). Rumford had described to Palmerston some of his later experiments made following his return to Munich (letter 12), but nothing to suggest the results should be applied in her houses, which may imply that they discussed this while in Italy and Munich or in some letters that are missing.

Rumford’s arrival in London on the evening of Tuesday 13 October 1795 was noted in both the London and provincial press with a puff emphasising his critical importance to the government of Bavaria during the previous ten years.Footnote57 His first experience in London was unwelcomed as he was promptly robbed when the trunk on the back of his carriage containing his papers – “the labours of my whole life” – was cut off.Footnote58 He offered a ten guinea reward for the return of the papers which had limited success; in early November Viscount Palmerston reported that some papers had been found and returned, though not Rumford’s important common place book, adding that some of the “most valuable Papers were not in the Trunk.”Footnote59 Despite this apparent disaster Rumford, who brought a letter from the Elector to the King (letter 20), was presented at court the following day.Footnote60 He then spent part of the second half of October at Broadlands (letter 23).

Shortly after his return to London, where he stayed at the Royal Hotel, Pall Mall, something happened which deeply angered and offended him. In a series of three letters to Viscountess Palmerston in early November, Rumford vented his emotions: “Never surely was a human being exposed to so much unmerited persecution,” “But here alass! there is no protection for me. No peace, but in the grave,” “I dont know against whom I ought to vent my Rage,” “You can have no conception how much I am disgusted with every thing I see and hear,” “I plainly perceive that all ranks of Society have made a most visible progress in corruption during the twelve years I have been out of the Country,” “I hate mankind with a most perfect hatred,” and so on.Footnote61 However, by the time he wrote the third letter he had calmed down “and the black clouds which obscured my imagination are in a great measure dispelled” (letter 26). This seems to be related to some suspicions he had about Banks’s attitude towards him noted, but dismissed, by Blagden.Footnote62 Whatever the issue, Rumford certainly did not want to provide details on paper, even to Palmerston, though he wrote he would explain to her “more fully when we meet” (letter 26).Footnote63

Despite the difficulties, he seems to have enjoyed considerable prestige during his stay in London interacting with the elite of varying political persuasions. The strong Whig Dowager Countess Spencer invited him to dine at St Albans and to meet her daughter, Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, the latter having scientific interests.Footnote64 That occasion resulted in Spencer sending the architect Henry Holland to him which Rumford noted in his second emotional letter (letter 25), and meeting them a little later at Chiswick House.Footnote65 He dined with Blagden at Matthew Montague’s and with Ralph Payne, Lord Lavington (in the Irish peerage), MP for New Woodstock, who had been a Whig but by 1795 supported the Prime Minister William Pitt.Footnote66 And on St Andrew’s day Rumford was elected a member of the Council of the Royal Society of London, illustrating his good standing with Banks and Blagden,Footnote67 despite only being in England until the following April. Although that covered most of the Society’s active year, Rumford only attended once, on Christmas Eve.Footnote68 He also dined twice at the Society’s Club.Footnote69

In mid-March 1796, following her mother’s death, Rumford’s twenty-one-year-old daughter, whom he had not seen for nearly two decades arrived in London from America () (letter 33). She did not stay with her father at the Royal Hotel, but nearby with his agent, Charles Lackington, and his wife.Footnote70 Initially Rumford was delighted, but problems soon emerged centring on the state of her education, for example, her lack of French, her expenditure on clothes and her lack of social grace.Footnote71 In a letter to Palmerston, Rumford accused his daughter of indolence (letter 35). Thompson later recollected that she overheard Palmerston telling Rumford that Thompson did not admire much in London, to which he replied that “savages” did not take notice of such things; unsurprisingly Thompson complained strongly to Palmerston about this slur.Footnote72

FIGURE 7 Moritz Kellerhoven, portrait of Sarah Thompson (1797). Courtesy of the Historical Society of New Hampshire, 1979.020.07.

Experimental essays

Rumford kept busy in the closing months of 1795 and the beginning of 1796 with publishing and presumably, because of the theft, rewriting some at least of what would become his Experimental Essays, Political, Economical, and Philosophical. Aside from the few contributions he had made to the Philosophical Transactions since his gunpowder paper of 1781 and his 1792 pamphlet on the reform of the Bavarian army, Rumford had published hardly anything and, as he freely admitted to Palmerston, did not know how to set about publication (letter 21). After visiting Broadlands in October, he got down to the serious business of seeing his writings through the press with the help of John Baker Holroyd, Lord Sheffield (in the Irish peerage), MP for Bristol, whom he had certainly met by 1783 when Sheffield helped him obtain an army promotion.Footnote73 During 1795, Sheffield was editing the works of his recently deceased friend, the historian Gibbon. These two volumes would be published the following year by Cadell and Davies and it was doubtless this connection that led to Rumford’s Essays being produced by the same firm.

The Essays were first published as a series of separate octavo pamphlets, usually around a hundred pages long and consecutively paginated. They were so well received and popular that they quickly went through many printings (and translations). From the start, it was intended that the pamphlets would be collected together into bound volumes retaining their original pagination. Their publication history is thus complicated and here is not the place to go into full detail except as related to Rumford’s letters to Palmerston. Cadell and Davies received the manuscript of the first Essay, An Account of an Establishment for the Poor at Munich, in mid-November 1795Footnote74 and a month later the first two volumes were advertised, listing the intended titles of the first ten Essays, though making it clear that each Essay would be issued separately, attributing this action to the “Subjects [being] highly interesting at the moment.”Footnote75 The first Essay, published on Christmas EveFootnote76 was, as he told Palmerston, well-reviewed in the February issue of The Critical Review (letter 28). William Petty-Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquis of Lansdowne (1737–1805) agreed that Rumford’s proposals had “great merit.”Footnote77

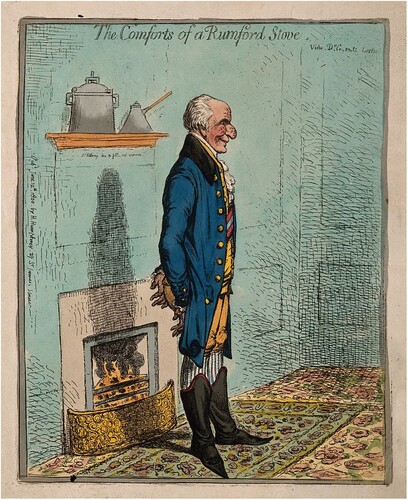

During this period, as his letters and Blagden’s diary illustrate, Rumford was pursuing a very active social life in London high society. Indeed, Palmerston’s husband told her how distracted Rumford was at this time.Footnote78 Furthermore, he found time during this period to experiment at the Palmerstons’ Hanover Square townhouse on improving domestic fireplaces so that they would not smoke into the room, an issue, it seems he had not considered before.Footnote79 It appears that the immediate occasion for him looking into the matter was due to the problems created by the remodelling, undertaken by Holland, of the Palmerstons’ house. This project had begun towards the end of 1794 and early the following year it was found that the fireplaces were smoky.Footnote80 At some point, probably towards the end of 1795, Rumford undertook experiments on the fireplaces, some of which he seems also to have performed in the Royal Hotel.Footnote81 He developed a shape for the entry point from the fireplace to the chimney that ensured the smooth (and irreversible) flow of smoke upwards which was very easy to implement.Footnote82 His design was first tried in practice by altering two chimneys in the Whitehall house of John Sinclair (1754–1835) which also accommodated the offices of the Board of Agriculture of which Sinclair was President.Footnote83 As Rumford fully realised installing the fireplaces at the Board of Agriculture ensured that they would be seen by many prominent people and the same presumably went for the Royal Society of London’s offices in Somerset House.Footnote84 Indeed, the aristocratic seats and townhouses he listed in his Essay as having installed his fireplaces was impressive. They included, in addition to the Palmerstons, the Devonshires, Spencers, Bessboroughs, Melbournes, and Salisburys among others. In total Rumford claimed that 150 fireplaces in London alone had been altered during the previous two months.Footnote85 Clearly, Rumford did not personally oversee all these installations, but some he did, such as at Sheffield’s Sussex seat where he spent a week turning the house “topsy turvy” as Sheffield’s daughter told a friend.Footnote86 Such an effective modification to domesticity soon attracted caricaturists’ attention who emphasised the alleged comforts entailed for both sexes ().Footnote87

FIGURE 8 James Gillray, The Comforts of a Rumford Stove (London: Hannah Humphrey, 1800). Wellcome Collection 9160i. Public Domain.

It would not be surprising given all this that Rumford was behind with his writing. Just before Christmas, he told Palmerston that before he could visit her he must complete a few chapters of his second essay, Of the Fundamental Principles on which General Establishments for the Relief of the Poor may be formed in all Countries (letter 27). The text was with the publishers early in the new yearFootnote88 and there is no evidence that Palmerston minded this neglect. The second Essay was advertised in mid-FebruaryFootnote89 and shortly afterwards Rumford was expecting the appearance of his third Essay (letter 31), On Food, which introduced the world to his famous/notorious soups.Footnote90 That did not prevent him from asking Palmerston for her recipe for noodles (letter 32) which may have been included towards the end of the Essay which was not published until the second half of March.Footnote91

In February, Rumford received a letter from Sinclair asking him to publish his work on fireplaces as soon as possible.Footnote92 Rumford obliged and altered the plan of his Essays so that the fourth Essay, Of Chimney Fire-Places, which had not originally been included in the topics to be covered, was published in mid-April.Footnote93 Rumford completed the fifth Essay, again not in his initial plan, A Short Account of Several Public Institutions Lately formed in Bavaria, in July. With five Essays now published it was time to gather them into a single volume, which curiously dropped the word “Experimental” from the title.Footnote94 Rumford dedicated the volume to the Elector on 1 July; two weeks later, evidently highly relieved at the end of the project, he told Palmerston that he had just completed the work (letter 36) which was shortly published.Footnote95 Soon afterwards, Rumford left London to return to Bavaria (letter 37).

Back in Munich, Rumford continued writing his Essays, and towards the end of January 1797 sent his sixth and, as he appreciated, at nearly 200 pages the longest, to his publishers.Footnote96 By April 1797 Of the Management of Fire, and the Economy of Fuel was being printed, while he had just completed the seventh, Of the Propagation of Heat in Fluids, (letter 45), though he did not send it to Cadell and Davies until the following month;Footnote97 Essay six, published in early May,Footnote98 had been in his initial plan whilst the first part of number seven, which appeared towards the end of June,Footnote99 had not. References to later Essays in the letters are few and far between though he did tell Palmerston he was working on new ones (letter 55) and presented her with a copy of Essay X (letter 60).

Reaction to Rumford’s Essays was generally positive. Both London and provincial newspapers extracted sections from the third Essay, particularly on barley, suggesting that this Essay at least was well thought of.Footnote100 So it is perhaps not too surprising that shortly after the publication of the second Essay, Rumford told Palmerston triumphantly of the wide-spread and enthusiastic support he had received “for making the Poor comfortable and happy.” Among those who agreed to help, he claimed, was William Wilberforce, MP for Yorkshire, who personally undertook to introduce his ideas in London and would arrange a meeting with Pitt (letter 30). Indeed, the following week Wilberforce told Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) that he was interested in pursuing the idea of Rumford’s plan for “working rooms.” However, Bentham also noted that Wilberforce acknowledged that there was not much in Rumford’s Essay on the poor, which seems to contradict Wilberforce’s interest in applying some of Rumford’s ideas. It is, however, possible that Bentham’s phraseology reflected his own opinion rather than Wilberforce’s.Footnote101 Although Bentham had sent Rumford a copy of his Panopticon: or, the Inspection-House (1791),Footnote102 he did not reference any of Bentham’s works in the first two volumes of his Essays, since in many respects their ideas were in opposition.Footnote103 Nevertheless, when developing his unpublished utopian schemes on pauper management in the latter half of 1797, Bentham extravagantly praised Rumford as the person best fitted to implement them.Footnote104

Rumford in Dublin and the Bettering Society in London

Another who thought highly of Rumford’s ideas was Thomas Pelham MP for Sussex who had been appointed Chief Secretary in Ireland in March 1795 and who in June 1796 would also become Secretary of State for Ireland. They were possibly introduced by Sheffield, Pelham’s brother-in-law. Although Rumford should have returned to Munich at the end of April, instead he told Palmerston of the arrangements being made for him to visit Ireland during May. These included him living in Pelham’s house in Phoenix Park and the provision of an office in Dublin Castle, the seat of government in Ireland (letter 34). Leaving his daughter at a boarding school in Barnes run by French émigrés,Footnote105 by 3 May Rumford, writing from Dublin, told Sheffield of the favourable reception he had received in Ireland.Footnote106

Although during his month or so in Dublin Rumford concentrated on economical cooking, he also exhibited his boiler at the Linen Hall to reduce the costs of bleaching.Footnote107 At the House of Industry which had a capacity of 1500 people,Footnote108 Rumford, working with Pelham and a couple of prominent Irish politicians, made various suggestions for its improvement.Footnote109 The politicians were the Irish Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Parnell (1744–1801), and the Speaker of the Irish House of Commons, John Foster (1740–1828). Foster almost immediately thanked Sheffield for introducing RumfordFootnote110 and, towards the end of June, told him that Rumford had won “the admiration of all ranks” in Dublin, and had undertaken a great deal of work, though more remained to be done.Footnote111 His efforts were formally recognised by an address from the Grand Jury of County Dublin (which also thanked Pelham for bringing Rumford there)Footnote112 while the Dublin Society awarded him a twenty (Irish) guineas gold medal and the Corporation of Dublin granted him the Freedom of the City.Footnote113

On his way back to London from Dublin at the end of May, Rumford visited Birmingham where he met James Watt sr who, despite the cancelled steam engine order, commented favourably on him and they experimented together on lining copper pans with silver.Footnote114 Back in London Rumford pursued activities similar to those in Dublin but did not receive any civic recognition. He designed kitchens for various locations such as Sinclair’s Whitehall house which was open to public inspection.Footnote115 Other institutions that received Rumford’s attention included the workhouse of St George’s Hanover Square Parish in Mount Street which with 700 occupants was one of the largest in EnglandFootnote116 and the kitchen of the Foundling Hospital whose Treasurer was Thomas Bernard.

It is faintly possible that Rumford and Bernard had met previously when they were teenagers in Massachusetts or young men in London in the late 1770s, but no direct evidence exists that supports such an acquaintance. However, they met, Bernard later wrote that “a similarity of pursuits produced a considerable Intimacy between us.”Footnote117 But it was not until March 1796 that Rumford was invited to assist the implementation of his ideas in the Foundling’s kitchen with the aim of saving fuel and thus expense, something always dear to a treasurer. However, owing to his visiting Ireland and then Sheffield Place, Rumford was unable to oversee the work personally. So, when he returned to London in July, he found that the builders had completely misunderstood his instructions which entailed “pull[ing] down the kitchen and rebuild[ing] it.”Footnote118 Nevertheless, the final result well satisfied the Hospital’s matron, Hannah Johnson, and Bernard. Although the work cost £150, more than 70% in fuel was saved over a year and one less cook was employed.Footnote119

That Rumford could not oversee the new building work was due to being recalled to Munich following the French invasion of the German states at the start of June. On 13 July, he took leave of the KingFootnote120 and shortly thereafter began his circuitous journey to Munich taking his daughter with him. There she pursued an active and enjoyable social life,Footnote121 the Elector creating her Gräfin Rumford (letter 40), though by the summer of 1797 she was clearly so homesick that Rumford took to calling her “the American” (letter 48). The Elector appointed her father commander of the Bavarian army with the task of defending Munich from the opposing Austrian and French armies who were converging on the city in the late summer of 1796. In a spectacular feat of diplomacy, Rumford kept both sides talking until the French army was required elsewhere, upon which the Austrians also withdrew.Footnote122

Despite his absence, Rumford’s ideas continued exerting influence in Britain. During the summer of 1796, the possibility of forming “a society for encouraging the industry and promoting the welfare of the poor” was discussed by Bernard, Wilberforce, Edward James Eliot (1758–1797) and Shute Barrington (1734–1826), Bishop of Durham since 1791.Footnote123 The outcome was a circular letter dated 17 December 1796 proposing the formation of a “society for bettering the condition and increasing the comforts of the poor” and calling a meeting for the afternoon of the 21st.Footnote124 Whilst this letter referred to specifically English problems, such as parochial relief and workhouse abuses, it stressed that in improvements to fuel, food, and helping the poor generally “the world is indebted to the philanthropy and abilities of Count Rumford.”Footnote125 The chief object of the Bettering Society (as it was universally called) was to collect examples of best practice for helping the poor and publishing the results in a series of Reports. This Baconian approach promoted, as the letter put it, that “most beneficial of all sciences – the promotion of the welfare of our fellow-creatures” – a view surely again influenced by RumfordFootnote126 who was elected a Life Member of the Society on 24 February 1797.Footnote127 In his letter of thanks, Rumford suggested that the Society would be improved by using models that could be “seen and felt.”Footnote128

Rumford, who later contributed one report,Footnote129 as might be expected, received a major share of credit throughout the first three volumes of the Reports for his practical contributions. His innovations both material and social were mentioned with great acclaim in a number of articles, including those by Bernard,Footnote130 Pelham,Footnote131 George Finch, 9th Earl of Winchilsea,Footnote132 and William Hillyer (a contractor to the Foundling);Footnote133 while Barrington in his report on the poor at Hamburg attributed the success there entirely to Rumford’s example at Munich and his conclusion provides an indication of the esteem in which Rumford was held:

That which has been done in Hamburgh, by the co-operation of its best and wisest citizens, has been effected at Munich by the abilities of perseverance of one individual. The particulars of that establishment are so well and so generally known, that it is unnecessary for me to enter into the detail of them. The institution has, in both instances, been wisely adapted to the circumstances and condition of the respective places; at Munich with additional power, from the establishment being blended with the government of the state, and producing an influence of the country, of what that city is the capital; and from its being connected with a variety of useful, and extraordinary inventions and improvement which Count Rumford has made, and is now making, for the benefit of mankind.Footnote134

The Royal Institution

After his success in preventing the military occupation of Munich, Rumford resigned command of the Bavarian army to concentrate on his research. In a letter accompanying a long paper on gunpowder for the Royal Society of London,Footnote135 he told Banks “my power <is> undiminished” but that he was now “master of my time, and devote it almost entirely to my literary pursuits”Footnote136 which would probably have struck Banks as contradictory. During 1797, Rumford certainly focused on writing his Essays (detailed above) and started experimentation on cannon boring that would lead to his paper on the production of heat by friction. In this paper, he argued against the materiality of heat, specifically the caloric proposed by Antoine Lavoisier, and instead proposed that heat was a mode of motion.Footnote137 Towards the end of the year, Rumford began suggesting to the Elector that he should be appointed Bavarian ambassador to Britain, writing to Banks asking him to find out how that proposal would be received in London.Footnote138 It is not known if Banks made any enquiries, but Rumford later claimed that he had been “promised the most gracious reception” (letter 53). However, Rumford could not then immediately pursue this scheme for at the end of the year there were revolutionary disturbances in Swabia and Mannheim. The Elector returned Rumford to command of the army and additionally appointed him chief of police with “ample powers.”Footnote139 Despite the crisis, Rumford continued to manage his research and writing, by, for example, sending his eighth Essay to London for printing.Footnote140 By the summer, the political crisis had passed and in June Rumford was able to take a fortnight’s holiday with his daughter.Footnote141

In August 1798, the Elector fulfilled Rumford’s ambition by appointing him Bavarian ambassador to London.Footnote142 Rumford’s annual income in this role would be £2000, or twice what he was currently earning.Footnote143 He also saw moving to London as the first step in paving the way for his daughter, and possibly himself, to return to America (letters 47 and 50). That he regarded the move to London as permanent is evinced by arranging for all his books, papers and other possessions to be taken there (letters 53 and 54).

Rumford’s arrival in London the following month, provoked a minor diplomatic incident. An hour after he had arrived at the Royal Hotel, on 19 September, George Canning, a junior Foreign Office minister, visited Rumford to tell him that the King would not accept him as ambassador.Footnote144 Rumford, though very angry, sought to resolve the matter as quietly as possible, by offering his resignation on the grounds of ill health and asking for permission to visit America in the spring of 1799. To both requests, the Elector agreed (letters 54 and 56). A replacement ambassador, however, did not arrive until a couple of years later,Footnote145 presumably due to the death of the old Elector on 16 February 1799 and the succession of Maximilian Joseph.

In the meantime, Rumford looked for somewhere to live and in late October moved into 51 Brompton Row on the western outskirts of London.Footnote146 He rekindled his old contacts, for example with Bernard, who took him to the Foundling Hospital to show him the kitchen that Rumford had been working on before his recall to Munich (letter 54). But on the whole, he seems to have been at something of a loose end. Palmerston’s husband suggested that he had taken to drink and he visited Bath over the new year, calling in at Broadlands on his way back to Brompton.Footnote147 However, Rumford during this period had been working on a plan to establish the kind of practical institution in London that he had hinted at when elected a Life Member of the Bettering Society. Nevertheless, at the end of January 1799 Rumford was apparently still intending to sail to America at the start of March.Footnote148 But on the last day of January, he attended a meeting with those closely associated with the Bettering Society where he presented the “Proposals” he had drawn up for a new institution. Whether he believed that the plan could be implemented without his presence in London is not clear, but two days later he wrote to Palmerston summarising what was intended writing it “may prevent my intended journey to America” (letter 58). And by mid-February Rumford had concluded that he was likely to remain in England.Footnote149

He did, indeed, remain in London while his daughter returned to America in August.Footnote150 Rumford spent the next three or so years working, off and on, to establish what became the Royal Institution of Great Britain. Here is not to place to detail this story, about which much has been written.Footnote151 But Rumford’s letters to Palmerston do reveal a couple of aspects to the story that seem not to have been previously noticed. First, the letters show that Rumford met in Italy a number of men who would become Proprietors (subscribing the substantial sum of fifty guineas), Life or Annual Subscribers (who both paid significantly less) of the new institution and so contributed to making it a going concern. These included Edward Ash, 2nd Earl Camden, 2nd Earl Digby, Andrew Douglas, Gilbert Elliot, Matthew Montagu, Viscount Morpeth, Viscount Palmerston, James Archibald Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie, Charles Talbot and, though not in Italy, Thomas Pelham. Furthermore, the letters also show Rumford’s previous connections with a number of women who would become “distinguished patronesses” of the Royal Institution. These included the Countess of Bessborough, the Duchess of Devonshire and Viscountess Palmerston.Footnote152 Right from the start Palmerston took a strong interest in the new Institution telling her elder son it was going well and providing a long description of it shortly after its lecture programme commenced in March 1800.Footnote153 As so often with new institutions, pre-existing connections and networks, especially as I have argued elsewhere during this period aristocratic ones,Footnote154 became critical to successfully bringing them into existence. The second aspect relates to the large lecture theatre built at the northern end of the gentleman’s townhouse in Albemarle Street acquired by the Institution for its house in the summer of 1799. The theatre, which on occasion could hold a thousand people, was designed by the Clerk of the Works, Thomas Webster (1772–1844).Footnote155 But the inspiration for its semi-circular, raked, amphitheatre form may have come from the theatre that Rumford had had built in Munich’s Englisher Garten in turn derived from the Roman theatre in Verona. Although there is no documentary evidence for such a suggestion, the enthusiastic way Rumford described the Munich theatre to Palmerston (letters 15 and 16) does at least render it a possibility.

Rumford’s work for the Royal Institution did not mean he entirely neglected Palmerston. Although there are no surviving letters from Rumford to her between November 1799 and August 1801, there is evidence of close personal contact during that period which may have obviated the need for correspondence. Over the new year 1799/1800, having arranged for the components of a kitchen for her School of Industry that she was establishing in Romsey to be delivered, he stayed there for most of January to help out.Footnote156 It became apparent during the year that Palmerston’s collaborators lost interest and by the start of 1801 she had taken the school under her own control with successful results, at least according to her husband and her letters to a relative.Footnote157 Possibly Palmerston’s initial lack of engagement was due to her in late 1800 taking her son, Henry John Temple, to Edinburgh to study at the University. By then, in a scenario strongly reminiscent of their journeys around Italy, Rumford too was in Edinburgh having left London in mid-July for Harrogate and indeed there was some discussion about the Palmerstons meeting him there which came to nothing.Footnote158 In September Rumford arrived in Edinburgh, where among other things, he fitted up a kitchen in Heriot’s hospital for children.Footnote159 The Palmerstons arrived in mid-October having spent the previous month making a leisurely tour northwards.Footnote160 After a few days, they went on a tour of Scotland returning to Edinburgh where they settled their son in during early November. They left the city on the 10th taking Rumford with them, reaching London on the 20th.Footnote161 Rumford arrived back in time for the completion in early 1801 of the lecture theatre and the opening course of lectures delivered by Thomas Garnett (1766–1802), which Palmerston and her daughters attended “pretty constant[ly].”Footnote162

Until September, Rumford seems to have spent all of 1801 in London. He then decided or was asked to visit Munich to discuss his future role in Bavaria (letter 62). Equipped with a passport from the French diplomatic representative in London negotiating the Preliminaries of what would become the Peace of Amiens, Rumford set off via France to spend most of October in Munich where he received a good reception from the new Elector (letter 63). Throughout this Continental journey, Rumford kept a detailed diary which at some point he gave to Palmerston. Between 29 April and 4 May 1802, she copied this to ward off her “ceaseless Sorrow” following the death of her husband on 16 April.Footnote163 With the signing of the Preliminaries, the Elector instructed Rumford, on his way back to London, to visit Paris with despatches for the Bavarian ambassador there. Arriving at the end of October 1801, Rumford remained in Paris until mid-December. In both his letters and diary, he described his mixing with the French governing elite including the First Consul Napoleone Buonaparte for whom Rumford expressed admiration for the anti-democratic stance now dominant in France (letter 66). During his stay, he met Marie-Anne Lavoisier, widow of the chemist Antoine Lavoisier, guillotined during the Terror for being a tax farmer.Footnote164 He later called on her a couple of times during his remaining time in Paris.Footnote165 It may have been meeting her that led to Rumford extending his visit to Paris, since the previous week he had told Pelham that while he would like to stay, he was needed at the Royal Institution.Footnote166

By this time whether Rumford was needed at the Royal Institution was a matter of differing opinions. It is not clear precisely what was the origin of the problem, but by the beginning of 1802, the Institution was at the start of what would be the first (of many) financial crises. Rumford seems to have been blamed and towards the end of February was making preparations to leave London for Paris and presumably the attractions of Lavoisier.Footnote167 However, he carried on the normal work of the Royal Institution until 9 May when he left London, never to return.Footnote168 Palmerston’s view of Rumford’s problems at the Royal Institution showed her loyal to the last, recording in her diary on 21 May 1803 that “Their abuse of Count R is atrocious.”Footnote169

End of the affair

Rumford spent the latter part of the 1802 in Munich, but clearly wanted to be back in Paris with Lavoisier. In the end, she joined him in BavariaFootnote170 and they seemed to have spent most of 1803 touring Europe, but by November both were back in Paris.Footnote171 Early the following year, Rumford informed his daughter that he was intending to marry and listed all of Lavoisier’s virtues concluding “in short, she is another Lady Palmerston.”Footnote172 After sorting out some legal problems, Rumford and Lavoisier married on 24 October 1805.

The death of Viscount Palmerston, Rumford’s departure from the Royal Institution and London and his affair and marriage with Lavoisier all seem to have contributed to a diminution in the flow of letters in these years between Rumford and Palmerston or possibly in her grief she did not retain them. Certainly, Rumford wrote soon after he arrived in Paris to say he was pleased with the city.Footnote173 It is probably not coincidental that shortly after Rumford told his daughter about his intended marriage his letters to Palmerston resumed with the final three all written in 1804. They included discussion of the practical issues involved in the marriage, but one concluded with a rather tactless comment:

I think I shall live to dive drive caloric off the stage as the late M. Lavoisier (the author of caloric) drove away Phlogiston. What a singular destiny for the wife of two Philosophers!! (letter 67)

Perhaps this episode was an instance of the sturm-und-drang quality, identified by Linda Colley, in the lives of the British elite from the start of the American rebellion to the final defeat of France in 1815.Footnote175 Possibly this tendency was magnified in Rumford’s case by his not really being part of that elite – in total he only spent eight years of his life on those islands. Rumford was one of those people who was seldom content or happy wherever they might happen to be, in his case North America, London, Munich or, later, Paris: “an exile doomed to roam in the wide world, without a home, and without a friend” as he wrote to Palmerston in late 1793 (letter 2). Whatever he did, he felt he never enjoyed the high level of recognition that he believed he deserved and in the case of Munich had had to cope with the intrigues of the Bavarian court – the source of the paranoia displayed in many of his letters?

Without her letters to him, we don’t know whether Palmerston appreciated any of this. She did not live to see either Rumford’s marriage or its breakdown, dying on 19 January 1805. Rumford’s comment that Lavoisier was a second Palmerston is fascinating, suggesting that had Rumford and Palmerston consummated their relationship, it might possibly have ended in a similarly disastrous manner. On that basis, Palmerston was surely wise in keeping significant distance between her and Rumford. It allowed them, as a closer relationship might not, to correspond freely for over a decade giving us a remarkable insight into their complex social and political worlds of which the production and communication of scientific knowledge was just one part.

Abbreviations and contractions

| Manuscripts | ||

| BL | = | British Library |

| PRONI | = | Public Record Office of Northern Ireland |

| RI | = | Royal Institution |

| RSL | = | Royal Society of London |

| SU | = | Southampton University |

| TNA | = | The National Archives |

| UBCRL | = | University of Birmingham Cadbury Research Library |

| Printed sources | ||

| Reports SBCP | = | The Reports of the Society for Bettering the Condition and Increasing the Comforts of the Poor |

| Rumford’s Essays (all published London: Cadell and Davies) | ||

| Essay I | = | An Account of an Establishment for the Poor at Munich (1796) |

| Essay II | = | Of the Fundamental Principle of which General Establishments for the Relief of the Poor may be formed in all Countries (1796) |

| Essay III | = | Of Food; and particular of Feeding the Poor (1796) |

| Essay IV | = | Of Chimney Fire-Places (1796) |

| Essay V | = | A Short Account of Several Public Institutions Lately formed in Bavaria (1796) |

| Essay VI | = | Of the Management of Fire, and the Economy of Fuel (1797) |

| Essay VII | = | Of the Propagation of Heat in Fluids (two parts, 1797–1798) |

| Essay VIII | = | Of the Propagation of Heat in Various Substances: Being an Account of a Number of New Experiments Made with a View to the Investigation of the Causes of the Warmth of Natural and Artificial Clothing (1798) |

| Essay IX | = | An Experimental Inquiry concerning the Source of the Heat which is excited by Friction (1798)Footnote176 |

| Essay X | = | On the Construction of Kitchen Fire-Places and Kitchen Utensils, together with Remarks and Observations relating to the various Processes of Cookery; and Proposals for improving that most useful Art (1799) |

| Biographical Sources | ||

| AC | = | Alumini Cantabrigienses |

| ADB | = | Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie |

| ANB | = | American National Biography |

| Bourne | = | Kenneth Bourne, ed., The Letters of the Third Viscount Palmerston to Laurence and Elizabeth Sulivan 1804–1863 (London: The Royal Historical Society, 1979) |

| BU | = | Biographie Universelle |

| CP | = | Cokayne, Complete Peerage |

| DBF | = | Dictionnaire de Biographie Française |

| DBI | = | Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani |

| DHS | = | Dictionnaire Historique de la Suisse |

| GM | = | Gentleman’s Magazine |

| HP | = | History of Parliament |

| Ingamells | = | John Ingamells, A Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy 1701–1800 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997) |

| LUI | = | Lessico Universale Italiano |

| Munk’s Roll | = | Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of London |

| NDB | = | Neue Deutsche Biographie |

| ODNB | = | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |

Provenance

Following the death of Viscountess Palmerston in 1805, these letters were retained in the family archive at Broadlands. Through marriages, via the Ashley family, the house and contents passed in 1939 to Edwina Ashley (1901–1960), the wife of Louis Mountbatten (1900–1979), later The Earl and Countess Mountbatten of Burma; Broadlands remains the family seat. Extracts of some of these letters from Rumford as well from many other correspondents in the archive were quoted in Brian Connell, Portrait of a Whig Peer Compiled from the papers of the Second Viscount Palmerston 1739–1802 (London: Andre Deutsch, 1957).Footnote177 By then letter 58 had been given to the Royal Institution in 1899 on the occasion of the centenary of its founding.Footnote178

By the late 1940s, the plasma physicist Sanborn Brown (1913–1981) who graduated from Dartmouth College, but spent his career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had begun his life-long study of Rumford.Footnote179 He was assiduous in his search for material relating to Rumford as the notes to his biography published in 1979 testify. This included acquiring manuscripts and at some point he purchased from the Mountbatten family sixty-seven letters from Rumford to Palmerston “which had just been offered for sale at a price our family budget could ill afford.”Footnote180 He later gifted them to Dartmouth College along with other Rumford-related material.

Brown’s purchase presumably occurred before the death of Countess Mountbatten in 1960, since shortly afterwards Earl Mountbatten deposited the Palmerston papers in the Hampshire Record Office, Winchester.Footnote181 The papers remained there until the second half of the 1980s when they were transferred, also on deposit, to the University of Southampton. In 2010, after a major fund-raising effort, the University purchased the collection, together with Mountbatten’s own papers, from the estate for £2.85 million. Among those papers is letter 43 that evidently escaped Brown’s attention and so did not make it across the Atlantic.

Biographical register

This provides details on those who are mentioned three or more times in the sixty-nine letters. This list is alphabetised by the name in each entry appearing in bold small capitals. The inclusion of an individual in the register is signified in the letters or in the notes by the name appearing there in small capitals. (Those who appear once or twice in the letters are identified only in the footnotes). Where no source is given, the information has been drawn from the usual genealogical databases.

Aichner. Rumford’s long-term valet, whose name Rumford frequently mis-spelt Eichner.Footnote182

Edward Ash (1764–1829, Munk’s Roll, Ingamells, 30). Physician who in early 1794 treated Rumford in Naples for which he was ever grateful. He successfully nominated Ash to Fellowship of the Royal Society of London (RSL MS EC/1801/13).

Charles Blagden (1748–1820, ODNB, Ingamells, 96–7). Physician and a Secretary of the Royal Society of London, 1784–1797.

Napoleone Buonaparte (1769–1821, BU). French general and, as First Consul of France, 1799–1804, military dictator of France and the territories it occupied.

Mary Carter (bp.1731ns–1812, Ingamells, 187). Viscountess Palmerston’s companion.Footnote183

Anton Cetto (1756–1847, NDB). Bavarian ambassador to Paris.

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744–1818, ODNB). Queen of England as wife of George III whom she married in 1761.

Sarah Culverden, née Mee (bp.1748, d.1810, GM 80(2) (1810): 392). Sister of Viscountess Palmerston. Married in 1767 the banker William Culverden (d.1811, GM 81(1) (1811): 494).

Georgiana Cavendish, née Spencer, Duchess of Devonshire (1757–1806, ODNB, Ingamells, 295–6). Daughter of Dowager Countess Spencer and a leading figure in London high society and Whig politics.

Johann Georg Dillis (1759–1841, NBD). Bavarian artist and Roman Catholic priest. He undertook a number of painting commissions for Palmerston, for which Rumford acted as a go between. While they were in Munich, he also portrayed the Palmerstons’ four children.Footnote184

Eichner see Aichner.

Gilbert Elliot (1751–1814, ODNB). 4th Baronet and later 1st Earl of Minto, Politician and later diplomat and colonial governor. At this time Viceroy of Corsica.

George III (1738–1820, ODNB). King of England, 1760–1820.

George Frederick Charles Joseph (1779–1860, NDB). Later (1816) Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

Amelia Elizabeth Godfrey, known as Emma (d.1840, Bourne, 46). Companion to Viscountess Palmerston and her sister; a life-long friend of Palmerston’s children.

Friederike Eleonore Sophie von Kalb, known as “Lore” or “Laura” (1764–1831). Another of Rumford’s mistresses. https://www.nhhistory.org/Object?id=0990305d-8362-44d4-90d5-755fdca3447f (accessed 22 February 2023).

Karl Theodor (1724–1799, NDB). Count Palatine from 1742 and from 1777 also Elector of Bavaria, both to death.

Charles Lackington (c.1740–1807). Rumford’s agent in London.

Marie-Anne Lavoisier, née Paulze (1758–1836, DBF). Widow of the guillotined French chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. She married Rumford, as her second husband, on 24 October 1805. They divorced in 1809.

Maria Leopoldine, Archduchess of Austria-Este (1776–1848). Became Electrice of Bavaria following her marriage to Karl Theodor on 15 February 1795 six months after the death of his first wife.Footnote185

Maximilian Joseph (1756–1825, NDB). Duke of Zweibrücken or Deux Ponts from 1795. Elector of Bavaria from 1799 until 1806 when, following the abolition of the Holy Roman Empire, he became King.

Benjamin Mee (bp. 1750–1796, GM 66(2) (1796): 706, 787). Palmerston’s brother, and a Director of the Bank of England, 1777–1783. He was declared bankrupt in 1784 which presumably accounts for his moving first to Bengal and then to the Continent. He died at Pyrmont.Footnote186

Elizabeth Mee, née Man (d.1796). Mother of Viscountess Palmerston.

Magdalena, Contessa Nogarola, née von Lerchenfeld-Siessbach-Prennberg (1770–1810). Lived in Verona. Friend and sometime mistress of Rumford and younger sister of Gräfin Paumgarten. https://www.nhhistory.org/Object?id=b8e055b4-6d87-4fc2-8a68-1f04c131f033 (accessed 22 February 2023).

Brownlow North (1741–1820, ODNB, Ingamells, 711–12). Bishop of Winchester, 1781–1820. Broadlands, located within the diocese, is about twelve miles from Winchester.

Maria Josepha Barbara Johanna Nepomucena Gabriele von Lerchenfeld-Siessbach-Prennberg, Gräfin Paumgarten, née von Lerchenfeld-Siessbach-Prennberg (1762–1816) (). Elder sister of Contessa Nogarola. Sometime mistress of Karl Theodor and later of Rumford by whom she had Sophia Paumgarten. Lived in Munich or nearby on Lake Starnberg. Her name is occasionally spelt beginning with a “B”. https://www.nhhistory.org/object/136514/painting (accessed 22 February 2023).

Walburga Sophia Barbara Paumgarten (1788–1828) (). Rumford’s natural daughter with Gräfin Paumgarten. It is not clear when, if ever, Palmerston became aware of the relationship. Her surname is occasionally spelt beginning with a “B”. https://www.nhhistory.org/Object?id=dc5dc813-0210-415a-822c-2708a54065a8 (accessed 22 February 2023).

Thomas Pelham (1756–1826, ODNB). MP for Sussex, 1789 to 1801. Thereafter sat in the Lords in his father’s barony until he succeeded (1805) as 2nd Earl of Chichester. At this time, Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Margaret Georgiana, Dowager Countess Spencer, née Poyntz (1737–1814, ODNB, Ingamells, 884). Widow of John, 1st Earl Spencer (1734–1783, ODNB), she travelled in Italy between 1792 and 1794 where she met the Palmerstons on a number of occasions.Footnote187

Henry Temple, 2nd Viscount Palmerston in the Irish peerage (1739–1802, ODNB, HP, Ingamells, 733–5). Husband of Viscountess Palmerston whom he married, as his second wife, in 1783. Connoisseur and Whig MP for various seats from 1762 until death.

Temple children:

Henry John Temple, later (1802) 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784–1865, ODNB).

Frances (Fanny) Temple (1786–1838).

William Temple (1788–1856).

Elizabeth (Lilly) Temple (1790–1837).

Therese of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1773–1839, NDB). In 1789, married Karl Alexander, later 5th Prince of Thurn and Taxis.

Sarah Thompson, Gräfin von Rumford (1774–1852) (). Rumford’s daughter by his first marriage. He did not see her from the time he left America in 1776 until she arrived in London in 1796. On her arrival in Munich later that year, Karl Theodor created her Gräfin (letter 40). Clearly homesick while in Europe, she returned to America in 1799.

Uriah. A senior officer in the Bavarian army and Rumford’s secretary, otherwise unidentified.

Whitworth, Miss (Bourne, 38). A close friend of the Palmerstons. A sister of Charles, Earl Whitworth (1752–1825, ODNB), but otherwise unidentified.

Anne Catherine Wilkinson, later Montagu, née Hobart (bp.1762–1800, Ingamells, 1002). The wife of Montagu Wilkinson (later Montagu), whom she married in 1784. They toured Italy with their children between 1791 and 1796.

Montagu Wilkinson, later (1797) Montagu (1744–1797, Ingamells, 1002, GM, 67(2) (1797): 616). Chief Clerk at the Signet Office.

Editorial conventions

[missing word(s) or letter(s)]

{reconstructed word(s) or letter(s), usually where the MS is torn}

<word(s) inserted above or below line>

To avoid the same words appearing twice in immediate succession, follow on words between pages have been silently omitted.

The letters of Reichsgraf von Rumford to Viscountess Palmerston

Apart from letters 43 and 58, all are in Dartmouth College, Rauner Special Collections MS 793528.

Letter 1: 28 September 1793

Auberge Imperial, Milan | Saturday Morning 28th. Sepr. 93.

I am very sorry to be obliged to leave Milan without waiting your Ladyships arrival,Footnote188 but having, upon my coming here, made arrangements with my friends at Verona to meet them at DesenzanaFootnote189 on Tuesday next, to dine, and as it is now out of my power to give notice to my friends of my wish to postpone that meeting, – the Post going from hence to Verona but once a week – it is absolutely necessary for me to set out upon my journey today. I sent forward my Horses and servants yesterday, and shall join them this Evening at Bergamo. I arrived here from Genoa on Saturday, last the 21st. Instant. My Servants and Horses arrived here from Como the day before. I found them all well.

I found letters at Turin and at Genoa from my friends at Verona which blasted all my hopes of having their company in my journey into Italy. Those who thought it their interest to prevent the journey, tho’ they feigned to approve of it, have found means, in an underhanded way, to prevent it.

I go from hence to Desenzana, where I shall wait ‘till your Ladyship arrives there, or ‘till I can hear from you. If you should have changed your plan, and should have determined not to visit Desenzana, or Verona in your way to Florence pray write me by the next post, which will leave Milan on Wednesday next in the afternoon. Direct to me à l’Auberge della Posta Vecchia à Desenzana. – where, if you come, you will be so good as to join me. If you should not come, I shall proceed by Mantua to Florence as soon as I get your letter, which will be on Thursday next. I shall hope at least to have the pleasure of meeting you at Florence.

I know you will rejoice with me when I inform you that upon my arrival at Milan I found very agreeable letters, both from America and from Bavaria. I had one charming one from Munich in answer to one of mine of the 17th. of August.

I will tell you nothing of my journey to Turin and to Genoa ‘till I see you. – Only this I will tell you, that Lord HoodFootnote190 thinks himself perfectly safe at Toulon, - and that an English squadron is expected at Genoa, to keep the Genoese in order.Footnote191

Adieu, my dear and most amiable Lady Palmerston. Make my best Compliments to Miss Carter and to Lord P.Footnote192 and believe me ever your Ladyships

Most devoted Humble Servant

Letter 2: 29 and 30 November 1793

Pisa Friday 29th. Novr. | 1793

If ever there was a spoilt child I am one, and it is all your fault. I have been so long used to your agreeable company that I really feel quite aukward [sic] when I am deprived of it; and going from you is so like going from home that it makes me feel quite lonesome and melancholy. It fills my mind with sentiments to which, alas! it has long been unaccustomed. What a train of reflexion does that word home call up, and what inexpressible sentiments does it excite in the mind of a person like me, an exile doomed to roam in the wide world, without a home, and without a friend? – But this is not the subject upon which, upon setting down to write to you, I meant to entertain you; nor is it ground upon which I dare trust myself.

My journey from Florence to this place was performed without the least accident; but on the other hand without either instruction or amusement. – Neither Pistoria nor Lucca afford any thing worthy of attention, nor do I think the Country about them at all beautifull. The Country about the Baths of Lucca is very pritty, but it is by no means to be compared to Switzerland. I arrived here, from Lucca, yesterday, about noon and meant to have left it tomorrow morning, but the Marquis ManfridiniFootnote193 having persuaded me that it would be right to pay my respects [to] their Royal Highnesses I shall stay tomorrow in order to be presented to the Grand DukeFootnote194 in the Evening, and shall set off for Leghorne early on Sunday morning.

You will doubtless have heard of the burning of the French Ship of War at Leghorne, and will expect that I should give you some particulars of that melancholy event. All accounts agree in this, that she must have been set on fire by design, and nobody doubts of what description, or party, the Person or Persons are who committed the most horrible crime, - but who they were has not yet been discovered. Several of the ships Company who were saved are in confinement upon suspicion. About 400 Persons were saved and about 200 destroyed in the flames; they were mostly however, if not all French. Dont be shocked at this however, I beg of you.Footnote195 There are flying reports of an action under the walls of Toulon, in which the English are said to have given the French a sound drubbing. I wish these accounts may be true with all my heart, but as no ship is arrived from Toulon, and as nobody can tell how the accounts came I own I doubt their authenticity. As I dont mean to close my letter till tomorrow Evening if I should pick up any news at Court I will inform you of it. – And with this I shall wish your Ladyship a very good night.

Saturday Evening 10 O’Clock Here I am, and still wind-bound. I am this moment returned from Court, and instead of setting off tomorrow morning for Leghorn, as I intended, I find myself obliged to stay here another day, having received an invitation to dine at Court tomorrow; which invitation, I was told, I could not with decency refuse. You would doubtless think it nothing but affectation, tho’ I were to confirm it with an oath, that the Court air has already given me the vapours. It is however but too true.

Their Royal Highnesses were remarkably gracious to me. You will judge whether those about them followed their example. I found among the Company two old acquaintances, the Prince and Princess RospigliosoFootnote196 who were formerly at Munich where the[y] spent several weeks. To meet an old acquaintance in a strange place is doubly agreeable.

The news at Court did not amount to much; - Fort Luis they said was taken, - but that the news papers said three days ago.Footnote197 The number of people lost in the French ship that was burnt they now say amounts to only about 80. I am very glad it is no more, however. I am very sorry to find that Admiral CosbyFootnote198 has either left Leghorn this afternoon, or that he will certainly leave it tomorrow. No news from Toulon. A very clever miss something whose acquaintance I have made here, but whose name I have forgot (she is waiting here for Lady Herries’sFootnote199 arrival,) – told me that Lord HerveyFootnote200 was to leave Toulon the 16th. of this month to return to Florence.

By the Bye I must tell you I have made an acquaintance with Lady Bolingbroke.Footnote201 I met her first at a Mrs. StarkesFootnote202 where Govr. EllisFootnote203 carried me, and I then visited her at her own lodging. I found her with her Father,Footnote204 a Lady I did not know, and three charming children.Footnote205 Poor thing, how interesting she is in her present unfortunate situation! I felt quite grieved for her. Luckily I leave Pisa soon, or I do not know what I might have been tempted to do to cheat away her tedious lingering hours.