Abstract

Capsule Inter-specific nest scrape reuse is rare in waders. We review this phenomenon and document it for the first time in the Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius breeding in vacant nest scrapes excavated by Northern Lapwings Vanellus vanellus.

Waders (Charadrii) usually excavate a simple nest scrape and line it sparsely with material from surroundings (del Hoyo et al. Citation1996) to be as inconspicuous as possible for predators but also to provide good thermoregulation at the same time (Reid et al. Citation2002, Mayer et al. Citation2009, Tulp et al. Citation2012). Only two species regularly use nests built by other birds (Green Sandpiper Tringa ochropus and Solitary Sandpiper Tringa solitaria) and two occasionally (Grey-tailed Tattler Tringa brevipes and Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola), especially the abandoned forest nests of thrushes (Oring Citation1973, Cramp Citation1983, Pulliainen & Saari Citation1991, del Hoyo et al. Citation1996).

Creating a new nest scrape for breeding is probably not energy demanding (Amat et al. Citation1999) and old nest scrapes are often left unused even if they are available in the breeding territory (Gratto et al. Citation1985). In addition, the process of excavation has been described as an important part of the courtship ritual prior to copulation (Cramp Citation1983). Nevertheless, there are many examples of reuse of the nest scrape by the same or different individuals in several wader species within the same or in the subsequent breeding season. The Birds of North America database (Poole Citation2013) refers to intra-specific nest scrape reuse in 26 out of 50 American wader species, and it has been widely documented elsewhere (Parr Citation1980, Cramp Citation1983, Amat et al. Citation1999, Soloviev et al. Citation2001, Bertolero Citation2002, Schekkerman et al. Citation2004), but it occurs only at low frequency (Poole Citation2013). In contrast, use of the nest scrape by different wader species (inter-specific reuse) has been recorded only exceptionally ( containing all the records we could find). Here we document its occurrence in two European species, the Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius and Northern Lapwing Vanellus vanellus.

Table 1. Inter-specific nest scrape reuse in waders.

The Little Ringed Plover is a common wader species distributed widely across Europe (BirdLife International Citation2004, Delany et al. Citation2009). It primarily breeds in habitats dominated with bare ground and low sparse vegetation close to water, including human-altered environment such as the bottoms of dry ponds, sandpits and other post-industrial sites (Cramp Citation1983, Parrinder Citation1989, del Hoyo et al. Citation1996, Fojt et al. Citation2000). In the Czech Republic in addition to these habitats (Hudec & Št'astný Citation2005, Št'astný et al. Citation2006), arable land, especially freshly sowed maize fields and parts of wet fields with sand or gravel, seem to be another important breeding habitat for the species, at least in South Bohemia in recent years (Cepáková et al. Citation2007, Kubelka unpubl. data). In the Little Ringed Plover, the male usually excavates several nest scrapes that are subsequently lined with small stones and pieces of vegetation, and the female chooses one of these during courtship (Walters Citation1956, Cramp Citation1983, Hudec & Št'astný Citation2005).

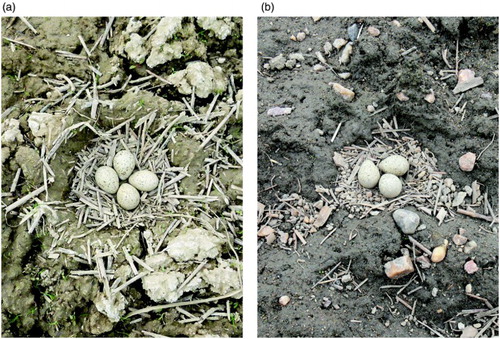

During a study of a Northern Lapwing (hereafter lapwing) population in South Bohemia, Czech Republic, we found two clutches of Little Ringed Plovers (hereafter plover) on 21 April 2013, placed in nest scrapes excavated by lapwings. The plover nests were placed 125 m apart from each other within a lapwing breeding colony (24 m and 11 m from the nearest active lapwing nests, respectively) consisting of ten lapwing nests in the middle of one large field (35 ha) near Žabovrˇesky (GPS: 48°59′53″N, 14°20′47″E), which was a wet ploughed field at the time of courtship and at the early incubation stage of both species. The inner cup diameter of plover nests (5.5–6.5 cm, n = 13) is smaller than that of lapwings (7–16 cm, n = 96) in the Czech Republic (Hudec & Št'astný Citation2005). At the study site, the lapwing nest scrapes with plover eggs appeared similar to other unused lapwing nest scrapes in the surroundings. One nest scrape (inner cup diameter: 12 cm, cup depth: 3.5 cm) with plover eggs was sparsely lined with pieces of straw but without stones (a), which does not correspond to the usual plover nest scrape lining (Cramp Citation1983), repeatedly found in the arable fields of South Bohemia (own unpubl. data, b). All eight eggs from the two plover clutches (four and four eggs) hatched successfully.

Figure 1. (a) Clutch of a Little Ringed Plover C. dubius in a nest scrape excavated by a Northern Lapwing V. vanellus, 27 May 2013, photo by MŠ. (b) An example of a ‘normal’ Little Ringed Plover nest in a ploughed field 20 km from nest (a), 9 April 2010, photo by VK.

The majority of previously known inter-specific nest scrape reuses occurred after breeding of the host wader species. However, in this case, the plovers probably used unused lapwing nest scrapes. Although we cannot completely exclude possible predation of the lapwing nests during the egg-laying period and their subsequent reuse by plovers, this is unlikely due to our regular visits of the locality. We did not observe any physical conflict between the two species at the breeding ground and lapwings seemed to tolerate plovers in their territories. We suppose (according to the timing of breeding) that the plovers chose one of the nest scrapes which were excavated by lapwings during their courtship but were later unused for egg-laying and thus were free for the plovers.

The advantage of nest scrape reuse could be to save energy, similar to the arguments to support nest reuse (Pearson Citation1974). Saved energy can be invested in more intense display and courtship to potential mates as in the Fan-tailed Warbler Cisticola juncidis (Ueda Citation1989) or can lead to earlier laying of replacement clutches as in the Eastern Kingbird Tyrannus tyrannus in North America (Cancellieri & Murphy Citation2013). The energy-saving hypothesis is supported by the fact that nest scrapes of Kentish Plovers Charadrius alexandrinus were reused more often by the same species in the situations when excavating due to firm soil was apparently more demanding (Amat et al. Citation1999).

In the plover and in other waders, where the female chooses one of the nest scrapes present in the territory (Cramp Citation1983), the incorporation of an already made nest scrape in the territory could increase the attractiveness of a displaying male. Moreover, a bigger nest scrape could serve as a supernormal stimulus (Staddon Citation1975) and the female could consider the male displaying beside this bigger nest scrape as more attractive. A bigger nest scrape could therefore be preferred for breeding to smaller ones excavated by the plovers.

The nearby presence of breeding lapwings could be an important advantage of the lapwing nest scrape usage. Lapwings are known for their aggressiveness in expelling avian predators from the surroundings of their nests (Elliot Citation1985, Kis et al. Citation2000). Deterrence of predators is more efficient in bigger colonies (Berg Citation1996, Šálek & Šmilauer Citation2002) such as the aggregation at the study site. As in Nankinov (Citation1978), plovers at the study site could principally have sought out this ‘lapwing protective umbrella’. Frequent observations of courting plovers at other lapwing breeding sites nearby to the study area (own unpubl. data) suggest that the phenomenon could be more widespread. The hatching success of plovers in South Bohemia is higher in fields compared to bottoms of dried fishponds which are traditional breeding habitat there (Cepáková et al. Citation2007). The presence of lapwing breeding colonies could play a significant role in this because lapwing colonies are currently situated particularly on arable land (Kubelka et al. Citation2012).

Alternatively, the finding of a plover nest in a tractor wheel track in East Bohemia (V. Štorek, pers. comm.) suggests that plovers are able to make use of similar unusual situations. It is therefore possible that plovers use any suitable depressions for their nests. Moreover, the pre-laying period of lapwings in 2013 was prolonged due to frosts at the end of March. Lapwing males thus had more time to excavate nest scrapes and indeed, more nest scrapes were found in the surroundings of active lapwing nests than in other years (Kubelka & Šálek Citation2013). Therefore, this surplus of vacant lapwing nest scrapes in 2013 could also have significantly influenced plover nest site selection.

At least 24 cases of inter-specific nest scrape reuse have been documented so far in 22 wader species (17 wader species used a vacant nest scrape built by another species) and in the majority of these cases it has only been recorded once. Most of them come from the Arctic (), probably as a result of longer persistence of nest scrapes in the stable arctic environment (Gratto et al. Citation1985, Soloviev et al. Citation2001) and possibly the energy demands for excavating/creating a nest scrape in cold Arctic conditions render nest scrape reuse more convenient. It could, however, also be caused simply by the fact that wader communities are thoroughly investigated in the Arctic, where several species breed close to each other in the same habitat (Soloviev et al. Citation2001) rendering the community more prone to inter-specific nest scrape reuse and its observation more likely. Generally, the species that reuse nests of other species do not differ much in size from the host species (). In contrast, in the case of plovers and lapwings, this difference in size is unusually large.

We conclude that plovers used the option of breeding in vacant lapwing nest scrapes in a ploughed field for one or a combination of the following reasons: (1) vacant lapwing nest scrapes were used simply as available suitable depressions in plover territories unconnected to their excavation by lapwings and the surplus of vacant lapwing nest scrapes in 2013 could have played an important role in what we observed; (2) bigger lapwing nest scrapes acted as a supernormal stimulus, which attracted courting plovers; (3) plover males enhanced their attractiveness to potential mates by including additional vacant nest scrapes in their territory and (4) plovers were attracted to breed in the proximity of lapwings to benefit from their anti-predation behaviour. All of these suggestions represent clear hypotheses that can be tested by experiment with a larger sample size.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to R. Piálková, A. Vondrka, J. Vlček, Z. Karlíková and M. Nacházelová for their kind help in the field and to local farmers for their assistance. We are also indebted to J. Hansen, M. Y. Soloviev, P. Tomkovich and C. Kuepper for providing us with information about inter-specific nest scrape reuse. The first of them also contributed by useful comments on the earlier draft of the manuscript. We thank E. Cepáková for improvement of our English and W. Cresswell and two anonymous reviewers for their comments which significantly improved the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Life Sciences Prague [grant CIGA number 20124218].

References

- Amat, J.A., Fraga, R.M. & Arroyo, G.M. 1999. Reuse of nesting scrapes by Kentish Plovers. Condor 101: 157–159. doi: 10.2307/1370457

- Berg, Å. 1996. Predation on artificial, solitary and aggregated wader nests on farmland. Oecologia 107: 343–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00328450

- Bertolero, A. 2002. Interannual nest reuse by Redshank Tringa totanus. Revista Catalana d'Ornitologia 19: 44–46.

- BirdLife International. 2004. Birds in Europe: Population Estimates, Trends and Conservation Status. BirdLife International (BirdLife Conservation Series No. 12), Cambridge.

- Cancellieri, S. & Murphy, M.T. 2013. Experimental examination of nest reuse by an open-cup-nesting passerine: time/energy savings or nest site shortage? Anim. Behav. 85: 1287–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.03.017

- Cepáková, E., Šálek, M., Cepák, J. & Albrecht, T. 2007. Breeding of Little Ringed Plovers Charadrius dubius in farmland: do nests in fields suffer from predation? Bird Study 54: 284–288. doi: 10.1080/00063650709461487

- Cramp, S. (ed.) 1983. Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa: The Birds of the Western Palearctic Volume III: Waders to Gulls. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Delany, S., Scott, D., Dodman, T. & Stroud, D. (eds) 2009. An Atlas of Wader Populations in Africa and Western Eurasia. Wetlands International, Wageningen.

- Elliot, R.D. 1985. The exclusion of avian predators from aggregations of nesting lapwings (Vanellus vanellus). Anim. Behav. 33: 308–314. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(85)80144-5

- Fojt, E., Triplet, P., Robert, J-C. & Stillman, R.A. 2000. Comparison of the breeding habitats of Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius and Kentish Plover Charadrius alexandrinus on a shingle bed. Bird Study 47: 8–12. doi: 10.1080/00063650009461155

- Gratto, C.L., Morrison, R.I.G. & Cooke, F. 1985. Philopatry, site tenacity, and mate fidelity in the Semipalmated Sandpiper. Auk 102: 16–24. doi: 10.2307/4086818

- del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. (eds) 1996. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 3. Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

- Hudec, K. & Št'astný, K. (eds) 2005. Fauna ČR. Ptáci – Aves 2/I. Academia, Praha.

- Johnson, O.W. & Connors, P.G. 2010. American Golden-Plover (Pluvialis dominica). In Poole, A. (ed.) The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca. Available from http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/201

- Johnson, O.W., Bruner, P.L., Bruner, A.E. & Johnson, P.M. 2007. American Golden-Plovers on the Seward Peninsula, Alaska: a new longevity record for the species and other breeding ground observations. Wader Study Group Bull. 114: 56–59.

- Kis, J., Liker, A. & Szekely, T. 2000. Nest defence by Lapwings: observations on natural behaviour and an experiment. Ardea 88: 155–163.

- Kubelka, V. & Šálek, M. 2013. [Effect of extreme weather conditions on the course of breeding of the Northern Lapwing (Vanellus vanellus) in 2013.] Sylvia 49: 145–156 (in Czech with a Summary in English).

- Kubelka, V., Zámečník, V. & Šálek, M. 2012. [Survey of breeding Northern Lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) in the Czech Republic in 2008: results and effectiveness of volunteer work.] Sylvia 48: 1–23 (in Czech with a Summary in English).

- Lowther, P.E., Douglas III, H.D. & Gratto-Trevor, C.L. 2001. Willet (Tringa semipalmata). In Poole, A. (ed.) The Birds of North America Online, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca. Available from http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/579

- Mayer, P.M., Smith, L.M., Ford, R.G., Watterson, D.C., McCutchen, M.D. & Ryan, M.R. 2009. Nest construction by a ground-nesting bird represents a potential trade-off between egg crypticity and thermoregulation. Oecologia 159: 893–901. doi: 10.1007/s00442-008-1266-9

- Moitoret, C.S., Walker, T.R. & Martin, P.D. 1996. Predevelopment Surveys of Nesting Birds at Two Sites in the Kuparuk Oilfield, Alaska, 1988–1992. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Technical Report NAES-TR-96–02, Fairbanks.

- Nankinov, D.N. 1978. [Migration and breeding of some species of the order Charadriiformes on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland.] Acta Ornithol. 16: 315–323 (in Russian).

- Oring, L.W. 1973. Solitary Sandpiper early reproductive behavior. Auk 90: 652–663. doi: 10.2307/4084164

- Parr, R. 1980. Population study of Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria, using marked birds. Ornis Scand. 11: 179–189. doi: 10.2307/3676122

- Parrinder, E.D. 1989. Little Ringed Plovers Charadrius dubius in Britain in 1984. Bird Study 36: 147–153. doi: 10.1080/00063658909477019

- Pearson, D.L. 1974. Use of abandoned cacique nests by nesting Troupials (Icterus icterus): precursor to Parasitism? Wilson Bull. 86: 290–291.

- Poole, A. (ed.) 2013. The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca. Available from http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/

- Pulliainen, E. & Saari, L. 1991. Breeding biology of the Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola in eastern Finnish Lapland. Ornis Fennica 68: 127–128.

- Reid, J.M., Cresswell, W., Holt, S., Mellanby, R.J., Whitfield, D.P. & Ruxton, G.D. 2002. Nest scrape design and clutch heat loss in Pectoral Sandpipers (Calidris melanotos). Funct. Ecol. 16: 305–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00632.x

- Robinson, J.A., Reed, J.M., Skorupa, J.P. & Oring, L.W. 1999. Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus). In Poole, A. (ed.) The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca. Available from http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/449

- Šálek, M. & Šmilauer, P. 2002. Predation on Northern Lapwing Vanellus vanellus nests: the effect of population density and spatial distribution of nests. Ardea 90: 51–60.

- Schekkerman, H., Tulp, I., Calf, K.M. & de Leeuw, J.J. 2004. Studies on Breeding Shorebirds at Medusa Bay, Taimyr, in Summer 2002. Alterra-rapport 922, Wageningen.

- Soloviev, M.Y., Golovnyuk, V.V., Sviridova, T.V. & Rakhimberdiev, E.N. 2001. Breeding Conditions and Numbers of Birds on Southeastern Taimyr, 2000. Report of the Wader Monitoring Project at Taimyr, Moscow.

- Staddon, J.E.R. 1975. A note on the evolutionary significance of “supernormal” stimuli. Am. Nat. 109: 541–545. doi: 10.1086/283025

- Št'astný, K., Bejček, V. & Hudec, K. 2006. Atlas hnízdního rozšíření ptáku˚ v České republice 2001–2003. Aventinum, Praha.

- Tulp, I., Schekkerman, H. & de Leeuw, J. 2012. Eggs in the freezer: energetic consequences of nest site and nest design in Arctic breeding shorebirds. PLoS One 7: e38041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038041

- Ueda, K. 1989. Re-use of courtship nests for quick remating in the polygynous Fan-tailed Warbler Cisticola juncidis. Ibis 131: 257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.1989.tb02768.x

- Walker, B.M., Senner, N.R., Elphick, C.S. & Klima, J. 2011. Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica). In Poole, A. (ed.) The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca. Available from http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/629

- Walters, J. 1956. Eirüeckgewinnung und Nistplatzorientierung bei See- und Flussregenpfeifer (Charadrius alexandrinus und dubius). Limosa 29: 103–129.