?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper examines whether the prosociality of village leaders who were involved in the original implementation of a resettlement decision impact the well-being of households from seven villages four years after the displacement. In particular, we report the significant statistical correlation between the level of group cooperation of village officials as elicited from a public good game in seven rural villages and the reported levels of life satisfaction four years after the resettlement. The data comes from two sources: (i) a laboratory experiment with village officials at the time of resettlement, and (ii) follow-up telephone interviews with resettled villagers. We find that these prosocial attitudes of leaders complement other sustainable livelihood measures in promoting the well-being of resettled villagers.

I. Introduction

Voluntary or involuntary resettlement favoring urban or industrial development over the displacement of local rural communities place millions at risk every year all over the industrializing world (Cernea Citation2006). While not all resettlement is involuntary or unwelcomed, ostensibly because rural households affected may be enriched by the anticipated land and farmland compensation, there is considerable evidence showing that resettled households face considerable challenges in restoring sustainable livelihoods. This problem is further exacerbated if the resettlement was unanticipated, unwelcomed, and lowly compensated (Billig Citation2016; Tuval-Mashiach and Dekel Citation2012; Pham, Van Westen, and Zoomers Citation2013). Hence, there is an increasing need for researchers to understand how best to mitigate different risks and promote sustainable livelihood outcomes for displaced villagers (Cernea Citation1997, Citation2000; Scudder Citation2012). While there are ample studies which focus on best practices in the implementation of resettlement projects which center on improving infrastructure (Reddy, Smyth, and Steyn Citation2017; Gentry Citation1997; Webber and McDonald Citation2004), retraining (Bazzi et al. Citation2016; Cernea Citation1997; Dawley Citation2007) and increasing the resources made available to the resettled villagers (Cernea Citation1988, Citation2008; Kinsey and Binswanger Citation1993), our paper focuses primarily on the importance of the heterogeneous preferences of the implementers in this context. In particular, we examine the effect of the prosociality of Chinese village officials during the resettlement implementation on the well-being of the villagers four years after the resettlement had taken place. This study therefore complements Huang et al. (Citation2021) which found that the prosociality of the selfsame Chinese village officials also predicted the difference in the level of support for the resettlement programme during its implementation phase.

We consider the behavioral implications involving the social preferences of village leaders involved in the implementation of the resettlement and the well-being of households years after the displacement taking into account other sustainable development goals as control variables. In particular, we examine the role of group cooperation of village officials in seven rural villages and the well-being of villagers four years after resettlement while controlling for the villagers’ eventual financial, economic, and social status. The data comes from two sources: (i) a laboratory experiment with village officials at the time of resettlement, and (ii) follow-up telephone interviews with resettled villagers four years later. Our data is unique and valuable in that, first, it covers seven of the eight villages involved – both the villagers and village leaders. We find that villages whose officials had exhibited greater group cooperation in the laboratory were more likely to report higher life satisfaction than villages whose leaders contributed low amounts. We find that these prosocial attitudes of leaders complement other sustainable livelihood measures in promoting the well-being of resettled villagers. This study corroborates the relevance of laboratory measures of prosociality to subjects’ achieved levels of sustainable livelihoods in the field.

Why should implementer effects be important in the context of rural resettlement? In China, rural land requisition requires a change of land ownership from a status of ‘village collective-owned’ to ‘state-owned’, a process during which the municipal government must closely work with the elected village officials of affected villages. As a double agent in this process, village leaders are both acting on behalf of the community they had been elected to serve as well as the spokes-people representing the decisions of the government to their constituents. The prosociality of these leaders may determine whether they carry out their duties in a clinical fashion and promote the agenda of the government without adequately considering the welfare of the community that is being displaced; or whether they present the concerns of the community to the authorities and try to find ways of redress (Tendler and Freedheim Citation1994). It is apparent that these two leadership styles lead to different outcomes, whereby the latter will lead to delays and cost increases on the part of the government, but may benefit the community in the longer term.

The issue of such implementer effects have long been questioned in the literature. For example, Nobel prize winners Banerjee and Duflo (Citation2009) questioned whether estimated treatment effects of studies might not be a consequence of the unique characteristics of the implementer especially when the implementing agency is small. Our paper is closely aligned to another study considering implementer effects. Wakano, Yamada, and Shimamoto (Citation2017) found that the heterogeneous preferences of project implementers played a considerable role in natural field settings. Their study measured the altruistic preferences of project staff who were involved in the training programmes in post-harvest technology projects. They found that their giving in the dictator game predicted the participation rate and number of actual participants in the training sessions of beneficiaries.

However unlike external agencies giving aid to villages where the implementers are outsiders, in the context of rural resettlement, the implementers are insiders. Hence our contribution adds to the literature on how the prosociality of leaders affect the groups who follow such leaders (see Kosfeld and Rustagi Citation2015). This is part of a growing literature showing how certain characteristics of local leaders can affect the success rate in the implementation of public projects.Footnote1 Social preferences of community leaders and their impact is an important but neglected factor in this literature.

We also contribute to the literature on the relevance of social preferences as measured in the laboratory to real economic decisions in the field, such as establishing and sustaining behavioral norms in society, increasing productivity in the marketplace, reducing natural resource depletion, and influencing market outcomes and in this case, promoting the long run interests of the community. Along this line, a growing body of studies have been conducted which have established the link between social preferences elicited from the laboratory to actual decisions made in the field (Barr, Lindelow, and Serneels Citation2004; Bouma, Bulte, and van Soest Citation2008; Carter and Castillo et al. Citation2002; Carpenter and Seki Citation2011; Cardenas and Carpenter Citation2005; Fehr and Leibbrandt Citation2011; Karlan Citation2005; Leibbrandt Citation2012; see Cardenas and Carpenter Citation2008 for a survey of field study conducted in the developing world). The use of laboratory elicited measures of cooperative behaviors therefore offers policymakers and academicians the flexibility of incorporating revealed preference methodology in their economic toolkit. While these existing literature on the relevance of laboratory preference measures links between decisions made in real life by the same subjects, considering the prosociality of those implementing important projects and the well-being of those whom they interact with is a relatively new field of research, this study on the other hand, aims to connect ones’ behavior in the lab with their work outcome in the field, measured by the responses of other related agents. By doing so, we extend the applicable scope of other-regarding preferences to its impact on other-related agents and demonstrate the value of using lab-in-the-field experiments for the understanding of behaviors in the field.

Our work complements previous strands of literature examining the prosociality of leaders outside of a laboratory setting, using stated preference methods such as self reports of social value orientation (Balliet, Parks, and Joireman Citation2009; McClintock and Allison Citation1989; Mischkowski and Glöckner Citation2016; Pletzer et al. Citation2018) and self-reports of Big Five personality traits (Kagel and McGee Citation2014; Proto and Rustichini Citation2014; Volk, Thöni, and Ruigrok Citation2012). The results of these papers provide ample evidence of the link between self-reports of prosocial preferences and cooperative behaviors in the field.

We argue that understanding the prosociality of leaders is important in the area of public policy implementation on the ground. We hypothesize that the group cooperation of the leadership team in each village has a positive impact on the future well-being of their constituencies through three possible channels. First, a more prosocial leadership team might be willing to expend more effort in ensuring that the conditions of the resettlement were adequate and beneficial before arranging for villagers to sign over their homes. Second, a more prosocial village leadership team might act on behalf of the villagers in resolving contract violations either by third-party contractors or by the stakeholders themselves, in order to ensure more equitable outcomes for villagers. And last, a more prosocial leadership team might better prepare their constituents to face the relocation costs associated with the resettlement thereby ensuring a smoother transition from villager-farmer to urban dweller. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis in our paper: villages whose officials contribute more in the public account in the standard public goods game, have a higher percentage of villagers who are more satisfied with their life situation four years after the resettlement decision. We examine this hypothesis accounting for changes to their human, financial, physical economic infrastructure, and socio-political assets under a sustainable livelihood framework. Our results provide confirmatory evidence of this hypothesis. Using a multinomial logit, we find that households from the villages where the officials showed higher levels of cooperation report a statistically significant higher satisfaction level. Along with this result, we also find that higher assets correlate positively with higher reported life satifaction while lower savings are negatively correlated with satisfaction. For every 1 yuan increase in PGG contributions made by the village leadership team, the odds increase by a factor of 1.124–1.134 of reporting ‘no change’ compared to being ‘worse off’ than before the resettlement, and had a factor of 1.201–1.231 higher odds of reporting ‘better off’ compared to being ‘worse off’. Hence this study calls for an increased emphasis on the selection of leaders, especially in considering the prosocial characteristics of the leadership team.

It is important to note that this link between the prosocial preferences of grassroot leaders and higher life satisfaction outcomes four years after the resettlement decision may not translate in other domains involving monetary exchanges. For instance, employer-employee transactions in the workplace. It is possible that employees might exploit employers who are other-regarding in order to increase their own payoffs. The literature on motivation crowding out has shown that in such market transactions, social norms of self-interest and selfish behaviors may dominate altruistic ones (Ellingsen and Johannesson Citation2008; Irlenbusch and Sliwka Citation2005; Bowles and Polania-Reyes Citation2012). Ben-Ner (Citation2013) does provide a theoretical framework which describes how efficiency wages and incentive compatible contracts lower overall social welfare if employers and employees possess other regarding preferences.

This paper proceeds as follows: Section II briefly introduces the background of the resettlement project and the issue of sustainable livelihood from the perspective of land-lost farmers. Section III presents the methodology, including the experimental games for village officials and the telephone survey for villagers in the field. Section IV analyzes the results, Section V explains the broad implications from our study and Section VI concludes.

II. Background

Chinese rural resettlement follows the same guidelines regardless whether at the national level under the banner of community-based development and poverty alleviation or at the more local level where municipal governments convert rural-land to urban land to promote the local economy. In general compensation packages and redesignated areas developed for displaced households have to follow the guidelines of the Land Administrative Law as well as other national policies.

The procedure for requisitioning rural land for the purpose of urban expansion in China is briefly summarized as follows: A private company makes a proposal to use existing farmland, which must then be verified by the local municipal land administrative department who will then obtain approval from the State Council and local municipal government. Once the proposal is approved, the municipal government announces the land requisition decision and offers a compensation plan for the affected villages. Once all the villagers ‘agree’ to transfer the ownership of the land based on the proposed compensation, the land is considered requisitioned by the local government. For villagers whose farmlands are requisitioned, they will receive the agreed upon compensation. For villagers whose housing is also requisitioned, they would need to evacuate from the village and relocate to a different site before a certain stipulated date. Lastly, the local government leases the land to the private company for its proposed use at the agreed upon terms.

The resettlement project in Qingdao

We conducted this study over four years in a rural area located on the outskirts of Qingdao (Shandong, China), where the manufacturing base of a joint-venture was built. City J has been chosen out of four competing cities by the state as the location of the manufacturing base of a well-known international car manufacturer and its local counterpart at the state level. To avail the land for the base, the municipal government of City J requisitioned 27,303 mu of rural land, resulting in the relocation of eight Han villages (altogether 1513 households). The advantage of studying these villages that are in close proximity to one other allows the researchers to discount the impact that geographical differences play in their initial assessment of satisfaction. As these villagers main activity is agricultural, livelihood differences between the villages vary little as well.

Qingdao is one of the 15 free trade zones in China with capital investments from over 40 countries, therefore the local government has extensive experience with handling resettlement issues. It is important to note that in China, the requisition of rural land requires the land to be converted from collective-owned to state-owned, a process in which the village leadership team plays a vital role. In principal, all the villagers should sign the consent to be relocated and sell the land under their use at the agreed price before the conversion of ownership can take place. For requisitioned farmland, villagers would receive direct cash compensation. For requisitioned housing land, villagers could choose to receive either in kind or cash payouts. Upon signing away their consent, the villagers had to leave their home and move immediately to alternative housing of their own arrangement.Footnote2

In our study, the municipal government not only followed the national guidelines to award monies for land compensation but they also included several price adjustments to account for the higher prices warranted through urban land sales in this cosmopolitan city. In this way, based on an earlier study where researchers carried out interviews during the resettlement process (Huang et al. Citation2021), they found that most of the villagers (from the selfsame villages in our current study) were not unhappy about the land compensation price. Another feature of the resettlement in our study was that villagers had the opportunity to sign contracts with the government. This in principle protected them against certain default risks as well as stipulated late penalty clauses for the handing over of apartments if the villagers opted for land-to-land compensation. Part of the compensation provided a 10-month stipend awarded to each household to cushion the relocation costs. The contracts stipulated that apartments would be handed over after three years.

Only when all villagers were evacuated, the task of the village officials are considered completed. For the current project, when first announced, the consent signup period was slated for 30 days, but the time frame was shortened to 10 days with a short notice.Footnote3 An initial survey was conducted with villagers during this 10-day period which investigated the support levels and signing decision and its correlation with the prosociality of village leaders. Four years later, our study carried out follow-up telephone interviews with those original responders as well as additional social contacts provided in the original study in order to understand how these land-lost villagers had coped with the initial displacement, whether they had relocated to the promised apartments and whether their standard of living had improved after resettlement.

This paper provides a case study examining the well-being of the displaced community where the larger goals of economic development were largely met as a consequence of the resettlement. Firstly, a world class factory facility was built on the site of the requisitioned land, boosting the local economy. Secondly, the multinational company actively practised corporate social responsibility and provided a percentage of land-lost villagers with either technical or custodial jobs. Therefore unlike previous studies which found that farmers who found non-farm work were most likely in sectors that were temporary (Chimhowu and Hulme Citation2006; Souksavath and Nakayama Citation2013; Webber and McDonald Citation2004), our study presents a case where those who found jobs as a result of the new factory were likely employed on a more permanent basis. Thirdly, the promised apartments did materialise in this project and by the time of this study, 94.8% of the respondents had already collected the keys to their apartments.

Sustainable livelihoods of displaced land-lost farmers

The process of urban development comes with it many challenges for policymakers examining the livelihood outcomes of displaced land-lost farmers. Socioeconomic problems for displaced people as defined by the United Nation’s sustainable development goals, especially SDG 11 include impoverishment risks such as food insecurity, loss of homes and livelihoods, loss of culture and environments as well as income insecurity, marginalization and increased risks of morbidity. While adequate compensation might be made to land-lost farmers for their homes and farmland based on a fair market rate, measures which address these types of impoverishment risks should be part of the resettlement framework governing policymakers’ actions. Conceptually, we are interested whether displaced communities are able to secure better socio-economic outcomes post resettlement than prior. We can evaluate different aspects of well-being by considering the employment outcomes of these land-lost farmers, their provision of safe and sustainable housing, whether they enjoy higher household incomes after resettlement, and whether the household experiences health benefits, better food security, access to sustainable infrastructure and services, a better overall environment than previously enjoyed in the villages, and the ability to establish long term social and political networks. While no one framework can capture all elements that describe what it is to have a sustainable livelihood, but by examining it in this limited context allows us to make comparisons of households who have chosen to leave farm activities and pursue economic opportunities in urban settings (such as in our context) and to consider the lost farmlands as an asset ‘required to make a living to human, financial, physical economic infrastructure, and socio-political assets’ (Chimhowu and Hulme Citation2006). Once we can establish the creation or loss of these varied types of assets, it is important to understand which of these assets increase, decrease or play a limited role in promoting the well-being of displaced land-lost farmers. This is what we investigate in this paper.

Previous research investigating the livelihood outcomes of this vulnerable group of people have found (1) in cases where the displaced community continued to engage in farming activities, in many instances more than 50% of those affected were unable to attain the same production yields or incomes as with prior the resettlement (Kura et al. Citation2017; Yoshida et al. Citation2013; Souksavath and Nakayama Citation2013); (2) in cases where the displaced community found work in other sectors either to supplement farm incomes or to substitute for it, it was usually the ones who were most susceptible to idiosyncratic shocks like droughts and floods or had the opportunity to work in temporary sectors like construction or transport who engaged in these activities, however research shows that many reported lower satisfaction due to the loss of their original livelihoods (Sunardi, Gunawan, and Pratiwi Citation2013) or that these livelihoods were not sustainable either due to state sponsored supports (Chimhowu and Hulme Citation2006; Souksavath and Nakayama Citation2013) or that such sectors where employment was found were temporary (Webber and McDonald Citation2004).

III. Methodology

To establish the link between the group cooperation of village officials and its impact on the reported life satisfaction levels of the villagers four years after the resettlement, we obtained data through a lab-in-the-field public goods game experiment with village officials two months after the resettlement even, and telephone interviews with the villagers four years after the resettlement event. We detailed the public goods game with village officials and the follow-up survey with villagers in this section.

Public goods game

Two months after the consent-signing event and after all the villages were demolished, we arranged a training program for the village officials of the seven relocated villages, during which we conducted an incentivized public goods experiment. Administratively, 4–5 persons were elected and assigned as officials in each village, who worked together at all village-related matters including assisting in the land requisition. Over 80% of the registered village officials attended the training and the experiment. We conducted this lab experiment in the field according to the extra-laboratory experiment protocol as outlined in Charness, Gneezy, and Kuhn (Citation2013). In particular, the subjects were drawn from the relevant pool of local village officials and they were aware of their participation in an experiment although they were unaware of its purpose.

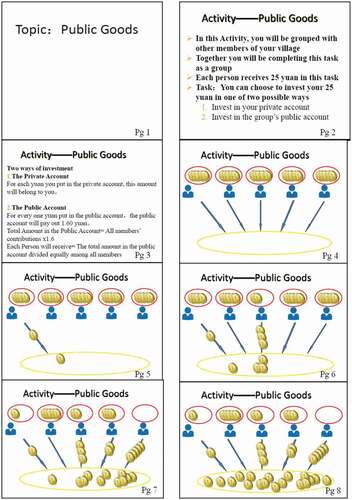

Considering the educational level of the participants, we conducted a one-shot public goods game using a pen and paper protocol. In the game, each subject was given 25 yuan as endowment and he/she had to decide how much to allocate to his/her personal account and how much to allocate to the group account. Money deposited in the group account would be multiplied by a factor of 1.6 and then equally distributed within the group. All protocols and parameters of the game were introduced using pictures and diagrams in a PowerPoint presentation.Footnote4 Control questions were included to test the participants’ understanding of the game, and we proceeded to the real game only when all participants had given the correct answers. The payment was paid in cash in a double-blind manner to each participant at the end of the training session.

A key feature of this public goods experiment is that each village official played with their coworkers from the same village. This variation allowed subjects within the group to remain anonymous whilst having some private information about the cooperativeness of their own group as a whole. In this sense, the contributions made by each participant might not reflect the traditional interpretation of ‘social preferences’ in that the game was played by a specific subject pool among their own peer group. Therefore, the contributions to the public account in this game reflected the level of group cooperation among village officials within the same village, which is a critical factor we hypothesize will affect the implementation of any village-related project. For further analysis, we used the average contributions of each group to measure the level of group cooperation of a village leadership team.Footnote5

Follow-Up survey with villagers four years later

Like previous studies examining the sustainable livelihood outcomes of displaced communities, we carried out one to one interviews with those affected several years after the resettlement event (Billig Citation2016; Kura et al. Citation2017; Sunardi, Gunawan, and Pratiwi Citation2013; Yoshida et al. Citation2013; Webber and McDonald Citation2004). While these studies use a convenience sampling methodology to track down affected villagers, we differ in our methodology by following up an initial random sample of villagers which had taken part in an earlier study during the signing window. By following the same contacts over a four year period,Footnote6 we are able to minimize sample selection biases in our study.Footnote7 All interviews were carried over the phone. Prior to our telephone interview, one member of the research team sent sms-es to all numbers in our sample. The message was as follows:

How are you? My name is XXX, from the Y Center, Z University. You were previously interviewed by us regarding your resettlement experience. Currently we have a few questions we would still like to ask you. I will call you over the phone in the next few days. Thank you for your participation.

This single researcher then individually called every number on the list in order to minimize the variation of responses due to interviewer bias in our sample. She then coded calls which were answered or left unanswered. Of those who answered, we further coded whether the respondent a villager affected by the resettlement or an unrelated partyFootnote8 or refused to entertain our request for an interview. Altogether we had a response rate of 38.59% of the original 187 villagers who had been interviewed (71 villagers) and 18.6% of the 253 social contacts (46 villagers). From our pool of telephone numbers, 48.8% of the numbers were either disconnected numbers, numbers which continually remained unanswered or were no longer registered to the original villagers from the resettlement villages. Each interview took about five to ten minutes.Footnote9 79.5% of the respondents had moved to the promised apartments, many of these households had been residing in temporary living arrangements and had moved in order to save money. This was in spite of the fact that they were handed over the apartments without them being connected to the national power grid or main water lines. Of particular note is the fact that the handover took place in winter and the apartments were also not yet connected to the central heating system of the city. Hence, we code two dummies, apartment – delivered and apartment – residing to describe households which have received the promised apartments at the time of the interview and those who have chosen to stay in those apartments to control for the impact this might have on resettled households’ satisfaction levels.

Survey questions controlling for possible sustainable livelihood challenges facing these households consisted of six distinct categories: questions related to current coping strategies by the household and income sources, the current financial assets owned by the family, current health and human capital, social and political ties, and lastly their current life satisfaction levels. We highlight the key variables and the questions that villagers were asked in where we report the summary statistics. Each question sought specific information about the household (members comprising the family unit prior to the resettlement) from which the respondent belonged to. As highlighted by other researchers, there is no consensus about how to gauge or measure the different factors which constitute a sustainable livelihood, nor is there a clear understanding of which factor may weigh more toward increasing the displaced household’s well-being (Bebbington Citation1999; De Haan and Zoomers Citation2005; Scoones Citation1998, Citation2009). In order to ensure the maximum coverage of respondents based on our original sample, and given that we were not being able to offer financial incentives for participation owing to the sheer physical distance between us, our survey questions involved little time cost (between 5–10 minutes) and only required general attitudinal impressions of higher, lower or similar levels of well-being in these broad six categories (thereby lowering the cognitive cost of recall). We then use a multinomial logistic regression analysis using villagers’ reported life satisfaction as the dependent variable and we examine how differences to variables in these six distinct categories affect their well-being.

Table 1. Average PGG contributions by village leadership team (by village)

Table 2. Summary statistics of villagers’ survey

Hypothesis

We postulate that the characteristics of the leadership team can help prepare a community to better access potential risks and mitigate challenges as they adapt to life after resettlement. In the context of resettlement, we have the following hypothesis regarding the cooperativeness of village officials.

The satisfaction hypothesis

The higher the average contributions of the village officials in the public goods game, the higher the percentage of villagers who report higher current life satisfaction four years after resettlement.

The positive relationship between the public goods contributions of the village officials and their life satisfaction levels might occur through three possible channels. First, at the group level, higher average contributions implies a more prosocial leadership team. A prosocial leadership team would care that the terms of resettlement were favorable to the villagers and might ensure that the process was transparent and that due dilligence was carried out to minimize rent-seeking and corruption at each village level. To expand on this issue, one of the key jobs of the village leaders was to measure the landholdings of each farmer. This is done together with an independent contractor hired by the municipal government. As compensation is given based on the use of land, village leaders play a vital role in determining whether higher or lower compensation is given which will directly impact compensation incomes and future savings of these households. Both of these factors play a role in promoting a sustainable livelihood.

Second, at an individual level, cooperative officials would be more likely to help villagers overcome obstacles after the resettlement, especially if there were contract disputes. On the other hand, village officials who contributed less to the public good might be more self-interested in their daily work and lives, such that they might be disinterested in village matters post resettlement. They might be less concerned with the difficulties faced by the community and this may lead to a higher number of unsatisfied villagers. In the case of our villages, there were instances where certain villages upon signing the resettlement contracts immediately proceeded to demolish buildings in the following few days, thereby resulting in many households scrambling to find alternative housing in a very short time frame. This might impact the unnecessary drawing down of financial resources at a vulnerable time. By reducing the costs of relocation and other transaction costs associated with the resettlement expenses, households are able to conserve resources, reduce frictions and improve social ties and possibly also avoid health risks associated with resolving conflicts post resettlement.

In addition, research on leader-follower behavior has shown that cooperative leaders who are perceived to work in a group-oriented manner rather than for purely self-interest, are trusted more by followers (Van Knippenberg and Van Knippenberg Citation2005) and this greater trust translates to followers having more favorable perceptions of their leader, while displaying a greater willingness to follow the leader’s requests, motivating conditional cooperators (Dannenberg Citation2015; Gächter et al. Citation2012; Güth et al. Citation2007) and being motivated to act in a way that benefits the group (Hogg Citation2001; Van Knippenberg and Hogg Citation2003). Village leaders, being cooperative themselves, would set an example for the villagers to be cooperative as well and we hypothesize that this would translate with villagers themselves receiving more help from other villagers. Alternatively, less prosocial leaders might promote a culture of individualism and working toward one’s own benefit only in the communities they serve, hence such villagers might seek short-term gains over community interests.

IV. Results

A brief summary of our empirical results is that villagers’ life satisfaction levels are correlated with village officials’ average public goods contributions four years after the resettlement. We also control for post resettlement outcomes such as whether relocated families who had lost farm jobs had managed to find other work, whether they had family networks whom they interacted face to face with regularly, whether the apartments had been delivered to them as well as other variables related to the sustainable livelihood framework. In particular, we find that better sustainable livelihood outcome measures such as higher savings levels, better health and greater accumulation of assets predict how well villagers have adapted to post resettlement life. Owing to the fact that even after controlling for these post resettlement outcomes and other possible sustainable livelihood measures, we still find that the prosociality of the village leaders evaluated four years earlier still has significant explanatory power in predicting life satisfaction in the present study lends support to the relevance of laboratory preference measures to actual welfare in the field. The findings are described in detail below.

Summary statistics

provides the summary statistics of the village officials from the participating villages. We arrange the villages into groupings ranked according to their average contributions in the public goods game. We conducted a public goods game with the village leaders from the affected villages. shows that 3–6 village officials participated in the experiment. These officials were elected in the current tenure when the resettlement project took place. According to the local rules, a village committee was composed of 5 key positions: a party branch secretary, a village head, a head of the woman’s association, a mediator and an accountant. Under this backdrop, the number of participants shows that a majority of the village committee members participated in the experiment.

Average contributions to the public goods varied from 40% to 100% of the endowment. To simplify the analysis, we group the villages into three categories based on their officials’ contributions in this experiment: low contributions (40%-43%), medium contributions (67%-77%), and high contributions (100%). We have 2 villages, 4 villages, and 1 village in each respective category. also presents the demographic information of the participants, including gender composition, education, age and service years. Regression analyses show that none of these factors statistically influence individual’s contributions in the public goods game.

presents the descriptive statistics of the main variables from the one-on-one telephone survey based on these three groupings. As described in Section 3.2, of all the mobile numbers we contacted, we had a total of 22% of the villagers who refused to be interviewed. We examined whether the refusal rate was different between low, medium and high PGG villages and found that it was not significantly different (p-values between low and medium PGG villages was 0.895, for low and high PGG villages it was 0.442 and for medium and high villages it was 0.62). Satisfaction provides an individual villager’s assessment of his household’s current overall situation compared to their situation before resettlement which is coded on a three point scale: 1 denotes ‘worse off’, 2 denotes ‘no change’ and 3 denotes ‘better off’. On average, villagers rated their satisfaction level as close to 2, implying that an average household was indifferent between living in the village community or staying in an urban apartment complex. By village groups, we see that the vilage with the highest contributions report the highest satisfaction levels.

Variables of individual demographics include age, male, farmer and related to that, if the respondent had members in his household who had been farmers, whether they had found non-farm work (found work) after resettlement. The average age of the interviewees was 51.34 years old and 74% of them were males. Farmer is a dummy variable describing whether the respondent’s household had family members directly involved in farming before resettlement. Resettlement should impact the livelihoods of farmers the most because they would be losing their agricultural land and therefore losing their long-term source of income (52% of our respondents). Of these land-lost farmers, 27% found jobs in non-farm work afterward. In our context, the new factory did hire some of the villagers: for the younger workers with at least high school education, they found work on the factory floor; while older workers with lesser qualifications found jobs as cleaners and security personnel. However opinions differed in our telephone interviews as to the availability of these jobs. Some of the respondents felt that there was a lack of jobs for everyone by the factory while others indicated that it was the attitude of the villagers themselves which was lacking in their active search for a job.

Variables that capture factors which contribute to a sustainable livelihood include income, asset wealth, savings, health, and social ties. income higher and income lower are two dummy variables indicating whether the respondents felt that their household income had gone up, or had worsened compared to before resettlement. In our sample, we find that 29% of those in low PGG villages reported higher incomes than in either medium PGG villages (3%) or high PGG villages (8%); while only 23% of those in low PGG villages reported lower incomes than in either medium PGG villages (39%) or high PGG villages (33%). This suggests that these villages secured better job opportunities than the other villages. This may be related to the fact that while these three groups of villages had similar percentages of respondents with household members engaged in farming, however in low PGG villages, 35% of these land-lost farmers managed to find non-farm work as compared to medium PGG villages (23%) and high PGG villages (29%).

Assets higher and assets lower are two dummy variables indicating whether the respondents felt that their household asset levels had gone up, or had worsened compared to before resettlement. This would include property holdings as well as paper assets. Savings higher and savings lower are two dummy variables indicating whether the respondents felt that their household savings’ accounts had gone up, or had gone down compared to before resettlement. Health higher and health lower are two dummy variables indicating whether the respondents felt that the members in their household has experienced improving or worsening of their health levels compared to before resettlement. There were many cases of households with very old family members who had died during this upheaval period. Many of their family members registered unhappiness that the resettlement had happened during this vulnerable time. Socialties better denotes that the respondent felt that his households’ social and political ties had improved after moving into an urban environment. We had other variables which we had solicited from interviewees such as their evaluation of their accessibility to infrastructure and amenities,Footnote10 whether they were living near relatives and the frequency of their visits, as well as household purchases like cars. All these variables had negligible effect in all our analyses and therefore are not reported.

. reports the Type 1 error adjusted p-valuesFootnote11 (using Boniferroni, Scheffe and Sidak adjustments of the familywise error rates) when making pairwise comparisons between high PGG, medium PGG and low PGG villages. We show in , that the respondents in these three groups are not significantly different from each other (approximately 51–52 years old, 74% male, 52% were previously engaged in farming in the village, 23–29% had found work in the new urban environment, 17–29% were residing in the new apartments.).

Table 3. Pairwise comparisons between groups of villages by contribution rates: adjusted p-values

We can see from . that there is no systematic relationship between PGG contributions and other demographic variables, post resettlement outcomes or sustainable livelihood measures such as income, asset wealth, savings, health capital and social/political ties between the three groups. From our pairwise comparisons, we can see that while high PGG villages had a significantly higher probability of higher life satisfaction than medium PGG villages but this is not the case when comparing high or medium PGG villages with low PGG villages. We also find that while low PGG villages were more likely to report higher income levels after resettlement than either medium or high PGG villages − 29% in low PGG villages reported high household income compared to 3% for medium PGG villages and 8% for high PGG villages, but there is no such correlation when considering between medium and high PGG villages. One possible reason for this occurrence might be, as suggested earlier, that low prosocial leaders might promote a culture of individualism and self-interest among their own constituents which could be conducive to entrepreneurship or opportunism. While we can see that in , only 17% of those in the high PGG villages were residing in the apartments at the time of the interview while 29% of the low PGG villages were residing in the apartments, the reported p-values in show that there are no significant differences. also establishes that the level of group cooperation of village leaders did not significantly affect the sustainable livelihood outcomes of displaced villages four years in the future.

Multinomial logistic regression

In this section, we use a multinomial logistic regression to study the effect of a contextual variable at village-level (PGG) over individual results.

presents our results. We include all our variables of interest such as the public goods contribution rate of village leaders, PGG, the demographic variables such as age, gender and whether the villager had been a farmer, as well as post resettlement outcomes such as whether villagers had found non-farm work after resettlement, whether they had close interaction within family networks,whether they had been delivered the promised apartments and were currently residing in them, as well as villagers’ subjective evaluation of whether they felt their household income, financial asset wealth, health status and social and political capital had increased or decreased after resettlement. We then compare these variables for villagers whose reported satisfaction levels were ‘no change’ and ‘better off’ with the base outcome of being ‘worse off’. We find that higher mean public good contributions of villagers’ village leadership team significantly predict households’ higher satisfaction levels (p0.05). For every 1% increase in PGG contributions made by the village leadership team, households had a 2.48–2.52% higher odds of reporting ‘no change’ compared to being ‘worse off’ (column 5), and had a 4.02–4.62% higher odds of reporting ‘better off’ compared to being ‘worse off’ (column 7). Wald and likelihood ratio tests all confirm that our main variable of interest, PGG, significantly explains reported satisfaction levels even after controlling for the influence of other sustainable livelihood measures. Based on the results gleaned from and , we find that PGG variable does not explain the different sustainable livelihood outcomes of villagers however they do predict the level of life satisfaction they report, highlighting the relevance of the prosociality of leaders as an independent explanatory variable.

Table 4. Results of multinomial logistic regression (N = 117)

Other interesting side findings are that males are more likely to be unsatisfied with their current life situation than females and tend to report ‘no change’ or ‘worse off’ rather than ‘better off’, as well as those who perceive that their households’ savings have fallen significantly in the four years report lower satisfaction levels. Several control variables also predict those who report higher satisfaction levels, such as assets higher, health higher which are all significant at 1% level. For respondents who perceive their households as having more asset wealth and are healthier than before resettlement are more likely to report higher satisfaction levels after resettlement.

V. Policy considerations

Our paper therefore presents the practitioner as well as the academic, relevant insights into promoting sustainable livelihood strategies in order to improve the well-being of communities that are displaced even when benign policies are in place.

The key contribution of our paper is that we provide evidence that a significant, positive relationship exists between the prosociality of village leaders and the self-reported levels of life satisfaction of resettled villagers. We show that even accounting for higher or lower factors under a sustainable livelihood framework, the prosociality of the leadership team is still predictive of higher levels of life satisfaction four years after resettlement.

This opens a new avenue for policymakers to focus on – how to consider social values and moral incentives in the design of public policy. On the one hand, the selection of intrinsically prosocial village officials may be an important but often neglected area to improve on. This involves setting the appropriate criteria with which one can enter the candidate pool before being elected to office. While this sounds extreme especially in a village setting but it may be as simple as mandatorally requiring candidates to take part in government organized poverty allevation programmes and taking part in community events. Another area of focus would be in the preparation of officials. Within the existing framework of training and upgrading programmes, village officials can be exposed to more team-building exercises and the best practices of highly effective teams. Lastly there should be extrinsic incentives in place which reward qualities of cooperation among the village leadership community. This may be in the form of setting appropriate key performance indicators which promote a culture of cooperation and rewarding team performance rather than individual performance, for example, rewarding teams for high scores in villagers’ evaluations of their performances. By selecting, preparing and incentivizing leaders to be more prosocial, we show that community welfare is significantly improved not only in the short-run but in the medium term as well.

Lastly, our study investigated the different sustainable livelihood measures and find that only asset wealth, savings and health significantly improve the well-being of resettled villagers.

VI. Conclusion

In this paper, we examine the relationship between the levels of group cooperation of village officials and the well-being of displaced villagers four years after resettlement. We measure the group cooperation of village officials using a public goods game experiment in the field, and measure villagers’ satisfaction levels using self-reported surveys with villagers conducted four years later. The results show that the public good contributions made by the village officials are positively correlated with villagers’ subjective evaluations of higher life satisfaction in the city compared to life in the village. This correlation between village officials’ average contribution level and their constituencies’ level of life satisfaction is both robust and significant even after controlling for certain demographic characteristics, whether it was a farming household, whether those who had lost farm jobs had found non-farm work, whether the household was currently residing in the new apartments and accounting for other measures under a sustainable livelihood framework.

Our results suggest that the social preferences elicited from the lab have implications in the real world: village officials who were more cooperative in the experimental game increased the welfare of their constituencies – their own constituencies evaluated their satisfaction level post-resettlement as higher than pre-resettlement levels. This study lends further support for the usefulness of laboratory experiments in predicting welfare outcomes in the field, especially the well-being of those whom the subjects interact with.

This paper has strong implications for the Chinese policymaker as well. Rural land requisition and village resettlement are common strategies to spur growth in Chinese cities. This study shows that even in the best of cases, where the social economic interest of the relocated population has been considered, there are still many potential sources of frustration which could be mitigated through proper institutional oversight. In our study, we find that there are critical junctures in the resettlement process where unexpected hardship, and unanticipated expenditures draw down household financial assets, as well as individual savings which might well impact the overall health capital of displaced households. Many of these hardships could have been cushioned if the municipal government had better managed their information delivery systems and provided monetary assistance to at-risk households at these critical junctures – either through non-interest loans or timely compensation payouts for their failure to meet contractual obligations. Beyond this, in order to ensure that villagers are able to enjoy a similar standard of living in these newly developed neighborhoods, governments could also consider including higher levels of subsidies for basic amenities like water, heating and electricity while these new communities are being built up. For households with aged parents or grandparents, higher health benefits should be formally provided in order to arrest the stresses of relocation.

Lastly, our work explores a new and promising area for policymakers. We show that the choice of leaders who have prosocial preferences have strong spillover effects on members within their own constituencies, reflected through higher levels of satisfaction registered four years later by the villagers after the resettlement. This effect is independent of other measures of sustainable livelihood and serves as a complement in improving the welfare of displaced communities. Policymakers should consider providing more team building programmes as well as explicit extrinsic incentives to promote a culture of cooperation among its local leaders.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial assistance of the China’s Ministry of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Fund (19C10422042), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (ZR2019QG003) and the Fund of Taishan Scholar Project, Shandong, China(TS20180101).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Studies have shown that certain demography characteristics of village leaders: age, tenure and educational attainment of either the village heads and the party secretaries, are useful predictors of the level of rent-seeking and successful implementation of public projects (Brandt, Rozelle, and Turner Citation2004; Park and Wang Citation2010). Other factors such as leaders’ positive experiences with international aid (Macours and Vakis Citation2014), leaders’ social ties within the community (Tsai Citation2007; Xu and Yao Citation2015) are also found to affect the outcome of village leaders’ community service. Other studies consider the quality of the leadership team in these village committees and have found that higher quality village committees were found to bring more benefits to both rich and poor households (Park and Wang Citation2010).

2 In some other cases, the affected villagers were informed and expected to sign the relocation consents when the land had already been sold to the government (see Xue, Wang, and Xue Citation2013).

3 Originally, an early bird bonus of 8,000 yuan was awarded to those who signed the consent and relocated immediately within 10 days given a 30-day time frame. When the signup window was shortened to 10 days, all those who managed to sign and leave within the required period received an added 2000 yuan for an overall bonus of 10,000 yuan.

4 The slides (Figure A1) and the decision sheet (Figure A2) we used are found in the Appendix.

5 Using the average of group characteristics is common in the study of group decisions (see a meta-analysis of Stewart Citation2006 that surveys the influence of group characteristics on group processes in a variety of task environments). In the cited studies, the average of individual abilities or demographic characteristics were used to characterize the group’s ability (see Bacon, Stewart, and Stewart-Belle Citation1998; Bantel and Jackson Citation1989; Wegge et al. Citation2008). Deeter-Schmelz, Kennedy, and Ramsey (Citation2002) find that a team’s mean self-reported assessment of cohesiveness and cooperation predicted team performance and Neuman, Wagner, and Christiansen (Citation1999) find that a team’s average score on agreeableness in the Big 5 personality factors predicts team performance. Others studies used in psychology also use the means of individual characteristics in order to characterize team ability (see Wegge et al. Citation2008).

6 These respondents were first interviewed during the signing of the resettlement contracts, and they had given their mobile numbers as well as the numbers of their social contacts from the respective villages. Each responder was asked to leave one to four social contacts. Four years later, our research team contacted the survey participants from that original survey, as well as their social contacts.

7 Convenience sampling thus captures the majority who remain in designated locations and are thus easily tracked but are unable to account for villagers who have left the area or are unable to be contacted. This may present an overly optimistic or overly pessimistic picture of the outcomes of resettlement depending on whether those who have left the area are better off or worse off.

8 It is likely that households who had left the area and moved further elsewhere would change their numbers and hence their previous number would be allocated to new users by the telecomunications company.

9 Although there were many responders who took this chance to voice out their dissatisfaction or grievances and therefore spent half an hour detailing their families post-resettlement experiences.

10 This is a variable which we had initially felt might be a pull factor for supporting resettlement, however our survey responses showed that although the new apartments had been completed but without reliable water, electricity and central heating, almost all respondents felt dissatisfied with their access to amenities.

11 By making these adjustments, we reduce the inflation of Type 1 error of finding a false positive.

References

- Bacon, D. R. K. A. Stewart, and S. Stewart-Belle. 1998. “Exploring Predictors of Student Team Project Performance.” Journal of Marketing Education 20 (1): 63–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/027347539802000108.

- Balliet, D. C. Parks, and J. Joireman. 2009. “Social Value Orientation and Cooperation in Social Dilemmas: A Meta-Analysis.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12 (4): 533–547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209105040.

- Banerjee, A. V. and E. Duflo. 2009. “The Experimental Approach to Development Economics.” Annual Review of Economics 1 (1): 151–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.economics.050708.143235.

- Bantel, K. A. and S. E. Jackson. 1989. “Top Management and Innovations in Banking: Does the Composition of the Top Team Make a Difference?.” Strategic Management Journal 10 (S1): 107–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100709.

- Barr, A. M. Lindelow, and P. Serneels 2004. To Serve the Community or Oneself: The Public Servant’s Dilemma. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Bazzi, S. A. Gaduh, A. D. Rothenberg, and M. Wong. 2016. “Skill Transferability, Migration, and Development: Evidence from Population Resettlement in Indonesia.” The American Economic Review 106 (9): 2658–2698. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141781.

- Bebbington, A. 1999. “Capitals and Capabilities: A Framework for Analyzing Peasant Viability,rural Livelihoods and Poverty.” World Development 27 (12): 2021–2044. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00104-7.

- Ben-Ner, A. 2013. “Preferences and Organization Structure: Toward Behavioral Economics Micro-Foundations of Organizational Analysis.” The Journal of Socio-Economics 46: 87–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2013.08.003.

- Billig, M. 2016. “Effects of the Forced Resettlement of a Community from an Agricultural Settlement to a High-Rise Building.” GeoJournal 81: 123–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9604-4.

- Bouma, J. E. Bulte, and D. van Soest 2008. “Trust and Cooperation: Social Capital and Community Resource Management.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 56 (2): 155–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2008.03.004.

- Bowles, S. and S. Polania-Reyes. 2012. “Economic Incentives and Social Preferences: Substitutes or Complements?.” Journal of Economic Literature 50 (2): 368–425. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.2.368.

- Brandt, L. S. Rozelle, and M. A. Turner 2004. “Local Government Behavior and Property Right Formation in Rural China.” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 160 (4): 627–662. doi:https://doi.org/10.1628/0932456042776032.

- Cardenas, J. C. and J. Carpenter. 2008. “Behavioural Development Economics: Lessons from Field Labs in the Developing World.” The Journal of Development Studies 44 (3): 311–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380701848327.

- Cardenas, J. C. and J. P. Carpenter. 2005. “THREE THEMES ON FIELD EXPERIMENTS AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT.“ Harrison, G.W, Carpenter, J, and LisT, J.A (Ed.) In Field Experiments in Economics (Research in Experimental Economics, Vol. 10), pp. 71–123. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Carpenter, J. and E. Seki. 2011. “Do Social Preferences Increase Productivity? Field Experimental Evidence from Fishermen in Toyama Bay.” Economic Inquiry 49 (2): 612–630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2009.00268.x.

- Carter, M. R. and M. Castillo, et al. 2002. ”The Economic Impacts of Altruism, Trust and Reciprocity: An Experimental Approach to Social Capital.” Wisconsin-Madison Agricultural and Applied Economics Staff Papers 448.

- Cernea, M. M. 1988. Involuntary Resettlement in Development Projects: Policy Guidelines in World Bank-Financed Projects. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Cernea, M. 1997. “The Risks and Reconstruction Model for Resettling Displaced Populations.” World Development 25 (10): 1569–1587. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00054-5.

- Cernea, M. 2000. “Risks and Reconstruction: Experiences of Resettlers and Refugees.“ Economic and Political Weekly. 35(41): 3659–3678.

- Cernea, M. 2006. “Development-Induced and Conflict-Induced Idps: Bridging the Research Divide.” Forced Migration Review. 261: 25–27.

- Cernea, M. 2008. “Compensation and Benefit Sharing: Why Resettlement Policies and Practices Must Be Reformed.” Water Science and Engineering 1 (1): 89–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1674-2370(15)30021-1.

- Charness, G. U. Gneezy, and M. A. Kuhn. 2013. “Experimental Methods: Extra-Laboratory Experiments-Extending the Reach of Experimental Economics.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 91: 93–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2013.04.002.

- Chimhowu, A. and D. Hulme. 2006. “Livelihood Dynamics in Planned and Spontaneous Resettlement in Zimbabwe: Converging and Vulnerable.” World Development 34 (4): 728–750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.08.011.

- Dannenberg, A. 2015. “Leading by Example versus Leading by Words in Voluntary Contribution Experiments.” Social Choice and Welfare 44 (1): 71–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-014-0817-8.

- Dawley, S. 2007. “Making Labour-Market Geographies: Volatile ‘Flagship’ Inward Investment and Peripheral Regions.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 39 (6): 1403–1419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a3863.

- De Haan, L. and A. Zoomers. 2005. “Exploring the Frontier of Livelihoods Research.” Development and Change 36 (1): 27–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00401.x.

- Deeter-Schmelz, D. R. K. N. Kennedy, and R. P. Ramsey. 2002. “Enriching Our Understanding of Student Team Effectiveness.” Journal of Marketing Education 24 (2): 114–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475302242004.

- Ellingsen, T. and M. Johannesson. 2008. “Pride and Prejudice: The Human Side of Incentive Theory.” The American Economic Review 98 (3): 990–1008. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.3.990.

- Fehr, E. and A. Leibbrandt. 2011. “A Field Study on Cooperativeness and Impatience in the Tragedy of the Commons.” Journal of Public Economics 95 (9–10): 1144–1155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.05.013.

- Gächter, S. D. Nosenzo, E. Renner, and M. Sefton. 2012. “Who Makes a Good Leader? Cooperativeness, Optimism, and Leading-by-Example.” Economic Inquiry 50 (4): 953–967. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2010.00295.x.

- Gentry, B. S. 1997. “Managing Environmental and Resettlement Risks and Opportunities in Infrastructure.” Choices for Efficient Private Provision of Infrastructure in East Asia 961: 69.

- Güth, W. M. V. Levati, M. Sutter, and E. Van Der Heijden 2007. “Leading by Example with and Without Exclusion Power in Voluntary Contribution Experiments.” Journal of Public Economics 91 (5–6): 1023–1042. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.10.007.

- Hogg, M. A. 2001. “A Social Identity Theory of Leadership.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 5 (3): 184–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_1.

- Huang, K. J. Li, R. Cheo, and Y. Qiao. 2021. ”Analysis of Factors Affecting Villagers’ Cooperation in House Demolition: Based on Field Study and Behavioral Experimental Study of 7 Villages.” China Economic Studies 1: 67–81. [In chinese].

- Irlenbusch, B. and D. Sliwka. 2005. “Incentives, Decision Frames, and Motivation Crowding Out-an Experimental Investigation”. Technical report.

- Kagel, J. and P. McGee. 2014. “Personality and Cooperation in Finitely Repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma Games.” Economics Letters 124 (2): 274–277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.05.034.

- Karlan, D. S. 2005. “Using Experimental Economics to Measure Social Capital and Predict Financial Decisions.” The American Economic Review 95 (5): 1688–1699. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/000282805775014407.

- Kinsey, B. H. and H. P. Binswanger. 1993. “Characteristics and Performance of Resettlement Programs: A Review.” World Development 21 (9): 1477–1494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(93)90128-V.

- Kosfeld, M. and D. Rustagi. 2015. “Leader Punishment and Cooperation in Groups: Experimental Field Evidence from Commons Management in Ethiopia.” The American Economic Review 105 (2): 747–783. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120700.

- Kura, Y. O. Joffre, B. Laplante, and B. Sengvilaykham. 2017. “Coping with Resettlement: A Livelihood Adaptation Analysis in the Mekong River Basin.” Land Use Policy 60: 139–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.10.017.

- Leibbrandt, A. 2012. “Are Social Preferences Related to Market Performance?.” Experimental Economics 15 (4): 589–603. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9315-y.

- Macours, K. and R. Vakis 2014. “Changing Households’ Investment Behaviour Through Social Interactions with Local Leaders: Evidence from a Randomised Transfer Programme.” The Economic Journal 124 (576): 607–633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12145.

- McClintock, C. G. and S. T. Allison. 1989. “Social Value Orientation and Helping Behavior.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 19 (4): 353–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1989.tb00060.x.

- Mischkowski, D. and A. Glöckner. 2016. “Spontaneous Cooperation for Prosocials, but Not for Proselfs: Social Value Orientation Moderates Spontaneous Cooperation Behavior.” Scientific Reports 6 (1): 1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21555.

- Neuman, G. A. S. H. Wagner, and N. D. Christiansen 1999. “The Relationship Between Work-Team Personality Composition and the Job Performance of Teams.” Group & Organization Management 24 (1): 28–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601199241003.

- Park, A. and S. Wang. 2010. “Community-Based Development and Poverty Alleviation: An Evaluation of China’s Poor Village Investment Program.” Journal of Public Economics 94 (9–10): 790–799. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.06.005.

- Pham, H. T. A. Van Westen, and A. Zoomers. 2013. “Compensation and Resettlement Policies After Compulsory Land Acquisition for Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Policy and Practice.” Land 2 (4): 678–704. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land2040678.

- Pletzer, J. L. D. Balliet, J. Joireman, D. M. Kuhlman, S. C. Voelpel, P. A. Van Lange, and M. Back 2018. “Social Value Orientation, Expectations, and Cooperation in Social Dilemmas: A Meta–analysis.” European Journal of Personality 32 (1): 62–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2139.

- Proto, E. and A. Rustichini. 2014. Cooperation and Personality. Technical report.

- Reddy, G. E. Smyth, and M. Steyn. 2017. Land Access and Resettlement: A Guide to Best Practice. London: Routledge.

- Scoones, I. 1998. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis. Technical report.

- Scoones, I. 2009. “Livelihoods Perspectives and Rural Development.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (1): 171–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820503.

- Scudder, T. 2012. ”Resettlement Outcomes of Large Dams.” In Impacts of Large Dams: A Global Assessment. Water Resources Development and Management, edited by C. Tortajada; D. Altinbilek, and A. Biswas. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 37-67.

- Souksavath, B. and M. Nakayama 2013. “Reconstruction of the Livelihood of Resettlers from the Nam Theun 2 Hydropower Project in Laos.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 29 (1): 71–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2012.738792.

- Stewart, G. L. 2006. “A Meta-Analytic Review of Relationships Between Team Design Features and Team Performance.” Journal of Management 32 (1): 29–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305277792.

- Sunardi, B. J. M. Gunawan, and F. D. Pratiwi. 2013. “Livelihood Status of Resettlers Affected by the Saguling Dam Project, 25 Years After Inundation.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 29 (1): 24–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2012.738593.

- Tendler, J. and S. Freedheim. 1994. “Trust in a Rent-Seeking World: Health and Government Transformed in Northeast Brazil.” World Development 22 (12): 1771–1791. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)90173-2.

- Tsai, L. L. 2007. “Solidary Groups, Informal Accountability, and Local Public Goods Provision in Rural China.” The American Political Science Review 101 (2): 355–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055407070153.

- Tuval-Mashiach, R. and R. Dekel. 2012. “Preparedness, Ideology, and Subsequent Distress Examining a Case of Forced Relocation.” Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress and Coping 17 (1): 23–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2011.578026.

- Van Knippenberg, B. and D. Van Knippenberg. 2005. “Leader Self-Sacrifice and Leadership Effectiveness: The Moderating Role of Leader Prototypicality.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (1): 25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.25.

- Van Knippenberg, D. and M. A. Hogg. 2003. “A Social Identity Model of Leadership Effectiveness in Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior 25: 243–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25006-1.

- Volk, S. C. Thöni, and W. Ruigrok 2012. “Temporal Stability and Psychological Foundations of Cooperation Preferences.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 81 (2): 664–676. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2011.10.006.

- Wakano, A. H. Yamada, and D. Shimamoto 2017. “Does the Heterogeneity of Project Implementers Affect the Programme Participation of Beneficiaries?: Evidence from Rural Cambodia.” The Journal of Development Studies 53 (1): 49–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1171847.

- Webber, M. and B. McDonald 2004. “Involuntary Resettlement, Production and Income: Evidence from Xiaolangdi, Prc.” World Development 32 (4): 673–690. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.10.010.

- Wegge, J. C. Roth, B. Neubach, K.-H. Schmidt, and R. Kanfer. 2008. “Age and Gender Diversity as Determinants of Performance and Health in a Public Organization: The Role of Task Complexity and Group Size.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (6): 1301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012680.

- Xu, Y. and Y. Yao. 2015. “Informal Institutions, Collective Action, and Public Investment in Rural China.” The American Political Science Review 109 (2): 371–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055415000155.

- Xue, L. M. Y. Wang, and T. Xue 2013. “Voluntary Poverty Alleviation Resettlement in China.” Development and Change 44 (5): 1159–1180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12054.

- Yoshida, H. R. D. Agnes, M. Solle, and M. Jayadi 2013. “A Long- Term Evaluation of Families Affected by the Bili-Bili Dam Development Resettlement Project in South Sulawesi, Indonesia.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 29 (1): 50–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2012.738495.