abstract

This article examines the relations between workplace and local labor regimes, global production networks (GPNs), and the state-led creation of expanded markets as spaces of capitalist regulation through trade policy. Through an examination of the ways in which labor regimes are constituted as a result of the articulation of local social relations and lead-firm pressure in GPNs, the article examines the limits of labor provisions in European Union trade policy seeking to ameliorate the worst consequences of trade liberalization and economic integration on working conditions. The article takes as its empirical focus the Moldovan clothing industry, the leading export-oriented manufacturing sector in the country. Trade liberalization has opened up a market space for EU lead firms to contract with Moldovan-based suppliers, but in seeking to regulate labor conditions in the process of trade liberalization, the mechanisms in place are not sufficient to deal with the consequences for workers’ rights and working conditions. Indeed, when articulated with national state policy formulations seeking to liberalize labor markets and deregulate labor standards, the limits of what can be achieved via labor provisions are reached. The EU’s trade policy formulation does not sufficiently take account of the structural causes of poor working conditions. Consequently, there is a mismatch between what the EU is trying to achieve and the core labor issues that structure social relations in, and labor regimes of, low-wage labor-intensive clothing export production for EU markets.

Recent years have seen a closer engagement between research on working conditions in the world economy, the globalization of production, and the state. On the one hand, research has examined the enrollment of labor in global production networks (GPNs) and the extent to which this allows agency for workers to enhance working conditions (Coe, Dicken, and Hess Citation2008; Cumbers, Nativel, and Routledge Citation2008; Coe and Hess Citation2013; Rossi Citation2013; Coe Citation2015). Attention has also been paid to deepening exploitation (Starosta Citation2016) and insecurity (Smith Citation2015c) that such enrollment brings, and conceptually to bringing together labor process theory and GPN research around workplace struggles over surplus value (Newsome et al. Citation2015; Taylor et al. Citation2015; Baglioni Citation2017). On the other hand, research has explored how GPNs are articulated with the state and how state policy and trade regulation seeks to establish new geographic frontiers for capital accumulation (Glassman Citation2011; Smith Citation2015a; see also Horner Citation2017). Together, this work has its parallels with Levy’s (Citation2008, 944) “understanding of GPNs as integrated economic political systems” (see also Arnold and Hess Citation2017).

This article bridges these debates by examining how contemporary trade policy integrates economic space and allows GPNs to expand, while at the same time seeking to regulate the labor process on which such production depends. Our argument is that an emerging new form of labor governance utilizing international labor standards in the social clauses of free trade agreements (FTAs) does not give adequate attention to the ways in which labor regimes are constituted in macroregional production networks—a constitutive process shaped in part by asymmetric interfirm power relations of GPNs and deepening trade integration. Our focus is on the European Union as a leading proponent of such social clauses, and our argument is that the social clauses are not only inadequate at protecting labor standards, but they overlook structural dynamics in GPNs (see Hauf Citation2015).

GPN concepts of interfirm governance highlight the power relations between lead firms and suppliers in the production of value, as new international divisions of labor are created by cross-border integration, and as firms and states attempt to control the labor process and manage risk (Pickles and Smith Citation2016; Smichowski, Durand, and Knauss Citation2016).Footnote1 Our focus here is on clothing production networks, which can be characterized as involving largely asymmetrical and externalized power relations between lead firms and suppliers (Gereffi Citation1994; Smith Citation2003; see also Coe and Yeung Citation2016; Havice and Campling Citation2017). As Plank and Staritz (Citation2015) and Pickles and Smith (Citation2016) have highlighted, there is an increasing role played by macroregional production networks in the clothing sector across European borders. EU trade policy is central to this process, leading to the creation of expanded markets and investment opportunities for lead firms, including in countries neighboring the European Union. At the same time, EU trade policy is seeking to regulate the potential worsening of working conditions through the adoption of International Labor Organization (ILO) core labor standards in social clauses—an approach also taken in varied forms by the United States and Canada in their FTAs (Campling et al. Citation2016; Tran, Bair, and Werner Citation2017). This represents a new form of global labor governance that the European Union for its part has been rolling out in all its post-2011 trade agreements: the so-called trade and sustainable development (TSD) framework that as of July 2017 was contained in finalized agreements with nineteen countries. The core labor standards refer to eight fundamental ILO conventions that aim to prevent child labor, forced labor, workplace discrimination, and the suppression of free association and collective bargaining. Together these form the cornerstone of many labor governance initiatives, including the Better Work Program of the ILO and the International Framework Agreements signed by global unions and corporations. Reliance on such core labor standards is part of a wider erosion of the ILO’s ability to regulate work in a globalizing economy (Alston Citation2004; Standing Citation2008; Hauf Citation2015), while such standards are also noted for their gender blindness (Kabeer Citation2004; Elias Citation2007). As we show, further problems are found insofar as core labor standards, even when mandated through a legally binding trade agreement, fail to articulate the most pressing issues in export-oriented production networks arising from the structural inequalities in GPNs.

Empirically, the article examines the Moldovan clothing industry: the leading export-oriented manufacturing sector in the country. Moldova signed an Association Agreement with the European Union in 2014, which includes a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with obligations around TSD involving the ILO core labor standards (Smith et al. Citation2017).Footnote2 We argue that these provisions are not sufficient to deal with labor regimes in macroregional production networks. Without taking into account the production network dynamics and historically sedimented labor regimes in shaping factory work, there is a mismatch between what the European Union is trying to achieve in its labor governance framework and the most pressing labor issues in key export sectors. We focus on three dynamics: first, structural pressures associated with contract prices and delivery times in the production network that require supplier firms to meet the exacting needs of EU lead firms and that drive the working conditions found in clothing labor regimes; second, how these working conditions reflect the historic formation of workplace and local labor regimes that are influenced by the legacies of Soviet-era production politics; and third, the impacts of national labor regulation on working conditions where the Moldovan state is seeking simultaneously to integrate EU employment and health and safety frameworks and to liberalize labor markets. In order to theorize the relations among these three dynamics, we develop a conceptualization of nested scales of labor regimes and GPN dynamics, elaborated in the following section.

The article contains new primary data on the consequences of the EU FTA in Moldova. It is based on forty-one individual and group interviews with key informants in a range of government departments, development agencies, trade unions, and industrial associations in Moldova, and with twelve enterprises in the clothing sector, including the largest supplier firms, in addition to thirty-eight interviews in Brussels with European Commission (EC) officials, industry specialists, and trade unions. Interviews are referred to by a numerical code to ensure the anonymity of informants (e.g., M1). The clothing enterprises were selected to capture the range of positions of firms in the Moldovan production network, with access negotiated via the main industry associations.Footnote3 Enterprises were either Moldovan owned, joint ventures, or involved 100 percent (often Italian) foreign ownership. Larger former state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which involved all three ownership types, operated as lead suppliers, and each employed between 250 and 800 workers, although all had seen considerable reductions in employment over the last ten years. These firms mainly undertook export production with some limited domestic market activity. Smaller, often newer, firms were largely Moldovan owned, employed between 15 and 150 workers, and sometimes combined export and domestic-market production. Respondents within enterprises were either the managing director or other senior managers (e.g., production managers). In three enterprises, group interviews were undertaken with the entire senior management team. Worker representatives from the six largest former SOEs, with access negotiated via the industrial trade union, and branch and confederal trade unions, were interviewed. Triangulation across management, worker, and sectoral specialists was achieved by careful cross-checking of emergent interview themes, and with analysis of national official data and publications.

In the next section we discuss the labor provisions in the EU’s trade policy and our analytical framework on labor regimes and GPNs. This is followed by an analysis of deepening export integration, lead-firm pressures and the legacies of Soviet-era labor relations in shaping Moldovan labor regimes—the conditions of which constrain the ability of the EU’s labor provisions to deal adequately with working conditions. The article then concludes.

Trade Policy and the Regulation of Labor in Global Production Networks

The EU’s trade policy and economic integration framework with its neighboring states has focused on the creation of new economic opportunities for EU capital in the geographically proximate but lower labor cost zones of Eastern and Central Europe and North Africa, often to reduce production costs of industrial goods for EU markets (Smith Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Campling Citation2016; Pickles and Smith Citation2016). Trade policy has been key to a process of captive and uneven economic integration to create a macroregional space of trade and economic integration.Footnote4 At the same time, the European Union has sought to regulate the worst excesses of poor working conditions arising in part from trade liberalization via labor provisions in its FTAs. Understanding this articulation between trade liberalization and the regulation of labor standards therefore requires analysis of how lead firms in core markets shape labor regimes in producing countries (Campling et al. Citation2016). Two dynamics are critical: (1) how conditions are influenced by commercial and contracting pressures in the production network and (2) the legacies of Soviet-era labor regimes in shaping working practices under today’s different conditions. Before turning to a framework for our analysis, we review the EU’s trade policy with Moldova in the context of the EU’s trade–labor linkage.

Labor Provisions in EU Trade Agreements

Moldova and the EU signed an Association Agreement in June 2014, which was provisionally applied until its full implementation in 2016. There are two main elements to the agreement: a political agreement for progressive domestic reform and engagement, and the establishment of a DCFTA over a ten-year period. The Association Agreement aims to build good neighborly relations and includes a wider set of provisions than a standard FTA. The Association Agreement has been a mechanism by which pro-EU political forces and post-2009 governments in Moldova sought to transform the country’s external relations in the face of continuing Russian influence in and beyond the so-called frozen conflict in the Dniester region, to which the DCFTA was applied only in January 2016 (Secrieru Citation2016). The EU’s recent deep and comprehensive approach to its trade relations with neighboring states reflects the expansion of earlier trade agreements from just tariff liberalization relating to industrial goods, to include agriculture and services, and the alignment of countries’ regulatory frameworks to those of the European Union—removing a range of nontariff barriers and mirroring competition policy, investment provisions, and industrial and agricultural standards. Such DCFTAs are proliferating across and beyond the Euro-Mediterranean region and represent an attempt to create an integrated market space and investment zone for EU capital on the margins of Europe (Smith Citation2015b).

This deepening of economic and trade integration has been accompanied by the inclusion of labor provisions in the agreements. There are two primary mechanisms by which labor provisions and working conditions are regulated in the current Association Agreement. The first is a TSD chapter in the DCFTA. This chapter contains a series of commitments to upholding labor and environmental standards. The labor provisions focus primarily on (1) “respecting, promoting and realizing in their law and practice and in their whole territory” the ILO core labor standards and other ratified ILO conventions, (2) “consider[ing] the ratification of the remaining” conventions, (3) not using violations of labor standards to create comparative trade advantages, and (4) not using labor standards for “protectionist trade purposes” ().Footnote5 The labor provisions also involve seeking “greater policy coherence between trade policies … and labor policies,” and the promotion of ethical trade and corporate social responsibility.Footnote6 Finally, the agreement also establishes a number of institutional mechanisms centered on civil society involvement and capacity-building to “ensure effective implementation” but does not include trade sanctions (European Commission Citation2015).Footnote7

Table 1 The Evolution of EU–Moldova Trade Agreements and Labor Provisions

Second, the nontrade chapters of the Association Agreement contain a number of provisions requiring the approximation of Moldova’s legislation to that of the European Union, the so-called acquis communautaire. This includes a process of regulatory approximation of eight EU directives relating to labor law, six EU directives relating to antidiscrimination and gender equality, and twenty-five directives relating to health and safety at work (Emerson and Cenuşa Citation2016; Smith et al. Citation2017).

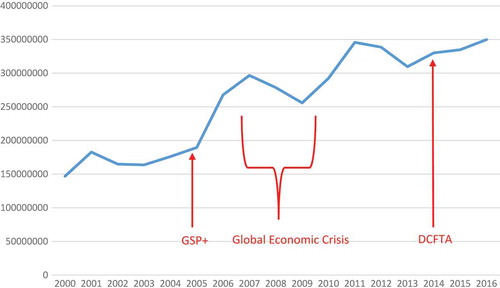

The Association Agreement has replaced and extended arrangements that were established in earlier EU–Moldova trade arrangements (). Each enabled the progressive application of preferential duties and tariff liberalization subject to the ratification and implementation by the Moldovan government of international agreements on labor standards, human rights, good governance, and sustainable development. Consequently, by the time the Association Agreement was signed, Moldova had ratified all 8 ILO core conventions, all 4 governance conventions, and 30 (out of 177) ILO technical conventions. The core conventions are the primary mechanisms by which the European Union seeks to regulate working conditions in its trade agreements. In the Moldovan case, refusal to ratify labor conventions is less a problem (in contrast to other cases, such as South Korea) (see Harrison et al. CitationForthcoming). Translating them into meaningful practice has, however, been the issue.

At the heart of this framework is a contradiction between the opening of economic space for EU capital and the inability of the labor provisions to regulate the extant working conditions in labor-intensive export industries. As we demonstrate, the working conditions created in the context of trade liberalization are not dealt with adequately by the ILO core labor standards framework. There are strong parallels with the limits of other programs reliant on ILO labor standards and the decent work agenda such as the Cambodia Better Factories and wider Better Work Programs. Research has found that these programs are unable to deal adequately with “atomised trade unions and disempowered workers with low wages and insecure jobs” (Arnold and Shih Citation2010, 409) and the structural underpinnings “causing indecent work” (Hauf Citation2015, 150). As Rossi (Citation2015) also found, the integration of the Better Work initiative into a US–Haiti trade agreement works most effectively because of the existence of sanctions to withdraw trade preferences for noncompliant factories. Such sanctions do not appear in the more promotional (ILO Citation2013) approach of EU labor provisions. They therefore offer little recourse to hard law in the regulation of working conditions in export production.

Labor Regimes and GPNs

In order to understand these contradictory dynamics, it is helpful to consider employment relations as the outcome of local and workplace labor regimes as they are shaped in combination with the commercial pressures placed on suppliers by lead firms in GPNs. Local and workplace labor regimes can be conceptualized as historically formed, multiscalar phenomena resulting from the articulation of struggles over local social relations intersecting with lead-firm contracting practices in GPNs at the workplace scale (Jonas Citation1996; Coe and Hess Citation2013; Pattenden Citation2016). But the labor provisions in EU trade agreements largely fail to address this political economy of labor relations, which limit the impacts of those provisions.

A range of approaches exist to labor regimes and global production. First, in an analysis of the clothing sector, Anner (Citation2015a) has focused on three macrotypological characterizations of labor control regimes: state labor control regimes (including an authoritarian variant found in China and Vietnam); market labor control regimes in which unfavorable labor market conditions discipline labor; and employer labor control regimes, which involve “highly repressive employer actions against workers” (ibid., 293). Anner highlighted two effects of the increasing monopsony of power in clothing GPNs in which a small number of buyers leverage power over a large number of suppliers: “the ability of lead … firms to set the price paid to smaller production contractors has generated persistently low wages [and] … the push for lead firms to demand just-in-time inventory has generated a work-intensity crisis in workplaces” (ibid., 297). These lead-firm dynamics are rendered across the different typologies of labor regimes that he identifies. In making this argument, Anner (Citation2015a) extended Burawoy’s (Citation1985) approach to the politics of production, combining an understanding of both the labor process and forms of labor power reproduction (see also Peck Citation1996).

Second, Jonas (Citation1996, 323) framed local labor control regimes as “a stable local institutional framework for accumulation and labor regulation constructed around local labor market reciprocities” and as “an historically contingent and territorially embedded set of mechanisms” seeking to coordinate production, work, and labor reproduction (ibid., 325; see also Kelly Citation2002; Baglioni Citation2017). However, while attentive to the proximate factors influencing workers’ lives, Jonas said less about the wider structures of corporate power in GPNs, which we argue are central to understanding the GPN–labor regime nexus.

Consequently, we develop a nested scalar approach to understanding labor regimes and production politics, and how they articulate with labor provisions embedded in international trade agreements (see Pattenden Citation2016) (). We stress the ways in which the nested scalar dynamics of labor regimes are shaped by commercial pressures in GPNs and historically inflected with past workplace governance relations, in our case in the context of post-Soviet societies, and how they originate from spatial networks of labor governance, including state and nonstate actors. This sense of evolutionary change has parallels with MacKinnon’s (Citation2017) analysis of labor adaptation to economic change. The starting point is the workplace labor regime in which the labor process provides a focus on the “dynamics of control, consent, and resistance” (Thompson and Smith Citation2011, 11; see also Taylor et al. Citation2015) and at which point the organization of labor in the production process provides the basis for the creation and appropriation of surplus value ().Footnote8 Second, workplaces are integrated into a wider local and national political economy, regulated by state policy on labor, employment rights, and working conditions.Footnote9 Drawing on Jonas (Citation1996), this is what Pattenden (Citation2016, 1814), referred to as the mesolevel “local labor control regime”—the concrete and specific mechanisms in a locality “that shape labor’s material and political conditions” (ibid.; see also Werner Citation2016). Third, workplace dynamics have to be understood as part of wider production networks through which the configuration of power relations between suppliers and lead firms is deployed. These power relations structure the class, race, and gender dynamics that constitute labor regimes in the workplace (Muszynski Citation1996; Taylor et al. Citation2015). In the case of the European clothing sector, lead firms (buyers) are faced with increasing market competition and interfirm struggles to secure profits from what in recent years has been a relatively stagnant consumer market.Footnote10 The result has been an increased concentration of power among a smaller group of retailers in many EU countries and cost pressures down the value chain impacting on suppliers. As research on the sector has shown, these interfirm relations are characterized by significant power asymmetries between lead firm and suppliers (Gereffi Citation1994; Smith Citation2003; Werner Citation2016), which are embroiled in wider networks of power struggles between social actors (Arnold and Hess Citation2017).

Existing research on labor regimes and GPNs tends to provide either a classification and typological analysis of contrasting regimes in differing national and political–economic contexts (Anner Citation2015a) or an analysis of different value chain configurations that create different employment patterns (Lakhani, Kuruvilla, and Avgar Citation2013). A framework for understanding labor provisions in FTAs as a new form of labor governance requires, we argue, an approach that focuses on labor process dynamics, the nested spatial networks of labor governance, and how they are integrated into GPNs (Newsome et al. Citation2015). Understanding the dynamics underpinning the formation of workplace labor regimes is critical to an exploration and identification of the reach and mismatch of labor provisions in trade agreements. This approach develops existing GPN analyses of labor that have focused on labor agency (e.g., Coe and Hess Citation2013; Coe Citation2015). It adds to existing labor regimes research with a specific focus on historically constituted workplace dynamics and relations of domination and subordination, and the social reproduction of workers (see Jonas Citation1996; Taylor et al. Citation2015). This latter element is particularly pertinent to any analysis of the highly feminized labor politics of the clothing industry (Werner Citation2016; Mezzadri Citation2017). In the following section, we examine the ways in which the social relations of postsocialist labor regimes in the Moldovan clothing sector, and their primary characteristics of poverty wages and workplace intensification, have arisen from the intersection of Soviet-era legacies and the requirements of lead firms in GPNs. Workplace and local labor regimes are also formulated in the context of state attempts to (de-)regulate labor markets and working conditions. We argue that the combination of forces that structure labor regimes structurally constrain the reach of the EU’s FTA labor provisions.

European Economic Integration and Labor Regimes in the Moldovan Clothing Sector

In this section we focus on the competitive forces and interfirm relations in the clothing production network in Moldova, and the labor regimes and factory politics that they shape. We do this to highlight the mismatch between the international labor standards framework of the EU FTA’s model of labor governance and the actually existing production politics in the sector. The first subsection examines lead and supplier firm relations and market dynamics as key drivers of working conditions. The following three subsections examine the impact of these production network pressures on workplace labor regimes, mediated by the national political economy and legacies of Soviet-era practices; this is followed by two subsections that discuss the local and national regulatory contexts established in .

Lead and Supplier Firm Relations and Market Dynamics

The Moldovan clothing industry has become deeply integrated into EU production networks as a result of outward processing operations by EU lead firms enabled by tariff liberalization () and the end of quota-constrained trade globally in 2005. Clothing exports to the European Union have expanded rapidly as contracting relations have deepened with Moldovan-based suppliers (). Seventy-eight percent of Moldovan clothing production is exported, of which 92 percent comprises re-exports (Mattila, Gheorghita, and Madan Citation2016), with a high level of reliance on cut–make–trim in outward processing trade (OPT) arrangements. OPT involves fabric and, in some circumstances, trim being provided by EU lead firms directly to Moldovan factories for sewing and re-export to EU markets (see Pellegrin Citation2001; Begg, Pickles, and Smith Citation2003). This production system has built on the established industrial infrastructure of the former USSR. SOEs were privatized during the 1990s, and a landscape of new enterprises, some domestically owned, some with foreign investment, emerged from the early 1990s. Trade liberalization has provided an opportunity for EU firms, especially Italian clothing manufacturers and UK brand and retail buyers, to expand production into a new lower-cost territory as production costs escalated in other East European new member states (Plank and Staritz Citation2015). Employment in the sector accounts for 19 percent of total manufacturing employment, with 14,400 employees in 2015. Around 90 percent of employees in the industry in Moldova are women, an issue we return to later in our consideration of the local labor regime.Footnote11

Figure 2. Clothing exports from Moldova to the European Union, 2000–2016.

Source: Elaborated from Eurostat Comext database.

The form of production network integration into the EU clothing market, and its implications for working conditions in the sector, are shaped by a number of key factors. First, the EU clothing import sector has consistently witnessed declining import prices; falling by 20 percent between 2000 and 2015.Footnote12 Second, Moldovan clothing firms are primarily integrated in to two main EU markets with somewhat distinct forms of interfirm governance. Italy accounted for 46 percent of total EU28 clothing imports from Moldova in 2015, and the United Kingdom accounted for 31 percent. In the Italian context, lead firms are primarily foreign investors and manufacturers who supply a fragmented yet consolidating retail market in Italy in which competition is becoming more intense—a trend dating back to the 1990s (Dunford Citation2006; Sellar Citation2009). Italian foreign investment in Eastern Europe was one of the key strategies pursued in the attempt to remain competitive as Italian manufacturing collapsed (Dunford et al. Citation2013). Italian-owned firms operating in Moldova thus represent a smaller-scale form of what Merk (Citation2014) has called tier 1 manufacturers, providing full-package services and direct supply to Italian brands and retailers. For UK markets, lead firms are primarily branded manufacturers and high street retailers, reflecting their increasing dominance of the retail market (Gibbon Citation2002), which do not engage in foreign investment and rely more on arm’s-length contracting with suppliers.

Despite these specificities of export markets and lead-firm relations, a common feature of contracting relations experienced by factory managers and owners was pressure on contract prices, which impacted consistently on workplace labor regimes. This reflects asymmetric power relations between lead firms and suppliers, although for lower-end mass market manufacturers, contract pressures were highest and profitability tended to be lowest. This is corroborated by interviews with Moldovan managers across different types of firms who stated that “contract price squeezing is constant, making it very difficult to increase wages” (M24); “[c]lients always want lower prices. We don’t have any direct negotiation over contract prices with the buyer. This is done by the Italian company that sells the product to the buyer. It is the Italian partner that negotiates the contract” (M31); and “prices are low and it is very difficult to keep going” (M26; M10). The price pressure that clothing firms are under is reflected in the low profitability of enterprises. Under half (47 percent) of firms in the sector officially register a profit.Footnote13

A second dimension experienced by supplier firms involved the widespread phenomenon of proximate sourcing and rapid turnaround times. This is in the context of the turn toward fast fashion across the European Union (Tokatli Citation2008; Rossi Citation2013) and the utilization of neighboring countries to secure rapid replenishment stock (Pickles and Smith Citation2016). As one respondent stated, “Delivery times are shorter because we have to compete with China and we can’t compete on price. Our advantage is that during the process we can change model[s] on the production line and produce small batches” (M31). Production line flexibility is key to this model (see Rossi Citation2013), and has significant impacts on the labor regime requiring low wages and production line flexibility (see “Wage Relations and Outward Processing Production” below).

In the following sections we highlight the role of these commercial and contract pressures enabled by trade liberalization in shaping labor regimes in Moldova and its mismatch with the EU’s labor provisions. We also show how the embedded social relations of industrial work constituted in the Soviet era influence current labor regimes. We begin with a consideration of workplace labor regimes involving wage relations, norm setting, and work intensification, before turning to the local and national regulatory dimensions of the labor regimes (). We then highlight how workplace labor regime characteristics result from interfirm control in clothing production networks as the industry has become increasingly integrated into pan-European contracting networks. Together these forces explain how the labor provisions in the EU trade agreement are insufficient to regulate extant working conditions.

Wage Relations and Outward Processing Production

Turning to the workplace labor regime (), we first examine wage relations in the outward processing export sector. Integration into the EU export market has been predicated on very low labor costs in comparison with other EU neighboring economies (), alongside the ability of suppliers to respond rapidly to buyer demands (M24; M31). Indeed, Moldovan state agencies market the country as a cheap investment opportunity on the border of the European Union (Moldovan Investment and Export Promotion Organisation Citation2016). However, the EU FTA’s focus on ILO core labor standards does not consider the issue of the living wage and social reproduction that is so fundamental to employment conditions in clothing production networks. In 2015, average net monthly wages were €148, 88 percent of average net wages in manufacturing.Footnote14 The national minimum wage in 2016 was €98,Footnote15 the lowest in Europe. Average wages in the clothing sector are insufficient to meet the basic subsistence requirements for a family of four, which in 2016 was €324.Footnote16 Workplace labor regimes are therefore predicated on wage relations that fail to ensure social reproduction. The minimum wage is often used in clothing factories as the basis for the establishment of the monthly payment norm, with bonuses paid when piece rate norms are met and used to achieve higher take-home pay than the core minimum wage. But with the minimum wage set at such a low level, poverty wages are the result (Clean Clothes Campaign Citation2014, Citation2017).

Table 2 Cost of Labor in EU Neighboring Countries

Poverty wages in the Moldovan clothing industry reflect two dominant factors. First, as discussed in “Lead and Supplier Firm Relations and Market Dynamics,” supplier factory managers are under significant price contract pressure from EU lead firms, since they themselves operate within increasingly competitive and consolidating consumer markets. The primary response in seeking to retain contracts with EU buyers is that of maintaining low wage levels.Footnote17 Second, the national bargaining process for minimum wage setting limits wage growth given the power that a range of employers’ associations, including the National Confederation of Employer’s and the American Chamber of Commerce,Footnote18 wield in constraining wage increases (M8; M34; M36). As one national trade union representative stated, “We have tried to force [through national tri-partite negotiating mechanisms] an increase in the minimum wage but no-one wants to listen” (M36). National and international employers’ organizations thus form part of the spatial networks of labor governance that work to form the poverty pay labor regime of export production.

However, poverty wages are combined with the need for production line flexibility to meet the changing demands of buyers, tight delivery times, and flexible order sizes (M24). The extensive and regular use of overtime is an important element in this context (M36; M41). Overtime is regularly required because factories are waiting for the late arrival of fabric or trim in order to meet orders under the outward processing system (M36). However, overtime was also a site of contestation and ambiguity. On the one hand, non- or inadequate payment of overtime wages is the key issue identified in factory-level inspections in the Moldovan clothing sector (M40).Footnote19 It has also been identified by other key informants as the basis for instances of forced labor when clothing workers have been locked in factories to finish orders (M36). On the other hand, workers highlighted the role that overtime plays in allowing them to improve salary payments to a more sustainable level to try to ensure household social reproduction (M41).

Within the context of supply chain pressures to keep costs and wages low, informal payment practices in the form of envelope wages have become prevalent (M17; M36). Envelope wages involve the payment of the minimum wage as the official wage and an envelope payment of the actual salary above the minimum wage level to avoid tax and insurance (see Williams Citation2008), but this practice does not provide the basis for a living wage (Clean Clothes Campaign Citation2014, Citation2017). Envelope wages are an important part of the Moldovan informal economy in the context of weakened state oversight due to reform and partial disinvestment in the State Labour Inspectorate (M1; M40). There also appears to be worker complicity in informal wage payments: “workers accept ‘envelope salaries’ because the salaries are very small [already], and they are aware that they will receive very low pensions. So they are happy to take salary payments without costs of social insurance reducing them [there is no reduction of 23 percent health and tax costs from the salary]. … This is [also] one of the reasons why managers do not want trade unions” (M36). It is estimated that at least 75 percent of employees in the textiles, clothing, and footwear sectors receive envelope payments (M36).

In summary, the system of outward processing export production establishes a set of wage relations—poverty pay, expansive use of overtime, and informalization of wage payments—that is not adequately regulated via the ILO core labor standards framework at the heart of the EU’s FTA’s labor provisions.Footnote20 Trade liberalization has deepened clothing contracting in Moldova on the basis of informal and poverty wages, but in the context of weakened capacity for trade union bargaining and limited trade union coverage across the sector (see “Worker Representation and the Decline of Independent Trade Unions”), the core labor standards framework does little to ameliorate or eradicate these wage dynamics.

Wage-Setting Norms and Work Intensification

Low wages are tied to a further set of workplace social relations that, like poverty pay, are difficult to regulate via the EU’s labor provisions. These involve wage-setting norms that seek to intensify the labor process, driven by the contracting requirements of lead firms, on the one hand, and the legacies of Soviet-era practices, on the other. They establish the basis on which poverty pay is constituted. Wage-setting norms involve managers seeking to achieve productivity enhancements to meet the exacting requirements of EU buyers, resulting in the intensification of the labor process (see Morrison and Croucher Citation2010; Morrison, Croucher, and Cretu Citation2012). These norms draw upon Soviet-era practices of intensification and individualization of incentives via piece rate norms and bonus payments (Burawoy Citation1985; Clarke Citation1993; Morrison, Croucher, and Cretu Citation2012). Piece rate payment systems are prevalent in the clothing sector generally (Anner Citation2015b), but Moldova was particularly attractive to Italian investors and lead-firm buyers, since it meant that as trade liberalization occurred, they could circumvent the legal limits on the use of piece rates in Italy (M10).

A variety of wage-setting techniques are used to extract greater surplus through the intensification of the labor process. These range from the use of bonus systems on top of the minimum wage to more standard piece rate pay systems. For example, in one major former SOE, the managing director explained how a piece rate system—in conjunction with production-line worker output quotas—was used to enhance productivity: “If a worker wants to earn more money their quota will be increased. If they want to earn more they need to be more efficient” (M24). She went on: “we use piece rates to incentivize higher production to meet the company’s lack of capacity as a result of not having enough workers” (M24). Piece rate payments are used to enhance worker productivity and to attempt, in the view of this manager, to deal with insufficient worker discipline in the context of the production requirements of EU export contracting: “the employees are not productive enough because of the prevalence of a Soviet-type culture. … There is no discipline anymore” (M24).

In the Soviet system the “main managerial tools were the individualized piece-rate, a large array of bonuses, and selective use of welfare benefits,” all of which were “intended to reproduce the ‘labor collective’” (Croucher and Morrison Citation2012, 584; see also Clarke Citation1993). Burawoy (Citation1985) called the resulting production politics bureaucratic despotism, in which exacting production norms combined with an intensification of the labor process and resulted in domination by the workplace foreman, enterprise trade union, and the Communist Party (Clarke Citation1993; Morrison Citation2008). Piece rates and the “dictatorship of the norm” (Burawoy Citation1985, 168) were the primary mechanisms through which the bureaucratic planned economies controlled workers’ plan fulfillment. The result was shop floor informal bargaining over pay norms and bonuses (Morrison Citation2008).

The current utilization of piece rates and bonuses builds upon these Soviet-era practices. For example, in one firm that produces for both its own network of retail outlets in Moldova and for export orders under OPT arrangements, wage levels were relatively high (but still below a level required for basic social reproduction) with an average monthly gross salary for a seamstress of between €254 and €300. These pay levels are achieved via the use of a dual wage-setting mechanism involving payment by the operation norm for domestic market production and piece rate payment for OPT export production. For the enterprise, the combination of markets for its production is critical, since domestic-oriented production is insufficient to sustain the enterprise. Reliance on OPT is paramount, constraining any alternative market-driven upgrading, but at the same time is where contract squeezing is most significant. The managing director highlighted how both of these systems of norm-setting were adopted from a larger local SOE because “a lot of our workers came from there and the person doing the analysis of norm setting came from that firm” (M29). This is a phenomenon found in other factory interviews (e.g., M39).Footnote21

While being transformed to the market conditions of OPT production, the continued utilization of piece rates and bonus incentive systems indicate how managers have had to intensify the labor process to meet the exacting contracting requirements of EU lead firms. OPT has dramatically compounded these pressures in the workplace labor regime, with exacting requirements and the squeezing of contracts by lead firms, tightening labor markets, and out-migration. This has also established a paradox because while manager’s reliance on workers has increased (see Morrison Citation2008), if workers are not satisfied with piece rate norms or overly intensified working environments, in the context of tight labor markets and labor shortages, they can move to another factory, if they have the sufficient skill set, or indeed may leave for more potentially lucrative pay abroad. We return to the paradoxical impact of these tightening labor markets in “Tight Labor Markets in the Local Labor Regime.” However, like the issue of poverty pay, the use of piece rates that underpins low wage levels and workplace intensification are also not captured by the ILO frameworks used in the EU’s trade agreement labor provisions. Consequently, the capacity of these labor provisions to attend to the primary structural causes of poor working conditions is severely limited (cf. Hauf Citation2015).

Worker Representation and the Decline of Independent Trade Unions

A third element of the workplace labor regime concerns the role of trade unions in regulating workplace conditions (). Despite Moldovan constitutional guarantees and ILO frameworks on freedom of association being at the heart of the EU’s labor provisions, the representation of clothing sector workers is limited and declining.Footnote22 Only nine clothing enterprises, all of which were former SOEs, had a recognized trade union (M8; M36).Footnote23 In newly established private enterprises, there is significant pressure from factory management not to allow trade union representation: “in one case someone tried to organize a union two years ago. The owner heard about this and the person was fired but they found another reason for the dismissal” (M36). Furthermore, managers argued that workers did not want to establish factory unions because of the additional costs to them of membership and a perception that the benefits did not warrant the costs (M26; M31).Footnote24

Trade union presence in the former SOEs does allow workers to avoid some of the worst excesses of exploitation. There are, however, significant limits to the ability of enterprise unions to fully represent clothing workers and deal with the issues of poverty wages and the informalization of pay. Unions have only survived in the former SOEs because of foreign owners’ “wishes to comply with the law and the requirements of inspectors dispatched by ethically branded clients” (Morrison and Croucher Citation2010, 234), especially corporate codes of conduct. Establishment of union representation in new firms is a recognized problem. The International Trade Union Confederation has noted that “The creation of new unions remains a problem due to the employers’ resistance. Collective agreements are mainly signed at enterprises having a long history of collective bargaining [i.e., former SOEs]. Legislative enforcement remains weak. Neither labor inspectorates nor prosecutors’ offices have been effective in monitoring and enforcing labor standards, especially the right to organize.”Footnote25 The proportion of workers covered by collective agreements is 12–13 percent of total employment and 17 percent of employees but “collective agreements are barely respected at the level of industrial units or at the sector level” (Vasilescu Citation2016, 6).

Even where enterprise-level trade unions are present, the legacies of the Soviet system remain. In the Soviet Union, trade unions were a fundamental part of the labor collective and represented all workers in the enterprise, including management (Clarke Citation1993; Clarke and Fairbrother Citation1993; Morrison and Croucher Citation2010). This reflected the contradictory nature of the union in centrally planned economies, which at the “enterprise level … was an instrument of the enterprise administration in its attempt to subordinate the labor force to its over-riding goal of achieving plan targets” (Clarke and Fairbrother Citation1993, 93), but this role was supposed to be subordinated to the overarching authority of the working class via the Communist Party state apparatus.

In the post-Soviet period, the continuing relationship between trade unions and enterprise management has meant that while unions are notionally an independent mechanism to represent the interests of workers in the few former SOEs that have them, the legacies of the everyday social foundations of worker representation has provided an opportunity for the capture of some enterprise unions by management (M24; M33). In addition, the Soviet-era focus on trade unions as a welfare function for the reproduction of the labor collective, rather than an independent voice representing the interests of workers, has been retained (M26; M31). In this sense, while the labor provisions in the EU trade agreement provide a framework for legally guaranteeing freedom of association, the realities of production politics embedded in the legacies of the Soviet era, and the desire of managers not to extend trade union membership, significantly constrain these legal formulations, without an effective mechanism to deal with this mismatch.

Tight Labor Markets in the Local Labor Regime

Turning now to the local labor regime in the Moldovan clothing industry, a paradox exists in the coexistence of tight labor markets and the prevalence of low wages. Labor supply conditions in the local labor regime () involving tight labor markets have arisen from the expanding demand by lead firms for clothing exports, on the one hand, and the loss of workers to out-migration, on the other. With 25 percent of the working age population in 2015 constituting migrant workers,Footnote26 the economy has become highly reliant on remittances, accounting for 22 percent of gross domestic product in 2014 (Vasilescu Citation2016). However, Moldovan clothing workers have been unable to leverage the structural power that tight labor markets provide (Silver Citation2003; Anner Citation2015a).Footnote27 Workers have potential labor market power in the context of very tight labor markets, but they have been unable to organize and protest in a meaningful way at firm level or nationally in part due to the limited role of trade unions in the industry. Their local potential structural power resulting from labor shortages and tight labor markets is actually undermined by the ability of buyers to seek out alternative sourcing companies in other locations. Workers are consequently impacted by labor market control regimes in the form of very low wages, intensification of the labor process, and a lack of/weak representation despite having potential labor market power given the out-migration and shortage of workers in the industry. We therefore need to look at the weakening of trade unions and the intensification of the labor process in the context of international contracting to explain this. Enterprise managers have been trying to balance demands for labor intensification and productivity increases resulting from the tightening of lead-firm contracts with the relative scarcity of labor and tight labor markets (Centre for Sociological, Political and Psychological Analysis and Investigations CIVIS Citation2008; National Confederation of Employers of the Republic of Moldova Citation2013).

Tight labor markets in the clothing sector were a particular problem in the capital city of Chişinău (the main clothing production center), leading many enterprises to subsidize low wages via housing and transportation supplements, the former being a practice that was also found in the Soviet system. For example, one large former SOE provided accommodation for almost two hundred workers in Chişinău and rent subsidies two to three times lower than average commercial rent levels in the city (M24). Despite this, the managing director suggested that the lack of workers is the main problem for the enterprise, which had a 10 percent vacancy rate, and for the industry in general (M24). This experience was replicated across many enterprises in the sector (e.g., M26), demonstrating that exit from the industry and the country has been the primary form of resistance of workers to poor working conditions.

Out-migration compounds a further labor supply constraint resulting from absenteeism, since workers work on own-farm production in peak growing seasons, seeking to supplement low wages with alternative means of subsistence (M27) (see Pickles Citation2002). During the summer, there is a decrease in the availability of labor because of agricultural work (for self-sufficiency) and also because some people go abroad to work for short periods. However, enterprises need more workers during this period, when winter collections are manufactured (M31; M33). This is a particular issue for the clothing sector, given its reliance on female labor and the preponderance of women involved in domestic food production. The working day in several factories was consequently arranged to accommodate women working on plots of land in the afternoon (M31), compounding the double burden they faced.

A further factor impacting labor shortages is the maternity leave system, which given the numerical dominance of women workers in the clothing sector is critical. Women are entitled to three years of paid leave and a further three years of unpaid leave during which point a job remains guaranteed. There is significant pressure from employers to reduce this maternity leave system (M36; M38), who see it as a major constraint on labor flexibility.

These labor market and labor supply dynamics in the local labor regime highlight the contradictions at the heart of the clothing sector in Moldova. Factory managers with burgeoning export orders with tight contracts have to mediate scare labor supply. However, the FTA’s labor provisions do not account for these wider labor market dynamics in any systematic way. Rather they focus more on labor representation and eradication of extreme forms of exploitation (e.g., child and forced labor) and consequently are unable to address the structural dynamics causing poor working conditions.

The State and the Regulation of the National Labor Regime

A final dimension of the labor regime governing employment relations in the Moldovan clothing sector relates to the national state’s regulatory framework (). It is at this scale that one might expect the greatest purchase of the EU’s utilization of the ILO core labor standards framework to ameliorate the worst consequences of lead-firm pressure, given that states are signatories to these conventions. Three dimensions are important here. First, the Moldovan state has seen its power to regulate via minimum wage setting eroded under pressure from employers’ associations, committed to a liberalization of the labor market (M8; M19). For example, the National Confederation of Employers of the Republic of Moldova (2015) has lobbied for liberalization proposals around hiring and firing, and there is pressure from different employers’ associations to amend the labor code, aiming to reduce workers’ rights (e.g., maternity leave, sick leave, and unpaid leave) (M34; M36).

Second, the State Labour Inspectorate has been weakened, undermining the implementation of legal obligations arising from international labor standards. A law on state control of businesses was passed in 2012 and limited the ability of the labor inspectorate to make unannounced and unplanned factory inspections (Barbu et al. Citation2017; Smith et al. Citation2017).Footnote28 Despite an ILO ruling that this contravened Convention 81 on labor inspection, no significant improvement has occurred. The result has been an increase in the number of complaints and accidents, a reduction in the capacity to detect undeclared work (ILO Citation2015), and continued contravention of Convention 81 (M34). Further government reform proposals (e.g., to separate health and safety from employment relations inspections) are likely to reduce further the ability to conduct effective inspection (M34).Footnote29

Third, the wider Association Agreement contains provisions for the implementation of EU Directives on employment and occupational health and safety (OHS). The new requirements relating to OHS are being implemented with potentially significant positive outcomes for workers (e.g., annual worker health checks) but with additional employer costs. This is compounded by a wider dynamic of labor market deregulation (a key focus of the main employers’ associations) and the emergence of a new market opportunity for EU third-party providers of OHS checks of Moldovan workers. Ironically, the impact may be a squeezing of wages, since employers have to cover these additional costs (up to an extra one month salary per employee per year in one case) (M29). This squeezing could be avoided by reducing the profit margins of firms and (potentially) increasing the minimum wage, but the value chain space to do this is very limited as major clients are exacting in their contract price negotiations.

Conclusion

We have argued that assessing the scope for labor provisions in a trade agreement to regulate working conditions in the Moldovan clothing industry requires an understanding of labor regimes and production network dynamics. We have highlighted how these regimes are shaped by two main processes. The first relates to a set of processes concerning power relations between management and owners in supplier and lead firms. The second concerns the transformation of the legacies of Soviet-era labor regimes, in particular the social relations of workplace wage and norm-setting, the uneven landscape of trade union organization, and the gendering of social reproduction and tight labor markets. Neither of these processes nor the primary issue of poverty wages and informal pay to which they give rise are adequately captured in the EU’s labor provisions’ framework to govern the employment consequences of trade liberalization. The focus on ILO core labor standards, at the heart of the EU’s approach, are wedded to a social dialogue model of employment relations and do not address the critical role of interfirm power relations and structural drivers of workplace labor regimes. Nor are proposed reforms (European Commission Citation2017) likely to overcome these structural contradictions.Footnote30 As such, there are strong parallels here with the limits of other ILO core labor standards and decent work motivated programs such as Better Factories/Better Work in Cambodia (Arnold and Shih Citation2010) and elsewhere (Hauf Citation2015). As Hauf (ibid., 150) has argued, ILO decent work proclaims the right to universal standards “without challenging the structural mechanisms causing indecent working conditions in the first place.” Our argument has been that integration into export production networks and the role of lead-firm contracting pressure, when conjoined with the legacies of Soviet-era labor relations, work to undermine the declarations of decent work in recent EU trade policy. In Moldova, freedom of association is guaranteed in law, and child labor, forced labor, discrimination, and unequal remuneration are outlawed.Footnote31 But the erosion of freedom of association as a result of the decline of trade union membership and very uneven coverage of workers means that unions do not provide the bulwark against worsening labor standards. The consequence is that neither the earlier conditionalities in the EU’s Generalized Scheme of Preferences plus (GSP+) policy framework or the relatively weak civil society monitoring mechanisms of the Association Agreement provide a robust enough mechanism for meaningful labor regulation. Without this framework being attentive to the forms of unequal power relations that integrate supplier factories into EU production networks, and an understanding of their articulation with labor regime dynamics, trade policy will be unable to deal with the causes of poor working conditions that result from trade and economic integration.

In making this argument, this article has contributed to debates over the fate of labor in GPNs in two main ways. First, we have developed an analytical framework of nested scales of historically sedimented labor regimes and their connections to lead-firm supplier power relations and state regulation. We have argued that the Soviet labor regime has been adapted to intensify working conditions as firms became integrated into EU production networks and current national state frameworks seek to liberalize labor markets to the detriment of workers. When combined with an erosion of trade union power, we therefore find significant structural limitations to worker agency in GPNs. This framing illustrates the analytical power of integrating labor process theory into analysis of GPN dynamics (see Taylor et al. Citation2015), and we have sought to extend that debate through the formulation of conceptualization of the nested scales of labor regime regulation. Second, we have highlighted how state-driven forms of global labor governance deployed through FTA labor provisions are limited in ameliorating the worst excesses of labor exploitation in GPNs. GPNs are not only systems of market integration, interfirm coordination, and value adding activity, but they are constructed through the sociopolitical contexts in which they are situated (see Levy Citation2008; Pickles and Smith Citation2016). This reiterates the contradictory role of the state in international trade policy, which seeks to balance its accumulation and legitimation functions by constructing new spaces for market exchange while being seen to regulate work via international labor standards without addressing the structural basis for poor working conditions: a contradiction that also shapes how GPNs are able to expand and exploit in macroregional economic geographies.

Acknowledgments

This article arises from research undertaken as part of a UK Economic and Social Research Council-funded project entitled “Working Beyond the Border: European Union Trade Agreements and Labour Standards” (award number: ES/M009343/1). We are very grateful to Irina Tribusean for providing research and translation assistance in Moldova. A previous version of the article was presented at the workshop on Labour Provisions, Trade Agreements and Global Value Chains held at Queen Mary University of London, June 2017, and as an invited plenary lecture given by Adrian Smith at the sessions on “Advancing Global Production Networks Research” at the Annual International Conference of the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), London, August 2017. We are grateful to workshop and conference participants, and to the editor and reviewers of Economic Geography for their thorough and helpful comments on an earlier version of the article.

Notes

1 This article uses GPN terminology while recognizing the parallels and differences with global value chain approaches. We do not have space to elaborate these differences here (but see Taylor et al. Citation2015; Havice and Campling Citation2017). Rather our focus is on the form of power relations between lead firms and suppliers in clothing GPNs and a conceptualization of the links between GPNs and labor regimes.

2 Article 365, EU–Moldova Association Agreement.

3 Access was negotiated in this way given the widespread suspicion of foreign researchers among firm managers in the industry due to the commercial pressures they are under and the working conditions found (M8; M36).

4 It is a process that has its parallels with the internal deepening of the single market, which some have seen as involving the “driving down [of] wages and conditions” of work (Cumbers et al. Citation2016, 94).

5 Article 365, EU-Moldova Association Agreement.

6 Article 367, EU-Moldova Association Agreement.

7 See Smith et al. (Citation2017) and Harrison et al. (Citationforthcoming) for an assessment of these institutional mechanisms in the TSD chapter of the FTAs.

8 This is the labor control regime “within the labour process” (Pattenden Citation2016, 1813).

9 See also Taylor et al. (Citation2015) for the distinction between workplace and local labor regimes.

10 For the last five years, retail revenue growth in clothing has been lower than in other major consumer goods sectors (elaborated from query on https://www.statista.com database).

11 Elaborated from National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova: http://statbank.statistica.md.

12 Elaborated from Eurostat Comext database: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/newxtweb/. Data were deflated to real terms using Eurostat’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices. Data are for EU15—the pre-2004 enlargement (i.e., core Western European) member states.

13 Elaborated from National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova: http://statbank.statistica.md.

14 Elaborated from National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova: http://www.statistica.md/category.php?l=en&idc=107&. A Clean Clothes Campaign report in 2014 identified average take home net wages as €123. Data in show labor costs at €180 per month, reflecting the difference between cost and actual wage payments. Currency conversions based on January 20, 2017, using http://xe.com (€1 = 23.34MDL).

15 Government of Moldova, Decision No.165, March 9, 2010, amended for 2016 on April 20, 2016: http://lex.justice.md/md/333943/.

16 Elaborated from National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova, http://www.statistica.md/category.php?l=en&idc=445&#idc=288&.

17 See ILO (Citation2017) for a parallel argument in a global context.

18 The American Chamber of Commerce has over one hundred members, many of whom are leading international corporations.

19 The labor code establishes that weekend work is paid at double-pay and that additional working time during the standard working week is paid at a rate of 50 percent more for the first two hours and 100 percent for the following two hours. Contravention of these norms was highlighted in labor inspection reports for the sector (M40). However, the establishment of what the working day is defined as (i.e., the duration of working time, the length of the working week [number of days], the number of shifts, the time for starting/ending the working day, length of breaks, and the alternation of working and nonworking time) all take place at factory level.

20 See Arnold (Citation2013) for a parallel analysis of the mismatch between declining real wages in Cambodia and the tenets of the Better Work Program and Hauf (Citation2015, 149) who argued that this program’s focus on the legal minimum wage “is not sufficient to measure decent work as the minimum wage … is still below subsistence level.”

21 Basic salary norms are underpinned by bonus incentives paid to employees for the quality and complexity of work undertaken. This reduces the control that workers have over their ability to “protect piece rate work earning through familiarity with the work” (Croucher and Morrison Citation2012, 595). Workers’ ability to maximize piece rate income is undermined as they are deployed flexibly across different tasks and machines depending on the requirements of orders from EU buyers.

22 Trade union density has fallen from just over 51 percent in 2010 to 28 percent in 2013 (ILO STAT data: http://www.ilo.org/ilostat); 2010 figures are based on Confederation of Trade Union data and 2013 figures are based on Labour Force Survey data).

23 There are 377 registered enterprises in the clothing sector, which is likely to be larger in number once unregistered companies and workshops are included.

24 This is despite the fact that the cost of trade union membership was only 1 percent of salary (M36). If the costs of membership are the core reason, the primary underlying factor was the low wage levels in the sector in which sustaining a livelihood was difficult.

26 Elaborated from National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova: http://statbank.statistica.md. This includes those working or looking for work abroad.

27 [Olin Wright (Citation2000) established the distinction between two forms of power—associational (i.e., power achieved via organizing and representation of workers) and structural (i.e., power resulting from position in the labor market, e.g., tight labor markets [what Silver (Citation2003) called workplace structural power] or position in a key industry [what Silver called marketplace structural power]). Labor shortages would lead us to expect an increase in the price of labor. This does not happen, however, because migrants’ remittances have become an important part of household income; the female workforce is less mobile, since they are the main family welfare providers; and because trade unions are very weak, workers’ collective action is limited. Therefore, the structural power of the workforce through tight labor markets is almost nonexistent.

28 Government of Moldova, Law No. 131, June 8, 2012.

29 An initial set of proposals for revision were developed that involved the closing of the State Labour Inspectorate. “This was pushed by the American Chamber of Commerce” and was focused on the liberalization of the labor market and reducing regulatory controls on companies (M34). Following this proposal, the trade unions, the EU delegation to Moldova, and the ILO office in the country lobbied government, and a revised set of proposals appeared (M34).

30 See also Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (Citation2017) for a parallel argument over the limited reach of ILO core labor standards. This thinking is feeding into considerations of alternative model social chapters in EU FTAs, which the Socialists and Democrats Group in the European Parliament are attempting to pursue in light of the European Commission’s (2017) launch of a consideration of alternative models.

31 Although there have been instances of forced labor in clothing enterprises (M41).

References

- Alston, P. 2004. Core labour standards and the transformation of the international labour rights regime. European Journal of International Law 15 (3): 457–521. doi:10.1093/ejil/15.3.457.

- Anner, M. 2015a. Labor control regimes and worker resistance in global supply chains. Labor History 56 (3): 292–307. doi:10.1080/0023656X.2015.1042771.

- ———. 2015b. Social downgrading and worker resistance in apparel global value chains. In Putting labour in its place, ed. K. Newsome, P. Taylor, J. Bair, and A. Rainnie, 152–70. London: Palgrave.

- Arnold, D. 2013. Better work or ‘ethical fix’? Global Labour Column 155 (November). http://www.global-labour-university.org/fileadmin/GLU_Column/papers/no_155_Arnold.pdf.

- Arnold, D., and Hess, M. 2017. Governmentalizing Gramsci: Topologies of power and passive revolution in Cambodia’s garment production network. Environment and Planning A 49 (10): 2183–202. doi:10.1177/0308518X17725074.

- Arnold, D., and Shih, T. H. 2010. A fair model of globalization? Journal of Contemporary Asia 40 (3): 401–24. doi:10.1080/00472331003798376.

- Baglioni, E. 2017. Labour control and the labour question in global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbx013.

- Barbu, M., Smith, A., Harrison, J., Richardson, B., and Campling, L. 2017 A note on the state labour inspectorate in the Republic of Moldova. Unpublished technical note produced for EU Domestic Advisory Group members, available from the authors.

- Begg, R., Pickles, J., and Smith, A. 2003. Cutting it: European integration, trade regimes and the reconfiguration of East-Central European apparel production. Environment and Planning A 35 (12): 2191–207. doi:10.1068/a35314.

- Burawoy, M. 1985. The politics of production. London: Verso.

- Campling, L. 2016. Trade politics and the global production of canned tuna. Marine Policy 69: 220–28. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.02.006.

- Campling, L., Harrison, J., Richardson, B., and Smith, A. 2016. Can labour provisions work beyond the border? Evaluating the effects of EU free trade agreements. International Labour Review 155 (3): 357–82. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2015.00037.x.

- Centre for Sociological, Political and Psychological Analysis and Investigations CIVIS. 2008. Labour market in Moldova–2008. Chișinău, Moldova: CAISPP CIVIS.

- Clarke, S. 1993. The contradictions of ‘state socialism.’ In What about the workers? ed. S. Clarke, P. Fairbrother, M. Burawoy, and P. Krotov, 5–29. London: Verso.

- Clarke, S., and Fairbrother, P. 1993. Trade unions and the working class. In What about the workers? ed. S. Clarke, P. Fairbrother, M. Burawoy, and P. Krotov, 91–120. London: Verso.

- Clean Clothes Campaign. 2014. Stitched up: Poverty Wages for Garment Workers in Eastern Europe and Turkey. https://cleanclothes.org/livingwage/stitched-up.

- ———. 2017. Made in Europe: The ugly truth. https://cleanclothes.org/livingwage/europe.

- Coe, N. 2015. Labour and global production networks. In Putting labour in its place, ed. K. Newsome, P. Taylor, J. Bair, and A. Rainnie, 171–92. London: Palgrave.

- Coe, N., and Hess, M. 2013. Global production networks, labour and development. Geoforum 44: 4–9. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.08.003.

- Coe, N., and Yeung, H. W.-C. 2016. Global production networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coe, N., Dicken, P., and Hess, M. 2008. Global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography 8 (3): 271–95. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn002.

- Croucher, R., and Morrison, C. 2012. Management, worker responses, and an enterprise trade union in transition. Industrial Relations 51 (2): 583–603. doi:10.1111/j.1468-232X.2012.00691.x.

- Cumbers, A., Featherstone, D., MacKinnon, D., Ince, A., and Strauss, K. 2016. Intervening in globalization. Journal of Economic Geography 16 (1): 93–108. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu039.

- Cumbers, A., Nativel, C., and Routledge, P. 2008. Labour agency and union positionalities in global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography 8 (3): 369–87. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn008.

- Dunford, M. 2006. Industrial districts, magic circles, and the restructuring of the Italian textiles and clothing chain. Economic Geography 82 (1): 27–59. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2006.tb00287.x.

- Dunford, M., Liu, W., Dunford, M., Barbu, M., and Dunford, R. 2013. Globalisation, cost competitiveness and international trade. European Urban and Regional Studies 23 (2): 111–35. doi:10.1177/0969776413498763.

- Elias, J. 2007. Women workers and labour standards: The problem of ‘human rights’. Review of International Studies 33 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1017/S0260210507007292.

- Emerson, M., and Cenuşa, D. 2016. Deepening EU-Moldovan relations. London: Rowman and Littlefield.

- European Commission. 2015. Civil society’s role in the DCFTAs. Presented at the Eastern Partnership, Civil Society Forum, Georgia, September 25.

- ———. 2017. Non-paper of the commission services: Trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters in EU free trade agreements (FTAs). http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/july/tradoc_155686.pdf.

- Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. 2017. How to make trade benefit workers? http://www.fes-asia.org/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/_DIGITAL_READ_FES_CLS_2017.pdf.

- Gereffi, G. 1994. The organization of buyer-driven global commodity chains. In Commodity chains and global capitalism, ed. G. Gereffi and M. Korzeniewicz, 95–122. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Gibbon, P. 2002. At the cutting edge? Financialisation and UK clothing retailers’ global sourcing patterns and practices. Competition and Change 6 (3): 289–308. doi:10.1080/10245290215045.

- Glassman, J. 2011. The geo-political economy of global production networks. Geography Compass 5 (4): 154–64. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00416.x.

- Harrison, J., Barbu, M., Campling, L., Richardson, B., and Smith, A. Forthcoming. Governing labour standards through free trade agreements: Limits of the European Union’s free trade agreements. Journal of Common Market Studies.

- Havice, E., and Campling, L. 2017. Where chain governance and environmental governance meet. Economic Geography 93 (3): 292–313. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1292848.

- Hauf, F. 2015. The paradoxes of decent work in context. Global Labour Journal 6 (2): 138–55. doi:10.15173/glj.v6i2.2327.

- Horner, R. 2017. Beyond facilitator? Geography Compass 11 (2). doi:10.1111/gec3.12307.

- International Labour Organization. 2013. The social dimensions of free trade agreements. Geneva: ILO.

- ———. 2015. Report of the Committee set up to examine the representation alleging non-observance by the Republic of Moldova of the Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No. 81), Submitted Under Article 24 of the ILO Constitution by the National Confederation of Trade Unions of Moldova (CNSM). GB.323/INS/11/6. Geneva: ILO.

- ———. 2017. Purchasing practices and working conditions in global supply chains. INWORK Issue Brief 10. Geneva: ILO.

- Jonas, A. 1996. Local labour control regimes. Regional Studies 30 (4): 323–38. doi:10.1080/00343409612331349688.

- Kabeer, N. 2004. Globalization, labor standards, and women’s rights: Dilemmas of collective (in)action in an interdependent world. Feminist Economics 10 (1): 3–35. doi:10.1080/1354570042000198227

- Kelly, P. 2002. Spaces of labour control. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 27 (4): 395–411. doi:10.1111/1475-5661.00062.

- Lakhani, T., Kuruvilla, S., and Avgar, A. 2013. From the firm to the network: Global value chains and employment relations theory. British Journal of Industrial Relations 51 (3): 440–72. doi:10.1111/bjir.12015.

- Levy, D. 2008. Political contestation in global production networks. Academy of Management Review 33 (4): 943–63. doi:10.5465/AMR.2008.34422006.

- MacKinnon, D. 2017. Labour branching, redundancy and livelihoods: Towards a more socialised conception of adaptation in evolutionary economic geography. Geoforum 79 (15): 70–80. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.005.

- Mattila, H., Gheorghita, M., and Madan, S. 2016. Recommendations for creating a roadmap for competitive development of Moldovan Fashion Manufacturing Industry. Unpublished document (on file with authors).

- Merk, J. 2014. The rise of tier 1 firms in the global garment industry: Challenges for labour rights advocates. Oxford Development Studies 42 (2): 259–77. doi:10.1080/13600818.2014.908177.

- Mezzadri, A. 2017. The sweatshop regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moldovan Investment and Export Promotion Organisation. 2016. Textile, apparel, footwear and leather goods. http://miepo.md/sites/default/files/reports/TAFL%20sector%20overview.pdf.

- Morrison, C. 2008. A Russian factory enters the market economy. London: Routledge.

- Morrison, C., and Croucher, R. 2010. Moldovan employment relations: “Path dependency”? Employment Relations 32 (3): 227–47. doi:10.1108/01425451011038771.

- Morrison, C., Croucher, R., and Cretu, O. 2012. Legacies, conflict and ‘path dependence’ in the former Soviet Union. British Journal of Industrial Relations 50 (2): 329–51. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2010.00840.x.

- Muszynski, A. 1996. Cheap wage labour. London: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- National Confederation of Employers of the Republic of Moldova. 2013. Key constraints on the business environment in Moldova. Chişinău, Moldova: NCERM.

- ———. 2015. The need for labour law flexibility. Chişinău, Moldova: NCERM.

- Newsome, K., Taylor, P., Bair, J., and Rainnie, A., eds. 2015. Putting labour in its place. London: Palgrave.

- Olin Wright, E. 2000. Working-class power, capitalist-class interests, and class comprise. American Journal of Sociology 105 (4): 957–1002. doi:10.1086/210397.

- Pattenden, J. 2016. Working at the margins of global production networks: Local labour control regimes and rural-based labourers in South India. Third World Quarterly 37 (10): 1809–33. doi:10.1080/01436597.2016.1191939.

- Peck, J. 1996. Work-place. New York: Guilford Press.

- Pellegrin, J. 2001. The political economy of competitiveness in an enlarged Europe. New York: Palgrave.

- Pickles, J. 2002. Gulag Europe? Mass unemployment, new firm creation, and tight labour markets in the Bulgarian apparel industry. In Work, employment and transition, ed. A. Rainnie, A. Smith, and A. Swain, 246–72. London: Routledge.

- Pickles, J., and Smith, A. 2016. Articulations of capital. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.