ABSTRACT

Objective

Emergency service workers (i.e., police, fire, ambulance, rescue personnel) are exposed to stressful events that can adversely impact their mental health and well-being. This systematic review investigated (1) what well-being initiatives and interventions have been implemented with Australian and New Zealand emergency service workers, (2) how they have been evaluated, and (3) whether they were effective.

Methods

A systematic literature search identified 19 peer-reviewed studies eligible for inclusion.

Results

Eleven studies examined secondary interventions, seven examined primary interventions and only one study examined a tertiary intervention. Most studies measured mental health outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety). However, some studies used evaluation measures that were not directly related to mental health or well-being (e.g., satisfaction, changes to attitudes). Interventions including physical activity, manager mental health training, social support, psychological debriefing, mindfulness, and an ambulance chaplaincy initiative were found to lead to improvements in mental health and well-being in Australian and New Zealand emergency service workers. Only two ongoing and self-sustaining mental health initiatives were reported.

Conclusions

Further research is required into primary interventions and organisational-level initiatives to enable a preventative approach to mitigate daily stress and enhance the mental and physical well-being of emergency workers.

Key Points

What is already known about this topic:

Emergency service workers have higher rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression than the general population.

Evidence based mental health and well-being support is crucial for emergency service workers to ensure they can protect their respective communities effectively.

Research focused on the prevalence of mental health issues for emergency workers is well represented in the literature, however, evidence for interventions designed to improve mental health outcomes is scarce.

What this topic adds:

This review contributes by identifying and evaluating studies focused on mental health and well-being interventions for emergency service workers in Australia and New Zealand.

This review distinguished between interventions (programs with defined start and end points) and initiatives (programs that are ongoing and self-sustaining), and only two initiatives were reported.

Interventions that led to improvements in mental health and well-being were those related to mindfulness, physical activity, manager mental health training, social support, psychological debriefing, and an ambulance chaplaincy initiative.

Emergency service workers, including police, fire, ambulance, and rescue personnel, provide an essential service to the Australian and New Zealand community by responding to a wide variety of emergency situations and accidents (Barratt et al., Citation2018; Harvey et al., Citation2017). They often work in high-pressure situations, supporting people in urgent need of help, while putting their own safety at risk (Barratt et al., Citation2018). They work long and irregular hours while also being expected to be on stand-by, ready to respond to any emergency that arises twenty-four hours per day (Barratt et al., Citation2018; Lawrence et al., Citation2018). Even when not on the front line, emergency workers are indirectly exposed to potentially traumatising conditions such as taking witness statements from victims of abuse or identifying bodies in the aftermath of accidents or natural disasters (Lawrence et al., Citation2018). These factors, combined with fatigue and the physically demanding nature of the work, can make recovery from trauma difficult (Lawn et al., Citation2020). To rectify this, emergency service organisations have implemented a range of strategies to assist personnel in their recovery (Fogarty et al., Citation2021; LaMontagne et al., Citation2021). However, workers are less likely to seek help because of the stigma associated with mental health that is ingrained in the culture of emergency service workplaces (Lawn et al., Citation2020; Mackinnon et al., Citation2020). With almost 100,000 emergency service workers across Australia and New Zealand, it is crucial they receive adequate support to minimise mental health issues and ensure they can continue to protect their respective communities effectively (Fire and Emergency New Zealand, Citation2019; Harvey et al., Citation2017; New Zealand Police, Citation2021; St John Ambulance, Citationn.d.).

There are several geographical, institutional, and cultural characteristics that make the experience of emergency service workers in Australia and New Zealand unique. The geography of the region provides unique challenges for emergency workers such as substantial distances between towns and the prevalence of small remote areas that are difficult to access. For example, the Queensland Police Service operates within a land and coastal area nearly seven times larger than Britain (Bronitt & Finnane, Citation2012). Often small stations in regional and remote areas do not have the same access to resources that metropolitan areas have, thereby increasing the stress for responders and reducing their support (Barratt et al., Citation2018). New challenges are emerging, such as fire and rescue staff who are facing longer, more intense fire seasons (CSIRO, Citation2021) and more severe flooding as a result of climate change (CSIRO, Citation2020). Differences across geographies may impact the adoption and implementation of well-being interventions and initiatives, including different operating structures and jurisdictions. For example, Australian Police Services are centralised with state-wide jurisdictions while law enforcement in the United States is based around municipalities (Bronitt & Finnane, Citation2012). Australia and California have similar climates, plants, and worsening wildfires, however response operations and capabilities differ with California holding more machines, equipment, and aircrafts than Australia where Government and citizens work together through an extensive network of volunteers and community education (Cart, Citation2019). Considering the critical role emergency services play, measures to safeguard the mental and physical well-being of this workforce are of paramount importance.

The aim of this systematic review is to examine interventions and initiatives to improve the health and well-being of Australian and New Zealand emergency personnel. Workplace interventions can be classified across three levels as outlined by Tetrick and Quick (Citation2011). Primary interventions aim to prevent the onset of mental health issues and are delivered at the organisational level to all employees. Secondary interventions target groups of employees who are showing early signs of mental health issues or who are deemed at risk due to factors such as exposure to trauma. Tertiary interventions target individuals and aim to treat mental health issues by reducing their impact and severity (Tetrick & Quick, Citation2011). In this paper, we define interventions as activities that have time limits and defined start and end points and initiatives as activities that are ongoing and self-sustaining.

Presentation of mental health issues in emergency service workers

Research has shown that emergency service workers have higher rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression (Courtney et al., Citation2010; Lawson et al., Citation2012) and suicidal ideation than adults in the general population (Lawrence et al., Citation2018; Kyron et al., Citation2021). In 2018, Beyond Blue conducted an independent national survey exploring the mental health and well-being of 21,014 Australian emergency service personnel (Lawrence et al., Citation2018). They found that more than half of emergency service workers reported experiencing a traumatic event at work that severely affected them. They also found that one in three emergency service workers experienced high or extreme psychological distress, and 39% reported receiving a mental health diagnosis. Finally, they found that many emergency service personnel reported harmful alcohol consumption and poor sleep quality. Research also indicates that fatigue and burnout leads to poorer safety behaviour such as use of personal protective equipment and adherence to safe work practices (e.g., Smith et al., Citation2018). Fatigue and burnout can also diminish driving ability, decision-making, and concentration, and increase errors in drug administration for paramedics (Pyper & Paterson, Citation2016; Sofianopoulos et al., Citation2011). As such, there is a pressing need to determine effective strategies to reduce these impacts for emergency service workers.

Mental health interventions for emergency workers

The need for evidence-based interventions was highlighted in an Australian inquiry into the government’s role in addressing the mental health conditions of emergency workers. A report by the Black Dog Institute (Citation2018) cited instances where mental health interventions had been implemented at scale despite inadequate evidence to justify their effectiveness. A key example is the use of psychological debriefings following critical incidents that have been embedded in emergency service organisations. This is despite a systematic Cochrane review conducted by Rose et al. (Citation2003) that found that in a majority of studies single-session psychological debriefings did not prevent the onset of mental health issues, and in some instances, led to poorer outcomes. Furthermore, a review by Devilly et al. (Citation2006) reported instances where psychological debriefings were associated with an increased likelihood of developing PTSD. These findings highlight the need for emergency service organisations to implement interventions that have been evaluated and shown to be effective (Lawrence et al., Citation2018).

Research has identified several factors protective of mental health in this population including social support (Shakespeare-Finch et al., Citation2015; Skeffington et al., Citation2017), resilience (Gayton & Lovell, Citation2012; Kyron et al., Citation2021), mindfulness (Smith et al., Citation2011), sleep quality (Lawrence et al., Citation2018), coping strategies (Balmer et al., Citation2014; Kirby et al., Citation2011) and physical activity (McKeon et al., Citation2021). Additionally, interventions that seek to improve managerial support, mental health stigma, workplace culture, and mental health literacy may be beneficial (Lawrence et al., Citation2018; Lawn et al., Citation2020; Mackinnon et al., Citation2020; Petrie et al., Citation2018). Despite the evidence demonstrating the positive effect of such protective factors and interventions, some emergency workers are reluctant to seek help for reasons such as perceived stigma and concern that doing so would negatively impact their career (Barratt et al., Citation2018; Lawrence et al., Citation2018). Other barriers to help seeking include poor managerial response and inadequate services with limited access (Lawrence et al., Citation2018; Lawn et al., Citation2020; Mackinnon et al., Citation2020).

While we did not identify any published reviews evaluating well-being interventions with emergency service workers in Australia and New Zealand, several systematic reviews have examined emergency service worker well-being. First, Varker et al. (Citation2018) investigated research into the mental health and well-being of Australian emergency service workers and reviewed 43 studies conducted in the previous five years. They found that while there has been extensive research into organisational, social, and individual predictors of health and well-being, research on interventions to improve mental health and well-being outcomes was lacking. Furthermore, while they provided an overview of research activity, they did not evaluate study designs or research findings. Second, from an international perspective, Wild et al. (Citation2020) conducted a systematic review of studies using randomised and quasi-randomised designs that evaluated interventions designed to improve mental health and well-being for first responders in developed countries. Of the 13 eligible studies that they identified, six reported significant improvements in well-being, resilience, or stress management. They also found that the frequency and number of intervention sessions was an important factor for efficacy, reporting that interventions with a higher number and frequency of sessions produced greater improvements. However, the quality of studies varied and despite social support being established as critical for the mental health of emergency workers, the search strategy did not target social support interventions. Finally, Alden et al. (Citation2020) conducted a systematic review of psychological interventions for first responders across multiple geographies that targeted PTSD and acute stress disorder. However, they did not focus on interventions that can be used to prevent the onset of mental health disorders in these populations.

Overall, there is a broad body of literature focused on the prevalence of mental health issues for emergency workers in Australia and New Zealand (e.g., Varker et al., Citation2018); however, there is a paucity of evidence for interventions designed to improve mental health outcomes. There is also a gap in relation to examining the role of social support-based interventions in improving mental health outcomes. The research to date indicates that interventions delivered with a higher frequency over time are more effective than one-off or limited time-based interventions. However, it is unclear the extent to which there are evidence-based mental health initiatives that are ongoing and self-sustaining compared to interventions with imposed time limits and defined start and end points.

The current study

The current systematic review examined the scientific literature to assess (1) what mental health and well-being interventions and initiatives have been implemented with Australian and New Zealand emergency service workers, (2) how they have been evaluated, and (3) whether they have been effective.

Method

Procedure

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in line with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (Higgins et al., Citation2021) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA; Moher et al., Citation2009) guidelines. A review protocol was registered with Open Science Framework on 20 May 2021 (https://osf.io/pwsc6).

Search strategy

The search strategy used keywords related to population (e.g., police, firefighters), intervention/initiative (e.g., stress management, social support) and geographical location (e.g., Australia, New Zealand). These terms were combined with Boolean operators to search titles and abstracts. These keywords were also combined with database specific Subject Headings (e.g., MeSH in Medline). For a complete list of search terms please refer to the supplementary information document. The search strategy was executed on 26 February 2022 in Medline Complete, Embase, PsycInfo, and Business Source Complete, with no limit on publication date. For key studies, the research team hand searched reference lists and used Scopus to find citing articles.

Study selection

Articles were included if they were conducted in Australia or New Zealand, with first responder or emergency service populations (i.e., firefighters, police, emergency department workers, or ambulance personnel), had full-text articles available and included some type of psychological intervention or initiative (e.g., well-being, resilience, stress management, social support, etc.). Articles were excluded if they were not peer-reviewed, if they were a narrative literature review or not published in English.

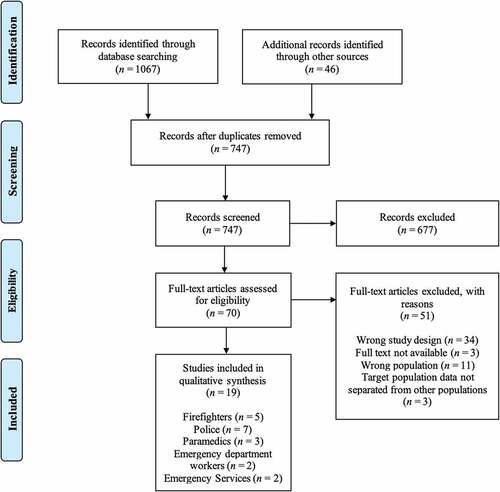

Articles from all databases were imported into EndNote X9 (The EndNote Team, Citation2013) and duplicate records were removed. Articles were then screened for inclusion using Covidence (Citation2014). Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria. Full-text articles were then independently reviewed by the same two reviewers. Throughout, disagreements were resolved through discussion with the broader research team. Additional citations were identified through snowball searching, reviewing reference lists, and systematic review articles. Corresponding authors were contacted for any articles where results for the target population were not separated from other populations.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Key details of the included studies were extracted into a template designed specifically for this investigation, outlining the author, year of publication, research aim, study design, participant information, intervention/initiative, and summary of findings. The first author completed the data extraction for studies focused on police, paramedic, and emergency department populations and the second author extracted data for firefighters and studies with multiple emergency service populations. The first and second authors then cross-checked the data.

The National Institute of Health (NIH, Citation2014) Quality Assessment Tools were utilised to assess methodological quality of the studies. Due to the range of study designs present in the included articles, the NIH Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies Tool and Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies Tool were used and matched to study design. Both tools contained 14-items examining the study design and reporting quality of the study, requiring a yes, no, not reported (NR), cannot determine (CD) or not applicable (NA) response to produce an overall rating of good (n = 9), fair (n = 6) or poor (n = 4). Please refer to the supplementary information document for a summary of the quality rating per study. Quality assessment was completed independently by two reviewers with discrepancies resolved through discussion to reach consensus.

Results

The initial search across all databases resulted in 1,067 articles, with an additional 46 articles identified through other sources. After the removal of duplicate records, the title and abstract of 747 articles were screened and 70 full-text articles were reviewed, of which, 19 met the eligibility criteria. Of the 19 studies, only one was conducted with a New Zealand population. One intervention was evaluated qualitatively and quantitatively across two separate studies (Xu et al., Citation2021, Citation2021). See for the PRISMA flow diagram outlining the number of studies excluded at each stage of the screening process.

presents information about the 19 studies including author, year of publication, research aim, study design, participation information, intervention/initiative, summary of findings, and a quality assessment of the articles. Findings were then synthesised based on study design and to assess the primary research questions of what interventions were conducted, how interventions were evaluated, and whether the interventions were effective.

Table 1. Background information, study design, participants, type of intervention and summary of findings.

Study characteristics

Articles were published from 1993 onwards, with 10 studies conducted in the last five years (from 2016 to 2021). Samples ranged in size from 12 to 806. Consistent with the demographics of the workforce, participants in most samples were predominantly male. There were seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Joyce et al., Citation2019; LaMontagne et al., Citation2021; Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017; Shochet et al., Citation2011; Skeffington et al., Citation2016; Tuckey & Scott, Citation2014; Xu et al., Citation2021), six quasi-experimental studies (Addis & Stephens, Citation2008; Ireland et al., Citation2007; Leonard & Alison, Citation1999; Lewis et al., Citation2013; Pinks et al., Citation2021; Robinson & Mitchell, Citation1993), four qualitative designs (Fogarty et al., Citation2021; Muller et al., Citation2009; Tunks Leach et al., Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2021), one interrupted time series (McKeon et al., Citation2021) and one mixed-methods design (Shakespeare-Finch & Scully, Citation2004). Applying our quality assessment, nine studies were assessed as good, six as fair, and four as poor. The studies were conducted with police officers (n = 7), firefighters (n = 5), ambulance personnel (n = 2), emergency department workers (n = 2), paramedic students (n = 1) and multi-emergency service populations (n = 2).

Types of interventions and initatives

There was substantial variation in the types of interventions and initiatives, of the 18 interventions or initiatives, seven were primary, ten were secondary, and one was a tertiary intervention. Five studies examined debriefing or employee assistance programs (Addis & Stephens, Citation2008; Leonard & Alison, Citation1999; Robinson & Mitchell, Citation1993; Shakespeare-Finch & Scully, Citation2004; Tuckey & Scott, Citation2014), four studies examined mental health literacy programs (Fogarty et al., Citation2021; LaMontagne et al., Citation2021; Lewis et al., Citation2013; Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017), two studies examined a program building resilience (Shochet et al., Citation2011; Skeffington et al., Citation2016), three studies focused on mindfulness (Joyce et al., Citation2019; Xu et al., Citation2021, Citation2021), and the remaining studies examined training supportive leadership behaviours (Muller et al., Citation2009), social support meetings (Pinks et al., Citation2021), chaplain services (Tunks Leach et al., Citation2021), a physical activity program (McKeon et al., Citation2021) and emotional disclosure in writing (Ireland et al., Citation2007).

Of the 19 studies included in this review, 17 were classified as interventions (time-limited) and two as initiatives (ongoing, self-sustaining). The structure, duration, and format of the interventions and initiatives varied. Nine interventions involved a debrief or face-to-face training session, each of varying lengths (Addis & Stephens, Citation2008; Fogarty et al., Citation2021; LaMontagne et al., Citation2021; Leonard & Alison, Citation1999; Lewis et al., Citation2013; Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017; Muller et al., Citation2009; Robinson & Mitchell, Citation1993; Tuckey & Scott, Citation2014). One intervention involved getting workers to write about their emotions for 15 minutes per day over four consecutive work shifts (Ireland et al., Citation2007). Eight interventions spanned multiple weeks. One involved four one-hour weekly sessions (Skeffington et al., Citation2016), another, seven two-hour weekly sessions, with two refresher sessions at various points up to 18-months post-intervention (Shochet et al., Citation2011), two were delivered online over six to ten weeks (Joyce et al., Citation2019; McKeon et al., Citation2021), one intervention involved the use of a smartphone application to guide mindfulness sessions over four weeks (Xu et al., Citation2021, Citation2021) and one involved an initial workshop followed by 12 weekly meetings (Pinks et al., Citation2021). The two studies classified as initiatives, evaluated ambulance chaplains (Tunks Leach et al., Citation2021), and employee assistance programs and peer support officers (Shakespeare-Finch & Scully, Citation2004), all of which are ongoing programs. There was only one study that considered long term effects, measuring outcomes of the intervention five years later (Addis & Stephens, Citation2008).

Evaluation methods and measures

The studies used a range of different outcome measures to evaluate the interventions. Eight studies assessed mental health outcomes, including psychological distress, PTSD symptoms, anxiety, stress, depression, burnout, well-being, and anger (Addis & Stephens, Citation2008; Ireland et al., Citation2007; Leonard & Alison, Citation1999; McKeon et al., Citation2021; Pinks et al., Citation2021; Skeffington et al., Citation2016; Tuckey & Scott, Citation2014; Xu et al., Citation2021). Eight studies explored elements relating to mental health and well-being protective factors such as coping, social support, resilience, mindfulness frequency and states, and emotional expression (Ireland et al., Citation2007; Joyce et al., Citation2019; Leonard & Alison, Citation1999; McKeon et al., Citation2021; Pinks et al., Citation2021; Shochet et al., Citation2011; Skeffington et al., Citation2016; Xu et al., Citation2021). Only one study (Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017) obtained organisational outcomes by examining the rate of absence due to illness. Other outcomes included satisfaction with the intervention or service (Shakespeare-Finch & Scully, Citation2004), knowledge and skills acquired (Lewis et al., Citation2013; Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017; Muller et al., Citation2009), perceived usefulness of the program (Shochet et al., Citation2011), barriers to implementation (LaMontagne et al., Citation2021), and acceptability of the intervention and changes to intentions, attitudes and behaviour (Fogarty et al., Citation2021; Robinson & Mitchell, Citation1993).

Intervention and initiative effectiveness

Of the 19 included studies, 11 examined outcomes related to mental health and well-being. Of these, three explored the effectiveness of psychological debriefing and positive results were reported. Leonard and Alison (Citation1999) found that anger decreased and social support increased; Robinson and Mitchell (Citation1993) found that stress symptoms and the impact of the event were reduced; Tuckey and Scott (Citation2014) found that alcohol use was reduced and quality of life was higher. However, two studies found that debriefings had no significant effect on PTSD, psychological distress, or physical health (Addis & Stephens, Citation2008; Tuckey & Scott, Citation2014).

Other studies examining mental health literacy program for managers, emotional disclosure in writing, mindfulness smartphone app, social support and physical activity, all reported improvements to employee mental health or well-being (Ireland et al., Citation2007; McKeon et al., Citation2021; Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017; Pinks et al., Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2021). Outcomes included reduction in work-related sick leave (Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017), improvements in emotion-focused coping and emotional expression (Pinks et al., Citation2021), improved quality of life (McKeon et al., Citation2021) decreased anxiety and stress (Ireland et al., Citation2007; Xu et al., Citation2021, Citation2021) and improvements in overall well-being (Tunks Leach et al., Citation2021). One intervention that focused on resilience training for the prevention of PTSD for trainee firefighters obtained no significant difference in PTSD, mental health symptoms, social support, or coping strategies compared to a control group (Skeffington et al., Citation2016). In another intervention, mindfulness training for firefighters was found to improve adaptive resilience over time but did not improve bounce-back resilience (the ability to recover from stress) or acceptance and mindfulness skills (Joyce et al., Citation2019). Finally, six studies examined outcome measures that did not directly assess mental health or well-being. These included satisfaction with the intervention or service and changes to intentions and attitudes. Consequently, the effectiveness of the interventions at improving mental health and well-being could not be evaluated in these studies (Fogarty et al., Citation2021; LaMontagne et al., Citation2021; Lewis et al., Citation2013; Muller et al., Citation2009; Shakespeare-Finch & Scully, Citation2004; Shochet et al., Citation2011).

Discussion

The current review aimed to investigate the mental health and well-being initiatives/interventions implemented with Australian and New Zealand emergency service workers including the evaluation methods used, and an assessment of their effectiveness. The quality assessments revealed that almost half of the studies were of a high standard overall, and over half were secondary interventions. While social support has been found to provide a positive effect on mental health (Shakespeare-Finch et al., Citation2015; Skeffington et al., Citation2017), only one study explored social support and utilised a student paramedic sample who had not commenced working fulltime (Pinks et al., Citation2021). Whilst the study was of good methodological quality and showed promising results, the likelihood of experiencing negative outcomes from emergency service work increases with length of service (Lawrence et al., Citation2018) which limits the generalisability of these findings to a continuing workforce. Further to this, sixteen of the included interventions were short-term interventions with a defined start and end time, only two ongoing initiatives involving ambulance chaplains and an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) were found through the search. Research highlights how emergency services work involves minimal recovery time and contributes to fatigue and negative mental health and well-being (Lawrence et al., Citation2018; Lawn et al., Citation2020). As such, there is a need for research to investigate and evaluate ongoing initiatives that provide continuous support.

Of the nine studies with good methodological quality, various outcomes were obtained. Interventions relating to mindfulness, physical activity, manager mental health training, psychological debriefing, and social support reported improvements in mental health and well-being (Joyce et al., Citation2019; Leonard & Alison, Citation1999; McKeon et al., Citation2021; Milligan-Saville et al., Citation2017; Pinks et al., Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2021). However, as noted earlier, Pinks et al. (Citation2021) study had limitations relating to the student sample. A study conducted by Skeffington et al. (Citation2016) produced an unexpected outcome. Despite a strong study design and intervention grounded in resilience, mindfulness, and PTSD research, they found no significant effect on preventing mental health issues, social support, or coping strategies. They noted that the training had been reduced from the recommended minimum of eight hours to four hours, which may have limited the impact of the training. This is consistent with Wild et al. (Citation2020) argument that for an intervention to be effective it requires adequate time, with an increased number and frequency of sessions ultimately producing greater improvements. Contrary to this, the study by Ireland et al. (Citation2007) involved emotional disclosure in writing for only 15 minutes per day for four consecutive shifts and still found a significant decrease in anxiety and stress. However, this study lacked clear reporting on inclusion and exclusion criteria of participants and sample size justification, and had threats to internal validity.

Consistent with the findings in the Cochrane review of psychological debriefing conducted by Rose et al. (Citation2003), the four studies that focused on debriefing produced different outcomes. Two studies found that psychological debriefing had no effect on post-traumatic stress, psychological distress, or physical health (Addis & Stephens, Citation2008; Tuckey & Scott, Citation2014). However, Tuckey and Scott (Citation2014) did find that alcohol use was reduced and quality of life improved. Leonard and Alison (Citation1999) also obtained positive outcomes, showing decreased anger and increased social support after debriefing. Another study reported a decrease in personal impact of the trauma and reduced stress symptoms, however the study provided limited information about the structure and implementation of the intervention to ensure consistency, and on the measurement tools that were developed by the research team to demonstrate validity and reliability (Robinson & Mitchell, Citation1993). These findings are consistent with the broader literature which suggests that single-session psychological debriefings do not prevent the onset of mental health issues (Rose et al., Citation2003), and in some instances increase the likelihood of developing PTSD (Devilly et al., Citation2006).

Evaluation methods varied across studies. Seven out of 19 studies were designed as RCTs, and five of these were conducted in the last five years, suggesting an increase in methodological rigour in recent times. The inclusion of psychometrically robust outcome measures that directly assess mental health or well-being was limited. An ambulance chaplaincy initiative was evaluated qualitatively, and whilst participants reported improvements to well-being, the study did not have a psychometrically validated measurement component (Tunks Leach et al., Citation2021). Six of the studies used outcome measures relating to perceived usefulness of the program, barriers to implementation, increased awareness, self-reported implementation, self-perceived capacity and acceptability of the intervention, and changes to intentions, attitudes and behaviour (Fogarty et al., Citation2021; LaMontagne et al., Citation2021; Lewis et al., Citation2013; Muller et al., Citation2009; Shakespeare-Finch & Scully, Citation2004; Shochet et al., Citation2011). Whilst these outcome measures are still important to consider, used in isolation they limit the conclusions that can be made regarding the usefulness of these interventions in improving mental health and well-being.

When reviewing sample characteristics, studies with mixed-service populations were well balanced across genders, however, the firefighter and police studies were consistently male dominated with little to no female representation. This reflects the current firefighter workforce in Australia (Bailey, Citation2018), but it may limit the generalisability of the findings across all emergency services sectors, such as for police and paramedics, where there is a greater degree of gender diversity (Australian Government Productivity Commission, Citation2019; Victorian Government Health Information, Citation2017). The study by McKeon et al. (Citation2021) was well designed, however it had the smallest sample size of 12 first responders. This was also a pilot study, so while the outcomes are promising, further research is required.

There is a need for future research to examine interventions that can support the unique challenges Australian and New Zealand emergency service workers face, particularly for small stations in rural and remote areas and with many volunteers in the fire service. No research included in the review, targeted these unique circumstances. Further research is also needed to explore primary interventions at the organisational level to enable a preventative approach, such as those improving leadership support or cultural changes to reduce stigma, to minimise the onset of mental health issues in these populations. Coordinating such interventions at a national level could introduce implementation challenges where multiple state-based operations need to be accommodated. To date, secondary interventions at the group level are more common which are helpful for addressing the early signs of mental health concerns, however they are not preventative in nature and may not address some of the root causes of mental health issues.

Interventions could also target the culture of emergency service organisations to reduce the stigma associated with mental health issues, and improve managerial response to staff reporting mental health and well-being concerns. Other interventions in need of further research include those that target social support, resilience, sleep, alcohol consumption, mental health issues and well-being. These are all areas in need of attention for improving the well-being of emergency service workers (e.g., Lawrence et al., Citation2018). Additionally, with 10 of the studies rating as ‘poor’ or ‘fair’ methodological quality, there is also a need to improve the scientific rigour of the research base. This could be done by ensuring use of psychometrically validated outcome measures or employing RCT study designs where possible. This would improve the research base to adequately inform best-practice initiatives and interventions to implement with emergency service workers.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, because of the diversity of study designs and small number of studies identified for this review, a quantitative meta-analysis could not be conducted. The supplementary information document provides a summary of studies and outcome measures that could assist with future meta-analytic work. Only five studies examined comparable outcomes and all the interventions had substantial variation in the type, duration, and delivery format making them unsuitable for meta-analysis synthesis. Second, the review focused on research published in the scientific literature, which may reflect only some of the interventions currently occurring in industry. It is possible that some programs, particularly initiatives, conducted with emergency service workers may only be published in government reports and lack evaluation in the scientific literature. It is also likely that interventions are more likely to be published if they show evidence of being effective. Future reviews could consider including grey literature to assist in understanding the mental health and well-being interventions and initiatives currently being implemented with emergency service responders. This was not undertaken in the current review which aimed to explore scientific literature due to a need to focus on evidence-based practice in emergency service organisations (Black Dog Institute, Citation2018).

Conclusions

The results of this systematic review contributed to the existing body of research by identifying and evaluating studies focused on mental health and well-being interventions and initiatives for emergency service workers in Australia and New Zealand. Nineteen studies were eligible for inclusion, less than half were assessed as good quality overall and ten were conducted in the last five years, suggesting this is an emerging area of research. The interventions that led to improvements in mental health and well-being were those related to mindfulness, physical activity, manager mental health training, social support, psychological debriefing, and an ambulance chaplaincy initiative. This review found a scarcity of research examining social-support-based interventions which have previously been found to be a key protective factor for improving the mental health outcomes of emergency service workers (Shakespeare-Finch et al., Citation2015; Skeffington et al., Citation2017). The findings also revealed only two ongoing and self-sustaining evidence-based mental health initiatives to mitigate daily stress for emergency worker populations in Australia and New Zealand. Considering the critical role of emergency service workers within the community, there is a clear need to conduct further research into activities that enhance the mental and physical well-being of this essential workforce.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Preregistered. The materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/PWSC6.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2022.2123282

References

- Addis, N., & Stephens, C. (2008). An evaluation of a police debriefing programme: Outcomes for police officers five years after a police shooting. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 10(4), 361–14. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2008.10.4.092

- Alden, L. E., Matthews, L. R., Wagner, S., Fyfe, T., Randall, C., Regehr, C., White, M., Buys, N., Carey, M. G., Corneil, W., White, N., Fraess-Phillips, A., & Krutop, E. (2020). Systematic literature review of psychological interventions for first responders. Work and Stress, 35(2), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2020.1758833

- Australian Government Productivity Commission. (2019). Report on Government Services 2019. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2019/justice/police-services

- Bailey, N. (2018). Women and Firefighting Inc (WAFA) Board: 2018 Conference Outcomes Statement. https://wafa.asn.au/uploads/pdfs/Outcomes-Statement-Full-V1.4.pdf

- Balmer, G. M., Pooley, J. A., & Cohen, L. (2014). Psychological resilience of Western Australian police officers: Relationship between resilience, coping style, psychological functioning and demographics. Police Practice and Research, 15(4), 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2013.845938

- Barratt, P., Stephens, L., & Palmer, M. (2018). When helping hurts: PTSD in first responders. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2018-06/apo-nid180066.pdf

- Black Dog Institute. (2018). Submission by the Black Dog Institute: Inquiry into the role of Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments in addressing the high rates of mental health conditions experienced by first responders, emergency service workers and volunteers. https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/bdi-submission-to-senate-inquiry-into-mental-health-of-first-responders.pdf?sfvrsn=0

- Bronitt, S., & Finnane, M. (2012). Comparative perspectives on Australia-American policing. Journal of California Law Enforcement, 46(3), 18–22.

- Cart, J. (2019). When it comes to wildfires, should California be more like Australia? https://calmatters.org/environment/2019/11/wildfires-should-california-act-like-australia/

- Courtney, J. A., Francis, A. J. P., & Paxton, S. J. (2010). Caring for the carers: Fatigue, sleep, and mental health in Australian paramedic shiftworkers. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Organisational Psychology, 3(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajop.3.1.32

- Covidence. (2014). Covidence systematic review software [computer software]. Veritas Health Innovation. www.covidence.org

- CSIRO. (2020). Understanding the causes and impacts of flooding. https://www.csiro.au/en/research/natural-disasters/floods/causes-and-impacts

- CSIRO. (2021). Preparing Australia for future extreme bushfire events. https://www.csiro.au/en/research/natural-disasters/bushfires/preparing-australia

- Devilly, G. J., Gist, R., & Cotton, P. (2006). Ready! Fire! Aim! The status of psychological debriefing and therapeutic interventions: In the work place and after disasters. Review of General Psychology, 10(4), 318–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.10.4.318

- The EndNote Team. (2013). EndNote (EndNote X9) [computer software]. Clarivate. https://endnote.com

- Fire and Emergency New Zealand. (2019). Fire and Emergency New Zealand. Annual Report. https://www.fireandemergency.nz/assets/Documents/About-FENZ/Key-documents/FENZ-Annual-Report-2018-2019.pdf

- Fogarty, A., Steel, Z., Ward, P. B., Boydell, K. M., McKeon, G., & Rosenbaum, S. (2021). Trauma and mental health awareness in emergency service workers: A qualitative evaluation of the behind the seen education workshops. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094418

- Gayton, S. D., & Lovell, G. P. (2012). Resilience in ambulance service paramedics and its relationships with well-being and general health. Traumatology, 18(1), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765610396727

- Harvey, S. B., Devilly, G. J., Forbes, D., Glozier, N., McFarlane, A., Phillips, J., Sim, M., Steel, Z., & Bryant, R. (2017). Expert guidelines: Diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in emergency service workers. https://phoenixaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/PTSD_emergency_service_workers_Guidelines-2.pdf

- Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2021). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.2 (updated February 2021). https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Ireland, M., Malouff, J. M., & Byrne, B. (2007). The efficacy of written emotional expression in the reduction of psychological distress in police officers. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 9(4), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2007.9.4.303

- Joyce, S., Shand, F., Lal, T. J., Mott, B., Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, S. B. (2019). Resilience@work mindfulness program: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial with first responders. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(2), e12894. https://doi.org/10.2196/12894

- Kirby, R., Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Palk, G. (2011). Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies predict post-trauma outcomes in ambulance personnel. Traumatology, 17(4), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1534765610395623

- Kyron, M. J., Rikkers, W., Page, A. C., O’Brien, P., Bartlett, J., LaMontagne, A., & Lawrence, D. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of suicidal thoughts and behaviours among Australian police and emergency services employees. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55(2), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420937774

- LaMontagne, A. D., Martin, A. J., Page, K. M., Papas, A., Reavley, N. J., Noblet, A. J., Keelgel, T., Allisey, A., Witt, K., & Smith, P. M. (2021). A cluster RCT to improve workplace mental health in a policing context: Findings of a mixed-methods implementation evaluation. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 64(4), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23217

- Lawn, S., Roberts, L., Willis, E., Couzner, L., Mohammadi, L., & Goble, E. (2020). The effects of emergency medical service work on the psychological, physical, and social well-being of ambulance personnel: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Psychiatry, 20(348), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02752-4

- Lawrence, D., Kyron, M., Rikkers, W., Bartlett, J., Hafekost, K., Goodsell, B., & Cunneen, R. (2018). Answering the call: National Survey of the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Police and Emergency Services. Detailed Report. Graduate School of Education, The University of Western Australia. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/docs/default-source/resources/bl1902-pes-detailed-report.pdf

- Lawson, K. J., Rodwell, J. J., & Noblet, A. J. (2012). Mental health of a police force: Estimating prevalence of work-related depression in Australia without a direct national measure. Psychological Reports. 110(3), 743–752. https://doi.org/10.2466/01.02.13.17.PR0.110.3.743-752

- Leonard, R., & Alison, L. (1999). Critical incident stress debriefing and its effects on coping strategies and anger in a sample of Australian police officers involved in shooting incidents. Work & Stress, 13(2), 144–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/026783799296110

- Lewis, V., Varker, T., Phelps, A., Gavel, E., & Forbes, D. (2013). Organizational implementation of psychological first aid (PFA): Training for managers and peers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(6), 619–623. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032556

- Mackinnon, K., Everett, T., Holmes, L., Smith, E., & Mills, B. (2020). Risk of psychological distress, pervasiveness of stigma and utilisation of support services: Exploring paramedic perceptions. Journal of Paramedicine, 17. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.17.764

- McKeon, G., Steel, Z., Wells, R., Newby, J., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., Vancampfort, D., & Rosenbaum, S. (2021). A mental health–informed physical activity intervention for first responders and their partners delivered using facebook: Mixed methods pilot study. Journal of Medical Internet Research Formative Research, 5(4), e23432. https://doi.org/10.2196/23432

- Milligan-Saville, J. S., Tan, L., Gayed, A., Barnes, C., Madan, I., Dobson, M., Bryant, R. A., Christensen, H., Mykletun, A., & Harvey, S. B. (2017). Workplace mental health training for managers and its effect on sick leave in employees: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry, 4(11), 850–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(17)30372-3

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

- Muller, J., MacLean, R., & Biggs, H. (2009). The impact of a supportive leadership program in a policing organisation from the participants’ perspective. Work, 32(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2009-0817

- National Institute of Health. (2014). Study Quality Assessment Tools. Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies and Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- New Zealand Police. (2021). New Zealand Police - Our Business. New Zealand Police: https://www.police.govt.nz/about-us

- Petrie, K., Gayed, A., Bryan, B. T., Deady, M., Madan, I., Savic, A., Wooldridge, Z., Counson, I., Calvo, R. A., Glozier, N., & Harvey, S. B. (2018). The importance of manager support for the mental health and well-being of ambulance personnel. PloS One, 13(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197802

- Pinks, D., Warren-James, M., & Katsikitis, M. (2021). Does a peer social support group intervention using the cares skills framework improve emotional expression and emotion-focused coping in paramedic students? Australasian Emergency Care, 24(4), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.auec.2021.03.005

- Pyper, Z., & Paterson, J. L. (2016). Fatigue and mental health in Australian rural and regional ambulance personnel. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 28(1), 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.12520

- Robinson, R. C., & Mitchell, J. T. (1993). Evaluation of psychological debriefings. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(3), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490060307

- Rose, S., Bisson, J., & Wessely, S. (2003). A systematic review of single-session psychological interventions (‘debriefing’) following trauma. Psychotherapy Psychosomatics, 72(4), 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1159/000070781

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., Rees, A., & Armstrong, D. (2015). Social support, self-efficacy, trauma and well-being in emergency medical dispatchers. Social Indicators Research, 132(2), 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0749-9

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Scully, P. (2004). A multi-method evaluation of an Australian emergency service employee assistance program. Employee Assistance Quarterly, 19(4), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1300/J022v19n04_06

- Shochet, I. M., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Craig, C., Roos, C., Wurfl, A., Hoge, R., Young, R., & Brough, P. (2011). The development and implementation of the promoting resilient offices (RPO) program. Traumatology, 17(4), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765611429080

- Skeffington, P. M., Rees, C. S., & Mazzucchelli, T. (2017). Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder within fire and emergency services in Western Australia. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12120

- Skeffington, P. M., Rees, C. S., Mazzucchelli, T. G., & Kane, R. T. (2016). The primary prevention of PTSD in firefighters: Preliminary results of an RCT with 12-month follow-up. PloS One, 11(7), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155873

- Smith, T., Hughes, K., DeJoy, D., & Dyal, M. (2018). Assessment of relationships between work stress, work-family conflict, burnout and firefighter safety behavior outcomes. Safety Science, 103, 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.12.005

- Smith, B. W., Ortiz, J. A., Steffen, L. E., Tooley, E. M., Wiggins, K. T., Yeater, E. A., Montoya, J. D., & Bernard, M. L. (2011). Mindfulness is associated with fewer PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, physical symptoms, and alcohol problems in urban firefighters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(5), 613–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025189

- Sofianopoulos, S., Williams, B., Archer, F., & Thompson, B. (2011). The exploration of physical fatigue, sleep and depression in paramedics: A pilot study. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 9(1), 990435. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.9.1.37

- St John Ambulance. (n.d.). Our people. St John Ambulance Services. https://www.stjohn.org.nz/what-we-do/st-john-ambulance-services/our-people/

- Tetrick, L. E., & Quick, J. C. (2011). Overview of occupational health psychology: Public health in occupational settings. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 3–20). American Psychological Association.

- Tuckey, M. R., & Scott, J. E. (2014). Group critical incident stress debriefing with emergency services personnel: A randomized controlled trial. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 27(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2013.809421

- Tunks Leach, K., Simpson, P., Lewis, J., & Levett-Jones, T. (2021). The role and value of chaplains in the ambulance service: Paramedic perspectives. Journal of Religion and Health, 61(2), 929–947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01446-9

- Varker, T., Metcalf, O., Forbes, D., Chisolm, K., Harvey, S., Van Hooff, M., McFarlane, R. B., Bryant, R., & Phelps, A. J. (2018). Research into Australian emergency services personnel mental health and wellbeing: An evidence map. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(2), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417738054

- Victorian Government Health Information. (2017). Woman power! http://www3.health.vic.gov.au/healthvictoria/aug17/ambo.htm#: :text=Ambulance%20Victoria%20is%20a%20leader,cent%20of%20graduate%20paramedic%20applicants

- Wild, J., El-Salahi, S., & Esposti, M. D. (2020). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving well-being and resilience to stress in first responders: A systematic review. European Psychologist, 25(4), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000402

- Xu, H. G., Eley, R., Kynoch, K., & Tuckett, A. (2021). Effects of mobile mindfulness on emergency department work stress: A randomised controlled trial. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 34(2), 176. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.13836

- Xu, H. G., Tuckett, A., Kynoch, K., & Eley, R. (2021). A mobile mindfulness intervention for emergency department staff to improve stress and wellbeing: A qualitative study. International Emergency Nursing, 58, 101039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2021.101039