Abstract

Engaging with different literatures in economic geography, postcolonial urbanism, and planetary urbanization, this article seeks to develop a theoretical understanding of remote urban formations taking shape in India’s countryside. The analysis draws on extensive primary data collected at two study sites in Bihar and West Bengal, which rendered an uncommonly rich data set for such remote areas. We observe emergent urban formations that result from densification, expansion, and amalgamation of built-up environments and a massive shift of employment out of the agricultural sector. At the same time, alternative local economic opportunities are scarce, giving way to significant increases in circular labor migration. We introduce the concept of injected urbanism to denote a form of urbanization that is exogenously generated through remittances, in the absence of significant local agglomeration processes. The infusion of remittances drives local economic restructuring and the emergence of a consumption economy. Injected urbanism spurs local development, but its dependence on economic activity elsewhere raises important questions about its sustainability.

Recent years have witnessed a steady decentering of urban theory, shifting attention away from a relatively small number of dominating (Western) cities that attracted a disproportionate share of attention, driven by growing research on cities of the Global South, and with increasing interest in urbanization processes outside major agglomerations (e.g., Robinson Citation2006; Brenner and Schmid Citation2015; Simone Citation2020). This decentering has been accompanied by increased scrutiny of the portability of northern theory, debates about universalizing versus provincializing theoretical claims, and a fast-growing literature on comparative urbanism (e.g., Nijman Citation2007, Citation2015a; Ward Citation2008; McFarlane and Robinson Citation2012; Sheppard, Leitner, and Maringanti Citation2013; Peck Citation2015).

We join these debates with a study of India’s urbanizing periphery, defined as emergent urban formations in remote, previously agricultural, regions. Our research focus is, in a way, doubly decentered: away from the Global North and far removed from the big cities that today monopolize so much research attention in the Global South. We argue that this focus on the proverbial edges of the urban studies discipline is relevant to some of the theoretical debates at its core.

Moreover, as we will point out, these remote urbanization processes are far from a marginal phenomenon: they represent roughly one-third of India’s overall urban growth (Pradhan Citation2017). In this article, we focus primarily on the changing economic geographies that accompany these urbanization processes. One of the main drivers of this rural–urban transition is the massive shift of employment out of agriculture across large swaths of rural India, a transformation that is estimated to affect the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people (Government of India Citation2018). The empirical part of our research concentrates on two remote regions in India’s Gangetic Plain: in western Bihar and in central West Bengal. We draw from primary data collected during extensive field work in 2019 that rendered a rich and rare data set for these kinds of remote regions.

We engage with three strands of theoretical literature: urban economic geography, postcolonial urbanism, and planetary urbanization. Each offers important vantage points but is limited in its applicability to India’s urbanizing periphery. Our approach is inspired by the notion of engaged pluralism (Barnes and Sheppard Citation2010) and is based on a combination of transduction and frame switching. Transduction refers to a dialectical relationship between theoretical formulation and empirical observation—one that we believe is an essential disposition in all exploratory research (Lefebvre Citation1970; Schmid et al. Citation2018; Van Duijne and Nijman Citation2019). Frame switching involves the deliberate deployment of alternating theoretical perspectives in the interpretation of lesser-studied empirical phenomena (Van Meeteren, Bassens, and Derudder Citation2016).

One of the key arguments we advance concerns the concept of injected urbanism. This refers to urbanization that is exogenously generated, in the absence of significant local agglomeration. We find that these dispersed urbanizing formations are characterized by rapidly declining agricultural sectors but with scarce alternative employment opportunities, leading to large-scale male labor migration. Remittances play a vital part in fueling the restructuring local economies and urbanization processes. Injected urbanism spurs local development, but its dependence on economic activity elsewhere raises important questions about its sustainability.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. First, we provide some important context to India’s urbanizing periphery and the social transformation that is reshaping the country’s vast rural regions. We subsequently discuss the theoretical literatures mentioned above in terms of their relevance and limitations to this study, and we frame key theoretical arguments that guide our research. This is followed by a section on research design and methodology, which leads up to the empirical analysis. The concluding section summarizes important findings and circles back to the implications for urban theory.

Contextualizing India’s Emergent Urban Formations

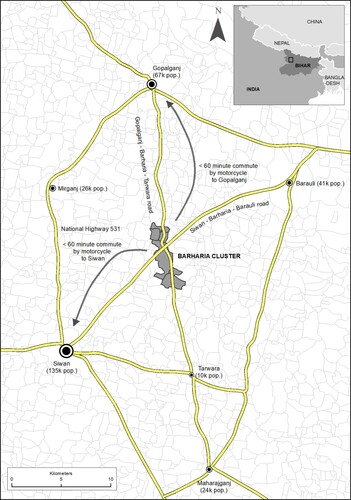

Contrary to popular imaginations about the country’s exploding megacities, India’s official urbanization level is quite low. It is one of the least urbanized countries in the world, with two-thirds of its 1.3 billion people, as reported by the Indian census, currently still living in rural areas. Agriculture still employs, by far, the largest number of people (Government of India Citation2016; World Bank Citation2021). Urban growth rates have actually declined in recent decades, and they have done so despite accelerating economic growth (). As such, India’s experience contradicts conventional theory, which posits positive correlations between economic growth and urban growth (e.g., Henderson Citation2002; World Bank Citation2009; Scott and Storper Citation2015). Interestingly, it also contrasts with reports on many African countries, which point to the opposite pattern: rapid urban growth accompanied by low economic growth, what has been referred to as urbanization without industrialization (e.g., Jedwab and Vollrath Citation2015).

Figure 1. India’s economic growth rates (gross domestic product at constant prices) and urban growth rates.

Source: Government of India (2011); World Bank (Citation2021).

The literature offers several explanations for India’s overall slow growth. Some point to India’s exclusionary cities that fail to accommodate rural–urban migrant families due to a lack of housing and the high cost of living (Kundu Citation2014); others emphasize the lack of labor-intensive urban industries, despite overall impressive economic growth (Nijman Citation2015b). Rural–urban migration accounts for a relatively small share (compared to natural growth) of overall urban growth (Bhagat Citation2012).

Another important contextual trend concerns the increased concentration of India’s urban growth in the lower echelons of the urban system: the countryside is experiencing a major rural-to-urban transition. In recent years, there has been a rapid proliferation of so-called census towns, or CTs, and a growing body of writing about these urbanizing villages (e.g., Chatterjee Murgai, and Rama Citation2015; Guin and Das Citation2015; Denis and Zérah Citation2017; Pradhan Citation2017; Sircar Citation2017; Jain Citation2018; Mehta Citation2018; Mitra and Tripathi Citation2021). CTs are former rural settlements that for the first time meet the threefold Indian census definition of urban: a population of at least five thousand people, a population density of more than four hundred people per square kilometer, and over 75 percent of the male workforce engaged in nonfarm work. Between 1961 and 2001, the Indian census typically reported a few hundred CTs nationwide, but between 2001 and 2011 the number skyrocketed to 2,532. New CTs accounted for one-third of all of India’s urban population growth during this time.

In some parts of India, new census towns have emerged near large existing urban agglomerations, such as Kolkata, often associated with processes of suburbanization or peri-urbanization (Gururani Citation2020; Mondal and Samata Citation2021). But they have also increasingly emerged far from central agglomerations, in remote areas, widely scattered across the countryside (Guin and Das Citation2015; Roy and Samanta Citation2018; Van Duijne and Nijman Citation2019; Van Duijne, Choithani, and Pfeffer Citation2020). It is in these remote emergent urban formations where we focus our study.

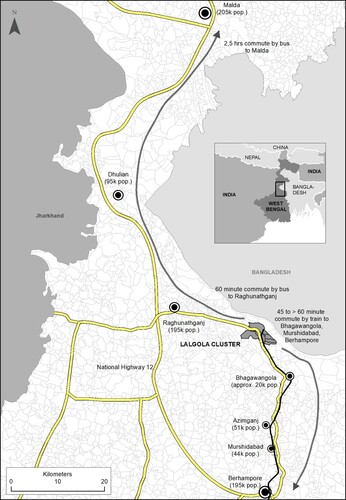

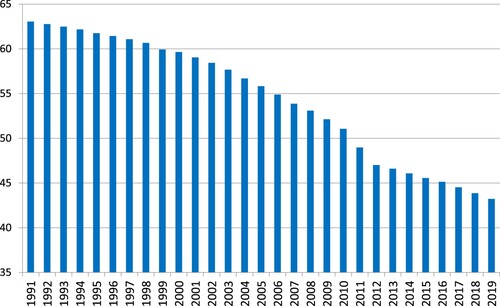

The third contextual trend, which plays out specifically in these environments, concerns substantial and ongoing declines in agrarian work. Employment studies show that over the past fifteen years, around forty million people have lost their jobs in India’s primary sector (Thomas Citation2012; Mehrotra et al. Citation2014; Abraham Citation2017). Assuming an average rural household size of five (a conservative estimate), this trend affects around two hundred million people in their livelihoods. The share of employment in agriculture in India dropped from 63 percent in 1991 to around 40 percent in 2020 (). The push out of agriculture appears to take place irrespective of alternative local employment opportunities, leaving households with major livelihood challenges. It is mainly attributed to fragmentation of agrarian lands and accompanying low yields, low wages, mechanization, and increasingly frequent poor harvests or complete crop failures (e.g., Sainath Citation2011; Government of India Citation2018; Barman and Deka Citation2019).

Figure 2. Employment in agriculture as a percentage of total employment in India.

Source: World Bank (Citation2021).

The fourth trend refers to significant increases in labor migration. Recent research shows that domestic labor migration has accelerated to unprecedented levels in the last couple of decades (Nayyar and Kim Citation2018; Tumbe Citation2018). Although existing national data in India do not fully capture the true extent of labor migration, some estimate that the stock of labor migrants in India increased nearly fourfold between 2004 and 2012, from sixteen million to sixty million; others put the number for domestic migrants to be considerably higher, ranging from eighty million to estimates of between one hundred and two hundred million people (Deshingkar and Akter Citation2009; Nayyar and Kim Citation2018). Village-level studies confirm the growing significance of circular labor migration in India (Datta Citation2016; Choithani, van Duijne, and Nijman Citation2021). At the same time, international labor migration from India, which is recorded systematically, has accelerated as well (International Labour Organization Citation2018; United Nations Citation2019). Migration from India to the Persian Gulf alone more than tripled between 2000 and 2019 to reach over nine million migrants (United Nations Citation2019). There is a substantial body of literature from rural India on labor mobility and the importance of remittances in local livelihoods (e.g., Datta Citation2016; Choithani Citation2017; Jodhka and Kumar Citation2017; Rajan and Sumeetha Citation2019; Choithani, van Duijne, and Nijman Citation2021).

These four trends, combined, provide important context for a study of the economic geographies of India’s emergent urban formations. They help set the stage for the empirical part of our study, which will offer in-depth investigations of our two case studies; they are also critically important in mobilizing relevant theoretical literatures and in the formulation of a suitable conceptual framework.

Theorizing India’s Emergent Urban Formations

Existing urban theory provides some important general directions for this study on the economic geographies of remote urbanizing regions in India. We build on and contribute to these various strands of theoretical literature, some of which have in recent years found themselves on opposing sides of intense urban theoretical debates. In the following, we touch briefly on each of these literatures, to illustrate both their relevance and limits to our inquiry. Our research for this article is conducted in the spirit of engaged pluralism (Barnes and Sheppard Citation2010), or what Van Meeteren, Bassens, and Derudder (Citation2016) call frame switching. The primary goal is not to resolve the epistemological contradictions among these different perspectives or to seek some sort of synthesis; it is to arrive at a better understanding and conceptualization of India’s remote urbanizing regions.

Urban Economic Geography and Regional Economics

The first set of literature is based in the long-standing tradition of (urban) economic geography and regional economics, with a relatively straightforward definition of what is urban, and with substantial claims of theoretical generalization. This literature is largely based in the historic experience of North America and West Europe, and it places a strong emphasis on the economic drivers of urbanization. Scott and Storper (Citation2015) argue that the universal nature of cities is found in the spatial logic of agglomeration, allowing for differentiation between urban and nonurban areas. Agglomeration refers to the dynamics of the co-location of firms and the clustering of economic activity (Fujita and Thisse Citation2013). Scott and Storper (Citation2015, 6) argue that “All cities everywhere consist of dense agglomerations of people and economic activities”; and that agglomeration is the “basic glue that holds the city together.” More recently, Scott (Citation2022) has somewhat nuanced this position, noting the importance of the city’s ambient and exogenous dimensions, and referring especially to cities in the Global South. Nonetheless, the emphasis remains on the material logic of agglomeration and the concomitant role of divisions of labor in the process of urbanization. Urban theorizing, it is suggested, ought to reach for the highest possible level of “generality and inclusiveness” (Scott Citation2022, 22).

A parallel argument in this literature holds that urban growth and economic growth generally move in tandem (e.g., Renaud Citation1979; Henderson Citation2002, Citation2010). A UN report (United Nations Citation2014, 3) states that “The process of urbanization historically has been associated with other important economic and social transformations, which have brought greater geographic mobility, lower fertility, longer life expectancy … Urban living is associated with higher levels of literacy and education, better health, greater access to social services, and enhanced opportunities for cultural and political participation.” In the words of Scott and Storper (Citation2015, 6), there is a “consistently positive empirical relationship between national rates of urbanization . . . and GDP per capita.”

A related set of writings in economic geography disputes this claim of association of urban growth with economic growth. Not coincidently, this body of work focuses mainly on cities in the Global South, where fast urban growth has not been accompanied with comparable increases in standards of living (e.g., Collier and Venables Citation2017; Henderson and Turner Citation2020). Some point to the negative effects of diseconomies of scale in megacities in the Global South (Glaeser Citation2014), but most emphasize the negative effects of economic growth lagging behind urban growth, that is urbanization without industrialization (Jedwab and Vollrath Citation2015). This seems especially salient in national economies that are highly dependent on natural resources and raw materials exports, where the economies of major cities tend to revolve around consumption, rather than production (Gollin, Jedwab, and Vollrath Citation2016). Murphy and Carmody (Citation2019) use the term generative urbanization to articulate the kind of needed urbanization in which growing cities provide a milieu for productive, resilient, and inclusive economies—the kind of urbanization that appears to be lacking in their case study of Dar es Salaam and other African cities.

However, as we pointed out in the previous section, the argument about urbanization without industrialization does not seem to apply to India. The Indian experience, in fact, suggests the opposite: in recent decades, economic growth has accelerated while urban growth rates have decelerated. India’s urban growth and the urban share of the total population are well below those of most African countries. Perhaps it is not surprising that India is conspicuously absent in most studies on urbanization without industrialization. Another important limitation of these literatures, for our purpose, is that they focus on the workings of major cities, not on processes of incipient urbanization at the base of the urban system.

Postcolonial Urbanism

Another strand of literature departs from a primary focus on the economic drivers of urbanization and views cities from a more emphatic postcolonial perspective. Postcolonial views in urban studies have come to the fore with the growing attention of researchers to developments in the Global South. Robinson (Citation2006) contends, persuasively, that postcolonial urban studies should exploit the potential for theorizing in a broad range of different geographic settings. It is argued that traditional theorizing is based in the historic experience of North America or Western Europe and, as such, is particularist. Parnell and Robinson (Citation2012, 598) posit that “the available stock of urban and planning theory is largely unsuited to help us understand and navigate the complex lived realities of citizens in the global South.” In a similar vein, Sheppard, Leitner, and Maringanti (Citation2013, 893) advocate a “provincializing global urbanism [that] creates space from which to challenge urban theories that treat Northern urbanization as the norm.”

If early postcolonial interventions served as a compelling deconstructive critique of Western-biased theory, more recent writings have gone a step further in problematizing the notion of the urban Global South itself. Simone (Citation2020, 605) makes the point that earlier notions of the Global South, serving “as a trope for a divergent urbanism, an ontologically distinct amalgam of urban zones constituted by shared subjections to colonialism and underdevelopment,” have made way for the Global South as a window into what seems an endlessly variegated urban world that elucidates “the need to consider a broader multiplicity of places, histories, and processes.”

Postcolonial perspectives underscore the significance of historic and geographic context, and they highlight the ways in which economic dimensions of urbanization (long the preserve of urban economic geography) are enmeshed with political institutions and cultural fabric. This is expressed in alternative urban theorizing such as Roy’s (Citation2005, Citation2009) perspective on institutionalized informality in the production of urban space (also see Banks, Lombard, and Mitlin Citation2020), and Simone’s (Citation2004, Citation2021) conceptualization of people as infrastructure. Each argues a different logic of how cities work, at least for poor and marginalized urban populations; a logic that is far removed from most of the economic geography literature discussed above.

The postcolonial urban literature is hardly different, however, in terms of its predominant focus on major cities (a legacy, perhaps, of its early critiques of allegedly false binaries of successful Western global cities versus problematic southern megacities). Much postcolonial writing is biased toward cities such as Mumbai, Johannesburg, São Paulo, or Lagos. Few writings pertain to urbanization processes in formerly rural environments. In an exceptional set of studies that concentrates on smaller settlements outside the metropolitan shadow in India, Denis, Mukhopadhyay, and Zérah (Citation2012), Denis and Zérah (Citation2017), and Mukhopadhyay, Zérah, and Denis (Citation2020) advance the notion of subaltern urbanization. Inspired by the well-known literary tradition of subaltern theory (e.g., Spivak Citation1988), the authors use the term to connote a sort of hitherto unseen, vibrant, dispersed, urbanization that is argued to be sustainably generated and propelled through local agency. This small-town urbanism is viewed as “independent of the metropolis and autonomous in their interactions with other settlements” (Denis, Mukhopadhyay, and Zérah Citation2012, 52).

This notion of subaltern urbanism, especially when defined as vibrant, autonomous, or sustainable, is questioned by other researchers. In a case study of a small town in Karnataka, Iyer (Citation2017, 115) notes that “Subaltern urbanization is defined as being autonomous, economically vital and independent of the metropolis” but that the experience of the town of study “does not neatly fit into this description” (see Shaw Citation2019 for a similar assertion based on her work in the Indian state of Bihar). Specifically, Iyer points to anecdotal reports of the importance of circular labor migration to large cities and remittances sent back home, driving construction and urban growth. This is corroborated by Choithani, van Duijne, and Nijman (Citation2021), who provide strong evidence of the reliance of households at India’s rural–urban transition on circular labor migration and remittances. Their findings point to critical connections between India’s emergent urban formations and central agglomerations elsewhere.Footnote1

Planetary Urbanization

The third strand of theoretical writings of relevance to this study concerns the planetary urbanization literature. This literature generally aligns with postcolonial critiques on the alleged singular definition of the city in conventional urban theory. On the other hand, it stands in contrast to postcolonial views of provincialization as it sets forth an alternative theoretical framework with claims of wide-ranging (planetary) applicability. The latter contrast in perspectives was documented, in all its intensity, in a special issue of Environment and Planning D in 2018 (Peake et al. Citation2018).

In two well-known earlier articles, Brenner and Schmid (Citation2014, Citation2015) call for a “new urban epistemology,” arguing that conventional definitions of urban are “theoretically incoherent” and “empirically untenable” (Brenner and Schmid Citation2014, 734). In their view, processes of urbanization have emerged across the world that are intrinsically incompatible with established conceptualizations in which the urban is spatially “fixed” and “bounded” (Brenner and Schmid Citation2015, 151). Borrowing from Lefebvre (Citation1970), they emphasize the concept of extended urbanization: spaces potentially far and wide from large urban agglomerations that are nonetheless strongly influenced by urban processes. The urban fabric is argued to extend across the planet.

The planetary urbanization perspective is of interest to our study because, first, it shifts the analytical focus from the city to the urban. Clearly, sites of remote, incipient, urbanization are not full-fledged cities—our inquiry is, rather, into the nature of their urbanizing experience. Second, the notion of extended urbanization specifically applies to urbanization processes in settings away from major agglomerations, with attention to interrelationships between concentrated and extended urbanization.

However, the planetary urbanization framework is conceptualized at such a level of abstraction that it is difficult to mobilize for our purpose without considerable further specification and/or alteration. It also explains why the notion of extended urbanization means different things to, and is used differently by, different scholars (e.g., compare Monte-Mór Citation2014; Keil Citation2018; Ghosh and Meer Citation2021). The alleged lack of contextual specificity (or, some would argue, of acknowledged positionality) that accompanies claims of planetary theoretical validity has been an important source of criticism from the postcolonial literature.

In addition, the strong emphasis, in the planetary framework, on theorizing urban processes, rather than spatial form (in view of the conceived relentless and ceaseless reorganization of global urban space), appears at odds with our own approach. Brenner and Schmid (Citation2015, 176) contend that the “search for . . . ‘new’ urban forms is an intellectual trap” and that a focus on urban patterns or morphology “yields only relatively superficial insights.” Our own approach, in this research, prioritizes an analysis of shifting spatial arrangements to elucidate ongoing processes, and vice versa.

Conceptual Framework

Each of these literatures offer important insights, but each has limitations when applied to a research focus on India’s urbanizing periphery. As noted earlier, and with an eye on the exploratory nature of this research, our overall approach is built on the notions of engaged pluralism, transduction, and frame switching. Our conceptual framework revolves around three broad arguments that emanate from these theoretical literatures above and from our own previous work at these sites. We will substantiate these arguments in the rest of the article.

The first argument, conforming to established urban economic geography, is that shifting divisions of labor are a major driving force in incipient urbanization in India’s periphery. Given that this shift is taking place across extensive heretofore agricultural regions, the formations are dispersed and are relatively small. The employment shift is accompanied with local economic restructuring in terms of production and exchange. However, local agglomeration processes and employment opportunities are quite limited. Thus, while the agricultural base of the local economy largely disappears, it is not necessarily replaced by a local urban economy.

Second, the role of migration in these emergent urban formations is expected to be entirely different from prevailing Western models: in the absence of significant local agglomeration processes, in-migration is limited due to a lack of local employment opportunities, and so is local population growth on account of migration. At the same time, out-migration is predictably modest, given India’s slow aggregate urban growth and the exclusionary nature of many of its big cities (Kundu Citation2014). Thus, these are neither fast-growing urbanizing areas, nor shrinking rural towns, and demographically they are relatively stable. Significantly, the lack of local economic opportunities gives way to circular male labor migration (while the rest of the household stays put). This is not the kind of seasonal circular labor migration that has historically characterized rural India, at a time that migrants and their families still relied mainly on agricultural work, and when seasonal work elsewhere was based on the local agricultural seasonal cycle. We argue that, today, male circular labor migration is permanent in the sense that this is the worker’s only or primary employment, and the worker is gone from home most of the year. Nonagricultural incomes are now the norm for most households (Choithani, van Duijne, and Nijman Citation2021).

Third, the disproportionate role of remittances from labor migrants in the local economy and in local processes of urbanization is thought to result in a form of injected urbanismFootnote2: urban growth that relies largely on the infusion of capital generated elsewhere. Remittances are a major source of income for many households and often far exceed locally earned incomes. They can fuel a consumer-oriented local economy, provide funding for start-up companies (often retail), and finance construction and urban expansion. Clearly, these emergent urban formations are not autonomous, and their sustainability and resilience are not self-evident. We argue that injected urbanism is inherently a geographically relational, interdependent, and scalar phenomenon. As we will elaborate below, these emergent urban formations are simultaneously shaped at local, regional, and (inter)national scales.

Study Design and Selection of Case Studies

The empirical study was conducted in three stages: (1) the creation of a geographic information system (GIS) using relevant existing data (mainly from the Indian census), (2) on-the-ground reconnaissance visits to a range of potential case-study sites, and (3) in-depth data collection at the two selected study sites.

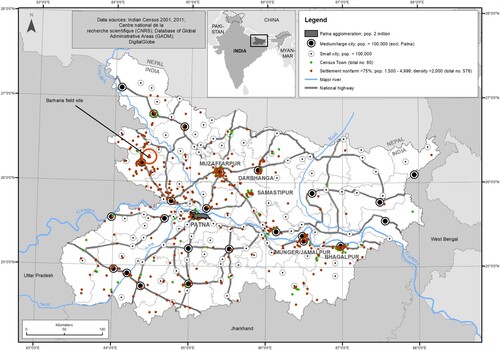

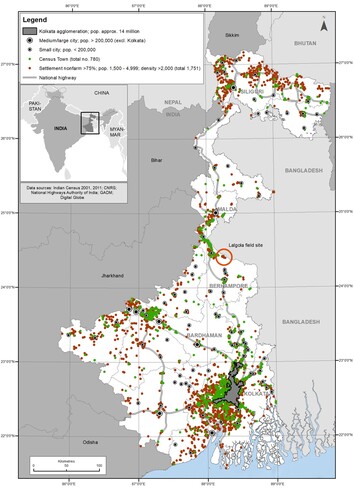

Our GIS covered the states of Bihar and West Bengal, with current overall populations of about one hundred million and ninety million, respectively, selected because of their contrasting urban profiles (as outlined below). We gathered data on population size, density, and workforce for all 86,000 census units of these states for 2001 and 2011, and we connected this database to spatial boundary files. and highlight all urban-classified census towns and settlements that have exceeded 75 percent of the workforce in nonfarm employment but that have not (yet) reached a size of five thousand people to be categorized as CTs. The latter are the red dots on the maps, places we call high nonfarm settlements. All these settlements show a substantial decline in agrarian employment between 2001 and 2011.

Figure 3. Bihar’s evolving urban system, including census towns and high nonfarm settlements.

Source: Authors’ adaptation of census data.

Figure 4. West Bengal’s evolving urban system, including census towns and high nonfarm settlements.

Source: Authors’ adaptation of census data.

According to the 2011 census, the share of India’s total population living in urban areas was 32 percent. For West Bengal, with a population of about ninety million, it was 31.9 percent; for Bihar, with a population of about one hundred million, it was reported at only 11.3 percent. In 2011, Bihar had 52 new census towns and 576 villages with more than 75 percent in nonfarm employment; West Bengal had 537 new census towns and 1,751 villages with over 75 percent in nonfarm employment. Our GIS analysis indicated that the built environments of many of the nonfarm settlements are amalgamating, forming substantial and relatively populous clusters that together (far) exceed the five thousand–population level for census towns. Since the census does not consider spatial contiguity of administrative units, it does not detect or report such urban growth.

The second stage of the research design involved ten reconnaissance field visits (five in Bihar and five in West Bengal). These served to ground truth the urban growth (clustering and amalgamation) detected in our GIS and to select case study sites for primary data collection. Most sites showed infrastructural improvements that have been implemented across India in recent years. In both states, road density roughly doubled between 2003 and 2017 (Government of India Citation2019), creating a potential for increased regional economic integration.

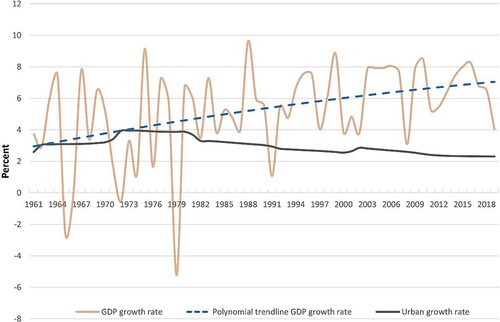

We selected two sites: one in western Bihar around the settlement of Barharia and another in central West Bengal around the settlement of Lalgola ( and ). Both clusters consisted entirely of nonurban settlements; that is, they were made up exclusively of high nonfarm settlements and did not contain any CTs (yet). Little is known about these settlements, yet they provide the décor to what is arguably the earliest (and most invisible) stage of the rural–urban transition. At the same time, the two clusters are quite different from each other in terms of population size and density; they also appeared different in terms of the stage of the rural–urban transition, with the larger Lalgola cluster apparently further along and more established than the Barharia cluster ( and ).

Figure 5. The Lalgola cluster and constituent census units.

Source: Authors, based on census data and remote sensing imagery (basemap layer: ESRI ArcGIS/DigitalGlobe, World Imagery, n.d.).

Figure 6. The Barharia cluster.

Source: Authors, based on census data and remote sensing imagery (basemap layer: ESRI ArcGIS/DigitalGlobe, World Imagery, n.d.).

The Barharia cluster consists of six settlements with a combined population of almost twenty thousand people. The overall share of male nonfarm workers is 82 percent, up from 42 percent in 2001. The Lalgola cluster consists of seven contiguous settlements with a combined population of ninety thousand. Its share of male nonagricultural workers is 79 percent, up from 70 percent in 2001. Barharia’s population increased by 29 percent between 2001 and 2011, somewhat above Bihar’s state average of 25 percent (the all-India average is 18 percent). Lalgola’s population increased by 19 percent, on a par with the all-India average, and slightly higher than the 14 percent growth figure for the state of West Bengal. Most of the population growth of the two clusters resulted from natural growth, and both sites experienced little in-migration.

Both sites have relatively high population densities and experienced densification between 2001 and 2011. Barharia’s density exceeded 2,000 people per square kilometer in 2011 (the Bihar average was 1,100), and it increased by 34 percent since 2001 (Bihar’s average was 26 percent). The Lalgola cluster is very dense indeed, with 5,750 people per square kilometer in 2011, 14 times higher than the 400-density threshold for urban status. Lalgola’s densities increased by 21 percent (West Bengal’s average was 14 percent). and give an impression of urban growth in the two clusters.

Figure 7. The western edge of the Barharia cluster, showing recent new construction along the urban development boundary in 2019.

Source: Photo by authors.

Figure 8. New high-rise construction in central Lalgola in 2019. Densification and areal expansion of the built-up environment was observed in both Lalgola and Barharia.

Source: Photo by authors.

The third stage of the study entailed primary data collection through 645 household surveys, 331 firm surveys, and 46 in-depth semistructured interviews with households and key informants. This article concentrates on findings from the household survey relating to livelihoods, occupations, commuting, and migration, and on findings from the firm surveys about the type of business, age of the firm, location, size, workers, customers, subcontracting, and supply chains. The interviews served to confirm or clarify survey data interpretations and delve deeper into motivations behind household and firm behaviors. In all, the analysis seeks to shed light on the evolving economic geographies at the two sites and on the accompanying nature of urbanization.

The Economic Geographies of India’s Urbanizing Periphery

Following the multiscalar conceptualization of urbanization in the theoretical framework, the analysis is organized at three scales. The local pertains to the cluster itself; the regional refers to linkages between the cluster and surrounding area, including larger towns; and the (inter)national pertains to networks of labor migration (and supply chains) from the clusters to major urban centers in India or abroad.

The Local Scale: Employment Shifts and Economic Restructuring

The shift of employment out of agriculture is arguably the most fundamental force behind India’s rural–urban transition. shows the share of main breadwinners currently (2019) and previously engaged in farming. Currently, at both sites, less than 9 percent of main breadwinners are employed in the agrarian sector. Further, 22 percent of main breadwinners in Barharia and 10 percent in Lalgola indicated that they previously worked in agriculture. The employment shift can also be observed across generations, with agricultural jobs more common among the fathers of current breadwinners. These numbers indicate that Barharia’s transition is more recent than Lalgola’s.

Table 1 Occupational Shifts out of Agriculture, for Households Living in the Barharia and Lalgola Clusters

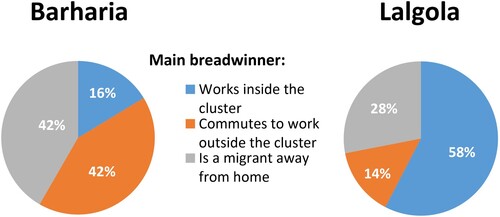

shows that a considerable number of these breadwinners (of households living inside the cluster) work outside the cluster, especially so in Barharia. Many rely on employment at commuting distance in the region or on labor migration away from home. The Lalgola cluster offers more employment opportunities than Barharia, in part a function of its larger size. For now, let us continue to focus on the local level.

Figure 9. Geographies of employment in Barharia (N = 308) and Lalgola (N = 337).

Source: Authors’ household surveys, 2019.

shows that of all breadwinners living and working inside the cluster, many have turned to entrepreneurship (61 percent in Barharia, 42 percent in Lalgola). This mainly concerns retail shops, plus some other forms of self-employment. Interview data confirmed that the salience of entrepreneurship is in part due to a lack of other local employment opportunities and, in some cases, is made possible by remittances. The second largest occupational category are nonfarm manual workers (22 percent in Barharia, 24 percent in Lalgola): drivers, bidi makers, brick kiln workers, barbers, tailors, retail workers, repair workers, etc. The share of educated professionals living and working in the clusters is negligible (0 percent in Barharia, 2 percent in Lalgola).

Table 2 Current Occupations of Main Breadwinners Living in the Barharia and Lalgola Clusters, Who Work inside the Clusters (as a Percentage of All Workers inside the Cluster)

Firms are generally very small. In Barharia, over 60 percent of firms operate from premises smaller than two hundred square feet (<18.5 m2), compared to almost 40 percent in Lalgola. Nearly a third of all firms do not have any employees besides the owner, and nearly 70 percent have less than two employees (often family members), suggesting that local companies do not provide ample employment opportunities to local populations. The firms in Lalgola are substantially older than those in Barharia, another signal that Barharia’s rural–urban transition is more recent than that of Lalgola. As shows, at both sites, firms are overwhelmingly in retail, selling garments, jewelry, shoes, school materials, or electronics, and are part of a small-scale, retail-oriented economy. Consumer services cover a variety of other small companies, for example, printing and copying firms, travel agents, and small financial firms offering money transfer and money exchange services.Footnote3

Table 3 Sectoral Composition of the Barharia and Lalgola Firms

Manufacturing has only a minor presence. These firms include furniture makers, tailors, potters, manufacturers of gates, etc. Many produce on demand for local customers, thus combining manufacturing and retail. Unlike Barharia, Lalgola has a few small food processing manufacturers, one chemical manufacturer, and a raw jute handling firm. The latter is a remnant of the area’s past as an important jute-growing region that has been in decline for several decades now (almost all value-added processing of jute is done in Kolkata).

Due to the size difference between the two clusters, Lalgola benefits more from economies of scale, though the effects seem quite modest. It is expressed, for example, in Lalgola’s larger shares of workers in the public sector and in hawking, each of which clearly require threshold populations (). In Barharia, such activity is virtually nonexistent. Still, even in Lalgola, many of these workers need to commute outside the cluster, to larger towns, for work.

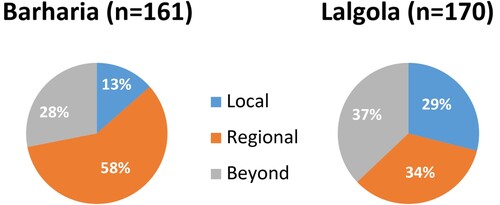

At the local level, there is no clear evidence of agglomeration processes in the sense of horizontal or vertical linkages. Knowledge spillovers are likely to be of some importance in the (growing) retail business, but there is only so much knowledge to be shared in this sector. In addition, labor pooling appears insignificant in Barharia, and it probably plays only a modest part in Lalgola’s public sector and in its small manufacturing sector. Only very few firms (5 percent) across both clusters reported to be involved in subcontracting at the sending or receiving end. Finally, firm inputs originating from within the cluster are very modest. In Lalgola, only 29 percent of firms report that most of their supplies come from inside the cluster; in Barharia it is a mere 13 percent. A considerable share of business supplies in the clusters comes from the surrounding region, especially so in Barharia (58 percent); and, for both sites, roughly a third comes from beyond the region.

Before we turn to the regional scale of analysis, it is important to make a comparative observation of the rural–urban transition at the sites. Lalgola’s transition has been under way longer, and the cluster contains a larger and more densely packed population; it has a small public sector and some manufacturing activity that would be hard to sustain with a population the size of Barharia; and considerably more people work inside the Lalgola cluster than in the Barharia cluster. But the overall structure of the local economy in both places is quite similar: at both sites, the retail sector is very dominant, firms are small, and agglomeration effects are hard to detect. In other words, the economy of the Lalgola cluster, while bigger and older, does not seem to have evolved much in comparison with Barharia.

Regional Linkages

We define the region as the area within commuting distance of the respective clusters. For Barharia (), the region stretches about ten to twenty miles in different directions. It includes five surrounding towns. The two largest and most important are Siwan, to the west, and Gopalganj, to the north, with populations of 135,000 and 67,000, respectively. The three smaller towns are Barauli, Mirganj, and Tarwara. Their populations range between ten thousand and forty thousand. The most common means of transport for commuters is by motorcycle.

The Lalgola region () is larger and extends about twenty-five to sixty miles in different directions. It is surrounded by six towns: Bhagwangola, Murshidabad, and Berhampore, all to the south; Raghunathganj, to the west; and Dhulian and Malda, to the north. The region in some ways reflects West Bengal’s higher level of urbanization, compared to Bihar: as noted before, the Lalgola cluster is much larger than the Barharia cluster, and Lalgola’s surrounding towns, too, are generally larger (three of them around two hundred thousand people). Distances are larger, too, and the means of transportation include buses and trains.

Figure 12. Geographic origins of the majority of supplies to firms in Barharia and Lalgola.

Source: Authors' firm surveys, 2019.

As indicated, of all main breadwinners in Barharia, 42 percent commute to work outside the cluster; for Lalgola, the number is 15 percent. This difference is mainly due to the variation in size: since Lalgola is larger, it is more likely to provide employment inside the cluster. At any rate, for both clusters, the share of commuters is considerably higher than general estimates of rural-to-urban commuters in India of around 9 percent (Chandrasekhar Citation2011).

In terms of the occupational status of commuters, the largest share is comprised of nonfarm manual workers and construction workers: 51 percent in Barharia and 38 percent in Lalgola. This group includes daily wage workers, either skilled (masons, plumbers, welders, carpenters, etc.) or unskilled. In the Lalgola case, daily wage workers commute to any of the three larger regional towns where they gather at designated labor chowks. In the Barharia case, most go to Siwan. The operations of daily wage work depend on economies of scale, and they are an example of labor market pooling, a key mechanism in agglomeration processes as conventionally understood. Apparently, some of such agglomeration processes are at work in the larger surrounding towns but not in the clusters themselves. Among Barharia commuters, there are also many business (shop) owners who require a larger market than what is available in the cluster itself (29 percent of all commuters, compared to 8 percent in Lalgola). All of the (few) educated professionals living in Barharia also commute to the larger surrounding towns. Finally, a substantial share of Lalgola’s commuters hold government jobs in the larger regional towns (27 percent, compared to 6 percent in Barharia).

Another measure of regional economic linkages pertains to supply chains. shows the geographic origins of supplies to firms in the two clusters. A relatively small share of inputs comes from within the clusters, suggesting limited vertical linkages at the local level. For Barharia, the regional scale is far more important (58 percent). In Lalgola, the origin of supplies is split evenly in thirds between the local, regional, and national scales. Regional supplies for Lalgola mostly come from the larger town of Berhampore, and inputs from beyond the region mostly hail from Kolkata. The supply network is more developed in Lalgola than in Barharia, with an important role for a few transport companies that are actually based in the Lalgola cluster. Interview data indicated that these transport companies make daily runs to Kolkata. They carry jute to Kolkata and bring retail products back to Lalgola: food, tea and coffee, cosmetics, clothes, towels, computer and mobile phone parts, etc. Many Lalgola firms have arrangements with these transportation companies. It is another sign of the (modest) economies of scale that can be found in Lalgola and less so in the smaller Barharia cluster.

Thus, it is clear that the changing economic geographies of these emergent urban formations are not isolated at the local scale and that regional linkages play an important role. Barharia and Lalgola are quite distinct from India’s archetypal rural villages that have a dominant primary sector and low levels of commuting (Chandrasekhar Citation2011). At our two sites, economic restructuring is in some very concrete ways dependent on, and embedded in, the surrounding region.

The (Inter)national Scale: Labor Migration and Injection of Remittances

In addition to the local and regional scales, the rural–urban transition plays out at the national and international scales, in the form of circular labor migration and remittance flows. indicated that 42 percent of main breadwinners in Barharia and 28 percent of main breadwinners in Lalgola are labor migrants. If we consider other household members who are migrants besides the main breadwinner, the numbers go up further: in Barharia, 52 percent of households have one or more labor migrants; in Lalgola, it is 38 percent. This salience of labor migration underscores the limited livelihood opportunities in the two clusters, locally and within the region.

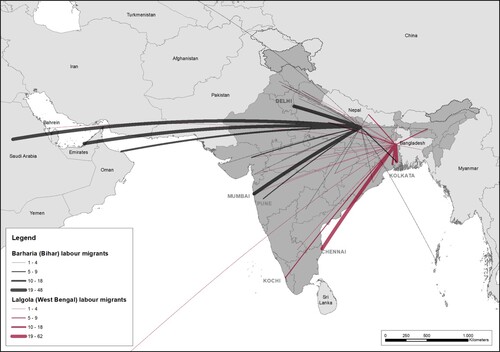

Labor migration is especially prominent in Barharia and it is starkly different from Lalgola in that half of the migrants work abroad, while in Lalgola virtually all labor migration is domestic (we found only seven households with international migrants, most working in Nepal). Barharia is connected to India’s large western cities (Mumbai, Delhi, Pune) and to destinations in the Persian Gulf: Saudi Arabia, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar. Labor migration from Lalgola is mostly southward, to Kolkata and farther-away to Chennai and Kochi ().

Figure 13. Labor migration flows from Barharia and Lalgola.

Source: Authors' household surveys, 2019.

These outward flows of labor migration reflect the nonconventional nature of incipient urbanization at the two sites. In established (Western) theory, urbanization is associated with permanent in-migration and this, in turn, is driven by urban employment opportunities. But in-migration into the two clusters is quite minimal, and most population growth is due to natural increase. Nor do the clusters witness one-way out-migration of households from the clusters to larger urban centers as is considered typical in conventional theory for rural areas.

The influx of remittances from labor migration, in turn, is found to play a critical role in the local economy and in local processes of urbanization (also see Taylor Citation1999; Jodhka and Kumar Citation2017). This applies to both clusters, but it is especially true for Barharia, which has more households with labor migrants and a large number of international migrants (which are virtually absent in Lalgola). The earnings of international migrants are much higher than those of domestic migrants: the average annual income of a household with labor migrants in Barharia is Rs. 374,197 (about $5,000), compared to Rs. 205,862 in Lalgola (about $2,800).

First, remittances drive consumption, thereby supporting the retail sector. In the case of Barharia, they also explain the presence of a small tertiary sector comprised of expensive private schools and private health care clinics. Second, remittance capital is instrumental in the start-up of new companies. Across the two sites, 36 percent of entrepreneurs reported to have relied on their own or relatives’ remittances in the start-up of their firm. Third, remittances are used to construct new, larger, homes or to fund home expansions (more than half of all surveyed households reported that they constructed their current home in the past ten years), driving densification and areal expansion of the clusters and amalgamation of settlements.

Thus, in addition to the regional scale, the (inter)national scale is of key importance to the economic geographies of emergent urban formations. Remittances can be viewed as exogenous drivers of urbanization in these localities, resulting in a kind of injected urbanism. Remittances help facilitate the shift of employment out of agriculture, fuel entrepreneurship and a consumption- and service-oriented economy, and finance construction and expansion of the built-up environment. This injected urbanism is propelled and maintained not through local processes of agglomeration but via the infusion of capital from activities elsewhere.

Conclusions

Our research seeks to elucidate processes of urbanization in India’s remote rural regions and to build on current strands of urban theory. As noted earlier, the postcolonial literature provides important openings for such endeavors with its intent to bring into view urban processes in heretofore underexplored environments (Robinson Citation2006). Theoretically reflexive empirical research is essential to that purpose (Nijman Citation2015a). We employ a strategy of transduction and frame switching, allowing us to consider various theoretical perspectives in a constant interplay with empirical observation (Van Meeteren, Bassens, and Derudder Citation2016; Schmid et al. Citation2018).

We find that urbanization processes in Barharia and Lalgola are fundamentally driven by changing divisions of labor, conforming to established economic urban geography (e.g., Scott and Storper Citation2015). The momentous shift of employment out of agriculture and into the secondary and tertiary sectors is the primary driver of the restructuring of local economies. Since this employment shift takes place across large swaths of India’s erstwhile agricultural regions, the resulting emergent urban formations are highly dispersed and relatively small. At the same time, local agglomeration processes are not very significant or, in the case of Barharia, virtually absent. Local economies are increasingly oriented toward consumption with considerable activity in retail (the goods are typically produced elsewhere) and consumer services such as education and health care. There is little to be observed in terms of sharing, matching, or knowledge spillovers, and vertical or horizontal linkages within these local economies are negligible.

The processes of urbanization at our study sites also deviate, fundamentally, from conventional Western urbanization models in respect to the role of migration. In-migration is modest and permanent out-migration is virtually absent, resulting in only modest growth and relatively stable local demographics. What is critically important, however, is the salience of permanent circular (male) labor migration. It is permanent circular because it no longer relates to the seasonal agricultural cycle, from which livelihoods have become almost entirely divorced. Male labor migration is a consequence of the dearth of alternative local livelihood opportunities, combined with the risks and high costs (economically and socially) associated with one-way rural–urban migration of the entire household (Choithani, van Duijne, and Nijman Citation2021).

In turn, it is the infusion of the very considerable remittances, relative to other income sources, that steers the restructuring of the local economy and that shapes a process of urbanization and resulting urban form we refer to as injected urbanism: an urbanization process that is primarily driven exogenously. As such, it is linked to, and dependent on, economic activity in other places.

This observation runs counter to suggestions of the relative autonomy or self-reliance of small and emergent Indian towns inherent in the subaltern urbanism argument (Mukhopadhyay, Zérah, and Denis Citation2020). We find compelling evidence of the multiscalar nature and critical connections of these emergent urban formations to the surrounding region and to faraway cities.Footnote4 If India’s urbanizing periphery can be viewed in terms of extended urbanization, it is one characterized by mutual dependencies between these emergent urban formations, the surrounding regional economies, and distant central agglomerations.

Our findings also underscore the usefulness of a simultaneous research focus on process and place, contrary to what has been suggested in the planetary urbanization literature. Brenner and Schmid (Citation2015) contend that, in the development of a new epistemology of the urban, the emphasis should be on process rather than place. That view, which seems innately difficult to digest by geographers, is based in the assumption that present-day urban processes no longer produce identifiable spatial arrangements. Our research suggests otherwise. India’s emergent urban formations are dynamic places, but they are identifiable. Our two study areas, at least, have a clear spatial signature, and they are relatively stable formations. They are dispersed, relatively small, amalgamating, urbanizing areas with a particular economic profile and with vital external connections. The built-up environments of Barharia and Lalgola reflect injected urbanism in terms of expanding and densifying residential areas and much less so expanding economic activity other than retail and consumer services. We would argue that the search for new urban forms is an intellectual trap only when they are presented as universal, immutable, models.

What is the prospect of these emergent urban formations? How stable are they? Some clues can be found in the different histories of Lalgola and Barharia. It is important to reiterate that while the Lalgola cluster is older and has been in transition longer, this has not translated into a differently structured local economy, in comparison with Barharia. Both are dominated by retail and consumer services, both have small firm sizes, and both rely very substantially on employment elsewhere. Lalgola’s longer history of urbanization, or time spent in transition, has not translated into higher levels of well-being than in Barharia, or a substantially different occupational structure. From a conventional theoretical point of view, one could argue that the absence of agglomeration processes will preclude a maturing of urban growth and that these places will remain sites of stagnant incipient urbanization. Maybe this has already been the case for Lalgola. That particular framing, however, carries the risk of once again forcing the experiences of India’s emergent urban formations into existing (northern) urban models. A more useful reading, we think, is that Barharia’s and (especially) Lalgola’s urban formations are, in fact, more or less stable and should be understood as they are: dispersed sites of injected urbanism within predominantly rural environments, highly dependent on economic activity elsewhere.Footnote5

At the same time, the long-term sustainability of this kind of injected urbanism may be precarious. If these urbanizing formations are exogenously generated, their resilience can be put to the test by circumstances well beyond local control. Our data collection for this article was completed in late 2019, on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is thought to have disturbed the livelihoods of many labor migrants and their families (Inani Citation2021), with possible reverberations across these local economies. Changing employment opportunities or changing immigration or labor laws in receiving countries can also drastically impact labor migration and, indirectly, the prospects of these emergent urban formations.

We think our case studies are representative of many localities in India’s urbanizing periphery in the Gangetic Plain (along with expected idiosyncratic variations, as between the two cases), particularly settlements that have not yet become census towns but that are witnessing rapidly decreasing agrarian employment and increased labor migration. The notion of injected urbanism may well be relevant to other parts of Asia, where employment shifts out of agriculture are accompanied with a rise in permanent circular labor migration and significant remittances (e.g., Keyes Citation2012; Rigg, Salamanca, and Parnwell Citation2012). In India, at least, this social transformation is challenging the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people, and it is closely related to a process of urbanization that we are only just beginning to understand.

Acknowledgments

We thank all respondents for participating in this study and our local field research assistants Anamika, Asim, Jitendra, Malati, Shree Bhagwan, and Subir for their help with fieldwork. Arindam Das of the Institute of Health Management Research provided useful guidance on survey sampling and fieldwork logistics. Eric Denis and his team at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) provided micro-census boundary files of Bihar and West Bengal’s administrative units and we are thankful to them. Early findings of our research were presented at the Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta (IIM-C), the Indian Institute of Technology, Patna (IIT-P), and the International Sociological Association’s RC21 conference in Delhi in September 2019. We thank all participants for their comments, which helped strengthen this article. We are particularly grateful to Rajesh Bhattacharya and Annapurna Shaw of IIM-C, and Nalin Bharti, Aditya Raj, and Papiya Raj of IIT-P for valuable discussions and feedback.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 There is a considerable literature on the economic significance of remittances in developing economies, but it focuses overwhelmingly on the national scale or on the general impact on agricultural productivity (e.g., Stark Citation1991; Taylor Citation1999); it typically does not pay attention to localized processes of urbanization.

2 We are grateful to Dr. Papiya Raj, who suggested the term injected urbanism during a discussion of our research at IIT-Patna in September of 2019.

3 also shows that Barharia has more private education and health care providers, even if it is smaller than Lalgola. One explanation is that Barharia’s population can afford more expensive private health and educational services due to the higher remittances it is receiving from labor migrants, compared to Lalgola. We will return to this matter shortly.

4 This is not to deny the importance of local agency: here and elsewhere we have emphasized the importance of decision-making by firms and households, especially in regard to labor migrants (Choithani, van Duijne, and Nijman Citation2021).

5 This apparent stability, from a social rather than an economic perspective, may also rest in part in the long history of male seasonal labor migration in many rural parts of India, one that predates the more recent structural loss of jobs in agriculture (De Haan Citation2002).

References

- Abraham, V. 2017. Stagnant employment growth: Last three years may have been the worst. Economic and Political Weekly 52 (38): 13–17.

- Banks, N., Lombard, M., and Mitlin, D. 2020. Urban informality as a site of critical analysis. Journal of Development Studies 56 (2): 223–38. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2019.1577384.

- Barman, S., and Deka, N. 2019. Effect of farm mechanization in human labour employment. International Journal of Agricultural Science 4:16–22.

- Barnes, T. J., and Sheppard, E. 2010. ‘Nothing includes everything’: Towards engaged pluralism in Anglophone economic geography. Progress in Human Geography 34 (2): 193–214. doi: 10.1177/0309132509343728.

- Bhagat, R. B. 2012. A turnaround in India’s urbanization. Asia-Pacific Population Journal 27 (2): 23–39. doi: 10.18356/43dd15e8-en.

- Brenner, N., and Schmid, C. 2014. The ‘urban age’ in question. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (3): 731–55. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12115.

- Brenner, N., and Schmid, C. 2015. Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City 19 (2–3): 151–82. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2015.1014712.

- Chandrasekhar, S. 2011. Workers commuting between the rural and urban: Estimates from NSSO Data. Economic and Political Weekly 46 (46): 22–25.

- Chatterjee, U., Murgai, R., and Rama, M. 2015. Employment outcomes along the rural–urban gradation. Economic and Political Weekly 50 (26–27): 5–10.

- Choithani, C. 2017. Understanding the linkages between migration and household food security in India. Geographical Research 55 (2): 192–205. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12223.

- Choithani, C., van Duijne, R. J., and Nijman, J. 2021. Changing livelihoods at India’s rural–urban transition. World Development 146 (October): 105617. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105617.

- Collier, P., and Venables, A. J. 2017. Urbanization in developing economies: The assessment. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (3): 355–72. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grx035.

- Datta, A. 2016. Migration, remittances and changing sources of income in rural Bihar (1999–2011): Some findings from a longitudinal study. Economic and Political Weekly 51 (31): 85–93.

- De Haan, A. 2002. Migration and livelihoods in historical perspective: A case study of Bihar, India. Journal of Development Studies 38 (5): 115–42. doi: 10.1080/00220380412331322531.

- Denis, E., and Zérah, M. H., eds. 2017. Subaltern urbanisation in India: An introduction to the dynamics of ordinary towns. New Delhi: Springer India.

- Denis, E., Mukhopadhyay, P., and Zérah, M. H. 2012. Subaltern urbanisation in India. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (30): 52–62.

- Deshingkar, P., and Akter, S. 2009. Migration and human development in India. Human Development Research Paper 2009/13. New York: United Nations Development Programme. https://hdr.undp.org/content/migration-and-human-development-india.

- Fujita, M., and Thisse, J. F. 2013. Economics of agglomeration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ghosh, S., and Meer, A. 2021. Extended urbanisation and the agrarian question: Convergences, divergences and openings. Urban Studies 58 (6): 1097–119. doi: 10.1177/0042098020943758.

- Glaeser, E. L. 2014. A world of cities: The causes and consequences of urbanization in poorer countries. Journal of the European Economic Association 12 (5): 1154–99. doi: 10.1111/jeea.12100.

- Gollin, D., Jedwab, R., and Vollrath, D. 2016. Urbanization with and without industrialization. Journal of Economic Growth 21 (1): 35–70. doi: 10.1007/s10887-015-9121-4.

- Government of India. 2011. Primary census abstract data: Census of India 2011. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. https://censusindia.gov.in/census.website/

- Government of India 2016. State of Indian agriculture 2015–16. New Delhi: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. https://agcensus.nic.in/document/agcen1516/ac_1516_report_final-220221.pdf.

- Government of India 2018. Agriculture census 2015–2016. New Delhi: Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. https://agcensus.nic.in.

- Government of India 2019. Basic Road Statistics of India 2016–17. New Delhi: Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. https://morth.nic.in/sites/default/files/Basic%20Road%20Statics%20of%20India%20CTCcompressed1.pdf.

- Guin, D., and Das, D. N. 2015. Spatial perspectives of the new census towns, 2011: A case study of West Bengal. Environment and Urbanization ASIA 6 (2): 109–24. doi: 10.1177/0975425315589155.

- Gururani, S. 2020. Cities in a world of villages: Agrarian urbanism and the making of India’s urbanizing frontiers. Urban Geography 41 (7): 971–89. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1670569.

- Henderson, V. 2002. Urbanization in developing countries. World Bank Research Observer 17 (1): 89–112. doi: 10.1093/wbro/17.1.89.

- Henderson, V. 2010. Cities and development. Journal of Regional Science 50 (1): 515–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9787.2009.00636.x.

- Henderson, J. V., and Turner, M. A. 2020. Urbanization in the developing world: Too early or too slow? Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (3): 150–73. doi: 10.1257/jep.34.3.150.

- Inani, R. 2021. How second wave of COVID-19 has decimated India’s rural economy-India News. Firstpost, June 6, 2021. https://www.firstpost.com/india/how-second-wave-of-covid-19-has-decimated-indias-rural-economy-9689231.html.

- International Labour Organization. 2018. India labour migration update 2018. New Delhi: United Nations. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_631532.pdf.

- Iyer, S. 2017. Circular migration and localized urbanization in rural India. Environment and Urbanization ASIA 8 (1): 105–19. doi: 10.1177/0975425316683866.

- Jain, M. 2018. Contemporary urbanization as unregulated growth in India: The story of census towns. Cities 73 (March): 117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.10.017.

- Jedwab, R., and Vollrath, D. 2015. Urbanization without growth in historical perspective. Explorations in Economic History 58 (October): 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eeh.2015.09.002.

- Jodhka, S., and Kumar, A. 2017. Non-farm economy in Madhubani, Bihar. Economic and Political Weekly 52 (25–26): 14–24.

- Keil, R. 2018. Extended urbanization, “disjunct fragments” and global suburbanisms. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (3): 494–511. doi: 10.1177/0263775817749594.

- Keyes, C. 2012. ‘Cosmopolitan’ villagers and populist democracy in Thailand. South East Asia Research 20 (3): 343–60. doi: 10.5367/sear.2012.0109.

- Kundu, A. 2014. Exclusionary growth, poverty and India’s emerging urban structure. Social Change 44 (4): 541–66. doi: 10.1177/0049085714548538.

- Lefebvre, H. 1970. La révolution urbaine [The urban revolution]. Paris: Gallimard.

- McFarlane, C., and Robinson, J. 2012. Introduction—Experiments in comparative urbanism. Urban Geography 33 (6): 765–73. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.33.6.765.

- Mehrotra, S., Parida, J., Sinha, S., and Gandhi, A. 2014. Explaining employment trends in the Indian economy: 1993–94 to 2011–12. Economic and Political Weekly 49 (32): 49–57.

- Mehta, N. 2018. Census towns in Gujarat: Economic, social and environmental effects of rural transformation. In Rural transformation in the post liberalization period in Gujarat: Economic and social consequences, ed. N. Mehta, 197–229. Singapore: Springer.

- Mitra, A., and Tripathi, S. 2021. Rural non-farm sector: Revisiting the census towns. Environment and Urbanization ASIA 12 (1): 148–55. doi: 10.1177/0975425321990324.

- Mondal, B., and Samanta, G. 2021. Blurring rural–urban boundaries through commuting. In Mobilities in India: The experience of suburban rail commuting, ed. B. Mondal and G. Samanta, 57–71. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Monte-Mór, R. L. 2014. Extended urbanization and settlement patterns: An environmental approach. In Implosions/explosions: Towards a study of planetary urbanization, ed. N. Brenner, 109–20. Berlin, Germany: Jovis.

- Mukhopadhyay, P., Zérah, M. H., and Denis, E. 2020. Subaltern urbanization: Indian insights for urban theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44 (4): 582–98. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12917.

- Murphy, J. T., and Carmody, P. R. 2019. Generative urbanization in Africa? A sociotechnical systems view of Tanzania’s urban transition. Urban Geography 40 (1): 128–57. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2018.1500249.

- Nayyar, G., and Kim, K. Y. 2018. India’s internal labor migration paradox: The statistical and the real. World Bank’s Policy Research Working Paper 8356. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Nijman, J. 2007. Introduction: Comparative urbanism. Urban Geography 28 (1): 1–6. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.28.1.1.

- Nijman, J. 2015a. The theoretical imperative of comparative urbanism: A commentary on ‘cities beyond compare?’ by Jamie Peck. Regional Studies 49 (1): 183–86. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.986908.

- Nijman, J. 2015b. India’s urban future: Views from the slum. American Behavioral Scientist 59 (3): 406–23. doi: 10.1177/0002764214550304.

- Parnell, S., and Robinson, J. 2012. (Re)theorizing cities from the Global South: Looking beyond neoliberalism. Urban Geography 33 (4): 593–617. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.33.4.593.

- Peake, L., Patrick, D., Reddy, R. N., Sarp Tanyildiz, G., Ruddick, S., and Tchoukaleyska, R. 2018. Placing planetary urbanization in other fields of vision. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36 (3): 374–86. doi: 10.1177/0263775818775198.

- Peck, J. 2015. Cities beyond compare? Regional Studies 49 (1): 160–82. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.980801.

- Pradhan, K. C. 2017. Unacknowledged urbanisation: The new census towns in India. In Subaltern urbanisation in India: An introduction to the dynamics of ordinary towns, ed. E. Denis and M. H. Zérah, 39–66. New Dehli: Springer India.

- Rajan, S. I., and Sumeetha, M., ed. 2019. Handbook of internal migration in India. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Renaud, B. M. 1979. National urbanization policies in developing countries. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Rigg, J., Salamanca, A., and Parnwell, M. 2012. Joining the dots of agrarian change in Asia: A 25 year view from Thailand. World Development 40 (7): 1469–81. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.03.001.

- Robinson, J. 2006. Ordinary cities: Between modernity and development. New York: Routledge.

- Roy, A. 2005. Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association 71 (2): 147–58. doi: 10.1080/01944360508976689.

- Roy, A. 2009. Why India cannot plan its cities: Informality, insurgence and the idiom of urbanization: Planning Theory 8 (1): 76–87. doi: 10.1177/1473095208099299.

- Roy, K., and Samanta, G. 2018. Spread effects vs. localised growth: The case of census towns in Murshidabad district. Space and Culture, India 6 (3): 97–109.

- Sainath, P. 2011. Census findings point to decade of rural distress. The Hindu, September 25, 2011. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/columns/sainath/census-findings-point-to-decade-of-rural-distress/article2484996.ece.

- Schmid, C., Karaman, O., Hanakata, N., Kallenberger, P., Kockelkorn, A., Sawyer, L., Streule, M., and Wong, K. 2018. Towards a new vocabulary of urbanisation processes: A comparative approach. Urban Studies 55 (1): 19–52. doi: 10.1177/0042098017739750.

- Scott, A. J. 2022. The constitution of the city and the critique of critical urban theory. Urban Studies 59 (6): 1105–29. doi: 10.1177/00420980211011028.

- Scott, A., and Storper, M. 2015. The nature of cities: The scope and limits of urban theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (1): 1–15. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12134.

- Shaw, A. 2019. Urban growth and change in post-liberalized India: Small town dynamics. Journal of Urban and Regional Studies on Contemporary India 6 (1): 1–14.

- Sheppard, E., Leitner, H., and Maringanti, A. 2013. Provincializing Global Urbanism: A Manifesto. Urban Geography 34 (7): 893–900. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2013.807977.

- Simone, A. 2004. People as infrastructure: intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture 16 (3): 407–29. doi: 10.1215/08992363-16-3-407.

- Simone, A. 2020. Cities of the Global South. Annual Review of Sociology 46 (1): 603–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054602.

- Simone, A. 2021. Ritornello: “People as Infrastructure.” Urban Geography 42 (9): 1341–48. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2021.1894397.

- Sircar, S. 2017. ‘Census towns’ in India and what it means to be ‘urban’: Competing epistemologies and potential new approaches. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 38 (2): 229–44. doi: 10.1111/sjtg.12193.

- Spivak, G. 1988. Can the subaltern speak? In Marxism and the interpretation of culture, ed. C. Nelson and L. Grossberg, 271–316. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Stark, O. 1991. The migration of labor. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

- Taylor, E. J. 1999. The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration 37 (1): 63–88. doi: 10.1111/1468-2435.00066.

- Thomas, J. J. 2012. India’s labour market during the 2000s. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (51): 39–51.

- Tumbe, C. 2018. India moving: A history of migration. Gurgaon: Penguin Random House India.

- United Nations. 2014. World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision. New York: United Nations.

- United Nations 2019. International migrants stock, online data. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp.

- van Duijne, R. J., Choithani, C., and Pfeffer, K. 2020. New urban geographies of West Bengal, East India. Journal of Maps 16 (1): 172–83. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2020.1819899.

- van Duijne, R. J., and Nijman, J. 2019. India’s emergent urban formations. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (6): 1978–98. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2019.1587285.

- van Meeteren, M., Bassens, D., and Derudder, B. 2016. Doing global urban studies: On the need for engaged pluralism, frame switching, and methodological cross-fertilization. Dialogues in Human Geography 6 (3): 296–301. doi: 10.1177/2043820616676653.

- Ward, K. 2008. Editorial—Toward a comparative (re)turn in urban studies? Some reflections. Urban Geography 29 (5): 405–410. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.29.5.405.

- World Bank. 2009. World development report: Reshaping economic geography. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5991.

- World Bank 2021. World Bank data on employment in agriculture in India. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS.