ABSTRACT

This microhistory of a shoreline place in Thailand details the socio-natural process by which a piece of coastal land came to be recognised as private property by the state. It demonstrates that intimate and long-term attention to specificities of how property comes into being has more explanatory power than synoptic theorisations of accumulation and dispossession. Using ethnography, archives and affective co-narration, this paper probes the shifting ground of water and land to show how the fluidity of water plays a key role in the politics and legal procedures of enclosure, and how fluctuating boundaries become an ambiguous arena for property claims contestations amid entanglements of slippery legal semantics. It argues that the expanded notion of agency in the Anthropocene presents new challenges for thinking about property relations, and that thinking from a shoreline place of shifting water-land boundaries engenders novel questions to do with fluid dispossessions at a time of rising oceans.

On the sand of a small half-moon bay, a once-bright fishing boat is tied to a sea almond tree. When the high tide comes, it pulls the boat, which pulls the tree seawards. When the tide recedes, the tree anchors the boat to dry land. During the highest tides of the year, saltwater bubbles up through the sandy soil, ‘phut, phut, phut’. Water storage urns beneath the two old shore-front bungalows float off. Though over half a century old, these houses only appeared on property records a decade ago, because they stand on land that the sea brought. This socio-environmental ethnography recounts how this seaside land came to be, and how it became private property under the law. In doing so, it gives the history of a place from the perspectives of people who are connected to it in different ways, from the 1950s until the present day.

This story begins before the shoreline in this small stretch of coast changed and expanded enough so that landowners were able to obtain title deeds from the government for their naturally accreted land. It begins when the environment, topography and national infrastructure were significantly different. It tells of how a man built a small porous breakwater to save a tree, how a strip of shore expanded enough so that my great-grandfather was able to build two beach bungalows on it, and thirty years later, my family’s fight for legal recognition of ownership in courts of law, long after all neighbouring properties were titled and deeded. Fleshing out a pursuit that began years ago with participant observation, as daughter of the current owner of this ‘place’, I am pinned to a near immutable positionality by those I converse with. To begin, I reach out to the nearest, and am ensconced in proximity to my octogenarian mother (Khun Mae), going through notes she has taken over the years and sifting through decades of memories, supplemented by archival research, photographs, interviews, corroborations, and cross-questionings. There is no claim to definitive representation here – this is a situated, partial and intersubjective recounting (Haraway Citation1988; Rose Citation1997; Knapp Citation2014). I am learning as I go.Footnote1 In addition to the voices of those I spoke with in Thai (here translated into English), what follows is also told through my mother’s voice, sometimes in English taken down verbatim, or through simultaneous translation by me when in Thai, or else written by her in English. This latter appears in italics. Names of people and places have been changed, while keeping to the spirit of things. I use the term microhistory in a simple sense, to denote that what is recounted is confined to a specific site over a discrete time period (see Ghobrial Citation2019). It is intimate in that it weaves the personal, relational and affective with the archival and what is in the public record. It is contextualised with reference to Thailand’s mid- and late twentieth century land-titling politics ().

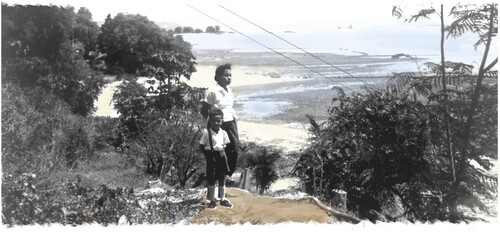

Figure 1. Family and visitors in front of Pa Jan and Lung Wang’s house at Baan Bang Krasae in the late 1970s. My mother, grandmother, grandfather and Lung Wang are standing (left-to-right). Pa Jan is sitting in the centre.

This paper provides a first-hand account of ‘a crucial condition for the existence of capitalist social relations that has received little attention in the literature: the juridical relations that underpin private property’ (Hall Citation2012: 1202). It is about the ‘slippery’ nature of property law, bureaucracy and local politics when it comes to the fluid properties of water (Mehta et al. Citation2012: 194), its ‘inherently political’ nature (Bakker Citation2012; Barnes & Alatout Citation2012), and material agency in changing boundaries of land and sea. As someone familiar with political ecology, some theoretical labelling that came my mind as I began to research Baan Bang Krasae’s property history parallel to thinking about fluid dispossession (Dewan & Nustad CitationThis Issue), was to ask whether my family’s ownership of this small piece of seaside land was some form of primitive accumulation (Marx Citation1995 [1867]), or accumulation by dispossession (Harvey Citation2004)? Thus this paper at the same time demonstrates how ‘assumptions about who carries out primitive accumulation, and who opposes it, are problematic in a rural Southeast Asian context’, and that ‘[u]sing primitive accumulation to understand concrete historical situations is … trickier than is generally recognized’ (Hall Citation2012: 1189). As will be seen, these labels do not encompass what careful attention to place-and people-based history on the small-scale illuminates, in addition to being generally inadequate for describing Thailand’s land politics (Hall Citation2012).

According to Tomas Larsson, modern Thai property law came into being in a context of national securitisation where facilitating land titling and encouraging property ownership by smallholders was a government strategy to counter Thailand’s perceived (and projected) communist threat that began in the first decades of the twentieth century.Footnote2 Within this context, he observes that the anti-communist law of 1933 (actually directed at prominent left-leaning political figures and the state itself rather than an external threat), ‘effectively shut down any discussion that questioned the sanctity of private property rights, irrespective of the ideological basis for such questioning, whether nationalist, socialist or communist’ (2013: 87). While property regimes ‘cannot easily be captured in one-dimensional political, economic or legal models’ (Benda-Beckmann et al. Citation2006: 2), the unquestioning assumption of the ‘sanctity’ of private property rights in Thailand, is an underlying premise of the events and processes narrated in this paper. In the 1950s there was a push by the Thai government to issue land title deeds after the Land Code (1954) was enacted. It was believed that stronger property rights in land would ‘strengthen the agrarian “backbone” of Thai society and boost resistance to the lure of communist ideas’ (Larsson Citation2012: 108).Footnote3 It was during this period that my great-grandparents bought a piece of land on the eastern seaboard.

The House of Currents (Baan Bang Krasae)

Khun Mae recalls:

In the early 1950s my grandparents bought a piece of land on high ground right next to the water to the south of the village of Bang Krasae (Place of Currents). They bought it through Lung Wang (Uncle Hope), who had left his work with the family in Bangkok and moved to Bang Krasae to be a fisherman, but sometimes he would come visit and bring some things, products from the sea like dried fish, salted fish. He learned the fisherman’s skills very well! I saw an old photograph of him holding a sizeable swordfish in front of his small fishing boat. Pa Jan (Aunt Gold Apple) in later days would talk about the time when there was plenty of catch from the sea and she could accumulate gold necklaces, bracelets and rings.

From Lung Wang we learned that the owner of the land wanted to sell it, so my grandparents bought it. The original owner of the land was a local man, and my grandparents bought the other part, but put the land in my grandfather’s name, because it came down to my mother from him. Who made money in the family? My grandmother of course. Your great-grandfather was a teacher. But he was head of the family. If it involved going to the Land Department and things like that, it would be he who did it.

My first remembrance of going down to the shore was through a tunnel that had been cleared in the tangled thicket. It went down the slope and emerged on the dirt and farther out, rocky mud flats. The rocks seemed to be arranged in random curves. We were told that this was the villagers’ shellfish collection area when the tide was out. There was little sand in sight. I was there once when the water came all the way up. It was fun to wade through the water. We always called it the Bang Krasae place, ‘thi Bang Krasae’, or the Bang Krasae house, ‘Baan Bang Krasae’ (). It was accessible by an ox-cart track which was a deep rut in the surrounding orchard land. Khun Ta (Grandfather) kept filling in the track with earth, until the piece of land could be reached by car. I don’t remember how long it took to get there from Bangkok, whether we still needed to take a raft over the Bang Kraphong river in those days.

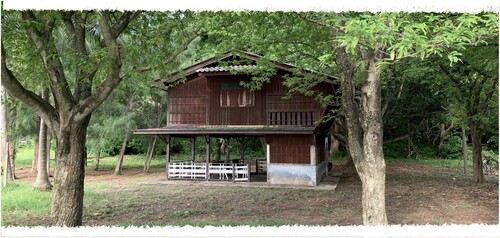

My grandparents asked Lung Wang and Pa Jan to come and live on the land to take care of it. He built them a house on top of the rise near the edge of the slope where two huge tamarind trees stood. Nobody knew how long they had been there. The slope was cleared of brush and planted; stairs were cut on the north side of the slope close to Pa Jan and Lung Wang’s house. Lung Wang built the ‘kuen’ [here, a low crude barrier made of rocks cemented together] because sometimes the water would come all the way to the foot of the stairs. Fearing that land erosion might one day topple the big tamarinds he came up with a bright idea of building perpendicular and horizontal ‘kuen’ to slow down the erosion. I remember he bought rocks by the truckload and they dumped it down the slope. And then he carried the rocks out to make small ‘kuen’. The result was spectacular. In only a few years, nature brought in more and more sand, enough for grandfather to build another two small beach-side bungalows.

In these early days of our family’s coming into this area, the nearby town of Chai Talay was still a land-frontier, with poor road connection to Bangkok, and even poorer road connections going farther eastwards and southwards. The seas and shores were livelier then. Even in the 1960s, dugong (locally known as moo talay, ‘sea pigs’) were reportedly still living off this part of Thailand’s coast, and there was still sea-grass in the shallows and mangroves along the shores. In these parts, the shellfish were plentiful and there for the collecting – bean clams, button-top shells, Venus shells and more. The offshore waters were also well-known to have lots of sharks.

When Lung Wang started his fishing career he and Pa Jan went to a province which in those days could be reached only by water and the early, primitive, narrow and not well-maintained version of Sukhumvit road. They bought a small wooden fishing boat and the two of them sailed the boat back through the shark-infested waters of Chong Samosorn, now part of the Royal Thai naval base. Pa Jan told us about seeing triangular fins of sharks cutting the water, so scary in her small boat. The boat served them well. Pa Jan said sometimes she went out on the boat with Lung Wang. One time she waited on shore and Lung Wang came back with a boat full of sting rays. One time she went out with him at night with a big lamp to lure the fish. But it attracted a huge sea snake instead. They turned off the light, and fled.

It is 70 years since those days, and we are sitting in the shade beneath one of the beach bungalows. They are one-storey high, raised on stilts, with most of the ground-level left open for sheltering from the sun. We are chatting with a few old-timers. Nai Ek is in his 80s and grew up along the Bang Krasae canal in the nearby village; it was his father who sold the Baan Bang Krasae land to my great-grandfather. Nai Chang is the paterfamilias of the extended family who do their inshore fishing from Baan Bang Krasae. They animatedly recount what it was like here when they were children. Nai Ek tells us how after school he would row up the coast to where the Fisheries station now is, to collect water in empty sugar palm tins, as there was no municipal water at his house in those days. He fetched rice-cooking water from a nearby pond (now inaccessible and part of someone’s private land), and drinking water from over by Hin Daeng, ‘Red Rocks’, because ‘there the water was sweet, whitish and clear. We would put galvanised steel sheets into the ground where it came out, and use cloth to filter it’.

Figure 2. My grandmother and youngest uncle looking over the coastline of Baan Bang Krasae in the late 1950s.

In those days, the coastline didn’t look as it does now at all, both men say. The bay curved in and away from the Baan Bang Krasae land, which was slightly higher ground, and there were waterfalls along the shore. The rock semi-circles made by the shellfish farmers that my mother saw as a teenager were not yet here, and the beach was smooth. It was, they both emphasise, far prettier then. ‘When I was a child … this was raised ground, where there was lots of wild grass. Later in the cool season when the kite winds came, the round seed heads of this wild grass would mature and fall from the stems when the wind blew, and they would tumble along, “grok grok grok”, into the water. We liked to come here and sit and watch that, because this was a beautiful place’, Nai Ek says. ‘In the old days, nobody wanted this area’, he continues. Nai Chang adds, ‘In former times, this was all overgrown with naam sema (a kind of cactus) … who would want it? There was no living to be made here, you couldn’t plant things or grow tapioca’.

Land from the State, Land from the Sea

The land title deed (chanote), is dated Buddhist Era 2495 (CE 1952) with my great-grandfather’s name written on it. It is very large, brown, waxy and crinkled, folded in half to fit into the same folders and files as the other documents. The first of the (ultimately) two title deeds that define Baan Bang Krasae the place as ‘property’, is a different creature altogether from other title deeds I have seen. It has the parchment-like appearance and texture of (my imagined) treasure maps. We don’t know whether there was an earlier title deed previous to this, but his name is the first on this one. It is also the case with the second title deed that my mother’s name is the first on it. But with the second one, we know it is the only title deed that Baan Bang Krasae’s beachfront land has had, because it was the first time that part of the land got recognition of existence as private property, although my generation grew up ignorant that the land wasn’t titled.

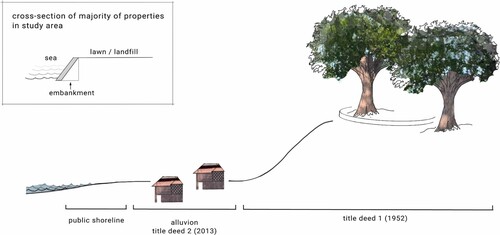

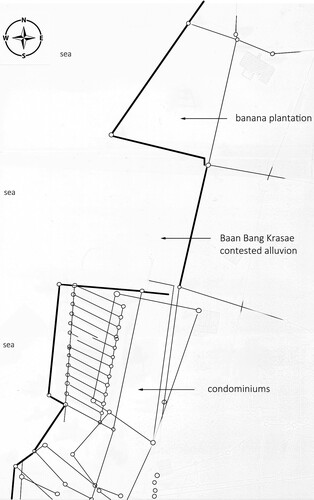

Land from the state, and land from the sea: in the case of Baan Bang Krasae, the former (the title deed issued in 1952) was legally, bureaucratically, administratively visible; the other (where the two bungalows have stood since the late 1950s), invisible. In the eyes of the people who dwell here, Baan Bang Krasae is one place – not two property title deeds.Footnote4 The rest of this microhistory recounts how the second land title deed came to be issued over forty years after the two seaside houses had been built on it. Although it was privately tended land, it was invisible and unrecognised in Land Department records (see ), and became subject to different claims and interpretations in courts of law.

Figure 3. ‘ … our place was like a “fun lor” (gap tooth) there in the row of coastal title deeds issued by the Land Department.’ Illustration traced from cadastral map by Eric Drury.

The term for land accretion, thi ngok, literally means ‘sprouted land’ in Thai. In English, the legal term for this is ‘alluvion’. While it came from the sea and grew from the sea, how the alluvion at Baan Bang Krasae came to be and how it grew, became key issues in this case of coastal property contestation. My grandmother received Baan Bang Krasae from her parents, and until she died, it was considered a place belonging to the extended family as a whole, though by the time I was grown, few of the family regularly stayed or visited there outside of family trips, excepting my mother, who loved Pa Jan and would go to stay with her when she could.

Khun Ta [grandfather] died in 2508 (1965). Then, they had already built the two houses below, which meant that it was already a ‘thi ngok’. The land extended to the north and south of our house – to the extent where the neighbour to the south could later construct a condominium on it. And the neighbour to the north where the ‘thi ngok’ also extended, that land kept changing hands, until at some point they built a big embankment and filled in the land (with imported soil). On both sides of us, they were able to get their land title deeds for the accreted land (‘chanote thi ngok’), but we didn’t manage to get it until many decades later, so our place was like a ‘fun lor’ (gap tooth) there in the row of coastal title deeds issued by the Land Department.

Peter Vandergeest and Nancy Peluso have written about the internal territorialisation of the Thai state based on the ‘abstract space’ of scientific mapping and surveying. They rightly point out that in contrast, peoples’ ‘[e]xperienced territory or space is not abstract and homogenous, but located, relative, and varied’, and territorial land-use planning ‘ignores and contradicts peoples’ lived social relationships and the histories of their interactions with the land’ (Citation1995: 389). The case of Baan Bang Krasae provides a non-dialectical counterpoint, where the invisibility of the place as property and the dispossession of ownership that entailed, pushed the claim for abstract representation in cadastral maps, so as to validate lived social relationships and histories with the land. In this particular case, spatial invisibility in the public administration system was motivation for pursuing the ‘right’ to visibility via land titling.

In 2533 (1990) my grandmother asked the Land Department to issue a title deed for the accreted land on which the two beach houses had stood for some thirty years surrounded by trees, tended and cared for by Lung Wang and Pa Jan. She made the petition on the basis that neighbouring property-owners (no longer the original buyers) had all been granted title deeds for their similarly accreted lands, which were contiguous with, and indeed had grown from the land where Baan Bang Krasae’s two seaside houses stood. The neighbour to the north had obtained his title deed in 1990. According to the locals, he owned entertainment venues and massage parlour(s) in a nearby city, and had political influence (mee itipon). As for the condominium on the land to the south, that land had belonged to Nai Chang’s foster mother, a villager. According to him, together with her siblings, she used her ‘right’ (siti) to obtain a title deed to the accretion and sold it on to a property developer, who built the condominium and sold the units as holiday apartments.

While the Land Department had issued deeds to Baan Bang Krasae’s neighbours, at the time of my grandmother’s petition in 1990, the Kamnan (Sub-district Chief) asked her for 300,000 Baht ($24,000 in 2021Footnote5), which she was unable to pay. However, ‘That wasn’t something we could tell the court or anyone’ my mother remarked, when we were trying to make sense of the internally contradictory statements from the Land Department and public prosecution on why the land could not be titled. They could give any reasons they wanted and it didn’t matter if they made sense or not, she reflected, because they (the local government and bureaucrats concerned) were not going to issue the deed (without the bribe). Local government and bureaucrats had captured state interests, and were trading in it, a practice of ‘everyday corruption’ (Blundo et al. Citation2006). Doing this within the modernist framework of legitibilitisation via cadastral surveys (Scott Citation1999), they used the bureaucratic tactic of indefinite waiting (Auyero Citation2012) and would not ‘see like a state’, until citizens gave them personal incentive to do so.Footnote6

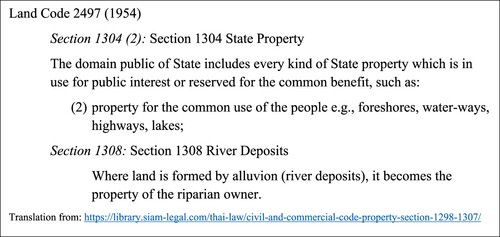

Seven years after my grandmother submitted her request, the Land Department’s ‘Committee for considering the issuance of title deeds for seaside alluvion’ issued a note sheet regarding the land surveyed, observing that: ‘the land abuts the seashore’, that the already existing title deed (purchased in my great-grandfather's name) stipulates that it abuts shoreline, not the sea (‘“chai talai” mi chai thid “talay”’) and therefore the question of whether or not it is possible to issue a land title deed as private property in accordance with Section 1308 of the Civil and Commercial Law Code should be forwarded to the provincial public prosecution as a question of law; upon consideration which the provincial prosecution was of the opinion that the land for which my grandmother requested the issuance of a title deed, was public commons land as per the Civil and Commercial Law Code Section 1304 (2).Footnote7 According to the document, the matter would remain under consideration, and there it sat for the next eleven years, until my grandmother withdrew her request and passed ownership of the land down to my mother in 2544 (2001). Fourteen years after our neighbours were granted deeds on land contiguous with ours, Khun Mae again applied for a title deed in 2004. The Land Department again refused, citing their rejection of my grandmother’s application – though documents from the provincial office of the Land Department itself, stated that the matter was still ‘under consideration’ ().

Suing the State

And so with the advice and assistance of an astute and ambitious local lawyer, my mother gave up waiting, and sued the Land Department to issue a title deed to the land on which the two bungalows stood. The case was first submitted to the Administrative Court, the newly established branch of the judiciary responsible for grievances against state agencies. The Administrative Court said that as this was a matter to do with land rights, it was therefore a matter for the Courts of Justice. The lawsuit named three defendants: The Land Department, the Chief of Charoensi Provincial Land Department, and the Chief of the Bang Krasae branch of the Provincial Land Department.

The Court of First Instance (CFI, in this case, the local civil court), which is where testimonies are taken, came to the decision that the defendants could not be sued for refusing to issue a land title deed because they could not do so by law, that the land was not alluvion, and that it was public domain land that was in common use. They therefore threw out the suit. The case was then submitted to the Court of Appeals, who upheld the ruling of the Court of First Instance, with additional deliberation on the status of the piece of land in question, saying that even if it is alluvion, the title deed cannot be issued, with the notable directive that the title deeds issued to the neighbours for their contiguous pieces of land should not be used as precedent.

Shoreline Semantics of Thi Ngok, ‘Sprouted Land’ (Alluvion)

A main concern in this case, was whether the land in question was to be accepted as thi ngok or not. Thi ngok, literally ‘sprouted land’ in Thai, is accreted land, or alluvion in legal English: ‘The formation of new land by the usually slow and imperceptible action of flowing water’ (OED Citation2021). What could be interpreted as alluvion however, seemed fluidly contingent on different factors and was differently interpreted by the various parties involved.Footnote8 The crux of the matter as regards what is alluvion and what is seashore entangled considerations of whether it was natural or not, and whether it should be considered private (and able to be deeded) or state property. The claims made by the various agencies involved are summarised in the following paragraph.

The Charoensi Province Land Department claimed that while the existing title deed is described as abutting the shore and not the sea (tid chai talay mi chai tid talay), the distinction between whether the existing title deed abuts the shore or the sea, is an important one as regards to whether title deed can be issued in accordance to Section 1308 of the Land Code, and the public prosecutor would need to be consulted on the matter of law. The Court of First Instance was of the opinion that the land was not natural alluvion, and was public domain land belonging to the state, and that it was used as public commons. The Court of Appeals reasoned that because the plaintiff testified that their land ‘abuts the seashore’, that land therefore is seashore (and not alluvion),Footnote9 and thus in the public domain of the state according to the Civil and Commercial Law Code section 1304 (2), but even if there is naturally occurring change whereby the sea becomes more shallow until the high tide does not reach the land (i.e. even if it is alluvion), it is public domain.

In trying to tease sense out of the various knowledge claims and definitions around shore, edge, etc., unravelling one contradiction to be met with another of improbable logic and incommensurability (Hull Citation2012a; Citation2012b), the question of ‘how does it matter?’ comes up. Here, the semantics of shoreline and alluvion seemed to matter most in a performative and discursive way – deployed as an instance of state and bureaucratic power/knowledge (Foucault Citation1988) in the contestation of coastal property rights. It was not the words or their definitions that had importance in themselves, but it was through these means that bureaucratic power was asserted to obfuscate and hold to a predetermined decision (see Herzfeld Citation2005; Citation2014).

They had already made a decision, these people, they use language to confuse us as to what is the sea, what is the seaside. They already decided that they were not going to issue the title deed from the beginning. Even if the official moved from the Nai Ampur (Chief District Officer) to Palat Changwat (Deputy Province Chief) [as they would be, in the normal course of civil service promotions], whatever he said and wanted, he will stick with that.

Nine years later, in 2556 (2013) the case went to the Supreme Court, which overturned the rulings of both lower courts, and ordered the Land Department to issue a title deed. The Supreme Court ruled that the accreted land was natural alluvion, and thus according to the Civil and Commercial Law Code Section 1308, ‘the property of the riparian owner’ (see ). A title deed could be issued for the land in question, contiguous with Baan Bang Krasae’s already existing title deed. Justifications given for the Supreme Court decision were that: the plaintiff’s case and supporting testimonies were more credible; it showed place-based familiarity with the site, and that while the Land Department had the technical expertise and opportunity to conduct a site investigation, it did not do so. It was therefore the duty of the Land Department to issue a title deed to the plaintiff.

In the trial, many people came to give evidence. One person that the Supreme Court believed in was a man who had formerly been Sub-District Chief for sixteen years, who was called to give impartial testimony, who we had no personal relationship with. His words had weight and were considered reliable by the Supreme Court, more so than the state officials such as the Land Department officials, the Chief District Officer and Deputy Province Chief, who the Supreme Court said spoke with assumptions and conjecture (‘kard gaan’) – they did not investigate whether the land was filled-in [with imported soil etc.], or whether the sea had brought it.

Shifting Sands and Fluid Socio-Natures

Poring over and discussing the court documents and definitions revealed that interpretation and argumentation on the points of law were flexible in a court of law (and in this case, likely irrelevant to the final outcome, where motivating factors for the decisions made at various levels and by various parties seemed to pre-exist the reasons mustered in support of them). A clear line of logic or argumentation, if one could be traced, did not ensure the dovetailing of referent and definitions, nor of facts and statements. There also seemed to be no clear relationship between alluvion and public domain land, and the two sections of the law code repeatedly referenced by the opposing parties () allowed for conflicting interpretations.

The distinction I was initially interested in while studying the documents, was to do with the perception of what is ‘natural’, what is ‘human manufactured’, and what is agency, in this particular context. The court documents were unclear as to whether the land on which the two bungalows had stood for half a century, was to be considered natural or human-made, according to the law. While it was apparent that the human/nature distinction was intrinsic to the legal definition of alluvion (it couldn’t be by human manufacture), the Thai definition of alluvion, ‘where the water becomes shallower until it does not cover the land at high tide’ lends the water an agency more explicit than in English, so that what is considered land, is defined by the water’s movement. This non-fixity of position was likewise reflected in my cross-examinations of key informants.

Did the alluvion occur naturally or not?

Well the ‘kuen’ was built and the water current naturally carried in more sand to become accreted land – it happened on its own, that is, no one went and did anything further (filled it in with landfill as done in neighbouring properties).

Did the alluvion occur naturally or not?

Well no, because Lung Wang built a kuen [crude barrier] to dissuade the highest tides from washing away the large tamarind trees.

Well yes, because it was the sea that brought the sand in, through the rock barriers (kuen), until it became alluvion.

Then Nai Ek’s explanation further complicated the causality:

Do you know how the sand got to where we are and to the surrounding properties? Because during this cool season (end of year), the sand comes this way, right, and it piles up here. During Okasai wind season you will get a lot of sand, it will come this way, it sticks to the land where we are and it grows out towards the sea because here it’s a bank that goes out, and there are old trees, ancient trees, that the owner of the property took care of.

Recognising the co-agency of the currents, sand and the trees in creating the alluvion enlarges the frame of causality, and further blurs the distinction between human and non-human agencies. It leaves behind rigid Cartesian dichotomies in favour of socio-natures (Castree & Braun Citation2001) or socio-natural assemblage and hybridisation (Bakker Citation2012, also referencing Swyngedouw (Citation1999)) as explanatory framings for the processes by which the alluvion came to be. ‘[P]roperty law entails the assignation of objects, people and relationships to supposedly discrete and stable categories. One central distinction, for example, is that made between private and public property’ (Blomley Citation2008: 1826; Benda-Beckman et al. Citation2006). The shifting shoreline destabilises the distinction between private and public; like the sand that the sea brought in, the Baan Bang Krasae case perforates the legal barrier between nature and human. It is an example of how expanded notions of agency that the idea of the Anthropocene is diffusing into the social sciences might affect law and sub-disciplines that have to do with the interpretation of law (such as legal anthropology and geographies of law).

Thinking from a Shoreline Place

If the notion of a pure nature-an-Sich has died in the Anthropocene and been replaced by natural worlds that are inextricable from the worlds of humans, then humans themselves can no longer be what classical anthropology and human sciences thought they were. (Haraway et al. Citation2016: 535)

Thinking with Baan Bang Krasae poses questions for the idea of ‘fluid dispossessions’ (Dewan & Nustad CitationThis Issue) in capitalist societies from a shoreline place. Thinking from a shoreline place brings to surface the question of how well do land-based assumptions work for coastal and marine matters, particularly in places with shifting boundaries in times of fluid socio-natures? General ideas of ‘land grabbing’ are already confounded to a degree in Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries with a large agrarian smallholder farming base (Vandergeest & Peluso Citation1995; Hall Citation2012). The story of Baan Bang Krasae land titling foregrounds the fluidity of possession and dispossession of coastal land, but what about the surrounding waters? ().

From a shoreline place, we are uniquely placed to ask, ‘to what extent property laws directed at those with land-based livelihoods overlook those many communities and individuals whose traditional livelihoods are with the coast and the sea?’ (see also Subramanian Citation2009; Bhattacharyya Citation2018). While some of these people may not be directly dispossessed by land grabbing or ‘green-grabbing’ (Fairhead et al. Citation2012), they and others are vulnerable to ocean or ‘blue-grabbing’ in its various manifestations, including industrial water pollution and large-scale commercial fishing operations (McCormack Citation2017; Barbesgaard Citation2018).

The small fishing community at Baan Bang Krasae are being backed into a corner by shoreline property enclosures which cut off easy access to the sea. They also seek their livelihoods downstream of ‘water grabbing’ processes where ‘local communities suffer from pollution by upstream powerful actors’ (Mehta et al. Citation2012: 201) such as corporate externalisation of pollution from upstream factories, while at the same time being dependent on a mobile resource (e.g., fish). From their perspective, dispossessions are fluid and multiple: they are being deprived of their livelihoods through water pollution which kills the shellfish and chases away the catch; their access to shoreline for their fishing and gleaning operations is being cut-off, and in the sea there is more competition and less catch.

Multiple and Diverse Dispossessions

Since those days in the early 1950s, this strip of coast has been all bought up by private individuals, save for parts deemed state land, and small public access strips leading down to the shore. Today, there are no more curving bays here, save the small half-moon bay where Baan Bang Krasae is. Lung Wang is long gone, as is Pa Jan, who died in 2014. The sea around here is dying: full of plastic and other pollution, often poisoned (Suvapepun Citation1991; Cheevaporn & Menasveta Citation2003; Marks et al. Citation2020). There are no more sharks of note, in what was once a notoriously shark-infested area. There’s no more forest for logging, but housing developments and factories replacing smallholder tapioca and sugarcane plantations and orchards inland, amid the growing footprint of automobile plants, shipping seaports, industrial estates and massive godowns. An eight-lane motorway comes from Bangkok and shoots on to the Cambodian border. The land along this coast is a strip of Thai and foreign investment, now marketed towards a more grandiose future as Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor project, readying to become an accretion of China’s Belt and Road initiative.

We are sitting on the high ground by the giant tamarinds one evening. Nai Chang and his younger brother join us. I ask them how the fishing has been.

It's no longer cool. Before, with the cool weather, you can fish for squid by the shore, they come in. Now there’s also no more seaweed to feed the fish nurseries, there are no crabs, no fish. Things have become more developed. These days, with economic development, commercial boats come in, we don’t know what they wash into the sea. There is no real inspection. It is the same with the rubbish. What comes in with the water when I clean the beach, it’s all from humans … The polluted water comes in the rainy season. It comes with the flood waters. The factories probably also sneak to release polluted water along with the fresh water that comes down from the north. It’s clear, but it’s as if it is poisonous. The fish and the crabs won’t settle on the bottom when it comes.

In other places, public access ways to the beach have been blocked off and enclosed – even where there were once bays, these areas have been landfilled, until the shoreline is near straight, with high embankments separating land from water, some with turfed lawns growing to the salt-sea edge. ‘Who is able to do this?’, I ask. ‘They are powerful people, no one can touch them’, the fishermen tell me. The nearest public use lands have been turned into seaside promenades and concreted over for an imagined leisurely and paying public, not for the inshore fishers. Where once there were toponyms that spoke of landscape features, Hin Khao (‘White Rock’), Hin Daeng (‘Red Rock’), now there are branded places – ‘x’ shopping mall, ‘y’ shopping mall. The dispossession is not only of rights of use and access under the law, but dispossession of the history of this patch of coastline, expressed in the old toponyms and the lived memories between people and place (Basso Citation1996), and of possible futures.

Conclusion

Through a microhistory of coastal property contestation, this paper has extended the critique of the dichotomy and homogeneity of who is dispossessed by whom (e.g. Levien Citation2011) to include the relatively elite, other parts of the state itself, and the instability of ‘how we determine what counts as primitive accumulation’, whether it be the characteristics, the consequences or the intentions behind it (Hall Citation2012: 1195), to which I add the temporal bounds of the process under analysis. This points to the importance of not only scale and agency in political ecology, which have respectively been much and increasingly theorised, but also to temporality, related to the understanding of chains of causation integral to political ecology (Watts Citation2015). Knut Nustad (Citation2020) has called for more attention to be paid to time in political ecology analyses; to this can be added a call for attention to the temporalities inherent in the formulation and usage of theoretical labels. Over the seventy years and four generations of Baan Bang Krasae’s existence, there has been no surplus value generated here that could or would be used to reproduce capital on an expanding scale – except for the rising price of land itself. The land ownership pattern along this strip of coast cannot be conformed to Marx’s primitive accumulation via violence and dispossession; nor is it David Harvey’s accumulation by dispossession, requiring global flows of capital and monopolisation of resources – at least not yet, not within the current timeframe or scale of analysis.

These labels would seem to exclude rather than encompass what careful attention to place-and people-based history on the small scale can illuminate.Footnote11 And perhaps what this kind of attention illuminates is the less dramatic beginnings of dispossession in more humble market economies that allows for agency. For example, while the fisher family still retain some of their own land next door, they appear to have closed off the public access way to the beach from there, and are themselves not interested in allowing common access or using the shoreline as commons: even out in the water, it is all territorialised, and money changes hands for right of use in areas of shellfish farming – and appears to have done so for a very long time (see Li Citation2014b). Even the long-ago seen semicircles of oyster farming rocks had owners, and were considered private property. Nai Ek’s father, who sold my great-grandparents the original plot of land, was a villager and fisherman; for him it had no agricultural value, and so he found a buyer through Lung Wang. As Derek Hall notes, ‘If opposition to primitive accumulation by states and firms receives scattered coverage in the literature, the possibility that direct producers might be in favor of it – that they might want, for instance, to enclose land, or to “self dispossess” (Hetherington Citation2009: 227) by selling it-has barely been considered’ (Citation2012: 1198, see also Li Citation2014a).

Today, Baan Bang Krasae is surrounded by ever-increasing vegetation (). A couple of years ago a location scout wandered in to ask whether they might shoot a period film there, perhaps a ghost story. It would be a good place for this, if one were not already aware of its ‘cosmopolitical ecology’ (Kuyakanon et al. Citation2022): the spirits already living here, who might not like the disturbance of a film production. Local rumour of powerful spiritsFootnote12 has kept the two beach bungalows undisturbed by squatters or those looking for a place for recreational drug use – no one will spend the night there, because inexplicably loud and frightening noises warn intruders that the spirits do not like intrusion. While this has helped towards preserving the houses, it has the reverse effect on the care of the very large trees here – no one is willing to prune broken or rotting branches from the giant tamarinds at the top of the rise, for fear of supernatural reprisal. The irony of Baan Bang Krasae is that if the private property goes, it is likely that the spirits that dwell here, the flora and fauna that are still home in this relict bit of coast, and the fisher people who rely on this stretch of shore, may all go.

In this paper I have detailed how alluvion came into existence through a socio-natural process, and how it became legal property through a lawsuit. By relating an intimate history made possible through lived experiences, affection and enduring relations, I attempted to capture the meanings of processes in terms of contemporaneous valuations rather than later interpretations. I have recounted the history of my family’s court case(s) against potential land dispossession through state practices of illegibility, entanglements of legalese, anthropogenic agency and the inshore fishers’ exclusions at the margins of a capitalist system. I have illustrated how Thai legal semantics around ‘shoreline’ prefigures socio-natures ideas and analyses, as regards the materiality of water and its agentive role, be it holding sand in suspension to build alluvion and change boundaries, or bearing the pollution that comes with the currents. I have engaged with an extended political ecological question of who (or what) is dispossessed, when, where, why, how and by whom (or what) and problematised it at the granular scale. In doing so from a shoreline place, this paper makes a contribution to anthropological theorising on changing interpretations of agency in the Anthropocene, and raises new questions for understanding property contestations in an era of rising seas and accelerated climate change.

Acknowledgements

In addition to those whose voices appear here, I am most grateful to my mother and to my father for the productive and enjoyable hours spent discussing the events this paper describes. My sincerest appreciation to Camelia Dewan and Knut Nustad for organising the Contested Waters workshop at the POLLEN Conference 2020 and making this paper happen, and to the ultra-core Southeast Asia Reading Group. I am deeply grateful to Eszter K. Kovacs, Rebecca Knapp, and especially Sathaporn Bromma for their counsel, and two anonymous reviewers for their inspiring generosity of engagement.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This microhistory of land titling is one grain of an envisioned larger project that will weave stories of entities that dwell in place, land and sea, into wider histories and political ecologies.

2 In brief, Larsson argues that on the one hand, the government employed institutional underdevelopment to avoid the penetration of colonial capital into the Thai hinterland, and once unequal treaties with the colonial powers had been abrogated, it countered the subsequent communist threat by pushing land titling that targeted Thailand’s smallholder farmers, the ‘backbone’ of the nation (2013).

3 Larsson’s argument relies primarily on extensive archival research; other explanations (not necessarily contradictory) that are less well-documented/researched may exist (see Barney Citation2016). These meso-level factors include class interest, lower child mortality, increasingly smaller land holdings, and debt entrapment as farmers borrowed beyond their ability to repay in order to participate in the Green Revolution.

4 The material turn in anthropology to documents as mediators and citizen-state subjectivities is important (see, e.g. Das Citation2004; Gupta & Sharma Citation2006) but what I convey here is affect.

5 This is based on the current consumer price index of 262 versus the 128 in 1990.

6 Gupta (Citation1995; Citation2012) and Heyman’s (Citation2004; Citation2012) work on the power of the bureaucracy, the deployment of ‘red tape’ and corruption is relevant here.

7 Duncan McCargo’s work deals extensively and intimately with the complexity and opacity of the Thai legal system. See, e.g. McCargo (Citation2014, Citation2015a, Citation2015b).

8 An interesting watery point, is that the Thai legal language for alluvion or ‘thi ngok’, seems predisposed towards riverine communities and property, rather than marine. Because both sections of the Land Code under contention use the word ‘taling’ (bank – of river or canal) it had to be argued by the plaintiff that river bank has the same meaning as seashore because in Thai common understanding and usage ‘taling’ is associated with rivers and inland bodies of water, not the sea (the English ‘alluvion’ doesn’t have this problem). What might be the implications of using riverine language for coastal processes? As regards the case under discussion, Michael Herzfeld’s observations on the state’s use of legalese to dispossess is pertinent (e.g. Citation2005, see also Povinelli Citation2002), but in this case, it proved to be a double-edged sword.

9 An example of improbable logic: if land abutting seashore is seashore, then most/all of Thailand could be seashore.

10 The case of shifting sands and coastal property also raises the question of national economic security: for example, an enormous amount of money has been poured into the sea as the government has tried to prevent erosion of touristic beaches.

11 These framings with the sweeping weight of English and other histories behind them, while they may ‘account for some processes, structures, and differences, they do little to elucidate the conditions that allow such structures to take form and organize the world’ (Sage Citation2006: 117). Applied at the granular level, in this particular case, they do not capture the essence of processes, the use to which the land was put, or reflect that the attachment to place has been almost entirely sentimental, economically supported by expenditure rather than sustained with income.

12 See Julia Cassiniti (Citation2022) and Andrew Alan Johnson (Citation2020) for their work on cosmological ecological politics in north and northeast Thailand, and Götz & Middleton (Citation2020) on onto-politics of water.

References

- Auyero, Javier. 2012. Patients of the State: The Politics of Waiting in Argentina. Chapel Hill: Duke University Press.

- Bakker, Karen. 2012. Water: Political, Biopolitical, Material. Social Studies of Science, 42(4):616–623.

- Barbesgaard, Mads. 2018. Blue Growth: Savior or Ocean Grabbing? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 45(1):130–149.

- Barnes, Jessica & Samer Alatout. 2012. Water Worlds: Introduction to the Special Issue of Social Studies of Science. Social Studies of Science, 42(4):483–488.

- Barney, Keith. 2016. Land and Loyalty: Security and the Development of Property Rights in Thailand. By Tomas Larsson. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2012. Xii, 208 Pp. ISBN 9780801450815 (Cloth). The Journal of Asian Studies, 75:270–273.

- Basso, Keith H. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Benda-Beckmann, Franz von, Keebet von Benda-Beckmann & Melanie Wiber (eds). 2006. The Properties of Property. In Changing Properties of Property, 1–39. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Bhattacharyya, Debjani. 2018. Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Blomley, Nicholas. 2008. Simplification is Complicated: Property, Nature, and the Rivers of Law. Environment and Planning A, 40:1825–1842.

- Blundo, Giorgio, Jean-Pierre Olivier de-Sardan, N. Bako Arifari & M. Tidjani Alou. 2006. Everyday Corruption and the State: Citizens and Public Officials in Africa. Cape Town: Zed Books.

- Cassiniti, Julia. 2022. Up in smoke: cosmopolitical ecologies and the disappearing spirits of the land in Thailand's agricultural air pollution. In Cosmopolitical Ecologies Across Asia: Places and Practices of Power in Changing Environments, edited by Riamsara Kuyakanon, Hildegard Diemberger and David Sneath, 62–80. London: Routledge.

- Castree, Noel & Bruce Braun. 2001. Socializing Nature: Theory, Practice, and Politics. In Social Nature: Theory, Practice, and Politics, edited by Noel Castree and Bruce Braun, 1–21. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Cheevaporn, Voravit & Piamsak Menasveta. 2003. Water Pollution and Habitat Degradation in the Gulf of Thailand. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 47(1):43–51.

- Das, Veena. 2004. The Signature of the State: The Paradox of Illegibility. In Anthropology in the Margins of the State, edited by Veena Das and Deborah Poole, 225–252. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Dewan, Camelia & Knut Nustad. This Issue. Introduction to Special Issue. Fluid Dispossessions: Contested Waters in Capitalist Natures. Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology.

- Fairhead, James, Melissa Leach & Ian Scoones. 2012. Green Grabbing: A New Appropriation of Nature? The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2):237–261.

- Foucault, Michel. 1988. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. 1st American ed.). New York: Random House.

- Ghobrial, John-Paul A. 2019. Introduction: Seeing the World Like a Microhistorian. Past & Present, 242(Supplement 14):1–22.

- Götz, Johanna M. & Carl Middleton. 2020. Ontological Politics of Hydrosocial Territories in the Salween River Basin, Myanmar/Burma. Political Geography, 78:102115.

- Gupta, Akhil. 1995. Blurred Boundaries: The Discourse of Corruption, the Culture of Politics, and the Imagined State. American Ethnologist, 22(2):375–402.

- Gupta, Akhil. 2012. Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Gupta, Akhil & Aradhana Sharma. 2006. Globalization and Postcolonial States. Current Anthropology, 47(2):277–307.

- Hall, Derek. 2012. Rethinking Primitive Accumulation: Theoretical Tensions and Rural Southeast Asian Complexities’. Antipode, 44(4):1188–1208.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3):575–599.

- Haraway, Donna, Noboru Ishikawa, Scott F. Gilbert, Kenneth Olwig, Anna L. Tsing & Nils Bubandt. 2016. Anthropologists Are Talking – About the Anthropocene. Ethnos, 81(3):535–564.

- Harvey, David. 2004. The ‘New’ Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession. Socialist Register, 40:63–87.

- Herzfeld, Michael. 2005. Political Optics and the Occlusion of Intimate Knowledge. American Anthropologist, 107(3):369–376.

- Herzfeld, Michael. 2014. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. London: Routledge.

- Hetherington, Kregg. 2009. Privatizing the Private in Rural Paraguay: Precarious Lots and the Materiality of Rights. American Ethnologist, 36(2):224–241.

- Heyman, Josiah. 2004. The Anthropology of Power-Wielding Bureaucracies. Human Organization, 63(4):487–500.

- Heyman, Josiah. 2012. ‘Deepening the Anthropology of Bureaucracy’ Edited by A. Gupta, K. Hetherington, and M. S. Hull. Anthropological Quarterly, 85(4):1269–1277.

- Hull, Matthew S. 2012a. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Hull, Matthew S. 2012b. Documents and Bureaucracy. Annual Review of Anthropology, 41:251–267.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2021. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by Valérie Masson-Delmotte , P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou, 4–36. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, Andrew Alan. 2020. Mekong Dreaming: Life and Death Along a Changing River. Chapel Hill: Duke University Press.

- Knapp, Riamsara Kuyakanon. 2014. When Does ‘Fieldwork’ Begin? Negotiating Pre-Field Ethical Challenges: Experiences in ‘the Academy’ and Planning Fieldwork in Bhutan. In Fieldwork in the Global South: Ethical Challenges and Dilemmas, edited by Jenny Lunn, 13–24. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kuyakanon, Riamsara, Hildegard Diemberger & David Sneath (eds). 2022. Cosmopolitical Ecologies Across Asia: Places and Practices of Power in Changing Environments. London: Routledge.

- Larsson, Tomas. 2012. Land and Loyalty: Security and the Development of Property Rights in Thailand. Cornell Studies in Political Economy Series. Cornell University Press.

- Levien, Michael. 2011. Special Economic Zones and Accumulation by Dispossession in India. Journal of Agrarian Change, 11(4):454–483.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2014a. Land’s End: Capitalist Relations on an Indigenous Frontier. Chapel Hill: Duke University Press.

- Li, Tania Murray. 2014b. What Is Land? Assembling a Resource for Global Investment. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 39:589–602.

- Marks, Danny, Michelle Ann Miller & Sujitra Vassanadumrongdee. 2020. The Geopolitical Economy of Thailand’s Marine Plastic Pollution Crisis’. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 61(2):266–282.

- Marx, Karl. 1995 [1867]. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Vol. I Book One: The Process of Production of Capital. First English Edition of 1887. Edited by F. Engels. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- McCargo, Duncan. 2014. Competing Notions of Judicialization in Thailand. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 36(3):417–441.

- McCargo, Duncan. 2015a. Transitional Justice and Its Discontents. Journal of Democracy, 26(2):5–20.

- McCargo, Duncan. 2015b. Readings on Thai Justice: A Review Essay. Asian Studies Review, 39(1):23–37.

- McCormack, Fiona. 2017. Private Oceans: The Enclosure and the Marketisation of the Seas. London: Pluto Press.

- Mehta, Lyla, Gert Jan Veldwisch & Jennifer Franco. 2012. Introduction to the Special Issue: Water Grabbing? Focus on the (Re)Appropriation of Finite Water Resources. Water Alternatives, 5(2):15.

- Nustad, Knut G. 2020. Notes on the Political Ecology of Time: Temporal Aspects of Nature and Conservation in a South African World Heritage Site. Geoforum 111:94–104.

- OED Online. 2021. Oxford University Press. ‘alluvion, n.’. https://www-oed-com (accessed 29 July 2021).

- Povinelli, Elizabeth. 2002. The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism. Chapel Hill: Duke University Press.

- Rose, Gillian. 1997. Situating Knowledges: Positionality, Reflexivities and Other Tactics. Progress in Human Geography 21(3):305–320.

- Sage, Daniel J. 2006. The New Imperialism. The Professional Geographer, 58(1):114–117.

- Scott, James C. 1999. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Subramanian, Ajantha. 2009. Shorelines: Space and Rights in South India. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Suvapepun, Sunee. 1991. Long Term Ecological Changes in the Gulf of Thailand. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 23:213–217.

- Swyngedouw, Erik. 1999. Modernity and Hybridity: Nature, Regeneracionismo, and the Production of the Spanish Waterscape, 1890–1930. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 89(3):443–465.

- Vandergeest, Peter & Nancy Lee Peluso. 1995. Territorialization and State Power in Thailand. Theory and Society, 24(3):385–426.

- Watts, Michael. 2015. Interview with Michael Watts - on Nigeria, Political Ecology, Geographies of Violence, and the History of the Discipline. http://societyandspace.com/material/interviews/interview-with-michael-watts-on-nigeria-political-ecology-geographies-of-violence-and-the-history-of-the-discipline/.