ABSTRACT

This paper examines the rise and fall of the British popular microscopy movement during the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century. It highlights that what is currently understood as microscopy was actually two inter-related but distinct communities and argues that the recognized collapse of microscopical societies in the closing decades of the nineteenth century was the result of amateur specialization. It finds the roots of popular microscopy in the Working Men’s College movement and highlights how microscopy adopted its Christian Socialist pedagogy of equality and fraternity, resulting in a radical scientific movement that both prized and encouraged publication by its amateur adherents, who often occupied the middle and working classes. It studies the taxonomic boundaries of this popular microscopy, particularly focusing on its relationship with the study of cryptogams or ‘lower plants’. It explores how its success combined with its radical approach to publication and self-sufficiency created the conditions for its collapse, as devotees established a range of successor communities that had tighter taxonomic bounds. Finally, it shows how the philosophy and practices of popular microscopy continued in these successor communities, focusing on the British expression of mycology, the study of fungi.

1. Introduction

The study of the natural world in Great Britain underwent considerable and rapid change at the end of the nineteenth century as new ‘disciplines’ emerged, territories shifted, and the research landscape expanded.Footnote1 Within these seismic shifts, historians have described a trend towards experimental research and professional researchers, as several new methodological disciplines emerged and established themselves, such as genetics, biochemistry, and microbiology, and other disciplines underwent substantial restructuring, such as the laboratory-focused ‘New Botany’ imported from Germany.Footnote2 These changes sought to wrest the study of the natural world from the amateur dilettante and the devoteeFootnote3 naturalist and instead reform it as a middle-class profession, codified into academic institutions and professional societies, to which the amateur masses would act as a ‘an efficient, regimented, fact-gathering force’,Footnote4 or to quote a contemporary observer a ‘field army’, who by numbers alone would provide data for the professional researcher to work with.Footnote5

Whilst the closing decades saw the rise of numerous disciplines, they also saw, conversely, microscopy (as distinct from the use of the microscope) undergoing an observable collapse, as local and national microscopical societies folded and those remaining lost much of the prestige they had previously held.Footnote6 Historians of science have previously argued this to be due to the microscope becoming ‘a tool of professionalization, which in turn sent the instrument into the separate domains of zoology, anatomy, entomology, and so on’.Footnote7 However, this argument ignores the distinct nature of popular microscopy as practiced in the nineteenth century, by those who would today be identified as amateurs, and the impact of the emerging taxonomic disciplines dedicated to the study of neglected taxa, such as fungi, bryophytes, and ferns, on its eventual fall from grace.

Here though, the term discipline is perhaps used erroneously for, whilst popular microscopy in late-nineteenth century Britain more than meets the majority of criteria to be considered a scientific discipline through self-propagating its study, training recruits, and maintaining journals dedicated to the subject, it lacked the professional institutional support that many definitions assume.Footnote8 Nor is it a term implied by any of its chief proponents, who instead go through rather complicated linguistic hoops to avoid giving any definition to popular microscopy. Indeed, the closest term adopted is hobby. In his first editorial for Science Gossip, Mordecai Cubitt Cooke suggests readers who ‘desire a scientific hobby’ should ‘above all’ purchase a microscope. He defines a hobby as ‘some study or pursuit by which is of [a persons] own free selection, and to which he votes himself in his moments of leisure’,Footnote9 and it is this concept of microscopy, accessible to all and removed from practicality, that was carried throughout the second half of the century. Cooke was a prominent Victorian mycologist and science popularizer, as well as a central figure in the popular microscopy movement. As such, I shall continue to use the term hobby when referring to microscopy, in the sense of the word defined by Cooke and separate from derogatory associations, or occasionally the terms community or movement when talking about popular microscopy in a wider social context or in reference to its wider pedagogical goals respectively.

In this paper popular microscopy is put forward as a distinct movement, rooted in radical Christian pedagogy, separate from the academic and methodological discipline currently understood as microscopy. It is situated as a natural history focused extension of the movement for the liberal education of working men characterized by the Working Men’s College and its development is traced from this organization to the pinnacle of its institutional expression in the guise of the Quekett Microscopical Club, an explicitly amateur London-based organization that became a central hub for the teaching and research of microscopy in the second half of the nineteenth century. Microscopy’s subsequent fall from grace is then explored in the framework of emerging cryptogamic specializations, such as mycology (the study of fungi), with particular focused placed on the Yorkshire mycologists. In this context, its history is revisited and recontextualised, with the narrative focuses on central actors in both popular microscopy and the minority taxa disciplines.Footnote10 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, who was a pivotal figure in both microscopy and mycology plays a central role in this account.

By placing the history of microscopy within the wider history of radical working-class education, the paper argues the collapse of microscopy can best be understood in terms of amateur differentiation rather than professional division. It argues that, as microscopy increasingly lost its pedagogical function, it was the abandonment of the hobby by amateurs in favour of more taxonomically-strict study (such as mycology) that facilitated the downfall of microscopy and that the professional adoption of the microscope into distinct disciplines occurred afterwards. Finally, the paper moves past the nineteenth century and explores the beginnings of new minority taxa disciplines, exemplified through mycology, arguing that the represent a direct continuation of the educational project of popular microscopy.

2. The development of microscopy in nature study

The modern history of the microscope, and the birth of microscopy as a discipline, arguably begins with the invention of the achromatic objective by Joseph Jackson Lister in 1830.Footnote11 Before 1830, the microscope had largely been restricted as a tool of philosophers, more important for its metaphysical consequences than its contributions to natural history. Whilst mechanical and optical improvements had continuously been achieved on the microscope, their effects were so slight as the microscope at the end of the eighteenth century was only marginally better than one at the beginning.Footnote12 A principal reason for this lack of improvement in the microscope, and its lack of application in natural history was the substantial distortion caused to images by the use of successive lenses (as used in confocal microscopes), limiting both resolution and magnification. Thus, whilst microscopic life could be observed it was unable to be accurately measured and reliably quantified.

The achromatic objective, however, substantially reduced these distortions and in doing so allowed microscopy to be fully embraced within natural history and the confocal microscope to become the dominant instrument of the Victorian laboratory. Indeed such was the impact of the achromatic objective that ‘it drove scholars to change their representations of the instrument, of the scholars themselves and of the emerging discipline … ’.Footnote13 It also had a substantial effect on the architecture of the emerging discipline, with the Microscopical Society of London (later the Royal Microscopical Society) being formed in 1839, with the aim of ‘the promotion of microscopical investigation, and for the introduction and improvement of the microscope as a scientific instrument’.Footnote14 It had a particular focus on standardization of the microscope and saw, amongst other things, the introduction of the standard 3 × 1 inch slide.Footnote15

Whilst some resistance initially existed to the confocal microscope, by 1840 its usefulness had become widely accepted and instead interest turned towards applications for microscopy.Footnote16 In a research landscape dominated by observation and classification, substantial application was quickly found in natural history, with the microscope enabling taxonomists access to numerous new characteristics and unfurling new species cryptic at the microscopic level. The major benefactors of this development were those interested in the minority taxa, which include insects, protozoa, and on the botanical side the cryptogams, or lower plants, a taxonomic classification covering the fungi, bryophytes, algae and ferns.

With the major observational flaws now fixed, the microscope became a powerful tool with its research potential quickly realized. As such, it became imperative for many in the British research community that the microscope become widely available and accessible. This was particularly true for Britain; whose culture of amateur nature study was particularly strong in comparison to the continent. William B. Carpenter (1813–1885), a Fellow of the Royal Society, professional academic, and Unitarian, suggested the Society of Arts to offer a prize for two types of instrument: a school microscope for less than 10s 6d and a student’s microscope for less than 3 guineas. This was advertised in February 1855and awarded later that year to Field and Co. of Birmingham.Footnote17 This marked the beginning of the manufacture of a class of affordable microscopes that was to propel microscopy toward being a dominant and accessible scientific discipline.Footnote18

As a further result of its accessibility, the microscope became a fashionable item and became a source of ‘healthful recreation’ not only within Great Britain but across the western world.Footnote19 However, within Great Britain at least, those of the lower-middle classes interested in microscopy beyond its entertainment value lacked sufficient support to both build their skills and publish their research. This need was soon met by the Quekett Microscopical Club, to be discussed further later, and a rising number of regional microscopical societies, combined with increased provision of a number of popular microscopy text books.

3. Microscopy as an educational project

This, then, shows the origins of microscopy within the framework it is traditionally understood: of social and institutional development mirroring developments in the instrument. However, in exploring the origins of popular microscopy a different history must be put forward, a history of working men’s education. As has been well documented, various political and societal developments had impressed upon the middle classes the need for working men to be better educated.Footnote20 However, there was substantial disagreement as to the form and purpose of this education. Early attempts, such as the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and the Mechanic’s Institutes, focused primarily on the provision of facts and on technical instruction, and fearing the over-education of workers, excluded politics, fiction and theology. Notably, the legacy of these institutions was failure; the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge had collapsed by 1846, whereas the Mechanical Institutes, chronically underattended, had largely stopped functioning by 1851.Footnote21

The Working Men’s College (WMC), which was opened by Christian Socialists in direct response to the Chartist Movement, differed strongly from previous attempts. Though still paternalistic, its middle-class founders seeking to ‘cast the working men in their own image’,Footnote22 through the provision of a ‘liberal education’ that had previously been restricted only to the elites. Based on neither conservative reactionism nor militant working-class secularism, the Christian Socialists sought a third way based on Christianizing the socialist principle of cooperation.Footnote23 Importantly, teachers and students shared informal activities, such as choirs and natural history excursions, in an effort to break down further social barriers.

Heavily focused on the humanities, and with a political core, the college nevertheless embraced the sciences. It did so from a substantially different philosophical viewpoint than other contemporary adult education initiatives aimed at the operative classes, which increasingly moved towards the vocational and technical instruction of workers.Footnote24 As summarized in 1861 by Litchfield, a founding member of the WMC, the educational philosophy of the institution was as such: ‘that the end of all human existence is not to make so many shillings a week’.Footnote25

The history of the WMC was linked to that of British mycology through the work of Mordecai Cubitt Cooke. Cooke's association with the college is largely unrecognized by historians of education, perhaps due to his brother’s more intimate involvement. Chiefly remembered today for his mycological contributions, M.C. Cooke spent much of his early career as a radical educator, involved in both adult and children’s education. Born into a dissident church (Calvinist Baptist) family, he was an early adopter of Pestalozzian pedagogy and a staunch advocate for science in the classroom.Footnote26 He was present at the inauguration of the college in 1854, having been the bookkeeper for a founding association, namely the Working Tailors’ Association, and was accompanied by his brother Ebenezer Cooke, who would become a core member of the college’s faculty. More importantly, he was later employed by the college in 1861 to teach an evening class of Physiological Botany. In introducing the class, it is notable that Cooke emphasized the use of the microscope in his teaching plan, reflecting an approach to botanical teaching in line with the novel teaching systems being pushed by Thomas Huxley and his contemporaries.Footnote27

Whilst projected to teach forty lessons for the WMC, Cooke left before completing the classes for unknown reasons. However, he remained in contact with his pupils, including Alfred Grugeon (1826–1913), and remained known to the college, being invited to become the Curator of its Museum in 1875. Regarding his ex-pupils, he continued to meet with them socially. During one of these meetings in 1862, he and his former students agreed to form a Society of Amateur Botanists whose objectives would be to render:

mutual assistance in the study of British Plants, by organised Excursions into the Country-the interchange of specimens-the communication of papers the establishment of a Library, herbarium, and Museum, or such other means as may from time to time be deemed expedientFootnote28

In 1865, when Cooke founded the Quekett Microscopical Club, the details of which I now turn to, the Society of Amateur Botanists was viewed as the blueprint. Thus, the Quekett Microscopical Club can be traced directly to the Working Men’s College and the ideals of equality and fraternity that it espoused.

4. Microscopy and periodicals: a practice of publication

If the blueprint for popular microscopy lay in the Society of Amateur Botanists, its realization and success occurred through its close association with a number of scientific publications that allowed it to reach a wider audience. This emergence of popular microscopy as a hobby coincided with a boom in the production and variety of scientific periodicals, as, globally, the number of scientific periodicals increased from approximately 1000 in 1850–10,000 by the end of the century.Footnote29 Many of these were commercial journals, unattached to specific societies and which published, in the view of Charles Darwin, ‘discussions & observations on what the world would call trifling points in Natural History’.Footnote30 These commercial publications had a strong bias towards natural history and, particularly with Great Britain, a trend towards active amateur engagement.Footnote31

Notable amongst these commercial journals was Hardwicke’s Science Gossip, which had a particularly strong focus on microscopy.Footnote32 Launched in 1865 and originating from the meetings of the Society of Amateur Botanists, it was a collaboration between the natural history publisher Robert Hardwicke (1822–1875) and Cooke, who served as the journal’s initial editor.Footnote33 It was Cooke’s editorship of the journal that shaped its content and philosophy, with Cooke facilitating another community in which amateur researchers could, metaphorically, congregate. Indeed, the very naming of the journal highlights its central placement within the campaign for liberal education. Initially, Cooke sought to the name the journal The Veil of Isis, a name immersed in the classics deemed so essential to the working man’s education by the WMC, though this was vetoed by Hardwicke in favour of ‘a name everyone could understand’.Footnote34

However, the new name, also communicated the journals ideals and, despite initial misgivings, Cooke soon adopted the name as a battle standard. Writing in the editorial for the second volume, Cooke wrote:

we again announce our name, however undignified it may be, and with it gain admission to the firesides of thousands, whilst the same talisman excludes us, we hope, from the drawing-rooms of only a fewFootnote35

… gossip with our readers, as a man chats to his friend, of passing events in which we are interested, to ask and answer queries, and pass a pleasant half-hour in talking of scientific subjects in the language of the fireside, and not as savans.

Science Gossip quickly became a central hub of a new, holistic, microscopy and regularly featured articles on cryptogamic botany as well as other explorations of microscopic and marginalized taxa. Indeed, such was its ties to the emerging community that the journal hosted the following advert:

It appears to me that some association amongst the amateur microscopists of London is desirable, which shall afford greater facilities for the communication of ideas and the resolution of difficulties that the present Society affords, and which, whilst in no respect hostile to the latter, shall give amateurs the opportunity of assisting each other as members of an amateur-society, with less pretentious, holding monthly meetings in some central locality, at an annual charge sufficient to cover the incidental expenses—say five shillings a year— on the plan of the Society of Amateur Botanists. By the publication of this letter the general feeling of the parties interested will be ascertained, and by this further action determined.Footnote36

5. Communities and organisation of microscopy

Soon after its founding, the QMC became one of two main societies for the study of microscopy in Britain, with the other being older and better established Microscopical Society of London in 1839. The two societies arguably leaned to different understandings of microscopy: the RMS, with its steeper entry fee, tended towards a more professional and methodological microscopy. Meanwhile the QMC, appealing to a broader social demographic, tended towards a more holistic expression of microscopy; it incorporated both field work and biological recording and was accessible to working class practitioners in terms of both learning and contribution. However, increasingly overlap between the two societies in terms of membership ensured both expressions of microscopy found representation in both societies.

The Microscopical Society of London, which received its Royal charter in 1866, was, as reported by Cooke, widely acknowledged as ‘too exclusive, and self-contained’, particularly by the increasing body of amateur plebeian microscopists.Footnote37 In response, the Quekett Microscopical Club sought to capitalize on the increased amateur interest in the microscope and attract a broader, and younger, membership. In this pursuit, it also had a substantially lower membership fee of 10s, half that of the Royal Microscopical Society. As a result, whilst it sported a number of eminent presidents such as Thomas Huxley (1825–1895), in comparison to the RMS the Quekett’s membership originated predominantly from lower-middle classes, though the volume and quality of their research was often substantially higher than that of the RMS.Footnote38

Indeed, it is through Cooke’s involvement in science education, and more specifically the liberal education movement, that the Quekett Club was able to secure such eminent members. Edwin Lankester, the Club’s first President and a strong supporter of the working-class technical education movement, was well-known to Cooke. He had been one of Cooke’s assessors for his Botany exams put forward by the Department of Science and Arts for schoolteachers and later supported Cooke in his post-teaching career.Footnote39 Thomas Huxley was known to Cooke, having been his other assessor. He was also a lecturer at the Working Men’s College, as was Jeremiah Slade, another prominent early member of the QMC. Whilst the QMC has always been understood as an educational organization, its origins highlight the fact that it was a community focused on the liberal education of its adherents. This distinction is important, for whilst many have viewed popular microscopy as seeking to give workers ‘healthful recreation’ and make them good technicians, popular microscopy, or at least a substantial element, sought to make them active researchers, able to critically engage in its study. That it was connected to several accessible avenues for publishing, through its own journal, Science Gossip, and later the cryptogamic journal Grevillea¸ gave practitioners the ability to enter into scientific discourse as equals in a way that lectures and classroom-based teaching did not.

6. More than an instrument: the research practices and philosophy of popular microscopy

From its very foundation the QMC had a taxonomic focus in addition to a unifying instrument, with the first three classes offered by the society focused on microscopic technique, the identification of both fungi, and the identification of mosses.Footnote40 The society also organized regular field work, collecting expeditions, and fungal forays.Footnote41 Indeed, throughout its history the Quekett Club placed emphasis on the potential of microscopy to further knowledge of the minority taxa. The bryologist Robert Braithwaite implored members to focus on the ‘many fields [taxonomic groups] yet but partially explored, to which some of our members may profitably turn attention’, and in doing so listed the mosses, ‘small algae’, and the neglected insect clades of the Thysanura (now the Archaeognatha and the Zygentoma) and the Acaridae as his examples. As such, the members of the Quekett Club can be viewed as a community of taxonomic specialists as much as, if not more so than, specialists with a particular observational tool. Their taxonomic specialism was not of a singular group but rather of a loose collection of minority taxa, abundant in microscopic characteristics essential for identification and ignored or marginalized by well-established disciplines such as botany, zoology, and entomology.Footnote42

Chief amongst these minority taxa were the cryptogams, a former formal classification of ‘non-seed bearing plants’, which contain primarily the algae, bryophytes, ferns, fungi, and fungal-like organisms. In retrospect, the reasons for an amateur microscopical society to cohere around cryptogams are abundant. Macroscopically attractive and diverse, cryptogams contain substantial cryptic speciation only discernible at the microscopic level.Footnote43 From spore shape and size, to specialized cell structures such as cystidia (in the fungi), cryptogams are abundant in microscopic characteristics essential for identification. Unlike in entomology and botany, where magnification is required only at the lowest level, cryptogamic characters are often only discernible at the highest magnifications. Furthermore, most cryptogams were amenable to drying and long-term preservation and, as such, this meant material could be traded freely, allowing comparison and storage with little financial or technical investment. This facilitated engagement with taxa across social strata, enabled the development of a community around the field, and allowed those interested in cryptogams to continue their practice throughout the year. As preservation methods, for example drying or making spirit collections, distort most macroscopic characteristics, such size and colour, this out of season investigation was primarily reliant on microscopes.

Despite previous interest in the cryptogams in the first half of the century,Footnote44 with one notable exception, cryptogamic societies did not exist within Great Britain.Footnote45 Nor did cryptogamists immediately ally themselves with the growing amateur microscopy community. Due to the aforementioned fad of microscopy combined with a lack of training opportunities, the relationship between amateur microscopists and cryptogamists was especially poor during the early days of popular microscopy, the latter not yet absorbed into the former. Miles Joseph Berkeley, widely regarded as the ‘founding father of British mycology’ (Ainsworth, 1987), made his views abundantly clear in his Introduction to Cryptogamic Botany, the foundational textbook of the discipline, writing that ‘ten thousand microscopists of the present day’ were ‘mere trifler[s]’ and, more directly, that ‘[p]erhaps, of all literary dissipation, the desultory observations of the mere microscopist are the most delusive’.Footnote46 His follow up, Outlines of British Fungology, was less dismissive however, and instead noted that for some species ‘so small, and in general so devoid of external beauty “that” it is only the lover of the microscope who is at paints to study them’.Footnote47 This sharp turnaround of opinion represented a quick rehabilitation of the amateur microscopists, and not surprisingly: outside of the fad of the microscope, they were making substantial impact on the knowledge of minority taxa.

Buoyed by increasing civic pride, local and regional microscopic societies had formed across the country during the latter decades of the nineteenth century, providing opportunities for microscopists outside of London to physically meet and exchange ideas. Microscopical societies quickly became homes for cryptogamists and these individuals formed a substantial body of microscopical societies’ membership and leadership, as well as contributing a substantial number of papers to their journals and influencing the societies programme and philosophy. This taxonomic element of microscopy is no more clearly in display than in Cooke’s One Thousand Objects Under the MicroscopeFootnote48 where, of the 490 plant objects provided, over two-thirds (326) fell under the category of cryptogams.Footnote49

There were specialties among cryptogamic researchers, however. Individuals identified, and were identified, as a mycologists, fungologists, bryologists, algologists, etc. However, these identities were both subsumed and interrelated to the identity of the (popular) microscopist, which was viewed as a generalized term that supplemented a more specialist but taxonomically-limited research specification, such as a mycologist or bryologist. For example, in the introduction to British Fresh-Water Algae (1882–1884), Cooke distinguishes between ‘the Microscopists who desire some acquaintances with the organisms met with in their excursions to ponds and ditches’ and ‘absolutely scientific algologists’. Similarly, in Rust, Smut, Mildew, and Mould: An Introduction to Microscopic Fungi, Cooke distinguishes between microscopists and mycologists, referring to both directly throughout the text.Footnote50 Importantly, the identities were not mutually exclusive. Thus when dealing with their taxonomic specialism an individual might refer be referred to by the more specific identity, such as a mycologist, but when stepping into the wider taxonomic sphere of the cryptogams, of which their knowledge was more general, might instead be referred to as a microscopist.

Notably, popular microscopy encompassed more than the microscope. Substantial emphasis was placed on excursions and time spent in the field. In Half-hours with the Microscope: Being a Popular Guide to the Use of the Microscope as a Means of Amusement and Instruction by Edwin Lankester, a Fellow of the Royal Society and the first President of the QMC, four of the six chapters focus on the on the microscope in the context of the outdoors.Footnote51 The book also highlights the emerging taxonomic bounds of microscopy. In the chapter A half-hour with the microscope in the country, Lankester explicitly focuses on ‘the minute forms of mosses, fungi, lichens, and fern’, whereas a further two chapters are dedicated to microscopic marine life such as diatoms, desmids and seaweeds. The final chapter on the outdoors focuses on terrestrial plants ‘in the garden’.

Additionally, in Cooke’s One Thousand Objects for the Microscope with hints on their mounting, extended from his earlier publication, a whole chapter is dedicated to informing would-be microscopists of best practice in the field.Footnote52 In introducing the chapter, entitled Out in the Field¸ Cooke firmly emphasizes the role of field work in microscopy, writing ‘[i]t may be taken for granted that field work must form part of the occupation of the microscopist’. Cooke also puts forward the taxonomic bounds for microscopists writing ‘[n]early all the organised excursions of Natural History and Microscopical Societies are made in search of what is known as “pond life”’, earlier qualifying pond life as ‘smaller fresh-water algae, desmids, diatoms, and such microscopic animal life as the water-fleas and their kindred, the rotifers, the fresh water polyzoa, the almost innumerable infusoria, and larval forms of insect life’.Footnote53

Importantly, however, not all those involved in microscopy were involved in the study of ‘minority taxa’ and journals of microscopy continued to publish articles on relatively-well studied taxa, as well as articles on geology and microscope methodology.Footnote54 As such, microscopy in this period can best be understood as two interrelated activities: the study of objects using the microscope, whose practitioners predominately consisted of professional lab-based biologists and those involved in medicine, but also the study of microscopic life, occupied primarily by a lower-middle class group of amateur devotees. It is in understanding this duality of microscopy that its collapse at the end of the nineteenth century can best be understood.

7. The collapse of microscopy

Despite this prolific growth in microscopical societies across the country, with popular microscopy increasing in popularity and prestige as a movement, by the closing decade of the nineteenth century it was notably in decline. The Manchester Microscopical Society, for example, which was formed relatively late in 1880, was in serious decline by the mid-1890s, with its membership demographic reflecting the increasingly academic nature of microscopy.Footnote55 Similarly, the Royal Microscopical Society had seen its membership drop by over a third from the mid-1880s to 1913.Footnote56 Current scholarship places much of this on the microscope becoming a ‘tool of professionalisation’, and being adopted by already well-established disciplines such as zoology, entomology, and anatomy.Footnote57 However, this explanation ignores a much more pertinent factor: the emergence of amateur networks focused on the study of minority taxa. During the period of decline of microscopy, national societies emerged for the study of fungi (1896), bryophytes (1896), and ferns (1891).Footnote58

Notably, these disciplines emerged not from the metropolitan elite, but rather from an, increasingly provincial, amateur contingent. The British Pterodological Society formed in the Lake District, whereas the British Mycological Society found its origins in Yorkshire.Footnote59 The British Bryophyte Society, formed originally as the Moss Exchange Club, originated from the pages of Science Gossip.Footnote60 This reflected the growing independence of the amateur community, an independence facilitated in part through the educational mission of popular microscopy that encouraged self-reliance and a full engagement in the research process, alongside a growing civic pride movement that transformed provincial towns and cities into scientific centres.

Here the collapse of microscopy is best explored through the rise of mycology. Whilst similar trends are evident in the other emerging taxonomic communities, mycology provides the clearest case study due to the close connection between many of the figures involved. Whilst Cooke held wide ranging interests, writing on subjects as drugs and reptiles, his central interest was fungi and he was a key figure in the foundation of the British Mycological Society.Footnote61 Similarly, George Edward Massee (1845–1917), who would become the first President of the British Mycological Society and later Chairman of the Yorkshire Mycological Committee, was also Cooke’s heir apparent and close confidante. At first in contact through correspondence, Massee soon came to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, as a freelancer where he worked under Cooke’s tutelage and later succeeded him as curator of the cryptogams. At Kew, Massee and Cooke collaborated on Cooke’s famous Illustrations where, such was the level of trust, they engaged in highly controversial artistic practices to the ignorance of all others involved. Massee would also take over from Cooke as editor of Grevillea in 1892 and was active in the world of microscopy, serving as President of the Quekett Microscopical Club from 1900–1903.

The reasons for this close association are intuitive. The identification of fungi was more dependant on microscopy for accurate identification, in comparison to most other cryptogams, and often required a higher magnification and more complex preparation in order to view essential characteristics. For this reason especially, mycology, of all the cryptogamic communities, developed a substantially closer connection, both in terms of personnel and methodology, to popular microscopy.

Mycology, as a distinct field of study, had gradually begun its formation in Britain (and elsewhere) from the final quarter of the nineteenth century. The Woolhope Club began an annual foray amongst the funguses in 1868, providing a yearly venue for the countries’ mycologists to meet. The Yorkshire Mycological Committee, founded in 1891, represented the first permanent mycological organization within the Great Britain and was established to organize and facilitate the Union’s forays.Footnote62 Specialization could also be seen in the development and establishment of publications. Hardwicke’s Science Gossip focused on natural history and microscopy, though it had a leaning towards the cryptogams. From this, Cooke went on to develop Grevillea, a publication explicitly focused solely on cryptogams, that began publication in 1872. This ceased publication in 1894 and Transactions of the British Mycological Society, a publication focused solely on mycology, first published in 1896. Regional publications, such as The Naturalist, also increasingly become centres for the publication of work on minority taxa.

It is notable that Cooke, despite his clear and broad entrepreneurial tendencies, never founded a purely mycological publication or society.Footnote63 It is also notable that these specialist societies emerged in such a short span of each other. Indeed, in acknowledging the role of the emergence of minority taxa disciplines in the collapse of microscopy, the question must be asked as to why they all emerged when they did. For John Ramsbottom, mycologist and historian, the answer was that, by the point of Cooke’s retirement from Kew in 1893, ‘times had changed’ and that mycology had developed such numerous branches that it was impossible for any mycologist, even one with the experience and institutional resources of Massee, to remain ‘the authority’ of mycology.Footnote64 Whilst Ramsbottom had his biases towards Massee that likely clouded his comments, it was true that the amount of knowledge now possessed on fungi had substantially increased during the nineteenth century, as acknowledged by Massee himself who, in giving the first President’s Address of the British Mycological Society wrote that ‘[i]t would not, perhaps, be stating too much to say that the entire amount of knowledge dealing with Fungi as living organisms, that we possess at the present day, has been acquired within [the past sixty years]’.Footnote65 This expansion of knowledge also extended to taxonomy. As reported by Massee’s lieutenant, Charles Crossland (1844–1916), the number of fungi known to Great Britain in 1908 numbered at 5,500, more than double the number known in 1871.Footnote66 Ironically, this development was only possible through the efforts of a generation of microscopists and minority-taxa specialists, who found welcome homes for their research in the pages of Science Gossip, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, and Grevillea. Furthermore, advancement in the scientific knowledge of cryptogams meant that practitioners of both bryology and mycology increasingly turned to ecological studies of their chosen group, further deepening the emerging disciplines and creating further distance from microscopy’s origins.Footnote67

Such was the sum of knowledge contained within mycology alone that it was increasingly impossible for an individual to have command of the entire subject, let alone develop competence in other areas of microscopy, as a taxonomic study. This can be particularly be seen in the production of British fungal flora, or species lists; a relatively common practice for mycological authorities in the nineteenth century, having been attempted by BerkeleyFootnote68 and Cooke.Footnote69 However, Massee’s attempt across four volumes published between 1892 and 1895 remains the last attempt by an individual or small group and was noted as being incomplete.Footnote70 As such, this expansion of knowledge strained the cohesiveness of popular microscopy as a movement as members became increasingly focused on areas of research requiring substantial specialized knowledge to appreciate and considerable time to undertake. This latter factor can particularly be appreciated in the context of field excursions that were the foundation of the Quekett Microscopical Club and taxonomic mycology as a whole. Conducted regularly, the excursions findings were reported in the Journal of the QMC, with a typical number of species being typically reported in the tens for all taxa combined. In contrast, the first fungal foray of the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union in 1888 recorded upward of 300 species during the course of its foray, with over 120 being found in one day.Footnote71

With an increasing inability to communicate across taxonomic lines, the community encompassed by popular microscopy began to split into more specialized successor disciplines, such as mycology, bryology, and pteridology, such that members could maintain the level of shared interest and knowledge necessary for cohesion and to maintain the pedagogical function of the movement.Footnote72 In this, the grounding of popular microscopy in liberal educational ideals likely facilitated amateur differentiation. The discipline mandated self-reliance and heavily encouraged practitioners’ engagement in all aspects of the scientific process: from specimen collection to examination, to eventual publication and long-term storage of specimens. This gave huge independence to practitioners to direct their own learning and pursue their own interests. With such a philosophical framework, the natural drift of practitioners into smaller taxa-focused interest groups and eventual distinct societies would easily be facilitated, particularly in the face of a proliferation of knowledge to master. That this amateur specialization mirrored the professional disciplinisation occurring within the biological sciences highlights that the practitioners of popular microscopy and its descendant specializations saw little difference between themselves and professional researchers.

8. Later developments: provincial mycology as a successor to popular microscopy

Whilst microscopy continued, and continues to this day, the loss of its taxonomic remit was a serious impact to its standing within the sciences and its potential for development. The effect of this loss of definition was accentuated by the fact that the microscope had reached its peak in resolution in the 1880s.Footnote73 As such, the closing decade of the nineteenth century arguably saw microscopy left a methodological discipline with little potential for innovation and at substantial risk stagnation. This loss of innovation had serious implications for its pedagogical function and microscopy, as a movement and as a hobby, quickly became seen as outdated and old fashioned. It subsequently saw a substantial drop in its disciples across the country, as artisan and working-class naturalists attached themselves to new emerging disciplines. Gradually, popular microscopy ceased to be an active research front and amateur microscopy adopted an increasingly vocational pedagogical position, focusing on education and entertainment of the layman but without the pretensions of contributing to the scientific canon.

Indeed, this is particularly evident in how Cooke and Massee differentially address microscopists interested in the microfungi in 1865 and 1913, respectively. For Cooke in 1865, microscopists are variable in their desires, and he provides reason for each group to study fungi:

If variety is desired, here they will have at least 2,000 species for a knowledge of which the microscope is essential. If they thirst for discovery, let them be assured that here also the earnest worker is sure to meet with such a reward. Or if they would acquaint themselves with the manifestations of Divine power as developed in the most minute of created things, let them follow such observers as Tulasne and De Bary, and seek the ‘why and the wherefore’ of the phenomena of mycetal life.Footnote74

As comparatively little is yet known of these bodies, a fair field is open to the enterprising microscopists, with time at his disposal, and a good store of perseverance, to win for himself renown in the discovery of fresh facts, and the elucidation of some of the mysteries which yet enshroud these interesting organisms.Footnote75

Arguably, mycology as espoused by Massee, who had no formal scientific training, and adhered to by the Yorkshire Mycological Committee, inherited the philosophy of popular microscopy. Its adherents were widely practicing scholars, both within natural history and occasionally beyond.Footnote80 Members were focused on the field study of fungi, both taxonomically and ecologically, and combined this with microscopic studies. They also had an interest in working men’s educationFootnote81 and Massee, in his most famous intervention, read advised a young Beatrix Potter and presented her paper to the Linnaean Society, as women were not allowed. Furthermore, working men’s contributions were lionized, both in contemporaries and historic viewpoints. On Charles Crossland’s retrospective of Yorkshire mycology, he emphasizes the contributions of artisan mycologists,Footnote82 and later further emphasizes a history of artisan success in his obituary for Henry Thomas Soppitt.Footnote83

This vision of mycology was not universally held and indeed contrasted with those of other contemporary mycologists. For example, the British Mycological Society had aspirations of a learned society. It published a Transactions and had a Latin motto: Recognosce notum, ignotum inspice. Many of its members were not taxonomists, such as Harry Marshall Ward, Harold Wager, and A.H. R. Buller. Each of these men, all of whom, in the words of one critic, ‘had no eye for species’,Footnote84 held the Presidency of the Society early in its history and their prominence in the society gave it scientific prestige but also a level of exclusivity, as the laboratory was increasingly inaccessible to the amateur.

Indeed, this difference in vision among mycological practitioners would lead to the first intra-disciplinary conflict within mycology, between the fledgling British Mycological Society and the Yorkshire Mycologists led by Massee. Despite their names, the lines were primarily drawn across educational lines. Massee, like Cooke, lacked any formal scientific training as did all other members of the Yorkshire ‘Grand Period’.Footnote85 In contrast, the key figures within the BMS, with the exception of A.A. Pearson were all university educated. Notably, Cooke sided with the YMC.

Other differences are readily apparent. The Yorkshire mycologists were largely all of a similar age, with the majority having been born in the 1840s and 1850s. Furthermore, the vast majority had a research interests across several groups within the cryptogams though all had a noted specialty within mycology, and tended to be general mycologists. In contrast, the dominant figures within the British Mycological Society notably younger (John Ramsbottom b. 1885, A.A. Pearson b. 1874, Elsie Wakefield b. 1886, Carleton Rea b. 1861) and, with the possible exception of Carleton Rea, none would have first-hand experience of the heyday of British microscopy. Furthermore, they were all explicitly focused within the Fungi and often specialized only to specific clades within the group. They British Mycological Society, after the split, was also a much more professional society, with its members more likely to have received a university education.

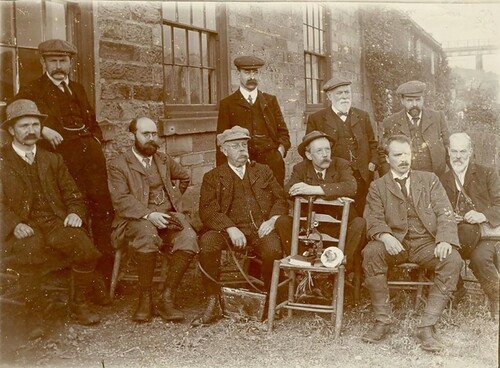

It is telling that throughout the conflict, the Yorkshire mycologists regularly utilized the iconography of the microscope, with this no more in evidence than at the Foray photograph of 1913 where the microscope is given its own seat amongst the attendees (). This utilization of the microscope by Yorkshire mycologists also established the continuity of their mycological practice with popular microscopy. Yorkshire mycologists, as inheritors, were thus able to access the scientific authority previously associated with microscopy and also as maintainers of its pedagogical tradition. In the numerous photos of their Fungal Forays, there is little evidence of social hierarchies and members with vastly different class backgrounds are seen freely fraternizing with each other.

Figure 1. Photograph from a YNU Foray in 1913. Seated behind the microscope is George Massee, and stood behind him is Charles Crossland. To the right of the microscope is Arthur Edward Peck and next to him is William Norwood Cheesman. Reproduced with permission of the Tolson Memorial Museum, Huddersfield.

Whilst the Yorkshire mycologists represent but one succession of popular microscopy, they perhaps have the best claim as a successor community through the close involvement of Cooke and through Massee’s position as Cooke’s understudy and eventual successor. Here, it is evident that Massee and the other Yorkshire mycologists of the ‘Grand Period’Footnote86 represented a continuation of the liberal science pedagogy of popular microscopy, originating from the Working Men’s College, and in this regard represented a different understanding of mycology to that of the BMS – one that would facilitate the conflict between the two mycological communities. This is important for the history of mycology but also for the history of microscopy as, whilst talk of the collapse of microscopy towards the end of the nineteenth century is true in a certain sense, the research practices and philosophies of popular microscopy can continue to be observed in prominent research communities largely unchanged – albeit packaged under a different name.

9. Conclusion

Through tracing the origin of popular microscopy from the radical Working Men’s College, a new understanding of the hobby can be reached. More than a healthful recreation, popular microscopy sought to empower practitioners as researchers in their own right. Similarly, the bitter conflict between the YMC and the BMS during the opening decades of the twentieth century, fought primarily along lines of class and formal education, can be understood as a continuation of the debate focused on the aims and objectives of workers education. Whereas the YMC lionized working-class contributors, the BMS quickly aspired to be a learned society of which exclusion was a defining feature.

Ultimately, many historians have judged the Working Men’s College movement as outdated and reactionary. Even if this is true for some individuals, we must accept that movements are not uniform and contain actors with a variety of distinct motivations and aims. The liberal education pioneered by Cooke, through his variety of journals and clubs, was radical in that it linked self-improvement with publication. This commitment to publication, combined with an emphasis on self-led practical experience, meant that popular microscopy, as pioneered by Cooke, differed substantially from other initiatives to train the working classes which focused on rote learning and whose aim was ‘to inculcate a scientific taste in the population, not to educate future scientists’.Footnote87 Indeed, through publication, microscopy became a means towards equal scientific standing and, through this, a temporary levelling of social standing.Footnote88 This advocation and support for publication through provision of accessible journals with a laissez-fair editorial policy enabled the development of sub-communities that eventually developed into distinct disciplines. Such was the case for popular microscopy which gradually fragmented into the cryptogamic disciplines, many of which announced their presence in the journals of the former.

This is not to say Cooke’s position as a radical science educator are free from criticism. His position as Editor of his publications gave him a position of power and prestige over other microscopists and, whilst supportive of working men’s education, resisted the admittance of women to the Quekett Microscopical Club on two occasions, once in 1868 and the other in 1884 when he sat as President. Indeed, in response to the first attempt he wrote mocking satire of the consequences of admitting women.Footnote89 However, it was largely as a result of Cooke’s endeavours that popular microscopy succeeded where other initiatives to induct working class people into science failed and it is this philosophy that can be seen in mycology’s development in Yorkshire. Whilst anecdotal, it is notable that George Massee read Beatrix Potter’s paper to the Linnaean Society, despite its questionable scientific quality, expanding the educational remit of Cooke. Massee’s support of working-class naturalists can also be seen in Massee’s championing of Henry Thomas Soppitt to an international audience.Footnote90

In assessing popular microscopy in the nineteenth century, a question remains as to its disciplinary status. Through its journals, societies, and emphasis on training, it fits many of the observable characteristics of a scientific discipline. However, as recognized by modern definitions of discipline that require a professional component, disciplines are largely defined through exclusion and discrimination. Practical microscopy, however, from its roots to its ideology, is recognizable by its radical accessibility. As put forward by Cooke the ‘earnest worker’ with a ‘thirst for discovery’ is ‘sure to meet with such a reward’.Footnote91 Those involved in practical microscopy are notably cagey about defining it: the word discipline is rarely if ever used, as are broader terms such as movement. If any word is used, it is ‘hobby’. Certainly, an identity existed, and the majority of authors had no problem addressing their work to the self-defining ‘microscopist’. The history of science is fraught with the fear of presentism and the burden of definition and the case of popular microscopy is no exception. To deny it the status of discipline would be to downplay the seriousness with which its (core) participants undertook their research, yet throughout its history popular microscopy shied away from formalities of classification that might discriminate against the curious and the uninitiated.

And yet discussions of labels largely miss the point. As highlighted, popular microscopy developed into an active research community that managed its own training and publications. Its emphasis on research independence, encouraging practitioners to be engage in the entire research pathway from specimen collection to publication, facilitated the development of new and distinct communities increasingly distant from one another. As has been previously recognized, Victorian England was possessed of a ‘experiential, inductivist “low science” “that” sought to establish their own canons of scientific investigation, criticism, and explanation’.Footnote92 Furthermore, non-professional actors were, in the case of entomology, ‘active in defining their own distinct identities and thereby claiming scientific authority’.Footnote93 Here I have gone further and shown that this low science culture continued throughout the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, and was also capable of establishing and supporting multiple communities, philosophically and materially distinct from their professional counterparts. Particularly, I have focused on microscopy and have shown it to consist in two non-exclusive identities: a (mostly) professional discipline focused on the use of the microscope as an instrument, and a substantially larger popular expression, focused on a broader understanding of microscopic life.

Whilst microscopy as a professional discipline slowly fed into other primarily professional disciplines, as its techniques were gradually accepted and adopted into teaching practices,Footnote94 this had little impact on the predominantly amateur membership of microscopy. These amateur participants not only utilized different techniques and methodologies, but also had a different concept of microscopy that was broadly bounded by a taxonomic concept. As such, the disciplinary collapse of microscopy was not due it becoming a ‘tool of professionalization’ but rather due to the amateur flight from microscopy as they organized themselves into smaller and more specialized research communities focused on specific taxa. This caused microscopy to lose its broad taxonomic remit alongside its reputation as a field of discovery. Importantly, the abandonment of microscopy represents not a change in methodology, as those who left to focus on local field clubs and minority taxa societies continued to engage in similar activities and avenues of research, but rather an increased desire of amateur practitioners to organize and focus their research in specialist areas. The success of popular microscopy as a movement led to a vastly increasing knowledge base and led adherents to reorganize themselves in order to maintain a community with a shared knowledge pool and similar research aims. Indeed, this rejection of a general microscopy by the amateur majority may have forced the transfer of a profession and instrument-bounded microscopy into other disciplines, who now found smaller audiences for their specialist research.

Rather than collapse, Victorian microscopy underwent a metamorphosis as practitioners continued their hobby in much the same way under a different organizational label. Arguably, popular microscopy served its pedagogical purpose and equipped a wide range of researchers, many of whom were working class, with ability to not only understand science but partake in it. Its collapse then can be seen not as a rejection of its core tenets but rather an enthusiastic embrace of them, as its adherents took upon organization and leadership roles amongst themselves and spread the gospel throughout the provinces – microscopes firmly in hand.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Lynn K. Nyhart, ‘Natural History and the “new” Biology’, in Cultures of Natural History, ed. by Nicholas Jardine, James A. Secord, and E. C. Spary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 426–43.

2 See W. T. Thiselton-Dyer, ‘Plant Biology in the Seventies’, Nature, 115.2897 (1925), 709–12 <https://doi.org/10.1038/115709a0>. for the personal account of William Thiselton-Dyer regarding the ‘New Botany’.

3 For more on the concept of the devotee see Robert H. Kargon, ‘The Emergence of the Devotee: The Changing Face of Amateur Science’, in Science in Victorian Manchester (Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1977), pp. 34–85.

4 Samuel J. M. M. Alberti, ‘Field, Lab and Museum: The Practice and Place of Life Science in Yorkshire, 1870–1904.’ (University of Sheffield, 2001).

5 William D. Roebuck, Salient Features in the History of the Yorkshire Naturalists’ Union. Being the Presidential Address Delivered at Sheffield 29th J Anuary, 1904 (London: Brown, 1904).

6 David Allen, ‘The Biological Societies of London 1870–1914: Their Interrelations and Their Responses to Change’, The Linnean, 4.3 (1988), 23–38.

7 Boris Jardine, ‘Microscopes’, in A Companion to the History of Science (Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016), p. 527.

8 See for example (Kohler, 1982; Stichweh, 1992).

9 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, ‘What’s Your Hobby?’, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip: An Illustrated Medium of Interchange and Gossip for Students and Lovers of Nature, 1.1 (1865), 1–2.

10 For more on minority taxa as a concept see Nathan Edward Charles Smith, ‘Minority Taxa, Marginalised Collections: A Focus on Fungi’, Journal of Natural Science Collections, 7 (2020), 49–58.

11 The work was published in 1830 in a paper entitled ‘On Some Properties in Achromatic Object-Glasses Applicable to the Improvement of the Microscope’ submitted to the Royal Society and published in its Philosophical Transactions Joseph Jackson Lister, ‘XIII. On Some Properties in Achromatic Object-Glasses Applicable to the Improvement of the Microscope’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 120 (1830), 187–200.

12 R. H. Nuttall, ‘The Achromatic Microscope in the History of Nineteenth Century Science’, The Philisophical Journal, 11.2 (1974), 71–88.

13 M. J. Ratcliff, The Quest for the Invisible: Microscopy in the Enlightenment (Farnham & Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2009).

14 S. Bradbury, ‘The Microscope in Victorian Times’, in The Evolution of the Microscope (Pergamon Press, 1967), pp. 200–256.

15 G. L’E. Turner, ‘The Origins of the Royal Microscopical Society’, Journal of Microscopy, 155.3 (1989), 235–48.

16 Bradbury; Jutta Schickore, The Microscope and the Eye: A History of Reflections, 1740–1870 (University of Chicago Press, 2007). For contemporary examples of this sentiment, see article contained within M. J. Schleiden, ‘Ueber Die Wichtigkeit Des Mikroskops in Allen Zweigen Der Naturwissenschaft Teil 1’, Archiv Der Pharmacie, 87 (1844), 68–82.

17 P. La Neve Foster, ‘Special Prizes’, Journal of the Society of Arts, 3.115 (1855), 167; P. La Neve Foster, ‘Premiums Awarded—Session 1854–1855’, Journal of the Society of Arts, 3.137 (1855), 589–90.

18 Olivia Brown, ‘Microscopy and the Amateur’, in The Social History of the Microscope, ed. by Stella Butler, R. H. Nuttall, and Olivia Brown (Cambridge: Whipple Museum of the History of Science, 1986), p. 7.

19 William B. Carpenter, The Microscope and Its Revelations, 5th edn (London: J. & A. Churchill, 1875). For the microscope outside of Great Britain see John Harley Warner, ‘“Exploring the Inner Labyrinths of Creation”: Popular Microscopy in Nineteenth-Century America’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, XXXVII.1 (1982), 7–33; Brown.

20 For an introduction to this see Thomas Kelly, A History of Adult Education in Great Britain, 3rd edn. (Liverpool University Press, 1992).

21 Colin Russell, Science and Social Change 1700–1900 (The Macmillan Press Limited, 1983).

22 Richard N. Price, ‘The Working Men’s Club Movement and Victorian Social Reform Ideology’, Victorian Studies, 15.2 (1971), 117–47.

23 William S. Peterson, ‘The Working Men’s College Magazine a List of Attributions for Anonymous and Pseudonymous Articles, 1859–1860’, Victorian Periodicals Newsletter, 11.2 (1978), 58–60 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/20085184?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents> [accessed 4 July 2020].

24 Marcella Pellegrino Sutcliffe, ‘The Origins of the “Two Cultures” Debate in the Adult Education Movement: The Case of the Working Men’s College (c.1854–1914)’, History of Education, 43.2 (2014), 141–59.

25 R. B. Litchfield, ‘No Title’, Working Men’s College Magazine, 1861, iii.

26 Paul Elliott and Stephen Daniels, ‘Pestalozzianism, Natural History and Scientific Education in Nineteenth-century England: The Pestalozzian Institution at Worksop, Nottinghamshire’, History of Education, 34.3 (2005), 295–313; Mary P. English, Mordecai Cubitt Cooke: Victorian Naturalist, Mycologist, Teacher & Eccentric (Bristol: Biopress Ltd., 1987).

27 ‘Report of General Meeting’, Working Men’s College Magazine, 3 (1861), 173.

28 Proceedings of the Society of Amateur Botanists, 1863. Manuscript with the Natural History museum.

29 W. H. Brock, ‘Science’, in Victorian Periodicals and Victorian Society, ed. by J. Don Vann and R. T. Van Arsdel (University of Toronto Press, 1994), pp. 81–96.

30 The Correspondence of Charles Darwin, ed. by Frederick Burkhardt and others (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

31 Ruth Barton, ‘Just before Nature: The Purposes of Science and the Purposes of Popularization in Some English Popular Science Journals of the 1860s’, Annals of Science, 55.1 (1998), 1–33; Susan Sheets-Pyenson, ‘Popular Science Periodicals in Paris and London: The Emergence of a Low Scientific Culture, 1820–1875’, Annals of Science, 42.6 (1985), 549–72.

32 For more on the importance of Hardwicke’s Science Gossip, see Dawson, Lintott, & Shuttleworth, 2015.

33 Geoffrey Belknap, ‘Illustrating Natural History: Images, Periodicals, and the Making of Nineteenth-Century Scientific Communities’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 51.3 (2018), 395–422. For more on Robert Hardwicke, see English, 1986.

34 Worthington G. Smith, ‘The Late Dr. M. C. Cooke’, The Gardeners’ Chronicle, 56 (1914), pp. 356–357.

35 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, ‘Science-Gossip’, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip: An Illustrated Medium of Interchange and Gossip for Students and Lovers of Nature, 2.1 (1866), 1.

36 W. Gibson, ‘Proposal to London Microscopists’, Hardwicke’s Science-Gossip: An Illustrated Medium of Interchange and Gossip for Students and Lovers of Nature, 1 (1865), 116. Science Gossip also led to the foundation of another less prominent microscopical club named the Postal-Cabinet Club in 1873 (see Brock 1989).

37 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, ‘Early Memories of the Q. M. C.’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 7.45 (1899), 229–38.

38 Allen, ‘The Biological Societies of London 1870–1914: Their Interrelations and Their Responses to Change’.

39 Indeed, the Quekett Club in celebrating Lankester’s tenure as President noted that he was ‘[e]ver foremost in any movement having for its object the advancement of popular science’ Anonymous, ‘Proceedings of Societies: Quekett Microscopical Club’, Journal of Cell Science, 2.6 (1866), 277–80.. For more on Edwin Lankester see English, 1990.

40 ‘Quekett Microscopical Club October 25th 1867’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 1 (1868), 20–21.

41 George Edward Massee, ‘The Q. M. C. Fungus Foray’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 7.44 (1899), 133–37.

42 The importance of microscopy to the taxonomy of minority taxa has previously been explored, albeit in a later period, with a historical study on the role of the electron microscope in reformulating viral taxonomy Ton van Helvoort and Neeraja Sankaran, ‘How Seeing Became Knowing: The Role of the Electron Microscope in Shaping the Modern Definition of Viruses’, Journal of the History of Biology, 52.1 (2019), 125–60.

43 Still further diversity has been identified with the genetic revolution revealing yet more cryptic speciation amongst the fungi.

44 David Allen, The Naturalist in Britain, Second (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994).

45 The Scottish Cryptogamic Society was formed in 1875. Notably, it was originally intended to be the Scottish Mycological Society John Ramsbottom, ‘History of Scottish Mycology’, Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 46.2 (1963), IN1-178.

46 Miles Joseph Berkeley, Introduction to Cryptogamic Botany (London: H. Bailliere, 1857).

47 Miles Joseph Berkeley, Outlines of British Fungology; Containing Characters of Above a Thousand Species of Fungi, and a Complete List of All that have been Described as Natives of the British Isles (London: Lovell Reeve, 1860).

48 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, One Thousand Objects for the Microscope (London and New York: Frederick Warne and Co., 1869).

49 Further examples of the taxonomic bounding of microscopy can be seen in the excursion reports of the QMC, which are largely restricted to the cryptogams and microscopic animal life and in Lois Lane Clarke’s Objects for the Microscope L. Lane Clarke, Objects for the Microscope: Being a Popular Description of the Most Instructive and Beautiful Subjects for Exhibitions, 2nd edn. (London: Groombridge and Sons, 1863).¸ where the majority of subjects suggested from the ‘Vegetable Kingdome’ are cryptogams.

50 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, Rust, Smut, Mildew, & Mould : An Introduction to the Study of Microscopic Fungi (London: Robert Hardwicke, 1865).

51 Edwin Lankester, Half-Hours with the Microscope: Being a Popular Guide to the Use of the Microscope as a Means of Amusement and Instruction (London: Robert Hardwicke, 1859).

52 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, One Thousand Objects for the Microscope with Hints on Their Mounting (London and New York: Frederick Warne and Co., 1900).

53 Whilst mention is also given to the terrestrial cryptogams later on in the chapter, Cooke notably groups these with the flowering plants and highlights these taxa only as of interest to the botanist. However, as will be explored later in the paper, it should be noted that at the point of writing this section, independent societies had already been established for the terrestrial cryptogams (fungi, bryophytes, and ferns) and so the remit of microscopy over these groups was limited.

54 Examples of such publications on well-studied taxa include papers on the Kola bean Hahnemann Epps, ‘On The Kola Bean (Cola Acuminata)’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 3.17 (1866), 1–4. and the nature of pig muscle fibres E. M. Nelson, ‘Striped Muscle Fibre of Pg’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 5.31 (1892), 1–3. Interestingly, Nelson, in introducing the latter paper writes that ‘my opinion is that, if anything is to be done towards the elucidation of minute histological structures, we must attack them as if they were diatoms. There should not be such a thing as one way of examining a histological specimen, and another way of examining the diatom; but there is a right and a wrong way of using the microscope, and the right way is the diatom method, and is the one which should be employed on histological tissue’ (Nelson, 1992: 1). This highlights the central importance of minority taxa in the construct of the concept of microscopy. Examples of geological papers include Heinrich Hensoldt, ‘On Fluid Cavities in Meteorites’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 1.1 (1881), 1–14. and examples of methodological papers include E. M. Nelson, ‘A Simple Method of Finding the Refractive Index of Various Mounting Media’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 5.31 (1892), 8–9; T. Charters White, ‘On the Injection of Specimens for Microscopical Examinations’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 1.1 (1881), 15–19.. However, both geological and methodological papers existed that focused on minority taxa Arthur M. Edwards, ‘The Fossil Diatomaceae Older than Those of Virginia and California, Which Are Older Miocene.’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 6.36 (1895), 1–4; Charles Rousselet, ‘On A Method of Preserving Rotatoria’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 5.32 (1893), 205–9; Charles Rousselet, ‘Second Note on a Method of Preserving Rotatoria’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 6.36 (1895), 5–13; H. Morland, ‘On Mounting “Selected” Diatoms on Slip’, The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 5.31 (1892), 4–7.

55 Brown.

56 Allen, ‘The Biological Societies of London 1870–1914: Their Interrelations and Their Responses to Change’.

57 Jardine.

58 In terms of animal minority taxa, a significant society also formed for the study of molluscs (The Malacological Society of London; 1893), although several entomological societies already existed and whose remit included microscopic animal life.

59 John Ramsbottom, ‘The British Mycological Society’, Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 30 (1948), 1-IN1.

60 ‘The British Bryological Society’, Nature, 153.3895 (1944), 768–768.

61 For examples of Cooke’s wider work see Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, The Seven Sisters of Sleep (London: James Blackwood, 1860) and Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, Our Reptiles and Batrachians: A Plain and Easy Account of the Lizards, Snakes, Newts, Toads, Frogs, and Tortoises Indigenous to Great Britain (London: Allen & Co., 1893).

62 E. M. Blackwell, ‘Fungus Forays in Yorkshire and the History of the Mycological Committee’, The Naturalist, 86.871 (1961), 163–68.

63 English, Mordecai Cubitt Cooke: Victorian Naturalist, Mycologist, Teacher & Eccentric.

64 John Ramsbottom, ‘George Edward Massee. (1850–1917)’, The Journal of Botany, British and Foreign, 55 (1917), 223–27.

65 George Edward Massee, ‘Résumé of the President’s Address’, Transactions of the British Mycological Society, 1 (1896), 15–19. For more on the relationship between Massee and Ramsbottom and Massee see Nathan Edward Charles Smith, ‘Narrative Histories in Mycology and the Legacy of George Edward Massee (1845–1917)’, Archives of Natural History, 47.2 (2020), in press.

66 Charles Crossland, ‘The Study of Fungi in Yorkshire: Part 1’, The Naturalist, 33.392 (1908), 81–96.

67 For examples of early forays into ecology in bryology, see Charles Crossland, ‘The Distribtuion and Association of the Mosses and Hepatics in the Parish of Halifax’, The Halifax Naturalist, 8 (1903), 66–72. For unpublished examples in mycology, see Nathan Edward Charles Smith, ‘Provincial Mycology and the Legacy of Henry Thomas Soppitt (1858–1899)’, Archives of Natural History, 47.2 (2020), 219–35.

68 For Berkeley’s attempts, see Miles Joseph Berkeley, Outlines of British Fungology; Containing Characters of above a Thousand Species of Fungi, and a Complete List of All That Have Been Described as Nativers of the British Isles. (London: Lovell Reeve, 1860); Miles Joseph Berkeley, The English Flora of Sir James Edward Smith Vol. V. Part II. Comprising the Fungi (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, 1836). For Cooke’s attempts see.

69 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, Handbook of British Fungi (London and New York: Macmillan and Co., 1871).

70 Ramsbottom, ‘George Edward Massee. (1850–1917)’.

71 Anonymous, ‘Fungus Foray at Branham and Harewood Parks’, The Naturalist, 13.160 (1888), 321–29.

72 Here successor discipline is used to indicate emerging disciplines that inherited both research remit and practitioners from existing/collapsing research disciplines or communities. In this sense, modern genetics may be viewed as a successor discipline to eugenics or the indistinct ‘plant sciences’ a successor discipline to botany.

73 G. L’E. Turner, ‘Are Scientific Societies Really Neccessary?’, in Essays on the History of the Microscope (Oxford: Senicio Publishing Company Ltd., 1980), pp. 233–45.

74 Cooke, Rust, Smut, Mildew, & Mould : An Introduction to the Study of Microscopic Fungi. pp. 189–190.

75 Ibid., pp. 31–32.

76 George Edward Massee and Ivy Massee, Mildews, Rust And Smuts (London: Dulau and Company, Limited, 1913).

77 Here some level of discretion should be paid to accounts about Massee. The American Mycologist, whilst visiting Massee, wrote that Massee thought ‘microscopic characters of little or no value in such plants, and·that one is just as safe in relying on gross characters as upon microscopic characters’. This is somewhat true for the genus Amanita, the group under discussion, but it should also be noted that Massee was a noted teller of untruths Nathan Edward Charles Smith, ‘A Figure in the Fog: George Edward Massee’, The Naturalist, 145.1103 (2020), 8–12. who, by Atkinson’s own admission liked to ‘stir up the hornets nest’ in people. With such knowledge, Atkinson’s report on Massee’s views on the microscope are also likely to be attempts by Massee to wind up or troll Atkinson.

78 George Edward Massee, ‘Mycology, New and Old’, The Naturalist, 37.371 (1912), 366–67.

79 Charles Crossland, ‘Mycological Meeting at Sandsend’, The Naturalist, 38 (1913), 21–28.

80 Charles Crossland, for example, maintained an active research interest in local history and linguistics.

81 An example of this is Soppitt providing botany lessons to the Bradford Technical College.

82 Crossland, ‘The Study of Fungi in Yorkshire: Part 1’; Charles Crossland, ‘The Study of Fungi in Yorkshire: Part 2’, The Naturalist, 33.393 (1908), 147–56.

83 Charles Crossland, ‘Henry Thomas Soppitt’, The Halifax Naturalist, 4.20 (1899), 31–36.

84 Ramsbottom, ‘The British Mycological Society’.

85 E.M. Blackwell, ‘Links with Past Yorkshire Mycologists’, The Naturalist, 86.877 (1961), 163–68.

86 Blackwell, ‘Links with Past Yorkshire Mycologists’.

87 Richard A. Jarrell, ‘Visionary or Bureaucrat? T. H. Huxley, the Science and Art Department and Science Teaching for the Working Class’, Annals of Science, 55.3 (1998), 219–40.

88 This can be observed in the Chester Society for Natural Science, founded by the Christian Socialist Charles Kingsley, where on outings all members, regardless of class status, travelled second class on the railway. Similarly, when the American mycologist visited Massee and the Yorkshire mycologists he noted they all travelled third class and all mycologists, regardless of class, slept two to a room during the foray.

89 Mordecai Cubitt Cooke, Songs Written for the Excursionists’ Annual Dinners, Q.M.C. (London: Keating, 1878).

90 Smith, ‘Provincial Mycology and the Legacy of Henry Thomas Soppitt (1858–1899)’.

91 Cooke, Rust, Smut, Mildew, & Mould : An Introduction to the Study of Microscopic Fungi.

92 Sheets-Pyenson, p. 551.

93 Matthew Wale, ‘Editing Entomology: Natural-History Periodicals and the Shaping of Scientific Communities in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 52.3 (2019), 405–23.

94 Graeme Gooday, ‘“Nature” in the Laboratory: Domestication and Discipline with the Microscope in Victorian Life Science’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 24.3 (1991), 307–41.