ABSTRACT

Background

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth are vulnerable to racism, trauma and Lateral Violence (LV) where negative feelings and behaviours are directed towards members within their own oppressed group. Conversely, Lateral Empowerment (LE) is the collective prevention and repair of the effects of LV and promotes resilience and strength. There is limited peer reviewed literature directly relating to LV and LE.

Objective

This review focuses on grey literature to gain greater insight into the understanding and experiences of LV/LE among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people within Australia.

Method

This grey literature scoping review identified N = 38 documents between January 1980 and September 2023 related to LV or LE to gain a greater insight into the understanding of LV and LE among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community outside of published publications.

Results

The results elucidated that the experience of LV for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth is largely based upon internalised racism pertaining to Aboriginal identity. Strength-based gender-specific approaches which focus upon positive cultural experiences, the use of lived experience mentors and the inclusion of family were identified as the foundation for LE.

Conclusion

The grey literature review highlights that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community are taking an active role in addressing and preventing LV through culturally informed practices and approaches based upon the truth telling of Australia’s colonial history. There remains the need for specific approaches directed at Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth to help prevent and address LV/LE.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

LV is an emerging area of discourse within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities.

LV is prevalent within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities as a symptom of the ongoing oppression of colonisation, with young people particularly vulnerable and most at risk.

LE is a relatively new term that aims to counteract LV by empowering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to have control over their lives.

What the topic adds:

This analysis provides a thorough review of unpublished information (“grey literature”) pertaining to LV and LE for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within Australia, with a specific focus on young people.

Insight into the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and their communities in relation to their understanding and lived experiences of LV/LE.

Insight into the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth and their communities with regard to approaches to counteract the effects of LV.

Introduction

Lateral violence (LV)

Contemporary definitions of lateral violence (LV) describe it as the way people from oppressed groups direct their rage, fear, shame, anger and dissatisfaction towards themselves and other members of their own community due to their feelings of oppression and the continued experience as part of settler-colonialism (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2011c; Clark et al., Citation2016; Whyman et al., Citation2023). The conceptualisation of LV originally emerged from notable writings pertaining to colonialism and slavery literature (Fanon, Citation1967; Freire, Citation1970). LV can encompass feelings of distrust, mistrust and jealousy with behaviours such as gossiping, bullying, shaming, social exclusion and various forms of violence including domestic and family violence (DV and FV, respectively), social, physical, psychological, economic and spiritual violence (Clark et al., Citation2016).

Oppression theory describes how the lasting impacts of colonisation underpin the creation of LV among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (Vaditya, Citation2018). Wishing to avoid social disadvantage and ostracisation resulting from racist policies, the oppressed group attempts to follow the dominant group’s social norms, rules and laws. This assimilation process can create a collective sense of self-loathing and low self-esteem, resulting in strong behavioural undercurrents known as internalised oppression (Dudgeon et al., Citation2000). The oppressed group can develop deeply rooted resentment or anger towards the dominant group yet is unable to act against the dominant group, and resentment is turned inward towards the self or members of their own group enacted as LV. As described by Frankland and Lewis and quoted in the 2011 Social Justice Report, “When we are consistently oppressed, we live with great fear and anger, and we often turn on those who are closest to us” (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2011c, p. 52).

Impact of lateral violence on aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth

Evidence from a variety of sources suggests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people are particularly vulnerable to LV (G. Charles & DeGagné, Citation2013; Clark, Citation2017; Coffin et al., Citation2010; Herrenkohl et al., Citation2022). Marcia Langton (Citation2008) argued:

Those most at risk of LV in its raw physical form are family members and, in the main, the most vulnerable members of the family: old people, women and children. Especially the children. (p. 50)

Racism as a form of oppression has a considerable influence on social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) outcomes for young people. Witnessing and experiencing racism and LV can be internalised and normalised at a very young age, leaving children and adolescents at risk emotionally, mentally, spiritually and physically (Calma & Priday, Citation2011; Clark & Augoustinos, Citation2015; Priday et al., Citation2011; Svetaz et al., Citation2020). A systematic review by Priest et al. found a strong and consistent relationship between racial discrimination and negative mental health outcomes for young people, this means that young people could be prone to disorders such as anxiety, depression and psychological distress (Priest et al., Citation2013). A longitudinal Australian study on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 5–10 years old found an increased risk of asthma and obesity for children experiencing direct and prolonged racism (Shepherd et al., Citation2017). Collectively, racism, oppression and the effects of intergenerational trauma have led to young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experiencing LV, with dire consequences (Priday et al., Citation2011). The vulnerability of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth is evident in the epidemic levels of suicide among this group. Rates of suicide are three times higher in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth compared to non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, and suicide is the leading cause of death among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people aged 0–24 years, contributing to 22% of all deaths for this age group (Australian Insitute of Health and Welfare, Citation2024).

At present, there is limited guidance on managing, coping with and rectifying LV in the Australian context for young people, especially as LV is relational to other phenomena such as racism, discrimination and trauma. Some documented strategies to cope with and deter LV include avoidance, such as not identifying as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Bennett, Citation2014) or disengaging from family, community, school and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workplaces (Clark, Citation2017; Webster & Clark, Citation2024). Such strategies may contribute to further vulnerability and isolation.

Lateral empowerment

Although young people are the most vulnerable to LV (Svetaz et al., Citation2020), they are also the future change makers, as exemplified by an Aboriginal community member in Clark (Citation2017).

The future of Aboriginal communities lies with the next generation and therefore a focus on prevention and unity needs to start with young Aboriginal people. (p. 112)

Lateral empowerment (LE) is an emerging term describing interventions that aim to foster autonomy and self-determination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The term lateral love has also been used in the grey literature with messages and a call to action to counteract LV (Butler, Citation2013). Hence, having power over choices affecting their own lives, LE can be seen as a process to self-determine outcomes that can eliminate and counter LV (Alsop & Heinsohn, Citation2005). By empowering young people to make their own decisions and choices that counteract or decrease LV, and to support their peers to do the same, young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can gain a sense of control in their lives (Butler, Citation2013; Calma & Priday, Citation2011; Newton, Citation2016; Priday et al., Citation2011). Strategies to empower can include arming oneself with knowledge and awareness of LV, propping up support from family, community and workplaces, counselling, positive role modelling and challenging LV where it occurs (Clark et al., Citation2017). A holistic approach is needed to nurture the culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and families, and in turn, this will empower families to thrive and improve community and young people’s SEWB (Dudgeon et al., Citation2023; Durmush et al., Citation2021; Gee et al., Citation2014). Empowerment is also gained through “epistemic privilege” from which new and critical knowledge is gained and disseminated by Indigenous populations which counter the epistemic positions of the dominant colonial worldview. The prioritisation of epistemic privilege serves to challenge oppression through the use of Indigenous research methodology and change and challenge colonial social constructs (Vaditya, Citation2018). This review of grey literature leverages epistemic privilege by empowering the voice and resources of Indigenous populations that do not fall into the colonised academic structure of publication and peer review. Thus, this work amplifies and combines Aboriginal-led community voices into resources (grey literature) that can serve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Current objectives

Given that LV and LE are relatively new terms applied to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, there is limited information and literature in Australia making use of the terms “lateral violence” and “lateral empowerment” among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, including a lack of documented experiences and impacts of LV/LE for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth.

The authors acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, as it pertains in this review, have been categorised as a homogenous group and have not specifically identified the experience of LV/LE in subcultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth. This scoping review seeks to collate alternative sources of literature, known as “grey literature”, for the presence of LV and LE outside of the published peer-reviewed literature. Grey literature is a field that deals with the production, distribution and access to multiple document types produced at all levels of government, academics, business and organisations in electronic and print formats not controlled by commercial publishing (GreyNet International, Citation2024). Grey literature provides a platform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and organisations to publish work and other resources that are not based upon peer-reviewed studies, thereby increasing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander expertise in areas which directly impact the community. The methodology examining grey literature leverages epistemic privilege to amplify the knowledge contained in resources and reports collated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community organisations, and acknowledges that this knowledge is not, and should not be constrained by academic colonised pathways of dissemination. It can provide avenues for voices, resources and accessibility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This grey literature scoping review compliments a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature under review which explored LV and LE in young Indigenous populations across the Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and United States (CANZUS) nations (Hawke et al., Citation2024). Reviewing grey literature sources will allow further exploration of LV/LE from the perspective of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community. The purpose of this scoping review is to identify the breadth of grey literature available that pertains to LV and/or LE, and the impacts of LV and LE on young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; in particular, the aims of this review are to understand what community are saying about LV/LE, gauge understanding of LV/LE within the community and identify any targeted interventions and information relating to LV/LE available to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community in Australia.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The review of grey literature was conducted following a larger scoping review of peer-reviewed publications (Hawke et al., Citation2024) which identified several sources of grey literature. While these documents were out of scope for the larger review, the research team acknowledged the value of the grey literature documents for providing insight into the understanding of LV and LE in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia. The search was designed to identify all relevant literature and open access documents related to LV and/or LE and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and included search engines (Google.com), websites of Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCO) and one Indigenous-specific research database (Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet). Search terms were intentionally broad to return a wide variety of sources and documents. An overview of the hand-searched databases and websites can be found in .

The search included government reports, conference proceedings, research reports, fact sheets, health resources, websites and newsletters sourced from a range of organisational websites such as Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations, government and non-government agencies, research centres, health institutes and non-profit organisations ().

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review included any grey literature (as per the Prague definition) published in Australia between January 1980 and September 2023 that specifically reported direct or vicarious experiences of LV and/or LE among youth in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Though the focus of this review is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, no age-based exclusion criteria were applied. Documents were excluded if full text was unable to be retrieved. While the search terms were intentionally broad, documents were ultimately excluded if they did not specifically say the words “lateral violence” or discuss themes around lateral empowerment.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was designed to determine the variables to extract. Two reviewers extracted data (RE, FA) and assessed for consensus. Data items were not limited to specific definitions of violence or empowerment. The data items included but were not limited to 1) synonyms for LV and LE, 2) concepts/triggers that underpin LV and/or LE (e.g., LV: oppression, racism, intergenerational trauma, LE: identity, resilience), 3) behaviours associated with LV or LE (e.g., LV: bullying, covert/overt violence, LE: good mental health, help seeking behaviour) and 4) experiences and impact on health and SEWB outcomes (e.g., family relations, child and adolescent health and well-being, child development and functioning, criminal behaviours, spiritual health and well-being, and connection to culture and identity). Additionally, author background (i.e., whether Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander or non-Aboriginal) was recorded for each document, as were characteristics of the organisation that produced the document (e.g., government body, Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation, private individual, etc.). Eligible settings included but were not limited to justice systems, government organisations, workplaces, schools, community settings, child protection services, family, homes and health services.

Project governance and accountability

This project was entirely designed and driven from concept to synthesis by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander author specialists (YC, TC, NT, KH) in this field. Non-Aboriginal authors (FA, RE, AB, KP) supported the entire process and aided in screening, extraction and writing of the manuscript. The larger LV project was presented and discussed at an Aboriginal Communities and Families Health Research Alliance (ACRA) forum in November 2021 and since then there has been continual community consultation and yarning about LV and LE with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in SA, facilitated by YC and KH for feedback and perspectives on the project, and preliminary findings.

Results

Summary of literature search results

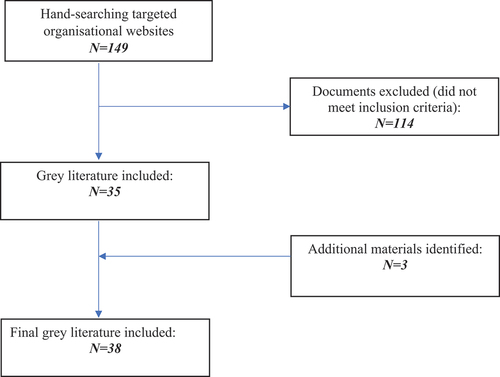

The grey literature search identified 149 results related to LV and/or LE in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. A total of 114 documents were excluded as not meeting the eligibility criteria. During the process of data extraction, a further three documents were identified that also provided insight or resources around LV in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, for a total of 38 pieces of grey literature included in this scoping review (see ). Documents and materials were further stratified into those that predominately focused on themes around LV (21 sources) and those themed around LE (17 sources) (see ).

Table 1. Document overview of the included literature.

Table 2. List of websites hand-searched for grey literature.

Of the 21 documents that addressed LV, the majority (15) were authored by an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person with or without non-Aboriginal co-authors. Two documents were authored by a non-Aboriginal person, and another was authored by a non-Aboriginal person who indicated that they consulted with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander community members. Three documents did not state the cultural background of the author(s). Of the 17 documents that addressed LE, 12 were authored by an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person, one was authored by a non-Aboriginal person, and four did not state authors’ cultural background.

Understanding and experiences of LV

There were several instances of educational documents, materials and resources produced specifically for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community around LV. Three gender- and age-specific resource kits were freely available from an Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation (ACCO) (Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Healing Service, Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2013c). These kits individually targeted men, women and children and defined and described LV, as well as discussing how it can be addressed. One privately owned Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation ran workshops exploring and addressing the concept of LV within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and professional settings (Big River Connections, Citation2021). A community training and counselling centre published a book describing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander narrative practices and previously delivered workshops exploring and addressing the concept of LV within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and professional settings (Wingard et al., Citation2012). One personal blog post detailed lived experience of LV pertaining to racism and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity (Cedar, Citation2023). One government resource provided education regarding LV within the workplace and how to create safe workplaces (SafeWork, Citation2023). Two government resources addressed the impact of LV and family violence on both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and youth (Education and Health Standing Committee, Citation2016; Queensland Government, Citation2022). Two online resources from a mental health service provided information about LV aimed at young people and their parents (ReachOut Australia, & Cox Inall Ridgeway, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). In addition, a report from a research organisation outlined the effects of LV in remote communities and the influence of government policies on LV (Bevis et al., Citation2020). Two reports and a related community guide produced by an independent statutory body discussed LV in the context of native title and human rights (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2011c).

Forms of LV – Internalised racism and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Identity

Different forms of LV identified within the grey literature describing the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were discussed within the context of internalised racism whereby Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander youth bully, shame or exclude peers based upon characteristics such as skin colour and bloodline. This brings into question a person’s sense of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity and was identified in two documents, which included a community youth website (ReachOut Australia, & Cox Inall Ridgeway, Citation2023b) and an editorial article from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander media source (B. Charles, Citation2023). The authors note internalised racism was also discussed as occurring among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on the website Creative Spirits (Korff, Citation2020). However, it is acknowledged by the authors that Indigenous forums (Indigenous & Flynn, Citation2024), alongside University reports (Sullivan & McLean, Citation2023) have questioned the authenticity and validity of this website and it was described as perpetuating negative stereotypes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, due to it being authored and disseminated by a non-Indigenous person, without consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people or community.

Causal factors of LV – Government policies and colonisation

Two documents identified causes of LV, which focused upon government political agendas within the National Indigenous Times (Loo, Citation2022). Additionally, the Social Justice Report reflected how contemporary political factors such as Native Title processes provided a system and environment for LV to thrive within families and communities. Although native title can generate positive changes, it can also fragment communities with opposing viewpoints regarding Native Titles, therefore generating LV to occur (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2011c). A further document discussed colonisation as an underlying cause of LV within the Native Title Newsletter due to policies which require Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to “prove their Aboriginality” (Weir & Barnes, Citation2011).

Understanding and experiences of LE

The source of documents addressing LE included four developed within an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander controlled research organisation, two from Australian universities, seven from Aboriginal Community Controlled SEWB services, two from state and territory governments, and one from a private individual representing a statutory body. A further one is from a non-Aboriginal mental health and overall health service.

Strengthening cultural identity and resilience – lived experience

To strengthen cultural identity and resiliency for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and address the impact of LV, a diverse set of mechanisms was recommended across the literature. Two documents reported utilising the lived experience of LV among community members, specifically domestic and family violence (DV and FV, respectively) to act as mentors to help support others who have experienced LV (Carnes, Citation2016; The Queensland Centre for Domestic and Family Violence Research, Citation2016). Additionally, the power of lived experience of DV was also used to support women by exploring personal narratives of DV and provided anecdotal strategies and approaches for how women have overcome DV to empower other women (The Queensland Centre for Domestic and Family Violence Research, Citation2016).

Family and cultural connection

Intergenerational trauma often underpins LV, and family-based interventions encompassing spiritual connection and healing were shown to improve SEWB, and cultural connectedness within families. This leads to greater capacity for behaviour change, and FV mitigation (McEwan et al., Citation2008). Demonstrating positive cultural experiences for youth was found to be instrumental in improving the SEWB of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth experiencing LV, particularly internalised racism. An article on the ReachOut website detailed an information sheet for parents on how best to support their children experiencing LV (ReachOut Australia, & Cox Inall Ridgeway, Citation2023a). This resource promotes positive cultural experiences, crediting both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander role models and celebrating young people’s efforts, talents and successes. Gender-specific Yarning circles were also noted as fundamental to providing a safe space for males and females to discuss their experiences of LV. These spaces lead to the development of culturally informed and appropriate strategies to address LV, empowering community with cultural knowledge and education about men’s and women’s roles, and the importance of positive role models for their families and children (The Healing Foundation, Citation2015; The Lowitja Institute, Citation2018).

Creative expression of LV experiences

Several grey literature resources used expressive creative modalities to provide education to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Aboriginal individuals about experiences of LV outside of traditional written forms. In total, five different creative modalities were identified. Multimedia was used by Black Lyrical Connection who developed Speak 2 Heal; a song writing program using local youth, Elders and community members to bring awareness of DV to the community (Desert Pea Media, Citation2015). Short films titled “Healing through voice, culture and country” narrated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members and practitioners were used to educate non-Aboriginal practitioners on how to better support and understand Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth and people experiencing DV and FV (Emerging Minds Australia, Citation2021). Cultural education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women about the strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and the traditional gender roles used as protective factors against DV and FV was expressed and presented in animation form “Old Ways are Strong; Sharing Knowledge for A Strong Future” (Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group and Men’s Behaviour Change Program, Citation2023). Digital storytelling “Stories of hope and resilience” was used as a way for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth and Elders to have a space to share their narratives and cultural knowledge as a mechanism to improve SEWB (The Lowitja Institute, Citation2010). Digital storytelling and film were also utilised as a modality for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men to share their cultural stories and strategies to remain strong and resilient in the face of adversity (Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, Citation2018).

Discussion

This overview of grey literature exploring LV and LE of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth enriches the understanding of what Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are saying about LV/LE, what communities understand of LV/LE and if there are any targeted interventions or information relating to LV/LE. Most of the grey literature available was produced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-controlled organisations and businesses and is written by community members. This demonstrated the integral role that communities have in creating resources that are led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This also highlights that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are aware of LV/LE and are proactive about addressing it. A breadth of literature concerning the different creative modalities for addressing LV/LE not only demonstrates the adaptive nature of support available but also the difference in needs and diversity of community settings.

Forms of LV identified within the grey literature detailing the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth were largely discussed within the context of internalised racism which were disseminated via youth-based website Reach Out. The lived experience of LV by way of “questioned Aboriginality” and Aboriginal authenticity due to skin colour was also shared via personal blogs disseminated via Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Broadcaster NITV. Such questioning is believed to stem from colonisation and historical government policies that at first categorised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people into colours and blood quantum such as “quadroons”, “quarter and half-castes” and “full bloods” (National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, Citation1997). Ironically Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are still required to “prove their Aboriginality”, to governments and in addition to each other, causing fragmentation within communities contributing to violence (B. Charles, Citation2023; Gooda, Citation2011). The firsthand recounts of intercommunity LV demonstrate that in-group racism is an ongoing concern, and that there is a desire from the community to raise awareness of its presence through experiences and story. This was especially poignant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth.

The grey literature provided a breadth of historical truth-telling by way of greater critical discussion regarding causes related to colonisation and the political agendas of successive Australia (Bevis et al., Citation2020; Weir & Barnes, Citation2011). A report developed by the Social Justice Commissioner described how contemporary political factors such as Native Title create an environment for LV to thrive within families and communities (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citation2011b). By provoking friction within communities relating to discussion such as identity, mining proposals and Native title, parallel to government disregard, or dictation of community hierarchy and voices, oppression caused by political agendas encourages LV (Loo, Citation2022).

The grey literature demonstrates that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are taking an active role in addressing LV within their communities and providing resources and strategies to address and identify LV. Yet there remained a paucity of resources and interventions available for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth, with only three organisations disseminating youth-specific resources addressing the impacts of LV on youth, forms of LV and strategies for adults on how to support youth experiencing LV (Big River Connections, Citation2021; Queensland Government, Citation2022; ReachOut Australia, & Cox Inall Ridgeway, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). Further youth targeted resources and interventions directly targeting experiences of in-group racism are needed to address LV among this cohort.

LE was highlighted within the literature as a mechanism to build capacity for healing, learning and adaption to both counteract and address the impact of LV on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by strengthening cultural identity and resiliency. Strength-based approaches focused on family-based approaches demonstrated positive cultural practices to strengthen cultural connectedness for youth and adults alike. These strategies were identified as key to increasing SEWB and, in turn, may serve to decrease incidences of LV. Furthermore, the grey literature highlighted the strength of gender-based strategies and support groups to strengthen cultural identity and improve SEWB among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Cultural education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women about the strength of their culture and the traditional gender roles used as protective factors against DV and FV was expressed and presented in animation form ‘Old Ways are Strong: Sharing Knowledge for A Strong Future (Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group and Men’s Behaviour Change Program, Citation2023).

The use of creative modalities for the expression of LV/LE reflects its utility, particularly in providing different options and opportunities for expression and healing among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and allowing for the dispersion of information to a wider audience that transcends age and gender. More importantly, this ensures the continued sharing of knowledge between youth and Elders to strengthen cultural identity and strength as demonstrated by “Stories of hope and resilience” (The Lowitja Institute, Citation2010) creating a space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth and Elders to share their narratives and cultural knowledge as a mechanism to improve SEWB. The sharing of cultural information was also demonstrated as a mechanism to teach men and women of the traditional roles in community which have been negatively impacted by colonisation as a way to enable cultural teachings and learnings to be carried down to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people and youth to create change to empower and reduce LV (Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group and Men’s Behaviour Change Program, Citation2023).

Strengths and limitations

The comprehensive grey literature review is a noteworthy strength that enabled the voice of both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people pertaining to LV/LE to be highlighted, who otherwise are often omitted due to being outside of the scope of published peer reviewed articles. It must be acknowledged that there are few traditional search strategies and methods for obtaining all grey literature, and while extensive hand searching was undertaken, grey literature may be missed due to the nature of fragmented and targeted publications. The authors’ views of where to search for grey literature concerning LV may have introduced bias to the results. This review was limited by the types of grey literature sources as Western methods bias written online literature. This means that sources such as podcasts, TV series and informal gathering/Yarning support groups were not included if they were not associated with written resources online. In future, it would be pertinent for future grey literature searches to include these forums. A further limitation concerns the lack of stratification or examination of subgroups within the focus population (e.g., LGBTQIA+ people, homeless people, single-parent families and adolescents or children in out-of-home care). It is acknowledged that LV may impact some groups disproportionately within our focus population, and future reviews should independently seek to examine literature associated with vulnerable populations.

This review drew on strengths by reviewing grey literature, which is more likely than commercial research publications to feature the voices and experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have traditionally been excluded from or underrepresented in commercial or peer-reviewed literature. However, the review was limited by an overall lack of materials relating to LV/LE, which are emerging topics within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community.

Conclusion

Findings of the grey literature review revealed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities within Australia are working to raise awareness of LV/LE and are taking active steps to address and counteract the impacts on their communities. The review elucidated that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth are exposed to in-group racism, family violence and bullying/harassment. Although the review noted few resources available to support youth in coping with LV and harnessing LE, there is a clear need for targeted interventions. Approaches found to be the most frequently offered utilise the creative expression of LV and incorporate strength-based interventions. This method of support is proposed to aid in integrating positive cultural experiences with gender-specific cultural traditions. Supports were noted to include family strategies occasionally to create a wholistic generational impact, reducing the ongoing occurrence of LV. Unfortunately, the sparsity of grey literature reinforces the notion that there still exists a need for resources targeted to whole family healing from the impact of LV.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement to all the authors who made a substantial contribution at various stages of the scoping review and who work within the Aboriginal Communities and Families Health Research Alliance (ACRA) team at SAHMRI Women and Kids theme. The work was supported by funding from NMHRC Early Career Research Fellowship that was awarded to Assoc/Prof Yvonne Clark.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known conflicts of interest that could influence the work presented in this paper.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings are found within the article. Any additional data can be made available upon reasonable request to the first author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation. (2012). Our healing our way. Alice Springs healing forum report. https://hdl.handle.net/10070/383664

- Adams, M. (2019). Valuing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young men. Edith Cowan University. https://www.lowitja.org.au/projects/young-men/

- Alsop, R., & Heinsohn, N. (2005). Measuring empowerment in practice: Structuring analysis and framing indicators. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, issue. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=665062

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2021). Dhelk Dja: Safe our way – strong culture, strong people, strong families. https://plan4womenssafety.dss.gov.au/initiative/dhelk-dja-safe-our-way-strong-culture-strong-people-strong-families/

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (Ed.). (2011a). 2011 Social justice and native title reports a community guide. Australian Human Rights Commission.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2011b). Native title report. Australian Government.

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2011c). Social justice report. Australian Government.

- Australian Insitute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Deaths by suicide among First Nations people. AIHW, Australian Government. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/populations-age-groups/suicide-indigenous-australians

- Bennett, J. M. (2014). Cultural marginality: Identity issues in global leadership training. In Advances in global leadership (Vol. 8, pp. 269–17). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1535-120320140000008020

- Bevis, M., Atkinson, J., McCarthy, L., & Sweet, M. (2020). Kungas’ trauma experiences and effects on behaviour in Central Australia (research report, 03/2020). https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/kungas-trauma-experiences-and-effects-on-behaviour-in-central-australia/

- Big River Connections. (2021). Aboriginal people & lateral violence. https://bigriverconnections.com.au/workshops/aboriginal-people-lateral-violence/

- Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Healing Service. (2013a). Boorndawan Willam children’s resource kit (B. W. A. H. Service, Ed.). Boorndawan William Aboriginal Healing Service.

- Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Healing Service. (2013b). Boorndawan Willam men’s resource kit (B. W. A. H. Service, Ed.). Boorndawan William Aboriginal Healing Service.

- Boorndawan Willam Aboriginal Healing Service. (2013c). Boorndawan Willam women’s resource kit.

- Butler, N. (2013). Understanding Brian Butler and lateral love. The Stringer: Independent news. https://thestringer.com.au/understanding-brian-butler-and-lateral-love-653

- Calma, T., & Priday, E. (2011). Putting indigenous human rights into social work practice (Vol. 64). Taylor & Francis.

- Carnes, R. (2016). Applying a we Al-Li educaring framework to address histories of violence with aboriginal women. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1841.6728

- Cedar, J. (2023). Lateral violence is killing our families and communities. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/lateral-violence-killing-our-families-communities-jahna-cedar-oam

- Charles, B. (2023). What is lateral violence and how do we deal with its many forms? Health and wellbeing. https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/lateral-violence-explained-how-to-deal-with-its-many-forms/f6s54whcp

- Charles, G., & DeGagné, M. (2013). Student-to-student abuse in the Indian residential schools in Canada: Setting the stage for further understanding. Child & Youth Services, 34(4), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2013.859903

- Clark, Y. (2017). Lateral violence within the Aboriginal community in Adelaide. From dilemmas to strategies [thesis]. University of Adelaide.

- Clark, Y., & Augoustinos, M. (2015). What’s in a name? Lateral violence within the Aboriginal community in Adelaide, South Australia. The Australian Community Psychologist, 27(2), 19–34.

- Clark, Y., Augoustinos, M., & Malin, M. (2016). Lateral violence within the Aboriginal community in Adelaide: “It affects our identity and wellbeing”. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing Te Mauri Pimatisiwin, 1(1), 43–52.

- Clark, Y., Augoustinos, M., & Malin, M. (2017). Coping and preventing lateral violence in the aboriginal community in adelaide. The Australian Community Psychologist, 28(2), 105–123.

- Coffin, J., Larson, A., & Cross, D. (2010). Bullying in an Aboriginal context. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100000934

- Desert Pea Media. (2015). Black lyrical connection - ‘speak 2 heal’. https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/key-resources/publications/?id=30721

- Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., & Walker, R. (2023). Embracing the emerging indigenous psychology of flourishing. Nature Reviews Psychology, 2(5), 259–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00176-x

- Dudgeon, P., Garvey, D., & Pickett, H. (2000). Violence turned inwards. In P. Dudgeon, D. Garvey, & H. Pickett (Eds.), Working with indigenous Australians: A handbook for psychologists (pp. 259–260). Gunada Press.

- Durmush, G., Craven, R. G., Brockman, R., Yeung, A. S., Mooney, J., Turner, K., & Guenther, J. (2021). Empowering the voices and agency of Indigenous Australian youth and their wellbeing in higher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 109, 101798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101798

- Education and Health Standing Committee. (2016). Learnings from the message stick: The report of the inquiry into Aboriginal youth suicide in remote areas. https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/commit.nsf/(Report+Lookup+by+Com+ID)/B7C324463C7E020A4825806E00050947/$file/161114+Aboriginal+Youth+Suicide+Draft+Report+FINAL+with+electronic+signature+17112016.pdf

- Emerging Minds Australia. (2021). Healing through voice, culture and country: Short films. Emerging Minds Australia.

- Fanon, F. (1967). Black skin, white masks. Grove Press.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Seabury Press.

- Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A., & Kelly, K. (2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice, 2(2), 55–68.

- Gooda, M. (2011). Strengthening our relationships over lands, territories and resources: The UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. James Cook University. https://www.jcu.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/789364/jcu_145042.pdf

- GreyNet International. (2024). Grey literature network service 2024. Retrieved June 20, 2023, from https://www.greynet.org/home.html

- Gulbin, M. (2015, June 11). Aboriginal wellbeing conference focuses on health and bullying. Daily Telegraph. https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/lismore/aboriginal-wellbeing-conference-focuses-on-health-bullying/news-story/b7602ecbc160cda825f58d49a1f73efa

- Hawke, K., Ali, F., Elovaris, R., Clark, S., & Clark, Y. (2024). A holistic view of lateral violence and lateral empowerment across indigenous CANZUS populations: A scoping review. Under review.

- The Healing Foundation. (2015). Our men our healing: Creating hope, respect and reconnection. Evaluation report November 2015. https://healingfoundation.org.au/app/uploads/2017/03/OMOH-60-pg-report-small-SCREEN-singles.pdf

- The Healing Foundation. (2016). Talking family healing: East Kimberley gathering report. https://healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/key-resources/publications/31871/?title=Talking+family+healing++East+Kimberley+gathering+report&contentid=31871_1

- The Healing Foundation. (2017). Torres Strait and Kaurareg Aboriginal peoples healing strategy. https://healingfoundation.org.au/app/uploads/2017/02/Torres-Strait-aKAPHS-new-cols-SCREEN.pdf

- Herrenkohl, T. I., Fedina, L., Roberto, K. A., Raquet, K. L., Hu, R. X., Rousson, A. N., & Mason, W. A. (2022). Child maltreatment, youth violence, intimate partner violence, and elder mistreatment: A review and theoretical analysis of research on violence across the life course. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(1), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020939119

- Indigenous, X., & Flynn, E. (2024, June 28). Twitter. Retrieved April 10, 2024, from https://twitter.com/IndigenousX/status/1144473447600234496

- Jackomos, A. (2014). International human rights day oration: Linking our past with our future: How cultural rights can help shape identity and build resilience in Koori kids. Indigenous Law Bulletin, 8(17), 20–23. https://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ILB/2015/17.pdf

- Korff, J. (2020). Bullying and lateral violence. https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture//people/bullying-lateral-violence?/Aboriginalculture/people/bullying-lateral-violence

- Langton, M. (2008). The end of ‘big men’ politics. Griffith Review, 22, 48–73. https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/the-end-of-big-men-politics/

- Loo, B. (2022). Lateral violence is rampant in the Aboriginal community, so what is it? National Indigenous Times. https://nit.com.au/18-05-2022/3081/lateral-violence-is-rampant-in-the-aboriginal-community-so-what-is-it

- The Lowitja Institute. (2010). Stories of hope and resilience: Using new media and storytelling to faciliate ‘wellness’ in Indigenous communities. The University of Queensland. https://www.lowitja.org.au/projects/stories-of-hope-and-resilience/

- The Lowitja Institute. (2018). Journeys to healing and strong wellbeing final report. https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/lowitja_consulting_journeys_to_healing_report.pdf

- McEwan, A., Tsey, K., & Empowerment Research Team. (2008). The role of spirituality in social and emotional wellbeing initiatives: The family wellbeing program at Yarrabah (Discussion paper series, issue). https://yumi-sabe.aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/outputs/2023-12/DP7_FINAL%20%281%29.pdf

- National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. (1997). Bringing them home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

- Newton, B. (2016). Understanding child neglect from an Aboriginal worldview: Perceptions of Aboriginal parents and human services workers in a rural NSW community. Uni of New South Wales Sydney.

- Northern Territory Government. (2018). Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Reduction Framework 2018–2028 (pp. 1–36). Alice Springs: Northern Territory Government, Department of Families Housing and Communities.

- Poche Centre for Indigenous Health. (2018). Roles and ritual: The Inala Wangarra Rite of Passage Ball case study. The University of Queensland. https://poche.centre.uq.edu.au/roles-and-ritual

- Priday, E., Gargett, A., & Kiss, K. (2011). Social justice report 2011. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social justice commissioner (social justice report). Australian Human Rights Commission. https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/social_justice/sj_report/sjreport11/pdf/sjr2011.pdf

- Priest, N., Paradies, Y., Trenerry, B., Truong, M., Karlsen, S., & Kelly, Y. (2013). A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Social Science & Medicine, 95, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031

- The Queensland Centre for Domestic and Family Violence Research. (2016). Strong women. Hard yarns. Stories and tips about domestic and family violence. Central Queensland University Australia, 1–40. https://noviolence.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/strongwomenhardyarns.pdf

- Queensland Government. (2022). Child safety practice manual; lateral violence. Queensland Government.

- ReachOut Australia, & Cox Inall Ridgeway. (2023a). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents and teenagers. https://parents.au.reachout.com/skills-to-build/wellbeing/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-parents-and-teenagers

- ReachOut Australia, & Cox Inall Ridgeway. (2023b). Changing the story: Turning around lateral violence. Pyrmont NSW. https://parents.au.reachout.com/skills-to-build/wellbeing/things-to-try-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-parents-and-teenagers/changing-the-story-turning-around-lateral-violence

- SafeWork, N. S. W. (2023). Lateral violence. NSW Government. https://www.safework.nsw.gov.au/safety-starts-here/our-aboriginal-program/culturally-safe-workplaces/lateral-violence

- Shepherd, C. C., Li, J., Cooper, M. N., Hopkins, K. D., & Farrant, B. M. (2017). The impact of racial discrimination on the health of Australian Indigenous children aged 5–10 years: Analysis of national longitudinal data. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0612-0

- Sullivan, C., & McLean, J. (2023). Contesting digital colonial power. The Routledge Handbook of Ecomedia Studies, 212–219. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003176497-26

- Svetaz, M. V., Barral, R., Kelley, M. A., Simpson, T., Chulani, V., Raymond-Flesch, M., Coyne-Beasley, T., Trent, M., Ginsburg, K., & Kanbur, N. (2020). Inaction is not an option: Using antiracism approaches to address health inequities and racism and respond to current challenges affecting youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 323–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.017

- Tangentyere Women’s Family Safety Group and Men’s Behaviour Change Program. (2023). Old ways are strong. Sharing knowledge for a strong future. iTalk Studio, Alice Springs, NT. 8CCC Community Radio. https://www.italkstudios.com.au/oldwaysarestrong/

- Vaditya, V. (2018). Social domination and epistemic marginalisation: Towards methodology of the oppressed. Social Epistemology, 32(4), 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2018.1444111

- Webster, T., & Clark, Y. (2024). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ understandings, experiences and impacts of lateral violence within the workplace. The Australian Community Psychologist, 32(1), 4–26.

- Weir, J., & Barnes, A. (2011). Native title conference 2011: Our country, our future [newsletter]. https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/journals/NativeTitleNlr/2011/15.html

- Whyman, T., Murrup-Stewart, C., Young, M., Carter, A., & Jobson, L. (2023). ‘Lateral violence stems from the colonial system’: Settler-colonialism and lateral violence in Aboriginal Australians. Postcolonial Studies, 26(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2021.2009213

- Wingard, B., Johnson, C., & Drahm-Butler, T. (2012). Aboriginal narrative practice: Honouring storylines of pride, strength and creativity (Dulwich Centre Foundation ed.). Dulwich Centre Foundation.