Abstract

A multitude of global challenges that society grapples with, including climate change, social injustices, and economic disparities, persist largely due to the shortcomings of effectively responding to complex systems. In this article, we consider adopting systems literacy as a comprehensive educational approach to navigate in complex systems. We advocate for a systems literacy pedagogy that employs an affective-relational-cognitive (ARC) framework for learning, emphasizing active engagement and intervention in the world. The concept of systems beings is rooted in both ontological education and systems literacy, and we propose the ARC framework as both a pedagogical theory and practice to further understand and engage with it. This is further explored through an educational example of a transdisciplinary doctoral pilot project focused on the climate emergency.

Responding to a complex world

Numerous global challenges, ranging from climate change and pandemics to global food supply and economic disparities, stem from society’s struggle to effectively respond to complex systems (Senge, Citation2006). It is becoming increasingly clear that educating society to function within complex systems provides a compelling alternative to the linear, reductionist approaches to inquiry that have dominated science and educational research for more than a century (Davis & Sumara, Citation2014). And yet, systems approaches have been slow to influence normative education practices (Dreier et al., Citation2019; Shulhina & Dąbrowska, Citation2022). Responding to multiplying global polycrises requires holistic knowledge of, experiences with, and, ultimately, the shifting of systems, which are interconnected elements working together and whose properties emerge from these relationships.

As two researchers from historically disparate disciplines in education and engineering, and who both work in climate and sustainability education, we were provoked into exploring complex systems more deeply after co-leading a collaborative transdisciplinary doctoral pilot project at our university (Ramachandran et al., Citation2024). This pilot project (discussed later) displayed the unpredictable messiness of process-oriented education through the aim of co-creating knowledge inside and outside of academia to deal with the complexity of climate change. What we observed in our reflective practice is that the real and imagined worlds we inhabit as beings are co-constructed, and evince paradoxes and contradictions that often fall outside of normative educational models. We initially inquired: how do we educate ourselves to work in complex systems? Through further iterations, the question ultimately became: how might we theorize a type of action-oriented pedagogy that could also encourage engagement in the world (i.e. being-in-the-world)? Guided by this question, we explore in this article a literacy approach that could serve as a theoretical foundation for understanding existence or being with/in systems.Footnote1

Systems literacy, as an applied and theoretical learning of systems, generates meaning through, in, and among interconnected and complex systems that often bring uncertainties, paradoxes, and contradictions. Developing a literacy of systems perspectives offers a holistic orientation to experience and imagine reflexive education practices. Because literacy education has evolved historically through multiple phases of learning and experience (Tierney & Pearson, Citation2021), literacy has become an integrated praxis (practice and theory) used in diverse contexts moving beyond narrower definitions or applications (Lee et al., Citation2022). Scholars explore what literacy is, does, and becomes as actionable and emerging processes of meaning-making (e.g. The New London Group, Citation1996; Vasquez et al., Citation2019), including interpretation, creation, communication, and identification (Montoya, Citation2018).

In complexity-orientated frames, systems literacy can be understood as the capacity to identify, interpret, co-create, relate to, and communicate about how systems work, transcending both the fragmentation of siloed disciplines and reductive cognitive models of normative educational inquiry (Cochran-Smith et al., Citation2014; Crowell, Citation1992). Systems literacy has the potential to shift reductive worldviews (i.e. everything is separate and independent) to interconnected, non-linear, and relational paradigms.

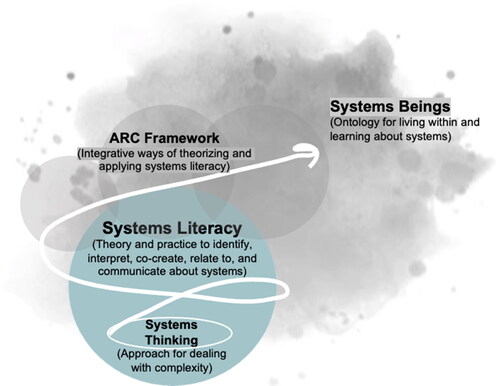

In this article, our focus is on embracing systems literacy as a comprehensive educational approach for understanding and navigating complex systems. Discussions Dialogue involving Western and Indigenous scholars exploring systems approaches, as exemplified in Goodchild (Citation2021), have spurred the evolution and broadening of prior concepts related to systems thinking. In response to these developments, we are advocating for a systems literacy pedagogy using an affective-relational-cognitive (ARC) framework for learning. This approach is action-oriented, encouraging active engagement with and intervention in the world—i.e. being with/in systems. The term systems beings encapsulates the multifaceted experience and awareness of existing in and learning about systems. The concept is rooted in both ontological education and systems literacy, and we use the ARC framework as both a pedagogical theory and practice to further understand and engage with it. To consolidate these ideas, we synthesize them into the concept of systems beings and illustrate its application through a brief case study example to conclude.

Transitioning from systems thinking to literacy

Complex systems theory is considered an orientation for understanding complex phenomena (Kuhn, Citation2008), and involves the interconnected, unpredictable, and interdependent factors and relationships of various systems. A ‘literacy of complexity’, as Kincheloe and Berry (Citation2004, p. 24) pointed out, offers a pathway into the multiple layers of identities, social actors, and contexts humans must negotiate when living in the world. Expanding from a tradition of examining complex systems in the realm of science, there is a rising trend in researchers looking at complexity within the field of education (Andreotti, Citation2021; Davis & Sumara, Citation2014; Drake et al., Citation2017; Guile & Wilde, Citation2022; Lancaster, Citation2013; Mason, Citation2013; Morrison, Citation2013). Systems thinking and theory emerged historically as a way to understand, manage, and respond to complexity (Capra & Luisi, Citation2014; Merali & Allen, Citation2011; von Bertalanffy, Citation1968). Midgley and Rajagopalan (Citation2021) demonstrated how systems thinking within Euro-centric scholarship arose out of the limitations of traditional and scientific methods in addressing environmental, social, and organizational issues. While reductive scientific methods resulted in restrictive and arbitrary disciplinary boundaries (Capra & Luisi, Citation2014; von Bertalanffy, Citation1968), they also often reflected anthropocentric, patriarchal, and colonial values.

Such critiques echo an ever-growing chorus of Indigenous scholars, among others, calling out similar shortcomings of systems thinking (Cajete, Citation2000; Kimmerer, Citation2002; Little Bear, Citation2009; Ritskes, Citation2014; Wilson, Citation2008). In a cross-cultural dialogue between Western and Indigenous systems scholars (i.e. Senge, Scharmer, Longboat, and others) about how to sense and shift systems, Goodchild (Citation2021) noted that Western approaches tend to focus on abstraction without lived experience, privileging thinking over embodied forms of knowledge, or a ‘separation of knowing and sensing’ (pp. 91–92). Terra and Passador (Citation2015) also highlighted the epistemological limitations of systems thinking and expanded the possibility of describing richly interconnected systems through a phenomenological perspective.

These critiques illustrate how systems thinking alone may not be enough: a multifaceted systems literacy approach is becoming increasingly vital. Using systems literacy as an educational intervention and social practice provides a capacity to examine complex socio-ecological issues through the lens of processes, relationships, and interrelationships (Nguyen et al., Citation2023). Systems literacy supports this un/learning—individually and collaboratively—through iterative, reflexive, non-linear processes of grounding, questioning, broadening, integrating, and developing an embodied and relational understandings (Steele, Citation2016).

At the same time, most systems literacy literature has emerged from practice in leadership and decision making (Cremene, Citation2022; Dubberly, Citation2014), science (Goede, Citation2020), and practical application toolkits (Silverman, Citation2017), and remains an underdeveloped field of theory and practice compared to systems thinking and theory. As systems literacy invites a multidimensional understanding of interdependent relationships, particularly how systems influence us (e.g. perceptions, beliefs, values, etc.) and how we influence systems (Edson et al., Citation2017; Goodchild, Citation2022), there is an opportunity to ground systems literacy through a theoretical framework that both builds on and extends from previous scholarship.

Ontological beings

Drawing on systems thinking and theory developed over the past century, variations on the concept of being in systems has been considered previously through approaches such as systems education design (Banathy, Citation1991), philosophy (Laszlo, Citation1972), and leadership (Laszlo, Citation2012). While links between systems literacy and beings are less connected, notions of systems beings (simultaneously plural and singular) invoke deeper epistemic and ontological questions around the nature of the world, including the knowledge of and interactive relationship with the world. In this section, we delve deeper into the rationale for incorporating beings as a crucial link and extension of systems literacy, offering context to the ARC framework.

Acknowledging the need for further engagement with complex systems, we use an ontological framework that invites not only the doing of systems work, but also awareness and understanding as a holistic process of being with/in systems. The concept of systems beings originates from the understanding that we are integral components of the systems we explore, particularly in the realm of knowledge utilization and application (epistemology). This orientation, related to the existence, reality, and the nature of being in systems, embodies a sense of (self-)reflexivity. The intention is to de-universalize various perspectives, encouraging us to consider interpretations and experiences through diverse worldviews and ways of being or perceiving different facets of reality (ontology). Put simply, systems beings can be considered as an ontology that acknowledges our fundamental interconnected nature with/in systems.

Ontological approaches explore the nature of being or existence (Crotty, Citation2003), particularly in relation to knowledge production with larger processes and relationships (Kincheloe & Berry, Citation2004). The ontological turn in education, as discussed by scholars such as Dall’Alba and Barnacle (Citation2007), Zembylas (Citation2017), and Carusi and Szkudlarek (Citation2020), has opened conversations about the nature of reality within educational frameworks. The traditional view of one world, or even various worldviews, has evolved into a recognition of multiple worlds (Paleček & Risjord, Citation2012). This shift implies that people engage with various ontological paradigms, participating in multiple ways of understanding reality, rather than adhering to a single dominant paradigm.

The ontological turn allows for alternative paths forward and with the aim to reconceptualize learning (Zembylas, Citation2017). According to Thomson (Citation2016), ontological education involves learning how to ‘respond’ to the concept of ‘being.’ It is described as a ‘phenomenologically dynamic dimension’ that goes beyond the capacity to conceptualize ‘language and meaning without being fully captured within them’ (p. 847). Ontological education, as a way of framing being with/in systems, provides contexts to understand how embedded and entwined humans and more-than-humans are in the socio-ecological systems of multiple worlds (Little Bear, Citation2009).

Scholars have argued that the challenges facing higher education are largely ontological (Andreotti, Citation2021; Dall’Alba & Barnacle, Citation2007). Such inquiries not only involve educational praxes, but are also about the nature of learning and how various embodied entanglements of material and discursive realities may affect multifaceted learning (Zembylas, Citation2017). In conventional higher education programs, for example, the continued focus on the intellect overlooks the role of the lived body in embodied ways that highlight the interdependence of knowing and being. Educating as ways-of-being treats knowledge as created, embodied, and enacted (Dall’Alba & Barnacle, Citation2007). As Thomson (Citation2001) pointed out, with regards to Heidegger’s ontological questions about education through a phenomenological lens, the notion of beings transforms learning about the worlds around us, also known as being-in-the-world (Heidegger, Citation1962). The ways we know about the world are dependent upon our histories of being, such as everyday practices, projects, and activities, thus highlighting the interdependence of ontology and epistemology (Dall’Alba & Barnacle, Citation2007).

The field of phenomenology and education can inform how to situate ontological dimensions of education (Van der Mescht, Citation2004), as it clarifies learners’ sense-making and leads to new insights into the processes of learning across multiple worlds. In these conditions of education, a question arises as to how beings are in process, and therefore adapting to changing circumstances, rather than merely an inert or fixed existence in systems. As a critical practice of education, Freire (Citation1968/2005) described ‘beings in the process of becoming’ (p. 84), or beings in an ever-changing existence. This notion of beings invokes the Bergsonian meaning of ‘duration’ , emphasizing the interplay of oppositions between and among permanence and change (Freire, Citation1968/2005, p. 84).

Such an incompleteness or state of constant un/learning, of the uncertainty of im/permanence, is the very act of being educated as an ongoing process. While acknowledging being in constant process without a sense of arrival or conclusion, it also implies already being-in-the-world without the tension of having to arrive or complete. Being in systems is something that always exists, whether people are aware of it or not. Similarly, people are ecological beings because we are part of the Earth’s ecological systems as human species (Morton, Citation2018). It is important to emphasize that as beings living in and affecting systems, our sense of knowing is embodied, enacted, and in relation to other systems, which will be outlined in the next section as a way to further understand ways-of-being as a part of systems literacy.

ARC framework

We adopted and adapted a framework from previous scholarship (Andreotti, Citation2021; Andreotti et al., Citation2014; Gable et al., Citation2005; Murray, Citation2012), what we are referring to as affective-relational-cognitive (ARC), that underscores the integrative ways of theorizing systems literacy and developing an awareness of being with/in systems through various knowledges and perspectives. While recognizing the dynamic nature of systems, the ARC framework embodies the intricate aspects of systems change as actionable and emerging literacy processes (Vasquez et al., Citation2019). It provides an approach within ontological education models by offering holistic and multifaceted ways of learning through and within bodies, minds, and relationships. depicts a dynamic process of weaving the affective-relational-cognitive aspects of awareness through ontological and epistemological diversity within systems.

Affective

Affect, as a critical approach to study feelings, bodies, and sensations that draws on phenomenology, is a useful way to consider embodied forms of learning (Ehret & Rowsell, Citation2021; Epstein, Citation2019; Massumi, Citation1995; Merleau-Ponty, Citation1962/1945; Seigworth & Gregg, Citation2010). Affective approaches promote shifts from social and educational emphases of cognitive (intellectual) capacities as singular mediums to navigate knowledge and experiences to the uncertain domains of complex systems involving paradoxes or contradictions (Machado de Oliveira, Citation2021). An embodied engagement to the world allows new ideas to emerge beyond formalized knowledge production (Dreyfus, Citation1999).

Traversing many disciplines, the concept of affect can seem nebulous, and its applications vary (Epstein, Citation2019; Massumi, Citation1995; Schaefer, Citation2019). Seigworth and Gregg (Citation2010) considered a way to measure the ‘body’s capacity to affect and be affected’ (p. 2), arising out of the ‘in-between-ness’ of action and being acted upon, whether among human, more-than-human, part-body, or otherwise (p. 1). The simultaneity of affect—both in action and being acted upon—highlights how bodies are constantly in relation to their surroundings, which include systems.

While emotions are channelled through affective responses, affect and emotion are not synonymous. If affect is considered as a form of intensity, as Massumi (Citation1995) suggested, then affect is ‘unqualified’ and ‘not ownable or recognizable’ as an emotion (p. 88). Emotion might be consciously owned and recognized, whereas affect can be unconsciously acted upon and mediated by our bodies. Considering the body as a medium for knowledge invites multilayered engagements with not only physical sensation, according to Merleau-Ponty (Citation1962/1945), but also the ‘lived body’ (p. 93) of experience as a source of ambiguity and uncertainty. Such ambiguities of the lived body manifest as intensities, referring back to Massumi (Citation1995), that represent unrecognizable sensations or experiences that may seem like emotions but are also outside of such ownable feelings. We might, for example, experience many intensities throughout our daily lives, and due to a commonly experienced unconscious relationship to our bodily reactions, the affective experiences occupy the ambiguous in-between-ness of knowing and being.

Through movement one can interpret and communicate with the body as a governing vessel of knowing and being. This form of embodied awareness enhances systems literacy in the ways it makes possible the spaces to experience existence across multiple worlds (Paleček & Risjord, Citation2012)—what Massumi (Citation2015), drawing on Deleuze and Guattari, calls ‘transversal’ (p. 107), or cutting across the usual categories of subjectivity and objectivity. As a result, affective approaches to being in systems enable a multifaceted literacy in how and what we know in the context to other parts of systems.

Relational

Relational approaches are fundamental to existence in complex systems (Little Bear, Citation2009, Lancaster, Citation2013; Mason, Citation2013), largely because systems are the relationships between the parts of the whole. To understand interdependence is to see relationships (Capra & Luisi, Citation2014). Relational dynamics in a system are the systems themselves. Connectedness, for instance, requires distributed knowledge circulated through systems (Morrison, Citation2013). Consciously acknowledging the interconnected nature of existence not only de-centres reductive individualism as a primary ontology of social organization; it also expands the capacities to apply affective and cognitive ways of being. We, as systems beings, are part of smaller organized systems, such as communities or groups, and part of the larger organisms of the land or planet (GTDF, n.d.).

Diving deeper into the embodied learning of being in these systems, Gergen (Citation2009) considered how relationships co-create meaning, thereby fostering conditions to engage in multiple worlds. Individual reason, for instance, is developed from the paradigm of individuality. Education has historically been an individualistic enterprise, focusing on monological over dialogical perspectives—or, the difference between I know and let us explore (Gergen, Citation2009). Dialogical training—exploring and sharing the meaning-making experience together—buttresses relational dynamics between and with/in systems. Rather than being a by-product of the collaborative co-action in relationship, it is the source of it.

In this sense, our interconnections and ways of making meaning depend upon relationships of all kinds—through people, language, experience, interdependence, etc. As De Jaegher and Di Paolo (Citation2007) asserted, ‘Sense-making is a relation and affect-laden process’ (p. 488). Relational dynamics are the frameworks of systems: humans and more-than-humans are part of these complex systems, and these relationships to and experiences with each other co-create meaning in systems.

Cognitive

Cognition is the mental ability to acquire knowledge through various forms of thinking, memory, rationality, and experience. Despite efforts to isolate cognition as a primary mode of intelligence, it also overlaps with and relies on ways of feeling, sensing, and relating to respondent parts of systems. Through our cognitive associations we can critically analyze beliefs and assumptions, acquire knowledge in context to other knowledge systems, or realize that rational knowledge is one limited approach among the interdependence of epistemology and ontology.

Salner (Citation1986) emphasized the development of cognition, moving from dualism to multiplicity and contextual knowledge. The notion of ‘integrating the inquirer into the inquiry’ (i.e. being both the observed and observer) draws on cultivating metacognition in being aware of one’s perception, position, and understanding of knowledge (Montuori, Citation2022, p. 174). This awareness can support thinking about thinking (i.e. forms of metacognition), and allow inquirers to be open to ways that we construct and are constructed by knowledge. Ultimately, cognitive approaches support explorations about what and how we know, as well as the organization of knowledge underlying knowing.

In isolation, as a privileged knowledge system, cognitive approaches remain limited in how they can engage, understand, and contend with complexity. Cognition can be holistic, thereby de-centring the individual as a cognitive vehicle for knowledge production and translation. The aim is to broaden prevailing approaches to cognition, as an integral element of ARC, by incorporating expansive ways of thinking/knowing/learning/being in systems.

Systems beings in action

In the following section, we provide an educational example to illustrate systems beings as an action-orientated practice that invites engagement with the world. As depicted in , the approach to systems beings draws on previously mentioned elements. This process is facilitated through systems literacy, which encapsulates the ARC framework, and informed by ontological educational approaches of cultivating multiple worlds to learning in systems.

To illustrate this framework, we draw on a Transdisciplinary (TD) Collaborative PhD Pilot program model focused on the climate emergency at the University of British Columbia, Canada.Footnote2 TD research often includes various disciplines dissolving into one another to create new forms of knowledge, adaptive, and collaborative team learning, and a cooperation between academia and society. This occurred in two sequential periods involving two different cohorts (faculty and students), which were set-up as a design-based research process conducting meta-analyses and designing for a future doctoral program. The first cohort was given a task to co-design aspects of the TD pilot program (more details in Ramachandran et al., Citation2024), while the second cohort engaged in TD research with external stakeholders for one year.

Preparing a new generation of students to engage with and navigate complex systems amid global challenges requires providing them with transformative forms of learning. This includes fostering transdisciplinary competencies and expertise, as highlighted by Drake and Reid (Citation2021), along with the ability to navigate uncertainties and adapt to rapid changes (Dias, Citation2015). As documented (Ramachandran et al., Citation2024), we have experimented with focusing on the process and exercising our capacity around ambiguity and uncertainty through open-ended tasks as collaborators. We also applied the ARC framework as a way to assist students in the process of developing an awareness and practice of working with/in systems.

Bringing together students from diverse disciplines, participants were given opportunities to not only enhance their cognitive development, but also to experience multiple worlds (Paleček & Risjord, Citation2012). This required the ability to hold different perspectives, and as a result paradoxes and contradictions that require non-cognitive forms of learning, amidst multiple ontological approaches of embodied and relational learning around a collective topic. Our intention was to create a space for ‘letting learn’ to occur where ‘integration of knowing, acting and being’ unfolded (Dall’Alba & Barnacle, Citation2007, p. 688).

To demonstrate the collaboration of multiple disciplines and perspectives in co-creating and experiencing being in systems, we brought in a bag of percussion instruments. Participants were invited to choose an instrument from the collection on the floor. The exercise unfolded in three parts. Initially, participants played together in unison, following a simple rhythm (e.g. Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You’). In the next phase, each participant played their instrument independently without regard for others in the room. The final part involved improvisation, encouraging participants to listen to each other and explore creative dimensions of the generated sound collectively. These phases, representing unity, chaos, and improvisation, served as examples of navigating the uncertainties and paradoxes of complexity with others (Morin, Citation2001). They also illustrated the interconnective elements of the ARC framework: feeling as affective, thinking as cognitive, and listening as relating. During the reflective dialogue that followed, participants shared their experiences of actively listening to synchronize with others and embodying the nuances of relating to other participants, whether in harmony or dissonance. Framing the entire experience through the lens of ARC facilitated the development of awareness and the lived experience of being in systems.

In teaching complexity, Kuhn et al. (Citation2011) developed metaphors to allow learners to build epistemic cognition and awareness. We used the metaphor of conditioning and cultivating the soil where learning can emerge. By focusing on cultivating the soil, students could participate in the process of being without the expectation of completion or outcomes. To tend a regenerative garden, for instance, the soil needs to be reconditioned overtime. Often, however, the focus is on what to grow and how quickly this growth may occur. By focusing more on the process—i.e. conditioning of the soil, rather than the output of the garden—we have collectively experienced being as a way to engage with/in complex systems. Morin (Citation2001) similarly proposed that instead of solely examining the outcomes of a system, delving into the underlying paradigm (akin to cultivating soil) that produces those outcomes can open the door to the potential for constructing new paradigms.

During one of the sessions, we asked participants to imagine a world in a climate emergency and how these images affected us.Footnote3 We walked silently for several minutes in a circle around a chair placed in the middle, with the chair representing a climate image. As we walked, we focused on the climate image and allowed ourselves to move beyond the ‘self’ or the ‘I’ and attempted to feel the connection to others in the circle. We then shared our affective responses to these climate images (without defining emotions) through a metaphorical object (i.e. a person, tree, polar bear, etc.), allowing our embodied experiences in response to that object to emerge. This invited a co-experience of moving between and beyond the self in a reflexive way, as well as experiencing the affective state, or intensity (Massumi, Citation1995), that emerged in our bodies as we acted out and upon the imagined object representing climate emergency. This experience provided spaces to occupy the ambiguous in-between-ness of knowing and being, represented in through the ARC framework.

Using phenomenology to understand affective experiences in educational settings, Thorburn and Stolz (Citation2021) stated, ‘the reversible process of moving and being observed moving is part of embodied and reflexive agency, where bodily activities and language interchange with each other and where there is a shared appreciation of the connectedness of our intersubjective being’ (p. 101). The participants shifted from understanding and imagining climate emergency solely through cognition to sharing embodied experiences of an object between the self and others in a relational process of making meaning together. Through reflecting and sharing collective experiences with everyone, relational understanding and learning emerged. The participants’ collective ARC experiences and subsequent reflections have shifted their awareness of and response to being in systems, as shown in . A part of this exercise is now formed into a workshop facilitation where participants are invited into reflexive scenarios and presented multiple ways of facing elements of the climate crisis to reflect on their own biases, experiences, and/or challenges.

Another key part of this TD model is how our work with external stakeholders also allowed us to engage with multidimensional perspectives, values, and needs—i.e. multiple worlds that can translate the ARC framework into action-oriented processes. We often use the embodied and relational metaphor of dancing, inspired by Meadows (Citation2001), as a way of capturing the integrated process of being in systems with the external stakeholders, uncovering assumptions, noticing the self and the collective, and relinquishing the notion of control or outcomes. Because it is improbable to govern or fix systems, we can instead dance with them (Meadows, Citation2001). Dancing with systems implies an act of play, while it also requires attention, practice, and stamina. The uncertainties of complex systems allow the dance to continue in a constant state of un/learning.

As beings in systems, an ontological shift in systems literacy practices increases awareness and action. The exercise of co-creating meaning and knowledge with non-academic partners has allowed us to re-examine where and how these learnings can reside and ways to train learners as actionable participants. It also informed us where to communicate with them in scholarly platforms, thereby leading us to develop a pedagogy that might be useful for those attempting to understand their ability as beings to dance with/in systems.

In this educational context, the use of the ARC framework facilitated access to and experience of multiple ontological worlds. This approach involved fostering meaning through relationships, embracing embodied learning (e.g. through dance, movement, and music), and expanding cognitive approaches by analyzing beliefs and assumptions. The ARC framework enhances building the capacity of being in systems, providing greater opportunities to navigate uncertainty and ambiguity, especially when encountering shifting paradigms. As an ongoing awareness of being in systems, we continue to co-create these opportunities to experiment in academic settings in shaping ARC within systems literacy. To that end, we have formed and co-lead an educational research Systems Beings Lab as an open-ended process of exploration.Footnote4

Conclusion

In response to the increasing complexities in the world, embracing systems beings as an ontology for living within and learning about systems offers an educational approach grounded in systems literacy. This approach facilitates alternative ways of knowing, being, and learning, co-creating possible futures. Utilizing the ARC framework, we have conceptualized systems literacy as an action-oriented pedagogy, engaging with epistemological diversity and ontological learning as systems beings. This perspective acknowledges that we are inter-operating beings, intricately entwined affectively, relationally, and cognitively, in constant interaction with systems, including how these systems act upon and shape us.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Vanessa Andreotti for providing the workshop on embodied climate engagement, and for her collaborative research that supported some of the framing in this paper. The authors also wish to thank Jennifer Cutbill for help with the design of both figures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Derek Gladwin

Derek Gladwin (Associate Professor, Language and Literacy Education) and Naoko Ellis (Full Professor, Chemical and Biological Engineering) are a collaborative team and founding members of the Systems Beings Lab at the University of British Columbia. They complement their disciplinary backgrounds within the nexus of environmental education, blending the socio-cultural with STEM and technical approaches, to provide holistic and transdisciplinary perspectives. They have published articles and books on topics such as energy transition, transdisciplinary education, carbon capture and conversion technology, and complexity and storytelling. They also give talks and workshops and consult with global partners on educational design (dneducationdesign.ca).

Notes

1 We use with/in throughout to signify both working with and in systems simultaneously.

3 This activity was adapted from an embodied workshop on climate emergency for our PhD Cohort participants facilitated by Dr. Vanessa Andreotti at the University of British Columbia.

References

- Andreotti, V. O. (2021). Depth education and the possibility of GCE otherwise. Globalisation, Societies, and Education, 19(4), 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1904214

- Andreotti, V., Fa’afoi, A., Sitomaniemi-San, J., & Ahenakew, C. (2014). Cognition, affect and relationality: Experiences of student teachers in a course on multiculturalism in primary teacher education in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Race Ethnicity and Education, 17(5), 706–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.759920

- Banathy, B. H. (1991). Systems design of education: A journey to create the future. Educational Technology.

- Cajete, G. (2000). Native science: Natural laws of interdependence. Clear Light Publishers.

- Capra, F., & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Cambridge University Press.

- Carusi, T. F., & Szkudlarek, T. (2020). Education is society … and there is no society: The ontological turn of education. Policy Futures in Education, 18(7), 907–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320933018

- Cochran-Smith, M., Ell, F., Ludlow, L., Grudnoff, L., & Aitken, G. (2014). The challenge and promise of complexity theory for teacher education research. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 116(4), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411600407

- Cremene, L. (2022). Complex systems literacy: Social dilemmas – the setup for managerial decision-making in a complex world. In A. Taylor (Ed.), Rethinking Leadership for a Green World (pp. 145–175). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003190820

- Crotty, M. (2003). The Foundations of social research: Meaning and perspectives in the research process. Sage.

- Crowell, F. A. (1992). Systems literacy and the literate design of educational systems. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth Annual Meeting for the International Society for the System Sciences (ISSS), (pp. 12–17).

- Dall’Alba, G., & Barnacle, R. (2007). An ontological turn for higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 32(6), 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701685130

- Davis, B., & Sumara, D. (2014). Complexity and education: Inquiries into learning, teaching, and research. Routledge.

- De Jaegher, H., & Di Paolo, E. (2007). Participatory sense-making: An enactive approach to social cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 6(4), 485–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-007-9076-9

- Dias, B. D. (2015). Beyond sustainability–biophilic and regenerative design in architecture. European Scientific Journal, 11(9), 147–158.

- Drake, J., Kupers, R., & Hipkins, R. (2017). Complexity – a big idea for education? International School: Is, 19(2), 28–31.

- Drake, S., & Reid, J. (2021). Thinking now: Transdisciplinary thinking as a disposition. Academia Letters, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL387

- Dreier, L., Nabarro, D., & Nelson, J. (2019). Systems leadership for sustainable development: Strategies for achieving systemic change. Corporate Responsibility Initiative, Harvard Kennedy School, 1–48. https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/mrcbg/publications/fwp/crisept2019

- Dreyfus, H. L. (1999). The primacy of phenomenology over logical analysis: A critique of Searle. Philosophical Topics, 27(2), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.5840/philtopics19992722

- Dubberly, H. (2014). A systems literacy manifesto. In Proceedings of RSD3, Third Symposium of Relating Systems Thinking to Design, 15-17 Oct 2014, Oslo, Norway. http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/2058/

- Edson, M., Metcalf, G., Tuddenham, P., and Chroust (Eds.) (2017). Systems literacy – Proceedings of the eighteenth IFSR conversation 2016. Books on Demand.

- Ehret, C., & Rowsell, J. (2021). Literacy, affect, and uncontrollability. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(2), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.387

- Epstein, I. (2019). Affect theory and comparative education discourse: Essays on fear and loathing in response to global educational policy and practice. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Freire, P. (1968/2005). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Transby Bergman Ramos, Continuum.

- Gable, R. A., Hester, P. P., Hester, L. R., Hendrickson, J. M., & Sze, S. (2005). Cognitive, affective, and relational dimensions of middle school students: Implications for improving discipline and instruction. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 79(1), 40–44. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.79.1.40-44

- Gergen, K. (2009). The relational being: Beyond Self and Community. Oxford University Press.

- Goede, R. (2020). Nature’s enduring patterns: A path to systems literacy. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 37(5), 787–788. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2741

- Goodchild, M. (2021). Relational systems thinking: That’s how change is going to come, from our earth mother. Journal of Awareness-Based Systems Change, 1(1), 75–103. https://doi.org/10.47061/jabsc.v1i1.577

- Goodchild, M. (2022). Relational systems thinking: The Dibaajimowin (story) of re-theorizing “systems thinking” and “complexity science”. Journal of Awareness-Based Systems Change, 2(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.47061/jabsc.v2i1.2027

- GTDF: Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures. (n.d.). GCE Otherwise: In Earth’s CARE dispositions/learning objectives. https://decolonialfutures.net/in-earths-care-dispositions/

- Guile, D., & Wilde, R. J. (2022). Complexity theory and learning: Less radical than it seems? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2022.2132934

- Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and Time. Translated by J. Macquarrie, SCM Press.

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2002). Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into biological education: A call to action. BioScience, 52(5), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0432:WTEKIB]2.0.CO;2

- Kincheloe, J. L., & Berry, K. S. (2004). Rigour and complexity in educational research: Conceptualizing the bricolage. Open University Press.

- Kuhn, L. (2008). Complexity and educational research: A critical reflection. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(1), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00398.x

- Kuhn, L., Woog, R., & Salner, M. (2011). Utilizing complexity for epistemological development. World Futures, 67(4-5), 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2011.585886

- Lancaster, J. E. (2013). Complexity and relations. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(12), 1264–1275. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2013.763595

- Laszlo, E. (1972). Introduction to systems philosophy: Toward a new paradigm of contemporary thought. Gordon & Breach Science Publishers.

- Laszlo, K. C. (2012). From systems thinking to systems being: The embodiment of evolutionary leadership. Journal of Organisational Transformation & Social Change, 9(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1386/jots.9.2.95_1

- Lee, C., Bailey, C., Burnett, C., & Rowsell, J. (2022). (Eds.) Unsettling literacies: Directions for literacy research in precarious times. Springer.

- Little Bear, L. (2009). Naturalizing indigenous knowledge synthesis paper. Canadian Council on Learning. Aboriginal Learning Knowledge Centre. http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education/21._2009_july_ccl-alkc_leroy_littlebear_naturalizing_indigenous_knowledge-report.pdf

- Machado de Oliveira, V. (2021). Hospicing modernity: Facing humanity’s wrongs and the implications for social activism. North Atlantic Books.

- Mason, M. (2013). What is complexity theory and what are its implications for educational change? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00413.x

- Massumi, B. (1995). The autonomy of affect. Cultural Critique, 31(31), 83–109. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354446

- Massumi, B. (2015). Politics of affect. Wiley.

- Meadows, D. (2001). Dancing with systems. Whole Earth, 106, 58–63.

- Merali, Y., & Allen, P. M. (2011). Complexity and systems thinking. In P. Allen, S. Maguire, & B. McKelvey (Eds.), The Sage handbook of complexity and management (pp. 31–52). SAGE.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962/1945). Phenomenology of perception. Trans. by Colin Smith. Routledge.

- Midgley, G., & Rajagopalan, R. (2021). Critical systems thinking, systemic intervention and beyond. In G.S. Metcalf, K. Kijima, & H. Deguchi (Eds.), Handbook of systems sciences (pp. 107–157). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0720-5

- Montoya, S. (2018). Defining Literacy. UNESCO Institute for Statistics, GAML Fifth Meeting, pp. 1–10. https://gaml.uis.unesco.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/12/4.6.1_07_4.6-defining-literacy.pdf

- Montuori, A. (2022). Integrative transdisciplinarity: Explorations and experiments in creative scholarship. Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science, 13, 161–183. https://doi.org/10.22545/2022/00209

- Morin, E. (2001). Seven complex lessons in education for the future. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

- Morrison, K. (2013). Educational philosophy and the challenge of complexity theory. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00394.x

- Morton, T. (2018). Being ecological. Penguin.

- Murray, T. (2012). Self-knowledge development as a cognitive, affective, relational and spiritual journey. Religion & Education, 39(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15507394.2012.648588

- Nguyen, L.-K.-N., Kumar, C., Jiang, B., & Zimmermann, N. (2023). Implementation of systems thinking in public policy: A systematic review. Systems, 11(2), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11020064

- Paleček, M., & Risjord, M. (2012). Relativism and the ontological turn within anthropology. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 43(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393112463335

- Ramachandran, A., Schwellnus, M., Gladwin, D., Derby-Talbot, R., & Ellis, N. (2024). Cultivating educational adaptability through collaborative transdisciplinary learning spaces. Discover Education, 3(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-023-00084-5

- Ritskes, E. (2014). Leanne Simpson and Glen Coulthard on Dechinta Bush University, Indigenous land-based education and embodied resurgence. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society. https://decolonization.wordpress.com/2014/11/26/leanne-simpson-and-glen-coulthard-on-dechinta-bush-university-indigenous-land-based-education-and-embodied-resurgence/

- Salner, M. (1986). Adult cognitive and epistemological development in systems education. Systems Research, 3(4), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.3850030406

- Schaefer, D. O. (2019). The evolution of affect theory: The humanities, the sciences, and the study of power. Cambridge University Press.

- Seigworth, G. J., & Gregg, M. (2010). An inventory of shimmers. In G.J. Seigworth & M. Gregg (Eds.), Affect theory reader (pp. 1–25). Duke University Press.

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Broadway Business.

- Shulhina, L., & Dąbrowska, A. (2022). A Systems approach to the development of educational standards for fostering personal values. Marketing of Scientific and Research Organizations, 43(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2478/minib-2022-0001

- Silverman, H. (2017). Systems Literacy: A Toolkit for Purposeful Change. The Community Resilience Reader: Essential Resources for an Era of Upheaval, 131–145.

- Steele, C. S. (2016). Education in the age of complexity: Building systems literacy. [Ph.D. Dissertation]. The University of Vermont. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/588/

- Terra, L. A. A., & Passador, J. L. (2015). A phenomenological approach to the study of social systems. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 28(6), 613–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-015-9350-7

- The New London Group. (1996). A Pedagogy of multiliteracies designing social futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Lit Learning (pp. 19–46). Routledge.

- Thomson, I. (2001). Heidegger on ontological education, or: How we become what we are. Inquiry, 44(3), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/002017401316922408

- Thomson, I. (2016). Rethinking education after Heidegger: Teaching learning as ontological response-ability. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 48(8), 846–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1165018

- Thorburn, M., & Stolz, S. A. (2021). Emphasising an embodied phenomenological sense of the self and the social in education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 69(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2020.1796923

- Tierney, R. J., & Pearson, D. P. (2021). History of literacy education: Waves of research and practice. Teachers College Press.

- Van der Mescht, H. (2004). Phenomenology in education: A case study in educational leadership. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 4(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2004.11433887

- Vasquez, V. M., Janks, H., & Comber, B. (2019). Critical literacy as a way of being and doing. Language Arts, 96(5), 300–311. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26779071 https://doi.org/10.58680/la201930093

- von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General system theory: Foundations, development. George Braziller.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood.

- Zembylas, M. (2017). The contribution of the ontological turn in education: Some methodological and political implications. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(14), 1401–1414. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1309636