ABSTRACT

Objective

Competency-based assessment on placement ideally involves evaluation of a trainee performing clinical skills using fit-for-purpose tools that are simple for clinical supervisors to use and informative to the trainee. The current study examined the potential utility of a new tool, the Psychology Competency Evaluation Tool – Summative (PsyCET-S), designed to assess the attainment of professional competencies in clinical psychology trainees.

Method

Twelve experts tested the inter-rater reliability of the vignette ordering, before the tool was used to assess performance of clinical psychology trainees on placement by both supervisors and trainees. Ninety-nine placement reviews of 45 trainees at different stages of training were analysed.

Results

Strong inter-rater reliability in the rank ordering of vignettes within each domain indicated their ability to capture competence development. Supervisor and trainee ratings showed a gradual increase in competence from early to later stages of training in all domains, with performance plateauing for the final placement. Evidence of both the leniency bias and halo effect were evident, with supervisors appearing more lenient than the trainees themselves.

Conclusion

The PsyCET-S encourages supervisors to evaluate the development of professional competencies in their trainees in a way that can optimise trainee learning and future practice as a Psychologist.

Key Points

What is already known about this topic:

Board-approved supervisors of professional psychology trainees are required to “effectively monitor, assess and evaluate the competencies of a supervisee”, yet simple and effective methods for how to do this are limited.

Effective competency-based assessment can optimise students’ learning and is essential to regulating the profession.

Tools that measure the performance of clinical skills and their development over time are needed.

What this topic adds:

We present a new evaluation tool that describes expected student performance of professional competencies on placement at the beginning of clinical training through to entry-to-practice that is designed to capture both supervisor and trainee ratings.

Data from 99 placement reviews indicate that the tool captures the progression of competency attainment over time from both the trainee and supervisor perspective.

The tool provides trainees with meaningful feedback on their competency development while preserving the normative function of supervision.

Supervised placements are an essential component of professional psychology training where trainees acquire the necessary skills for the effective provision of clinical services (Nicholson Perry et al., Citation2017). There is broad agreement that assessing for competency attainment is better for the student’s learning, and more effective at upholding standards for public safety, than counting hours of teaching or placement experiences (Epstein & Hundert, Citation2002; Gonsalvez, Shafranske, et al., Citation2021; Pachana et al., Citation2011). Clinical supervisors are integral to this process as they monitor the trainee’s competencies, encourage the trainee’s self-reflectivity, and provide effective feedback to the support trainee development towards professional registration (Holloway, Citation2012; Psychology Board of Australia, Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2011). The Psychology Board of Australia (PsyBA) has determined the core competencies required for general registration as a Psychologist, as well as specific competencies for nine different Areas of Practice Endorsements (AoPEs) that reflect international standards (Gonsalvez, Shafranske, et al., Citation2021; Psychology Board of Australia, Citation2019). Of note, PsyBA is currently revising the general registration competencies to improve alignment with best practice competency assessment and the needs of the community (Psychology Board of Australia, Citation2023). These professional competencies (existing and drafted) provide a set of benchmarks that describe the knowledge, skills, attitudes, behaviours, values and other attributes that are needed to perform safely and effectively as a psychologist. However, methods for how supervisors might track and evaluate the development of professional competencies are scarce (Barrett et al., Citation2020; O’Donovan et al., Citation2011).

Competency evaluation rating forms (CERFs) are commonly used to review a trainee’s knowledge and performance of clinical skills on placement. CERFs typically require supervisors to rate their trainees on different competencies on a Likert scale (e.g., At-, Above-, or Below-expected levels) and this is used to guide whether the trainee has shown sufficient competence to successfully pass their placement (Kaslow et al., Citation2009; Scott et al., Citation2011). CERFs are easy to use and can reflect multiple competencies (Kaslow et al., Citation2009) but are vulnerable to systematic rating biases that can compromise the objectivity and usefulness of the evaluation. For example, clinical supervisors tend to rate their trainees’ performance favourably (i.e., leniency bias), rarely assigning below average grades (Gonsalvez & Freestone, Citation2007). A recent, multisite study involving nine training institutions showed that placement supervisors were inclined to pass their placement student overall even when they received scores considered to be “below competency thresholds” during the placement (Gonsalvez, Terry, et al., Citation2021). Lenient ratings are likely driven by the supervisor’s role in being supportive and encouraging of the trainee, but doing so undermines the normative function of supervision and can lead to trainees’ overestimating their competence (O’Donovan et al., Citation2011; Terry et al., Citation2017) or failure to fail underperforming trainees (Dudek et al., Citation2005; Gonsalvez, Terry, et al., Citation2021). Further, clinical supervisors often form a global impression of the trainee that is applied consistently across all domains of competence – an occurrence known as the halo effect (Wolf, Citation2015). This leads to a lack of differentiation of specific competencies and clarity around the trainees’ strengths or areas for development and is inconsistent with findings that competencies can develop at different rates (Deane et al., Citation2018).

Attempts have been made to help supervisors reach a more objective evaluation of trainees on placement by adding behavioural anchors to competency assessment tools. For example, Gonsalvez et al. (Citation2013) developed the Clinical Psychology Practicum Competencies Rating Scale (CΨPRS) to describe four stages of student performance from beginner to competent that are applied to different domains of clinical competencies. The researchers found that more detailed vignettes that described each clinical competency across developmental stages helped to reduce leniency and halo biases. However, this approach is potentially burdensome with supervisors required to compare trainee performance against 45 vignettes across 10 broad domains of clinical competence. The instrument is also based on a broader conceptual framework of clinical competency (Hatcher & Lassiter, Citation2007) rather than the professional competencies as defined by the national regulator (Psychology Board of Australia, Citation2019) and which need to be demonstrated in order to be registered. Rice et al. (Citation2022) developed a tool that includes Level 3 professional psychology competencies as defined by the Australian Psychology Accreditation Council which are certainly reflective of the PsyBA standards but not synthesised into vignettes. Instead, a general competency scale is provided to supervisors and trainees to rate 81 individual items. Remarkably, there are no validated tools with behavioural vignettes that describe the currently approved PsyBA professional competencies for general registration as a Psychologist or AoPEs during professional psychology training.

An assessment tool that reflects the developmental trajectory of PsyBA core competencies can also directly enhance the trainee’s knowledge of their professional responsibilities and learning needs (Gonsalvez, Shafranske, et al., Citation2021; van der Vleuten et al., Citation2012). Hitzeman et al. (Citation2020) confirmed that psychology trainees are reasonably accurate when self-assessing their performance of clinical competencies against the expert opinion of their clinical supervisor. Having a trainee and their supervisor collaboratively evaluate where the student is up to in their learning, where they are going, and what needs to be done to get them there and can help the trainee construct meaningful learning plans (Black & Wiliam, Citation2009). Notably, engaging in self-assessment also fosters self-reflection practices – another essential attribute to being a competent clinician (Rodolfa et al., Citation2005). The developmental trajectory of trainee self-assessment of PsyBA competencies specifically, in concordance or discordance with supervisor evaluations, across supervised placement in clinical psychology training, deserves further attention.

In this paper, we describe the development and preliminary evaluation of a new CERF-type tool, that is relatively brief to complete, reflective of six currently approved PsyBA domains of competency for general registration and clinical psychology AoPE specifically, and uses behavioural anchors to improve the objectivity of ratings (Gonsalvez et al., Citation2013; Popham, Citation1997). The tool, named the Psychology Competency Evaluation Tool-Summative (PsyCET-S), requires supervisors to rate trainees in seven core domains of competence on a scale that is anchored by behavioural vignettes (i.e., a description of what a supervisor might observe the trainee doing in practice or in supervision) as they might evolve during postgraduate training, including the registrar years that are intended to hone clinical competencies for AoPE in clinical psychology. The incorporation of behavioural vignettes provides trainees with a clear understanding of the skills and behaviours required in order to demonstrate competence within each domain, allows progress to be monitored over time, and concrete learning plans can be developed across placements or registrar positions (Black & Wiliam, Citation2009; Gonsalvez et al., Citation2013; van der Vleuten et al., Citation2012). The current study used expert agreement to explore the reliability of the tool. The performance of the tool was examined in a cohort of clinical psychology trainees undertaking internal and external placements at different stages of their doctoral training (that reflected the 5th and 6th year of psychology training and the beginning of a registrar program towards AoPE in clinical psychology). It was hypothesised that the PsyCET-S would capture the development of core clinical psychology competencies over time and reduce potential rater biases (i.e., leniency/halo biases).

Method

Design

Ethics approval was provided by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (validation study approval number 2260, pilot study approval number 9547). Following the development of the PsyCET-S tool, its reliability was assessed, and then the performance of the tool was evaluated in a cohort of clinical psychology trainees.

Development of the PsyCET-S

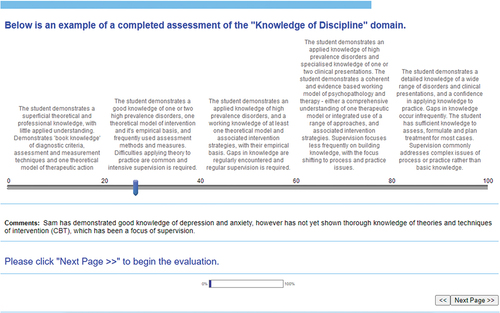

The PsyCET-S was designed to be used on clinical psychology placements to assess trainee competence across six core domains set out by the PsyBA (Psychology Board of Australia, Citation2019) along with the domain of reflective practice given its importance to clinical competence (Rodolfa et al., Citation2005). Using the Qualtrics platform to administer the tool, supervisors (and trainees) rate the degree of competency attainment in each of the seven domains by moving an electronic slider on a continuous 0–100 visual analogue scale separated into 20-point bands. Each band was anchored by a behavioural vignette that described the knowledge, skills, and behaviour expected to develop over the course of clinical training, with 0–20 reflective of a beginner trainee with preliminary knowledge of the discipline and limited clinical skills, and 80–100 reflective of a trainee at the end of their professional doctorate program or first year of their clinical registrar program following a masters program. Raters were instructed to review each of the five vignettes in a given domain and identify the one that best matched the competence level of the trainee and to place the slider within that scoring band to the degree they had attained the knowledge and skills listed in the vignette. For example, to use the higher end of the scoring band if they had attained all of the knowledge and skills of a given vignette, and more towards the lower end of that vignette section if some but not all knowledge and skills had been attained (see for an example section of PsyCET-S). Supervisors could add comments after rating each competence domain, and at the end of the tool where supervisors could list strengths, future learning goals, and an overall recommendation regarding placement outcome (satisfactory, borderline satisfactory, unsatisfactory).

Authors KL and KT developed the behavioural vignettes in order to reflect the expected trajectory of competency development over the course of clinical psychology training. The vignettes were based on a) review of literature of competency standards and b) the authors' experience in supervising and assessing clinical psychology trainees. Vignettes varied in terms of breadth or depth of knowledge, fluency, or sophistication of demonstrated skills, level of professionalism, and/or autonomy. For example, within the Psychological Assessment domain, the behavioural vignette at the lowest level (1–20 band) was: “The trainee demonstrates knowledge of assessment techniques and measures including clinical interviews, behavioural observation, mental status exams and major standardised psychological tests, but has not yet developed skills in using these techniques and measures”, and progressed up to the highest level (81–100 band) with: “The trainee demonstrates a breadth of knowledge of assessment techniques and measures, including clinical interviews, MSEs, tests and observations, and shows skilled use of a variety of techniques. Knowledge of specialised tests for particular clinical problems or populations, and sophisticated interpretation may be demonstrated. Trainees can independently develop effective clinical formulations. Reports are informed, succinct, valid and well organised”.

Reliability of the PsyCET-S

A key feature of the PsyCET-S is the use of behavioural vignettes to reflect different levels of competence attainment. To ensure the appropriateness of the ordering of the vignettes in each domain in the PsyCET-S, we examined inter-rater reliability for vignette order in a sample of placement supervisors. Supervisor participants were recruited through our Australian-based university doctoral training program and were required to have a) general registration as a Psychologist, with an AoPE in clinical psychology with PsyBA and 2) be a Board-approved supervisor of psychology trainees enrolled in a higher degree program. Participants were sent a survey in which they were asked to rank in order the five behavioural vignettes in each competence domain from least to most competent. The vignettes were presented in a random order within each domain. They were also asked to rate each behavioural vignette on the 0–100-point competency scale to assess the spread of scores across the scale. At the end of the survey, panel members could provide additional suggestions and comments regarding the vignettes including their understandability and usefulness. If supervisors did not show strong agreement in the rank-ordering of the vignettes, we planned to modify the vignettes based on supervisor comments and author review, and repeat the rank-ordering survey until agreement had been reached (see Data Analysis section for agreement criteria).

Performance of the PsyCET-S in clinical psychology trainees

Following the development and reliability analysis, the use of the PsyCET-S tool for assessing competence was examined in clinical psychology trainees. The performance of PsyCET-S was examined in terms of its ability to capture the development of trainee competence across placements, different trajectories for different domains, moderation of leniency and halo effects, and comparison of supervisor and trainee ratings. Data from the end of placement reviews using the PsyCET-S were examined for trainees in a doctoral-level program in Australia from March 2014 – September 2017 (See Supplemental Online Materials for PsyCET-S tool downloaded from the Qualtrics survey platform). In this doctoral program, trainees complete four clinical placements for 40–60 days each, with completion of their third placement reflective of a Masters level of training, and the fourth placement viewed as an internship akin to the first year of the registrar program. Their first placement was located in the university psychology clinic, while subsequent placements were in a range of external settings, primarily in public mental health. For the end of the placement review, both the supervisor and trainee completed the PsyCET-S, and the results were discussed in a meeting led by the supervisor. Training in how to use the PsyCET-S was provided to placement supervisors and trainees by the placement coordinator (an experienced Clinical Psychologist and supervisor).

Data analysis

To establish the inter-rater reliability of the vignette ordering, Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance (W) was used to establish the inter-rater agreement of supervisors in ordering the vignettes with W scores of 0–.20 = no level of agreement, .21–.39 = minimal, .40–.59 = weak, .60–.79 = moderate, .80–.90 = strong, and above .90 = almost perfect level of agreement (McHugh, Citation2012). A pre-determined goal was to achieve a minimum of 0.90 agreement for each competence domain. The range of vignette ratings on the 100-point scale were used to assess the spread of scores.

To examine the performance of the PsyCET-S in trainees, we first examined descriptive data to establish the ability of the tool to track change in competency scores across placements. Paired sample t-tests were used to assess whether supervisor and trainee competence ratings improved over successive placements within each competence domain (i.e., 1st to 2nd placement, 2nd to 3rd, and 3rd to 4th). To examine whether supervisors differentiated trainee competencies or instead were prone to halo biases (i.e., rating competence more globally), paired sample t-tests with Bonferroni adjustment were used to examine for mean within subject differences between each of the seven competence domains at the first and last placements. Leniency bias in ratings was examined descriptively using the percentage of scores at the upper 51–100 end of the scale, and also by comparing mean scores relative to the expected level at each stage of placement (e.g., a score of 20 was expected by the end of the first placement).

Results

Reliability of the PsyCET-S

Twelve supervisors participated in the reliability analysis. Mean years of experience in supervising clinical psychology trainees were 5.0 years (range = 1.5–10.0 yrs), with supervisors primarily working in public mental health settings (11/12) with adult populations (5/12), child/adolescent (6/12) or both (1/12).

Supervisors showed high degrees of interrater reliability in ranking the order of the initially developed behavioural vignettes, with Kendall’s W values all above 0.90 apart from the Research (Kendall’s W = .649) and Interpersonal (Kendall’s W = .839) domains. The vignettes for these two domains were revised by the authors and reviewed by six of the original clinical psychologist supervisors (Mean experience = 3.5 years, range = 2.0–6.0 years): this found perfect agreement for ordering of the revised behavioural vignettes. displays the agreement ratings and means/ranges for each domain. There was a good range of scores in each domain.

Table 1. Interrater agreement between experts (N = 12) in ordering the five behavioural vignettes in each domain.

Performance of the PsyCET-S

Data on the PsyCET-S end of placement review were available for 45 clinical psychology trainees between March 2014 and March 2017. Descriptive statistics for the supervisor and trainee ratings for the seven competency domains (across all placement levels) are presented for in . Data were examined separately for supervisor ratings and trainee self-ratings.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for supervisor and trainee ratings on the PsyCET-S for each competence domain.

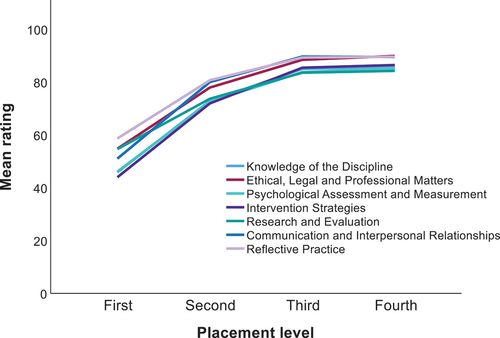

Supervisor ratings

There were a total of 99 placement review forms for the 45 trainees rated by 46 different supervisors. Of the 99 reviews, 27 were for the first placement, 21 for the second placement, 28 for the third, 23 for the fourth placement. There are signs of leniency bias in ratings with all domains having more than 70% of scores in the upper half of the scale (i.e., 51–100) and means ranging from 77.8 for Knowledge to 87.8 for Reflective Practice despite almost half of the placement reviews being from the first two placements of training in which scores of <50 would be expected.

shows supervisor ratings on the PsyCET-S across each of the four placements. This highlights that the leniency bias is most evident at the first placement where average scores were in the 40–60 band, indicating that supervisors were generally not rating students at the level of the first or second of the five behavioural vignettes which were tied to scores of 20 and 40, respectively.

In relation to our primary aim, indicates that the PsyCET-S supervisor ratings show an increase over successive placements, with some plateauing at the end of training between the third and fourth placement. This pattern was confirmed using t-tests as shown in . For each competence domain, supervisor ratings increased from the first to second placement, second to third placement, but there was no difference in ratings from the third to fourth placement.

Table 3. Changes in supervisor ratings on PsyCET-S between successive placements.

In relation to our examination of whether supervisors differentiate between competencies or are prone to halo bias, also indicates some differentiation of competency ratings with Ethics and Reflective Practice competencies rated the highest, while Assessment and Intervention competencies the lowest. Within subject differences in domain ratings were more prominent at the first placement (i.e., less halo effect) compared to the last placement. Mean comparisons provided some support for these patterns (see Supplemental Online Materials, Tables A and B). At the first placement, Assessment, Intervention, and Knowledge competencies had significantly lower ratings than Ethics (all p < .05), Reflective (all p < .05), as well as Research (all p < .05). At the last placement, the patterns were similar but most of the differences were no longer statistically significant, and the Research domain had a drop relative to other domains such that it had lower ratings than the Communication and Reflective domains (both p < .05).

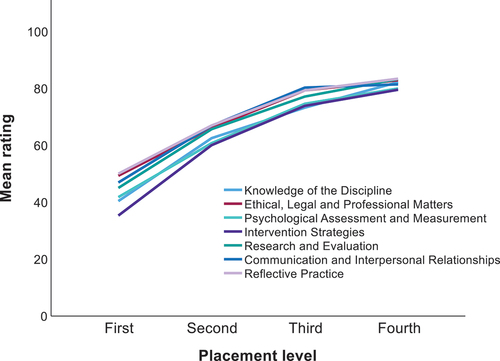

Trainee ratings

There were relatively fewer trainees who completed self-ratings on the PsyCET-S compared to their supervisor’s ratings, with self-rated data available for 64 placement reviews across 32 different trainees, with 22 completed at the first placement, 19 at the second placement, 13 at the third, and 10 at the fourth placement. Comparing data in shows that the mean self-ratings of trainees are considerably lower than of supervisors, generally at least 10 points lower in each domain. In keeping with less leniency bias, only 4/7 domains had more than 70% of scores in the upper half of the scale (i.e., 51–100) for trainee self-ratings.

shows the averaged self-ratings of trainees across domains at each placement level. The trajectory of ratings is similar to that of the supervisors with a gradual increase in competence ratings over placement levels and some tapering on the final placement although less obvious than in the supervisor ratings.

Analyses, shown in largely confirmed this pattern with trainee self-ratings in each domain increasing from the first to second placement, and second to third placement. While 3/7 domains showed no significant difference between the third and fourth placement (all p > .05), trainee self-ratings did increase between these placements in the domains of Knowledge and Research (both p < .01), and there was a trend of increased ratings in Intervention and Reflective Practice domains (p < .1).

Table 4. Changes in trainee self-ratings on PsyCET-S between successive placements.

As was observed for supervisors, differentiation of competencies was more apparent at the first placement compared to the last placement. Analyses (for full details, see Supplemental Online Materials, Tables C and D) showed that at the first placement, trainees gave the lowest ratings for Intervention skills which were significantly lower compared to Ethics, Reflective Practice, and Communication Skills (all p < .05). The Knowledge competency was also given lower ratings than both Ethics and Reflective Practice (both p < .05), while Assessment skills had lower ratings than Reflective Practice (p < .05). At the last placement, there was very little differentiation of competencies as rated by trainees, and there were no statistical differences between domains (all p > .05).

Discussion

This study aimed to develop and pilot a new tool – the PsyCET-S, for capturing core competencies for clinical psychology trainees at key stages of training prior to their registration as a psychologist and future endorsement in clinical psychology. A key feature of this tool was the use of behavioural vignettes to guide competency ratings, and by having vignettes ordered in terms of increasing competence in order to capture trainee development over time. Supervisors of clinical psychology trainees were asked to rank order the vignettes and were found to have strong agreement with each other in the proposed ordering of vignettes for 5/7 domains. For the remaining two domains which showed less agreement (Research and Evaluation and Communication and Interpersonal Relationships), the vignettes were modified, with subsequent review by supervisors, and showed very strong agreement in vignette ordering. These findings support the reliability of the PsyCET-S vignettes in their ability to capture competence development in core areas of practice for clinical psychology trainees.

The tool was also able to capture the development of competencies over stages of training, from both the supervisor and trainee perspectives, in a pilot sample of clinical psychology trainees. This contrasts with many traditional CERFs which involve ratings methods such as whether competencies are “At expected levels” and which provide no details of how competencies are developing across placements. These methods rely on individual supervisors having similar concepts of what is expected of trainees at various stages of training. By having behavioural vignettes of increasing complexity, the skills and behaviours required across training are made explicit and consistent across supervisors. This allows tracking of competence development across placements and it is also clear what skills and behaviours are required for further development (i.e., higher level vignettes). This helps both supervisors and trainees to identify gaps and to establish future training goals (O’Donovan et al., Citation2011; Wiliam & Thompson, Citation2007).

While the PsyCET-S generally captured competence development across placements, there was a plateau in ratings between the third and fourth placements. It is possible that this reflects a failure in the higher order vignettes to adequately capture change; however, it may also reflect that minimal change in competence is observed in the final placement of this clinical psychology training as these skills stabilise. Indeed, other work has also shown that some competencies plateau towards the end of training (Deane et al., Citation2018; Larkin & Morris, Citation2015). There was some discrepancy between supervisor and trainee ratings, with the latter rating some change between the third and final placement, albeit only significantly in two domains: Research and Evaluation and Knowledge of the Discipline. Of note, the point at which competencies plateaued (i.e., third placement) is equivalent to the completion of Masters-level clinical psychology training in terms of placement hours. This suggests that the internship year (within a professional doctorate program) or initial registrar year is an opportunity for supervisors and trainees to monitor competence stabilisation; however, this requires empirical support. Examination of the PsyCET-S in registrars post university training would help to establish the sensitivity of the tool to later stages of development.

A key aim of adding the behavioural vignettes was to reduce known biases in supervisor ratings of trainees. The leniency bias reflects the tendency of supervisors to avoid below average ratings due to the potential impact on the supervisor relationship (O’Donovan et al., Citation2011), the need to justify their low ratings (Gonsalvez et al., Citation2013) or lack of familiarity with assessment tool (Dudek et al., Citation2005). In the development stage, supervisors indicated a willingness to use the lower half of the PsyCET-S scale to rate lower order vignettes; however, in our pilot sample of clinical psychology trainees, supervisors remained hesitant to assign ratings in the lower half of the scale, even though it might be expected that beginning trainees would only be meeting the standards of the second vignette in each domain (i.e., score ≤ 40). This contrasts with other research which has found behavioural vignettes do reduce the leniency bias (e.g., Gonsalvez et al., Citation2013) and may suggest that the lowest order vignettes on the PsyCET-S are too “low level” and that even beginner trainees would be functioning above this level at the end of their first placement. Formal evaluation of the content of the vignettes with experienced supervisors would help to examine this possibility. Alternatively, it may reflect inadequate training for supervisors in using the PsyCET-S and the guidance to use the full extent of the rating scale. Supervisor training in the use of competency rating scales has been shown to combat the leniency bias (Terry et al., Citation2017). Of note, supervisor ratings were more lenient than the trainees themselves.

Our pilot data on the PsyCET-S revealed that both supervisors and trainees were able to differentiate performance between domains of competence at the first placement but less so at the last placement. While this may reflect greater variability in the vignettes at the first and last placements on this tool, it may also suggest that halo effects may be less of an issue at the beginning of placements and supports the use of the inclusion of behavioural vignettes to reduce halo bias as shown in other work (Gonsalvez et al., Citation2013). In the case of our sample, supervisors rated a group of domains that included Knowledge of Discipline, Psychological Assessment and Measurement, and Intervention strategies, lower than the group of Ethical, Legal and Professional Matters, Research and Evaluation, Communication and Interpersonal relationships, and Reflective Practice. These findings are consistent with other research showing that functional competencies (e.g., assessment and intervention skills) are attained later in training compared to foundational competencies such as professionalism and interpersonal skills that trainees already possess upon admission to a postgraduate program (Larkin & Morris, Citation2015). Further, the increased consistency in levels of competence across domains by last placement may be a genuine reflection of competence attainment in this group, rather than an artefact of the tool or rater-bias per se. Achieving consistent and high competence in each domain is the explicit goal of supervised practice and the desired outcome of training well-rounded psychologists who are genuinely competent in all required domains for registration.

Limitations and future directions

The development phase was limited to obtaining supervisor agreement on the ordering of the behavioural vignettes in the PsyCET-S given the key aim of developing a sequence of vignettes that tracks competence attainment over time. Participant supervisors were able to provide comments about the vignettes, but our study did not formally evaluate the content and clarity of each vignette, or examine its reliability such as inter-rater agreement when using the tool. In addition, the five anchoring vignettes were presented at equal intervals on a visual analogue scale without empirical justification. It is possible that the greater variability in domain mean scores observed in earlier placements compared to later placements is due to differential variability between the seven anchoring vignettes (i.e., the seven anchoring vignettes at the 20 mark are vary more widely than those at the 80 mark). Further, the apparent plateau in performance between the third and fourth placements might be explained by greater similarity between the last two vignettes, than between the earlier vignettes, for example. These issues require further exploration to refine and strengthen the psychometric properties of the PsyCET-S.

Examination of performance of the PsyCET-S was limited to a pilot sample of 45 clinical psychology trainees from one university doctoral program. Further analysis using a larger sample and from a range of psychology training programs is recommended to fully evaluate performance of the tool. This should also include the calculation of a reliable change statistic to provide indicators of meaningful change in competency across placements. However, this initial evaluation does highlight the potential strengths of the tool, in particular its capacity to operationalise the skills and behaviours required to demonstrate competent practice in core practice domains (i.e., vignettes) and the ability to track the development of trainee competence over time with sequentially ordered vignettes. This study has also identified potential limitations of the PsyCET-S, such as its susceptibility to leniency rating bias in earlier placements. Future work can investigate whether additional training in using the PsyCET-S can reduce leniency and other biases.

The current study demonstrated that psychology competencies that are specifically reflective of PsyBA professional competencies can be tracked over the course of training, both when rated by supervisors and the trainees themselves. While supervisor and trainee self-ratings revealed similar trajectories of development, trainees endorsed more improvement in aspects of practice in their final placement than did their supervisors. This may be an important point of difference and one that could be explored in placement reviews by having both supervisors and trainees to complete the PsyCET-S with emphasis on discussing any rating discrepancies. This would help to build a shared understanding of the trainee’s performance, resolve any discrepancies, and guide future learning goals. It is also important for supervisors to feel confident and comfortable to identify trainees who have “not yet reached competence” and fail students when necessary, in order to ensure public safety. As Gonsalvez et al. (Citation2021) remind us, excessively low failure rates within clinical psychology training programs are unrealistic and indicate that we still have a way to go to improving clinical supervision practices in Australia.

Assessment of trainee competence is not only essential for ensuring that graduates are safe to practice (Barnett et al., Citation2007) but is also important for enhancing student learning, which is best achieved by including self-assessment in the process (Black & Wiliam, Citation2009; Hitzeman et al., Citation2020). These principles are relevant across all streams of professional psychology, and we suggest that tools like the PsyCET-S that encourages trainee self-assessment against expert guidance, should be included in postgraduate training programs, as well as registrar programs and internships. Since the curriculum of professional psychology training programs tends to integrate the teaching and assessment of general and specialised competencies, we recommend that behavioural descriptors are drafted with specific Areas of Practice Endorsement in mind. More assertive review and evaluation of competency-based assessment practices within registrar programs to support trainee attainment of specialised professional competencies is also needed and would be a natural extension of this work. Variability of work settings, expectations, and methods of observation are also likely to influence competency ratings and should be taken into account in future research.

Perhaps one of the most important refinements needed here is to have the tool better reflect the essential need for psychologists to engage in culturally responsive practice, and the behavioural anchors should be reviewed with this in mind. The newly drafted PsyBA professional competencies (Psychology Board of Australia, Citation2023) emphasise that cultural competence, as well as reflective practice, and once accepted, should guide the next stage of this research. For instance, the behavioural vignettes could be adjusted with language from the newly drafted competencies, and additional domains with behavioural vignettes could be developed to reflect the new core competencies such as the demonstration of a health equity and human rights approach to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, families and communities. Testing a refined version of the tool that reflects the updated professional competencies might also be useful to evaluate the success of the new core competencies themselves.

Conclusion

With a move towards competency-based assessment in postgraduate psychology training programs, clinical supervisors need tools for assessing the competencies of their trainees while on placement. We developed the PsyCET-S as a means for supervisors to evaluate core professional skills and behaviours at the completion of each placement, to ensure satisfactory progress and guide future learning. This initial development and evaluation study supports the capacity of the PsyCET-S, with its sequentially ordered behavioural vignettes, to track trainee competencies over time which allows for more integrated assessment of trainees across placements and in doing so can better guide the focus of training during placements. However, the tool itself requires further refinement and validation, and doing so provides an opportunity to reflect the soon to be implemented new PsyBA professional competencies and to ensure that training pathways beyond university programs incorporate evidence-based assessment practices. Tools like the PsyCET-S can be of significant value to trainees in identifying knowledge and skills they need to demonstrate on placement in order to establish competent practice as a clinical psychologist and a way to self-monitor their progress in that journey.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (153.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [KL], upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2024.2353024

References

- Barnett, J., Erickson Cornish, J., Goodyear, R., & Lichtenberg, J. (2007). Commentaries on the ethical and effective practice of clinical supervision. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(3), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.3.268

- Barrett, J., Gonsalvez, C. J., & Shires, A. (2020). Evidence‐based practice within supervision during psychology practitioner training: A systematic review. Clinical Psychologist, 24(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12196

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability (formerly: Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education), 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

- Deane, F. P., Gonsalvez, C., Joyce, C., & Britt, E. (2018). Developmental trajectories of competency attainment amongst clinical psychology trainees across field placements. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(9), 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22619

- Dudek, N. L., Marks, M. B., & Regehr, G. (2005). Failure to fail: The perspectives of clinical supervisors. Academic Medicine, 80(10), S84–S87. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510001-00023

- Epstein, R. M., & Hundert, E. M. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.226

- Gonsalvez, C. J., Bushnell, J., Blackman, R., Deane, F., Bliokas, V., Nicholson-Perry, K., Shires, A., Nasstasia, Y., Allan, C., & Knight, R. (2013). Assessment of psychology competencies in field placements: Standardized vignettes reduce rater bias. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 7(2), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031617

- Gonsalvez, C. J., & Freestone, J. (2007). Field supervisors’ assessments of trainee performance: Are they reliable and valid? Australian Psychologist, 42(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060600827615

- Gonsalvez, C. J., Shafranske, E. P., McLeod, H. J., & Falender, C. A. (2021). Competency-based standards and guidelines for psychology practice in Australia: Opportunities and risks. Clinical Psychologist, 25(3), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284207.2020.1829943

- Gonsalvez, C. J., Terry, J., Deane, F. P., Nasstasia, Y., Knight, R., & Gooi, C. H. (2021). End-of-placement failure rates among clinical psychology trainees: Exceptional training and outstanding trainees or poor gate-keeping? Clinical Psychologist, 25(3), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284207.2021.1927692

- Hatcher, R., & Lassiter, K. D. (2007). Initial training in professional psychology: The practicum competencies outline. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.1.1.49

- Hitzeman, C., Gonsalvez, C. J., Britt, E., & Moses, K. (2020). Clinical psychology trainees’ self versus supervisor assessments of practitioner competencies. Clinical Psychologist, 24(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12183

- Holloway, E. L. (2012). Professional competence in supervision. In J. N. Fuertes, A. Spokane, & E. L. Holloway (Eds.), Specialty competencies in counselling psychology (pp. 165–181). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195386448.003.0008

- Kaslow, N. J., Grus, C. L., Campbell, L. F., Fouad, N. A., Hatcher, R. L., & Rodolfa, E. R. (2009). Competency assessment toolkit for professional psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 3(4), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015833

- Larkin, K., & Morris, T. (2015). The process of competency acquisition during doctoral training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 9(4), 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000091

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22, 276–282. 23092060; PMCID: PMC3900052. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031

- Nicholson Perry, K., Donovan, M., Knight, R., & Shires, A. (2017). Addressing professional competency problems in clinical psychology trainees. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12268

- O’Donovan, A., Halford, W. K., & Walters, B. (2011). Towards best practice supervision of clinical psychology trainees. Australian Psychologist, 46(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00033.x

- Pachana, N. A., Sofronoff, K., Scott, T., & Helmes, E. (2011). Attainment of competencies in clinical psychology training: Ways forward in the Australian context. Australian Psychologist, 46(2), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00029.x

- Popham, W. J. (1997). What’s wrong and what’s right with rubrics. Educational Leadership, 55(2), 72–75. https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/whats-wrong-right-with-rubrics/docview/224857225/se-2

- Psychology Board of Australia. (2018). Guidelines for supervisors. https://www.psychologyboard.gov.au/standards-and-guidelines/codes-guidelines-policies.aspx

- Psychology Board of Australia. (2019). Guidelines on area of practice endorsements. https://www.psychologyboard.gov.au/Standards-and-Guidelines/Codes-Guidelines-Policies.aspx

- Psychology Board of Australia. (2023). Consultation paper: Updated general registration competencies. https://www.psychologyboard.gov.au/News/Past-Consultations.aspx

- Rice, K., Schutte, N. S., Cosh, S. M., Rock, A. J., Banner, S. E., & Sheen, J. (2022). The utility and development of the competencies of professional psychology rating scales (COPPR). Frontiers in Education, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.818077

- Rodolfa, E., Bent, R., Eisman, E., Nelson, P., Rehm, L., & Pierre, R. (2005). A cube model for competency development: Implications for psychology educators and regulators. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.4.347

- Scott, T. L., Pachana, N. A., & Sofronoff, K. (2011). Survey of current curriculum practices within Australian postgraduate clinical training programmes: Students’ and programme directors’ perspectives. Australian Psychologist, 46(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00030.x

- Terry, J., Gonsalvez, C., & Deane, F. P. (2017). Brief online training with standardised vignettes reduces inflated supervisor ratings of trainee practitioner competencies. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12250

- van der Vleuten, C. P. M., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Driessen, E. W., Dijkstra, J., Tigelaar, D., Baartman, L. K. J., & van Tartwijk, J. (2012). A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Medical Teacher, 34(3), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239

- Wiliam, D., & Thompson, M. (2007). Integrating assessment with learning: What will it take to make it work? In C. A. Dwyer (Ed.), The future of assessment: Shaping teaching and learning (pp. 53–77). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315086545

- Wolf, K. (2015). Leniency and halo bias in industry-based assessments of student competencies: A critical, sector-based analysis. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(5), 1045–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1011096