ABSTRACT

This article explores the state of higher education studies today, suggesting that in many ways it can be considered a vibrant field. In the UK, this is evidenced by the relatively large number of REF2021 submissions that had a higher education focus, and the emphasis higher education institutions are increasingly placing on conducting their own pedagogical research (in some respects, driven by market imperatives). In addition, the field has become more strongly international in its orientation, with more collaborative work, and a greater number of scholars engaging with issues beyond their own nation-state. However, the article also argues that there are various ‘threats’ bound up with this greater internationalisation – not least, the limited definition of the ‘international’ that is often implicit in our scholarship.

Introduction

Scholarship on higher education research (i.e., research on the topic of higher education) within the UK has frequently emphasised some of the weaknesses with work in this area, sometimes juxtaposing it with more established areas, such as school-orientated research. Critiques have typically focussed on four main areas. First, some scholars have contended that theory is often largely absent from higher education research. Ashwin (Citation2012) and Tight (Citation2014), for example, have both argued that the conceptual framing of studies and theoretical development through research are relatively weak. For Ashwin, this is because of the frequent lack of explicit conceptualisation of the object of research in the writing-up of research, and the common absence of a discursive gap between how research objects are conceptualised and how data are subsequently analysed. Papatsiba and Cohen (Citation2020) point instead to the impact of the wider environment, suggesting that a lack of ‘power, authority, autonomy and institutional space’ for higher education research within UK universities has limited researchers’ ability to spend time on theoretical development.

Second, the putative short-term focus of much higher education research has been criticised. For Scott (Citation1999), this is not something that has always characterised this body of work, but developed towards the end of the 20th century. Indeed, he writes: ‘research on reasonably long timescales, with open agendas and based on reflective and critical intellectual values and practices has become less important, while customer-driven short-term investigations, more akin to management consultancy, have become more influential’ (Scott, Citation1999, p. 318). He goes on to argue that it is notable that higher education has not been seen as ‘a suitable subject for a directed research programme’ largely because ‘its connections to larger quality of life and national competitiveness projects are regarded as too oblique and nebulous’ (p.327).

Third, and in some ways related to the previous point, higher education researchers have been viewed as typically close to policymakers and thus unable to maintain a suitably critical distance within their scholarship (Kehm, Citation2015). Middlehurst (Citation2014), for example, has argued that:

the challenge facing researchers is to ensure that longer-term and deeper issues are not neglected in the rush for funding and short-term policy impact. While successful researchers engage in policy networks, they also need to maintain a critical distance from policy; and policymakers themselves must recognise that independent enquiry provides the best service for the development of both higher education and wider society. (p.1457)

Pursuing a somewhat similar argument, Papatsiba and Cohen (Citation2020) have noted the differences in sources of funding by institution type. On the basis of their analysis of impact case studiesFootnote1 submitted to the UK’s national research assessment exercise in 2014 (REF2014), they argue that the research underpinning such studies within lower status higher education institutions was commonly funded by short-term grants from higher education policy organisations. In contrast, the research underpinning impact case studies from higher status institutions was more commonly funded by research councils, with projects more likely to be of longer duration and more open-ended in nature. In this way, they suggest, institutional hierarchies have been reinforced.

Fourth, the higher education field of enquiry has been presented as fragmented, with little dialogue and cross-fertilisation between areas. This was depicted pictorially in Macfarlane’s (Citation2012) ‘higher education research archipelago’, in which he argued that there was a significant ‘sea of disjuncture’ between the researchers who inhabited ‘teaching and learning island’ (interested in, for example, assessment and feedback, doctoral supervision, learning theory and student experiences) and those located on ‘policy island’ (who focussed on topics such as globalisation, equity and access, funding and economics and internationalisation). While MacFarlane’s map was intended primarily as a provocation to the higher education research community (Macfarlane, Citation2022), it resonated with many scholars, and has been cited frequently. It also suggested that the divisions between specific areas of higher education research noted by Tight (Citation2003) almost ten years previously had largely endured.

Nevertheless, despite these various critiques, this article argues that analysis of recent data – drawn from the two most recent national assessments of research in the UK (REF2014 and REF2021), research funders’ databases, submissions to the Society for Research into Higher Education’s (SRHE) annual conference and the websites of academic journals that publish educational research – paint a rather different, and more optimistic, picture. In developing this argument, the article first considers the place of higher education research within educational studies, before discussing its location with the social sciences more broadly. It then moves on to contend that the nature of higher education research has changed over recent years, becoming increasingly international in its scope. The opportunities and challenges bound up with such developments are discussed. While the article considers the growth of interest in issues related to internationalisation, it does not, however, provide a comprehensive overview of the content of contemporary higher education research; this can be found elsewhere (e.g., Daenekindt and Huisman, Citation2020).

The article focusses largely on the state of the field since the turn of the 21st century. However, it should be noted that the data drawn upon do not always map on clearly to the same time period. For example, UK Research and InnovationFootnote2 (UKRI) grant data are available only from 2004; relevant SRHE data from only 2014; and easily searchable national research assessment data for only REF2014 and REF2021 (and thus the period from 2008 onwards, when the REF2014 cycle began). While this is a limitation of the analysis, and makes it hard to identify any particular moment of change, the data do, nevertheless, provide evidence of very similar trends over the broad period.

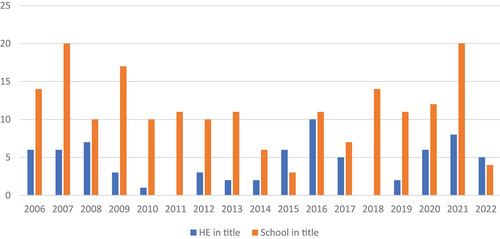

Higher Education Within Educational Studies

As suggested above, higher education research has often been critiqued for occupying a relatively marginal place within the wider discipline of educational research. However, over recent years, there is mounting evidence that higher education research is an increasingly vibrant area of enquiry. In relation to research funding, for example, data from the UKRI’s Gateway to Research on the number of grants awarded from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) () indicate that, since the turn of the century, higher education-focussed projects have regularly been funded, albeit still not to the same extent as those that are schools-orientated. The grants from these bodies are relatively large (for the arts, humanities and social sciences), and are typically expected to make a theoretical, not only empirical, contribution. Over the same period, there have also been some large investments by the ESRC, specifically in this research area. The Teaching and Learning Research Programme (TLRP), which ran from 2000 to 2008, included seven projects on widening participation, and seven on other aspects of higher education. More recently, the ESRC has funded the Centre for Global Higher Education, through a dedicated call to establish a research centre in the area of higher education – with initial funding for 2015–2020, and then additional ‘transitional’ funding from 2020–2023. (While it could be argued that these two investments are evidence of top-down priority-setting rather than the vibrancy of the area, they also demonstrate that there were a significant enough number of researchers to put together highly competitive bids for these schemes. Such investments may, however, also clearly be a contributor to the strength of the area, not merely an outcome.)

Figure 1. Number of ESRC and AHRC grants awarded by ESRC and AHRC, with higher education or school in title, 2006–2022, by date of award*

Similar patterns are evident in data from other UK funders. For example, the Nuffield Foundation has a specific funding stream on higher education and, since 2015, has funded 26 higher education-related projects. These include research on ‘Information, expectations and transitions to higher education’ (2015–19), ‘Understanding success: expectations, heterogeneity and inputs in higher education’ (2015–19), ‘Fair admission to universities in England: improving policy and practice’ (2017–20) and ‘Educational choices at 16–19 and adverse outcomes at university’ (2019–22).

Vibrancy within the field of educational studies is also evidenced in data from the most recent national research assessment exercise in the UK (REF2021). As the exercise allowed researchers to be much more selective about the work they submitted for assessment than in previous exercises (i.e., they were required to submit a minimum of one research output and, across submissions as a whole, an average of 2.5 such outputs per full-time member of staff, compared with a minimum of four submissions per staff member in REF2014), the work submitted is clearly only a relatively small proportion of the overall research conducted within the area. Nevertheless, the data do facilitate comparative judgements over time, as well as giving a good sense about what is considered, by both individuals and institutions, to be high quality work within education. As shows, the percentage of outputs submitted to the Education unit of assessment for REF2021 that focussed on higher education, at 14%, was markedly higher than the corresponding proportion in the previous exercise, at nine per cent. A similar increase was evident in relation to the impact case studies submitted for both exercises, with the number of higher education-focussed impact case studies increasing from 15% of all those submitted to the Education unit of assessment in REF2014 to 21% in REF2021 (see ). The increased vibrancy of higher education scholarship was also noted within the final report for the Education unit of assessment, which explicitly remarked on the growth in this area since REF2014 (REF2021, Citation2022).

TABLE 1. Submissions to REF Education sub-panels: outputs

TABLE 2. Submissions to REF Education sub-panels: impact case studies (ICS)

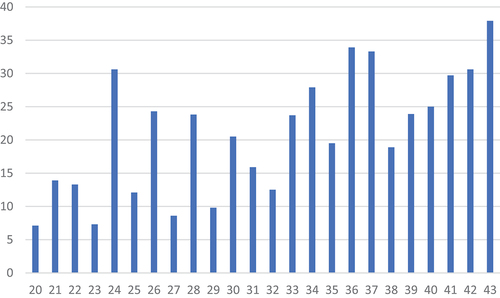

The third source of evidence for the vibrancy of higher education within educational research is individual journals. The British Journal of Sociology of Education is a well-established international journal, based in the UK, which publishes work across many areas of education from pre-school to adult education and workplace learning. A comparison of the content of articles published in this journal since the turn of the century indicates that the proportion of work focussed on higher education has seen a steady growth, with a particularly large number of articles published over the most recent period (see ). Alongside this, new higher education journals have emerged over recent years. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, for example, was launched in 2017, with the remit of publishing articles that engage explicitly with topical policy questions and significant areas of higher education policy development.

Figure 2. Percentage of articles focussing on higher education published in the British Journal of Sociology of Education, by issue number: 20 (1999) to 43 (2023)

Evidence from these three sources – research funding bodies, the UK’s national research assessment exercise, and education journals – indicates that higher education research now occupies an important place within the wider educational research landscape, and has grown in vibrancy over the past ten to twenty years. Moreover, it appears to have successfully addressed some of the weaknesses identified by scholars a decade or so ago, which were outlined above. The success of higher education researchers in securing grants from the ESRC, AHRC, Nuffield Foundation and other funding bodies suggests that they are no longer dependent on the short-term grants from policy organisations noted by Middlehurst (Citation2014), enabling the exploration of issues in more depth across longer timescales. Reliance on these sources of funding – rather than short-term, smaller, more ‘consultancy-like’ awards from policy organisations – can also facilitate the ‘critical distance’ between researchers and policymakers advocated by Middlehurst. Nevertheless, analysis of the UKRI grants, by institution and geographical location (), demonstrates that such shifts are not benefitting all researchers equally – with those located in Russell Group institutions and in England dominating. Here, despite the vibrancy of the area, some of the same hierarchies as observed by Papatsiba and Cohen (Citation2020) are played out.

TABLE 3. Type and location of principal investigator’s institution for ESRC and AHRC research grants awarded on higher education, 2006–2022

All three sources of evidence discussed above also indicate that the ‘absence of theory’ (Ashwin, Citation2012; Tight, Citation2014) is no longer an accurate characterisation of the field. As noted above, UKRI grants typically require grant-holders to make a theoretical contribution, as well as an empirical one, through their work, while a robust conceptual framework is obviously important to work published in high status journals (such as the British Journal of Sociology of Education) and likely to be a consideration in work selected for submission to REF2021, given the relatively low number of submissions required per individual (see above). This analysis reflects, to some extent, the conclusions reached by Macfarlane (Citation2022) in his review of articles published in the journal Higher Education Research and Development between 1982 and 2022. He notes a significant shift in the focus of articles over time, away from a pragmatic emphasis on problems and how to solve them to a more theoretically-informed critical analysis. This is further evidence of a developing area of enquiry, more interested in conceptual questions and longer-term issues rather than short term responses to immediate problems within policy or practice. There has perhaps been less change with respect to the disjuncture within higher education research that MacFarlane noted in 2012 – between scholarship on teaching and learning, on the one hand, and on policy, on the other hand. Although many researchers are interested in the links between the two – for example, how policies related to equitable access to higher education can impact on processes of teaching and learning (e.g., Hayes, Citation2019) – studies have also pointed out the increasing specialisation in the field and an associated decline in topic diversity, a trend common across modern science (Daenekindt and Huisman, Citation2020).

The vibrancy of higher education research can be explained by factors at a variety of levels. First, despite the points above about the ‘critical distance’ between researchers and policymakers, it seems very likely that much higher education research is related to the wider national policy context in the UK (and other parts of the world), in which politicians and policymakers have shown a high level of interest in the higher education sector, and taken up an increasingly interventionalist stance (Ashwin and Clarke, Citation2022). Researchers are likely to be, in part, responding to this political prioritisation. The ongoing massification of higher education in the UK, with around 50% of each cohort going on to degree-level study, may also have driven research activity in this area – with researchers cognisant of the importance of the sector to many people’s lives. As scholars have noted previously, higher education research is also encouraged at the institutional level – not only through the work of academic development units (or similar) – but also through the funding made available by universities to their academic staff to better understand their student populations and/or to pursue pedagogical research, with the aim of improving processes of teaching and learning (Cotton et al., Citation2018). Often these are bound up quite closely with the wider policy environment: a desire to use research to improve ‘the student experience’ (Sabri, Citation2011) may be underpinned by market imperatives – for example, to improve an institution’s performance in the National Student Survey.Footnote3 Increased support from professional organisations is likely to have also played a role in the stimulation of higher education research. For example, the network of Early Career Higher Education Researchers was formed in 2011 and offers a range of developmental opportunities for those at the start of their academic careers, as well as a means of bringing early career scholars together. Finally, the ease and low cost of access to research participants (i.e., students and higher education staff) may also have driven enquiry in this area, in a context where research funding has become extremely competitive.

Higher Education Within Social Sciences More Generally

The vibrancy of higher education research is also evident outside the disciplinary area of education. While higher education has long been categorised as an ‘open access’ field (Harland, Citation2012), pursued as an area of enquiry within psychology, sociology, political science and history, for example (Daenekindt and Huisman, Citation2020), recent years have witnessed further disciplinary spread. This is perhaps most evident within the discipline of human geography. An analysis of articles published within the prestigious and generalist human geography journal, Geoforum, shows a very significant increase in interest in higher education. Indeed, prior to 2002, only two articles focussed on higher education had been published in the journal: one in 1979 (on postgraduate research students in UK universities) and another in 1994 (on school type and the geography of British university applications). However, since 2012, a significant number of articles have appeared each year in the journal – with a peak of six in 2018.

This publication profile has been mirrored, to some extent, by structural change within the Royal Geographical Society – the main professional association for UK-based geographers. In the late 1970s, a Higher Education Learning Working Party/Study Group was established within the Royal Geographical Society. From the turn of the 21st century, this underwent significant change, becoming the Higher Education Research Group in 2002, and then the Geography and Education Research Group in 2019 (Healey and West, Citation2022; Healey et al., Citation2022). Healey and West (Citation2022) explain that one of the reasons for the change of name was to recognise the considerable body of research on higher education that was being conducted by geographers that was no longer focussed on applied pedagogy. Indeed, the emphasis on ‘learning’ in the original name was seen as barrier to participation by this new group of scholars who were interested in the various spatial processes enacted within and by higher education (ibid.).

Alongside the increasing interest of geographers in the area of higher education, scholars from other disciplines have continued work in this area. Again, REF2021 data can be used to illustrate this point. As indicates, impact case studies that were focussed on higher education were submitted across a relatively large number of units of assessment – from one in each of Politics and International Studies, Psychology, Psychiatry and Neuroscience, and Geography, to nine in Sociology. Examples include: ‘Opening up digital fieldwork technology to staff and students in further and higher education’ (Geography, Chester); ‘Healthy universities: a whole system approach to improving health, wellbeing and sustainability in higher education’ (Social Work, Central Lancashire); ‘Tackling sexual harassment and violence in higher education’ (Sociology, Brunel), and ‘School of hard knocks; building inclusion for refugees and forced migrants in higher education’ (Sociology, University of East London). It is striking that the total number of impact case studies from these units constitutes over a third of all those with a higher education focus (including the 47 from the Education unit of assessment, noted in ).

TABLE 4. REF2021 impact case studies with HE focus, submitted to units of assessment other than education

Evidence such as this suggests that, despite some indications that the professional identity of higher education researchers is strengthening – for example, in relation to the emergence of the network of Early Career Higher Education Researchers – higher education research remains an ‘open access’ field (Harland, Citation2012). Indeed, the increase in interest in higher education from within human geography demonstrates an apparent widening of ‘contributor disciplines’. While the significant interest in higher education by psychologists, sociologists and researchers from business schools is likely underpinned by the same factors that explain interest within educational research (see previous section), the heightened interest among geographers may be related to changes in both the student and staff population in UK higher education. The increasing number of international students in the UK has resulted in a corresponding increase in the number who remain in the UK – as postgraduate researchers and then academic staff – keen to research their own experiences of migration and internationalisation (Waters and Brooks, Citation2021). Within geography, examples include Prazares et al.'s (Citation2017) work on the importance of place in the decision-making processes of international students, Kris Lee’s (Citation2020) exploration of the use of social media by international students, and Jihyun Lee’s (Citation2022) analysis of the employment desires of international students.

Concern is sometimes raised by scholars about the ‘open’ nature of higher education research and its porous boundaries. Tight (Citation2014), for example, notes the lack of interaction between scholars approaching the same issue from a different disciplinary perspective. However, the increase in cross-disciplinary citation with respect to higher education (particularly notable in relation to the scholarship on international students, mentioned above), suggests that this ‘openness’ is to be welcomed – as a means of facilitating new collaborations, and offering new perspectives and theoretical frames. Moreover, the literature has perhaps also over-stated the extent to which (higher) education is different from other social sciences in its porosity. Indeed, Garsforth and Kerr (Citation2011) have argued that the social sciences are all ‘restless disciplines’, ‘characterised by fuzzy boundaries, epistemological pluralism and ever-changing methods, theories and research fields’ (p.659).

Higher Education as Increasingly International in Scope

Alongside the growth in higher education as an area of scholarly enquiry has been an increasing emphasis, within this body of work, on issues related to internationalisation. This can again be evidenced in relation to both submissions to the national research assessment exercise and research funding awards. The REF2021 report from the Education unit of assessment noted, in its section on higher education, that ‘Internationalisation and international student and staff mobility were a strong feature, often in comparative studies’ (REF2021, Citation2022, p. 160). Furthermore, 14 of the 47 higher education-focussed impact case studies submitted to the Education unit of assessment covered countries outside of the UK. Examples include: ‘Safeguarding academic freedom in the nations of the Council of Europe’; ‘Enhancing gender equality in national and international educational contexts’; and ‘Syrian academics in exile: enhancing well-being and identity, building research capacity, and improving higher education in conditions of conflict and displacement’.

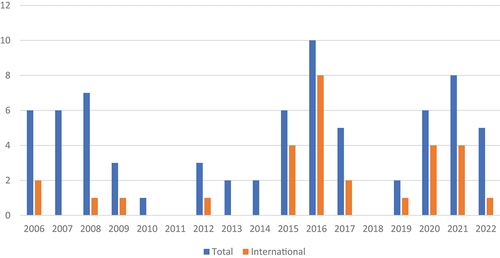

In relation to research funding, shows the number of higher education-focussed grants from the ESRC and AHRC, between 2006 and 2022, which also had an international orientation (evident in the title of the project). While some internationally-oriented projects were funded in the early part of this period, they became more common from 2015 onwards. As mentioned above, the ESRC also made a significant investment in this area from 2015, by funding the Centre for Global Higher Education in response to a dedicated research centre call (funded for an initial period from 2015–20, and then given transitional funding from 2020–23).

Figure 3. Number of ESRC and AHRC grants awarded on higher education and with an international focus, 2006–2022, by date of award*

This increasing focus on international issues can also be seen within the work of professional organisations. For example, the research domain that received the largest number of submissions for the UK-based Society for Research into Higher Education’s (SRHE) annual conference in 2022 was that focussing on ‘International Contexts and Perspectives’ (see , below). This contrasts with only 9% in 2014 (see ), when this specific domain was first introduced to the SRHE conference. It is also notable that, prior to 2014, this was presumably not seen as a large enough area of enquiry to justify identification as a separate research domain (SRHE conference data extend back to 2011).

TABLE 5. Society for Research into Higher Education conference submissions, 2014 and 2022

These trends, evidenced in contemporary data from the UK, mirror observations that have been made by others who have analysed the field of higher education studies. For example, on the basis of their analysis of articles on higher education published between 1991 and 2018, Daenekindt and Huisman (Citation2020) note that studies of international student mobility, specifically, have become increasingly prominent in the literature. Similarly, Tight (Citation2021), who conducted an analysis of articles on higher education with the Scopus database, has argued that globalisation and internationalisation are amongst the most discussed and researched aspects of higher education in the past two decades. Such trends have also been documented within professional associations. Indeed, Kehm (Citation2015) points to the increase in members of the Consortium of Higher Education Researchers (perhaps the most high-profile international association for those researching in this area) who have recorded an interest in internationalisation as a thematic area.

This shift in focus, over time, towards issues associated with internationalisation and globalisation, can be explained by various factors operating at different scales. As Kwiek (Citation2021) and numerous others have observed, within educational research, in common with many other areas of enquiry, we have witnessed the emergence of ‘global science’ and significant trends towards cross-national collaborations across the world. Working with partners located outside of a researcher’s own nation, and pursuing topics of interest beyond a single nation-state has become normalised. These trends have been reinforced by the actions of regional and national funding bodies. For example, in the UK, while value to the domestic tax-payer is an important consideration for publicly-funded grant awarding bodies, specific funding streams have provided a strong incentive to higher education researchers (along with their colleagues in other fields) to collaborate with colleagues outside the UK, to address issues of international concern. One example of this is the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), which was established in 2016, with the aim of promoting the economic development and welfare of low income countries by funding international research. This has facilitated a considerable number of international studies that have focussed on some aspect of higher education and explains much of the increase in internationally-orientated studies (funded through UKRI, which administered the GCRF grants) evident in . In addition, for UK-based scholars, the European Union has been an important driver of internationally-focussed research – through both the cross-national consortia necessary to respond to calls within the European Commission’s programme of research, and the (implicit) expectation of work that speaks to international issues within its fellowship programme (administered through the European Research Council).

Institutional factors are also significant. Indeed, in many UK universities, researchers are strongly encouraged and/or incentivised to collaborate with colleagues located in other nation-states, and to pursue research topics that are not only of domestic interest. To some extent, this is bound up with processes of marketisation, as institutions clamour to be perceived as a ‘World Class University’ (Huisman, Citation2008) – in the belief that this will help ensure future sustainability (through attracting both staff and students, for example). Indeed, many UK universities (particularly larger ones, with greater resources to draw upon) offer dedicated funding for researchers to develop links with colleagues in particular parts of the world, with the aim of generating co-authored publications (which are valued in various international assessments such as the Times Higher World University Rankings) and preparing the ground for applications for external funding (Brooks et al., Citation2021). At the individual level, beyond responding to the norms and incentives within the wider international, national and institutional context, as discussed above, researchers are increasingly bringing their own international contacts to their research endeavours. Larner (Citation2015) contends that, because of the growing internationalisation of the academic labour market (in the UK and elsewhere), a rising number of researchers now have multiple national affiliations and relationships. She conceptualises such individuals as ‘academic intermediaries’, diasporic academics who ‘have become central to the creation of global knowledge networks’ (p. 197). They are valued highly by their institutions for the contacts they bring, but also have strong personal motivation to utilise their international links – as they perceive that global networks are increasingly important to successful careers (ibid.)

In many ways, the increasing internationalisation of higher education research can be seen as a positive development – a humanistic endeavour that avoids the insular national focus which has historically characterised a substantial proportion of UK higher education research. Nevertheless, there are also various threats – to this potential humanism – bound up with the form of internationalisation that is pursued. First, it is notable that ostensibly international journals and international editorial boards are often dominated by Western scholars – a pattern repeated in relation to the authorship of individual publications on international issues within higher education (Mwangi et al., Citation2018; Waters and Brooks, Citation2021). For example, Tight’s (Citation2021) analysis of articles on higher education in the Scopus database indicated that UK-based authors dominated in work that focussed on processes of internationalisation, while their US counterparts were dominant with respect to articles on globalisation. Tight suggests that this geographical imbalance can be explained to some extent by the similar pre-eminence of these two nations in the recruitment of international students (presumably because of the assumed relevance of scholarship in this area to policy and practice). He observes ‘Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is those who stand to benefit most from internationalisation in higher education who are doing most of the research, while also often ignoring or underplaying the power issues involved’ (p.56) and goes on to suggest that higher education research is arguably less globalised and/or internationalised than the systems and institutions it studies. The reliance on English as the lingua franca of academic publishing is obviously also an important explanatory factor (Adriansen et al., Citation2022).

Second, the focus of articles on this topic is often far from ‘international’. Indeed, various scholars have argued that Western perspectives are often privileged (Mwangi et al., Citation2018). Writing with respect to international student mobility (ISM) specifically, Kondakci et al. (Citation2018) contend that ‘research on patterns of ISM and the dynamics shaping these patterns has been dominated by studies reflecting a Western orientation, discourse and understanding’ (p.517). Moreover, Brooks and Waters (Citation2022) have argued that while the word ‘international’ implies ‘many countries’ and a global scope, in fact ‘international has often come to indicate a highly circumscribed geographical focus, and this is despite a notable diversity in the foci of discussions around ISM (and diversity in where students are choosing to study) over the past decade’ (p.530). Indeed, discussion of the ‘international’ within higher education research can represent something of a paradox, potentially leading to an increased diversity of perspectives and, at the same time, a narrowing Westernisation and Anglicisation of higher education (Saarinen and Ennser-Kananen, Citation2020).

Finally, the way in which ‘international space’ has been conceptualised can also be seen as in some ways limited – tending to understand it as something closely related to nation-states, and often bi-lateral in nature, rather than adopting a more global, multi-national, transnational or cosmopolitan optic (Brooks and Waters, Citation2022). This is evidenced in the large proportion of studies that focus on students moving between one country and another (e.g., Waters, Citation2006; Yang, Citation2016); students from multiple sending countries moving to one receiving country (e.g., Robertson, Citation2013; Tannock, Citation2018); or one sending and multiple receiving countries (e.g., Fong, Citation2011). Thus, within this field of research, an implicit methodological nationalism (Wimmer and Glick Schiller, Citation2002) continues to prevail, alongside an implicit rejection (in recent scholarship) of those who have argued that globalisation has diminished the national as the ‘natural’ scale of politics and policy (e.g., Ozga and Lingard, Citation2007) (see Brooks and Waters, Citation2022 for further discussion). As I have argued previously:

The limits to the specific ways in which the concept of ‘international’ is deployed need to be exposed and addressed (through, for example, greater engagement with other (sub-) disciplinary perspectives, and with scholars from outside the Global North). Otherwise, there is a danger that scholarship is not only missing important alternative geographies of ISM, but is also inadvertently perpetuating the myth that ‘the international’ can be equated to Anglophone, Western locations and thereby enacting a form of neo-colonialism (Brooks and Waters, Citation2022, p. 531).

Conclusion

This article has sought to demonstrate that, within the UK at the time of writing, higher education studies is in a relatively strong place – in relation to both the wider areas of educational studies and the social sciences more generally. This is evidenced by the increasing number of publications with a higher education focus, and the success of scholars working in this area in securing funding for longer-term, more conceptually-orientated projects (such as those supported by the UK’s national funding bodies), not only for shorter-term pieces of work in response to particular policy needs. Indeed, in many ways the landscape of UK higher education research now appears significantly different from that described by scholars in the 1990s and early part of the twenty first century, which emphasised the relatively atheoretical nature of much higher education research, its short-term nature, and its dependence on the agenda of policymakers (Kehm, Citation2015; Middlehurst, Citation2014; Scott, Citation1999).

Nevertheless, the foundations upon which it rests are not necessarily strong. As the data above have illustrated, there is evidence of stratification across the field, with those from higher status universities, and based in England, over-represented amongst the principal investigators of higher education-focussed UKRI grants. Moreover, as Jones (Citation2022) has articulated clearly in his book, Universities Under Fire, higher education per se within the UK has come under increasing attack from policymakers while, across the world, higher education systems are facing a period of acute instability as a result of, inter alia, the COVID-19 pandemic, geo-political tensions, inflation and economic instability (Hazelkorn et al., Citation2022). Moreover, it is not clear that educational studies is in the same position as its higher education counterpart. Indeed, the report from the REF2021 education sub-panel noted the decline in external research income reported across all education submissions: from £58 million for REF2014 to £55 million for REF2021 – a decline that is obviously even starker in real terms (REF2021, Citation2022). Moreover, analysis conducted by James (Citation2022) indicates that educational research receives significantly less funding than many other cognate subject areas. It is also the case that, despite the significant interest in higher education as an object of study across many social sciences, discussed above, it remains largely absent from institutional structures outside of education departments. There are, for example, very few higher education-focussed research centres in UK universities outside departments of education or educational development units – the ‘Higher Education and Social Inequality’ research grouping within Durham University’s Department of Sociology is a rare exception.

There are also a number of substantive challenges that those researching higher education – whatever their home discipline – will need to face. As alluded to in the previous section of the article, while the ‘international’ focus of higher education research has grown considerably over recent decades, it needs to address more adequately various post-colonial legacies, through paying greater attention to the location of researchers and the substantive focus of research. This may be a challenge in the UK and other parts of the world that have experienced significant growth in populism and nationalism – with funding bodies increasingly expected to demonstrate the value of research to the UK government’s particular political priorities. This can be seen, for example, in the government’s announcement in February 2022 of the end to the ‘Global Challenges Research Fund’ in its current format (linked to the significant reduction in the budget for Official Development Assistance), which, as discussed above, has in the past facilitated a considerable number of higher education-focussed projects with a strong international orientation. The possible withdrawal of the UK from the European Union’s Horizon funding programme (at the time of writing) may also impede collaborative international research – particularly with European partners. Thus, while the current vibrancy of higher education studies is, in many ways, for those of us working in the area, to be celebrated, it needs to address quite urgently the intellectual and political challenges bound up with its own objects of study and to continue to make the case for the importance of higher education research – and particularly that which has an international orientation – in a turbulent policy context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 An impact case study is a document describing the impact of research undertaken within the submitting unit. It also contains information about the underpinning research. In REF2014, it contributed to 20% of an institution’s overall profile. In REF2021, this increased to 25%.

2 UKRI is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the UK Government’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. It brings together the seven disciplinary research councils, Research England, which is responsible for supporting research and knowledge exchange at higher education institutions in England, and the UK’s innovation agency, Innovate UK.

3 The National Student Survey is an annual survey, launched in 2005, of all final year undergraduate degree students at institutions in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom.

References

- Adriansen, H., Juul-Wiese, T., Madsen, L., Saarinen, T., Spangler, V. and Waters, J. (2022) Emplacing English as lingua franca in international higher education: a spatial perspective on linguistic diversity, Population, Space and Place ( online advance access).

- Ashwin, P. (2012) How often are theories developed through empirical research into higher education?, Studies in Higher Education, 37(8), 941–95510.1080/03075079.2011.557426

- Ashwin, P. and Clarke, C. (2022) The Office for Students, expertise and legitimacy in the regulation of higher education in England, HEPI blog. Available at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2022/09/04/the-office-for-students-expertise-and-legitimacy-in-the-regulation-of-higher-education-in-england/ ( Accessed 25/11/22)

- Brooks, R., Erdogan, A. and Sahin, B. (2021) Higher Education Partnerships Between the UK and Turkey: Baseline Research, (London, British Council)

- Brooks, R. and Waters, J. (2022) Partial, hierarchical and stratified space? Understanding ‘the international’ in studies of international student mobility, Oxford Review of Education, 48(4), 518–53510.1080/03054985.2022.2055536

- Cotton, D., Miller, W. and Kneale, P. (2018) The Cinderella of academia: is pedagogic research undervalued in UK research assessment?, Studies in Higher Education, 43(9), 1625–163610.1080/03075079.2016.1276549

- Daenekindt, S. and Huisman, J. (2020) Mapping the scattered field of research on higher education. A correlated topic model of 17,000 articles, 1991–2018, Higher Education, 80(3), 571–58710.1007/s10734-020-00500-x

- Fong, V. (2011) Paradise Redefined. Transnational Chinese Students and the Quest for Flexible Citizenship in the Developed World, (Stanford, California, Stanford University Press)

- Garsforth, L. and Kerr, A. (2011) Interdisciplinarity and the social sciences: capital, institutions and autonomy, The British Journal of Sociology, 62(4), 657–67610.1111/j.1468-4446.2011.01385.x

- Harland, J. (2012) Higher education as an open-access discipline, Higher Education Research and Development, 31(5), 703–71010.1080/07294360.2012.689275

- Hayes, A. (2019) Inclusion, Epistemic Democracy and International Students: The Teaching Excellence Framework and Education Policy, (Basingstoke, Palgrave McMillan)

- Hazelkorn, E., Locke, W., Coates, H. and de Wit, H. (2022) Unprecedented challenges to higher education systems and academic collaboration, Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 6(2), 125–12710.1080/23322969.2022.2103883

- Healey, R., France, D., Hill, J. and West, H. (2022) The history of the Higher Education Research group of the UK Royal Geographical Society: the changing status and focus of geography education in the academy, Area, 54(1), 6–1410.1111/area.12685

- Healey, R. and West, H. (2022) Re-naming and re-framing: evolving the “Higher Education Research Group” to the “Geography & Education Research Group”, Area, 54(1), 2–510.1111/area.12759

- Huisman, J. (2008) World-Class Universities, Higher Education Policy, 21(1), 1–410.1057/palgrave.hep.8300180

- James, D. (2022) Personal communication. [Research currently being written up.]

- Jones, S. (2022) Universities Under Fire. Hostile Discourses and Integrity Deficits in Higher Education, (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan)

- Kehm, B. (2015) Higher education as a field of study and research in Europe, European Journal of Education, 50(1), 60–7410.1111/ejed.12100

- Kondakci, Y., Bedenlier, S. and Zawacki-Richter, O. (2018) Social network analysis of international student mobility: uncovering the rise of regional hubs, Higher Education, 75(3), 517–53510.1007/s10734-017-0154-9

- Kwiek, M. (2021) What large-scale publication and citation data tell us about international research collaboration in Europe: changing national patterns in global contexts, Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2629–264910.1080/03075079.2020.1749254

- Larner, W. (2015) Globalising knowledge networks: universities, diaspora strategies and academic intermediaries, Geoforum, 59, 197–205 10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.10.006

- Lee, K. (2020) “I Post, therefore I Become #cosmopolitan ”: the materiality of online representations of study abroad in China, Population, Place and Space, 26(3), 310.1002/psp.2297

- Lee, J. (2022) When the world is your oyster: international students in the UK and their aspirations for onward mobility after graduation, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 20(3), 277–29010.1080/14767724.2021.1904209

- Macfarlane, B. (2012) The higher education research archipelago, Higher Education Research and Development, 31(1), 129–13110.1080/07294360.2012.642846

- Macfarlane, B. (2022) A voyage around the ideological islands of higher education research, Higher Education Research and Development, 41(1), 107–11510.1080/07294360.2021.2002275

- Middlehurst, R. (2014) Higher education research agendas for the coming decade: a UK perspective on the policy–research nexus, Studies in Higher Education, 39(8), 1475–148710.1080/03075079.2014.949538

- Mwangi, C., Latafat, S., Hammond, S., Kommers, S., Thoma, H., Berger, J. and Blanco-Ramirez, G. (2018) Criticality in international higher education research: a critical discourse analysis of higher education journals, Higher Education, 76(6), 1091–110710.1007/s10734-018-0259-9

- Ozga, J. and Lingard, B. (2007) Globalisation, education policy and politics, In B. Lingard and J. OzgaEds, The RoutledgeFalmer Reader in Education Policy and Politics, (London, Routledge), pp. 65–82

- Papatsiba, V. and Cohen, E. (2020) Institutional hierarchies and research impact: new academic currencies, capital and position-taking in UK higher education, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(2), 178–19610.1080/01425692.2019.1676700

- Prazares, L., Findlay, A., McCollum, D., Sander, K., Musil, E., Krisjane, Z. and Apsite-Berina, E. (2017) Distinctive and comparative places: alternative narratives of distinction within international student mobility, Geoforum, 80, 114–122 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.02.003

- REF2021 (2022) Overview report by Main Panel C and Sub-panels 13 to 24. Available online at (Accessed 25/11/22): https://www.ref.ac.uk/media/1912/mp-c-overview-report-final-updated-september-2022.pdf

- Robertson, S. (2013) Transnational Student-Migrants and the State: The Education-Migration Nexus, (London, Palgrave Macmillan)

- Saarinen, T. and Ennser-Kananen, J. (2020) Ambivalent English: what We Talk About When We Think We Talk About Language, Nordic Journal of English Studies, 19(3), 11510.35360/njes.581

- Sabri, D. (2011) What’s wrong with ‘the student experience’?, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(5), 657–66710.1080/01596306.2011.620750

- Scott, P. (1999) The research-policy gap, Journal of Education Policy, 14(3), 317–33710.1080/026809399286378

- Tannock, S. (2018) Educational Equality and International Students. Justice Across Borders, (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan)

- Tight, M. (2003) Researching Higher Education, (MaidenheadOpen University Press)

- Tight, M. (2014) Discipline and theory in higher education research, Research Papers in Education, 29(1), 93–11010.1080/02671522.2012.729080

- Tight, M. (2021) Globalization and internationalization as frameworks for higher education research, Research Papers in Education, 36(1), 52–7410.1080/02671522.2019.1633560

- Waters, J. L. (2006) Geographies of cultural capital: education, international migration and family strategies between Hong Kong and Canada, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 31(2), 179–19210.1111/j.1475-5661.2006.00202.x

- Waters, J. and Brooks, R. (2021) Student Migrants and Contemporary Educational Mobilities, (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan)

- Wimmer, A. and Glick Schiller, N. (2002) Methodological nationalism and beyond: nation–state building, migration and the social sciences, Global Networks, 2(4), 301–33410.1111/1471-0374.00043

- Yang, P. (2016) International Mobility and Educational Desire: Chinese Foreign Talent Students in Singapore, (New York, Palgrave Macmillan)