ABSTRACT

The project ‘The Norse Perception of the World’ is building a digital infrastructure to facilitate interdisciplinary research on medieval worldviews as recorded in East Norse texts. It does so by collecting spatial material, i.e. attestations of place names and other location-based data from medieval vernacular manuscripts, early prints, and runic inscriptions from fictional, non-biblical, and scientific texts dated to before 1530, and providing free access to these spatial references through a tailored back-end MySQL database and an interactive end-user interface with mapping via Leaflet and Leaflet.markercluster. This paper discusses how geocoding can be problematic when applied to pre-modern materials, as the concept of space is a temporal and social variable, especially when dealing with ideas about places abroad. The geospatial visualization employed by the project has no ambition to represent a historically correct worldview as understood by medieval Scandinavians. Rather, it is an anachronistic tool for managing and obtaining an overview of the spatial references in East Norse texts.

Introduction

Geographic Information Systems (GIS), a general framework for spatial analysis, has recently reached the field of Scandinavian philology. The interest in spatial aspects of language data analysis is growing within the discipline as the Norse Perception of the World project (see further below) reflects. However, using GIS to manage, analyse, and visualize historical, philological materials does not necessarily go hand in hand with the nature and the prerequisites of the materials in question. The aim of this article is to address a number of challenges GIS technology poses for a larger infrastructure project with a spatial focus in the field of philology. Converting heterogeneous spatial references from a variety of medieval sources to unified GIS standards for mapping and visualization purposes can affect the ways the data are perceived by end-users. We point out the discrepancies between the raw and the geocoded data that add rather than remove layers and contexts to already multi-layered historical material. Furthermore, special attention is paid to the concept of space, which is seen as a necessary starting point for discussions on medieval spatiality and worldviews. The article’s central argument is devoted to methodology and the ways conceptual anachronism can be handled when combining historical data and modern technology.

We base the article on the data and the methods used in the Norse Perception of the World project, a three-year interdisciplinary infrastructure project (IN16-0093:1) funded by the Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (2017–2020). The project’s ambition is to create an interdisciplinary resource for research on medieval worldviews and spatiality for philologists, historians, onomasticians, linguists, literary scholars, and researchers from any other related fields. The project has a clear focus on Scandinavian philology and linguistic aspects of the data, as all the project investigators have their background in medieval Scandinavian languages.

The Norse Perception of the World project

The Norse Perception of the World project sees East Norse, i.e. Old Swedish (OSw.) and Old Danish (ODa.), literature as a mine of information on how foreign lands were visualized in the Middle Ages: What places were written about and where? Are some places more popular in certain text types or at certain times? How do place names link different texts? Is there a shared concept of spatiality? How is space gendered? But the study of spatial thinking and knowledge in medieval Scandinavia and its development as an area of enquiry has for a long time been hampered by a dearth of information on spatial references in literary texts. Any research aiming to uncover what pre-modern Scandinavians understood about places abroad requires as a minimum an index of foreign place names and other location-based data in East Norse medieval fictional, non-biblical literature from before 1530, an infrastructure that has not existed until now.

The project’s text corpus comprises parchment and paper manuscripts and fragments, early printed books, and medieval runic inscriptions. Medieval East Norse literature covers a wide range of genres. However only the following religious and secular works that we assume contain relevant foreign spatial references have been incorporated into the corpus: devotional works, such as legends, miracles (often found in exempla in sermons); prayers; dreams, visions, and revelations (dominated by the figure of St Birgitta); poems; didactic works such as drama, sermons, and pilgrim guides (of which there is just one, in ODa.); romances; encyclopaedic and didactic works, such as proverb collections; chronicles and histories, and travel tales. The excluded material covers diplomas and charters, law texts, and Biblical texts, because these texts mainly mention domestic places (diplomas) or very few spatial references (law texts) or Biblical places that hardly demonstrate a specifically Scandinavian view of the world (Biblical texts).

The overall aim of the project is thus to create a research infrastructure. The infrastructure includes three main components: a tailored back-end MySQL database containing the data, Norse World (https://norseworld.nordiska.uu.se/), an interactive map resource based on the Leaflet library (https://leafletjs.com/), and a REST-API, a separate back-end application that allows end-users to access the database when making queries through the map resource. The REST-API uses JSON as its open standard format and is compatible with both GeoJSON and JSON-LD. Furthermore, the interface fits seamlessly in with major offline open-source GIS applications such as QGIS. All of the mentioned components use well-known, open-source frameworks and programming languages accessible to a wide majority of amateur and professional developers allowing them to understand the code and further develop the resource.

Scandinavian philology is an interdisciplinary field that touches upon a number of disciplines that pioneered spatial analysis via GIS in the humanities, such as history, archaeology, and literary studies. When devising the project we have found several sources of inspiration from neighbouring fields, for instance the Icelandic Saga Map project (http://sagamap.hi.is/is/) that aims to facilitate new readings of the Old Norse Sagas of Icelanders. The project provides a multimodal resource where the edited text of the sagas is linked to a map of attested place names and other information such as images of places mentioned in the sagas. The use of the Leaflet library for interactive mapping in the Norse World resource has been inspired by the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire project (DARE; http://dare.ht.lu.se/) that maps archaeological and historical sites of the period (Åhlfeldt, Citation2013). The DARE platform has been created in cooperation with the Pelagios initiative (http://commons.pelagios.org/) that aims to aggregate and interlink large amount of historical location-based datasets. We are however not aware of other spatial infrastructure projects within the field of philology that are close in scope or design to the Norse World project. The Norse World infrastructure including the interactive end-user interface is completely new, the first of its kind, and not just a repackaging of pre-existing material. The Norse World website and the REST-API was launched on 7th November 2018.

Data and metadata

The article makes use of the data created in the Norse Perception of the World project, namely a large corpus of geocoded attestations of foreign place names and other non-proprial location-based data from medieval East Norse texts. In this context, foreign means the areas outside the current, modern-day borders of Sweden and Denmark. The place names are seen as a relatively homogeneous category comprising nominal phrases that contextually identify single referents. ODa. Paris (Paris), OSw. Ryzland (Russia), and OSw. Rødha havet (The Red Sea) are prototypical examples of names in the corpus. Other location-based data comprise a number of non-proprial categories such as inhabitant designations, e.g. OSw. amalechite ‘Amalekite’; origin designations, e.g. ODa. lejdisk ‘type of cloth from Leiden’; adjectives, e.g. ODa. thythisk ‘German’; languages, e.g. ODa. grækesk ‘Greek’, as well as folk etymologies of bynames, and other appellatives that contain geographical information, e.g. Sunamitis ‘of Sunam’.

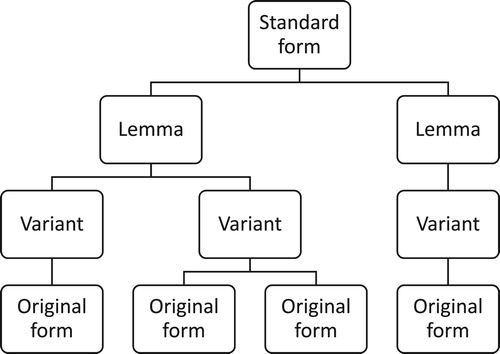

Each of these data items is attested in the corpus within an immediate textual context of varying length. A typical attestation will for example include a prepositional phrase that the data item is a part of, e.g. OSw. til egyptum ‘to Egypt’, or more commonly the necessary context to include further relevant details about the place mentioned, e.g. type of locality as in OSw. Thet hwss heyter taffwesta borg ‘the castle is called Hämeenlinna (Tavastehus)’. The raw attestation data are processed in a number of ways emphasizing different aspects of the material, e.g. spelling variation or name formation. The unprocessed and processed data thus fall into a data hierarchy with attestations at the bottom and the so-called standard forms at the top of the pyramid ().

Figure 1. Data hierarchy. Original forms, variant forms, lemma forms, and standard forms in the Norse Perception of the World project data.

The attestation forms, e.g. egiptum (Egypt) and taffwesta borg (Hämeenlinna/ Tavastehus) above, are called original forms. These forms represent words as they appear in the manuscript or any other relevant source and transcribed at the diplomatic level, here provided in italics with any occurring abbreviations expanded in roman type (not italicized). An original form is then normalized in two ways as a variant form and a lemma form respectively. The idea behind variant forms is to offer an overview of spelling variation in the material which otherwise is hard to access in hundreds of attestations of various length. The variants are thus based on one or more similar attestations that occur in one or more manuscripts of one or more texts. The normalization at this level includes capitalization of the initial letter and case adjustment as the form is always provided in the nominative, cf. the variant form Egiptus (nominative) and the original form egiptum (Egypt, Latin accusative case). The lemma form is constructed on the basis of relevant variant forms and original forms, as well as corresponding attestations in other sources. Spelling variation is of no interest at this level of normalization. Name and word formation lie at the heart of the lemmatization we use. For example, the simplex form Egyptus (Egypt) and the compound forms OSw. Egyptaland and ODa. Egipterike (Egypt) represent three different lemma forms associated with the locality Egypt.

OSw. and ODa. lemma forms are finally clustered around the localities they refer to by means of so-called standard forms. The standard form comprises the English translation of the word or the most commonly used form of the place name in the English language, e.g. Egyptian (inhabitant designation) or Mediterranean Sea. Thus, the standard form provides a link between the language data, attestations, variant and lemma forms, and the metadata associated with localities, e.g. type of locality and geodata. In the database, the raw attestation data are further linked to other types of metadata, e.g. that on the source (manuscript, early print or a runic inscription), the text, and the edition the attestation is excerpted from, and by that to details on literary genre, dating, repository, and so on. As of 20th December, 2018, the corpus that is still under construction comprises over 3006 attestations associated with more than 541 localities.

Methods

The data are gathered through close-reading of ODa. and OSw. texts written before 1530 in editions and manuscripts. The majority of the published material has no indexes, making searching and excerpting difficult. ODa. texts have been edited and published by several different societies, such as Samfund til Udgivelse af Gammel Nordisk Literatur, Universitets-Jubilæets danske Samfund (https://ujds.dk/), and Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab (https://tekstnet.dk). The principal edition series for OSw. is Svenska fornskriftsällskapets samlingar (http://svenskafornskriftsallskapet.se/). It is necessary to point out that the project team considers digitizing and OCR-reading of the published material unfeasible at the moment since OCR-reading for earlier stages of Scandinavian languages is underdeveloped.

The data have been geocoded using standard open-source geographical databases and gazetteers such as Geonames (http://www.geonames.org/) and iDAI.gazetteer (https://gazetteer.dainst.org/). Geonames contains information mainly on present-day natural features, political and other entities such as countries, cities, and so on. Moreover, the database includes data on features that have ceased to exist, e.g. Ancient Corinth (http://www.geonames.org/264638/arkhaia-korinthos.html). iDAI.gazetteer is a historical gazetteer in the sense that it contains geodata associated with pre-historical sites, objects and other material from different periods of antiquity in a number of databases of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI). In those cases where Geonames lacks geodata on certain locations we employ the data from iDAI.gazetteer, e.g. Antioch on the Orontes (https://gazetteer.dainst.org/app/#!/show/2283111) or Alabanda (https://gazetteer.dainst.org/app/#!/show/2107962). The rationale behind the gazetteer choice is that there are simply no gazetteers with a pre-medieval and medieval focus large enough to accommodate the project’s needs covering all the places outside Sweden and Denmark mentioned in the East Norse medieval literary texts. For instance, the Pelagios project (http://commons.pelagios.org/2013/10/a-web-of-gazetteers/) exclusively devoted to historical places is incorporating more and more medieval material, but unfortunately its scope is still insufficient. For this reason, the coordinates of modern-day (political) entities have often been used, such as France (http://www.geonames.org/3017382/republic-of-france.html) for OSw. Frankarike (Frankish Empire, Kingdom of France, see further in Uniformity of data).

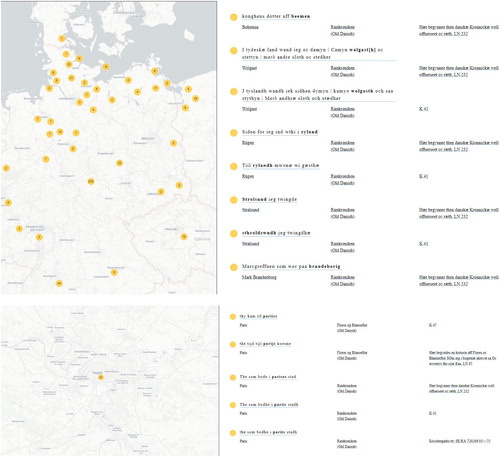

Using the Leaflet Library and the Leaflet.markercluster plugin (https://github.com/Leaflet/Leaflet.markercluster) the project utilizes interactive GIS to map the attestation data. The focus lies on quantitative aspects of the data, i.e. how frequently localities are mentioned in the corpus (). The end-user can explore the resource interactively using simple search, advanced search with a number of filters or just by moving around, zooming in and out the map and clicking on clusters. The filters available are based on most of the collected metadata, e.g. lemma forms, dating, genre, and so on (see further in Data and metadata). The data, filtered or not, can be exported for further offline analysis.

Figure 2. Data clustering in the Norse World interactive map including a close-up of the Paris area © 2019 Norse World, © Leaflet, © OpenStreetMap, © CartoDB. The figures in the map represent aggregations of attestation frequencies, i.e. how often clusters of spatial references or individual spatial references (e.g. Paris) are attested in the East Norse corpus.

Methodologically, the project thus collects data that are scattered and otherwise difficult to access, and sorts and presents them in a uniform manner. However, this way of approaching data inherently associated with GIS as a framework for spatial analysis can be seen as an overgeneralization or even as misleading and therefore methodologically problematic when applied to historical, philological material (see further in Uniformity of data).

In this paper, we employ qualitative analysis to analyse the consequences of the data collection and data visualization methods used in the current project for any subsequent scholarly study based on the infrastructure we are building. The starting point of the analysis is the definition of the key concepts such as space, geocoding, paradox of representation, and anachronism. Based on these definitions we interpret the prerequisites for spatial analysis in relation to the project’s data and metadata. The main emphasis of the analysis lies on establishing the discrepancies between the goal of the project – to build a spatial infrastructure to access medieval perception of the world – and the methods for collecting and visualizing data used to achieve that goal. We explore the anachronistic choices we have made to make the material compatible with the GIS technology and the ways this has affected the data and potentially the results of studies based on the data.

Medieval macrospace in the digital age

Concept of space

The concept of space varies historically, culturally, and socially (cf. Harrison, Citation1996: 1–2). A number of studies have been carried out to show in what way modern societies perceive space by observing how space is organized or structured (e.g. using cognitive maps, cf. Orleans, Citation1973; Tuan, Citation1974: 33–44; Matei et al., Citation2001) or how it is embedded into the surrounding discourse by interviewing or surveying informants (cf. Mondschein et al., Citation2010). Working on the conceptualization and visualization of spatial thinking in the Middle Ages researchers are bound to insufficient and limited data such as contextualized evidence of place names provided by maps, literature of a variety of genres, diplomas, charters, or any other type of material (cf. the empirical part of Harrison, Citation1996). For medieval Scandinavia, the study of space is still in its infancy (Harrison, Citation1996: [iii]), and although there are studies of local concepts of space and community, ‘microspatial knowledge’ (Harrison, Citation1996; some articles in Davies et al., Citation2006), there are as of yet no studies of what Danes and Swedes knew and wrote about foreign lands, ‘macrospatial knowledge’ (touched upon in Adams, Citation2015).

In this paper we follow Harrison (Citation1996: 2–3) and distinguish between the notions of macrospace and microspace analysing the concept of space as a historical category. The macro-level of space is concerned with the cosmographical dimension of life in the Middle Ages embracing ideas about and perception of the structure and the ‘filling’ of the medieval universe at large. Although not always specifically geographically coded (cf. Harrison, Citation1996: 7) the macrospace includes foreign places outside the empirically experienced world of the medievals. On the micro-level the focus instead lies on the empirical geographical knowledge of pre-modern individuals and groups of individuals. The boundaries between the two levels of conceptualization of space are somewhat fuzzy since they are interlinked in a number of ways. Investigations into microspace are bound to be carried out within the frame of macrospatial thinking, while certain macrospatial ideas seem to incorporate (geographically speaking) microspatial features. For instance, depictions of the city plan of the medieval world centre, Jerusalem, that includes some of its urban toponymy can be placed next to world maps in the Scandinavian medieval manuscript tradition (cf. Kedwards, Citation2014: 41, 81–83).

Both the operationalization of macro- and microspace and the boundary marking between the two rely heavily onto the chosen empirical base. To opt for medieval charters instead of chronicles would certainly allow a close-up study of microspace, for example linking the mentioned witnesses and their alleged whereabouts with the information about the charter’s place of issue (Harrison, Citation1996: 177–179). Certain types of medieval maps, world maps or mappae mundi, on the other hand are traditionally seen as reflecting the macrospace of the medievals (Harvey, Citation1987: 284; Simek, Citation1990: 105, 146; Harrison, Citation1996: 4–5; see further in Visualization).

In the Norse Perception of the World project, the macrospatial idea of space serves as its overall frame. As it has been stated in the Introduction, the project’s material includes devotional works, e.g. legends, miracles, and prayers; dreams, visions, and revelations; poems; didactic works such as drama, sermons, and pilgrim guides. The contents of some of these works (such as legends, miracles, sermons, and prayers) would have been familiar even to the illiterate population, who would have been told the stories during sermons and instruction in church. Moreover, we excerpt data from romances; encyclopaedic and didactic works; chronicles and histories, and travel tales. Some of these works (chronicles, travel tales, and encyclopaedic works) would have been less familiar to the majority of the population, and probably restricted to more learned or wealthy circles although their content and the worldview that they reflected was most likely more widely known. The encyclopaedic works, such as Sydrak and Lucidarius (Knudsen, Citation1921–Citation1932; Frederiksen et al., Citation2008), are of particular interest as they are typically aimed at describing and explaining the world.

Uniformity of data: a blessing or a curse?

GIS technology owes its revolutionary potential to standardized ways of managing spatial data and their attributes. The main advantage of GIS is that it provides a technical framework that helps to structure, organize, and visualize heterogeneous data so that they can be spatially analysed, qualitatively or quantitatively, and to combine numerous datasets addressing different aspects of spatial phenomena (cf. Gregory and Geddes, Citation2014: xiv). However, this technological advantage has a potential to become an obvious drawback when applied to historical materials. The raw spatial references excerpted from primary sources have to be geocoded, i.e. provided with corresponding geographical coordinates. Geocoding archaeological sites is, for instance, relatively unproblematic, since the site itself has a precise and identifiable location on the Earth’s surface irrespective of what people of a certain historical period imagined about the place or its whereabouts. Embarking on someone’s mentality or cognitive maps, i.e. ideas about places and their positions within an unidentified coordinate system, leads to far less straightforward choices when it comes to geocoding and visualization techniques.

The raw data excerpted for the Norse Perception of the World project come from a variety of types of sources (manuscripts, early prints, and runic inscriptions), genres (e.g. romances and chronicles), literary works, languages, time periods, and so on. Most of these differences indeed are taken into account by providing appropriate metadata for each attestation. Furthermore, the material comprises mentions of places that are qualitatively different, e.g. sacral places such as churches and other places of worship or cities of particular religious significance as opposed to more secular localities (cf. Harrison, Citation1996: 11–14). Although the database provides metadata on type of locality such differences are either ignored or only attended to in attestation notes in less clear cases. Another important consequence of geocoding for visualization purposes is the ‘equalization’ of manuscript data. Traditional textual criticism has established more or less well-founded manuscript hierarchies through stemmata (e.g. Henning, Citation1954; Pipping, Citation1963; cf. discussion on place names and textual criticism in Petrulevich, Citation2016: 60–75). For example, The Chronicle of Duke Erik survives in seven medieval manuscripts of different significance. One of them, Holm. D 5 from National Library of Sweden dated to 1500–1525, is considered less significant providing e.g. the reading norge (Norway) when the rest of the material read torney ‘tourney’ (Pipping, Citation1963: ii–xi, 31). The Norway attestation from Holm. D 5 has a clarifying attestation note, but otherwise is not marked in any way as different from the rest of the attestations of Norway in the database.

Applied to the Norse Perception of the World data, geocoding thus transforms a highly heterogeneous material into a homogenous GIS compatible dataset by transferring the major differences to filters in advanced search or Notes. It can be argued that the constructed infrastructure conceals important information about the data by employing uniform procedures for geocoding and visualization and misleads the end-user in doing so. However, bringing together and ‘equalizing’ different materials creates a unique opportunity to approach spatial references on manuscript level without e.g. re-producing implicit prejudice of the past. Setting the infrastructure free from the paradigm of traditional textual criticism allows the data to speak for itself at the same time as the metadata and the attestation notes provide enough background detail to counteract the shortcomings of positivism. Through geocoding, the Norse World resource emphasizes spatial rather than material-related aspects of data and creates a brand-new synergy effect for exploring the macrospace of East Scandinavian medieval literature.

Assigning geographical coordinates to mentioned locations implies a known, relatively stable temporal and spatial frame. However, the prerequisites for such a frame are rather few in the case of the Norse Perception of the World project. Partly, this has to do with dating difficulties and the nature of manuscript culture. It is often impossible to date the composition of an East Scandinavian literary work with any accuracy since there are so few extant vernacular manuscripts from Sweden and Denmark. Without an exact dating, it is hard to determine a temporal and thus spatial point of departure for establishing coordinates for e.g. historical political entities. The East Norse fictional non-biblical texts are multi-layered, combining material from different time periods. Further, even when the work is dated, like the Eufemiavisor ‘the Euphemia lays’, three medieval romances translated into Old Swedish and dated to 1301–1312, the manuscripts containing the tales can be much younger, the oldest in the case of the Eufemiavisor is from the 1430s, the latest, from the sixteenth century (Klemming, Citation1853: 226–227). Moreover, manuscripts were used for a long time often being handed down through generations and even used for different purposes, sometimes as entertainment and at other times as historical sources (cf. Backman, Citation2017: 60–61). From a reception point of view, all the different times the locality France is mentioned in these texts could have carried different connotations and understandings of geography and macrospace when read.

In other words, the imprecise nature of the medieval macrospace is disrupted by geocoding when the exact coordinates are imposed onto a material that is ambiguous in nature. As we have touched upon in Methods there is to-date no gazetteer supplying coordinates for medieval places, either known to the medieval public through literature or established as a result of archaeological research. We are thus required to use gazetteers that do not match the focus or scope of the project, which is an inescapable compromise. At the same time, by using modern, anachronistic coordinates, we do not decide on one historical time period to be stand-in for all others. The apparent anachronism in geocoding and visualization emphasizes the purpose of it, to allow researchers to get an instant overview of large quantities of spatial references.

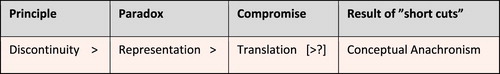

Paradox of representation and conceptual anachronism

The geocoding procedure implies a transposition of the modern concept of space taken from hard sciences into research mainly preoccupied with the past, which almost automatically leads to conceptual anachronism. Within the field of history conceptual anachronism is defined as a ‘corruption of the use of modern concepts in historical narratives’ (Poe, Citation1996: 352; cf. Fairburn, Citation1999: 203–204.). Anachronisms of this kind violate one of the key principles of the historical scholarship, that of discontinuity which postulates the inherent difference between the past and present (Poe, Citation1996: 347–348). As Poe (Citation1996: 349–354) puts it conceptual anachronisms can be seen as research compromises emanating from the so-called paradox of representation. The paradox itself implies a requirement of accurate historical descriptions despite the lack of conceptual links between the past and present. Applying modern concepts in historical research, termed translation by Poe (Citation1996: 350), can be seen as a way of eliminating or resolving the paradox (). Conceptual anachronisms can in other words be both ‘good’ and ‘bad’, while certain types of research, e.g. pattern-searching scholarship based on large datasets, even infer a certain portion of conceptual anachronism. However, there are no clear-cut criteria to distinguish between ‘sensible compromises’ and ‘heavy-handed corruptions’ in the world of conceptual anachronism (Poe, Citation1996: 354–355).

Figure 3. Paradox of representation leading to conceptual anachronism, adapted after Poe (Citation1996: 354 Table 3): Scientific Programs and Anachronism.

For the Norse Perception of the World project, the compromises involving conceptual anachronism are inescapable, since substantial amounts of attestation data from historical sources are made compatible with GIS standards. Furthermore, the focus lies on the frequencies of mentions to facilitate quantitative analyses of the collected data. We consider the compromises we made sensible, but it is of crucial importance for the end-user to be aware of the limitations of the Norse World resource, and, more importantly, the choices the project team has made to collect, geocode, and visualize data.

Geospatial visualization as a method and an analytical tool

The Norse World infrastructure visualizes spatial data through interactive clustering, an ‘upgraded’ version of conventional point data mapping (cf. Börner, Citation2015: 52–55). This presentation mode forms a contrast to traditional qualitative analysis of manuscripts and early prints in the field of Scandinavian philology. Shifting the focus from qualitative to quantitative aspects of philological data opens new possibilities to explore the material that did not exist before, reveals patterns that otherwise go unnoticed, and through this changes the way we approach historical spatial information and the world it represents (cf. Foka and Gelfgren, Citation2017: 150 with references; see above). For instance, East Norse multitext manuscripts have rarely been edited as single entities since traditional textual criticism instead favours publishing single works preserved in multiple handwritten sources (with few exceptions, e.g. Frederiksen et al., Citation1993–Citation2008; Andersson, Citation2006; Arvidsson’s electronic edition of Holm. D 4 (2016) at Menota, http://clarino.uib.no/menota/page). The Norse World platform opens an unprecedented opportunity to access and analyse spatial references fetched from one or more multitext manuscripts. However, thorough contextualization is needed to clarify why we consider utilizing the Leaflet.markercluster plugin as the ultimate visualization technique for the current project.

Previous research has almost exclusively viewed medieval world maps or mappae mundi as contemporaneous visualizations of medieval macrospace (Harvey, Citation1987: 284; Simek, Citation1990: 105, 146; Harrison, Citation1996: 4–5). In Scandinavian manuscripts, medieval maps of this kind are very rare. As far as we are currently aware, the East Norse material includes only one such map found in a post-medieval manuscript of the Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Holm. M 306 dated to 1584 (Toldberg, Citation1966: cols 309–311). Thus, this way of picturing the world is perhaps non-applicable to the area of investigation. Moreover, recent scholarship has come to question the assumption above. Studies of world maps as a part of medieval manuscript culture reveal that they are re-produced under ‘Geometry’, a category that embraced knowledge about the proportions of the world and place names (Kedwards, Citation2014:17 with references; cf. Rouse, Citation2014 with references). The cosmographical, macrospatial dimensions of mappae mundi perceived as such by their users in the past can be challenged as at least partly anachronistic.

Furthermore, we argue that the notion of space in the Middle Ages is to be abstracted from medieval textual material, rather than medieval visualizations. There are reasons to believe that geographical and spatial knowledge of the time was textually rather than visually coded (Rouse, Citation2014: 18–19, 26). Medieval literature thus contains written rather that drawn maps allowing protagonists to move in a linear fashion from one place to another. The conveyed spatial references constitute an inseparable part of a medieval text, since the text binds together spatial and geographical information at the same time as place names and other location-based material link different parts of the text, or different texts.

The geospatial visualization employed by the Norse World resource by no means has the ambition to represent a historically correct worldview of medieval Scandinavians. Rather, it serves as a method of managing and obtaining an overview of large amounts of spatial data. At the same time, the employed clustering technique can be utilized as an analytical tool to facilitate comparisons of data distribution in different types of material. Thinking visually about location-based data irrespective of their origin can be seen as a contemporary norm: complex information is distilled down to a visual argument that can be shaped and defined as the researcher needs (Wrisley, Citation2014).

Conclusions

The goal of the Norse Perception of the World project is to build a digital infrastructure to facilitate interdisciplinary research on medieval worldviews of East Scandinavia. Collecting raw spatial material, i.e. attestations of place names and other location-based data from a variety of manuscripts, early prints, and runic inscriptions, is the first necessary step the researcher has to take when unfolding the temporally and socially variable macrospace of East Norse literature. The project does so by providing free access to spatial references of the fictional, non-biblical medieval texts from Sweden and Denmark through a tailored back-end MySQL database.

Visualization of large spatial datasets by geocoding and mapping is an inspiring and innovative way of uncovering patterns one did not know existed. However, the process of geocoding appears problematic when applied to pre-modern materials, since it implies conceptual as well as other types of anachronism. Employing GIS-tools thus means accepting anachronism as a necessary research compromise. Accordingly, the Norse World visualization is not meant to be a truthful representation of East Scandinavian medieval macrospaces. Foka and Gelfgren (Citation2017: 160) see historically correct digital simulations and representations as a utopia, which is a good summary of our experiences from the Norse Perception of the World project. Instead, the visualization techniques used are meant to serve as a methodological and analytical help for researchers enabling them to for example get an overview of the data and compare results of different queries. The digital tools that interactive GIS provides create brand-new opportunities to approach historical philological data in conceptually different ways, e.g. quantitatively or without reproducing the paradigm of traditional textual criticism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude for the input of project participant Simon Skovgaard Boeck, Department of Scandinavian Languages, Uppsala University, as well as the database and web-design development undertaken by Jorunn Hartmann, Rasmus Ljungström, and Andreas Lecerof at the Office of System Development, Uppsala University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on the contributor

Alexandra Petrulevich holds a PhD in Scandinavian languages from the Department of Scandinavian Languages at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her main research interests include digital humanities, Scandinavian philology, and onomastics. She coordinates GIS for language study (LanGIS), a two-year network initiative in spatial humanities at the Faculty of Languages, Uppsala University. She is currently involved in the Norse Perception of the World project. Twitter: @petrulevich

Alexandra Petrulevich holds a PhD in Scandinavian languages from the Department of Scandinavian Languages at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her main research interests include digital humanities, Scandinavian philology, and onomastics. She coordinates GIS for language study (LanGIS), a two-year network initiative in spatial humanities at the Faculty of Languages, Uppsala University. She is currently involved in the Norse Perception of the World project. Twitter: @petrulevich

ORCID

Alexandra Petrulevich http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8478-2040

Agnieszka Backman http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9233-0407

Jonathan Adams http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3890-4630

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, J. (2015) “The Life of the Prophet Muḥammad in East Norse” In Adams, J. and Heß, C. (Eds) Fear and Loathing in the North: Jews and Muslims in Medieval Scandinavia and the Baltic Region Berlin: De Gruyter, pp.203–238.

- Åhlfeldt, J. (2013) “Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire (DARE)” Patristica Nordica Annuaria 28 pp.18–21.

- AM 736 I 4to. Geographical and cosmographical book (1290–1310) Den Arnamagnæanske Samling (AM 736 I 4to), Copenhagen.

- Andersson, R. (2006) Sermones sacri Svecice, the sermon collection in Cod. AM 787 4o. Uppsala: Svenska fornskriftsällskapet.

- Backman, A. (2017) “Handskriftens materialitet: Studier i den fornsvenska samlingshandskriften Fru Elins bok (Codex Holmiensis D 3)” (PhD thesis) Uppsala University Available at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn = urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-315621 (Accessed: 26th June 2018).

- Börner, K. (2015) Atlas of Knowledge: Anyone Can Map Cambridge, London: The MIT Press.

- Davies, W., Halsall, G. and Reynolds, A. (Eds) (2006) People and Space in the Middle Ages, 300–1300 Turnhout: Brepols.

- Fairburn, M. (1999) Social History: Problems, Strategies and Methods Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Foka, A. and Gelfgren, S. (2017) “Visualisering som verktyg och metod för historieforskning” In Erixon, P-O. and Pennlert, J. (Eds) Digital humaniora – humaniora i en digital tid Göteborg: Daidalos, pp.147–164.

- Frederiksen, B.O., Bergsagel, J. and Skog, I. (1993, 2008) A Danish teacher's manual of the mid-fiftheen century (Cod. AM 76, 8⁰). Lund: Lund University Press/ Kungl. Vitterhets-, Historie- och Antikvitets Akademien.

- Gregory, I.N. and Geddes, A. (2014) “Introduction: From Historical GIS to Spatial Humanities: Deepening Scholarship and Broadening Technology” In Gregory, I.N. and Geddes, A. (Eds) Toward Spatial Humanities: Historical GIS and Spatial History Bloomington: Indiana University, pp.ix–xix.

- Harrison, D. (1996) Medieval Space: The Extent of Microspatial Knowledge in Western Europe During the Middle Ages Lund: Lund University Press.

- Harvey, P.D.A. (1987) “Medieval Maps: An Introduction” In Harley, J.B. and Woodward, D. (Eds) The History of Cartography Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp.283–285.

- Henning, S. (Ed.) (1954) Siælinna Thrøst. Første delin aff the bokinne/ som kallas siælinna thrøst. Efter cod. Holm. 108 (f.d. cod. Ängsö) Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Holm D 5. Svenska krönikor (1500–1525), MS, National Library of Sweden (D 5), Stockholm.

- Holm M 306 (1584) MS, National Library of Sweden (M 306), Stockholm.

- Kedwards, D. (2014) “Cartography and Culture in Medieval Iceland” (PhD thesis) University of York Available at: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/8489/ (Accessed: 25th June 2018).

- Klemming, G.E. (1853) “Efter-skrift” In Ahlstrand, J.A. (Ed.) Hertig Fredrik af Normandie, en medeltids-roman Stockholm: pp.223–228.

- Knudsen, G. (Ed.) (1921–1932) Sydrak: efter haandskriftet Ny Kgl. Saml. 236 4to Copenhagen: Universitets-Jubilæets Danske Samfund.

- Matei, S., Ball-Rokeach, S.J., and Linchuan Qiu, J. (2001) “Fear and Misperception of Los Angeles Urban Space. A Spatial-Statistical Study of Communication-Shaped Mental Maps” Communication Research 28 (4) pp.429–463. doi: 10.1177/009365001028004004

- Mondschein, A., Blumenberg, E. and Taylor, B. (2010) “Accessibility and Cognition: The Effect of Transport Mode on Spatial Knowledge” Urban Studies 47 (4) pp.845–866. doi: 10.1177/0042098009351186

- Orleans, P. (1973) “Differential Cognition of Urban Residents: Effects of Social Scale on Mapping” In Downs, R.M. and Stea, D. (Eds) Image and Environment: Cognitive Mapping and Spatial Behavior London: Arnold, pp.115–130.

- Petrulevich, A. (2016) “Ortnamnsanpassning som process: En undersökning av vendiska ortnamn och ortnamnsvarianter i Knýtlinga saga” (PhD thesis) Uppsala University Available at: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn = urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-281635 (Accessed: 26th June 2018)

- Pipping, R. (1963) Erikskrönikan enligt Cod. Holm. D.2 jämte avvikande läsarter ur andra handskrifter. Uppsala: Svenska fornskriftsällskapet.

- Poe, M. (1996) “Butterfield’s Sociology of Whig History: A Contribution to the Study of Anachronism in Modern Historical Thought” Clio 25 (4) pp.345–363.

- Rouse, R. A. (2014) “What Lies Between?: Thinking Through Medieval Narrative Spatiality” In Tally, R.T. (Ed.) Literary Cartographies: Spatiality, Representation, and Narrative New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.13–30.

- Simek, R. (1990) Altnordische Kosmographie: Studien und Quellen zu Weltbild und Weltbeschreibung in Norwegen und Island vom 12. bis zum 14. Jahrhundert Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Toldberg, H. (1966) “Mandevilles rejse” In Granlund, J. (Ed.) Kulturhistoriskt lexikon för nordisk medeltid från vikingatid till reformationstid. Vol. 11 Malmö: Allhems förlag, cols, pp.309–311.

- Tuan, Yi-Fu (1974) Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Wrisley, D.J. (2014) “Spatial Humanities: An Agenda for Pre-Modern Research” Porphyra 22 pp.96–107.