ABSTRACT

Objective: To appraise the methodological quality of studies on the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities for children presenting with gender dysphoria, including diagnosis and management.

Study design: A systematic review of 15 articles on psychiatric comorbidities for children diagnosed with gender dysphoria between the ages of two – 12 years.

Data sources: A systematic literature search of Medline, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Scopus and Web of Science for English-only studies published from 1980 to 2019, supplemented by other sources. Of 736 studies, 721 were removed following title, abstract or full-text review.

Results: Ten studies were retrospectively-oriented clinical case series or observational studies. There were few randomised, controlled trials. Over 80% of the data came from gender clinics in the United States and the Netherlands. Funding or conflicts of interest were often not declared. Mood and anxiety disorders were the most common psychiatric conditions studied. There was little research on complex comorbidities. One quarter of studies made a diagnosis by a comprehensive psychological assessment. A wide range of psychological tests was used for screening or diagnostic purposes. Over half of the studies diagnosed gender dysphoria using evidence-based criteria. A quarter of the studies mentioned treating serious psychopathology prior to addressing gender dysphoria.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Children with gender dysphoria are likely to experience profound psychological and physical difficulties.

Gender clinics around the world have different ways of assessing and treating children with gender dysphoria.

Children often rely on caregivers and health professionals to make treatment decisions on their behalf.

What this topic adds:

Children with gender dysphoria often experience a range of psychiatric comorbidities, with a high prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders, trauma, eating disorders and autism spectrum conditions, suicidality and self-harm.

It is vitally important to consider psychiatric comorbidities when prioritising and sequencing treatments for children with gender dysphoria.

The development of international treatment guidelines would provide greater consistency across diagnosis, treatment and ongoing management.

Introduction

Gender dysphoria is a psychological condition in which a person’s subjectively felt identity and gender are not congruent with their biological sex, often causing clinically significant impairment in social and other areas of functioning (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Smith & Matthews, Citation2015; De Vries et al., Citation2011). People experiencing gender dysphoria often describe themselves as being transgender, or gender non-binary, which is the sense that their personal identity and gender do not correspond with their birth sex. Several changes in how gender dysphoria is defined, previously referred to as gender identity disorder, have been made in the current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

For children diagnosed with gender dysphoria, the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria outline that the child’s subjective experience of their own gender is different to their birth sex. The child may insist they are the other gender or have a strong dislike for their sexual anatomy. In some cases, children have been known to mutilate their genitals to relieve their inner distress (Smith & Matthews, Citation2015). The World Health Organisation had also recently updated the diagnosis from gender identity disorder to “gender incongruence in childhood” in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (11th ed,; World Health Organization, Citation2020) using the same criterion for assessment and diagnosis as the DSM-5. Both updates suggest a global consensus that children with gender dysphoria are likely to experience profound psychological and physical difficulties, impacting negatively on their quality of life, mental wellbeing and capacity to integrate socially.

Children as young as two years old have been reported to present with symptoms of gender dysphoria (Cohen-Kettenis et al., Citation2002; Drummond et al., Citation2008). Some studies estimate 10% of children persist with the condition into adolescence and adulthood (Zucker, Citation2008), while later studies estimate between 12% and 27% of cases persist with the condition (Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2001; Drummond et al., Citation2008). The prevalence rates for gender dysphoria are generally collated across all age ranges; DSM-5 reports a conservative estimation of 0.01% of the natal male population and 0.003% of the natal female population experience gender incongruence (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

A range of studies finds gender dysphoria is becoming increasingly prevalent and this trend is particularly highlighted in child populations. Included in these increased referrals are children presenting at younger ages, with the median age now seeking assessment and treatment estimated to be 8 years old (M = 11, SD = 2.16) (De Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2012). The reason for the increase in referrals is largely unknown. Some studies report factors such as an increase in role models like gender non-conforming celebrities, as well as a greater visibility of the gender-diverse community in the media (Chen et al., Citation2016). With the increase in referrals to gender clinics, a growing interest in how children with gender dysphoria are being clinically treated and managed is also occurring across the world (Kruekels & Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2011).

Children have no legal ability to provide informed consent for medical treatment or to engage in decision-making about their condition. As such, children often rely on caregivers and health professionals to make treatment decisions on their behalf (Drescher et al., Citation2016). Parents may not always make the right decisions for their child and a bioethical argument exists as to whether parental authority should not encompass denying children with gender dysphoria access to medical treatments (Priest, Citation2019). Gender clinics around the world have different ways of assessing and treating children with gender dysphoria. Some clinics strongly disagree with any medical intervention prior to adulthood and instead focus on psychological treatment for both the family and the child (De Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, Citation2012). Other treatment models include a social role transition to the affirmed gender, which is seen as a reversible means of managing the child’s distress until it is known whether the gender dysphoria is persisting into adolescence (Steensma et al., Citation2013). Other clinics work exclusively in a medical model and facilitate the administration of puberty suppressing hormones in children as young as 8 years old, relying on medical intervention to treat the symptoms of gender dysphoria (Spack et al., Citation2012). An Australian standards of care and treatment guideline was released to maximise the quality of care provision for children with gender dysphoria, recommending a move away from treatment based on chronological age, with the timing of medical transition based on the patient’s capacity to make informed decisions, including consideration of the severity of psychiatric comorbidities when making clinical decisions about treatment (Telfer et al., Citation2018).

The core symptoms of gender dysphoria in childhood rarely exist in isolation; more commonly the symptoms are exacerbated by psychosocial stressors and psychiatric disorders (Vrouenraets et al., Citation2015). There are several psychiatric comorbidities in populations of children with gender dysphoria, such as autism spectrum conditions (VanderLaan et al., Citation2015), anxiety and depressive disorders (Holt et al., Citation2014), eating disorders (Russell & Keel, Citation2002), self-harm and suicidality (Reisner et al., Citation2015), psychosis and posttraumatic stress disorder (Coleman et al., Citation2012). Most of the studies on comorbidities are conducted in gender clinics, where there may be a stronger clinical emphasis on gender dysphoria as the core source of the child’s suffering (De Vries et al., Citation2011). While treating gender dysphoria as the primary condition is important, psychiatric comorbidities often have a greater likelihood of persisting into the child’s future and complicating mental health outcomes throughout the medical transition (Steensma et al., Citation2011). This suggests it is vitally important to consider psychiatric comorbidities when prioritising and sequencing treatments for children with gender dysphoria (De Vries et al., Citation2011).

The absence of a global and coordinated approach to treatment for children with gender dysphoria triggered the formation of an American Psychiatric Association Taskforce in 2012, to determine whether sufficient credible evidence existed to create broad, global treatment guidelines (Byne et al., Citation2012). A recommendation of the Taskforce was to prioritise the psychological wellbeing of the child when assessing for medical treatments, by diagnosing and providing treatment for any psychiatric comorbidities (Byne et al., Citation2012). Despite the Taskforce’s recommendations, there appear to be no randomised controlled treatment outcome studies on psychiatric comorbidities for children with gender dysphoria. This means the highest level of evidence available for treatment recommendations can best be characterised as expert opinion. These opinions vary widely about what appropriate treatment is, and these decisions are often influenced by a theoretical orientation, as well as assumptions and beliefs regarding the origins, meanings and perceived rigidity or malleability of gender identity (Drescher & Byne, Citation2012). The aim of this review was to identify the method utilized and appraise the methodological quality of studies of the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity among children presenting with gender dysphoria, including (1) was gender dysphoria diagnosed using DSM-5 criteria, (2) were psychiatric comorbidities diagnosed by a comprehensive psychological assessment, including the use of valid and reliable psychological tests, and 3) how psychiatric comorbidities are managed regarding treatment recommendations.

Method

Search strategy

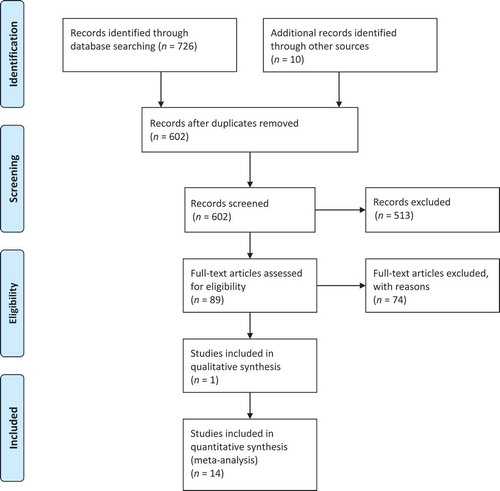

This systematic review adhered to the guidelines detailed in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement (Moher et al., Citation2009). A systematic literature search was conducted using the following search terms (“gender dysphoria” OR “gender identity”) AND (comorbid* OR psychopathology) AND psych* AND child*. The search was undertaken in Medline, PsychINFO, CINAHL, Scopus and Web of Science. The reference lists from the selected studies were also screened for additional relevant studies. A grey literature search was conducted using the University of Canberra database, a multidisciplinary database that contains research reports, conference papers and dissertations covering the social and biomedical sciences. Clinical trial registries were also searched to identify trials at various stages, from registration of the protocol to trial completion. Additional websites known to contain research were also searched, including the Australian Psychological Society website, Google Scholar and Research Gate.

Studies published between 1980 and 2019 were selected for inclusion in the review. The year of 1980 was chosen because gender dysphoria was formally recognised as a diagnosis in the DSM-III at this time. Non-clinical case studies and studies which were not published in English were excluded from the review. Studies with children and adolescents were included in the initial searching, to identify studies that included populations of children aged two to 12 years old. The lower bound of 2 years old was selected as this was found to be when children begin to develop social awareness of gender roles (Martinot et al., Citation2012). The upper bound of 12 years old was decided as a cut-off age by using the Tanner Scale (Hembree, Citation2012), a measure of physical development commonly used in studies of children with gender dysphoria to contribute to age-appropriate medical decision-making.

Some studies had participants older than 12 years and these studies were still included in the review, if they also had participants 12 years and under in the study. The studies had to include participants who met the DSM-5 diagnostic threshold for gender dysphoria. Studies which included participants with sub-threshold symptoms were excluded. It was anticipated that many studies were likely to be non-randomised (observational) and uncontrolled. It was decided to include these studies as they were relevant to the research question. Review articles, commentaries and letters were excluded Please refer to Appendix A for additional details on the Prisma flow diagram.

Procedure

Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were examined. In the first instance, 726 studies were identified using a database search and an additional 10 studies were found searching the internet. Duplicates (n = 134) were removed using the Endnote program. A review of the titles led to 513 records being excluded. The main reason for the exclusion of these records was the study titles did not include any reference to psychiatric comorbidities and gender dysphoria. The remaining 89 articles were screened by abstract. There were 74 articles excluded based on: (1) the population was not relevant (adults) or (2) the study did not have any participants (a literature review) or (3) the study used a projective test such as the Rorschach as a measure of distress. A spreadsheet was created to record the reasons for exclusion for each of the full-text articles reviewed. presents a Prisma flow diagram and summarises the systematic review of the 15 articles.

Assessment of quality and risk of bias

The study used a checklist based on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality appraisal checklist for quantitative studies (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2017). This checklist had been created and adapted from the Graphical Appraisal Tool for Epidemiological studies (GATE) developed by Jackson et al. (Citation2006) and revised for public health studies. The criteria used to assess the methodological quality of each study were: (1) how the population was selected, (2) whether a comprehensive psychological assessment was undertaken, (3) the duration and adequacy of study follow-up, (4) the proportion of participants lost to follow up, (5) whether there was blinding of key study personnel, (6) conflict of interest/funding disclosures, (7) whether gender dysphoria was diagnosed using DSM-5 criteria and (8) the age of the study.

While the risk of bias and the methodological quality of studies can be assessed using checklists or scales, these instruments often contain items or criteria that are not directly related to internal validity (Jüni et al., Citation2001; Moher et al., Citation2009). Therefore, this systematic review used a domain-based evaluation as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration, in which critical assessments were made separately for different domains, such as a selection or attrition bias (see Appendix B). The domain-based method was developed between 2005 and 2007 by a working group of methodologists and reviewers, who found this was an optimal approach as it was not based on a “generally accepted” criterion found in a checklist or scale (Lundh & Gøtzsche, Citation2008). The articles in this systematic review were coded using symbols to represent either a low risk of bias (++), medium risk of bias (+) or a high risk of bias (-) (see ). The process used to assess the methodological quality of the selected studies was also reviewed by two independent assessors at the University of Canberra as an additional reliability check.

Results

Participant characteristics

Five of the studies (33.3%) focussed on participants in the population of interest, children aged between two – 12 years old. A further five studies (33.3%) had participants with wider age ranges (between two – 20 years old). These studies contained a large number of participants in the 5 years and below age range, which is an important age range for children in terms of the onset and awareness of gender-linked behaviours (Martin et al., Citation2002). The remaining five studies (33.3%) had participants in the eight – 20 age range, meaning a third of the studies in the systematic review had a limited focus on the population of interest. Six of the studies were from the Netherlands (40.0%), six of the studies were from the United States (40.0%), one study (6.6%) was from Australia and one study (6.6%) was from the United Kingdom. The final study had a mix of participants from both Canada and the Netherlands (6.6%). Research from the Netherlands and the United States dominated the sample, with 12 of the 15 studies including data from either country. In terms of sample size, the range over the 15 studies varied between 39 and 2778 participants.

Study design and data collection method

Three of the studies (20.0%) used an experimental design (matched pairs and mixed factorial design, respectively) and one of these studies also included a quasi-experimental comparison between-groups, as well as a clinical case series. Ten studies (66.6%) were observational design, including cross-sectional (three studies), six clinical case series (one twin study) and one study (6.6%) was a longitudinal design. Two studies were quasi-experimental (13.3%), both using a between pre-existing groups design. All 15 of the studies included in the systematic review used convenience sampling as the method for obtaining participants. In terms of recruitment, 12 studies (80.0%) included children referred to a gender clinic. One of the studies (6.6%) recruited children through newspaper advertising, another study (6.6%) recruited from a National Longitudinal Study and the final study (6.6%) recruited participants from local schools.

The data on psychiatric comorbidity was collected using self-report measures in six studies (40.0%). Four studies (26.6%) used a combination of self-report measures and a clinical interview (with one of these studies including the collection of biodata, such as heart rate), three studies (20.0%) used a clinical interview only. Two studies (13.3%) reviewed clinical data only, such as patient files, including referral letters, clinical notes and reports. There was poor consistency across studies regarding declarations of conflicts of interest and funding disclosures. Seven studies (46.6%) did not state whether there were any conflicts of interest or whether funding was received for the study. Six of the studies (40.0%) did declare conflicts of interest and the receipt of funding. One study (6.6%) disclosed funding only, and one study (6.6%) disclosed a conflict of interest but did not mention funding.

Gender dysphoria and psychiatric comorbidity

In terms of the diagnosis of gender dysphoria, nine studies (60.0%) explicitly reported whether their participants were diagnosed with gender dysphoria using DSM-5 criterion. The remaining six studies (40.0%) mentioned that a clinical interview was conducted, without mentioning whether the participants met the DSM-5 criterion for gender dysphoria. In terms of psychaitric comorbidities, five studies (33.3%) measured internalising and externalising behaviours (mood, anxiety and aggression difficulties), five studies (33.3%) measured internalising and externalising behaviours as well as a range of other DSM-5 conditions, such as specific phobia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, tic disorder, psychosis, eating disorders, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Two of the studies (13.3%) focussed solely on ASD, one study (6.6%) measured separation anxiety and depression, and the final study (6.6%) assessed against all DSM-5 clinical disorders (not including personality disorders).

To measure psychiatric comorbidities, five studies (33.3%) used the Child Behaviour Check List (CBCL). A further three studies (20.0%) used the CBCL and additional tools such as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), Spielberger’s Trait Anger (STAI) and Spielberger’s Trait Anxiety (STAI). Two studies (13.3%) used no assessment tool, and the remaining four studies (26.6%) used only one assessment tool. The tool selected was not consistent across studies, ranges included the Coolidge Personality and Neuropsychiatric Inventory (CPNI), Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO-10), the DISC-IV or the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS). The final study (6.6%) used two assessment tools, the National Institute of Health Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS Scale) and the Harter Self Perception Scale. Most studies (80.0%) did not report the reliability coefficients of the selected assessment tools. However, the remaining studies did include these figures as an indicator of the robustness of the study. While the majority (60.0%) of studies used valid and reliable psychological tests, only four (26.6%) used a combination of clinical interview and psychological testing for clinical case formulation and diagnostic purposes.

Mental health outcomes were inconsistently operationalised across studies. For example, depression was assessed using a variety of tools, such as the CBCL which had scales orientated towards DSM-5 criterion, but it was not diagnostic for major depressive episode (Cohen-Kettenis et al., Citation2002). Other studies used the DISC-IV which is explicitly based on diagnostic level DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder (De Vries et al., Citation2011). Another study used the PROMIS Scale, which did not include the physiological aspects of depressive disorders, such as weight changes and sleep disturbance (Durwood et al., Citation2017). Many studies of mood disorders also used diverse clinical screening cut-off scores, such as “depressive distress in the last seven days” (de Vries et al., Citation2011; Durwood et al., Citation2017), “scores within a 90th percentile” (Cohen-Kettenis et al., Citation2002), a “clinical diagnosis of major depressive episode” (Holt et al., Citation2014; Spack et al., Citation2012) or “symptoms within the last 12 months” (De Vries et al., Citation2011). There were also differing timeframes for assessment, such as “lifetime prevalence”, “distress in the last seven days” and “within the last 12 months”. Some studies used heterogeneous sub-populations of people with gender dysphoria, such as “predominantly homosexual” (Zucker, Citation2002), “Caucasian races only” (Aitken et al., Citation2016), “social ranking” of the parents (for example, either “professionals” or “unskilled labourers”) (Cohen-Kettenis et al., Citation2002) or participants considered “eligible for puberty supressing hormones” (De Vries et al., Citation2011).

Despite these inconsistencies, data consistently showed that children with gender dysphoria were burdened by mental health concerns. For example, 21.0% of a sample of 105 children had an anxiety disorder (De Vries et al., Citation2011), 7.8% of a sample of 204 children were found to have co-occurring ASD and 44.3% of a sample of 97 children were found to have significant psychiatric history, including 9.3% of the sample had attempted suicide. It was commonly understood that children with gender dysphoria often suffered from comorbidities that worsened during puberty, at which time they were generally at high risk of suicide (Lopez et al., Citation2016).

In terms of how psychiatric comorbidities were managed, six studies (40.0%) discussed the importance of referrals for support. One of these studies recommended that patients with comorbid ASD should be referred to a specialist clinic for assessment and treatment. Four of the studies (26.6%) recommended that referrals for the treatment of serious psychiatric comorbidities (for example, major depressive episode) should be actioned prior to treating gender dysphoria. One study (6.6%) discussed the importance of children having access to a mental health professional, but it was unclear whether this was for treatment of psychiatric comorbidities or for support through the process of medical transition of gender. Only one study (6.6%) explicitly stated referrals for treatment of psychiatric comorbidities were actioned.

Methodological quality and risk of bias

The risk of bias was assessed using guidance contained in the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias in studies (“Cochrane Handbook,” Citation2017). Seven studies (46.6%) were classified as having a high risk of bias (-), a further seven studies (46.6%) were classified as having a medium risk of bias (+) and one study (6.6%) was classified as having a low risk of bias (++). This final study was an experimental design which used the participants as their own controls. Fourteen of the 15 studies were assessed as having a medium to high risk of bias. All studies used convenience sampling. The data collected in five studies were up to 44 years old (33.3%), four studies (26.6%) had high rates of participant exclusion and no studies used blinding of key study personnel. Overall, the methodological quality of the studies was poor.

Discussion

This was the first systematic review of studies on the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity among children presenting with gender dysphoria. The aim of the study was to assess the methodological quality of the studies (including risk of bias) and to investigate whether (1) gender dysphoria was diagnosed using DSM-5 criteria, (2) ascertain how psychiatric comorbidities were diagnosed (3) how psychiatric comorbidities were managed in terms of actioning referrals for treatment.

Methodological quality

Overall, the methodological quality of the existing data was poor which indicated a potential systematic bias in the literature on this topic area. Of the 15 studies reviewed, 14 were classified as either a medium or high risk of bias. Over half of the studies used a clinical case series design, which provided a retrospective look at a series of cases with features in common. This design can be suited to the study of rare or new psychiatric phenomenon, but it may not be of value for studies on psychiatric comorbidities in children with symptoms of gender dypshoria (Vandenbroucke, Citation2001) as many children around the world are already receiving medical treatment. It was a suitable research design for older studies undertaken when gender dysphoria was first included in DSM-III in the 1980s. However, it appeared the study designs in this topic area had not yet progressed to testing hypotheses, as no study used a fully blinded, randomised controlled trial design. In the hierarchy of research designs, the results of randomised, controlled trials were generally considered to be evidence of the highest grade, whereas observational studies were viewed as having less validity because they often overestimated treatment effects (Concato et al., Citation2000). This suggests the results of global studies may have very different explanations and recommendations regarding psychiatric comorbidities among children with gender dysphoria simply because of the limitations of the study designs (Costa & Colizzi, Citation2016).

All studies gathered their data using convenience, or non-probability sampling. Most of the studies used data from participants referred to a gender clinic. The assumption with this type of sampling was that the members of the target group were homogeneous (Etikan et al., Citation2016), suggesting there would be no difference in the research results obtained with a random sampling method. While this means of sampling is often affordable and convenient for the researcher (Heckathorn, Citation2011), none of the studies described how their samples differed from a sample that would be randomly selected. This represented a critical limitation in terms of not being able to generalise the study results to the broader population of children with gender dysphoria.

Another factor which limited the generalisability was the data being dominated by studies from the United States and the Netherlands, with over half of the studies not declaring who funded it or whether there was a conflict of interest. This raises concerns about whether the participants’ welfare was unduly influenced by a secondary interest, such as financial gains for the clinics or the desire for professional recognition by researchers (Bekelman et al., Citation2003). It was likely that Western countries conducted most of the studies in this topic area as their attitudes were progressive, in terms of concern for the welfare of people with gender dysphoria and a desire to reduce stigma and discrimination (Vance Jr et al., Citation2010). However, it was difficult to make this inference as funding and conflicts of interest were often not declared.

Clinical implications

Children with gender dysphoria often report a reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety after receiving gender-affirming medical treatments, but they do not always show improvements in symptoms of gender dysphoria (Chew et al., Citation2018). The lack of follow-up and referrals for treatment of psychiatric comorbidities in the reviewed studies was concerning, given there may be psychological symptoms related to having gender dypshoria which are assumed to be treated once medical interventions are pursued.

Furthermore, the studies examined in the review did not make mention that previous twin studies had found a biological basis to gender dysphoria involving endocrine, neurobiological and genetic factors. For instance, an increased prevalence of gender dysphoria was observed among people who experienced atypical prenatal androgen exposure in utero, such as females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (Fisher et al., Citation2016). Heritability studies also suggested a genetic component: 23% to 33% of monozygotic twin pairs were concordant for gender dysphoria (Diamond, Citation2013). While genetics may play a role in the development of gender dysphoria in children, it was not found to be the sole determinant which means that psychiatric comorbidities may also impact in some way on the development and course of gender dysphoria.

Limitations and strengths

The main strength of this paper was its focus as the first systematic review to summarise and critically assess the prevalence data on psychiatric comorbidities of children with gender dysphoria. The studies did not appear to have become methodologically stronger over the years, noting the paucity of randomised controlled trials available. The majority of studies were conducted in Western countries and the results may have been influced by the level of tolerance in society, the healthcare system, legislation regarding the rights of people with gender dysphoria and academic interest (Arcelus et al., Citation2015). The paucity of studies on children with gender dysphoria in developing countries may indicate an absence of clinical services, which would be likely to perpetuate psychiatric comorbidities (Claes et al., Citation2015). The study was also limited by the high heterogeneity of studies, noting the clear differences in the methodology of the studies included in the review.

Future research

Further research is needed in a few key areas. First, longitudinal data on the factors that may predict children who continue to present with symptoms of gender dysphoria into adolescence, versus those who do not (Steensma et al., Citation2011) may improve knowledge on whether psychiatric comorbidities mediate this relationship. Gender affirming hormone treatment often improves mental health outcomes but it does not always improve body image problems or symptoms of gender dysphoria (Chew et al., Citation2018), indicating further work may be important in terms of evaluating the efficacy of medical treatment for symptoms of gender dysphoria.

Qualitative studies on the experiences of children with gender dysphoria may also provide valuable information on the potential relationship between internalised transphobia and the development of psychiatric comorbidities. Furthermore, randomised controlled trials on the effectiveness of psychological intervention for complex psychiatric comorbidities, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, ASD and eating disorders are required, specifically how treatment of these conditions may relate to improved coping with gender dysphoria into adolescence. Studies into the relationship between gender dysphoria and mentalising ability for those with autism spectrum conditions may also be of value, to determine whether theory of mind deficits affect perceptions of gender identity.

Conclusion

The results of the study found that children with gender dysphoria often experience a range of psychiatric comorbidities, with a high prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders, trauma, eating disorders and autism spectrum conditions, suicidality and self-harm. Most importantly, this systematic review found that there was no standardised approach to the assessment, diagnosis, treatment and clinical management of children with gender dysphoria and psychiatric comorbidities, including a paucity of randomised control trials, which has implications clinical decision-making.

Noting children do not have capacity to consent to their own medical treatment, it was concerning to find that there were a range of different treatment models used around the world for children presenting with gender dypshoria, from early intervention medical treatments involving parental consent for treatment, to denial of medical treatment for children and adolescents. This may have implications for the level of psychological support that a child may receive depending on how the respective treatments for gender dysphoria are perceived. There was also an absence of studies from developing countries on gender dypshoria in childhood, suggesting implications may arise for the assessment and treatment of psychiatric comorbidities in non-gender clinics. Looking ahead, it will be essential for future researchers to expand on the findings of existing studies by using large, prospective longitudinal studies with sufficient follow-up, statistical power and the inclusion of well-matched controls.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aitken, M., VanderLaan, D. P., Wasserman, L., Stojanovski, S., & Zucker, K. J. (2016). Self-harm and suicidality in children referred for gender dysphoria. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(6), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.001

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

- Arcelus, J., Bouman, W. P., Van den Noortgate, W., Claes, L., Witcomb, G., & Fernandez-Aranda, F. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies in transsexualism. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 807–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j3europsy.2015.04.005

- Bekelman, J. E., Li, Y., & Gross, C. P. (2003). Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: A systematic review. Jama, 289(4), 454–465. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.4.454

- Byne, W., Bradley, S. J., Coleman, E., Eyler, A. E., Green, R., Menvielle, E. J., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F., Pleak, R. R., & Tompkins, D. A. (2012). Report of the American Psychiatric Association task force on treatment of gender identity disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(4), 759–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9975-x

- Chen, M., Fuqua, J., & Eugster, E. A. (2016). Characteristics of referrals for gender dysphoria over a 13-year period. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(3), 369–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.010

- Chew, D., Anderson, J., Williams, K., May, T., & Pang, K. (2018). Hormonal treatment in young people with gender dypshoria: A systematic review. Paediatrics, 141(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3742

- Claes, L., Bouman, W. P., Witcomb, G., Thurston, M., Fernandez‐Aranda, F., & Arcelus, J. (2015). Non‐suicidal self‐injury in, trans people: Associations with psychological symptoms, victimization, interpersonal functioning, and perceived social support. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(1), 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12711

- Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. (2017). The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/

- Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2001). Gender identity disorder in DSM? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(4), 391. 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00006

- Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Owen, A., Kaijser, V., Bradley, S. J., & Zucker, K. J. (2002). Demographic characteristics, social competence and behaviour problems in children with gender identity disorder: A cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/pp707-jacp-457106

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., & Monstrey, S. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

- Concato, J., Shah, N., & Horwitz, R. I. (2000). Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(25), 1887–1892. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM2000006223422507

- Coolidge, F. L., Thede, L. L., & Young, S. E. (2002). The heritability of gender identity disorder in a child and adolescent twin sample. Behavior Genetics, 32(4), 251–257. 10.1023/A:1019724712983

- Costa, R., & Colizzi, M. (2016). The effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on gender dysphoria individuals’ mental health: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12(12), 1953–1966. 10.2147/NDT.S95310

- De Vries, A. L. C., Noens, I. L. J., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. et al. (2010). Autism spectrum disorders in gender dysphoric children and adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 930–936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0935–9

- De Vries, A. L., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2012). Clinical management of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents: The Dutch approach. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(3), 301–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.653300

- De Vries, A. L., Steensma, T. D., Doreleijers, T. A., & Cohen‐Kettenis, P. T. (2011). Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity isorder: A prospective follow‐up study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(8), 2276–2283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01943.x

- Diamond, M. (2013). Transsexuality among twins: Identity concordance, transition, rearing and orientation. International Journal of Transgenderism, 14(1), 24–38. 10.1080/15532739.2013.750222

- Drescher, J., & Byne, W. (2012). Gender dysphoric/gender variant (GD/GV) children and adolescents: Summarizing what we know and what we have yet to learn. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(3), 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.653317

- Drescher, J., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Reed, G. M. (2016). Gender incongruence of childhood in the ICD-11: Controversies, proposal and rationale. The Lancet, 3(47), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00586-6

- Drummond, K. D., Bradley, S. J., Peterson-Badali, M., & Zucker, K. J. (2008). A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 34–45. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.34

- Durwood, L., McLaughlin, K. A., & Olson, K. R. (2017). Mental health and self-worth in socially transitioned transgender youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(2), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.10.016

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Fisher, A. D., Ristori, J., Fanni, E., Castellini, G., Forti, G., & Maggi, M. (2016). Gender identity, gender assignment and reassignment in individuals with disorders of sex development: A major dilemma. Journal of Endocrinology, 39(11), 1207–1224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-016-0482-0

- Heckathorn, D. D. (2011). Snowball versus respondent‐driven sampling. Sociological Methodology, 41(1), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9531.2011.01244.x

- Hembree, W. C. (2012). Guidelines for pubertal suspension and gender reassignment for transgender adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 20(4), 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2011.08.004

- Hewitt, J. K., Paul, C., Kasiannan, P., Grover, S. R., Newman, L. K., & Warne, G. L. (2012). Hormone treatment of gender identity disorder in a cohort of children and adolescents. Medical Journal of Australia, 196(9), 578. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja12.10222

- Holt, V., Skagerberg, E., & Dunsford, M. (2014). Young people with features of gender dysphoria: Demographics and associated difficulties. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 21(1), 1–14. published online. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104514558431

- Jackson, R., Ameratunga, S., Broad, J., Connor, J., Lethaby, A., Robb, G., Wells, S., Glasziou, P., & Heneghan, C. (2006). The GATE frame: Critical appraisal with pictures. ACP Journal Club, 144(2), A8–A8. https://doi.org/10.7326/ACPJC-2006-144-2-A08

- Jüni, P., Altman, D. G., & Egger, M. (2001). Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 323(7303), 42. 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42

- Kruekels, B. P., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2011). Puberty suppression in gender identity disorder: The Amsterdam experience. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 7(8), 466–472. 10.1038/nrendo.2011.78

- Lopez, X., Stewart, S., & Jacobson-Dickman, E. (2016). Approach to children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Pediatrics in Review, 37(3), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2015-0032

- Lundh, A., & Gøtzsche, P. C. (2008). Recommendations by Cochrane Review Groups for assessment of the risk of bias in studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-22

- Martin, C. L., Ruble, D. N., & Szkrybalo, J. (2002). Cognitive theories of early gender development. Psychological Bulletin, 128(6), 903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.903

- Martinot, D., Bagès, C., & Désert, M. (2012). French children’s awareness of gender stereotypes about mathematics and reading: When girls improve their reputation in math. Sex Roles, 66(3–4), 210–219. 10.1007/s11199-011-0032-3

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2017). Appendix F: Quality appraisal checklist for quantitative intervention studies. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-f-quality-appraisal-checklist-quantitative-intervention-studies

- Priest, M. (2019). Transgender children and the right to transition: Medical ethics when parents mean well but cause harm. American Journal of Bioethics, 19(2), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2018.1557276

- Reisner, S. L., Vetters, R., Leclerc, M., Zaslow, S., Wolfrum, S., Shumer, D., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2015). Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health centre: A matched retrospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(3), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264

- Russell, C. J., & Keel, P. K. (2002). Homosexuality as a specific risk factor for eating disorders in men. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31(3), 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10036

- Shumer, D. E., Reisner, S. L., Edwards-Leeper, L., & Tishelman, A. (2016). Evaluation of Asperger syndrome in youth presenting to a gender dysphoria clinic. LGBT Health, 3(5), 387–90. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2015.0070

- Smith, M. K., & Matthews, B. (2015). Treatment for gender dysphoria in children: The new legal, ethical and clinical landscape. Medical Journal of Australia, 202(2), 102–106. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja14.00624

- Spack, N. P., Edwards-Leeper, L., Feldman, H. A., Leibowitz, S., Mandel, F., Diamond, D. A., & Vance, S. R. (2012). Children and adolescents with gender identity disorder referred to a pediatric medical centre. American Academy of Pediatrics. published online February 20, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0907

- Spack, N. P., & Leibowitz, S. F. (2011). The development of a gender identity psychosocial clinic: Treatment issues, logistical considerations, interdisciplinary cooperation, and future initiatives. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20(4), 701–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2011.07.004

- Steensma, T. D., Biemond, R., De Boer, F., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2011). Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: A qualitative follow-up study. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 16(4), 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104510378303

- Steensma, T. D., McGuire, J. K., Kreukels, B. P., Beekman, A. J., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2013). Factors associated with desistence and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: A quantitative follow-up study. Journal American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(6), 582–590. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.016

- Telfer, M., Tollit, M. A., Pace, C. C., & Pang, K. (2018). Australian standards of care and treatment guidelines for transgender and gender diverse children and adolescents. Medical Journal of Australia, 209(3), 132–136. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.01044

- Vance Jr, S. R., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Drescher, J., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F., Pfäfflin, F., & Zucker, K. J. (2010). Opinions about the DSM gender identity disorder diagnosis: Results from an international survey administered to organizations concerned with the welfare of transgender people. International Journal of Transgenderism, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532731003749087

- Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2001). In defence of case reports and case series. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134(4), 330–334. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003–4819-134-4-200102200-00017

- VanderLaan, D. P., Postema, L., Wood, H., Singh, D., Fantus, S., Hyun, J., Leef, J., Bradley, S. J., & Zucker, K. J. (2015). Do children with gender dysphoria have intense/obsessional interests? Journal of Sexual Research, 52(2), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.860073

- Vrouenraets, L., Fredriks, A. M., Hannema, S. E., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & De Vries, M. C. (2015). Early medical treatment of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: An empirical ethical study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(4), 1–7. published online. https://doi.org/10.1066/j.jadohealth.2015.04.004

- Wallien, M. S., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2008). Psychosexual outcome of gender-dysphoric children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(12), 1413–1423. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31818956b9

- Wallien, M. S., Swaab, H., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2007). Psychiatric comorbidity among children with gender identity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(10), 1307–1314. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.obo13e3181373848

- Wallien, M. S., Van Goozen, S. H., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2007). Physiological correlates of anxiety in children with gender identity disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 16(5), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-007-0602-7

- World Health Organization. (2020). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- Zucker, K. J. (2008). Children with gender identity disorder: Is there a best practice? Neuropsychiatrie De L’enfance Et De L’adolescence, 56(6), 358–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurenf.2008.06.003

- Zucker, K. J. (2002). Gender identity disorder. In Rutter, M. &Taylor, E. A. (Eds). Child and adolescent psychiatry: modern approaches. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-86542-880–8.

Appendix A

Table A1. Summary of studies

Appendix B

Table B1. Methodological quality of studies