Abstract

A substantial proportion of adolescent antisocial behaviour (ASB) research has focused on identifying the chronic offender; comparatively little research has investigated developmental patterns among the general adolescent population, who account for a large proportion of ASB participation. A modified version of the Mak Self-Report Behaviour Scale was administered to 233 (relatively advantaged) community adolescents (aged 9–17), and 193 young adults (aged 18–25). Not available in previous instruments, in addition to prevalence rates, the Adolescent ASB Scale (AASBS) accurately identifies specifically when adolescents enter, exit, and peak in their ASB participation. An earlier age of ASB participation was associated with greater frequency, severity and duration. The most noteworthy finding was a mid-adolescent peak in ASB participation, which was shorter and more dramatic for girls. These findings provide knowledge critical for informing future research into causal explanations for the temporary and dramatic increase in adolescent ASB, and for developing more effective intervention practices with mainstream youth.

Antisocial behaviour (ASB) includes criminal behaviour, but also has been defined as any behaviour that is socially unacceptable or ignores the rights of others (Jacob Arriola, Citation2002). ASB ranges from relatively minor acts of nuisance behaviour (e.g., graffiti, prank calls) to serious criminal acts (e.g., property offences, theft, and physical assault) (Elliott & Menard, Citation1996). Of all the individuals who display this type of behaviour during their lifetime, only a small percentage shows a chronic pattern of ASB. Instead, for the majority, participation in ASB is limited to the period of adolescence (e.g., Moffitt, Citation1993); among those adolescents who come into contact with the law, only approximately 10% will continue this pattern of criminal behaviour as adults (Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, Citation2002). Thus, approximately 90% of adolescent ASB participators outgrow their ASB, even if the behaviour was serious enough to attract the attention of the legal system (e.g., Chen, Matruglio, Weatherburn, & Hua, Citation2005; Hua, Baker, & Poynton, Citation2006).

Adolescent ASB trajectories

Until approximately 20 years ago, information on ASB participation was limited to official crime statistics, which established that adolescents comprise the majority of the criminal offending population. These crime data show that participation rates decrease by >50% when individuals reach their early 20s, and (consistent with community sample findings, Moffitt, Citation1993), historically, <15% of adolescent offenders continue to offend beyond the age of 28 (Blumstein, Farrington, & Moitra, Citation1985; Farrington, Citation1986). Furthermore, internationally, the majority of juvenile offenders who come into contact with the criminal justice system do so only once (United States: Wolfgang, Figlio, & Sellin, Citation1972; United Kingdom: Prime, White, Liriano, & Patel, Citation2001; Australia: Coumarelos, Citation1994).

Until recently, comparatively little research has investigated developmental patterns among the mainstream adolescent population, despite this group also accounting for a large proportion of total ASB participation (New South Wales [NSW] Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Citation2000). Locally, Australian and New Zealand researchers have contributed substantially to this dearth of knowledge by conducting both cross-sectional (Baker, Citation1998), and longitudinal (Odgers et al., Citation2008; Smart et al., Citation2005, Citation2003), community-based studies examining, in part, trajectory patterns of ASB in adolescence through to adulthood.

Additionally, a substantial proportion of the research investigating developmental patterns in ASB has focused on identifying the chronic offender, defined as an individual who displays an enduring, high-frequency pattern of ASB participation (Blumstein & Cohen, Citation1987). Although representing a small percentage of offenders, these individuals are responsible for a disproportionately large amount of crime (Blumstein, Cohen, Roth, & Visher, Citation1986; Prime et al., Citation2001; Skrzypiec & Wundersitz, Citation2005; Tarling, Citation1993). Numerous community studies have identified distinct, life-course-persistent versus adolescence-limited, trajectory patterns (e.g., Moffitt, Citation2006), repeatedly finding that life-course-persistent adolescents continue ASB participation into early adulthood (Smart et al., Citation2005; Vassallo et al., Citation2002) and beyond (Odgers et al., Citation2008).

ASB measurement

Any study of ASB participation is complicated by the fact that several aspects of this behaviour must be considered in its measurement. Blumstein et al. (Citation1986) recommended that ASB participation be measured on four dimensions: (a) prevalence, (b) frequency, (c) career length, and (d) seriousness of the offences committed. Prevalence is defined as the proportion of the population who offend, and frequency is the average rate at which these active offenders commit ASB. The career length of an offender is the average duration over which they continue to commit antisocial acts, and “seriousness” is the severity level of the acts they commit. Data on each of these dimensions are necessary to arrive at a comprehensive picture of ASB participation.

Official crime statistics represent an objective outcome measure, but these types of data reflect only those incidents that are both detected, and prosecuted, by police (e.g., Coumarelos, Citation1994; Hua & Fitzgerald, Citation2006), and do not accurately reflect developmental transitions on the four ASB dimensions described above. Self-report surveys can obtain a more detailed picture of ASB participation in the general population, reflecting not only more-representative prevalence rates and types, but also frequency and duration of participation. Despite early criticisms that self-report data are limited by response bias (i.e., that people are not willing to report their own ASB), several studies have found that self-reported offending is reliable, and is a valid indicator of ASB (Hirschi, Hindelang, & Weis, Citation1982; Loza & Loza-Fanous, Citation2001).

Community adolescent ASB measures

The majority of community adolescent ASB self-report studies, however, have focused measurement efforts on establishing current prevalence rates among youth (e.g., Carroll, Durkin, Houghton & Hattie, Citation1996; Mak, Citation1993) and/or determining developmental trajectories over the lifespan (e.g., identifying early markers for severe, chronic participation) (Broidy et al., Citation2003; Odgers et al., Citation2008). Fewer studies have sought to describe how the frequency, severity levels, and duration of ASB participation vary according to age during the adolescent developmental period (e.g., Baker, Citation1998; Smart, Vassallo, Sanson, & Dussuyer, Citation2004).

In Australia, a substantial contribution to the field has been made with cross-sectional (Baker, Citation1998), and longitudinal (Smart et al., Citation2004), community-based studies, investigating the age at which adolescents are most at risk for specific types of ASB, as well as generally. Baker (Citation1998) found that, across most offence types, participation rates for the preceding 12 months were relatively high (15–30%) among 11–18-year-old NSW secondary school students, and that, compared to other age groups (11–13 and 17–18 years), boys and girls aged 14–16 years reported the highest level of ASB participation. Smart et al. (Citation2004) extended this type of research by identifying the percentage of Victorian community adolescents who engaged in ASB by offence type (e.g., property, violent, drug offences), in age groupings across the range 13–18 years.

ASB severity classifications can assist identification of individuals who report participating in non-normative behaviour (even for an adolescent) at a comparatively high level of ASB for their particular age. Smart et al. (Citation2004) discriminated between low- and high-severity participators by using age-sensitive ASB acts for different age groups, and found that a large majority of adolescents reported participation in particular acts (e.g., smoking, skipping school) at such high rates as to be considered a normative aspect of adolescence, whereas only a small group of adolescents reported participation in what could be considered relatively serious offences (e.g., breaking and entering, selling drugs).

Two alternatives to the Smart et al. (Citation2004) measurement methodology may provide incrementally valid ASB participation survey responses. One option is to derive ASB severity categorisations empirically (statistical item analysis), rather than by using theoretically derived groupings based on offence type similarity. A further option is to provide respondents of all age groups the opportunity to respond to all ASB items (rather than only those deemed as age appropriate), to potentially provide a more comprehensive picture of ASB prevalence rates by age. Combining these slight methodological changes, with a broader assessment of ASB participation type over the adolescent timespan (e.g., first and last age of participation in addition to ever or past 12 months' participation), may potentially provide a more comprehensive measure of ASB developmental patterns during the adolescent period, with a specific focus on identifying an age of peak first-engagement (“peak”) in ASB participation.

Study aims

The aim of this study was to contribute to the existing literature by replicating previous identifications of ASB trajectory patterns in community adolescents (e.g., Smart et al., Citation2005) but, more essentially, by identifying adolescence-limited, peak ASB participation patterns across the adolescent developmental period. Prior to this, the reliability and validity of a new self-report adolescent ASB measure is established. This measure was designed to provide a detailed account of, not only the prevalence rates of adolescent ASB participation, but also (a) the frequency of ASB participation across their adolescent lifetime, (b) current (past 12 months) participation, (c) the average number of years of participation, and (d) the age at which ASB participation typically begins and ends. The data on each of these dimensions separately, and in relation to each other, are then examined to identify specific developmental patterns in adolescence-limited ASB participation, in addition to potential life-course-persistent developmental trajectories.

Method

Participants and procedure

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and the NSW Department of Education and Training, Australia. A combined total of 426 adolescents (85 girls, 11–16 years, M = 14.2, SD = 1.24; 148 boys, 11–17 years, M = 15.0, SD = 1.54) and young adults (115 female, M = 20 years, SD = 3.6; 78 male, M = 20 years, SD = 2.9) participated in the study.

The sample was overrepresentative of economically advantaged Australians: the young adult sample consisted of UNSW first-year psychology students who participated in the study for course credit, and the majority of participants from Sydney metropolitan public secondary schools (average 8.9% response rate) were classified into either a high (60%) or moderate (20%) socioeconomic-status (SES) bracket using parent occupation data (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation1997), and the classification method of the Australian government's Department of Education, Science and Training (Jones, Citation2001). In comparison, the Australian national, and NSW average classifications were approximately 31% high and 43% moderate SES. Approximately 70% of the participants reported either an Asian (31%) or Australian/European (39%) cultural background.

All participants completed the 20-min Adolescent Antisocial Behaviour Scale (AASBS) as part of a larger study examining possible explanations for the relatively high prevalence rates of ASB exhibited during the developmental period of adolescence (Czech, Citation2008). There was no relationship between self-reported SES and ASB participation for either male or female subjects.

Antisocial Behaviour Survey

Although existing measures such as the Self-Reported Behaviour Scale (SRBS) (Mak, Citation1993) or the Carroll et al. (Citation1996) modified version of the SRBS are suitable for measuring the prevalence and variety of adolescent ASB participation, these instruments do not measure the frequency, severity, and duration of adolescent ASB. In light of this, the first author modified Mak's 40-item SRBS, to produce the AASBS. This modified scale expands the utility of the SRBS, because for each item, in addition to indicating whether they had participated in the behaviour within the past 12 months, the AASBS required respondents to indicate whether they had ever participated in the behaviour, the age of first participation, and, in the case of the young adults, the age of last participation.

Data treatment and statistical analyses

Scale construction

The internal and external validity, and internal reliability, of the AASBS were examined using comparisons to relevant external data sources (), and correlation, factor, and item analysis (). For reasons associated with time constraints and ethics, the adolescents and the young adults completed slightly different versions of the AASBS, but only items common to both versions are reported here.

Table I. SRBS subscales: Sydney vs. Canberra

Table II. AASBS Scale: % endorsed and factor loadings on 32 items (N = 420)a

Developmental patterns

Prevalence and severity

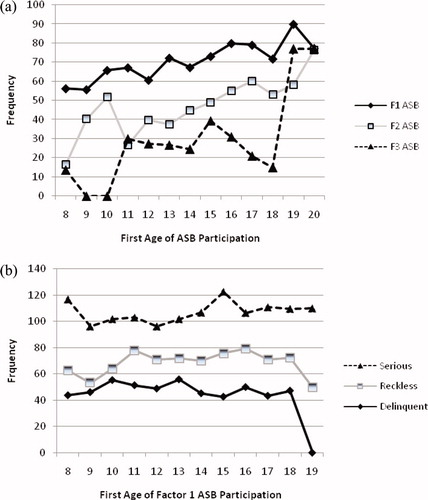

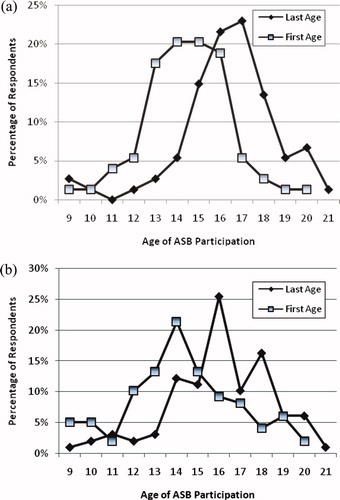

Because older participants have had more opportunity to participate in ASB, chronological age was controlled using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). (Although the use of ANCOVA in non-randomised designs has been the subject of some criticism, it has been suggested that this methodology may be useful when exploring a dataset such as this one to examine patterns of shared variance; Miller & Chapman, Citation2001.) Prevalence rates for each item were computed from total (cumulative) participation in ASB for adolescents and young adults separately and by sex (). Maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis with oblimin rotation was conducted to examine whether similar factors to those found by Mak (Citation1993) and Caroll et al. (1996) existed in the current sample. ASB severity levels were determined by applying principal axis factoring (). First age of ASB participation was identified separately for each severity level factor (Figure 1).

Frequency and duration

ASB participation frequency was measured for current participation and peak participation. Current (past 12 months) participation was examined separately by severity () and by age (). An age of peak ASB was calculated for young adult participants by identifying the age at which participation in new ASBs increased at the greatest rate (). Participation duration was defined as the number of years of ASB participation for young adults (participation had not yet stabilised for the adolescent group), and was computed by subtracting the average first age from the average last age of participation ().

The data were then examined for associations between first age of ASB participation and duration, current, and total (cumulative), ASB participation.

Results

Scale construction

Scale development

Developed by the first author; the AASBS consists of 32 ASB items, four lie and three validity scale items. The ASB items included 26 items from the Mak (Citation1993) SRBS, one item from the Carroll et al. (Citation1996) modified version of the SRBS, and four new items. All four lie-scale items and two of the three validity items were adopted from Mak's SRBS; one additional validity item was added by the first author.

Scale validity and reliability

Internal validity was examined by correlating participants' total-cumulative ASB with self-reported police warnings, court appearances, and court convictions. Participants' total scores were significantly (p < .0001) correlated with self-reported police contacts: several high-scoring adolescents (10.8% of girls, n = 9; and 12.6% of boys, n = 18; ρ = 0.41 ) and young adults (female, 19.1%, n = 22; male, 32.1%, n = 25; ρ = 0.45) reported having been warned by the police at some time in their lifetime, and a few high-scoring young adults reported significantly (p < .05) more court appearances (female, 2.6%; male, 3.8%; ρ = .16), or criminal convictions (male, 3.8%; ρ = .18).

Grouping items into the Mak (Citation1993) offence categories showed that mean current participation rates reported by the Mak Canberra secondary school sample (n = 103), and the current Sydney secondary schools sample (13–17-year-olds only; n = 190), were very similar. As shown in , on average, participating adolescents in both studies reported previous 12-months participation in one minor ASB (e.g., theft < $10), approximately half the sample admitted one moderate ASB (e.g., driving offences, fighting), and fewer than one in 10 reported a serious ASB (e.g., drug or vehicle offences).

Maximum-likelihood exploratory factor analysis on 32 items indicated an eight-factor solution with eigenvalues >1 and accounting for 51.1% of the variance (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index of sampling adequacy = 0.797; Bartlett's test of sphericity: p < .001, χ2 = 2624.0496). With factor loadings ranging between .21 and .98, eight constructs were identified similar to those found by Mak (Citation1993) and Carroll et al. (Citation1996): vandalism and public disorder, minor theft, major theft, motor vehicle offences, fighting, assault, drug-related offences, and fire-setting. Inspection of the scree plot indicated that a three-factor solution, accounting for 30.9% of the variance, may best delineate items with shared variance; therefore, principal axis factoring was performed prescribing a three-factor extraction with 25 iterations oblimin rotation (δ = 0).

The Cronbach (Citation1951) alpha coefficient of .84 indicates that the total scale () has good reliability, and the coefficients of .81 for Factor 1 (F1; 16 items) and .74 for Factor 2 (F2; eight items) are considered good and acceptable, respectively (Cronbach, Gleser, Nanda, & Rajaratnam, Citation1972). The coefficient of .64 on Factor 3 (F3; four items) is deemed questionable and most likely results from the very low number of items (Cronbach et al., Citation1972), and, additionally to the low level of endorsement in the current sample (although not considered reliable for assessment purposes, this factor was retained for research purposes). The three-factor structure may represent increasing severity levels of ASB: 1, delinquent (e.g., minor theft, vandalism, public nuisance); 2, reckless/personal harm (e.g., drug use, criminal driving offences); and 3, serious ASB (e.g., motor vehicle theft, drug offences).

Prevalence

All 32 ASB items were endorsed by at least one participant from the adolescent and young adult groups (grouped by factor in ). Some items were endorsed more frequently than others: approximately one third were each endorsed by >25% (n = 10 items), by between 10 and 25% (n = 10 items), or by <10% of the sample (n = 12 items). Theft and vandalism-related items were reported at consistent rates of between 15 and 40% across both samples, although more serious items were endorsed at a substantially higher rate by young adults than by adolescents (e.g., twice as many young adults [6.3%] than adolescents [3.1%] reported a break and entering offence).

Overall, male subjects reported participation in significantly more (n = 226; M = 5.4; 17% of total items) ASB than female subjects (n = 200; M = 3.9; 12% of total items; F3,423 = 18.343, p < .001), with an average participation rate across all 32 items of 20 and 14%, respectively. Driving-related offences were endorsed on average by approximately 10–40% of young adults, and were endorsed more frequently by male than female subjects, particularly vehicle racing (female, 8.7%; male, 41.6%); the exception to this was driving without a license, which was reported relatively frequently by both male (57.1%) and female subjects (32.2%).

Severity

Across all three factors combined, the age at which participants reported the greatest number of current ASB was 16 years, with a mean of 2.4 acts (). Across a 12-month period, F1-ASB was reported most often (nearly two acts); compared to F2-ASB (<1 act), and F3-ASB (fewer than one in 10 participants).

Table III. No. current and total (cumulative) ASB and age of first participation vs. severity factor (N = 426)

First participation in F3-ASB was reported at an older age (M = 14.1 years) than F1-ASB (M = 12.7 years), but a younger age than F2-ASB (M = 16.7 years). Adolescents who participated only in F1-ASB did so at a significantly younger age (M = 11.6 years) than adolescents who additionally participated in F2 (M = 13.4 years; t196 = 1.78, p < .001), or F3 (M = 13.6 years; t178 = 1.96, p < .001) ASB. On average, first participation in F2- and F3-ASB increased with age (), but reported first participation in F1-ASB remained relatively constant across the ages of 8–20 years, regardless of which severity level of participation the adolescent progressed to ().

Frequency

Cumulative participation by severity level

Only 8.2% (n = 35) of the sample reported participation in F3-ASB (); much lower than participation in F1-ASB (72.4%, n = 310), or F2-ASB (41.8%, n = 179). Compared to F1 and F2, F3-ASB participation was also associated with significantly greater participation frequency (F1: t241 = 9.17, p < .001; F2: t208 = 5.75, p < .001): of those engaged in F3-ASBs, >40% participated in a total of 15 or more ASB acts (), a further 40% reported participation in between 10 and 15 ASB acts, and <20% reported participation in fewer than 10 ASB acts. Comparatively, within each of Factors 1 and 2, the majority of the sample (approx. 60%) reported participation in fewer than 10 ASB acts.

Current and peak ASB participation rates by age

The highest mean rate of current ASB was reported by 16-year-old girls (M = 5.5 ASBs) and 17-year-old boys (M = 5.1 ASBs), followed by an immediate and continuous decrease for both girls (age 17), and boys (age 18; ). Examination of young adults' retrospective reports of ASB participation suggests that ASB participation first engagement begins to peak slightly earlier, but first engagement occurred at a mean age of 14 years old for girls (n = 97, SD = 2.8), and between the ages of 14 and 16 years for boys (n = 74, SD = 2.6; ). A progression in offence severity type by age was also observed (): graffiti, prank calls and minor theft/vandalism (M = 12–13.5 years); shoplifting, drug taking, damaging property and theft under $10 (M = 13.5–14 years); and vehicle-related offences, severely aggressive acts and selling drugs (M = 14–14.5 years).

Duration

Age of first and last ASB participation

The majority of young adult men (n = 74) and women (n = 98) retrospectively reported both their first, and last, ASB participation as occurring within an age range spanning 4 years (): first ASB commonly occurred between ages 13 and 16 years for boys (75% of sample), and between 12 and 15 years for girls (58% of sample); last ASB participation commonly occurred between 15 and18 years age for both boys and girls (75% of sample).

Number of years of ASB participation

On average, young adults reported participating in ASB for 1.8 years (SD = 1.8; female: n = 100, M = 1.7, SD = 1.7; male; n = 74, M = 1.9, SD = 1.8), and the modal response (48.4%) was <1.5 years. A small number of respondents reported participating in ASB for >5 years (10.8%) or >6 years (2.3%). Young adults who reported participation in only F1-ASBs reported a significantly average shorter ASB participation (2.5 years) compared to young adults who participated in both F1- and F2-ASBs (M = 3.4 years; t134 = 0.9, p < .05), or all three ASB factors (M = 6.8 years; t119 = 3.4, p < .001). Participants who engaged in the full range of ASBs (F1, F2 and F3) participated in F2-ASBs for significantly longer (M = 4.4 years; t119 = 2.4, p < .001) than those who engaged only in F1- and F2-ASBs (M = 2.0 years). Overall, participants reported engaging in F3-ASBs for approximately 1.6 years on average ().

Associations between age of first ASB and total participation

A large majority of respondents (male, 46.5%; female, 36.1%), reported participating in some form of ASB by the age of 9 years, and an additional 12.7% of female and 15.2% of male subjects reported first participation in one or more ASBs by age 12. Controlling for participants' chronological age, ANCOVA showed that early first-ASB participation (i.e., first participation in any ASB) was significantly associated with greater total ASB participation (F11,351 = 2.780, p < .005), and that an early average ASB participation (i.e., age of first participation averaged across all ASBs participated in) was significantly associated with greater current involvement in ASB participation (F50,62 = 1.938,p < .01), and participation for a greater number of years (F10, 161 = 2.825 p < .005).

Discussion

Psychometric evaluation of the AASBS indicated that self-report data collected from 426 adolescents and young adults were statistically reliable for the purpose of identifying adolescent ASB participation developmental patterns in the sample.

Prevalence and severity of ASB

The majority of adolescents reported participation in a wide range of ASB, including public disorder, status offences, vandalism, minor theft, and assault, and a small number of respondents reported participating in behaviours outside the normal adolescent range. These less common, but serious, ASBs are those that appear to be a marker for more significant, chronic, and early starting involvement in ASB (e.g., Hua et al., Citation2006).

Factor analysis identified three types of ASB participation: delinquent (common, low seriousness), reckless/dangerous (moderately common, moderately serious), and serious (relatively rare, but serious). Consistent with previous research (e.g., Bor, McGee, & Fagan, Citation2004; Moffitt, Citation1993; Smart et al., Citation2005), compared to adolescents who limited their ASB participation to less serious (i.e., Factors 1 and 2) behaviours, serious (Factor 3) ASB participators reported significantly greater total-cumulative ASB participation from a younger mean age (14.1 years) than participation in reckless ASB (16.7 years). Participation in reckless and serious ASB typically increased for some adolescents as they grew older, but those adolescents continued to participate in new lower level (i.e., delinquent) behaviours, indicating that participation at higher severity levels is associated with increased participation across all severity levels.

Frequency and age-related patterns of current ASB

The age at which young people are most at risk for past 12-months (current), and peak first engagement (peak), ASB participation frequency followed a distinct age pattern for male and female subjects separately.

Compared to boys, adolescent girls reported an earlier, more dramatic, and shorter, timespan for current ASB participation frequency, reporting a distinct peak participation age at ages 15 and 16, in comparison to boys' less-definitive peak participation at 17 years. Both groups then showed a sharp and continuous decrease in participation over subsequent years.

This slightly older age of reported current ASB compared to that found in other community samples (e.g., Baker, Citation1998: 14–16 years) may reflect a sample selection bias and/or a cohort effect. Prolonged engagement in adolescent ASB participation (Moffitt et al., Citation2002) may exist due to an extended period of dependence on parents that has been observed historically, particularly among young men (Rutter, Giller, & Hagell Citation1998). Given that the majority of responses (approx. 45%) were young adult retrospective reports, the participation age difference is more likely explained by a (self-selected) sample bias effect: higher and younger participation in crime typically occurs in comparatively lower-SES groups (Farrington, Citation1990).

Thus, the findings reported here are likely more representative of advantaged, rather than all, Australian adolescents. Further research examining the utility of the AASBS should be conducted in a diverse array of population samples including a more representative sample of the average adolescent, and examine the degree to which self-report in young adolescents is confirmed by other observers (e.g., parents and teachers).

Peak age of engagement in ASB participation

A dramatic increase in female subjects' reported peak first engagement in ASB participation at age 14, in contrast to more varied male reports, peaking at each of ages 14, 15, and 16 years, suggests that, similar to age of highest frequency participation, – compared to girls, adolescent boys' peak age of first engagement in ASB starts later, and for most, is more prolonged.

Several contributing factors may explain these developmental sex differences in ASB participation (Storvoll & Wichstrom, Citation2002), including the delayed maturation of male subjects mentioned above. A compelling physiological explanation is proposed, however: findings of a relationship between pubertal development onset and ASB participation (e.g., Caspi, Lynam, Moffitt, & Silva, Citation1993; Caspi & Moffitt, Citation1991; Felson & Haynie, Citation2002; Piquero & Brezina, Citation2001; Williams & Dunlop, Citation1999), combined with established sex differences in pubertal development (i.e., puberty onset occurs at an earlier age and for a shorter duration of time for girls than for boys; Kaiser & Gruzelier ; Paikoff & Brooksgunn, Citation1991), indicate that further research explaining associations between these two independent, but related, adolescent-specific events is needed, with a specific focus on sex differences. The research, to date, provides evidence that both internalising and externalising behaviours are associated with puberty onset, and that these associations are more pronounced in girls (e.g., Broidy et al., Citation2003; Caspi & Moffitt, Citation1991; Haynie, Citation2003; Stattin & Magnusson, Citation1990), than in boys (e.g., Felson & Haynie, Citation2002; Piquero & Brezina, Citation2001; Williams & Dunlop, Citation1999).

Duration of ASB participation

Confirmatory findings of a distinct sex difference in participation duration also support the above discussion points. Although 75% of both sexes reported a first, and last, age of participation spanning a period of 4 years, for girls, adolescent ASB participation was more concentrated and largely limited to a few years of active participation: nearly half of girls reported an average first age of 14 years, and one third reported an average last participation age of 16 years, in comparison to male reports of an evenly distributed first and last age of participation across the 4-year time span.

Similar to offender (e.g., Salmelainen, Citation1995), and general community-based samples (e.g., Bor et al., Citation2004; Smart et al., Citation2005), this SES-advantaged sample also showed significant associations between age of first participation and: (a) ASB severity, (b) a greater number of years of ASB activity, (c) a higher total ASB participation, and (d) greater participation in current ASB, thereby supporting previously reported findings that early participators are more likely to continue to participate actively in ASB as they grow older (Moffitt et al., Citation2002; Odgers et al., Citation2008). Thus, along with the above-reported finding that serious ASB participators were identifiable by the age of 14 years, these associations between early participators and greater, and longer, ASB participation – even in the relatively privileged sample reported here – suggest that early intervention to divert young people away from involvement in crime is necessary at all socioeconomic levels. As suggested in response to findings that even wealthy adolescent youth may be at risk for low academic achievement and problematic marijuana use, after-school programs may provide protection for youth who may have limited parental supervision after regular school hours (Ansary & Luthar, Citation2009). In addition to targeting these environmental influences, however, further investigation is needed to explore the extent to which physiological developmental changes may be associated with the adolescent ASB phenomenon.

Conclusion

Although some tools are available to assess levels and patterns of ASB among community adolescents, the AASBS builds on the work of Mak, and, with the addition of the work of Baker (Citation1998), Carroll et al. (Citation1996), Hua and Fitzgerald (Citation2006), Salmelainen (Citation1995), and Smart et al. (Citation2004), provides a more thorough and specific analysis to maximise measurement detail and accuracy of this important phenomenon. By including responses on first and last age of ASB participation, in addition to current and cumulative participation, and using principal axis factor analysis, the AASBS provides a comprehensive measure of the four dimensions (prevalence, frequency, duration, and severity) of ASB participation as recommended by Blumstein et al. (Citation1986).

The results of this study of 426 young Australian community male and female subjects between the ages of 11 and 25 years contributes substantially to other previously significant work internationally (e.g., Rutter et al., Citation1998). The study reported here expands on the current general understanding of adolescent ASB participation, not only by aiding identification of the persistent, high-frequency participator but, perhaps of equal importance, the normative developmental pattern for the average adolescent selected from relatively advantaged school communities in Australia. Replicating and extending this knowledge of the everyday occurrence of adolescent ASB, and the point in the lifespan at which this involvement (typically) begins, peaks, and ends, provides an information base for not only developing future intervention and/or diversionary programs for young people but, of equal importance, to inform future research investigating possible explanations for the temporary, and dramatic, rise in ASB during the period of adolescence.

Although the findings reported here may not be representative of the general adolescent population, they do provide evidence that even protected adolescents experience similar ASB participation patterns found in relatively disadvantaged populations. Arguably, a physiological explanation, rather than, or in addition to, environmental factors, may account for the large majority of adolescence limited, and, perhaps a minority of life-course-persistent ASB participators. It may be that all adolescents are at risk developmentally, but those who do not come into contact with the law do so because they have one or more protective factors (e.g., SES, school achievement, pro-social attitudes).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1997. Australian standard classification of occupations. 1997, Retrieved 24 March 2007, from http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/270547.

- Ansary, N. S., and Luthar, S. S., 2009. Distress and academic achievement among adolescents of affluence: A study of externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors and school performance, Development and Psychopathology 21 (2009), pp. 319–341.

- Baker, J., 1998. Juveniles in crime – Part 1: Participation rates and risk factors. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 1998.

- Blumstein, A., and Cohen, J., 1987. Characterizing criminal careers, Science 237 (4818) (1987), pp. 985–991.

- Blumstein, A., Cohen, J., Roth, J., and Visher, C. A., 1986. Criminal careers and career criminals. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1986.

- Blumstein, A., Farrington, D. P., and Moitra, S., 1985. Delinquency careers: Innocents, desisters, and persisters, Crime and Justice: Review of Research 6 (1985), pp. 187–219.

- Bor, W., McGee, T. R., and Fagan, A. A., 2004. Early risk factors for adolescent antisocial behaviour: An Australian longitudinal study, Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 38 (2004), pp. 365–372.

- Broidy, L. M., Nagin, D. S., Tremblay, R. E., Bates, J. E., Brame, B., and Dodge, K. A., 2003. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study, Developmental Psychology 39 (2003), pp. 222–245.

- Carroll, A., Durkin, K., Houghton, S., and Hattie, J., 1996. An adaptation of Mak's self-reported delinquency scale for Western Australian adolescents, Australian Journal of Psychology 48 (1996), pp. 1–7.

- Caspi, A., Lynam, D., Moffitt, T. E., and Silva, P. A., 1993. Unraveling girls delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior, Developmental Psychology 29 (1993), pp. 19–30.

- Caspi, A., and Moffitt, T. E., 1991. Individual differences are accentuated during periods of social change: The sample case of girls at puberty, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61 (1991), pp. 157–168.

- Chen, S., Matruglio, T., Weatherburn, D., and Hua, J., 2005. "The transition from juvenile to adult criminal careers". In: Crime and Justice Bulletin. Vol. 86. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 2005.

- Coumarelos, C., 1994. Juvenile offending: Predicting persistence and determining the cost-effectiveness of interventions. Sydney: New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 1994.

- Cronbach, L. J., 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests, Psychometrika 16 (1951), pp. 297–334.

- Cronbach, L. J., Gleser, G. C., Nanda, H., and Rajaratnam, N., 1972. The dependability of behavioral measurements: Theory of generalizability for scores and profiles. New York, NY: Wiley; 1972.

- Czech, 2008. Explanations for antisocial behaviour in adolescents: The role of pubertal development on cognitive processes. Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of New South Wales; 2008.

- Elliott, D. S., and Menard, S., 1996. "Delinquent friends and delinquent behavior: Temporal and developmental patterns". In: Hawkins, J. D., ed. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 28–67.

- Farrington, D. P., 1986. Age and crime, Crime and Justice: Review of Research 7 (1986), pp. 189–250.

- Farrington, D. P., 1990. Implications of criminal career research for the prevention of offending, Journal of Adolescence 13 (1990), pp. 93–113.

- Felson, R. B., and Haynie, D. L., 2002. Pubertal development, social factors, and delinquency among adolescent boys, Criminology 40 (2002), pp. 967–988.

- Haynie, D. L., 2003. Contexts of risk? Explaining the link between girls' pubertal development and their delinquency involvement, Social Forces 82 (2003), pp. 355–397.

- Hirschi, T., Hindelang, M. J., and Weis, J., 1982. On the use of self-report data to determine the class distribution of criminal and delinquent behaviour: A reply, American Sociological Review 47 (1982), pp. 433–435.

- Hua, J., Baker, J., and Poynton, S., 2006. "Generation Y and crime: A longitudinal study of contact with NSW criminal courts before the age of 21". In: Crime and Justice Bulletin. Vol. 96. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 2006.

- Hua, J., and Fitzgerald, J., 2006. "Matching court records to measure reoffending". In: Crime and Justice Bulletin. Vol. 95. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 2006.

- Jacob Arriola, K. R., "Antisocial behavior". In: Breslow, L., ed. Encyclopedia of Public Health, eNotes.com.2006. Retrieved 12 February 2010, from http://www.enotes.com/public-health-encyclopedia/antisocial-behavior.

- Jones, R. G., 2001. Identifying higher education students from low socio-economic status backgrounds and regional and remote areas. 2001, Retrieved 24 March 2007, from http://www.dest.gov.au/ sectors/higher_education/publications_resources/profiles/higher_ education_students_from_low_socio_economic_status.htm.

- Kaiser, J., and Gruzelier, J. H., 1999. The Adolescence Scale (AS-ICSM): A tool for the retrospective assessment of puberty milestones, Acta Paediatrica 88 (1999), pp. 64–68.

- Loza, W., and Loza-Fanous, A., 2001. The effectiveness of the self-appraisal questionnaire in predicting offenders' postrelease outcome: A comparison study, Criminal Justice and Behavior 28 (2001), pp. 105–121.

- Mak, A. S., 1993. A self-report delinquency scale for Australian adolescents, Australian Journal of Psychology 45 (1993), pp. 75–79.

- Miller, G. M., and Chapman, J. P., 2001. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance, Journal of Abnormal Psychology 110 (2001), pp. 40–48.

- Moffitt, T. E., 1993. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial-behavior: A development taxonomy, Psychological Review 100 (1993), pp. 674–701.

- Moffitt, T. E., 2006. "Life-course-persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior". In: Cicchetti, D., and Cohen, D. J., eds. Developmental psychopathology, Vol 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 570–598.

- Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., and Milne, B. J., 2002. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: Follow-up at age 26 years, Development and Psychopathology 14 (2002), pp. 179–207.

- New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, 2000. Who are the offenders?. 2000, Retrieved 10 May 2009, from http://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/bocsar/ll_bocsar.nsf/pages/bocsar_offenders_stats.

- Odgers, C. L., Moffitt, T. E., Broadbent, J. M., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., et al., 2008. Female and male antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes, Development and Psychopathology 20 (2008), pp. 673–716.

- Paikoff, R. L., and Brooksgunn, J., 1991. Do parent child relationships change during puberty, Psychological Bulletin 110 (1991), pp. 47–66.

- Piquero, A. R., and Brezina, T., 2001. Testing Moffitt's account of adolescence-limited delinquency, Criminology 39 (2001), pp. 353–370.

- Prime, J., White, S., Liriano, S., and Patel, K., 2001. Criminal careers of those born between 1953 and 1978. London: Home Office; 2001.

- Rutter, M., Giller, H., and Hagell, A., 1998. Antisocial behavior by young people. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

- Salmelainen, P., 1995. "The correlates of offending frequency: A study of juvenile theft offenders in detention". In: General Report Series. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research; 1995.

- Skrzypiec, G., and Wundersitz, J., 2005. Young people born 1984: Extent of involvement with the juvenile justice system. Adelaide: Office of Crime Statistics and Research; 2005.

- Smart, D., Richardson, N., Sanson, A., Dussuyer, I., Marshall, B., Toumbourou, J. W., et al., 2005. Patterns and precursors of antisocial behaviour: Outcomes and connections (Third Report). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies and Crime Prevention Victoria; 2005.

- Smart, D., Vassallo, S., Sanson, A., and Dussuyer, I., 2004. Patterns of antisocial behaviour from early to late adolescence, Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice 290 (2004), pp. 1–6.

- Smart, D., Vassallo, S., Sanson, A., Richardson, N., Dussuyer, I., McHenry, B., et al., 2003. Patterns and precursors of adolescent antisocial behaviour: Second Report: Types, resilience and environmental influences. Melbourne: Crime Prevention Victoria; 2003.

- Stattin, H., and Magnusson, D., 1990. Pubertal maturation in female development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990.

- Storvoll, E. E., and Wichstrom, L., 2002. Do the risk factors associated with conduct problems in adolescents vary according to gender?, Journal of Adolescence 25 (2002), pp. 183–202.

- Tarling, R., 1993. Analysing offending, data, models and interpretations. London: British Home Office; 1993.

- Vassallo, S., Smart, D., Sanson, A., Dussuyer, I., McHenry, B., Toumbourou, J. W., et al., 2002. Patterns and precursors of adolescent antisocial behaviour: First report. Melbourne: Crime Prevention Victoria; 2002.

- Williams, J. M., and Dunlop, L. C., 1999. Pubertal timing and self-reported delinquency among male adolescents, Journal of Adolescence 22 (1999), pp. 157–171.

- Wolfgang, M. E., Figlio, R. M., and Sellin, T., 1972. Delinquency in a birth cohort. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1972.