ABSTRACT

This study examines university-driven partnerships that promote entrepreneurship in underserved communities, drawing from the experiences of NCGrowth, an economic development center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We address the following questions: Who are the central stakeholders? How do they interact? What do their challenges and experiences imply for policymaking and practice in nurturing entrepreneurship ecosystems in underserved communities? We employed social-network analyses of NCGrowth’s projects spanning 2013–2019, supplemented by document analysis of archival data and in-depth interviews. The study uncovers highly asymmetric connections among stakeholders, with universities and government agencies emerging as dominant entities, leveraging universities’ specialized knowledge and community relationships. Nevertheless, challenges surface due to overlapping roles as facilitators, the absence of consistent community carriers of development plans, and a dearth of financial institutions. Our findings advocate for an ecosystem-focused approach to economic development in underserved areas, emphasizing the involvement of additional anchor institutions such as hospitals, major corporations, and philanthropists. Furthermore, policies and practices should integrate the objectives of entrepreneurship, economic growth, and social equity to cultivate inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystems.

A highly skilled labor force and entrepreneurship are crucial for the growth of new knowledge economies. In fostering both, higher education institutions (HEIs) function as important actors in promoting innovation and building regional entrepreneurship ecosystems (Bagchi‐Sen and Smith Citation2012; Drucker Citation2016; Audretsch Citation2018). Public policies on research and development (R&D), higher education, and economic development are often combined to promote entrepreneurship and command resources to make large-scale investments in infrastructure and STEM. As such, universities impact not only the economic development trajectories of the places where they are located, but also the physical landscape, social structures, institutional environment, and community capacity building in these places and beyond (Addie et al. Citation2015; Mapes et al. Citation2017; Ehlenz Citation2019).

Embedded within multiscalar networks of learning and governance with broad-based coalitions of state and nonstate actors, universities have acted as key players in combining external resources and influences with local needs (Bagchi‐Sen and Smith Citation2012; Malecki Citation2018). Nonetheless, with a few exceptions (Motoyama and Knowlton Citation2016; Harper-Anderson Citation2019), research has yet to fully explore these partnerships from a network perspective. Furthermore, despite the accumulation of studies in this field, research on the role of universities in entrepreneurship has mainly focused on knowledge transfer via spin-offs, patent applications, the attraction of external funding, and scientific theses and publications (Pugh et al. Citation2016). Although university-based entrepreneurship centers have become important vehicles for a range of programs and services to advance entrepreneurship and economic development, they are seldom focused on underserved communities. O’Brien et al. (Citation2019) explicitly challenge the traditional role of universities in supporting entrepreneurship by focusing mainly on economic growth and new venture creation, and call upon higher education institutions to provide greater civic support for entrepreneurship learning amongst underrepresented communities.

To address these identified gaps, this study examines the structure of university-led partnerships that foster entrepreneurship in underserved communities and the perspectives of local and regional stakeholders. We seek to answer:

Who constitutes the stakeholders within these partnerships?

How do these stakeholders interconnect to one another and the local communities?

What insights do their experiences and hurdles offer regarding promoting entrepreneurship in underserved communities?

This study is based on the practices of NCGrowth, an economic development center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). NCGrowth provides direct technical support to businesses in economically distressed communities in North Carolina and South Carolina. These areas are often characterized by high concentrations of Black, Indigenous, and Latino populations, or a combination of these factors, underscoring the center’s dedication to serving communities that are either economically marginalized, predominantly composed of nonwhite individuals, or both. To address our research questions, we conducted social-network analyses on NCGrowth’s community-based business development projects from 2013 to 2019. Additionally, we conducted in-depth interviews with the center’s local and regional economic development partners, as well as its business clientele.

Results from this study contribute directly to our understanding of the complex relationships between places and universities. This understanding is enriched by drawing from interdisciplinary scholarship on universities’ roles in entrepreneurship ecosystems, racial and ethnic minority entrepreneurship, and university-community engagement (Fairlie and Robb Citation2008; Audretsch Citation2018; Ehlenz Citation2018; Wang Citation2021). This research augments existing knowledge on university-led collaborative entrepreneurship support programs that will aid in tackling the challenges confronted by socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. It also contributes to scholarship on the entrepreneurship ecosystem. Entrepreneurship ecosystems have long been conceptualized as dynamic and interactive networks (Spigel Citation2017; Malecki Citation2018). While empirical analyses from social-network analyses are still rare, and even more lacking for underserved communities, this study creatively combines qualitative and quantitative data from diverse sources. Particularly, instead of relying on stakeholders’ perceptions, we evaluate their interconnectivity through actual participation in the past through a triangulation of data from different sources. In addition, although the data is limited and the process of data collection is time consuming, this study can inform similar research that relies on economic development practices in terms of how to build an alliance between the two.

Universities and Entrepreneurship in Underserved Communities

Entrepreneurship in Underserved Communities

Entrepreneurship has long been theorized as a socio-spatial process (Spigel Citation2017). An “entrepreneurial ecosystem” (EE) perspective argues that conducive culture, enabling policies and leadership, availability of appropriate finance, quality human capital, venture-friendly markets for products, and a range of institutional and infrastructural supports are all important for innovation and entrepreneurship (Isenberg Citation2010; Spigel Citation2017; Malecki Citation2018). While these studies have provided valuable insights, most do not explicitly discuss race and ethnicity.

Ethnic minority-owned businesses (EMOBs) have grown unprecedentedly over recent decades. Notably, minority neighborhoods have become magnets for skilled, accomplished African-American and Latino business proprietors, culminating in substantial strides in job creation, particularly within minority communities (Bates et al. Citation2022). However, substantial barriers have impeded the start-up and growth of EMOBs (Fairlie and Robb Citation2008; Bates et al. Citation2018): lack of human capital, limited access to social and financial capital, and discrimination and marginalization. For instance, in terms of business-management education and experience, racial minorities trail behind their white counterparts. Additionally, African-American and Hispanic entrepreneurs with comparatively lower net worth confront heightened challenges in securing formal financial resources compared to their wealthier peers. This discrepancy is often attributed to their limited social networks and fewer social resources (Casey Citation2012).

These challenges are exacerbated for entrepreneurs of color operating in economically distressed areas, where the absence of infrastructure and entrepreneurial support networks is prevalent. These hindrances result in escalated operational expenses, providing little motivation for profit-focused venture capitalists to invest in such regions (Rubin Citation2010). Furthermore, racial, ethnic, and class segregations in the United States frequently coincide, with racial minorities predominantly residing in areas often devoid of capital, market, and entrepreneurial resources (Bates et al. Citation2018; Connor et al. Citation2019). This intersection of high nonwhite populations and poverty elucidates why entrepreneurship in underserved communities encompasses both social and spatial dimensions (Wang Citation2021).

The challenges facing entrepreneurs of color and businesses in underserved communities underscore the need to cultivate inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystems to build organizational, service delivery, and advocacy infrastructure that better meets their needs. This necessitates synergistic collaborations among government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and the private sector to connect entrepreneurs and businesses in underserved communities with diverse stakeholders, both within and beyond their local community, to improve the effectiveness of education programs for small businesses owners, and to use multilinguistic, multicultural, and community-based approaches to promote their penetration into nontraditional markets (Wang Citation2022). This renders entrepreneurship and economic development programs that emphasize underserved communities, such as those pursued by NCGrowth, both timely and imperative.

Universities’ Role in Entrepreneurship Ecosystems

An EE consists of a competent labor force, appropriate local cultural outlooks, social networks, investment capital, and active economic policies that offer a range of institutional and infrastructural supports for innovation and entrepreneurship (Spigel Citation2017; Malecki Citation2018; Qian and Acs Citation2022). Key stakeholders for the creation and growth of EEs include entrepreneurs, risk capital investors, universities, large corporations, philanthropist, and government agencies. For example, the government can act as conveners for technology communities and sponsors of local entrepreneurship events to connect various stakeholders and facilitate resource matching for start-up activities, thereby directly accelerating knowledge spillover in entrepreneurship (Feld Citation2020).

Universities are integral to regional economic development and EEs (Audretsch Citation2018). For example, Silicon Valley, Singapore, Bangalore in India, and Zhongguancun in China, although following different paths, have all capitalized on connections between hi-tech firms, local business communities, and HEIs to become globalized hi-tech centers (Chacko Citation2007). A “university-industry-government” triple helix model is often employed to describe the interactions and intermediation between government, industry, and universities (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation2000). Universities, traditionally seen as educational and research institutions, now also function as economic drivers by producing innovation and fostering entrepreneurship. They function as a knowledge hub and intermediator to promote technological innovation, attract capital investment, produce knowledge infrastructure, and incubate an environment for regional development.

Public investment in higher education, under this paradigm, is a way to fuel economic growth and innovation. Therefore, many governments and institutions use this reasoning to legitimize their investments in public higher education. Accordingly, entrepreneurship education programs have proliferated since the 1980s (Solomon Citation2007). Pitching opportunities, access to incubators, training and consulting, funding assistance, and business plan preparation are just a few examples of the ways a university-based entrepreneurship center can support entrepreneurship and business development (Rauch and Hulsink Citation2015). However, despite significant challenges faced by entrepreneurs of color and businesses in distressed areas, university entrepreneurship centers have largely overlooked explicit efforts to promote economic and social equity in underserved communities (O’Brien et al. Citation2019; Bedő et al. Citation2020).

Universities’ Role in Community Networks

HEIs have been playing key roles in addressing local challenges, promoting equity and diversity, and building social capital (Jongbloed et al. Citation2008). Community engagement initiatives orchestrated by universities range from service-learning programs, where students apply their academic skills to real-world community problems, to research projects that directly align with community needs (Bringle and Hatcher Citation2002; Goddard and Vallance Citation2013). Numerous studies highlight that universities play a pivotal role in spearheading the creation of new innovation-led growth hubs in their locales, as well as transforming old areas into unique, place-based business communities and entrepreneurial systems. Beyond this, universities value and advance the social development of their communities through targeted institutional initiatives that address broader quality of life concerns in neighborhoods, encompassing public infrastructure, amenities, socioeconomic conditions, and public services (Addie et al. Citation2015; Mapes et al. Citation2017; Ehlenz Citation2019).

Engaged universities have cultivated robust community-university collaborations in neighborhoods grappling with systemic socioeconomic challenges, including poverty, racial disparities, homelessness, and crime (Allahwala et al. Citation2013). Like their contribution to economic development, engaged universities are intricately woven into multiscaled learning and governance networks. They collaborate with diverse coalitions of state and nonstate actors, acting as pivotal “nodes” adept at aligning external resources and influences with localized needs (Benneworth and Jongbloed Citation2010; Pugh et al. Citation2016). As such, the dual experiences of HEIs in economic advancement and community engagement provide them a unique opportunity to potentially address challenges in promoting entrepreneurship in underserved communities (Hodges and Dubb Citation2012). Consequently, universities, given their extensive experience in championing entrepreneurship, interdisciplinary prowess, state-of-the-art facilities, deep-rooted community engagement traditions, and their unique role bridging top-down governmental and industrial policies with grassroots movements, possess unparalleled strength to spearhead entrepreneurial endeavors in marginalized communities (Blenker et al. Citation2011; Hazelkorn and Gibson Citation2019).

However, the multiplicity of roles can lead to inherent tensions. Within universities, the commitment to socioeconomic progress in marginalized communities can introduce intricacies in balancing these responsibilities (Benneworth and Jongbloed Citation2010; Goddard and Vallance Citation2013). Specifically, championing innovation and entrepreneurship often necessitates a considerable allocation of resources. An excessive emphasis in this direction could inadvertently detract from resources available for community outreach and engagement, potentially sidelining the socioeconomic development agenda. Moreover, the core goals of socioeconomic upliftment in underserved communities might not align well with the objectives of innovation and entrepreneurship initiatives.

Externally, the capacity of universities to affect local development depends crucially on their ability to balance the multiple relationships established between its locale and its stakeholders. Yet, pronounced disparities in organizational objectives and anticipations for collaboration frequently characterize university-industry alliances (Baum Citation2000). Given the decentralized nature of entrepreneurship ecosystems, wherein no singular entity claims ownership or possesses a comprehensive understanding of its functioning, the objectives of various stakeholders may not always be perfectly aligned. Consequently, the governance frameworks and structures governing the ecosystem are critical for its effectiveness (Feld Citation2020; GIID Citation2023).

We posit that the limited engagement of universities in entrepreneurial activities within underserved communities stems from these internal and external dynamics. In this context, NCGrowth offers a unique and timely opportunity to scrutinize the role of universities within an expansive partnership network, the interconnections among diverse stakeholders, and their interactions with the local communities.

Data and Methodology

NCGrowth

Research Triangle Park (RTP) in North Carolina exemplifies successful public-private partnerships in the United States (Link and Scott Citation2003) that covers the geographic area defined by a triangle with its three points at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina State University in Raleigh, and UNC in Chapel Hill. As the largest research park in the United States—both in terms of employees and acreage—RTP is well known as a place that has successfully developed a thriving entrepreneurship ecosystem with lasting economic impacts (Menzel et al. Citation2017). However, just beyond the prosperous RTP are communities that have been struggling for opportunities and economic development. For most of the twentieth century, the state’s economy relied heavily on furniture, textiles, and tobacco. As these industries declined, many small towns faced significant challenges. Economic distress also disproportionately impacted certain racial and ethnic communities, with Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities reporting higher rates of poverty and unemployment, and lower rates of business growth. For example, the current poverty rate among the white population is 9.4 percent, compared to 21.5 percent among African-Americans, and 26.5 percent for the Indigenous population.

Established at UNC in 2012, NCGrowth operates with the mission “to build an economy with opportunities to prosper for all.” NCGrowth provides technical assistance to businesses, local and state governments, universities, hospitals, and military bases to create jobs and wealth in economically distressed communities. The center is dedicated to generating applied research and pioneering policies that champion equitable development. Additionally, it hosts gatherings and workshops that cut across sectors. Distinguishing itself from many entrepreneurship and regional development centers, NCGrowth’s endeavors are predominantly channeled toward economically distressed areas. These areas are marked by elevated unemployment and poverty rates. Over 90 percent of NCGrowth’s initiatives are centered on such regions, with approximately 40 percent of their business-focused efforts directed toward aiding Black and Indigenous clients, while 50 percent cater to female clients. While a portion of their research and events may have a national scope, their core technical assistance activities for businesses are primarily conducted in North Carolina and South Carolina.

Most of NCGrowth’s activities are organized around projects for business and community clients. These projects involve strategic planning, financial analysis, industrial engineering, asset assessment, market analysis, agribusiness development, business retention strategies, and the establishment of entrepreneurship ecosystems. Clients receive weekly communications, multiple face-to-face meetings with the project team, and a substantial commitment of time—ranging from 150 to 600 or even more hours—devoted exclusively to each individual project. Between 2012 and 2019, NCGrowth completed 164 projects for businesses and 95 projects for communities. The scope of business clients served has encompassed a spectrum of sizes and industries, as detailed in supplementary File 1.

Quantitative Data Collection

Using a list of projects initiated between January 2013 and June 2019, NCGrowth staff retrospectively identified the partners involved in each project, providing a final database of 149 projects. Using this, we identified how the partners had provided support to each project. We classified assistance into three forms: technical assistance, which included expert knowledge, reports, informational websites, databases, expert personnel, and technical feedback; financial support, which included grants, loans, and equity financing; and other types of support, such as free workspace, advertising, nontechnical staff, and organization for meetings or events.

The same participants could have played different roles in different projects. For example, a client could have become a community partner in a later project. Altogether we identified 431 participants from the database, and these could be classified into eight types: bank/funder (B/F), government (G), nonprofit (N), private company (P), religious organization (R), small business development center (S), university (U), and other (O). presents the different types of participants, of whom 37.4 percent were private companies, 25.3 percent government entities, and 19.0 percent nonprofit organizations. Additionally, 70.2 percent of participants had acted as project partners, 24 percent as project clients, and 5.8 percent as both project partners and clients.

Table 1 The Number of Different Types of Participants

The Construction and Measurement of Partnership Networks

A social-network analysis (SNA) approach was useful for investigating actors and connections between elements of the partnership network. An SNA approach has been widely used in the field of social sciences (Wasserman and others 1994) to address network organization issues and to understand how different roles played in organizational networks can affect cooperation on projects (Yustiawan and others 2015). Connectivity between organizations in an entrepreneurship ecosystem can range from sharing information to undertaking joint projects and cooperating on governance. In our study, all the clients and partners in the NCGrowth-led partnership, except for NCGrowth itself, had acted as “nodes,” and we defined the links among the participants as “edges.” The strength of the link between two nodes was measured by the frequency with which the partners were involved in the same projects. We used two indicators (details available upon request) to describe the roles of certain participant types in the partnership networks:

One indicator was degree centrality (DC), which reflected the importance of a certain node in a network. The greater the degree centrality, the more important the node.

The second indicator was betweenness centrality (BC), which reflected the extent to which a certain node could control the connections among other nodes. The greater the degree of the betweenness centrality, the stronger the controlling role and the higher the network status for the node.

Qualitative Data Collection and Analyses

With the assistance of NCGrowth, we recruited interview participants from past projects, securing a final total of 10 small business clients and 14 community partners whom we interviewed between September 2020 and July 2021. The business clients were randomly chosen from the client database, and interviews with them focused on their experience of business development and interaction with stakeholders in the regional entrepreneurship ecosystem. The community partners were chosen through a purposive sampling strategy to reflect the different sectors in the partnership. Their interviews focused on their experiences of working with small businesses, NCGrowth, and other partners. Supplementary File 2 indicates the composition of interview participants across the sectors and their aliases. Each interview lasted for 30–100 minutes. Within each group (business clients or community stakeholders), each participant was presented with the same set of open-ended questions. The interviews were conducted in English via Zoom or phone, were audio recorded with the participants’ agreement, and were later transcribed verbatim for analysis. Aliases were used in the findings.

In addition, we collected data from virtual events organized by NCGrowth. These events included social networking sessions among entrepreneurs and community stakeholders, showcasing local businesses of their innovative activities, and focus group discussions on community building and regional development among the community stakeholders. Expanding the information we drew from our small number of interviews, this publicly available data provided real-time, lived experiences of the business owners and their interaction with local communities. Twenty-three document data files in video format involving more than 90 participants were analyzed (Supplementary File 3 shows the sources of document data).

Findings and Discussion

Structure of the Networks

Although NCGrowth had initiated all the projects used in the study, the partnerships created had been extended to involve a much larger group of universities. lists the top ten participants in terms of their degree centrality (DC) and betweenness centrality (BC). For each indicator, six out of the top ten participants are HEIs. This suggests that universities form key pillars of cooperation, as control centers, in this type of entrepreneurship network, which in turn affects the links among other types of participants.

Table 2 The Top ten Participants in Terms of Degree Centrality and Betweenness Centrality

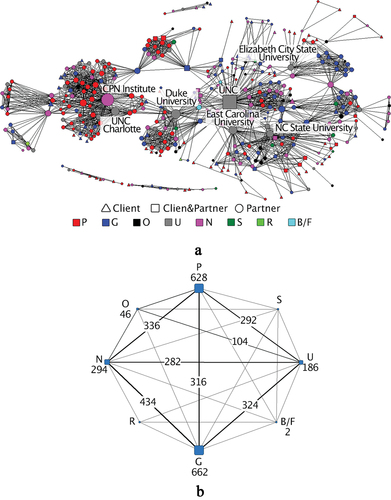

To better reflect the structure of the network and the relationships among different types of participants, depicts the network at the individual-participant level. In this figure, the three shapes of the node correspond to the roles played by participants in the network (i.e., client, partner, and client and partner), and the eight colors of the node represent the different types of organization to which each participant belongs. The figure clearly shows universities dominating the network, which is in line with the findings in . For example, in , UNC has the highest degree centrality, as it is connected with 89 participants, followed by CPNI Institute, which is connected with 78 participants.

In we further aggregate the nodes by showing eight sectors where the size of the node represents the number of collaborations among the same type of organization; and the thickness of the line is proportional to the number of collaborations between two different types of organization. For instance, there are 662 connections between different government organizations and 434 connections between government and nonprofit organizations. For connections within the same sector, we can see that most connections exist within government (G-662) and private companies (P-628), followed by nonprofit organizations (N-294) and universities (U-186). By comparison, connections between banks/funders (B/F-2) and small business centers (S-0) are quite limited. This is different from the structure when measured at the individual-participant level, where universities dominate the networks. The difference indicates that, although a partnership may be initiated by one university, collaborations are formed much more broadly across different sectors.

The pattern is consistent with a large literature that highlights the role of universities as knowledge hubs and facilitators of regional entrepreneurship ecosystems (Audretsch Citation2018; Malecki Citation2018). Furthermore, universities have established connections with all the other types of organizations, that is, it is they that have the most diversified connections. For example, UNC-CH had a total of 83 links with other participants, with 33 links associated with sector G, 27 links with sector N, 13 links with sector P, and 10 links with other sectors. It is also worth noting that the total number of collaborations associated with universities (1009) is quite close to the number associated with private companies (1033), although the number of universities (35) among the 430 participants is much smaller than the number of private companies (161).

Another key point is the significant role of government (Motoyama and Knowlton Citation2016). Compared to other types of organizations, government ranks first in the number of collaborations associated with nonprofit organizations (434) as well as universities (324), and second in the number associated with private companies (316). The interview data showed why government agencies tended to work with universities. For instance, Holly commented, “EDA has been really pushing for a long time about the benefits of leveraging the assets of universities or institutions of higher education to cultivate economic development and economic opportunity, especially in [the] more distressed areas that often surround economic or economic asset or anchor institutions, such as universities. And that’s one goal. But the other goal is, we also see a lot of benefit in the knowledge base, and the expertise, of those that are at the university, and the problem solving and research they often undertake, their being connected to real-world problems” (Holly, federal government).

Overall, our case study highlights several characteristics: first, extensive collaboration among higher education institutions, with the partnerships led by NCGrowth encouraging a large number of both public and private universities in the region to form a consortium for regional economic development; second, the role of the state, with universities and government agencies working closely to overcome disciplinary and organizational boundaries and facilitate collaboration among multiple stakeholders in underserved communities; third, less intensive connections generated among businesses, or among businesses and universities. The general pattern suggests that the relationship between universities and governments in our case is somewhat different from the Triple Helix model (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff Citation2000) or the theoretical model suggested by Wang (Citation2021), where the inputs of government, HEIs, and industry are more evenly balanced.

Connections among Stakeholders

The expert knowledge provided by NCGrowth was the key to collaboration. “The ability to leverage the intellectual knowledge, the standing, the reputation of the UNC, which is, you know, one of the best public universities in the country, and bring that to bear on problems faced by rural communities” (Jude, consultant). This opinion was echoed by the federal government representative quoted above, “Their ability and collaboration with other neighboring institutions, and connection with communities, especially eastern North Carolina, that has been so hard hit by disasters, you know, really puts them in a unique place to understand kind of the challenges being faced on the ground, to understand key and emerging research and data, and to offer analysis and information that is practitioner-oriented, accessible, and actionable, to those who get it” (Holly, federal government).

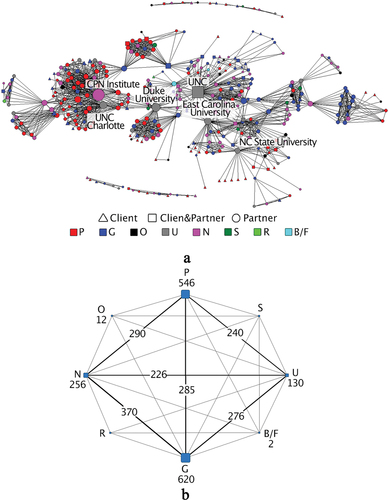

As indicated earlier, the connections among the stakeholders are classified into three types: technical assistance, financial support, and others. presents the top ten participants measured by the two indicators (DC and BC) in terms of technical connections. Half of the top ten participants, according to each indicator, are universities, including UNC-CH, Duke University (DU), East Carolina University (ECU), UNC Charlotte, and NC State University (NCSU).

Table 3 The Top ten Participants in Terms of Degree Centrality and Betweenness Centrality in the Technical Collaboration Network

The overall picture is depicted in This suggests that most organizations are connected through the provision of technical assistance, with universities as the dominant sector. The five universities mentioned above have cooperated with a total of 194 other participants. They have 79 connections with the private sector, 64 connections with the government sector, and 56 connections with the nonprofit sector. At the same time, the government also plays a significant role. The total number of collaborations associated with government agencies (989) and that between government agencies (620) are both the largest.

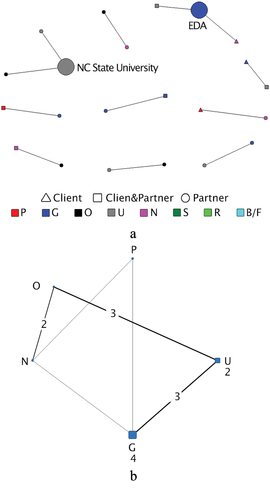

Network analyses also revealed the limited number of connections occurring through the provision of financial support. provides the top two participants measured by the two indicators (DC and BC) in terms of financial connections. NC State University and the federal government agency EDA top the list for both indicators. Compared to technical connections (), the network structure of financial connections is much sparser, as the total number of financial institutions in the partnership is extremely limited; moreover, most financial institutions in the partnership did not produce real financial connections in the network. In addition, the significance of universities has decreased as they are no longer the key control centers in the network of financial connections.

Table 4 The Top Two Participants in Terms of Degree Centrality and Betweenness Centrality in the Financial Collaboration Network

As presented in , the financial collaboration network fails to establish connectivity via the universities, even though these account for nearly one-third of network participants. suggests that some types of organization, including banks/funders, religious organizations/churches, and SBDCs, are not involved in the financial collaboration network. It is also worth noting that this network seems only rarely to facilitate the provision of financial support by banks and SBCs to other organizations. This may be related to the very small sample size of financial institutions and the focus of the program on providing technical assistance to clients rather than financial support. Our interviews also indicated that the involvement of traditional financial institutions was limited. As a university center director commented, “There are not many banks who are directly involved in projects. We partner with them in other ways, and [though] they often attend events … ” (Matt, university). In other words, banks attending events did not necessarily bring in financial support through the center.

Overall, these patterns suggest that technical assistance dominates the collaborations between partners. Both HEIs and government agencies have actively tapped into HEIs’ advantages in knowledge and community connections. Connections relating to the provision of financial support, however, are extremely limited. Access to financial support has long been a challenge for minority entrepreneurship (Bates et al. Citation2018), although few studies have empirically examined this issue from a partnership perspective. Our findings suggest that for universities to foster entrepreneurship ecosystems in underserved communities, they need to engage more resources to strengthen EMOB’s access to finance and wider markets. Universities’ traditional intermediary role as knowledge hubs is not enough. We will discuss this issue later.

Interaction with Underserved Communities

Partnerships Forged by the Needs of Underserved Communities

When talking about the motivation for partnership, most community stakeholders from regions with majority-minority populations immediately mentioned the challenges facing small businesses because small towns lacked “the resources, the capacity, and the cash position” (Max, private). Business owners provided numerous examples to demonstrate the difficulties facing people of color trying to start and grow businesses in their region, and these included lack of funding and wealth; limited business management knowledge; lack of basic skillsets in tax, accounting, business planning, and marketing strategies; constrained time; and lack of visionary leadership, networks, role models, and mentors. As a private business accelerator put it, “I think female and minority entrepreneurs have even more problems because […] the network isn’t as strong for the communities, as well as the funders, the banks, the private equity groups, everybody else, disproportionately” (Blaire, accelerator).

At the community level, there was a lack of basic infrastructure and resources for entrepreneurship. For instance, the accessibility and affordability of broadband was a critical issue facing local communities. This was in stark contrast to Research Triangle Park, a nearby hub of resources for hi-tech entrepreneurship. Consequently, the local communities were left with a limited number of “necessity entrepreneurs” (Jude, consultant) who operated with very limited capacity and had no potential to scale up. Over time, these communities’ ability to build an entrepreneurship ecosystem became increasingly fragile. “So you end up not being able to compete or keep some of your really awesome entrepreneurs who are doing cool stuff because they go to where the resources, where the venture capitalists are. How do we build those resources ourselves and create our own ecosystem within the Burlington Alamance County area that can provide that level of service, can be localized, and can keep people where they want to live and be? That’s one of my big challenges” (Paul, local government).

Participants also noted significant regional disparities in accessing financial capital for entrepreneurship. For example, business owner Tina commented on the huge disparity between her community and RTP, with its hi-tech center, “I am in Eastern North Carolina, and we are not a hub for anything. […] All the money stops at Raleigh. It doesn’t go any further than that. And this is a very important point and I hope you’ll put it in bold: the money stops at Raleigh […] We have an office here called MWEB, minority women in business entrepreneurship or something that’s run through the city. Do you know, that their budget is $10,000 annually, out of the city’s $80 million budget, [this is all that is] allocated to improving minority businesses? So, what you have here is geography. That is a problem. And you have, um, municipalities who simply do not care about investing in minorities. And then they wonder why they cannot win the dollars to get investment” (Tina, Biz-5).

Hence, the scope of NCGrowth’s “entrepreneurship projects” extended beyond mere business startups and acceleration, including a broader perspective of community capacity-building, such as constructing community sidewalks, establishing the groundwork for youth summer camps, and enhancing broadband infrastructure. One illustrative case involves Blaire, who spearheaded a private business accelerator. Blaire directed a private business accelerator. On one front, he collaborated with minority business owners to establish inclusive spaces and identify appropriate services tailored to the Latinx community’s needs, thereby overcoming language barriers. He also supported a Black founder in constructing a mentor network comprised of fellow Black founders. Simultaneously, Blaire participated in community-level capacity enhancement, such as collaborating with local government bodies to devise strategies for improved broadband connectivity. He came to NCGrowth for help.

To address these multifaceted objectives, NCGrowth took the initiative to conceptualize and execute projects, select suitable partners, and progressively foster collaborations among various regional universities, state and local government agencies, community-based organizations, and private sector entities. This collective effort was underpinned by a shared comprehension of local community challenges, particularly those pertinent to racial minorities, poverty, and resource scarcity. Importantly, this coalition also shared a collective sense of community and was unified in their belief that community-based solutions were imperative.

The Challenges of Engaging Local Communities

The stakeholders interviewed pinpointed several factors leading to a successful collaboration (Supplementary File 4). Central to these is a deep understanding of local communities and the alignment of shared objectives. Transparent communication, coupled with a responsive approach, is indispensable. Further determinants of successful collaboration encompass funding, leadership, and operational capacity; each of these plays a significant role in achieving shared goals, enhancing communication effectiveness, and fortifying trust. Notably, these factors underscored the engagement with small businesses as the primary challenge in forming partnerships. While the aim of such partnerships was to cultivate an entrepreneurial ecosystem, initiate new businesses, and nurture their growth, many of these enterprises found themselves entangled in day-to-day operations. Consequently, they often failed to recognize the value of investing time and resources in partnership undertakings, despite their pressing needs for business management acumen, financing, and market expansion. One business consultant said, “Usually, you need that one person to sit down with you for an extended amount of time to really get it, […]. It’s usually the hardest thing to get” (Austin, consultant). Likewise, Paul said, “they’re so focused on trying to maintain their business, keep their heads above water, that they don’t have time for me, or for the person trying to get them capital or everything else. […] I can be, you know, the best marketer in the world, but people still have to pick up the phone or want to do something when I call and reach out to them” (Paul, local government).

Service providers emphasized the importance of bringing local communities at the decision-making table. As one Federal Economic Development Agency representative commented, “There is no economic development project that is able to be undertaken by a single economic developer. This is truly a team sport. […] There’s often the second thing, I think,[which] is the willingness to have robust conversations with the community broadly and understand what the community needs and the projects being solved […] The community represents the entire community, and there’s equity in terms of who’s around the table. It’s not just a single player” (Holly, federal). This aligns with the call from researchers for policy makers to prioritize the voices of entrepreneurs in entrepreneurship ecosystems building (Qian and Acs Citation2022). Notably, in this context, “local communities” encompass a scope wider than just start-up companies. Yet, navigating the path to achieving this objective remains a formidable challenge.

Another challenge came from university’s long-term engagement with local communities. The interviewees provided numerous examples of benefits brought by projects in community development and capacity building, ranging from a barbershop where parents could drop their kids off after school, to campus meal programs purchasing locally grown food. However, a key issue was the extent to which, and duration for which, university centers could engage local communities. There was often a lack of “the local building-block people.” As Bruce pointed out, after the university team left, the community was left with a proposed action plan, “then those plans kind of get pushed to the wayside, because you’ll have other issues that come up in a small community, you know, sewage, water, and those things have to be addressed right away.” Also, when there were changes of leadership among the stakeholders, “all the work you’ve done with those elected officials dissipates, and then you start again, and that’s very difficult” (Bruce, nonprofit).

One staff member at NCGrowth talked particularly about the nature of their community work, “In some ways, we are a poor fit for a research university because we work for communities. We do not work for the purpose of generating publications. We often hear people at universities talking about how to engage communities when they have such a bad rap for doing research, collecting data, and leaving. But we never have that problem because we collect data for our clients” (Matt, university). Still, as expressed by a local partner, engagement could be a general challenge for university programs, “Sometimes institutions come in, they grab data, and they leave. And I think that’s something that a lot of institutions are working on, mitigating, you know, we don’t want just that. We want to establish meaningful relationships, continual relationships with community members” (Jackie, private).

Insights from both business clients and regional stakeholders highlight two key dimensions: (1) Unlike conventional technology- and growth-oriented innovation and entrepreneurship that is focused on establishing economically prosperous enterprises, fostering entrepreneurship in underserved communities is driven by a comprehensive objective to enhance living conditions, improve education, and generate opportunities for both community advancement and business development (Benneworth and Jongbloed Citation2010; Goddard and Vallance Citation2013). (2) Universities are then confronted with the intricate task of resource allocation between innovation, economic growth, and community engagement, alongside building collaborations with industries and governments across both national and international fronts. Navigating these multifaceted demands often presents a distinct set of challenges (Baum Citation2000; Feld Citation2020; GIID Citation2023).

Discussion and Conclusion

The institutional barriers, culture, and resource scarcities in underserved communities present a particular set of constraints for entrepreneurship (Rubin Citation2010; Bedő et al. Citation2020). The partnerships led by NCGrowth to foster entrepreneurship in underserved communities suggest several points for discussion. First, connections among stakeholders are not even, with universities and government agencies being more dominant than other players. This reflects that universities have strong advantages in knowledge transfer through a wide variety of mechanisms, and as such, both the university and government function as strong facilitators by taking advantage of universities’ technological expertise and community relationships. However, there may be more redundancy in such facilitation and less long-term engagement at the level of community practice, and more technological connections but less financial supports for underserved communities. The unevenness suggests a need for the involvement of more anchor institutions—hospitals, big corporations, religious organizations, philanthropists, and so on—in the regional partnerships.

Second, NCGrowth’s experiences underscore that fostering an entrepreneurship ecosystem in underserved communities is based on goals that are aligned not only to increase the microlevel growth of supported firms but also to enhance the macrolevel entrepreneurship environment of the region. This advocates for an integrative, collaborative strategy that establishes incentives and frameworks connecting knowledge with other vital ecosystem components (Russo et al. Citation2007). As such, university entrepreneurship initiatives are not solely about creating new companies; rather, they encapsulate a broader spectrum of social processes geared toward bolstering the holistic socioeconomic welfare of communities. Crucial to these processes is an inclusive approach to policy formulation and execution. Research has argued that governance systems and structures determine who sits at the table and is empowered to help make decision in building the regional entrepreneurship ecosystems. Therefore, it is important to design governance structures that identify and convene a core set of inclusive and representative local and regional stakeholders, as well as listen to what they see as the value proposition to advancing regional entrepreneurship ecosystems (GIID Citation2023). The communities with the most pressing needs should be empowered to articulate their requirements, guiding universities on how best to deploy their resources to bridge community gaps.

Third, economic development and innovation policy should be integrated with social policy to address disparities in entrepreneurship across social groups and communities. Local policy makers have advanced a wide range of policy and planning agenda items in recent years to tackle issues like housing, immigration, and economic development (Spicer and Casper-Futterman Citation2020). These policies can be integrated to expand support for socioeconomically disadvantaged areas. EMOBs not only play a growing role in the urban economy but also serve as an important source of community development and neighborhood revitalization (Liu et al. Citation2014; Zhuang Citation2021). Incentivizing the developmental role of universities in connecting people-based and place-based programs remains an unexplored area. In their unique role, universities could provide both conceptual and practical means to expand the idea of traditional economic development to encompass community economic development, workforce development, and policy focused on enhancing the economic contributions of poor people.

Fourth, in our case study, the financial support network was very limited and almost 100 percent publicly backed in underserved communities. This suggests a need for a more differentiated approach to developing financial support networks in both the amount of finance and the specialized strategy support that can be provided. There may also be a need to stimulate cross-region venture capital provision, especially considering the strong entrepreneurship ecosystem in nearby RTP. A potentially fruitful avenue would be to consider how to stimulate cross-regional mobility in equity funding provision, from the RTP to its surrounding smaller towns and distressed regions, by identifying enough sufficiently attractive targets in underserved communities; or by helping entrepreneurs in these communities with ventures that may be potentially attractive to venture capital firms and business angels to signal their quality to financiers located outside their region.

Last, at the university level, programs on entrepreneurship education, economic development, and community engagement could be more integrated. Traditionally narrow policies and practices aimed at optimizing the economic function of universities may have downplayed universities’ production of the soft infrastructure of local urban economies and global innovation—that is, the potential impact of low monetary value but high societal impact innovations (Benneworth and Jongbloed Citation2010; Addie et al. Citation2015). NCGrowth’s experience suggests that by creatively using their scientific knowledge, universities can work as engaged community players to empower disadvantaged groups through entrepreneurship. However, the formation and function of partnerships are highly contingent on local communities and long-term engagement, and a willingness to engage in development plans at the community level.

This study has several limitations that warrant further research. First, there is a deficiency of data. Due to the disruption and changes caused by the pandemic, we covered only the projects before the pandemic. Some partners, particularly from earlier projects, may have been inadvertently omitted due to incomplete data collection at the time of project completion. Data limitations include partners’ involvement being forgotten, partner relationships being underestimated due to missing details, and difficulties in attributing individual partners to their associated institutions (considering factors like individuals contributing independently or moving between institutions). Furthermore, the lack of documentation and systematic evaluation of practices by university centers makes data collection extremely cumbersome. Second, while the indicators generated from the social-network analyses identify the structural unevenness of the university-led entrepreneurship ecosystem, they do not offer insights into the factors shaping these patterns. Though in-depth interviews shed light on the process of partnership functions, the absence of data at each participant level in the partnership prevents quantitative analyses of how the partnerships form and function over time. Additionally, it is essential to note that this study is just one case study, and its applicability to other similar university programs or programs without a focus on underserved communities remains unknown. To address these gaps, future empirical research should make efforts to investigate these topics thoroughly.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.7 KB)Acknowledgments

Special thanks extend to the businesses and community stakeholders who graciously devoted their time and shared their invaluable experiences. Reyna Peña-Calvillo offered invaluable research assistance for data collection. Alyse Polly provided helpful feedback on early drafts of the manuscript. The ultimate rendition of this article has been enriched by the insightful feedback from the Editor and the anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00167428.2023.2256000.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addie, J.-P. D., R. Keil, and K. Olds. 2015. Beyond Town and Gown: Universities, Territoriality and the Mobilization of New Urban Structures in Canada. Territory, Politics, Governance 3 (1):27–50. 10.1080/21622671.2014.924875

- Allahwala, A., S. Bunce, L. Beagrie, S. Brail, T. Hawthorne, S. Levesque, J. V. Mahs, and B. S. Visano. 2013. Building and Sustaining Community-University Partnerships in Marginalized Urban Areas. The Journal of Geography 112 (2):43–57. 10.1080/00221341.2012.692702

- Audretsch, D. B. 2018. Entrepreneurship, Economic Growth, and Geography. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 34 (4):637–651. 10.1093/oxrep/gry011

- Bagchi‐Sen, S., and H. L. Smith. 2012. The Role of the University as an Agent of Regional Economic Development. Geography Compass 6 (7):439–453. 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00497.x

- Bates, T. 2006. The Urban Development Potential of Black-Owned Businesses. Journal of the American Planning Association 72 (2):227–237. 10.1080/01944360608976741

- Bates, T., W. D. Bradford, and R. Seamans. 2018. Minority Entrepreneurship in Twenty-First Century America. Small Business Economics 50 (3):415–427. 10.1007/s11187-017-9883-5

- Bates, T., J. Farhat, and C. Casey. 2022. The Economic Development Potential of Minority-Owned Businesses. Economic Development Quarterly 36 (1):43–56. 10.1177/08912424211032273

- Baum, H. S. 2000. Fantasies and Realities in University-Community Partnerships. Journal of Planning Education and Research 20 (2):234–246. 10.1177/0739456X0002000208

- Béchard, J.-P., and D. Grégoire. 2005. Entrepreneurship Education Research Revisited: The Case of Higher Education. Academy of Management Learning & Education 4 (1):22–43. 10.5465/amle.2005.16132536

- Bedő, Z., K. Erdős, and L. Pittaway. 2020. University-Centred Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in Resource-Constrained Contexts. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 27 (7):1149–1166. 10.1108/JSBED-02-2020-0060

- Benneworth, P., and B. W. Jongbloed. 2010. Who Matters to Universities? A Stakeholder Perspective on Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Valorisation. Higher Education 59 (5):567–588. 10.1007/s10734-009-9265-2

- Blenker, P., S. Korsgaard, H. Neergaard, and C. Thrane. 2011. The Questions We Care About: Paradigms and Progression in Entrepreneurship Education. Industry and Higher Education 25 (6):417–427. 10.5367/ihe.2011.0065

- Bringle, R. G., and J. A. Hatcher. 2002. Campus–Community Partnerships: The Terms of Engagement. Journal of Social Issues 58 (3):503–516. 10.1111/1540-4560.00273

- Casey, C. 2012. Low-Wealth Minority Enterprises and Access to Financial Resources for Start-Up Activities: Do Connections Matter? Economic Development Quarterly 26 (3):252–266. 10.1177/0891242412452446

- Chacko, E. 2007. From Brain Drain to Brain Gain: Reverse Migration to Bangalore and Hyderabad, India’s Globalizing High Tech Cities. GeoJournal 68 (2–3):131–140. 10.1007/s10708-007-9078-8

- Connor, D. S., M. P. Gutmann, A. R. Cunningham, K. K. Clement, and S. Leyk. 2019. How Entrenched is the Spatial Structure of Inequality in Cities? Evidence from the Integration of Census and Housing Data for Denver from 1940 to 2016. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 110 (4):1022–1039. 10.1080/24694452.2019.1667218

- Drucker, J. 2016. Reconsidering the Regional Economic Development Impacts of Higher Education Institutions in the United States. Regional Studies 50 (7):1185–1202. 10.1080/00343404.2014.986083

- Ehlenz, M. M. 2018. Defining University Anchor Institution Strategies: Comparing Theory to Practice. Planning Theory & Practice 19 (1):74–92. 10.1080/14649357.2017.1406980

- Ehlenz, M. M. 2019. Gown, Town, and Neighborhood Change: An Examination of Urban Neighborhoods with University Revitalization Efforts. Journal of Planning Education and Research 39 (3):285–299. 10.1177/0739456X17739111

- Etzkowitz, H., and L. Leydesdorff. 2000. The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations. Research Policy 29 (2):109–123. 10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

- Fairlie, R., and A. M. Robb. 2008. Race and Entrepreneurial Success. Cambridge, MA. The.[Is there more to be added here?

- Feld, B. 2020. Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- GIID. 2023. Why Governance Matters: An Analysis on How Innovation Districts ‘Organize for Success’. The Global Institute on Innovation Districts (Blog). https://www.giid.org/why-innovation-districts-need-effective-governance/.

- Goddard, J., and P. Vallance. 2013. The University and the City. New York: Routledge.

- Harper-Anderson, E. 2019. Contemporary Black Entrepreneurship in the Professional Service Sector of Chicago: Intersections of Race, Entrepreneurship, and Economic Transformation. Urban Affairs Review 55 (3):800–831. 10.1177/1078087417712035

- Hazelkorn, E., and A. Gibson. 2019. Public Goods and Public Policy: What is Public Good, and Who and What Decides? Higher Education 78 (2):257–271. 10.1007/s10734-018-0341-3

- Hodges, R. A., and S. Dubb. 2012. The Road Half Traveled: University Engagement at a Crossroads. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

- Isenberg, D. J. 2010. How to Start an Entrepreneurial Revolution. Harvard Business Review 88(6):40–50.

- Jongbloed, B., J. Enders, and C. Salerno. 2008. Higher Education and Its Communities: Interconnections, Interdependencies and a Research Agenda. Higher Education 56 (3):303–324. 10.1007/s10734-008-9128-2

- Link, A. N., and J. T. Scott. 2003. The Growth of Research Triangle Park. Small Business Economics 20 (2):167–175. 10.1023/A:1022216116063

- Liu, C. Y., J. Miller, and Q. Wang. 2014. Ethnic Enterprises and Community Development. GeoJournal 79 (5):565–576. 10.1007/s10708-013-9513-y

- Malecki, E. J. 2018. Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Geography Compass 12 (3):e12359. 10.1111/gec3.12359

- Mapes, J., D. Kaplan, V. K. Turner, and C. Willer. 2017. Building ‘College Town’: Economic Redevelopment and the Construction of Community. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 32 (7):601–616. 10.1177/0269094217734324

- Menzel, M.-P., M. P. Feldman, and T. Broekel. 2017. Institutional Change and Network Evolution: Explorative and Exploitative Tie Formations of Co-Inventors During the Dot-Com Bubble in the Research Triangle Region. Regional Studies 51 (8):1179–1191. 10.1080/00343404.2016.1278300

- Motoyama, Y., and K. Knowlton. 2016. From Resource Munificence to Ecosystem Integration: The Case of Government Sponsorship in St. Louis. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 28 (5–6):448–470. 10.1080/08985626.2016.1186749

- O’Brien, E., T. M. Cooney, and P. Blenker. 2019. Expanding University Entrepreneurial Ecosystems to Under-Represented Communities. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy 8 (3):384–407. 10.1108/JEPP-03-2019-0025

- Pugh, R., E. Hamilton, S. Jack, and A. Gibbons. 2016. A Step into the Unknown: Universities and the Governance of Regional Economic Development. European Planning Studies 24 (7):1357–1373. 10.1080/09654313.2016.1173201

- Qian, H., and Z. J. Acs. 2022. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Economic Development Policy. Economic Development Quarterly 37(1):96–102 December 10.1177/08912424221142853

- Rauch, A., and W. Hulsink. 2015. Putting Entrepreneurship Education Where the Intention to Act Lies: An Investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning & Education 14 (2):187–204. 10.5465/amle.2012.0293

- Rubin, J. S. 2010. Venture Capital and Underserved Communities. Urban Affairs Review 45 (6):821–835. 10.1177/1078087410361574

- Russo, A. P., L. V. D. Berg, and M. Lavanga. 2007. Toward a Sustainable Relationship Between City and University: A Stakeholdership Approach. Journal of Planning Education & Research 27 (2):199–216. 10.1177/0739456X07307208

- Solomon, G. 2007. An Examination of Entrepreneurship Education in the United States. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development l (2):168–182. 10.1108/14626000710746637

- Spicer, J. S., and E. Casper-Futterman. 2020. Conceptualizing US Community Economic Development: Evidence from New York City. Journal of Planning Education & Research 0739456X2092907010.1177/0739456X20929070

- Spigel, B. 2017. The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (1):49–72. 10.1111/etap.12167

- Wang, Q. 2021. Higher Education Institutions and Entrepreneurship in Underserved Communities. Higher Education 81 (6):1273–1291. 10.1007/s10734-020-00611-5

- Wang, Q 2022. Planning for an Inclusive Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: COVID-19 and Business Resilience in Underserved Communities. Journal of the American Planning Association 1–1510.1080/01944363.2022.2105740

- Zhuang, Z. C. 2021. The Negotiation of Space and Rights: Suburban Planning with Diversity. Urban Planning 6 (2):113–126. 10.17645/up.v6i2.3790