Abstract

The aim of this study is to challenge the widely-held assumption that members of the general board of a multinational corporation will not be aware of what is happening on the shop floor in their affiliates in other parts of the world, in particular when such actions have profound potential moral and/or legal implications. This assumption of ‘corporate ignorance’ is refuted by a case study documenting the information that members of the general board of a Dutch multinational received about crimes against humanity that were committed during the 1970s in Argentina, and, more specifically, in and around their local affiliate where workers were forcefully abducted and disappeared. In this historical case, members of the general board appear to have been fully aware of these crimes while knowingly ignoring and remaining indifferent to the involvement of their local affiliate. In hindsight, the multinational corporation they represented can, therefore, be viewed as ‘silently complicit’.

Introduction1

In a globalising world, multinational corporations tend to extend their domestic activities to other countries through acquisitions, joint ventures, and mergers. In the process of such expansion, they often face problems in dealing with the societal contexts and enterprise traditions in which their local affiliates are embedded (Harzing & Sorge, Citation2003, p. 190). In order to be economically viable, they must be able to comprehend, adapt, and effectively respond to the social, legal, and political environment of their affiliates. In actual practice, this means that multinational corporations may have to deal not only with corrupt business partners, officials, and politicians but also with violations of fundamental human rights, particularly in countries with non-democratic or even brutally repressive regimes (Rodriguez et al. Citation2006, p. 743). In developing business relations, multinational corporations run the political risk of becoming involved in corruption and/or international crimes – war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity – committed by others. Non-governmental organisations report weekly on how multinational corporations are contributing to and/or profiting from the commission of these crimes (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre).2 At the same time, these corporations face normative expectations with respect to human rights. These expectations also concern affiliates of these corporations operating in other countries. A business corporation may already be complicit if it ‘knowingly ignores human rights abuses committed by an entity associated with it’ (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Citation2004, p. 18). In order to prevent corporate complicity in human rights violations and crimes against humanity, business corporations are currently expected to comply with the United Nations Guiding Principles and to monitor and assess both the actual and potential impact of their corporate activities on human rights.3 Obviously, this has not always been the case.

In this article, I am concerned with a historical case of what, today, might be considered as corporate complicity in crimes against humanity. The case concerns the former Dutch multinational corporation Akzo,4 and its Argentinian affiliate Petroquímica Sudamericana. The research question is whether, by current standards, this multinational corporation, through its local affiliate, can be viewed as having been complicit in the commission of crimes against humanity during the military dictatorship in Argentina, 1976–1983.

Currently, the courts in Argentina are investigating the role of corporations in the abduction, killing, and disappearance of workers as well as trying to find ways of holding individual businessmen accountable for complicity of their company in these crimes. International criminal law does not offer much guidance as, in its current state, ‘the legal framework for holding corporations and their individual agents criminally responsible … is poorly developed and, even more so, poorly enforced’ (Fauchald & Stigen, Citation2009, p. 1035). One reason why assigning criminal responsibility for complicity in international crimes is complicated is the requirement of awareness that corporate conduct might aid in the commission of these crimes. Attributing corporate complicity requires some form of knowledge, i.e. an awareness or conscious disregard of information that such crimes are (to be) committed and that the perpetrators of these crimes may have been enabled or facilitated by the conduct of the company. In actual practice, it is difficult – if not impossible – to prove that business representatives actually knew that their corporation was or could become involved in the commission of crimes against humanity (Van der Wilt, Citation2013, p. 64). And it seems that ‘the larger the corporate entity and the more complicated the network of responsibilities and lines of communication, the more difficult it becomes to prove individual involvement sufficient to warrant individual criminal responsibility’ (Brants, Citation2007, p. 319). As a result, business representatives and, especially, high level corporate executives, have rarely been held accountable for their corporation’s complicity in the commission of international crimes.

In order to explain this de facto impunity, it is often assumed that members of the general board of management of large and complex multinational corporations will be unaware of any misconduct on the shop floor of their local affiliate, unless they deliberately ‘make sure that nothing gets reported that they should but would rather not know about’ (Brants, Citation2007, p. 317). In general, however, the more remote from the centre of decision making the misconduct takes place, the less likely the general board is to know about it. The information will remain at a lower level in the organisation and fail to come to the attention of the general board (Van der Wilt, Citation2013, p. 71). Especially in a multinational corporation with a hierarchical and differentiated management structure, the general board will function at such a geographical, substantial, and informative distance that ‘ignorance will most likely be the outcome’ (Hornman, Citation2016, p. 246, 504).

The aim of this study is to question this assumption of ‘corporate ignorance’ by documenting the information that members of the general board of a Dutch multinational received of the crimes against humanity that were committed during the 1970s in Argentina, and, more specifically, in and around their affiliate where workers were forcefully abducted and disappeared. In exploring this case, it will be shown that members of the general board and local representatives of the multinational appear to have been fully aware while knowingly ignoring and remaining indifferent to the involvement of their local affiliate in the crimes against humanity that were being committed during the military dictatorship.

Corporate complicity

The issue of corporate complicity in crimes against humanity was first, and most dramatically, raised in 1946 when, in preparation for the war crimes trial at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, ‘criminal charges against corporations were considered entirely permissible, though ultimately not used’ (Bush, Citation2009, p. 1095). Instead, only individual owners and executives of German enterprises were tried for the complicity of their company in war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity (including the use of slave labour) committed by the Nazi regime (Bush, Citation2009, p. 1096).

In the field of business history (Berghoff, Citation2001), corporate complicity in crimes against humanity is a relatively new topic. Traditionally, the main concern of business historians has been with the development of corporations, their organisational structure, and corporate culture, patterns of innovation, production, and distribution (Amatori & Jones, Citation2003; Jones & Zeitlin, Citation2008). Also of interest were relations between business and politics, i.e. between corporations and political institutions (political parties, parliaments, governments), their political activities, and their social impact. (Friedman & Jones, Citation2011) With the exception of research into the involvement of business corporations in the crimes of the Nazi regime (Turner, Citation1985; Allen, Citation2002; James & Tanner, Citation2002; Feldman & Seibel, Citation2004), relatively little has been written about the complications and dilemmas of doing business under the extreme political circumstances of totalitarian regimes – for example, a military dictatorship (Wilkins, Citation2004; Kobrak, Hansen & Kopper, Citation2004; Bucheli, Citation2008) – in which business corporations were facing the risk of becoming complicit in crimes against humanity committed by these repressive regimes.

In studying corporate involvement in the Holocaust and other crimes against humanity committed by the Nazi regime, business historians are using a variety of concepts. For example, the involvement of business leaders in these crimes tends to be qualified in terms of implication, collaboration, cooperation, or participation, etc.; while, in this research, the focus tends to shift to ‘the culpability of individual companies and their leaders’ (Berghahn, Citation2004). This is unfortunate, since culpability is a legal issue that should be left to lawyers, legal scholars, and the courts. Business historians should restrict themselves to ‘the role that business people and enterprises played’ in the Holocaust and other crimes against humanity (Berghoff, Kocka and Ziegler, Citation2013, p. 1).

In these studies, the concept of corporate or business complicity has occasionally been used (Berghahn, Citation2004; Hayes, Citation2004; James, Citation2001), albeit without defining it. This may create confusion because in criminal law the concept of complicity has a specific and technical meaning which ‘does not correspond to the concept of ‘business complicity’ in the study of gross human rights violations where it is being used ‘in a much richer, deeper and broader fashion than before’ (ICJ, Citation2008, p. 3).

In this study, the term corporate or business complicity is, therefore, ‘not used in the legal sense denoting the position of the criminal accomplice, but rather in a … colloquial manner to convey the connotation that someone has become caught up and implicated in something that is negative and unacceptable’ (ICJ, Citation2008, p. 3). In this manner, complicity does not refer specifically to individual corporate executives but rather to both ‘a company entity and/or company official’ (ICJ, Citation2008, p. 4) as well as to corporate acts of commission or omission that appear ‘morally dubious’ (James, Citation2001, p. 2).

Following Clapham (Citation2001), a distinction can be made between direct complicity (e.g. when a corporation is actually assisting in the commission of crimes against humanity), indirect complicity (e.g. when a corporation is benefitting from the commission of these crimes), and silent complicity (e.g. when a corporation is ignoring the commission of these crimes). The notorious cases of Flick (Priemel, Citation2012), I.G. Farben (Hayes, Citation1987; Lindner, Citation2008), and Krupp (Abelshauser, Citation2002), but also multinationals like Ford and General Motors (Billstein et al., Citation2004; Reich, Citation2004; Turner, Citation2005) or IBM (Heide, Citation2004; Black, Citation2012) concern forms of direct complicity like enabling or assisting in the Holocaust (Bush, Citation2009; Ramasastry, Citation2002). From these examples, it is clear that many business leaders ‘were unwilling to avoid complicity in the crimes of the Third Reich’ (Nicosia and Huener, Citation2004, p. 5). On the contrary, their companies were active partners of the Nazi regime (Feldman, Citation2001) and willingly cooperated or assisted in the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity (Berghoff, Citation2015, p. 25).

Other companies, like Deutsche Bank (James, Citation2001) and Dresdner Bank (Henke, Citation2006), were not directly involved in the crimes of the Nazi regime but indirectly complicit by benefitting from them. Their claim that they were simply doing ‘business as usual’ under the extraordinary circumstances of Nazi Germany was, therefore, ‘inherently implausible, for there was nothing very usual about German business at that time’ (Henke, Citation2006, p. 213).

Although most companies were neither directly nor indirectly involved in the crimes against humanity of the Nazis, many businessmen and corporations acted as ‘silent partners’ of the regime (Berghoff, Kocka & Ziegler, Citation2013, p. 11). This also applied to business leaders of companies in the occupied territories doing business with Nazi Germany. A case in point is Unilever (Wubs, Citation2008). After its business leaders met with Adolf Hitler in 1933, they anticipated and accommodated the policies of the Nazis and supported their war effort by supplying fat, food, and soap to the German home front. Whereas Wubs declines to enter into debates regarding the morality of their corporate decision making, Forbes (Citation2007) has observed that, ‘the realization that … Unilever could be seen as an accomplice – albeit an unwitting one – in the Nazi dictatorship’s criminal activities, seems to have come late to the directors’ (p. 165). Like business leaders of German companies, in pursuing the concern’s interests, the Unilever executives ‘did not allow themselves to see that all commercial decisions in the Third Reich had political consequences of some kind’ (Forbes, Citation2007, p. 167). If, in this way, by continuing to do ‘business as usual’ with Nazi Germany, the company did become knowingly complicit in the international crimes that were committed under the Nazi regime, it could still be considered ‘in some measure responsible for the failure to sound the alarm over the unique dangers inherent in the ideological claims of National Socialism’ (Forbes, Citation2007, p. 167).

In the following case study, the corporate responsibility will be assessed in the case of the multinational corporation Akzo and its affiliate company Petroquímica Sudamericana that became involved in crimes against humanity committed during the military dictatorship in Argentina 1976–1983. It will be shown that members of the general board of the multinational appear to have been fully aware of the involvement of their local affiliate in these crimes and, therefore, it will be concluded that the multinational corporation itself can be viewed as having been ‘silently complicit’ in these crimes.

The Argentinian case

Argentina has a long history of political violence and military dictatorships (Larraquy, Citation2017). Of the military regimes in the twentieth century: 1930–1932, 1943–1946, 1955–1958, 1962–1963, and 1966–1973, the ultimate dictatorship, which lasted from 24 March 1976 to 9 December 1983, has been by far the most brutal in terms of the severity of the repression and the numbers of civilians killed and/or disappeared.

The years preceding the military coup in 1976 were characterised by economic and political instability. Under the previous dictatorship of Juan C. Onganía (1966–1973), the economy virtually collapsed and left-wing guerrilla movements, like the Peronist Movement Montonero and the People’s Revolutionary Party (ERP), carried out attacks to destabilise the country and demand the return of the exiled former president General Juan Perón. Targets of these attacks were not only military, police, and politicians, but also businessmen. In September 1972, for example, the Dutch general manager of Philips Argentina was taken hostage by members of the ERP.5 And, following an attack on 23 May 1973, an executive of the FORD Motor Company, died of his injuries.6

Under pressure, the military government allowed Perón to return to Argentina after having lived nearly 20 years in exile in Spain. The return of Perón would not, as was hoped, put an end to political violence, however. On the contrary, violence continued. As soon as Perón landed at the Ezeiza International Airport – on 20 June 1973 – fights broke out between left-wing Montoneros and the right-wing Peronists. The ‘massacre of Ezeiza’ left 13 dead and many more injured. On 23 September 1973 Péron was re-elected but his presidency would turn out to be a debacle from the start. Political violence escalated and already on the day following the election his fellow politician and union leader José Ignacio Rucci was murdered, allegedly by Montoneros. As the attacks of the guerrilla intensified, the right-wing paramilitary Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (Triple A) continued to kill not only guerrillas, but also left-wing activists, labour unionists and militant workers in order to ‘cleanse’ the country of these ‘subversive elements’. In the end, an estimated 1500 civilians were killed by the Triple A.

On 1 July 1974 Perón died suddenly. The inauguration of Isabel, his third wife, as his successor in the presidency served only to increase the political instability and violent attacks on businessmen, politicians, military, and police until, in 1975, the violence had reached the level that ‘just about every day a person whose name was widely known got gunned down in the street or was found, bullet-ridden, lying dead in a ditch’ (Buenos Aires Herald 27 March 2016). Altogether the guerrilla violence took the lives of 1094 victims. (Mafroni & Villaruel, Citation2014) About 70% were military or police and 30% were civilians: businessmen, labour unionists, politicians, civil servants, diplomats, judges, or ‘innocent’ victims – women and children or accidental bystanders of the attack. (Gambini, Citation2008, p. 198–208)

On 24 March 1976 the commanders of the Army, Navy, and Air Force carried out a coup d’état. The coup, when it finally came, was welcomed by a population traumatised by ongoing terrorist violence. (Carassai, Citation2013) The military junta justified their intervention by a lack of faith in the government which seemed unable to solve the political and economic crisis and the problems of escalating violence, rising inflation, and increasing unemployment. What they feared most, however, was that the rapidly deteriorating economic conditions would become fertile soil for revolutionary actions and ideas (Robben, Citation2005, p. 175).

The security doctrine of the military junta was based on their fear that left-wing political movements would take over the country and turn Argentina into a communist state. In order to prevent this, state terror was carried out in a ‘Dirty War’ against civilians suspected of (supporting) political opposition and, especially, against militant workers. Many members of trade unions and/or workers’ councils were detained, tortured, killed and/or disappeared. In addition, the military carried out a policy of de-industrialisation, as part of a systematic plan to paralyse the labour movement and shift the economy away from the manufacturing industry and towards the financial and agricultural sector.7 Companies of strategic interest and multinationals like Esso, Shell, Siemen,s and Standard Electric were placed under military command.

In the following years, thousands of civilians were abducted and illegally detained in clandestine detention centres in police stations and on military bases where they were interrogated and often tortured (Robben, Citation2005). Some of them survived but thousands were killed and/or disappeared. One third of the victims were workers suspected of having been politically active as members of trade unions and/or workers’ councils. These abductions and enforced disappearances were committed as part of a policy of ‘annihilation of subversion in industrial centers’ (Cooney, Citation2007, p. 11–14).

After a military defeat in 1982, in a failed attempt to seize the Falklands/Malvinas Islands from the United Kingdom, the junta was forced to restore democratic relations. On 30 October 1983, the Argentinians elected Raul Alfonsín as President. After assuming the presidency on 10 December 1983, Alfonsín installed a National Commission on Disappeared Persons (CONADEP) to investigate the fate of the victims of forced disappearance and other human rights violations committed during the military dictatorship. On 20 September 1984 the commission presented its report Nunca Más (Never Again) (CONADEP, Citation1986). The report documented the forced disappearance between 24 March 1976 and 9 December of 8,961 persons, but added that the actual number of disappearances was probably much higher (p. 368).8 Current estimations are that between 15 and 30 thousand civilians were killed and/or disappeared, but both figures remain contested. Moreover, there is a controversy over the qualification of the crimes committed under the military dictatorship. As these crimes were committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack against a civilian population, they qualify as crimes against humanity (DeGuzman, Citation2010, p. 125). Others, however, claim that these crimes should be considered as genocide. (Feierstein, Citation2014).

The National Commission on Disappeared Persons (CONADEP) reported that business companies were involved in the state terror against the civilian population (CONADEP, Citation1986, p. 368–378). However, as a result of an interrupted process of criminal justice (Lessa, Citation2013),9 only recently, that attention has been paid in Argentina to the role of economic accomplices in the civic-military dictatorship, either the role of foreign financial institutions that were complicit in supporting a regime well known to have been committing mass human rights violations (Bohoslavsky and Opgenhaffen, Citation2010) or the responsibility of companies ‘that supplied goods and/or services to the dictatorship or obtained benefits from it while they provided political support in return’ (Verbitzky & Bohoslavsky, Citation2016, p. 1).

Recent historical research has shown that – at least in 25 cases – business leaders and corporate executives played a role in the abduction, detention, killing, and/or forcible disappearance of workers. They rendered their companies complicit in crimes against humanity by allowing intelligence agents to infiltrate their workforce, giving military and police access to their companies to arrest workers at their workplace, or passing on information enabling the security forces to arrest workers in their homes (Basualdo et al., Citation2015).

Akzo and Petroquímica Sudamericana

In order to expand the operations of its fibre division, the Dutch multinational AKZO obtained a 20% minority share in Petroquímica Sudamericana, located in the Olmos district of La Plata, the capital of the province of Buenos Aires. This acquisition was made in the context of a complex and never-ending process of mergers, investments, divestitures, and reorganisations. At the time, in 1967, Akzo was a combination of two Dutch companies: the producer of industrial fibres Algemene Kunstzijde Unie (AKU) and the combination Koninklijke Zout Organon (KZO) producers of chemicals and pharmaceuticals. In what follows, I will be focusing on the industrial fibres division.

Corporate structure

AKU had been a joined venture, since 1929, of two fibre producers: the Dutch N.V. Nederlandsche Kunstzijdefabriek (Enka) and the German Vereinigte Glanzstoff Fabriken (VGF). In 1969, the two merged into Enka Glanzstoff – with companies in European countries like Austria, Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Italy, and The Netherlands – and Enka International – with companies outside Europe in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, India, Mexico, Nigeria, and Spain. In Argentina, Enka International took the option of increasing its 20% participation in Petroquímica Sudamericana to 40%.

Over time, Enka International became Akzo International (1972–1977) and Petroquímica Sudamericana changed its name into Hilanderías Olmos (1974–1979). In 1977, Enka Glanzstoff was renamed Enka and Akzo International became Enka International again. In 1979, Hilanderías Olmos was renamed Petroquímica Sudamericana. In 1983, Akzo sold its Enka participation in Petroquímica Sudamericana to a local Argentinian investor. In 1988, Enka Fibers became Akzo Fibers. In 1994, Akzo merged with Nobel Industries into AkzoNobel. In 1998, the industrial fibres business unit became an independent legal entity within Akzo Nobel which, in 1999, became Acordis Industrial Fibers. In 2002, the industrial fibres business unit left Acordis Industrial Fibers and became an independent business, operating under the name CORDENKA GmbH, with headquarters in Obernburg (Germany).

Management structure

In 1971, in the first full year of Akzo as a corporate group, steps were taken to create a general board of management. On 12 May 1971, at a general meeting of shareholders, a president and senior deputy president took up their positions. The board, which was in charge of the overall policy of the group, included representatives of the divisions: chemical fibres, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and consumer products.

In 1972, Enka International was reorganised into Akzo International. To further the internationalisation of the Akzo Group, Akzo International was separated from the Enka organisation. As a separate division with its own board of management, it would be reporting directly to the general board of management of the Akzo Group and, more specifically, to Mr. Hans-Joachim Schlange-Schöningen (19161991), the coordinator for the operations of the fibre division.

In 1972, Mr. Schlange-Schöningen, who had been a board member of Enka Glanzstoff, became a member and later one of the vice-presidents of the general board of management of the Akzo Group. He was also a member of the executive committee charged with the general policy and the overall course of the group. Among the members of the executive committee there existed a division of responsibilities which was based both on product-related interests and geographical policy aspects. Vice-president Schlange-Schöningen became responsible for international operations or, as it was called, ‘economic relations with state trading nations’ (Akzo Annual Report, 1976, p. 28). This included the coordination of activities in individual countries (Akzo Annual Report, 1970, p. 10). In 1977, after a massive reorganisation, Akzo International became Enka International and part of the Enka fibre division again.10

In the 1970s, Akzo had a decentralised corporate structure, whereby the executive powers over foreign affiliates were not in the hands of the board of management but exercised by the board of the division to which these affiliates belonged (Kroeze & Keulen, Citation2013, p. 1272). This was especially the case with the fibre division to which Petroquímica Sudamericana belonged (Wolpert, Citation2002, p. 61). The management structure of Akzo in the 1970s seems to fit the model (Mintzberg, Citation1984) of a multinational business corporation as a conglomerate of several semi-autonomous divisions that are united under one overarching structure and a general board. This is the type of organisation in which information about what happens on the shop floor is expected to never reach the level of the general board (Mintzberg, 1984, p. 81; Hornman, Citation2016, p. 240). In order to question this assumption of corporate ignorance, I will document what members of the board of management of Akzo actually knew was happening in Argentina and, more specifically, at Petroquímica Sudamericana’s production plant Hilanderías Olmos.

Context of operation

In the 1970s in Argentina, Akzo was operating in a context of socio-economic disorganisation and extreme political instability. The socio-economic context was one of intense labour conflicts and escalating violence. Traditionally, the unions in Argentina had been extremely powerful and workers were already more than willing to protest and go on strike when, for example, a labour conflict over a wage-freeze in spite of an extension of the working day, could not be resolved by negotiation. If companies responded to strikes with disciplinary measures like lock-outs, pay cuts, or dismissals, this would only ignite new protests and demonstrations.

Petroquímica Sudamericana’s production plant Hilanderías Olmos, with a workforce of about 1500, was a site of exceptionally intense labour conflicts. Inside the company several militant political groups were active. Some of them, like Avanzada Petroquímica (which belonged to the Socialist Labor Party) or Trinchera Textil (which belonged to Política Obrera or Workers Party), operated openly. Others, like the Comisión Resistencia Combativa (which belonged to the Communist Marxist-Leninist Party) operated in a (semi-) clandestine way (Bretal, Citation2008, p. 51).

In 1971, after organising a general strike for a pay rise and better working conditions, members of the company’s official workers council were fired (Longo, Citation2008). One of them, Juan Carlos Leiva, would later – on 14 October 1974 – be assassinated by the Argentinian Anticommunist Alliance (AAA). The so-called Triple A was a secret paramilitary organisation, closely related to the Buenos Aires Provincial Police, which assassinated union leaders and civil rights activists. In revenge for the murder of Leiva, the technical director of Hilanderías Olmos, Emilio Hasalik (34), was assassinated by a commando of the People’s Revolutionary Army (ERP) on 20 December 1974 (Alonso, Citation2015, p. 95).

After a site-visit at Hilanderías Olmos, from 26 January to 1 February 1975, two representatives – the director of internal auditing at Akzo and a financial officer of Akzo International – reported to the general board of management that the murder had nothing to do with the foreign shareholder. They had the ‘impression’ that, initially, the ERP intended to assassinate Mr. Jorge Curi (1908–1998), the owner and president of the PSSA Group and/or the general manager of Hilanderías Olmos, Mr. Pegorari. It was to be a pay-back for their unwavering position during the wage negotiations in the fall of 1974.11 The Akzo representatives also reported that, following the murder of Mr. Hasalik, Mr. Pegorari had disappeared, while other staff members had quit their job or were no longer coming to work. The Akzo representatives feared a vacuum in the executive of the company, because the principal owner, Mr. Jorge Curi, also stayed home and urged his son to stay where he was, in Switzerland.12 In a meeting on 8 January 1975, the workers’ representatives no longer recognised Mr. Curi’s authority, which compelled him to consider selling his share in the PSSA Group, unless the political climate in Argentina rapidly improved.13

Mr. Curi had reported death threats against corporate executives with explosives detonating at their residences and inside the factory and had asked for government protection (Alonso, Citation2015, p. 95). In a press release of 26 November 1975,14 Akzo noted that, after a period of relative peace, a new conflict situation occurred as a result of which production halted. This caused the Argentine partner to turn to the government. The government intervened by ordering mandatory arbitration.15 This resulted in the appointment of the Deputy Secretary General of the Labor Union in the Textile Industry, Asociación Obrera Textil (AOT), Delfor Giménez, as director of Hilanderías Olmos.16

On 1 December 1975, a board member and financial officer of Akzo International and the financial director of the Akzo Group, met with Dr. Villanueva, the leader of a delegation of the Argentinian government visiting The Netherlands. According to the minutes of the meeting, Dr. Villanueva had told them that the government intervention in Hilanderías Olmos had to be carried out because ‘a complete cell of the People’s Revolutionary Army (ERP) was present in Olmos’.17 Dr. Villanueva observed that normally the countervailing power of the labour unions would be sufficient to prevent such a situation, but in Olmos this had not been the case. He did not consider Deputy Secretary General Giménez to be a strong enough leader to solve the problem of getting the factory up and running again. After contacting ‘Buenos Aires’, he reported that a decision was imminent to retire Giménez as a director and return the company to its legitimate owners.18

On 15 December 1975 vice-president Schlange-Schöningen was informed that the situation at Olmos was ‘unique in Argentina’.19 The following day, the vice-president accompanied by the financial director of the Akzo Group went to Argentina ‘to obtain a first-hand impression of the underlying causes and latest developments of the Government intervention’.20 Upon their arrival, they soon discovered that, indeed, ‘a number of extremists had gained such a strong position in the plant that the leaders of the labor union lost control and were no longer able to maintain orderly working conditions.’21 In discussions with the Dutch ambassador, local advisers, and representatives of Akzo, they ‘tried to establish the underlying reasons for the present difficult situation.’22 According to the ambassador, the principal owner, ‘Mr. Curi, as a result of his historically tough position in wage negotiations, has created considerable labor antagonism which may have aggravated the conflict.’23

In a meeting on 17 December 1975 the Under-Secretaries of Economic Affairs and Commerce defended the government intervention as ‘the most effective method of getting rid of the extremists.’24 They claimed that, after several months of intense labour conflict involving sabotage, boycott, strike, and occupation, ‘the plant was again partly operating, as over 800 people had showed up for work’. When the vice-president of the Akzo Group disclaimed this, he was invited to inspect the plant the next day together with the financial director of the Akzo Group. After visiting the site, it was noted that ‘the plant was generally in a bad condition’ and that ‘there appeared to be no clear concept of how to weed out the extreme elements in the plant.’25 Taking into account that, according to Mr. Curi, ‘there is a considerable chance that in the beginning of 1976 the military will assume a more important role in government and force a tougher stand against extremists’, it was proposed to the general boards of Akzo and Akzo International that it would be best to ‘await … the outcome of the present political turmoil’.26

In a personal letter of 15 March 1976 to vice-president Schlange-Schöningen, the Dutch ambassador reported that the situation ‘is – if possible – worsening every day’ and ‘furthermore, politically speaking, rumors have it that this government is in its last agony’ and ‘a military take-over is imminent.’27 When nine days later, on 24 March 1976, the military committed a coup d’état, this could not have come as a great surprise to the vice-president of Akzo.

Military control

The aim of the military junta was to restructure the Argentinian economy which, in their view, required that pockets of resistance within the working classes be eradicated. A law prohibited all union activity, like assemblies, reunions, congresses, and elections, while enabling the military government to intervene by appointing military personnel in the direction of companies and replacing union representatives in the workers council. At Hilanderías Olmos, director ad interim Delfor Giménez was arrested and charged with ‘grave irregularities in the administration of the company’s assets’.28 He was replaced by retired Coronel Carlos Luzuriaga. Akzo representatives showed their willingness to cooperate with the military by sending, at the request of Coronel Luzuriaga, a team of experts to evaluate the general and technical situation of the plant.29 On the basis of their findings, Akzo was not willing to take the company back in its current state. When the government intervention officially ended, on 25 October 1976, Coronel Luzuriaga was replaced by court order with retired Brigade General Manuel A. Laprida. Incidentally, that same day managing director Roberto Moyano (45) of Hilanderías Olmos was murdered by members of the Montoneros guerrilla group. General Laprida would be equipped with a staff of lawyers, technical managers, and accountants to be appointed by the Judiciary, the Secretary of Commerce, and the company Hilanderías Olmos itself. In a telephone conversation on 17 November 1976, the regional director reported to the president of Akzo International that he had ‘an exceptionally positive impression’ of Mr. Laprida and very much appreciated the general’s ‘outstanding contacts’.30 Yet, he considered the permanent stationing of an Akzo representative as general manager at Olmos ‘still too dangerous’.31

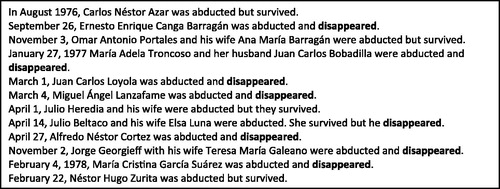

There is evidence that, between August 1976 and April 1977, within the relatively short time period of nine months, at least 18 persons were abducted by military and security forces and illegally detained (Alonso, Citation2015 p. 99–101).32 See . Seven victims (four men and three women) survived their detention; 11 victims (eight men and three women) had disappeared. Seven victims (six men and one woman) were working at the company at the time of their abduction. Six had been fired or left work ‘voluntarily’ for fear of being arrested. They may be counted as victims related to the company because their names have been found on lists that were drawn up by agents of the Buenos Aires Provincial Police after having infiltrated the workforce in Olmos between 1970 and 1978 (Alonso, Citation2015, p. 101). Three workers were abducted with their wife and one female worker was arrested with her husband. Most of the abductions were executed in a concerted fashion and took place at the workplace of the victims or their home with assistance of or in cooperation with the company. Home addresses of workers and ex-workers were known to the company and made available to the security forces. An example is the case of student-worker Alfredo Néstor Cortez who, two weeks after his house had been searched by Federal Police, left home to go to work and disappeared. Some workers have testified that they were fortunate to escape abduction because security forces went looking for them at an address where they no longer lived but which the company still had on file and must have passed on to the security forces (Alonso, Citation2015).

There is evidence that some of the abductions took place with the cooperation of company staff. In the case of Miguel Angel Lanzafame, for example, a co-worker has testified in court that Lanzafame was taken away in a car after he had been called to the front desk by the head of security of the company, Andrés Avelino Pinelli on the pretext that his grandmother was ill. In the case of Juan Carlos Loyola, his mother has testified to the National Commission on Disappeared Persons (CONADEP) that Pinelli was present when her son was abducted at their home address (Alonso, Citation2015, p. 105–106).

There is evidence that Hilanderías Olmos not only assisted, but also invited and welcomed the military and security forces. In 1977, the principle owner Mr. Curi published a book in which he vowed his loyalty to the military regime guaranteeing the authorities the full collaboration of his company (Curi, Citation1977, p. 234).

Intelligence reports were found in the Provincial Memory Archive in La Plata showing that Mr. Jorge Curi hired three undercover agents of the Dirección de Inteligencia de la Policía de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (DIPPBA) to infiltrate and identify members of a ‘left-wing cell’ that ‘incited conflicts and strikes for higher wages.’33 Black lists of ‘trouble makers’ have been found in the archive that were used to identify the ‘most wanted’ workers and ex-workers of Hilanderías Olmos (Alonso, Citation2015, p. 105).

On 30 May 1978, just before the military intervention formally ended, general Laprida wrote (in Spanish) to the personnel of Hilanderías Olmos: ‘I believe to have kept all my promises and, in particular, the most important one: to create the peaceful conditions needed to hand the company over to its legitimate owners in the most favorable conditions for everybody.’34

Awareness

According to the assumption of corporate ignorance, the board of management of Akzo would normally not have been informed about what happened at an affiliate like Hilanderías Olmos which belonged to one of several divisions of the multinational corporation. However, this is not what I have found. In this case, at least one member of the general board of management of Akzo, i.e. vice-president Schlange-Schöningen, did take an interest in how their affiliate fared under the military dictatorship in Argentina and, therefore, ensured that it was kept closely informed about developments in Argentina and at Hilanderías Olmos.35

In refutation of the assumption that the more remote the action is, the less likely the general board is to know about it, the documents show that, the vice-president knew what was happening on the ground at their affiliate Hilanderías Olmos. As the international coordinator of the activities in individual countries and (former) president of Akzo International (1974–1975), he was informed by government officials while local representatives of Akzo provided him with a constant stream of information from translated newspaper clippings, reports, letters, cables, and telephone calls.37 In December 1975, he made a site-visit to Argentina to obtain a first-hand impression of the situation. He talked to local representatives of Akzo and Petroquímica Sudamericana and had discussions with Argentinian government officials about possible solutions for Hilanderías Olmos.

On 5 April 1976, less than two weeks after the military take-over of 24 March, vice-president Schlange-Schöningen was informed that ‘this week a military official is going to be appointed in order to replace the former controller. The general opinion is that – as soon as possible – the plant and the offices will be returned to us.’37 On 12 April 1976, discussions with the authorities are expected to result in an agreement in two weeks and returning the plant in four weeks. ‘In addition, replacement of the current interventor by a military ‘interventor’ is expected any time soon.’38

On 20 July 1976, vice-president Schlange-Schöningen met with Secretary of Economic Affairs José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz (1925–2013) to discuss the situation. After the meeting, the vice-president reported that ‘the wait is for concrete proposals by the government to solve the problems related to Olmos.’ 39

After the removal and replacement of Deputy Secretary General Giménez as director, first by coronel Luzuriaga and then by retired brigade general Laprida, at least four Akzo representatives met the general in person. After a site-visit in December 1977, the director for Economic Relations with State Trading Nations, reported to – amongst others – the vice-president of Akzo that: ‘In Olmos only general Laprida is present as court appointed administrator/governor.’40 And, on 27 March 1978, a representative of Akzo reported to the financial officer of Akzo International that he ‘with the good help of General Laprida and his staff established an office in Hilanderías Olmos.’41

Although the company archive did not reveal any documents reporting the abduction of workers, as has been shown above, the presence of so-called ‘extremists’ in the plant was a cause for concern of the members of the select committee of the general board of management who, in the summer and fall of 1976, were constantly briefed on the situation at Hilanderías Olmos. It must, therefore, have been good news to them that, after the military take-over, the affiliate came under military command. Especially, when the command was taken over by a retired brigade general who stated publicly that it was his job ‘to eradicate the syndicalist militancy inside the factory and give the company back to its owners’ (Alonso, Citation2015, p. 98).

On 29 April 1976, one month after the military take-over, the general board of management of the Akzo Group concluded that, ‘Given the developments at Olmos in Argentina and the position of Mr. Curi, Akzo must get more grip on the case’.42 Excerpts from the minutes show that in the summer and the fall of 1976 the select committee43 of the general board of management was constantly being briefed on the situation at the Argentinian affiliate. When, in December 1977, the financial director of the Akzo Group visited Hilanderías Olmos again and reported to Schlange-Schöningen that ‘morale of management and personnel seems … to have improved significantly’,44 the vice-president could and, probably should, have concluded that, somehow, the military had managed to offer them protection and ‘weed out the extreme elements in the plant.’

It seems unlikely that the vice-president, who was so well informed, knew nothing about the crimes against humanity that were committed in Argentina during the military dictatorship. Amnesty International, and also the Council of Churches and the International Labor Organization (ILO) drew attention to the systematic human rights violations and enforced disappearances in Argentina.45 In January 1978, a boycott action was launched which resulted in 60,000 signatures in favour of a petition against the participation of the Dutch national team in the FIFA World Cup tournament to be held in Argentina later that year. Only a few members of Parliament supported the idea that a trade boycott should be imposed on Argentina. In spite of parliamentary questions concerning the abductions and disappearances in Argentina, the Dutch government did not take an official stand until 1981.46

In the meantime, the Dutch government followed a policy of understanding. Given the unstable political and economic situation in 1976, the military takeover was taken for granted. It was believed or at least hoped that democracy would soon be restored. The government thus permitted Dutch companies to export goods and services, even military equipment, to Argentina and stimulated trade relations by providing credit guarantees. In addition, it facilitated at least 36 companies, including Akzo, to continue operating their subsidiaries in Argentina. As a result, export to Argentina tripled between 1977 and 1981, making The Netherlands Argentina’s third largest trade partner after the United States and Brazil. Clearly, in the foreign policy of The Netherlands during the military dictatorship in Argentina economic interests were given priority over human rights (Grünfeld, Citation2002).47 It could, therefore, be argued that Akzo merely followed the foreign and economic policies of the government.

The Dutch ambassador in Argentina, Mr. van den Brandeler, arranged several meetings –both in Argentina and The Netherlands – between Akzo representatives and officials of the Military Government. 48 In fact, the ambassador was personally involved in finding a mutually acceptable solution for Hilanderías Olmos.49 For the military government a ‘real solution’ would only be feasible if Akzo would take over full management responsibility. In a letter to vice-president Schlange-Schöningen, the financial director of the Akzo Group reported on the ‘discussions with the Secretaries of Economics and Industry, Dr. Padilla and Dr. Podestá about the conditions for Akzo to take over management responsibility for Hilanderías Olmos’ and noted that the director of the Akzo Group for Economic Relations with State Trading Nations, had offered ‘our preparedness to assume responsibility, if a fair solution can be reached as to damage payments.’50 The director noted that the continuity of Hilanderías Olmos depended on the compensation the government is willing to pay for damages, i.e. loss of income caused by the government intervention.51 Initially, Akzo claimed that 85 million US$ would be needed to prevent Hilanderías Olmos from closing or even bankruptcy.52 Ultimately, after lengthy negotiations, a settlement was reached in 1979 according to which 10 million US$ was paid to the Akzo holding Fontanus Argentina. After the deal was closed, it was noted that ‘our companies in the Buenos Aires area have, once again, shown a powerful and very satisfactory profit development.’53

An indication that the board of management might have had concerns that their business in Argentina could raise questions, is that, in its Annual Report 1979, for the very first time – and, for the time being, also the last time – Akzo included a statement on human rights.

The presence of Akzo companies in many parts of the world regularly gives occasion to questions about …infringements of fundamental human rights, particularly in countries with controversial regimes. Although the political and public debate of these very complex issues is far from completed, we undeniably have a certain responsibility here. This responsibility, and such means as we have to exert influence in this regard, relate primarily to situations affecting our own employees. Where we participate in a business, our room for maneuver and our freedom to take a position may be restricted by the partnership. We furthermore feel that a distinction should be made between situations where a company is already established in a country and situations where it is considering beginning operations. While we do not believe it our duty as a company to explicitly declare ourselves for or against any political system, or for or against a particular government, we expect our managers to implement policies which fully respect human dignity and equality, even in countries where the fundamental rights and freedoms laid down in the United Nations are not sufficiently guaranteed. (Akzo Annual Report, 1979, p. 16)

In this statement, the board of management admitted that the ‘presence of Akzo companies in many parts of the world regularly gives occasion to questions about infringements of fundamental human rights’ (Akzo Annual Report, 1979, p. 16). In this statement, the board of management of Akzo subscribed to ‘a certain responsibility’ for infringements of fundamental human rights in countries with controversial regimes, albeit with the restriction that this ‘responsibility, and such means as we have to exert influence in this regard, relate primarily to situations affecting our own employees’ (Ibid.).

This claim of due diligence was ex-post facto. There is no evidence to show or even suggest that either vice-president Schlange-Schöningen or local Akzo representatives did anything to restrain the principal owner from collaborating with the military. And, in spite of the claim, made in 1979, that ‘we expect our managers to implement policies which fully respect human dignity and equality, even in countries where the fundamental rights and freedoms … are not sufficiently guaranteed’ (Akzo Annual Report, 1979, p. 16), local representatives of Akzo were not instructed to try to prevent the abduction of workers in and around Hilanderías Olmos. On the contrary, Akzo asked their representatives to fully cooperate with the military governance of Hilanderías Olmos, while, at the same time, negotiating with the military regime and offering to assume full management responsibility for its affiliate. Formally, Akzo may just have been a minority shareholder in Petroquímica Sudamericana. However, by deciding to offer the military government their willingness to take full management responsibility for Hilanderías Olmos, the general board of management knowingly exposed the Akzo corporation to the risk of becoming implicated in the abduction of workers in and around the affiliate.

An empirically grounded account

This case study suggests that the assumption of corporate ignorance does not have general validity. It might be true that the board of a multinational corporation often simply ‘lacks the time and knowledge to micromanage the divisions’ (Hornman, Citation2016, p. 501). In this respect, the general board of management of the Akzo Group was no exception. It was their business to set the course of the Group as a whole and to direct its operations which, in principle, did not entail direct operational or functional tasks and responsibilities (Akzo Annual Report, 1977, p. 32). However, it is problematic to simply assume that, given the usual structure and functioning of a multinational corporation, the members of a general board of management will not be aware of any misconduct in a production unit in a distant country. Instead a careful empirical – and, in this case, historical – reconstruction of the management structure and the lines of command and communication of the multinational are required.

On the basis of this case study, the assumption of ‘corporate ignorance’ should be refuted.54 In exceptional situations, when the interests of a multinational corporation are at stake, the general board of management will pay attention to what, normally speaking, would not be their concern and, therefore, make sure that they know what they need to know.

In this particular case, it was unusual in the first place that in 1972 the international coordination was transferred from the fibre division to Akzo International. This organisation had its own board of management and reported directly to a member of the general board of management of the Akzo Group responsible for international operations. As a result of this reorganisation, it became much less likely that information about misconduct on the shop floor of an affiliate in a distant country would remain at the management level of the division and fail to come to the attention of the general board.

In the second place, the unique situation at Petroquímica Sudamericana’s production plant Hilanderías Olmos, which caused the Argentinian government to intervene, was reason for the vice-president of the Akzo Group to follow closely what was happening in Argentina and, especially, at their local affiliate. On the basis of available documents, it cannot be maintained that the general board of management was ‘insufficiently informed to be able to make an adequate assessment of the nature, severity, and scope of the situation at hand’ (Hornman, Citation2016, p. 505).

However, even before the military takeover in 1976, the situation was exceptional because the business community in Argentina was being targeted by left-wing urban guerrilla groups. Hundreds of corporate executives were taken hostage, some were released for a ransom but 54 of them were killed, including the technical director of Hilanderías Olmos in 1974.55 Like many European and American companies, Akzo decided to temporally withdraw its corporate executives for reasons of security.56 Other (multinational) companies took extra security measures and/or sought state-protection.57 Given that even before the military take-over there was already ample cause to be concerned, it is not surprising that attention would continue to be paid to what was happening in Argentina, especially, at the local affiliate Hilanderías Olmos.

It is unlikely that the entire general board of management – which was being advised by a former Dutch Secretary of Foreign Affairs – would have been completely ignorant of the brutal repression and violation of human rights under the military dictatorship (Baud, Citation2001). The vice-president, who was responsible for the international operations of the Akzo Group, was kept closely informed by the regional director and other Akzo representatives visiting the affiliate about what was going on in Argentina and, more specifically, at Hilanderías Olmos: e.g. that, after the military take-over in 1976, industrial companies came under military command, all union activity was prohibited, military and police flooded the streets, workers and civilians were being abducted and ‘disappeared’ (Baud, Citation2001, p. 184). When Hilanderías Olmos was placed under military command and the director ad interim, like so many other labour union leaders in Argentina, was arrested, there was every reason for concern or even for raising questions about what would happen to the so-called ‘extremists’, the militant workers, and the members of the workers’ council of the affiliate. Instead, it was reported that: ‘In Argentina a return to more normal conditions seems under way.’58

When Hilanderías Olmos was placed under military command, the vice-president could have been aware that Hilanderías Olmos might expose Akzo to the risk of corporate complicity in the crimes against humanity to which Amnesty International, the Council of Churches, and the International Labor Organization (ILO) were drawing attention. The vice-president had been informed that ‘extremists’ were operating inside Hilanderías Olmos and had taken the advice of the owner to wait for the military to force a tougher stand against these militant workers. When, nine months later, an Akzo representative reported a ‘significant improvement’ in morale of management and personnel, the vice-president could have concluded that the military found a way to solve what was considered the problem of ‘extremists’ in the plant. In other words, rather than being ignorant, the vice-president knew but ignored what was happening in and around the affiliate.

With the caveat that historical documentation on this case is incomplete,59 as yet nothing has been found suggesting that local representatives of Akzo were instructed to prevent the abduction of workers in and around Hilanderías Olmos. On the contrary, like the principal owner, who vowed his loyalty to the military regime and guaranteed the authorities full collaboration with their policies, Akzo instructed its representatives to fully cooperate with the military governance of Petroquímica Sudamericana. It is hard to believe that these local Akzo representatives did not know about the abductions and disappearances of civilians, including personnel of their affiliate for which later – in the Annual Report 1979 – the board of management admitted to have a ‘certain responsibility’.

Obviously, today we think differently about corporate responsibility than in the 1970s when international organisations like the United Nations were beginning to recognise corporate responsibility for adverse effects of business activities on human rights and the duty to protect (Zerk, Citation2006). In order to understand why the general board of management of Akzo continued to do business with the military government, it has to be taken into account that Akzo’s corporate policy complied with the foreign policy of the Dutch government which was actively promoting trade relations with Argentina and urging diplomats to intensify their contacts with the Argentinian authorities.60 Multilaterally, in the International Commission of Jurists and the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, Dutch representatives became critical of Argentina, but the bilateral relations between The Netherlands and Argentina remained unchanged. (Grünfeld, Citation2002)

We have seen that by continuing to do business and cooperating with the military while knowing what was going on in Argentina and, more specifically, in and around their affiliate Petroquímica Sudamericana, representatives of the Akzo Group remained in close contact to both the authorities and the perpetrators responsible for actual crimes against humanity as well as near the situation in which these crimes were being committed.

With the benefit of hindsight, it could be argued that Akzo became silently complicit (Clapham, Citation2001) in the crimes against humanity that were committed in Argentina and, more specifically, in and around their affiliate Hilanderías Olmos. According to current standards, a company may be considered silently complicit if its board of management, ‘is aware that human rights violations are occurring, but does not intervene with the authorities to try and prevent or stop the violations’ (International Council on Human Rights Policy, Citation2002, p. 133). Silent complicity is considered by the United Nations as the most controversial type of complicity.61 It is a rather indirect form of complicity for which legal liability is unlikely (United Nations, Citation2008a, p. 21). Seriously considering it is, however, relevant from a moral point of view (United Nations, Citation2008b, p. 17; Wettstein, Citation2012, p. 42–43). In business ethics, silent complicity has been defined as ‘the failure by a company to raise the question of systematic or continuous human rights violations in its interactions with the appropriate authorities’ (Wettstein, Citation2010, p. 37). However, a failure to raise this question ‘as such does not necessarily signify that a corporation is silently complicit’ (Wettstein, Citation2012, p. 42). Silent complicity also requires that the breaking of silence could reasonably be expected to have (had) an impact by influencing the behaviour of an actual or potential perpetrator (Wettstein, Citation2012, p. 46).

In the case of Akzo, its business representatives were, indeed, in ‘a position to exert pressure or influence for the purpose of improving the situation of the victims’ (Wettstein, Citation2012, p. 46). The vice-president of Akzo met in person and face-to-face with the Argentinian Secretary of Economic Affairs and Akzo representatives negotiated with officials of the Military Government in order to find a mutually acceptable solution for Hilanderías Olmos. In order to secure the production of industrial fibres which was of strategic importance to the Argentinian textile industry, the military government needed Akzo to cooperate and assume managerial responsibility. In hindsight, and by current standards, it could, therefore, be argued that by failing to raise questions about the crimes against humanity that were known to be committed in Argentina and, more specifically, in and around its local affiliate, the business representatives of Akzo made their multinational corporation become ‘silently complicit’ in what would later turn out to be the worst tragedy in twentieth century Argentinian history. In this way, they gave the notion of ‘corporate ignorance’ a bitter twist.

Notes on contributor

Willem de Haan (MA University of Groningen, PhD University of Utrecht) is a Professor of Criminology Em. and Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Criminal Law and Criminology at the VU University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. He is the author of The Politics of Redress. Crime, Punishment and Penal Abolition. London: Unwin Hyman, 1990. His current research is in the field genocide studies and corporate involvement in international crimes. See: ‘Knowing what we know now. International Crimes in Historical Perspective’. Journal of International Criminal Justice. 13, 4, 2015, p. 783-799; ‘Denialism and the problem of indifference’ in: Nelen, H., Willems, J. C. M. & Moerland, R. (eds.), Denialism and Human Rights. Maastricht: Intersentia, 2016, p. 9-23.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Hans Vogel and Marjan Smits for their suggestion to look at the issue of corporate involvement of Dutch multinationals in crimes against humanity in Argentina. Many thanks to Annika van Baar, Victoria Basualdo, Michiel Baud, Wim Huisman, Joost Jonker, and Ton Robben for their comments and advice. Special thanks to corporate archivist Fred van Daalen and to Lorena Balardini, Mariel Alonso, and Tomás Griffa of the Center for Legal and Social Studies (CELS) in Buenos Aires for their research assistance and to the Amsterdam Law and Behavior Institute for their financial support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

Notes

1 Research for this study was conducted in archives in Argentina and The Netherlands. In Argentina, these archives were the Archivo Nacional de la Memoria; Archivo de la Dirección Provincial de Inteligencia de la Policía de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (DIPBA) en poder de la Comisión Provincial por la Memoria (CPM); Archivo del Área de Economía y Tecnología de FLACSO-Argentina; Archivo Jorge Schvarzer de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires; Archivo del Centro de Documentación e Investigación de la Cultura de Izquierdas en Argentina (CEDINCI); Hemeroteca de la Biblioteca del Congreso de la Nación; and Hemeroteca de la Biblioteca Nacional. In the Netherlands, research was conducted in The National Archive and the Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in The Hague, as well as in The Provincial Archive and the Corporate Archive of AkzoNobel in Arnhem.

2 See: https://business-humanrights.org. In many cases, accusations of corporate complicity in international crimes arise in the context of business transactions with ‘bad actors’, often states, committing these crimes. Often corporate involvement in them consists of what would usually be regarded as ordinary and acceptable business activity (Michalowski, Citation2015, p. 405) or ‘business as usual’ (Huisman, Citation2010).

3 On 16 June 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council unanimously endorsed the Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights. See John Ruggie, United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, 21 March 2011. Human Rights, Transnational Corporations and other Business Enterprises. Note by the Secretary of the United Nations, 4 August 2016, p. 13.

4 This article concerns the former Akzo corporation and its industrial fibre division Akzo International which after a series of mergers, divestitures, and reorganisations, is no longer part of the current AkzoNobel.

5 Reformatorisch Dagblad, 7 September 1972.

6 Time Magazine, 14 January 1974.

7 As a result, the government allied itself more with the Argentinian Rural Society (Sociedad Rural Argentina, SRA) than with the Industrial Union of Argentina (Union Industrial de Argentina, UIA). (Cooney, Citation2007, p. 11–12)

8 Current estimates by human rights organisations in Argentina that at least 30,000 people forcibly disappeared, are contested (La Nacion, 3 August 2009).

9 From 1983 until today, Argentina has gone through a whole range of transitional justice measures, including truth commissions, criminal trials, amnesty laws, and sustained criminal justice after the Supreme Court ruled that the amnesty laws were unconstitutional in 2006.

10 In 1978, Mr. Schlange-Schöningen resigned as vice-president of the board of management to be appointed as member of the Supervisory Council (Akzo Annual Report, 1978).

11 Visit to Buenos Aires from 26 January to 1 February 1975. Report (in Dutch) of 4 February 1975, p. 2. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

12 Ibid., p. 3.

13 Id., p. 3–4.

14 Press Release (in Dutch) of 26 November 1975. Gelders Archief.

15 Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, 9 September 1975.

16 Resolution 173 of the Secretary of Commerce, 12 November 1975.

17 This was the guerrilla group that had claimed the murder of technical director Hasalik of Hilanderías Olmos in 1974. Minutes (in Dutch 1975, p. 2.) of 5 December 1975 of a meeting with Dr. Villanueva in Amsterdam on 1 December 1975 Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

18 Ibid., p. 3.

19 Letter (in Dutch) to H.J. Schlange-Schöningen, 15 December 1975. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

20 Memorandum of 5 January 1976 (in Dutch) to Members of the Select Committee of the Board of Management of the Akzo Group and Members of the Board of Akzo International, p. 2. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel

21 Id., p. 2.

22 Id., p. 2.

23 Id., p. 2.

24 Id., p. 4.

25 Id., p. 4.

26 Id., p. 5.

27 Letter (in English) to the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, No. 862, 15 March 1976. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

28 La Razón, 14 September 1976. Giménez was convicted for having increased salaries but released from prison on 5 January 1977. He survived and passed away in December 2015.

29 Letter (in English) from the president of Akzo International to the Embassy of the Republic of Argentina in The Hague, of 2 July 1976. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

30 Minutes (in Dutch) of telephone conversation, 17 November 1976. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

31 Ibid.

32 Names of five more victims appeared on a list of victims in the textile industries of the Curi family prepared by the Agencia de Comunicación Rodolfo Walsh. See A. Meyer, ‘Echando mano a viejos métodos’, Pagina 12, 18 February 2008. These victims have not been included because their data are incomplete. There are families of victims that never reported their missing for fear of reprisal. But even if families reported their death or disappearance, it cannot be excluded that victims were not identified as workers or that the companies they worked for were not recorded. In some testimonies victims are merely mentioned and, subsequently, recorded as ‘victima sin denuncia formal’ (victim without a formal complaint).

33 Bretal, Citation2008, p. 50, note 27.

34 Letter of Manuel A. Laprida. (Alonso, Citation2015, 103)

35 One other member of the board of management (1972–1980) must have known Petroquímica Sudamericana because he was on the photograph taken in 1967 when the contract with principal owner Jorge Curi was signed. More importantly, however, as a member of the select committee of the general board of management of Akzo he received the memorandum on the situation at Hilanderías Olmos in 1976.

36 Some of them were also members of the board of Petroquímica Sudamericana and Hilanderías Olmos. Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, 17 May 1976.

37 Cable msg 4894 of 2 April 1976 to Akzo International. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

38 Minutes of telephone call on 12 April 1976. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

39 Report of 20 July 1976 on conversation of Mr. Schlange-Schöningen with Mr. Martinez de Hoz. Excerpt from minutes of Meeting Select Committee of General Board of Management of the Akzo Group, 27 July 1976. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

40 Letter (in Dutch) to Schlange-Schöningen, 6 January 1978. Gelders Archief.

41 Letter (in Dutch) to Akzo International, 27 March 1978. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

42 Excerpt from Minutes of Meeting of General Board of Management 29 April 1976. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

43 The select committee of the general board of management of the Akzo Group included the president, vice-president Schlange-Schöningen, three board members, the director of strategic planning, the secretary, and policy advisor drs. Norbert Schmelzer, the former Secretary of Foreign Affairs (1971–1973). In 1973, he was appointed as advisor of the board of management, ‘specifically in relation to international affairs and issues of a general social nature’ (Akzo Annual Report, 1975, p. 38).

44 Letter (in English) to Mr. H.J. Schlange-Schöningen, 21 December 1977. Gelders Archief.

45 Report of an Amnesty International Mission to Argentina 6–15 November 1976. London: Amnesty International, 1 March 1977.

46 Argentinië nota. White Paper, TK 1980–1981 16588 Nr.2, 15 January 1981.

47 As a result, export to Argentina tripled between 1977 and 1981, making The Netherlands Argentina’s third largest trade partner after the United States and Brazil. (Grünfeld, Citation2002, p. 42)

48 The ambassador reported to the government that he personally knew general Videla, the leader of the military junta, as a charming, deeply religious person, not at all fitting the image of a dictator. Trouw, 4 July 1998.

49 Memorandum to Members of the General Committee of the Board of Management of the Akzo Group and Members of the Board of Akzo International, 5 January 1976. Corporate Archive AkzoNobel.

50 Letter (in English) to Mr. H.J. Schlange-Schöningen, 21 December 1977. Gelders Archief.

51 Letter (in Dutch), 26 June 1978. Gelders Archief.

52 Ibid.

53 Letter (in Dutch) to Enka Board, 31 May 1979. Gelders Archief.

54 It is beyond the scope of this article to consider what the exceptions to the general assumption of corporate ignorance would imply for existing ideas about corporate complicity in international crimes and human rights violations.

55 On 30 December 1974 general manager Roberto Abeigón and human resources manager Manuel Martínez of Miluz, another Akzo affiliate which belonged to their coating division, were killed inside the factory by a commando of the People’s Revolutionary Army (ERP). The operation was claimed as revenge for the killing of two militant student workers by the Argentinian Anticommunist Alliance (AAA), supposedly following orders of the company.

56 Press Release of 26 November 1975. Gelders Archief.

57 Ford, for example, asked for army protection. Time Magazine, 14 January 1974.

58 Akzo Annual Report, 1976, p. 20.

59 Some documents were simply missing. Others, like the minutes of the meetings of General Board of Management, were classified and, therefore, remained undisclosed.

60 Letter of July 1977 from the Ministry of Economic Affairs to the Dutch Embassy in Buenos Aires. Algemeen Dagblad, 3 March 2001.

References

- Abelshauser, W. (2002). Rüstungsschmiede der Nation? Der Kruppkonzern im Dritten Reich und in der Nachkriegszeit 1933 bis 1953. In: Lothar Gall (Ed.), Krupp im 20. Jahrhundert. Berlin Siedler Verlag, pp. 328–374.

- Akzo Annual Reports at https://www.akzonobel.com/en/for-investors/all-reports/

- Allen, M. T. (2002). The business of genocide: The SS, Slave Labour and the Concentration Camps. Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press.

- Alonso, M. (2015). Petroquímica Sudamericana. In V. Basualdo et. al., Responsabilidad empresarial en delitos de lesa humanidad. Represión a trabajadores durante el terrorismo de Estado. Buenos Aires: Editorial Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos de la Nación pp. 87–102.

- Amatori, F. & Jones, G. (2003). Business History around the World at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Basualdo, V. et. al. (2015). Responsabilidad empresarial en delitos de lesa humanidad. Represión a trabajadores durante el terrorismo de Estado. Buenos Aires: Editorial Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos de la Nación.

- Baud, M. (2001). Military violence, civil responsibility. Argentinian and Dutch perspectives at the military regime in Argentina (1976–1983). The Hague: SDU Uitgevers.

- Berghahn, V.R. (2004). ‘Writing the history of business in the Third Reich’, in J. Huener and F.R. Nicosia (eds) Business and Industry in Nazi Germany, New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 129–148.

- Berghoff, H., “Business History”, in: Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes (Hrsg.), International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Band 2, Oxford 2001, pp. 1421–1426.

- Berghoff, H., ‘Business History’, in: James D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Amsterdam: Elsevier 2015, pp. 21–26.

- Berghoff, H., Kocka, J. & Ziegler, D. (eds.) (2013). Introduction. In: Business in the Age of Extremes in Central Europe: Essays in Modern German and Austrian Economic History. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Billstein, R., Fings, K., Kugler, A., & Nicholas, L. (2004). Working for the Enemy. Ford, General Motors and Forced Labor in Germany during the Second World War. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Black, E. (2012). IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation. New York: Dialog Press.

- Bohoslavsky, J. & Opgenhaffen, V. (2010). The Past and Present of Corporate Complicity: Financing the Argentinean Dictatorship, Harvard Human Rights Journal 23(1): 185–203.

- Brants, C. (2007). Gold Collar Crime. In G. Geis & H. Pontell (Eds.), International Handbook of White Collar Crime. New York: Springer. pp. 309–326.

- Bretal, E. (2008). Experiencias de organización y lucha sindical en el Gran La Plata : El caso de Petroquímica Sudamericana, 1969–1973. La Plata: Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación.

- Bucheli, M. (2008). Multinational corporations, totalitarian regimes and economic nationalism: United Fruit Company in Central America, 1899–1975, Business History 50(4): 433–45.

- Bush, J. A. (2009).The Prehistory of Corporations and Conspiracy in International Criminal Law: What Nuremberg Really Said. Columbia Law Review 109(5): 1094–2081.

- Carassai, S. (2013). Los Años Setenta de la Gente Común. La Naturlización de la Violencia. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno.

- Clapham, A. (2001). Categories of Corporate Complicity in Human Rights Abuses. Hastings International and Comparative Law Review 24(3): 339–350.

- Cooney, P. (2007). The Dictatorship of the 70s, the IMF and the Shift to Neoliberalism, Revista de Economia Contemporanea 11(1): 7–37.

- CONADEP (1986). Nunca Más. The Report of the Argentina National Commission of the Disappeared. With an Introduction of Ronald Dworkin. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. In association with Index on Censorship.

- Curi, J. (1977). Arriba Argentina. Buenos Aires: Goyanarte.

- DeGuzman, M. (2010). Crimes against Humanity. In W. Schabass & N. Bernaz (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of International Criminal Law. London: Routledge p. 121–137.

- Fauchald, O. & Stigen, J. (2009). Corporate responsibility before international institutions. The George Washington International Law Review 40(4): 1025–1100.

- Feierstein, D. (2014). Genocide as Social Practice: Reorganizing Society under the Nazis and Argentina’s Military Juntas. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Feldman, G.D. (2001). Allianz and the German Insurance Business, 1933–1945, Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Feldman, G. D. & W. Seibel (Eds.) (2004). Networks of Nazi Persecution. Bureaucracy, Business and the Organization of the Holocaust. New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Forbes, Neil (2007). Multinational Enterprise, ‘Corporate Responsibility’ and the Nazi Dictatorship: The Case of Unilever and Germany in the 1930s. Contemporary European History 16(2): 149–167.

- Friedman, W. and Jones, G. (2011). Business History: Time for Debate, Business History Review 85(1): 1–8.

- Gambini, H. (2008). Historia del Peronismo. La Violencia (1956–1983). Buenos Aires: Editorial Javier Vergara.

- Grünfeld, F. (2002). The Netherlands and Argentina: Economic Interests versus Human Rights. In P. Baehr, M. Castermans-Holleman & F. Grünfeld (Eds.) Human Rights in the Foreign Policy of The Netherlands. Oxford: Intersentia. p. 23–42.