ABSTRACT

Objective

This paper reports on a critical survivor-driven study exploring how Australian lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer and asexual (LGBTQA+) adults attempt recovery from religious Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression Change Efforts (SOGIECE), and what supports they find useful in this process. The study privileged the critical communal lens of self-titled survivors of perspectives through its reference group, and applied Bronfenbrenner’s psycho-social lens, in an effort to ensure research used by psychologists was for and with survivors rather than on them.

Method

Qualitative data on SOGIECE survivor experiences and perspectives was collected using two focus groups and interviews including a total of 35 Australian SOGIECE survivors aged 18+ years.

Results

Findings suggested that post-SOGIECE recoveries were more successful if survivors experience three provisions: people who are affirming with whom to be freely themselves – especially health and mental health practitioners, family and friends, and survivor support groups; considerable time and internal motivation to enable support to be effective; and conflicting aspects of identities and beliefs are reconciled in ways that foreground survivors’ autonomy in their reconstruction.

Conclusions

SOGIECE survivors need recovery plans that consider complexities at all levels of their ecology of development; and diversify their exposure to affirming supports and ideas at all levels. Mental health practitioners should be especially careful to foreground survivors’ autonomy in therapies, recalling that they likely experienced past abusive therapies/therapy dynamics.

Key Points

What is already known about this topic:

People exposed to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression Change Efforts (SOGIECE) are at increased risk for many mental health conditions.

People exposed to SOGIECE are at increased risk of self-harm and suicide.

SOGIECE survivors need distinct treatment considerations distinguishing ‘pathology’ from SOGIECE’s ‘negative effects’, and challenging past social conformity-drives.

What this topic adds:

SOGIECE survivors need community (re)building aid in their recovery confluent with their own faith goals and avoiding conformity with therapists’ (faith-negative/faith-positive) ideals.

SOGIECE survivors need considerable time and different phases in recovery processes, to do developmental work discussing and reconciling dualities in identities, beliefs and social (re)engagements.

Support approaches and resources closely aligned to SOGIECE survivors’ presented identities were emphasised for the initial recovery decision-making, these could later vary more across treatment.

Introduction

Multiple psychological and rights bodies denounce religious Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity and Expression Change Efforts (SOGIECE) aimed at converting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer and asexual (LGBTQA+) people to fit cisgender heteronormative ideals as ineffective and harmful (American Psychological Association [APA], Citation2009; Australian Psychological Society [APS], Citation2010; United Nations, Citation2020). Various Australian states are responding by banning SOGIECE (e.g., ACT Minister for Social Inclusion and Equality, & ACT Minister for Justice Consumer Affairs and Road Safety, Citation2020; Queensland Government, Citation2020). Mental health professionals are hindered in supporting those recovering from SOGIECE (’SOGIECE survivors’), given scant research. This article outlines SOGIECE research through a survivor-driven psycho-sociological lens, reporting on an Australian study aimed at addressing data gaps on the recovery support needs of SOGIECE survivors. Survivors’ recovery needs are then framed for practitioners within Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological development model to show how they occur at several different psycho-social levels, and how they inter-relate.

SOGIECE literature

International psychological SOGIECE research includes substantial evidence from Western population surveys of the widespread prevalence of both sexuality- and gender-related conversion practices – experienced by between 7% and 20% of LGBTQA+ people depending on context (Blosnich et al., Citation2020; Ozanne Foundation, Citation2020; Green et al., Citation2020; Hurren, Citation2020; Salway et al., Citation2020; UK Government Equalities Office, Citation2018). Across the literature, gay men and transgender people were at especially high risk of exposure to SOGIECE, and the UK data showed Muslim and Black/African/Caribbean transgender people to be at particularly heightened risk. Socio-cultural research on SOGIECE movements’ approaches typically emphasises techniques from religious confession, psychoanalysis and addiction recovery programs (Bishop, Citation2019; Erzen, Citation2006; Waidzunas, Citation2015). Mostly US-based studies have shown SOGIECE’s (in)effectiveness (APA, Citation2009; Beckstead, Citation2020; Maccio, Citation2011; Serovich et al., Citation2008).

International studies of SOGIECE-related harms, mainly emphasising increased risks seen in trauma and suicide data, have emerged especially from the US, UK and Canada (Horner, Citation2019; Mallory et al., Citation2019; Salway et al., Citation2020; Schlosz, Citation2020; UK Government Equalities Office, Citation2018, Citation2021). Other trends across these data include increased anger; sexual and spiritual identity crisis/conflict and/or impaired self-concept; grief and loss of time and opportunity; escalated high-risk sexual behaviour and dysfunction; family break-down; depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress. A small international body of literature directly addresses recovery from SOGIECE (Flentje et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Haldeman, Citation2002; Horner, Citation2019; Lutes & McDonough, Citation2012; Maccio, Citation2011; Schlosz, Citation2020). Studies suggest SOGIECE survivors present distinct practice challenges that require special consideration in treatment; and clearly distinguishing ‘pathology’ from ‘negative effects’ of SOGIECE (Horner, Citation2019). Suggested approaches included integrative solution therapies, grief work, collaborative therapies, community-based and community-building interventions, trauma work and family support work offer healing strategies for recovery from SOGIECE and related harms (Horner, Citation2019; Lutes & McDonough, Citation2012; Maccio, Citation2011). There is no one validated model or archetypal recovery journey for survivors. However, the formation of a concept of self that is not ensconced in past conformity-drive around social or community structures is important (Haldeman, Citation2002).

Australian studies have also noted considerable harms from SOGIECE. A national survey found 7% of 3,134 same sex attracted and gender questioning Australians aged 14–21 were exposed to the message ‘gay people should become straight’ in sex education classes (Jones, Citation2015). Another survey showed that 4.9% of 2,500 (mainly cisgender and heterosexual) Australian students were exposed to the message ‘gay people should become straight’ in sex education classes (Jones, Citation2020). Those exposed were considerably more likely to consider self-harm (81.8%); attempt self-harm (61.8%); consider suicide (83.6%); and attempt suicide (29.1%). Further, a study of the 4% of 6,412 LGBTQA + Australians aged 14–21 years who attended SOGIECE practices and programs found they were also at significantly increased risk of having had a diagnosis for all 10 mental health conditions considered (Jones et al., Citation2021). This included being almost three-and-a-half times as likely to have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder/PTSD, and almost five times as likely to have been diagnosed with schizophrenia. A gap existed in Australian literature for a qualitative study on SOGIECE survivors’ recovery. The present study aimed to understand common themes across Australian SOGIECE survivors’:

experiences of recovery from SOGIECE? and

views on what support approaches or resources assist recovery?

SOGIECE survivor conceptualisations

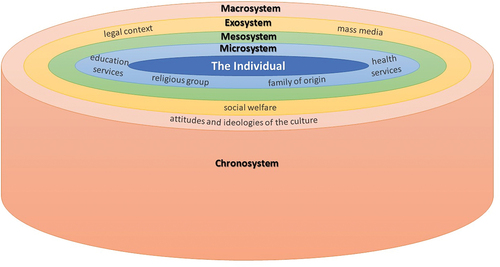

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological development model (Bronfenbrenner & Crouter, Citation1986) is considered beneficial in informing minority-inclusive policies and practices (Burns, Citation2011) and LGBTQA+ studies (Goldberg, Citation2014). It theorises ‘Individuals’ as centred in their development as autonomous and socio-cultural beings in their relationships to their gender, religious affiliations, mental health and other personal characteristics within five broad ecological systems (). These include the ‘Microsystem’ – institutional and social contexts individuals are frequently and repetitively directly exposed to; SOGIECE survivors frequently report anti-LGBTQA+ messages from family, teachers and peers in this system during their development (Jones et al., Citation2021). The ‘Mesosystem’ – includes interactions across Individuals’ Microsystems which they only indirectly experience; relations between SOGIECE survivors’ family, religious, educational and/or employment communities may be especially intwined (Horner, Citation2019; Jones et al., Citation2021). The Exosystem – includes institutional influences on Individuals and their Microsystems (media, law, health care). Surrounding these is the Macrosystem – cultural ideologies (including religious and LGBTQA+ sub-cultural ideals); and the Chronosystem – the time periods within which all systems shift. For Bronfenbrenner the Microsystem is most influential on individuals’ development including gender and sexuality, but the individual’s self-development of autonomy is most core and must be reconciled to their engagements with all systems’ influences (see Appendix).

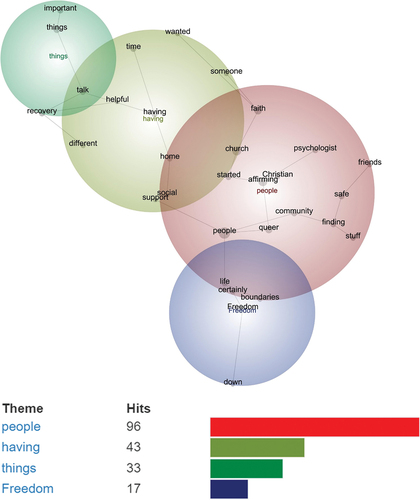

Figure 1. Leximancer themes for SOGIECE survivors’ comments on recovery.

The SOGIECE Survivor Statement (Csabs et al., Citation2020) outlines survivor-led definitions of SOGIECE terms affecting SOGIECE survivors’ ecologies. ‘Conversion ideology’ is conceptualised in the statement as the overt spoken beliefs/teachings, as well as the underlying culture of a particular community of people, that sees being LGBTQA+ as somehow broken or sinful, and in need of fixing or suppression. Related ‘pseudoscientific claims’ potentially contravene laws and ethics codes (APA, Citation2009; APS, Citation2010; United Nations, Citation2020). ‘Conversion practices’ are processes engaged in towards desired changes in gender and/or sexuality, including counselling, group work and prayer.

Methods

Emancipatory methodology

The study utilised a critical emancipatory methodology, aiming to work with, for and as, rather than ‘on’ a marginalised community, to enhance SOGIECE survivor community self-determination (Farrelly et al., Citation2007). The study was designed to benefit from ‘insider/outsider’ community dynamics (Davis, Citation2015) – including SOGIECE survivors as co-researchers. Constructivist grounded theory emphasising a relativist ontology was applied; presupposing the existence of manifold social realities in ways congruent with critical community-driven conceptual work (Charmaz & Bryant, Citation2011). The approach foregrounded participants’ and researchers’ co-constructions of knowledge and mutual interpretation of meaning above institutional perspectives, towards analysing participants’ experiences of the harms and catalysts for disengagement around conversion ideology and/or practices. Approval for the study was provided by La Trobe University’s (HEC19384) and Macquarie University’s (52020790617585) human research ethics committees.

Survivor focus groups and interviews

Recruitment for survivor focus group and interview sessions targeted LGBTQA+ adult Australians aged 18+ years formerly exposed to conversion ideology and/or practices. Data collection was piloted in 2016, and again conducted in 2020 (July–December). Focus Group sessions were conducted by the researchers online via Zoom, and ordered using a semi-structured questionnaire through a shared PowerPoint of questions and verbal prompts – lasting 2-3 hours each. Questions regarding conversion ideology and practices were developed and analysed with conversion survivors, including the ‘Brave NetworkFootnote1’ support group. The interdisciplinary research team also includes four LGBTQA+ conversion survivors (two religious, two now non-religious) and combined expertise in psychology, sociology, health, and history of religion. Recruitment strategies included emailed invitations sent out through networks of conversion survivors and snowballing/word of mouth, garnering a total of 35 participants.

supplies participant demographics from 15 in-depth life-history interviews with survivors of conversion practices conducted for the pilot study in 2016; a further seven in-depth life-history interviews conducted with survivors purposely recruited from multi-cultural multi-faith networks in 2020 (whose stories are primarised in another paper and thus reported in less detail here); and 15 survivors involved in survivor peer support groups from two 2020 focus group sessions (including two from the in-depth life-history interviews). Participants could choose their engagement level with all questions (turning their screen and microphone on/off as needed); their engagement level with support services available before, during and after recorded sessions; and their confidentiality level including transcript use/amendments.

Table 1. Participants’ demographics (N = 35*).

Data analysis

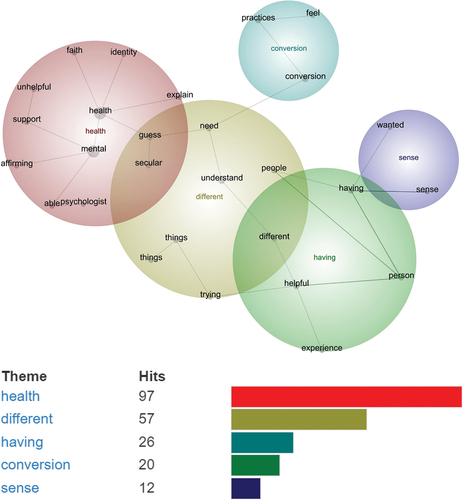

Initial codes were developed from the focus group data using Grounded Theory. Two fluid coding stages placed a focus on emergent categories/strategies (Charmaz & Bryant, Citation2011). The automated content analysis programme Leximancer, historically used in a variety of studies including in psychology (e.g., Cretchley et al., Citation2010) was firstly used to analyse data on transcript comments relating to each question area addressed in the focus group, on automatic settings (removing all transcript notes and merging singular and plural word forms). Leximancer uses word occurrence and co-occurrence counts to identify dominant themes and their sub-concepts, and how they relate to each other. Leximancer was applied to ensure the most dominant thematic concepts and the most ‘typical’ quote samples were identified and focussed on in a systematic way based on representativeness of the overall data, rather than extreme or one-off themes or examples. The reproducible computer analyses were also used to evidence ‘what was there’ and ‘most recurrent’ in the data, and how these concepts were related, by generating concept maps foregrounding participants’ concepts only. Settings were kept at ‘100% visibility’ so all themes Leximancer uncovered were visible, and ‘50% theme size’ so any common theme overlaps could be clearly seen. Further, concept ranking lists and vocabulary data were used based on the Leximancer algorithms as detailed and verified by Smith and Humphreys (Citation2006); for ‘showing’ (rather than imposing biases in ‘searching for’) all data concepts.

Recurring/significant Leximancer-identified concepts were then, secondly, elevated as provisional categories for theoretical sampling, and memo writing (tracing determining conditions, progression and consequence) using survivor-input as part of the analysis. Specifically, several of the researchers were survivors, and the team also held consultations with Brave Network representatives. Open coding processes included line-by-line coding, allowing interaction with each data piece by participants editing transcripts, and the research team using impressionistic memo writing, constant comparisons and cross-checking co-researchers and participants’ attributed ‘meanings’. Researchers adopted then interpreted the chief concerns of participants, and how they sought to resolve these concerns, as a way of focusing the analysis. Next, researchers engaged in coding actions to expose implicit processes, enabling the identification of connections between active and emergent codes. This inductively sourced categorical information was then considered against and interpreted deductively with reference to, the layers of the model of ecological development (Bronfenbrenner & Crouter, Citation1986). This model sees issues of individuals’ psychological wellbeing in terms of social groups and institutions, and broader cultural contexts, in ways befitting the SOGIECE survivors’ analyses of SOGIECE issues and allowing the insights of a broader socially driven psychological model to frame the community-based insights. The results section is structured around elevated Leximancer themes in survivors’ responses to the questions on first, recovery from SOGIECE, and second, on support resources.

Results

Recovery approaches

Being free with affirming people

SOGIECE survivors were asked about their experiences of their recovery approaches. Leximancer found three large themes in their responses: people, having and things (). The largest Leximancer-identified theme was ‘people’ (96 hits, 100% relationality to – meaning consistent co-occurrence with – all other concepts). This theme focussed on the importance of finding and surrounding oneself with affirming people (combining the sub-concepts: people, affirming, church, faith, queer, community, safe, started, finding, psychologist, Christian, life, friends, stuff). It was also overlapping with the concept ‘freedom’ (17 hits, 21% relationality). For most participants in this sub-concept, recovery involved seeking support from professionals or survivor support groups who were affirming and allowed them to feel free. For example, a bisexual white-AngloFootnote2 trans-woman (20s) said she was aided in recovery by ‘the psychologist, choosing my closest friends very carefully, so that they were all affirming, and creating boundaries with myself and with others’. A bisexual white-Anglo cis-woman (20s) said starting a queer relationship provided a good social network ‘of queer people from faith backgrounds whether they were still active in their faith’.

Comments described finding or becoming ‘allies’ as useful: ‘finding a psychologist who was affirming and really helpful, and getting more involved in the education about affirming theology’ (Orthodox Coptic Christian gay cis-man, 20s); ‘being there to be a support for another person’ and ‘being more strong for other people’ (white-Anglo gay Christian cis-men, 40s). Helping others especially mattered to people in support groups, for example a bisexual white-Anglo non-binary Christian (20s) said ‘I needed to explore my faith in more relational ways, through safe, affirming friends’. An asexual non-binary Christian (20s) said their friend started a queer affirming Bible study ‘which I went to really quietly and sat in the corner’; and through this connection they ‘started attending an affirming church’ that they ‘went to, met other queer Christians’. Meeting LGBTQA+ people with religious/atheist identities mirroring SOGIECE survivors’ combatted the widespread belief that ‘my two options were become straight in the church or leave my faith entirely … there was that other option’ (white-Anglo demi-romantic asexual Anglican cis-woman, 20s).

For some people, SOGIECE recovery processes included maintaining only affirming social contacts and removing all others. A bisexual white-Anglo trans-woman (20s) felt recovery required ceasing contact with ‘the majority of my family’, and an African refugee gay Muslim man (20s) was clear home was ‘necessary’. One gay cis-man (30s) similarly said, ‘there’s no one allowed in my life who’s not helpful or affirming (…) I just absolutely demand and require it’. A bisexual white-Anglo bisexual evangelical Christian cis-woman (20s) who had culled unsupportive people noted ‘it was really hard severing some of those ties, some quite obviously and some just letting them fall’. For some individuals this meant completely ‘leaving the church’ (South-East Asian cisgender lesbian, 30s); for others it included ‘this idea of I can be Christian but not attend a church’ (white-Anglo demi-romantic asexual Anglican cis-woman, 20s).

Having time for support to be effective

The second largest Leximancer-identified theme was ‘having’ (43 hits, 25% relationality to other concepts). This theme focussed on the importance of having time and support (combining the sub-concepts: having, time, home, social, support, different, helpful, someone, wanted). Several participants discussed that recovery could take ‘years’ and could involve multiple general practitioners, psychologists, counsellors and support group sessions to ensure the healing work was effective for their recovery. Several men reflected that they found the term ‘recover’ complex as it covered an ongoing project that, for example, required having time for support to really change their mentalities about their sexuality or their religious beliefs. One Presbyterian Anglo-Maori gay cis-man (30s) said, ‘recovery has this weird ring of that time to me’. A woman similarly said her recovery was lengthened and complexified by ‘chronic mental illness’ (white-Anglo asexual Anglican cis-woman, 20s).

SOGIECE survivors typically needed time to find supporters who could allow their changing religious (or atheist, or otherwise) views and their LGBTQA+ identities to co-exist in new and not mutually exclusive ways. One white-Anglo gay cis-man (30s) from a ‘charismatic Baptist’ background said, ‘One of the things that I found very hard when I first left was that I still wanted to retain my faith’. Like many other participants who typically experienced doctors and psychologists seeing faith and LGBTQA+ cultures and identities as mutually exclusive, he explained, ‘I could not find a doctor or psychologist that couldn’t differentiate between conversion, like the problem of conversion ideology and me wanting to retain my theology’. This meant that the participant disconnected from their support provisions, ‘I think that that lack of understanding was really detrimental to me seeking help from an actual qualified professional until much later when I ended up forgetting theology. So now I’ve been able to access great psychological care’.

Participants of various theist/atheist beliefs argued that time was needed in challenging and overcoming former false and misleading SOGIECE claims without necessarily challenging their need for faith. A bisexual white-Anglo trans-woman (20s) said that her support group often discussed ‘how we can’t sit in our pain and seek retribution because it just makes the wounds deeper’, but that survivors needed to use their time with the appropriate help to change their thinking. A decade receiving treatment from various therapists was needed to support a formerly Greek Orthodox gay cis-man (40s) to address panic attacks around SOGIECE identity conflicts, overcome ‘slut-shaming’ of his gay identity and finally face mortality fears when he became atheist. The therapists used questioning teachings, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), and queer affirmative methods beyond traditional psychology and psychoanalysis. Nonetheless, SOGIECE ‘have lifelong impacts and they are part of my daily reality’. Several participants described financial barriers to mental health time supports, and the need for government funding models. Recovery time thus needed to be made available, funded and generous, so it could be used productively.

Talking about and reconciling important things

The third largest Leximancer-identified theme was ‘things’ (33 hits, 43% relationality to other concepts). This theme focussed on the survivor’s need to be ‘talking about important things’ as part of recovery of individual self-hood – particularly the reconciliation of faith and sexual orientation and/or gender identity and expression (combining the sub-concepts: things, recovery, important, talk). Some of the most typical comments identified by Leximancer for this sub-concept included ‘being able to reconcile my faith and sexuality, I think for me that was really the foundation for me being okay in myself’ (white-Anglo bisexual Christian cis-woman, 20s) and ‘My psychologist giving me a young adult book about a Jewish gay boy, which was just really, at the time, quite formative for me to be able to reconcile my faith and sexuality’ (asexual white-Anglo non-binary Christian, 20s). A bisexual white-Anglo non-binary Christian (20s) said ‘affirming apologetics for queer people. Yes, I think they’re the important things’ alongside discussing gender and sexuality with their psychologist. A bisexual white-Anglo intersex man (40s) said ‘it’s just speaking your truth constantly. Having supportive people around you’. A bisexual white-Anglo evangelical Christian cis-woman (20s) noted the need to ‘talk about common experiences and sitting in the shit-ness’ whilst eventually discussing religious identity aligned with ‘feeling good’. All emphasised discussions enabling positive, affirming intersectional identities over time.

Support and resources

Mental health practitioners should understand survivors’ faith goals

SOGIECE survivors were asked about their experiences of recovery resources and background information that may be useful to professionals looking to support their recovery. Leximancer found three large themes in the focus group responses: health, different and having (). The largest Leximancer-identified theme was ‘health’ (97 hits, 100% relationality to other concepts). This theme focussed on health and mental health practitioners needing to understand survivors’ faiths and individual faith goals (combining the sub-concepts: health, mental, people, understand, support, secular, faith, guess, things, need, able, identity, person, affirming, trauma). Many survivors said their mental health professionals assumed they no longer wanted to be religious; this was inappropriate for those who retained their faith whilst abandoning SOGIECE. A bisexual white-Anglo trans-woman (20s) said her psychiatrist argued ‘being religious was delusional. I never went back to see her’. A asexual white-Anglo non-binary person (20s) respondent commented their psychologist had ‘confusion initially around the fact that I was queer and wanted to be Christian’. A white-Anglo trans-woman (20s) recalled psychologists ‘definitely encouraged (me) to preference my queer identity and my secularised world over my faith, when that was really impossible for me’. A Presbyterian Anglo-Maori gay cis-man (30s) said ‘There’s almost a binary view. (…) rather than embracing the whole spectrum of faith’. He argued that instead, ‘the goal of a good psychologist is to help you to get where you want to be as a healthy person’.

Figure 2. Leximancer themes for SOGIECE survivors’ comments on resources.

Conversely, survivors denounced professionals forcing unwelcome religious views. For example, an Orthodox Coptic Christian cis-man (20s) explained a psychologist attempted a visualisation ‘bringing Jesus back into the picture’. He explained that ‘someone putting God in and Jesus in for me just felt a bit confronting’ given it was not his own goal. One white-Anglo demi-romantic asexual Anglican woman (20s) had a psychologist try to connect her with material ‘suggesting affirming churches’. In her upbringing other faiths were heretic, ‘I’d been raised thinking of this as heresy (…) I’m going, so the only people who validate who I am are the people I’ve been taught aren’t Christians’. For diverse survivors, she explained: ‘It’s like “here’s what I need you to need’, rather than ‘I’m meeting you where you’re at and we can go on together”’.

Different levels of training create different recovery possibilities

The second largest Leximancer-identified theme was ‘different’ (57 hits, 46% relationality to other concepts). This theme focussed on how different approaches could be helpful or unhelpful, and mental health professionals needed to be trained in the possibilities of what individual SOGIECE survivors at different stages needed (combining the sub-concepts: different, trying, experience, helpful, unhelpful, wanted, looking). For example, a Presbyterian Anglo-Maori gay cis-man (30s) described the difficulty of ‘having to go to each (professional) and try and work out, what do I tell them, what do I not tell them? Are (they) supportive or are they not? And I didn’t realise how traumatising that experience is … the difference between people who aren’t trained’. He noted that when a professional was trained in the importance of prompt mental health support turnarounds and general LGBTQA+ supports, it made a large difference: ‘… they called me, they said, we just want to ask you what pronouns you’d like us to use. It’s that rush of, oh, they get it. These are safe people’. Participants described how they wished survivor recovery services had signs or indicators that they were trained in and supportive of LGBTQ+ issues generally.

Several participants discussed the difficulty of having to respond to professionals’ false assumptions or educate them on broader cultural concerns such as being LGBTQA+ allies. One South-East Asian lesbian (30s) noted ‘when you put a minority within a minority and throw the faith stuff in there, a lot of those professionals (…) really have no idea how to help’ (without training). A bisexual white-Anglo trans-woman (20s) said: ‘in getting psychological help, it’s been really difficult and even retraumatising to talk about conversion practices at first, because I literally have to explain everything to the psychologist. They just don’t know what it looks like’. This means that each time she seeks help ‘I literally have to go through my lived experience and kind of be retraumatised (…) to support them to support me’. An asexual white-Anglo queer non-binary Christian (20s) said, ‘I had to explain asexuality, and that ended up being quite, actually, traumatising, because she (…) spent a long time thinking that I wasn’t actually asexual but I’d just had a bad experience’. A bisexual white-Anglo non-binary Christian (20s) explained that professionals need to understand ‘this weird tension as a survivor that you feel of the fact that you chose to go through these practices, but that you also chose to leave. And that both of those choices were your own but that you were being really negatively misinformed’. They explained survivors need to be supported to see (and never shamed for) how their choices were compromised by a lack of exposure to affirming alternatives.

A gay cis-man (30s) also said health and mental health professionals should seize opportunities for supporting people engaged in SOGIECE; without being aggressive in ways that disrespected individuals’ need for control of the process. He explained that in his ‘gung-ho’ efforts to become ‘ex-gay’, he went to see a GP and asked for a prescription to limit his sexual drive. The GP ‘told me he’d got something he could possibly prescribe. It might cause nipples to weep or something. But he was beside himself with concern that I’d been brainwashed’. At the time the participant said ‘I was aghast that someone was against my plan to convert. He was the enemy’. Though he applauds the rural doctor’s effort to stop him, he wished the approach had been gentler so that he didn’t cut contact. When he went for a referral to another GP (perhaps with more training), they took a gentler approach: ‘without a shadow of a doubt, (they) instantly assured me, yes, you can leave here today with a letter. That’s no problem. And then, hey, would you tell me a bit about what’s going on?’ This allowed him to ‘frame it (SOGIECE) naturally and absolutely correctly (…) And that was really helpful’. Contexts of non-judgement of the individual and their timing (though not ‘support for SOGIECE’) supported more opportunities towards recovery.

Participants also wanted professionals to understand SOGIECE myths of causal relationships between childhood trauma and sexual abuse, and being LGBTQA+. One bisexual white-Anglo trans-woman (20s) emphasised ‘Research shows the relationship between them is not causal, but it does interact in that person’s ability to accept themselves’. Finally, a bisexual white-Anglo non-binary Christian (20s) focussed on the need for mental health training programs to enable professionals to work in nuanced ways with dualities. They said ‘I felt this weakness. And being able to have the counsellor actually understand that and acknowledge, yes, but then also say, here’s how you’re strong’ was important, because in the area of conversion survival, ‘there’s a lot of dualities (…) that need to be balanced very carefully. And the times where I’ve felt very unheard and unseen by allies or, I guess, people who are trying to be supportive, is when they can’t acknowledge those dualities’.

Having accessible texts and resources helps

The third largest Leximancer-identified theme was ‘having’ (26 hits, 40% relationality to other concepts). This theme focussed on the value of SOGIECE survivors and mental health professionals having, and sharing, access to a range of resources – particularly texts (combining the sub-concepts: having, psychologist, explain, saying). Survivors argued that pro-SOGIECE texts were unfortunately most accessible in their experiences of religious, educational and psychological institutions and the broader culture. A Presbyterian Anglo-Maori gay cis-man (30s) said ‘The ex-gay stuff was so easy to come up, the conversion therapy stuff was just everywhere’. A Christian gay cis-man (30s) noted a dearth in resources ‘surrounding legislation that’s going on’ – suggesting there may be room for government-funded, official resources. Further, accessing affirming resources was difficult for some people deeply inside SOGIECE contexts, for example a white-Anglo asexual woman (20s) said at her Anglican education setting there were ‘Covenant Eyes’ on their computers. She could only access ‘conversion ideology materials’ and was ‘terrified to look for affirming supporting stuff because the principal (…) looks at everything we do’. She described how ‘secrecy, shame, the surveillance sort of reporting back, all that sort of thing compound(ed) to stop me actually being able to access things’. Such contexts conflated spiritual support with mental health support, thus avoided meeting real mental health needs.

Participants described good experiences with mental health professionals who shared and requested SOGIECE recovery materials. For example, an Orthodox Coptic Christian cis-man (20s) affirmed ‘a really good psychologist who, anytime I’d bring something up or suggest a material she’d be like; great, can you send me through the links?’ (…) then we sort of had common ground’. Survivors who had been exposed to resources discussed the value of a wide range of texts and other resources to their recoveries. An asexual white-Anglo non-binary Christian (20s) said ‘Kevin Garcia has an amazing blog’. A bisexual white-Anglo transgender woman (20s) said good resources included ‘Anything by Brené Brown. The Reformation Project. Kathy Baldock’s book, Walking the Bridgeless Canyon. Two podcasts, one is The Liturgists, the other one is The Bible for Normal People. (…) Matthew Vines’ God and the Gay Christian’. Trans and gender diverse participants repeatedly affirmed an Austen Hartke website as a trans-affirming, womanist, non-Eurocentric resource linked to diverse sources. Other resources included affirming professionals.

Discussion

Ecology of SOGIECE recovery

SOGIECE survivors required support in their re-engagements with their psycho-social development across the Bronfenbrenner model’s systems, to build their autonomy in relationship to self (the Individual including their gender and sexuality development) through more positive engagement with others, institutions and cultures. Opportunities to increase control over their support processes in their Microsystems were core to participants’ healthier social, institutional and cultural development and re-engagements; and recoveries. Participants’ stories showed they most recognised that they needed engagements with affirming people with whom to be freely themselves within both their Microsystems. Potentially these engagements can be with mental health professionals, family, friends and survivor support groups. They also needed reduced surveillance and/or increased affirmation around their gender and sexuality in their Mesosystems; it could thus be useful to have people and supports in their Microsystems who were less inter-connected to other areas of their lives. Thus, the needs of these participants fit the recommendations for community-based and community-building interventions seen in broader research (Horner, Citation2019; Lutes & McDonough, Citation2012; Maccio, Citation2011).

However, survivors’ stories emphasised that it was especially important that their Microsystem recovery supports (family, faith groups and mental health practitioners) did not compromise their re-engagement with their development of autonomy at the Individual level. The data highlighted participants’ resistance to mental health practitioners’ attempts to control timing or choices in recovery efforts. (Re)development of an individual survivor’s autonomy should be viewed as a sensitised issue at the core of Bronfenbrenner’s model and any plan for their recovery, to be primarised for survivors whose past experiences of (SOGIECE) ‘therapy’ and key Microsystem influences was repressive and coercive. It is especially important for survivors to develop autonomy in the conceptualisation of their own religious goals, and in influencing mental health practitioners’ support plans. This concern for Australian survivors echoes the US-based warning to mental health professionals against encouraging the maintenance or return of survivors’ past conformity-drives around social or community structures in community-based recovery work (Haldeman, Citation2002); which should also be extended to include a warning against conformity with the therapists’ own faith (or faith-negative/faith-positive) goals and communities.

Social supports for Australian survivors in this study were especially complicated by any false assumption that LGBTQA+ identities and religious identities could not co-exist regardless of what the specific (LGBTQA+ and religious) identities were; such assumptions should be addressed in training for mental health professionals. This was not a bias in the sample; participants exposed to SOGIECE are significantly more likely to come from religious backgrounds or be religious (Jones et al., Citation2021). There also especially appeared to be a lack in education for mental health professionals on asexuality as a ‘genuine’ identity (not a result of repressed or damaged attraction) – professionals need to avoid adding to existing SOGIECE narratives on this identity. Sometimes survivors needed time away from segments of their Microsystems and Mesosystems if and where SOGIECE-focussed religious communities dominated these systems; or needed a break from a particular version or aspect of faith, or faith itself. But they needed to be the determining party in such goals in order to enhance recovery from SOGIECE. Foregrounding this autonomy and sense of taking back control over one’s life and therapy, especially considering past therapy would potentially have been externally led, could be added to the core special considerations for SOGIECE survivors in treatment, alongside themes like distinguishing ‘pathology’ from ‘negative effects’ of SOGIECE promoted in US research (Horner, Citation2019).

A distinct finding of the study was that survivors needed considerable time for support to be effective, regardless of whether their SOGIECE experience was around gender or sexuality; however the Chronosystem (time) needs to be engaged with constructively. It was important to do developmental work discussing and reconciling dualities across their identities and beliefs with various parties in the Micro and Mesosystems, including professionals. It was also important to draw on broader constructions of LGBTQA+ identity, relationships and discrimination from the Macrosystem of Australian culture beyond survivors’ existing Microsystems – which were often closed off from social acceptance of the ideas behind marriage equality, anti-discrimination legislation and other cultural artefacts that could be used to reality-test the de-valuing of LGBTQA+ identities. Creating recognition of this needed time for change within the Exosystem of social welfare provisions and policies could be a useful next step.

Survivors outlined a range of resources and supports that were helpful, and pointed to modes of support that could be problematic such as setting goals for survivors with which they did not agree. Specifically, they promoted professionals understanding survivors’ faith goals rather than imposing any; seeking training on faiths and SOGIECE; and sharing where possible (but not pushing) accessibility of a range of texts and other resources that may match the survivor’s needs and personal goals (without promoting or endorsing SOGIECE itself). Intersectional narrative exploration (e.g., Hammoud-Beckett, Citation2007) may be especially useful in therapy navigating concerns over cultural and religious discrimination during SOGIECE recovery.

The study was limited in including only SOGIECE survivors; not those who currently hold ex-gay or ex-trans identities – due to the aim of understanding recovery processes. Thus, the views of those who see no need for recovery, only appeared through current survivors’ recollections. In these data, it was notable that participants reflected that mental health professionals lose clients by directly negating SOGIECE, but that nonetheless SOGIECE should never be affirmed. Similarly, though changes in denominations or orthodoxy levels for religious SOGIECE survivors were common, it was notable that participants did not want mental health professionals to lead such changes. Instead it was useful for mental health professionals to build relationships over time supporting the client first with the problems they present with, and then work towards eventually supporting individuals’ broadened exposures to affirming possibilities around LGBTQA+ identities closer to or within their own faith goals and Microsystem cultures. Recovery approaches and visions closer to their initial identities were more important in the initial stages, so clients can question the usefulness of SOGIECE without feeling forced into identities or sections of Micro- and Macro-systems too far from their current or ideal positionings.

However, once individuals were certain in seeking to recover from SOGIECE, support approaches and resources could, and might need to, broaden and vary (with sensitivity to whether or how individuals’ faith goals may or may not evolve). It could be both useful for a committed survivor to access communities that related to their specific (gender, sexuality, and/or religious) identities (such as gay Christian groups); but also to access more general peer support groups and written supports too which were more varied (for example, an asexual Christian’s recovery may still benefit from reading material about a gay Jew’s recovery; and many participants later accessed mixed support groups). Whilst many studies show SOGIECE does not work (APA, Citation2009), this study conversely captured the usefulness of a wide variety of supports in recovery from SOGIECE itself, however participants suggested SOGIECE recovery resources were less widespread than resources promoting SOGIECE. This small study was limited in testing this claim.

Conclusion

In conclusion, mental health practitioners should understand SOGIECE survivors need recovery pathways that consider complexities at all levels of their ecology of development; and diversify their exposures to affirming supports and ideas at all levels. Initially for people undergoing, and/or also questioning SOGIECE, who are unsure about choosing recovery from SOGIECE, it appeared more useful for mental health professionals to focus on relationship building and alternative sources of information about LGBTQA+ identities that were not too contrasting with their existing positionality. Over time, it can be possible to provide a wider range of supports and ideas. However, at all stages, the autonomous religious and LGBTQA+ identity goals of individual survivors should be foregrounded in recovery supports; as well as in the therapy itself given survivors’ background experiences may include directly abusive therapy dynamics. Larger scale statistical studies directly on the usefulness of different therapy types might be useful for SOGIECE survivors. Following the suggestion from participants that SOGIECE resources might be more widespread than recovery resources, mental health researchers could also conduct quantitative and qualitative studies directly mapping and comparing SOGIECE and SOGIECE recovery resources and their accessibility.

Acknowledgements

Contributions to this study were made by a SOGIECE survivors reference group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data is not available open access due to ethical and safety concerns for participants, whose transcripts may be identifiable within their communities if shared in full.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Melbourne-based LGBTQA+ conversion survivor support and advocacy group.

2. White-Anglo indicates participants with backgrounds from the British Isles.

References

- ACT Minister for Social Inclusion and Equality, & ACT Minister for Justice Consumer Affairs and Road Safety. (2020). Sexuality and Gender identity conversion practices bill 2020. ACT Government.

- American Psychological Association. (2009). Report of the task force on appropriate therapeutic responses to sexual orientation.

- Australian Psychological Society. (2010). Ethical guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay and bisexual clients.

- Beckstead, A. L. (2020). Can we change sexual orientation? Archives of Sexual Behaviour, 41(1), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9922-x

- Bishop, A. (2019). Harmful treatment. Outright Action International.

- Blosnich, J., Henderson, E., Coulter, R., Goldbach, J., & Meyer, I. (2020). Sexual orientation change efforts, adverse childhood experiences, and suicide ideation and attempt among sexual minority adults, United States, 2016-2018. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), E1–1030. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305637

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Crouter, A. (1986). The evolution of environmental models in developmental research. In P. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 357–414). John Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6696

- Burns, M. (2011). School psychology research. School Psychology Review, 40(1), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2011.12087732

- Charmaz, K., & Bryant, A. (2011). Grounded theory and credibility. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 291–309). Sage.

- Cretchley, J., Rooney, D., & Gallois, C. (2010). Mapping a 40-year history with Leximancer. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(3), 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110366105

- Csabs, C., Despott, N., Morel, B., Brodel, A., & Johnson, R. (2020). SOGIEC survivor statement. Brave.

- Davis, G. (2015). Contesting intersex. NYU Press.

- Erzen, T. (2006). Straight to jesus. UCP. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520939059

- Farrelly, C., O’Brien, M., & Prain, V. (2007). The discourses of sexuality in curriculum documents on sexuality education. Sex Education, 7(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810601134801

- Flentje, A., Heck, N., & Cochran, B. (2013). Sexual reorientation therapy interventions: Perspectives of ex-ex-gay individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 17(3), 256–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2013.773268

- Flentje, A., Heck, N., & Cochran, B. (2014). Experiences of ex-ex-gay individuals in sexual reorientation therapy: Reasons for seeking treatment, perceived helpfulness and harmfulness of treatment, and post-treatment identification. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(9), 1242–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.926763

- Goldberg, A. (2014). Lesbian, gay and heterosexual adoptive parents’ experiences in preschool environments. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(1), 669–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.07.008

- Green, A., Price-Feeney, M., Dorison, S., & Pick, C. (2020). Self-reported conversion efforts and suicidality among US LGBTQ youths and young adults, 2018. American Journal of Public Health, 110(8), 1221–1227. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305701

- Haldeman, D. (2002). Therapeutic antidotes: Helping gay and bisexual men recover from conversion therapies. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy, 5(3), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J236v05n03_08

- Hammoud-Beckett, S. (2007). Azima ila hayayti: An Invitation to my life. International Journal of Narrative Therapy and Community Work, 1(1), 29–40.

- Horner, J. (2019). Undoing the damage: Working with LGBT clients in post-conversion therapy. Columbia Social Work Review, 1(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-8xxa-aq93

- Hurren, K. (2020). Ending efforts to change sexual orientation, gender identity & gender expression. Community-based research centre.

- Jones, T. (2015). Policy and gay, lesbian, transgender, intersex and queer students. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11991-5

- Jones, T. (2020). A student-centred sociology of education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36863-0

- Jones, T., Power, J., Hill, A. O., Despott, N., Carmen, M., Jones, T. W., Anderson, J., & Bourne, A. (2021). Religious conversion practices and LGBTQA+. Youth.

- Lutes, J., & McDonough, M. (2012). Helping individuals and families recover from sexual orientation change efforts and heterosexism. In J. Bigner & J. Wetchler (Eds.), Handbook of LGBT-affirmative couple and family therapy (pp. 443–458). Routledge.

- Maccio, E. (2011). Self-reported sexual orientation and identity before and after sexual reorientation therapy. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 15(3), 242–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2010.544186

- Mallory, C., Brown, T., & Conron, K. (2019). Conversion therapy and LGBT youth. Williams Institute.

- Ozanne Foundation. (2020). ’Conversion therapy’ & gender identity survey.

- Queensland Government. (2020). Health legislation amendment bill 2019.

- Salway, T., Ferlatte, O., Gesink, D., & Lachowsky, N. (2020). Prevalence of exposure to sexual orientation change efforts and associated sociodemographic characteristics and psychosocial health outcomes among Canadian sexual minority men. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(7), 502-509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720902629

- Schlosz, D. (2020). The impact of reparative therapy on gay identity development. University of Texas.

- Serovich, J., Craft, S., Toviessi, P., Gangamma, R., McDowell, T., & Grafsky, E. (2008). A systematic review of the research base on sexual reorientation therapies. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00065.x

- Smith, A., & Humphreys, M. (2006). Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behavior Research Methods, 38(2), 262–279. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192778

- UK Government Equalities Office. (2018). National LGBTQA+ survey. UK Government.

- UK Government Equalities Office. (2021). Conversion therapy: An evidence assessment and qualitative study. UK Government.

- United Nations. (2020). Report on conversion therapy.

- Waidzunas, T. (2015). The straight line. University of Minnesota Press.