Abstract

Capsule Multiple tracking methods (colour-rings, plumage-markings and GPS-loggers) revealed that adult Sandwich Terns Thalasseus sandvicensis from the Netherlands showed prospecting behaviour in other colonies within Northwest Europe. Birds were recorded from a few kilometres to over 850 km away and in different countries around the Southern North Sea. Our data suggest large-scale connectivity between Northwest European Sandwich Tern colonies. Such connectivity is potentially of great importance when modelling the population structure of this species.

Terns, like many other seabirds, visit future breeding sites before actual settlement, a period generally defined as prospecting, which can either take place before first reproduction or in later stages of life (Reed et al. Citation1999, Schjørring et al. Citation1999, Dittmann et al. Citation2005, Citation2007, Major Citation2011, Ponchon et al. Citation2012). Visiting other breeding sites can allow prospecting individuals to gather information on the quality of the local breeding site or surrounding foraging areas in order to select an optimal breeding site for the following year. This behaviour has been described in many seabird species, but most studies on prospecting behaviour have largely focused on sub-adult and non-breeding (sabbatical) adult birds (Cadiou et al. Citation1994, Dittmann et al. Citation2007, Votier et al. Citation2011). Nevertheless, failed breeders and even successful breeders are also known to visit other colonies, either before a breeding season or just after, as prospecting for the next season (Cadiou et al. Citation1994, Calabuig et al. Citation2010, Ponchon et al. Citation2012). Adult birds probably prospect in other colonies to maximize their breeding success in the following year (Boulinier & Danchin Citation1997), but the extent and nature of prospecting behaviour varies between species and associated migration strategies. For example long-distance migratory birds, like Sandwich Terns, have potentially less time for prospecting behaviour than sedentary birds (Reed et al. Citation1999).

Sandwich Terns can show site tenacity to their natal colony (P. Wolf, E. Stienen unpubl. data), although are also highly nomadic and colony-site shifts occur regularly (Stienen Citation2006). These shifts are often caused by breeding failure or disturbance by predators (Ratcliffe et al. Citation2000, Noble-Rollin & Redfern Citation2002, Stienen Citation2006), but for some shifts an obvious reason is lacking. Prospecting in this species has previously been suggested for immature, non-breeders and failed breeders (references within the review of Reed et al. Citation1999), and the exploration of other breeding sites by adult birds has also been suggested (Stienen Citation2006, Fijn et al. Citation2011). This has previously been based on incidental ring recoveries and direct evidence of actual prospecting flights has never been confirmed.

Several reasons to investigate prospecting behaviour have been identified by Ponchon et al. (Citation2012) who explicitly stated that the ongoing miniaturization of modern tracking devices results in increasing possibilities to adequately study prospecting flights. Here, we report an example of such, describing prospecting in Sandwich Terns in the same year as a breeding attempt and based on data collected with several different tracking methods.

Between 2009 and 2013, a total of 82 nesting adult Sandwich Terns were caught using walk-in cages and spring traps in a colony in the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt estuary on the Scheelhoek Eilanden (NLD, N 51.8126°, E 4.0726°). All birds were ringed with a uniquely numbered metal ring. In 2009, a plain yellow plastic ring was added to the other leg to allow quick recognition in the field. In 2010, 2012 and 2013 field-readable plastic colour-rings with a three-digit code (blue with white digits in 2010 and 2012, and white with black digits in 2013) were added to allow the identification of individuals. Combinations of various body parts (head, both wings and tail) of most birds were colour-dyed with picric acid (yellow/orange) or silver nitrate (dark brown) to increase detection chances and recognition in the field.

In all years, a number of birds (in total n = 50) were equipped with tracking devices. All these individuals were captured during the incubation or chick-rearing stages. Handling time (capture to release) was approximately 15 minutes. In 2009 and 2010, 30 birds were equipped with VHF-transmitters (Microtes, 1 g, L:12 × W:8 × H:6 mm) that were glued to trimmed feathers on the back (cf. Warnock & Warnock Citation1993) in order to study habitat use and colony attendance. In 2012 and 2013, 20 individuals were equipped with GPS-loggers (Ecotone ALLE-55 GPS-UHF, ∼4 g, L:50 × W:15 × H:8 mm). Seven of these were attached to feathers on the back with TESA tape (No. 4651; Beiersdorf AG, Hamburg, Germany, cf. Wilson et al. Citation1997). On the remaining 13, a specially designed backpack harness (cf. Kenward Citation1985) made out of thick elasticated fishing wire (Preston Innovations Slip Elastic, diameter 2.2 mm) was used. The GPS-loggers archived GPS positions at 5 (standard battery) or 15 (solar-powered) minute intervals to the device memory and also included date, time, latitude, longitude and speed. Data were automatically downloaded to base stations placed in the colony from a distance up to approximately 90 m. Positional data were analysed using Quantum GIS.

In summary, our total sample size was 82 individually colour-marked birds. In 2009, a total of 15 birds were plumage-marked only. In 2010, a total of six birds received colour-rings only, and another ten were colour-ringed and plumage-marked. In 2013, 24 birds were colour-ringed, of which 10 were also fitted with a GPS-logger, and 5 of these were also plumage-marked. Of the 27 birds marked in 2014, 7 were colour-ringed only, 10 colour-ringed and plumage-marked, 5 colour-ringed and fitted with a GPS-logger and another 5 received a colour-ring, plumage-marking and a GPS-logger.

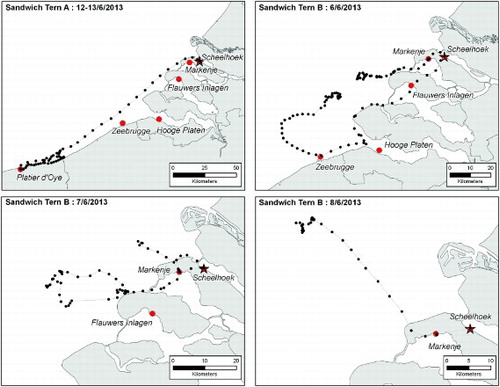

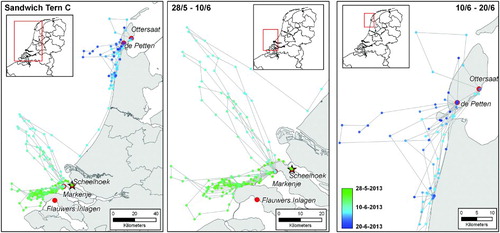

GPS-loggers yielded distributional data for eight chick-rearing (seven in 2012 and one in 2013) and four failed breeders (2013). The exact date of brood failure was unknown but was likely to be fairly soon after tagging. Tag loss due to malfunctioning of attachment technique (n = 3) and immediate colony desertion (n = 5) explained the lack of data for the other eight birds. Typically, data were collected over a period of 2–6 days, however one logger (an experimental logger with solar panel) recorded data for 22 days. Three out of the four failed breeders showed prospecting behaviour in other colonies within the same year ( & 2). In contrast, none of the birds that were rearing chicks showed prospecting behaviour, at least not during the time that the loggers were active.

Of the three birds showing prospecting behaviour, one flew to France on 11 June 2013, one day after being marked. After spending the night on a beach near Dunkerque, it visited the colony at the Réserve Naturelle du Platier d'Oye (FRA, N 51.005°, E 2.076°) for ∼40 minutes before making a foraging trip at sea (, bird A). After a second night at the same beach it flew, helped by a tailwind of force 6 Beaufort wind scale, in a straight line back to the original breeding site at the Scheelhoek Eilanden; a distance of 130 km in 84 minutes (average ground speed of 91 km/h). The second prospecting bird visited the colony sites of Markenje (NLD, N 51.801°, E 3.960°) for ∼45 minutes and Zeebrugge (BEL, N 51.359°, E 3.213°) for less than 5 minutes, as well as the surroundings of the colony at Hooge Platen (NLD, N 51.394°, E 3.625°) before flying to the open sea to forage (, bird B). During the following two days it visited the colony at Markenje (for between 30 and 75 minutes) on both the outward and inward journeys of a foraging trip before travelling back to the Scheelhoek Eilanden. A third Sandwich Tern was tracked between 28 May and 20 June 2013 (, bird C). Two days after its breeding attempt failed it moved to the nearby colony of Markenje and performed daily offshore foraging flights from this colony for the next ten days. On the eleventh day it flew north towards the Wadden Sea, where it made daily foraging flights from the colonies at Ottersaat (NLD, N 53.052°, E 4.860°) and De Petten (NLD, N 51.394°, E 4.756°) on the island of Texel ().

Figure 1. Prospecting visits to other colonies (red circles) and foraging flights of two Sandwich Terns from the colony at the Scheelhoek Eilanden (red star), the Netherlands. Recorded GPS locations (black dots) are connected with a straight line for visualization purposes.

Figure 2. Recorded GPS locations (coloured dots) of a Sandwich Tern after breeding failure. Dots are coloured from green to blue with ascending date and a straight line is depicted between subsequent points for visualization purposes. This bird prospected in a nearby colony (red circles), left the surroundings of the colony where it started breeding (red star) 11 days after tagging, and prospected in two colonies on the island of Texel, the Netherlands. The left panel shows the entire period between 28 May (tagging) and 20 June 2013 (last data download), the middle and right panels the detailed views of the southern and northern geographical regions, respectively.

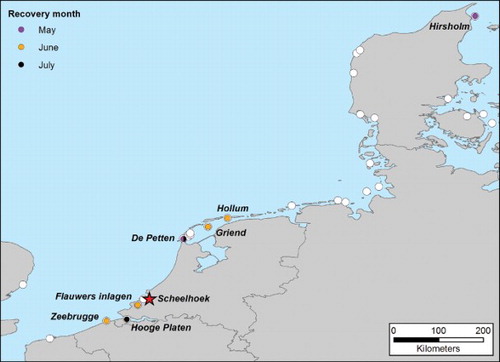

Evidence of prospecting visits by adult terns could also be extracted from the colour-ring observations of three birds in 2009, two birds in 2010, and four birds in 2013 () in seven different colonies in the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark. In 2009, one adult moved to a colony in De Petten, where it spend between 24 and 27 May, and was subsequently recorded in a colony near Hollum (NLD, N 53.427°, E 5.643°) on 12 June. That year, another individual that probably raised a chick successfully, was present in the colony at the Hooge Platen between 3 and 7 July, while another individual was recorded on 24 May 2009 in the colony at Hirsholm (DEN, N 57.480°, E 10.630°), 870 km to the northeast. Two adults colour-ringed in 2010 were seen between 7 and 12 June 2010 in the colony at the Flauwers Inlagen (NLD, N 51.681°, E 3.841°) amongst incubating adults, but no further breeding behaviour other than performing courtship was recorded. In 2013, one bird visited the colony in Zeebrugge on 21 June, another bird was recorded in the colony in de Petten on 2 July, and two individuals were seen on 13 and 14 June in the colony at Griend (NLD, N 53.250°, E 5.250°), all suggesting prospecting visits.

Figure 3. Colour-ring recoveries (coloured dots according to recovery month) of prospecting adult Sandwich Terns from the Scheelhoek Eilanden colony (red star) in other colonies (white circles) in Denmark (2009–2012: Gregersen & Bregnballe (Citation2014), 2013: J. Gregersen & T. Bregnballe, pers. comm.), Germany (2009–2013: B. Hälterlein & T. Grünkorn, pers. comm., Garthe & Flore Citation2007), the Netherlands, Belgium and France (2009–2013: K. de Kraker, pers. comm.) and the UK (Mitchell et al. Citation2004).

Adult breeding dispersal is common in Sandwich Terns (Møller Citation1981, Noble-Rollin & Redfern Citation2002, Stienen Citation2006, Popov et al. Citation2012), and has been confirmed for the Scheelhoek Eilanden colony with recorded breeding adults ringed in Spain, Scotland, Belgium, the Wadden Sea and other Delta-colonies (P. Wolf, E. Stienen unpubl. data). Stienen (Citation2006) and Fijn et al. (Citation2011) already suggested that the high exchange rate between the various Sandwich Tern colonies in Northwest Europe is probably facilitated by frequent visits to other breeding sites before or after the breeding period. Despite the limited sample size, this study confirms this by using direct evidence from GPS tracking data. Some birds visited nearby colonies but still returned to the home colony, while another bird visited several colonies much further away from the home colony. Here, they might have collected information about the local food availability as well as the breeding success of conspecifics in other colonies. Gathering information about potential future breeding sites would be highly advantageous for a mobile species showing high rates of interchange between colonies. However, further studies are needed to explain the value of such information for future breeding and how this affects dispersal behaviour of the terns.

In our study the majority of prospecting birds were failed breeders. One possibility is that birds experienced the tagging procedure as a ‘predation attempt’ indicating an unsuitable colony, which might have induced subsequent colony desertion and increased prospecting behaviour as they searched for better conditions elsewhere. However, the limited battery capacity of the GPS-loggers prevented the recording of prospecting flights of successful birds later on in the season. It is likely that this group also undertakes prospecting. This theory is supported by a re-sighting of a colour-ringed bird that is assumed to have bred successfully. Moreover, we colour-ringed large numbers of juveniles (488 in 2012 and 398 in 2013) in our study, many of which were subsequently frequently recorded in other colonies. In 2012, eight juveniles (1.6%) were recorded at two other colony sites in the Netherlands (Ottersaat and de Petten), whilst in 2013 a total of nine juveniles (2.3%) were recorded in five other colonies (Flauwers Inlaag, Wagejot (N 53.088°, E 4.898°), Ottersaat and de Petten (all NLD), and Coquet Island (UK, N 55.336°, W 1.538°)). Juvenile Sandwich Terns are still fed for a long time after fledging (Stienen Citation2006), and therefore the presence of young colour-ringed birds in other colonies might be indicative of post-breeding prospecting by their parents. This corresponds with recorded influxes into Danish and German colonies of juveniles originating from Griend and the presence of young birds from unknown foreign colonies in the breeding colony in Zeebrugge (E. Stienen unpubl. data). However, successful breeders are more restricted in time than failed breeders and might have less opportunity to prospect during the intensive post-fledging period. Successful breeders may also prospect just before the subsequent breeding season even if they seem to start breeding primarily at the successful locations of the previous year. If local conditions have severely deteriorated, they might consider changing colony, relying on the information collected by prospecting.

Our study supports the theory that birds from the different Sandwich Tern colonies in Western Europe all belong to a meta-population that is able to quickly respond to changing breeding conditions by moving between colony sites (Møller Citation1981, Ratcliffe et al. Citation2000, Stienen Citation2006). After the breeding season, Sandwich Terns disperse throughout the coastal areas around their breeding colony and to neighbouring countries before migrating south to the African wintering areas. Sandwich Terns breeding in the UK often cross the North Sea to visit Dutch, German and Danish coastal waters (Noble-Rollin & Redfern Citation2002) and many Dutch and Belgian Sandwich Terns first migrate to the UK or to Denmark (Brenninkmeijer & Stienen Citation1997, Fijn et al. Citation2011), although in this study no prospecting visits to the UK could be confirmed, except for one juvenile bird recorded at Coquet Island that might have accompanied its prospecting parent(s).

The strong connectivity between colonies and the high exchange rate between colonies has major implications for population modelling and conservation efforts targeted at this species. For such species the quality of a breeding site should not only be expressed in terms of breeding numbers of one colony, but most likely other quality indicators such as food availability and predator pressure, should be included as well. Moreover, a proper assessment at meta-population level for the region from northern France, the eastern UK, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany to western and northeast Denmark, is required to adequately assess population dynamics and trends for this nomadic species.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was part of the monitoring programme into the effects of the compensation measures designed for the construction of the seaward expansion of the Rotterdam Harbour (‘Tweede Maasvlakte’). This programme (PMR-NCV) was initiated by the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment and commissioned by Deltares (G. van der Kolff, T. Prins, A. Boon and J. Reijnders) and Rijkswaterstaat WVL (M. van Eerden and K. Borst). Bureau Waardenburg, INBO Research Institute for Nature and Forest, and Delta Project Management carried out the research on terns within this project in a consortium with a lead of IMARES Wageningen-UR (I. Tulp and H. Heessen). The authors would like to thank M. van der Walle, A. Braarup Cuykens and N. Vanermen for help in the field. Fieldwork was carried out in two nature reserves of Natuurmonumenten and W. van Steenis, H. Meerman, J. de Roon and E. Menkveld are thanked for their cooperation and hospitality. All volunteers reading colour-rings are greatly thanked for their effort. T. Bregnballe, A. Møller, K. de Kraker, S. Garthe, B. Hälterlein, T. Grünkorn and M. Stock are thanked for information about colonies in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. P. van Horssen and H. Soomers are thanked for help with providing GIS maps. We thank J. van der Winden, M. Collier, W. Cresswell, and two anonymous reviewers for their input to improve the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Boulinier, T. & Danchin, E. 1997. The use of conspecific reproductive success for breeding patch selection in terrestrial migratory species. Evol. Ecol. 11: 505–517. doi:10.1007/s10682-997-1507-0

- Brenninkmeijer, A. & Stienen, E.W.M. 1997. Migratie van de Grote Stern Sterna sandvicensis in Denemarken en Nederland. IBN Rapport 97/302. Instituut voor Bos- en Natuuronderzoek (IBN-DLO), Wageningen. (In Dutch.)

- Cadiou, B., Monnat, J.Y. & Danchin, E. 1994. Prospecting in kittiwake, Rissa tridactyla: different behavioural patterns and the role of squatting in recruitment. Anim. Behav. 47: 847–856. doi:10.1006/anbe.1994.1116

- Calabuig, B., Ortego, J., Aparicio, J.M. & Cordero, P.J. 2010. Intercolony movements and prospecting behaviour in the colonial lesser kestrel. Anim. Behav. 79: 811–817. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.12.007

- Dittmann, T., Zinsmeister, D. & Becker, P.H. 2005. Dispersal decisions: common terns, Sterna hirundo, choose between colonies during prospecting. Anim. Behav. 70: 13–20. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.09.015

- Dittmann, T., Ezard, T.H.G. & Becker, P.H. 2007. Prospectors’ colony attendance is sex-specific and increases future recruitment chances in a seabird. Behav. Process. 76: 198–205. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2007.05.002

- Fijn, R.C., Wolf, P., Courtens, W., Poot, M.J.M. & Stienen, E.W.M. 2011. Post-breeding dispersal, migration and wintering of Sandwich Terns Thalasseus sandvicensis from the southwestern part of the Netherlands. Sula 24: 121–135. (In Dutch, English summary and figure captions.)

- Garthe, S. & Flore, B.-O. 2007. Population trend over 100 years and conservation needs of breeding sandwich terns (Sterna sandvicensis) on the German North Sea coast. J. Ornithol. 148: 215–227. doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0123-7

- Gregersen, J. & Bregnballe, T. 2014. Splitterne Sterna sandvicensis. Dansk Ornitologisk Forenings Tidsskrift. (In press.)

- Kenward, R.E. 1985. Raptor radio-tracking and telemetry. In Newton, I. & Chancellor, R.D. (eds.) Conservation Studies on Raptors, Vol. 5: 409–420. International Council for Bird Preservation Technical Publication. International Council for Bird Preservation, Cambridge, UK.

- Major, H.L. 2011. Prospecting decisions and habitat selection by a nocturnal burrow-nesting seabird. PhD Thesis, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, 143 pp.

- Mitchell, P.I., Newton, S.F., Ratcliffe, N. & Dunn, T.E. 2004. Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland: Results of the Seabird 2000 Census (1998–2002). T. and A.D. Poyser, London.

- Møller, A.P. 1981. The migration of European Sandwich Terns Sterna s. sandvicensis. Vogelwarte 31: 74–94 & 149–168.

- Noble-Rollin, D. & Redfern, F. 2002. Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis. In Wernham, C.V., Toms, M.P., Marchant, J.A., Clark, G.M., Siriwardena, G.M., & Baillie, S.R. (eds.) The Migration Atlas: Movements of the Birds of Britain and Ireland, 381–384. Poyser, London.

- Ponchon, A., Grémillet, D., Doligez, B., Chambert, T., Tveraa, T., González-Solís, J. & Boulinier, T. 2012. Tracking prospecting movements involved in breeding habitat selection: insights, pitfalls and perspectives. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4: 143–150. doi:10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00259.x

- Popov, D., Kirov, D. & Zhelev, P. 2012. Results from Marking of Sandwich Terns (Sterna sandvicensis) with Colour Rings and Radio Transmitters at Pomorie Lake. Acta Zool. Bulg. Suppl. 4: 143–150.

- Ratcliffe, N., Pickerell, G. & Brindley, E. 2000. Population trends of little and Sandwich Terns Sterna albifrons and S. sandvicensis in Britain and Ireland from 1969 to 1998. Atlantic Seabirds 2: 211–226.

- Reed, J.M., Boulinier, T., Danchin, E. & Oring, L.W. 1999. Informed dispersal: prospecting by birds for breeding sites. Curr. Ornith. 15: 189–259. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4901-4_5

- Schjørring, S., Gregersen, J. & Bregnballe, T. 1999. Prospecting enhances breeding success of first-time breeders in the great cormorant. Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis. Anim. Behav. 57: 647–654. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0993

- Stienen, E.W.M. 2006. Living with gulls: trading off food and predation in the Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis. Alterra Scientific Contributions, 15. PhD Thesis, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen: Groningen, 192 pp.

- Votier, S.C., Grecian, W.J., Patrick, S. & Newton, J. 2011. Inter-colony movements, at-sea behaviour and foraging in an immature seabird: results from GPS-PPT tracking, radio-tracking and stable isotope analysis. Mar. Biol. 158: 355–362. doi:10.1007/s00227-010-1563-9

- Warnock, N. & Warnock, S. 1993. Attachment of radio transmitters to sandpipers: review and methods. Wader Study Group Bull. 70: 28–30.

- Wilson, R.P., Pütz, K., Peters, G., Culik, B., Scolaro, J.A., Charrassin, J.-B. & Ropert-Coudert, Y. 1997. Long-term attachment of transmitting and recording devices to penguins and other seabirds. Wildlife Soc. Bull. 25: 101–106.