Introduction

Using inquiry as stance and narrative, I describe, explore, and analyze how the COVID-19 pandemic affected preservice school site observations and shaped my students’ burgeoning knowledge of art curriculum, and acknowledge how the pandemic impacted my own pedagogy. Inquiry as stance or practitioner inquiry (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation2009) acknowledges that teaching, researching, and administrative work experiences count as formative methods of discovery that generate new knowledge. Cochran-Smith and Lytle (Citation2009) believed that the practitioner inquiry framework “demonstrates how the process of theorizing can be the product of ongoing collaborative labor—often of school and university-based educators working in solidarity to alter the material conditions of teaching and learning” (p. 327). Likewise, Ledwell and Oyler (Citation2016) argued that teacher educators “construct valuable and sometimes untapped knowledge related to the many policy reforms they must navigate, interpret, and occasionally disrupt” (p. 123).

As teacher educators, we often share ideas about what’s working and what is not, and discuss how to react and adapt quickly. Curricular decisions are made in real time as seasoned teachers pivot, change plans, and redirect. In that generative, collaborative space, I write about the curricular challenges the pandemic created, including the impact on modeling good pedagogy, adapting when an entire mentoring and school site observation framework shifts precariously, and finding solutions to unexpected problems.

I draw from 18 preservice student observation reflections (180 reflection papers) and classroom discussions about remote art curriculum delivery, and I describe how our program responded to the challenging new reality, as well as what we can learn about teacher adaptability. Preservice student observation narratives illuminate and reveal the heart of good pedagogy—the ability to pivot, embrace flexibility, and find hope when disillusionment threatens: lessons their mentor teachers instilled with grace and humility.

Background and Context of Inquiry

While I was on sabbatical the previous spring and missed the chaos COVID-19 unleashed on education and my peers, it was important that my fall course be taught in person to build community within the new cohort. My curriculum development course is one of the first in which our new preservice art educators engage during our licensure program. Taught by a small group of core art education faculty, each of our classes has embedded school site observations ranging from 10 to 15 observation hours per course until teacher candidates complete 100 state-mandated prepracticum hours. As faculty, we dialogue and collaborate on preservice student progress and cohort concerns, and we take care to align curriculum, school site observation prompts, and other assignments.

I begin the curriculum development course by laying the foundations of the kinds of art instruction preservice students will be observing. I introduce backward design (Wiggins & McTighe, Citation2005) and share examples of how curriculum development works in tandem with contemporary art education frameworks (Acuff, Citation2016; Ballengee Morris & Staikidis, Citation2017; Barrett, Citation2017, Citation2019). One of the major assignments for the course is to identify a relevant and age-appropriate topic or issue to research and produce a robust unit plan. Because our preservice students observe in “Big Idea”–focused (Walker, Citation2001) and “Studio Thinking” or Teaching for Artistic Behavior (TAB) classrooms (Hogan et al., Citation2018), I introduce content on both curricular types before school site visits begin.

COVID-19 Instructional Challenges

We began the semester with in-person observations in place: two preservice students per school site,Footnote1 as our state fully intended that public schools would reopen for the fall semester. Once preservice students began exchanging information with their mentor teachers, it became clear that plans were in flux as individual districts made decisions about instructional delivery changes. Some preservice students would now be observing in districts that had switched to remote instruction or hybrid delivery situations. Two students observed in a suburban school that taught in person, but the art classroom had been moved to an outside tent with lunch tables.Footnote2 A few students went to physical art classrooms and assisted the teacher with digital delivery, while others never met their teacher in person and only joined the class remotely. Observations with authentic, tactile, interactive spaces and in-person art instruction were no longer possible for most preservice students.

Our university remained open but adhered to weekly COVID-19 testing and daily reporting of temperatures. Our classroom space was bizarrely structured; yellow caution tape blocked student access to common areas, and red “x” stickers on chairs denoted 6 feet of distance. I taught behind a red line taped across the carpet tiles, printed with a warning to keep away. Likewise, our department space looked like a crime scene with more yellow caution tape and piled-up chairs; our faculty offices were empty as we were restricted to no more than 20% occupancy. A university-hosted dashboard tracked student and faculty infection rates; we were warned that a spike of infections could close campus at any time. Everything felt compressed and off-kilter.

Pedagogical Realities

As a curriculum development course built around in-person observations, my original plans had to change—we had new terrain, new terminology, and new technology to understand. Introduction to TAB principles still occurred, but the experiences I was hoping they would observe did not match reality. Preservice students would not see TAB centers in action or hear students respond to instruction, watch as they made choices, or listen as they talked about artmaking. To supplement, faculty shared examples of art teaching content from YouTube and created links to art teacher websites to simulate classroom observations. However, many of the videos are instructor-centered due to privacy; students are filmed from behind, and while they can be heard, learners actively engaging in artmaking is limited.

Preservice students submit two-page narratives that focus on specific pedagogical or curricular issues faculty ask them to identify and reflect on while observing in the art classroom. The guiding prompts I used in the past no longer made sense. Depending on what a preservice student encountered on Zoom or in hybrid spaces, they could select a prompt that fit the circumstance and write from that viewpoint. Several topic areas, including how art classrooms function as spaces for learning, classroom management techniques, and timing of instruction, were reconsidered or discarded.

I typically read and respond to each preservice student’s reflection, drawing attention to course content and answering any questions about what they observed. Prompts also ask preservice students to consider their own ideas of how they might approach a situation or issue, and I give feedback on that as well. Ten observation reflections are due during the semester per student. The narratives I read were unlike any other semester, yet I needed to find a way to make sense of what they encountered and what we might learn from their observations. I kept track of themes and questions that appeared frequently and looked for ways to connect course content to the realities of pandemic art instruction.

Narrative Analysis of Preservice Observations

The 180 narratives I analyzed were vivid and well-described, but they tended to focus on how complex and disconnected remote art instruction appeared to my students. Many preservice students wrote about Zoom screens full of blank squares and kids who did not want to turn on their videos or only occasionally unmuted themselves. They wrote about mentor teachers trying myriad ways to entice engagement—those making heroic efforts to encourage art production, and who often forgave students who simply could not focus. Preservice students also found themselves questioning their assumptions as their preconceptions fell away. Instead of judging or questioning, we honored the hardships with which most mentor teachers were dealing and felt empathy for the kids trying to stay on track in digital teaching environments.

My preservice students struggled to feel connected to the art teaching career, only occasionally having an uplifting moment with a student in a Zoom breakout room. Others praised mentor teachers for not having thrown in the towel. I struggled, too, trying to find the right words to respond to their reflections. I wanted to acknowledge what they were processing and encourage them to look beyond the unfortunate obstacles in place. The word “flexible” became the thread running through so many reflections as mentor teachers wrestled with immediacies over learning goals. Based on the preservice reflections I read and to which I responded, our cohort made insightful observations on remote learning and student engagement. Fall 2020 also highlighted an educational system that remains uneven and troubled by issues of equity.

Access and Equity

Only a handful of preservice students observed in economically privileged schools, but the differences in relation to urban settings were significant. Wealthier suburban districts sent home bags full of art supplies, and they employed sophisticated digital platforms and technological advantages urban districts could not match. Students in suburban schools were expected to be present, meaning video on and unmuted, and to interact with each other as a group or in breakout rooms. Their teachers often taught from a familiar space, the art classroom, bringing normalcy and a sense of comfort. Mentor teachers readily assessed and tracked progress.

In urban schools, many lessons had to be tailored to limited supplies, like paper and pencils, or objects and materials found in students’ homes. Some days PowerPoint screen shares or video content made more sense as students struggled to stay on task. When it came to assessment, many mentor teachers simply preferred to reward verbal exchanges and effort, or give students extra points for turning on their video. One teacher, however, encouraged video to be off, mindful of privacy regarding her students’ home situations or their lack of supplies. Not all students had reliable internet access, or they had limited success with Zoom as an educational space.

Cohort discussions centered on equity issues and educational policy were heated, veering into the political—a space I tried to navigate with care. One thing was clear to them: Public education is not equal. I was surprised by how many students were not aware.

Digital Spaces

Preservice students found Zoom breakout rooms to be revealing places, in that behavior issues were more prevalent—but there was also evidence of students working collaboratively, offering support and encouragement to one another. The sharing of pets or pet visits lightened many Zoom calls. These were among the brighter moments about which preservice students wrote, including an anecdote about a student who took control of his teacher’s Zoom screen and then bartered for its safe return. The mentor teacher, to her credit, found it humorous. But she also mentioned feeling unsure, that her students understood technology at a deeper level than she did. Younger mentor teachers seemed more comfortable with technology than others. Many were already adept at filming art demos; producing video content for asynchronous learning; designing QR code access; and creating vibrant, engaging spaces for digital learning. Preservice students recognized the need to learn more about educational technology, including its usefulness once in-person learning returns.

Empathy

While preservice students marveled at their mentor teachers’ ability to adapt, multitask, and shift curricular plans to digital spaces, they were especially moved by their efforts to lead with care. Many observation narratives focused on a community of care; the teacher checked in with each student, offering kindness and understanding. Other preservice students discussed how much of this semester was about emotional needs. The stories they shared had little to do with art instruction or learning objectives; rather, they showcased the best qualities of good pedagogy—personal connection and empathy.

As I read each week’s observation reflections, I worked to alter our upcoming discussion topics as a way to allow a safe space to work through what preservice students had seen and heard. Our classroom discussions included student stress, economic disparity, regression, and skill loss (a common concern among mentor teachers). Privacy, both that of the teacher and their students; surveillance and recording; and the idea of parents listening in were also topics of concern. Preservice students were troubled by the idea of missing students; the kids who simply dropped off the radar during remote instruction—and how that could even happen. I tried to respond with honesty but worried about how dire it all seemed. Hope came from the empathy they observed.

Curricular Impacts

As a necessary instruction tool, online classrooms functioned as a reasonable alternative for a pandemic, but for teacher educators, it was a poor substitute for the observations we had planned. While preservice students admired their mentors’ patience and commitment, I increasingly worried about preservice students losing their passion for teaching. Significant learning moments were missing for my preservice students: impromptu chats with mentors between classes, assisting with setup, understanding how classroom spaces function, and the buzzing energy of artists at work. On-site observations are irreplaceable in this way, offering tangible understandings of pedagogy in action.

My pedagogy became more fluid. I updated curricular plans as the semester revealed itself as unstable, removing anything that veered toward busy work or added additional effort beyond the major assignments as fatigue began to set in. Due to COVID-19 guidelines, all assigned work defaulted to digital form instead of paper. I learned that I prefer reading and giving feedback on paper copies; as my digital world expanded, so did the hours I spent engaging with screens.

I set aside class time to work on assignments and was lenient about students who needed to leave early to find a place to set up for a distance delivery class. Over 70% of campus classes were remote by October; all were remote by November 24, including mine. Campus was eerily quiet; few students could be seen crossing outdoor spaces between classes. Not once did I encounter one of my colleagues. I began to feel disconnected from my academic home and disconnected from my research. I dreaded any Zoom-hosted committee work, and I worried that my lack of enthusiasm might impact my teaching.

Personal Impacts

My preservice students’ reflections about how their mentor teachers were coping came full circle at the midway point of the semester. Several of my students had been contact traced and had to Zoom in to class. One week, half of my class watched on Zoom as I taught the other half on campus. When I stopped to check in with my Zoom viewers, a set of blank squares stared back at me. The remote students were not engaging, and the students physically present were quieter than usual. Our dynamic community had been disrupted by the loss of so many peer voices. I left the classroom feeling unsettled, knowing personally how defeating it is to face a screen full of empty squares—talking and gesturing at nothingness. This reminded me of my belief that teaching is a reciprocal act. What sustains many of us who love teaching is the give-and-take—the intangibles, the connectedness of a community of learners at work, the knowledge that we are making purposeful steps toward understanding. It’s why we continue to do what we do, even in the face of insurmountable change. But the pandemic fatigue was real and closing in on me fast. I felt exhausted. And angry. So much of what I love about my job had been dismantled. I needed to reframe and adjust.

The following week I described my discomfort and anger about the semester to my preservice students. I explained my struggle with what I was missing and what I knew they were missing. I apologized for not being as prepared as I should have been. I explained that normally, I try to model good teaching by walking around, dropping in to small group work to chat, using voice modulation (teacher voice) and facial expressions to communicate. I was having trouble reading their faces, hearing their responses, and gauging interest because of masks and distancing. Humor, I learned, can fall flat when everyone is wearing a mask. I realized in that moment that even if they had been able to observe in person, the obstacles we were facing would exist in those spaces as well. Instead of anger, I embraced acceptance. We were all doing the best we could.

Conclusion

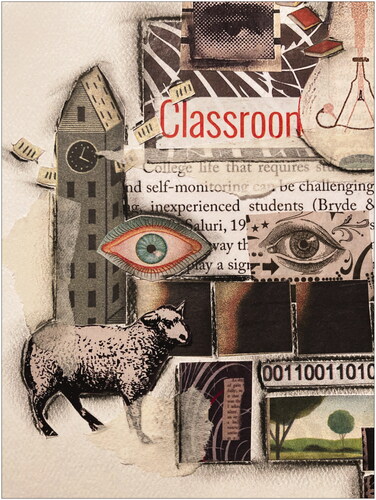

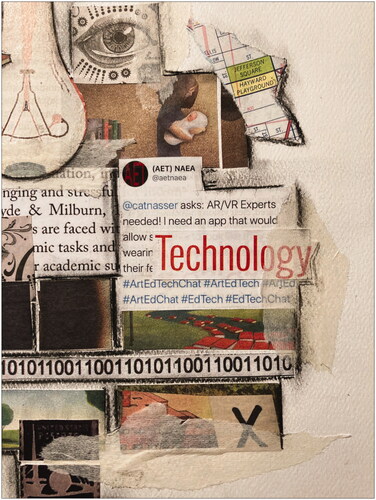

During the writing phase of this article, I spent time creating visual representations of the themes and ideas on which my preservice students reflected in their observations ( and ). The artwork in this article represents my commitment to arts-based inquiry. The artmaking process also acts as counterpoint to the strictures of traditional research writing, opening new spaces for meaning-making. Likewise, it was a welcome release from the difficulties of the semester, a reminder that artmaking can be healing.

While I continue to worry about how COVID-19’s impact may affect my preservice students’ ability to plan instruction, the unit plans they produced for my class were nicely designed. Expected learning outcomes and assessment strategies were strong enough, but there was also evidence that many critical needs did not translate. The timing of activities, classroom management strategies, and procedures for teaching lacked specificity because most preservice students did not have the benefit of seeing teaching in an art classroom space.

Teacher mentors remain the most important connection for preservice students. Literature on mentor teachers is robust (Ingersoll & Strong, Citation2011; Schwan et al., Citation2020; Shields & Murray, Citation2017), reminding us that the mentor teacher model is successful in its ability to bridge course content to authentic classroom pedagogy. Creativity happens in a noisy, chaotic space—a space in which mentor teachers thrive. Our students did not get the opportunity to see that magical alchemy in real time or learn about how art teachers harness and direct that energy and enthusiasm.

Finally, as a cohort, we talked about what we gained from this unusual semester. We felt grateful for having time to process our experiences as a group. We felt a shared commitment to checking in with each other. We acknowledged the need for digital competencies. We understood that students are influenced and impacted by their environments, that the disruption of familiar structures is destabilizing, but that this was also true for the art teachers we observed and for ourselves. We realized that being adaptive and flexible are critical skills—ones worth holding on to long after the pandemic fades. While my preservice students did not experience the usual rush of love for working with kids, they did develop a strong understanding that empathy is the cornerstone of great pedagogy. We send a collective hug to the mentor teachers who invited our preservice students into their classrooms; their transparency, courage, and humility are profoundly honored by this fellow educator and her students. We thank them for allowing our students to journey with them during a difficult but instructive time.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shari L. Savage

Shari L. Savage, Interim Department Chair, Associate Professor, Department of Arts Administration, Education & Policy, The Ohio State University in Columbus. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Preservice students observed in 10 K–5 grade-level settings, four 6–8 middle school settings, and four 9–12 high schools. No identifying information has been used.

2 The art room had been co-opted to enable more classroom space for others. Preservice students reported that large amounts of class time were devoted to cleaning and sterilizing spaces, and reminding students of safe distancing protocols.

References

- Acuff, J. B. (2016). “Being” a critical multicultural pedagogue in the art education classroom. Critical Studies in Education, 59(1), 35–53.

- Ballengee Morris, C., & Staikidis, K. (Eds). (2017). Transforming our practices: Indigenous art, pedagogies, and philosophies. National Art Education Association.

- Barrett, T. (2017). Why is that art?: Aesthetics and criticism of contemporary art (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Barrett, T. (2019). CRITS: A student manual. Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. Teachers College Press.

- Hogan, J., Hetland, L., Jaquith, D. B., & Winner, E. (2018). Studio thinking from the start: The K–8 art educator’s handbook. Teachers College Press; National Art Education Association.

- Ingersoll, R. M., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233.

- Ledwell, K., & Oyler, C. (2016). Unstandardized responses to a “standardized” test: The edTPA as gatekeeper and curriculum change agent. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(2), 120–134.

- Schwan, A., Wold, C., Moon, A., Neville, A., & Outka, J. (2020). Mentor and new teacher self-perceptions regarding the effectiveness of a statewide mentoring program. Critical Questions in Education, 11(3), 190–207.

- Shields, S., & Murray, M. (2017). Beginning teachers’ perceptions of mentors and access to communities of practice. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 6(4), 317–331.

- Walker, S. R. (2001). Teaching meaning in artmaking. Davis.

- Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). ASCD.