?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The role of company standards as a strategic tool for the optimisation of internal processes and governance of inter-firm relationships has only recently received researchers’ attention. This paper adds to the very limited body of literature by providing empirical evidence of the motives to implement company standards in general and their importance in corporate groups in particular. Using data on German companies active in standardisation, the empirical analysis confirms that companies that are part of a corporate group utilise a higher number of company standards than single firms. By codifying and transferring company-specific information, internal standardisation enhances legal security, productivity, and quality. In particular for corporate groups, internal standards additionally play a crucial role in the realisation of technical interoperability, which facilitates the development and management of internal platforms. The data, therefore, provides empirical evidence that standardisation can be used as a tool to improve efficiency and communication, and thereby facilitate global governance of multinational firms.

1. Introduction

As globalisation grows, firms aim to increase their production volumes through exporting, which eventually increases revenue and fosters productivity improvements through the exploitation of economies of scale and scope. An alternative way to adapt to the rapid globalisation is the development of complex international strategies such as outsourcing and foreign direct investment. Possible motivations for a ‘slicing up of the value-chain’ (Krugman Citation1995) are according to Dunning (Citation1993) access to markets (market seeking) and resources (resource seeking), as well as cost reductions (efficiency seeking).

The costs of market transactions as compared to internal transactions determines whether it is more beneficial to perform different stages of the value-chain in-house or through external partners (Coase Citation1937). Outsourcing to external business partners at home or abroad is beneficial if products and processes are characterised by a high degree of market compatibility and low amount of company-specific knowledge. Interoperability between different products in the market can be realised through the development of standards in informal consortia or formal standard-setting organisations. Formal standards are generally not specific to one company but provide access to industries or regions for all market players (Blind Citation2004). Participation in public standardisation activities reduces the level of differentiation between products of competing firms and comes with the risk of inadvertently revealing proprietary information (e.g. Blind Citation2006).

If technologies and business practices convey knowledge that is of value to firms, they seek to keep related value-chain activities in-house (Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon Citation2005). This can be achieved by either producing as a single firm in one or multiple locations or by establishing a network of specialised, but legally separate firms that are subject to common control by the parent firm. So called corporate groups have to be differentiated from independent firms that enter into strategic alliances. The establishment of an internal company network creates complex interfaces. The complexity of corporate governance increases the dispersion of international operations. A conglomeration of firms not only expands their product portfolio, but also creates a need to integrate different corporate cultures and management systems. Integrating value-chain activities worldwide and coordinating internal interfaces create high managing, monitoring, and transaction costs. For Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) that establish subsidiaries abroad challenges especially arise from heterogeneous operating conditions in different countries.

One approach for corporate groups to meet their special need for internal consistency is the application of standards (e.g. Guler, Guillén, and Macpherson Citation2002; Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon Citation2005; Gibbon and Ponte Citation2005; Prakash and Potoski Citation2007; Clougherty and Grajek Citation2008, Citation2014; Kaplinsky Citation2010; Perez-Aleman Citation2011; Gereffi and Lee Citation2012). In particular, the development of company standards, which are generally not available to the public, provides a tool to transfer sensitive, company-specific information between firms of the same corporate group (Sturgeon, van Biesebroeck, and Gereffi Citation2008). However, only a few studies investigate motives for the application of company standards and their role in supply chain governance (e.g. Dowell, Hart, and Yeung Citation2000; Jaffee and Masakure Citation2005; Christmann Citation2004; De Vries, Slob, and van Gansewinkel Citation2006; Fortanier, Kolk, and Pinkse Citation2011; Mellahi, Frynas, and Collings Citation2015: Großmann and von Gruben Citation2014; Großmann, von Gruben, and Lazina Citation2016). Due to a lack of micro data on the application of company standards, the few studies focus on certain industries and insights are, in general, based on case studies. Albeit none of the studies explicitly addresses the application of company standards in intra-firm transactions, their results imply a crucial role of internal standardisation for the governance of corporate groups.

At first, this paper summarises the existing literature on the motives for internal standardisation and draws conclusions on the special role of company standards in corporate groups. These theoretical considerations are presented in the first chapter. The empirical analysis, which is based on data from the German Standardization Panel (GSP), is presented in the second chapter. The data from the surveys conducted among German firms active in formal standard-setting organisations from 2013 to 2016 provides cross-sectional information on the application of different types of standards categories. For the first time, generalised ordered logit models are applied to empirically investigate differences in the utilisation of company standards and the motives depending on the form of business organisation. The empirical analysis confirms that firms which are part of a corporate group utilise a higher number of company standards than single firms. By codifying and transferring company-specific information, internal standardisation enhances legal security, productivity, and quality. For corporate groups, they additionally play a crucial role in the realisation of technical interoperability, which facilitates the development and management of internal platforms. A summary of the results and the conclusion are presented in the last chapter.

2. Motives for the application of company standards

Coordination and control of inter- and intra-firm relationships are crucial for the success of internationalisation strategies. By providing ‘(…) for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines, or characteristics for activities or their results (…)’ (EN 45020), standards reduce transaction costs and facilitate the specialisation of companies on different stages of the value-chain (Swann Citation2010; Blind et al. Citation2018). In contrast to Blind and Mangelsdorf (Citation2016), the focus of this paper is on the motives for internal standardisation and the differences in the application of company standards between firms that belong to a corporate group and single companies.

Standards can be classified depending on their purpose and theme (EN 45020). Based on data from three global German companies, Großmann, von Gruben, and Lazina (Citation2016) conclude that the following types of company standards exist: basic, testing, process, product, material, delivery, quality, and construction standards. The authors also provide an overview of the effects of such standards, which are summarised in the next section. Overall, company standards have two major fields of application: the coordination of inter-firm relationships and the improvement of internal processes.

2.1. External perspective on the application of company standards

Standards can be imposed on business partners in order to increase compatibility of products, quality, and legal security. External standards that do not comprise of firm-specific information can play a significant role in inter-firm relationships. International management system standards, such as ISO 9001 for quality management (e.g. Marucheck et al. Citation2011; Kaplinsky Citation2010) or several others related to supply chain risk management (Blos et al. Citation2016) can be used as tools in the governance of global value-chains. Großmann and von Gruben (Citation2014) discuss the role of company standards in inter-firm relations. Internal standards can be especially relevant to the strengthening of firms’ bargaining position towards both suppliers and customers and the coverage of liability and reputation concerns in integrated value-chains.

Another important factor in the development of a global brand is quality assurance. It increases customer satisfaction and loyalty, thereby improving the global image of the firm and strengthening its reputation (e.g. Christmann Citation2004; Dowell, Hart, and Yeung Citation2000). Hudson and Jones (Citation2003) conclude that the application of the international quality management system standard ISO 9001 is associated with the improvement of internal processes and – according to Huo, Han, and Prajogo (Citation2014) – even innovation in case of their advanced implementation. In contrast, Baake and Schlippenbach (Citation2011) argue that, in order to meet liability and reputation concerns, MNEs apply corporate standards which are of higher quality than market standards. For the example of environmental standards, Dowell, Hart, and Yeung (Citation2000) show that the application of corporate standards that exceed the minimum market standard is related to a higher market value of the firm. Through differentiation from competitors’ products, company standardisation may be a strategic tool to create competitive advantages (Henson and Reardon Citation2005). In corporate groups, internal standards can be used to transfer high-value assets between subsidiaries and facilitate the exploitation of competitive advantages abroad.

Another incentive for firms to develop company standards is to gain first mover advantages in external standardisation processes. That can be achieved when company standards are converted into external standards, such as international standards released by international standardisation organisations (e.g. ISO). If standards that include know-how that is even patented gain wide acceptance in the market, companies will benefits immensely from so-called ‘standard-essential patents’ (e.g. Lerner and Tirole Citation2014).

2.2. Internal perspective on the application of company standards

By decreasing asset specificity (e.g. Argyres and Bigelow Citation2010), standardisation facilitates technical interoperability and thereby fosters modularisation strategies (e.g. Perera Citation2007; Muffatto Citation1999; Mikkola Citation2006) that are associated with the deintegration of value-chain activities. That implies that firm-specific, idiosyncratic knowledge can no longer be used as a source of competitive advantages (Schilling Citation2000). Modularisation through the application of company standards can simultaneously enhance differentiation from competitors’ products (Großmann, von Gruben, and Lazina Citation2016) and efficiency. It facilitates the internal fragmentation of value-chain activities and the development of a high-performance company network.

Firms operating globally seek to increase efficiency by coordinating business activities on a worldwide scale. Standardised products for the global market are centrally managed and Manufactured in large quantities to generate economies of scale. The success of such efficiency-seeking strategy hinges on the joint work of all members of a corporate group towards a defined set of objectives within the global strategy. Internal standardisation can serve as a tool to diffuse company-specific knowledge and technologies between value-chain activities (Sturgeon, van Biesebroeck, and Gereffi Citation2008). It facilitates the harmonisation of product and process specifications and provides a ‘common language’ (Clougherty and Grajek Citation2008) for all intra-firm transactions (Subramaniam Citation2006). Company standards support the development of a high-performance enterprise network with a strong corporate culture (Festing and Eidems Citation2011; Fortanier, Kolk, and Pinkse Citation2011; Dowell, Hart, and Yeung Citation2000; Larsson and Finkelstein Citation1999). The establishment of routines within the firm-specific strategic context foster responsible corporate behaviour, thereby reducing internal transaction costs. Multiple studies conclude that the effectiveness of international management system standards, such as ISO 9001 and ISO 14001, in improving internal processes is limited (e.g. Boiral Citation2003, Citation2007; Ozbugday Citation2019). Internal standardisation can be a better tool to reach this goal. According to Ton and Huckman (Citation2008), the application of internal process standards reduces the negative effects related to turnover, because it limits the loss of knowledge when employees depart by facilitating knowledge diffusion. Furthermore, formalisation through standardisation can enable the monitoring of subsidiaries’ performance (Bartlett and Ghoshal Citation2002; Harzing and Sorge Citation2003; Mellahi, Frynas, and Collings Citation2015). That is especially relevant in MNEs, whose subsidiaries operate in different business environments and cultures.

If preferences vary across customers due to cultural, linguistic, economic or regulatory differences between the home and the host country (Prahalad and Doz Citation1987), firms are confronted with the challenging trade-off between standardisation and adaption (Calantone et al. Citation2004). They may decide to adopt a flexible approach that allows manufacturing to remain responsive to local circumstances, while cost efficiency is maximised through concentrated production, optimal sourcing, and centralised organisational activities. Pressures for responsiveness can lead to incremental innovations (Van Beers and Zand Citation2014), in particular with the involvement of local partners. Subramaniam (Citation2006) reveals empirical evidence for a positive influence of the standardisation-adaptation balance on transnational new product development capability.

Modular strategies and product platforms enable adaption to local demands while economies of scale and scope are still achieved (Langlois and Robertson Citation1992; Simpson Citation2004). Platforms are ‘subsystems and interfaces that form a common structure from which a company can efficiently develop and produce a family of products (…)’ (Gawer and Cusumano Citation2013, 419). Developing and managing internal platforms in line with company-specific strategies is complex task for which company standards are indispensable. Through their application, common practices, routines, and non-person-oriented information transfer processes can be implemented that create system stability (Sturgeon, van Biesebroeck, and Gereffi Citation2008; Festing and Eidems Citation2011; Gawer and Cusumano Citation2013; De Casanove and Lambert Citation2016).

Internal standards help to ‘describe the technological state of the art of the company’ (Großmann, von Gruben, and Lazina Citation2016, 87). Even if knowledge is too ‘sticky’ to be transferred via formal channels, standards can help build the absorptive capacity required to disseminate knowledge (Tallman and Chacar Citation2011; Hansen and Lovas Citation2004). Diffusion of know-how throughout the corporate group has a positive effect on R&D and innovation (Blind Citation2016), in particular process and product innovation (Lorenz, Raven, and Blind Citation2019), and international competitiveness (Jaffee and Masakure Citation2005). As the codification of company-specific competencies and inherent organisational know-how requires a clear understanding of the processes, company standards foster learning and innovation (Bartlett and Ghoshal Citation2002; Kogut and Zander Citation1993; Großmann Citation2015). In addition, Liker, Collins, and Hull (Citation1999) reveal that the use of in-process design controls implemented via internal design standards is positively related to design–manufacturing integration.

By specifying requirements that products and processes must conform with, company standards can be used as a tool for the optimisation of internal processes that is complementary to external regulation and formal standards in increasing legal security and facilitating market access.

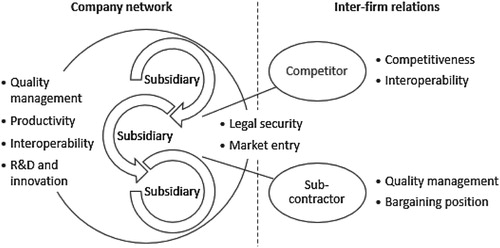

Figure summarises the theoretical considerations regarding the relations between company standards and the governance of company networks and inter-firm relationships. The special role of company standards for corporate groups follows from the integration of fragmented value-chain activities and interdependencies between subsidiaries. Integration will be profitable only if internal interfaces are optimally coordinated, advantages fully utilised and assets kept within the boundaries of the firm. The application of company standards can facilitate the achievement of those goals, as they diffuse company-specific information within but not out of the corporation (Sturgeon, van Biesebroeck, and Gereffi Citation2008). Corporate groups are likely to apply a larger number of company standards than single firms because they govern a higher number of internal interfaces. They are expected to benefit from internal standardisation through lower intra-firm transaction costs, higher quality, and optimised R&D and innovation activities in all their affiliates.

3. Empirical analysis

3.1. Data and variable description

The empirical analysis is based on data from the German Standardization Panel (GSP) collected in 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016. The GSP is a project initially supported by the German Society for the Promotion of Research on Standardization (FNS e.V.). The possibility to contact German firms active in formal standard-setting organisations to participate in the survey was only facilitated by the collaboration between the German Institute for Standardization (DIN e.V.) and the Technical University of Berlin. For this reason, the research is limited to representatives of companies based in Germany.

The final sample consists of 725 firms for which all relevant variables can be observed. Due to panel attrition and item non-response, panel data structure cannot be established to meet sample size requirements (50% of the sample only answered in one of the four years). The data set pools cross-sectional information, i.e. for each firm observations from only one year enter the analysis. Included are 89 questionnaires from 2014, 145 from 2015, 57 from 2015 and 434 from 2016.

The dependent variable is the number of company standards utilised internally by the firms. It is divided into four categories: no company standards (n = 121), between 1 and 10 (n = 252), between 11 and 100 (n = 237), or more than 100 (n = 115) company standards. The relationship under investigation is whether companies part of corporate groups are more likely to apply a larger number of company standards than firms that do not belong to a company network. The independent (binary) variable of interest indicates firms part of a corporate group whose headquarters and subsidiaries are located in Germany (11% of the entire sample) and MNEs with headquarters either in or outside of Germany (55%). The control group are single firms unattached to a corporate group, which represent 34% of the sample. Simple descriptive statistics reported in Table show that the majority of firms in the sample uses between 1 and 100 company standards. The share of non-users is highest among single firms and lowest among multinational groups. While only 6% of the single firms implement more than 100 company standards, this applies to more than 20% of all corporate groups.

Table 1. Application of company standards by form of business organization.

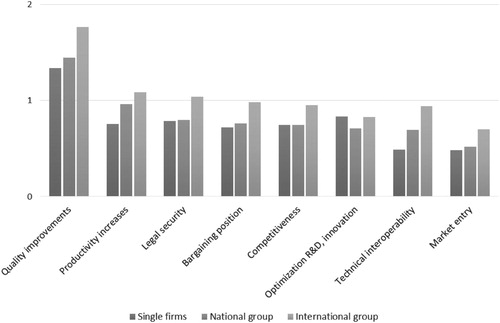

The participants of the German Standardization Panel were asked to rate the impact of company standards on eight factors of business success on a scale from −3 (very negative) to +3 (very positive). Figure reports the average values for single firms and corporate groups, respectively. The impact on ‘quality improvements’ is on average considered the most important, followed by ‘productivity increases (including cost reductions)’ and ‘legal security’. Firms that belong to a corporate group perceive the application of company standards as more beneficial to almost all the success factors than single firms. According to simple t-test statistics, only the effect on the ‘optimization of R&D and innovation activities’ is rated equally high by all respondents. Due to small sample size, the following analyses use binary variables to measure the motives for the application of company standards. The variables equal 1 if the impact of company standards on the respective factor is positive (value 2) or very positive (value 3), and zero otherwise (values −3–1).

Figure 2. Average impact of company standards on business success factors by form of business organization; measured on a scale from −3 (very unimportant) to +3 (very important).

From the theoretical elaboration we concluded that the number of applied standards, the form of business organisation, and the impact of company standards on success factors are all positively correlated with size, innovation activities, and extent of internal and external standardisation work of the firm. For example, large firms have more resources to develop standards (Blind Citation2004) and their value-chains are more likely to be fragmented.

Internal standardisation work is captured by a binary variable that takes the value one if the company has its own standardisation department and zero otherwise. External standardisation activities are measured by firms’ engagement in international standardisation organisations, such as ISO and IEC. Due to the general set up of the survey, almost 90% of the firms in the sample participate in formal standardisation processes at national level. This measure then should also reflect whether the firm is focused on the domestic market only, or whether it sells products on the European and international market as well.

Binary variables indicate whether a firm undertook product or process innovation in the previous year. Industry and year dummies control for sector- and year-specific effects.

Mean values of the independent variables for single firms and corporate groups are reported in Table . Simple t-test statistics show that corporate groups are larger, more often engaged in internal and external standardisation work, more innovative and more often operate in mechanical and automotive engineering. The share of service providers is higher among single firms. Differences in mean values also exist between national and international corporate groups. MNEs employ a higher number of employees and more often have own standardisation departments. They are more likely to operate in the metal industry, but less likely to be service providers.

Table 2. Model statistics.

Pairwise correlations between potential confounding factors and the variables of interest provide no indication of multicollinearity problems.

3.2. Empirical model and results

The empirical analysis aims to determine the relationship between the number of company standards and the form of business organisation. Generalised ordered logit models take into account the ordinal scale of the dependent variable and allow to test the proportional odds assumption, i.e. whether the effect is the same for each category of the dependent variable (Williams Citation2006). If all explanatory variables meet the assumption, the proportional odds model is applied. The partial proportional odds model, in contrast, allows effects to differ between categories of the dependent variable.

The response variable is indicated by Y and has four ordered categories k (k = 1,.., K with K = 4). The probability of each category on a vector x of p covariates is given byFootnote1:

(1)

(1)

The ordinal logistic model considers one set of dichotomies for each cut-off of the response variable and compares the probability of an equal or smaller response () to the probability of a larger response (

). In case of the number of company standards, the first set compares no versus at least 1 company standard, the second set few versus some and the third set compares the application of a medium versus high amount of standards. As the probability that the response variable equals K or smaller values is always one, K−1 cumulative probabilities are considered. The equation for the proportional odds model is:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3) for

.

is the cut point

and

the vector of coefficients. It follows:

(4)

(4)

The probability for any given category j is then given by:

Parameters are estimated using maximum likelihood estimation.

The model results are depicted in Table . In the first specification (SI), reported in column I, the main independent variable of interest is the binary variable that indicates whether a firm is part of a corporate group or not. In column II, an interaction term indicating if firm introduced both product and process innovation is included. Both specifications fulfil the parallel lines assumption. Specification SIII and SIV report coefficients for the variables measuring the motives for standardisation. Model statistics in Table indicate an overall good fit of the models. As apparent from Table A1 in the Appendix, that reports the estimation results for increasingly restrictive assumptions for outliers determined by plotting deviance residuals against the estimated logistic probability (Sarkar, Midi, and Rana Citation2011), the results are robust towards the exclusion of outliers.

Table 3. Mean values of independent variables by form of business organization.

Table 4. Proportional and partial proportional odds models.

3.2.1. Factors related to the number of applied company standards

The estimation results confirm that the membership with a corporate group is positively related to the application of company standards. Highly significant correlations exist between standards’ usage and number of employees, the existence of standardisation departments and the introduction of process innovations. Including a dummy for whether companies undertake both product and process innovations as a measure for more innovative firms does not affect the results (see column II). Results indicate that process innovations alone increase the likelihood to apply company standards. Likewise, Terziovski and Guerrero (Citation2014) establish a positive link between companies’ implementation of the international quality management standard ISO 9000 and process but not product innovation. In contrast, the analysis by Camisón and Puig-Denia (Citation2016) suggests that the implementation of quality management is not directly related to process innovation performance. In terms of year effects the results suggest that companies answering in 2013 and 2014 tend to be more likely than firms in 2016 to apply company standards.

A more detailed analysis is reported in Table and reveals that only for MNEs the effect is the same for each category. National corporate groups that have no subsidiaries abroad are more likely than single firms to apply more than 100 company standards (Cut 3), but with respect to lower amounts (Cut 1 and 2) no differences between the two groups can be observed. This implies that some national groups are more similar to single firms with respect to the application of company standards than others.

Table 5. Partial proportional odds model (SV) differentiating between national and international corporate groups.

Column SIII of Table reports the estimated coefficients for the relations between the motives for internal standardisation and the number of applied company standards. The results imply that firms that expect company standards to have a positive impact on quality, productivity, legal security, and technical interoperability apply more company standards than firms for which they are less beneficial. However, quality improvement is not confirmed to be a significant driver for the application of more than 100 company standards. The variables measuring the importance of standards for market entry, optimisation of R&D and innovation activities, competitiveness, and bargaining position towards suppliers and customers are not significantly related to more extensive implementation of company standards.

3.2.2. Factors related to the motives to apply company standards

The literature review showed that the special role of company standards in corporate groups is driven by their positive impact on intra-firm transaction costs, quality management, and the governance of internal interfaces through the realisation of product portfolio compatibility and transfer of company-specific know-how. The fact that the inclusion of the corporate group dummy does not alter the results (see column SIV in Table ) is a first indication that there are only minor differences in the motives depending on the form of business organisation.

In order to empirically test for differences in motives between corporate groups and single firms, eight regressions analyse the relationship between binary variables measuring a positive assessment of the impact of company standards on factors of business and form of business organisation, firm size, external standardisation and innovation activities, industry, and year dummies. Multivariate probit models are applied to control for unobserved factors that influence the impact assessments regarding the success factors simultaneously (Greene Citation2012). The results for corporate groups are reported in Table , differences between national groups and MNEs in Table A2 in the Appendix.

Table 6. Multivariate probit regressions for the motives to apply company standards.

Firms that are part of a corporate group more often state that company standards have a positive impact on market access and interoperability than single firms. The findings support that the importance of internal standardisation for the conformance of products and processes with local entry requirements is greater for multinational corporations that operate all over the world. With respect to the realisation of technical interoperability, the coefficient is significantly positive for both national and multinational groups. The results point towards a special role of company standards in the development and management of internal platforms. However, the significant differences in the mean values between national and international corporate groups with respect to ‘quality improvements’ suggested by descriptive statistics cannot be confirmed. Factors related to a higher assessment of the impact of company standards on quality are size, existence of standardisation department and process innovations.

Whereas the existence of a standardisation department is a highly significant predictor for a positive assessment of the impact of company standards, the participation in international standardisation processes is not related to any of the different motives to apply company standards. Company standards can possibly be more successfully applied when the responsibilities for their development lie within a specialised department. However, the direction of the causal relationship is not clear, i.e. whether the results imply that the perception of the effects of company standards is higher because of the existence of such a department or vice versa.

The empirical analysis further confirms that large firms are more likely than smaller firms to apply company standards for improvements in quality, legal security, competitiveness, and interoperability. In contrast, company internal standards facilitate productivity increases, cost reductions and improvements in bargaining position towards both suppliers and customers.

Interesting differences also exist with respect to the type of innovation. Firms that introduced product innovations in the previous years are more likely to successfully apply company standards for the optimisation of R&D and innovation activities. The result supports the arguments of other scholars about the effect of standardisation on innovation processes. Christensen, Suarez, and Utterback (Citation1998), for example, highlight that modularity fosters product component innovation that facilitates adaption to consumer needs and increases differentiation (Langlois and Robertson Citation1992). Process innovations are related to a more positive assessment of the impact of company standards on all factors relevant for business success except bargaining position and competitive advantages.

Assuming that the direction of the effect is from innovation to impact on success factors, the findings imply that innovative processes facilitate the application of company standards to ensure quality, legal conformity, interoperability, and fulfilment of market entry conditions through specification of relevant requirements. In addition, only firms with optimised processes can gain from internal standardisation in terms of optimised R&D activities, efficiency gains, and cost reductions through economies of scale. The results also indicate a positive impact of the application of company standards on process innovation complementing the similar findings regarding the international quality management standard ISO 9001 by Terziovski and Guerrero (Citation2014) or Perdomo-Ortiz, González-Benito, and Galende (Citation2009). However, the present analysis does not allow to draw conclusions on the direction of causality.

3.2.3. Limitations of the empirical analysis

The major limitation of the empirical analysis is the selection bias towards German firms participating in national standardisation organisations. The internal validity of the results could be affected by the influence of unobserved factors and errors of measurement. For example, the variable capturing innovativeness may not be a perfect proxy for the R&D activities of the firms. In addition, no statements can be made about the direction of causality based on cross-sectional analysis. Unfortunately, the data from the GSP does not yet allow for robust panel data analysis, due to small sample size.

The results indicate but provide no direct evidence that there is a positive relationship between foreign direct investment and the application of company standards. The preferred group to compare with MNEs would be corporate groups without subsidiaries abroad instead of single companies, because they are more similar to MNEs with respect to their organisational structure. However, estimation results of differences between MNEs and national corporate groups would be questionable due to the small sample size.

4. Conclusion

In the course of global integration, international firms face despite trends towards harmonisation (Ghadge et al. Citation2019) strong pressures to adapt their products to local consumer needs and to achieve cost efficiency in order to compete with global competitors. The reduction of communication and transaction cost facilitates the further differentiation of the value-chains and opens up opportunities to develop complex international strategies. By codifying information, specifying requirements and increasing interoperability, standards play a crucial role in the success of such operations. Corporate groups,particularly benefit from the application of company standards. If value-chain activities become more complex and include company-specific know-how and resources, company standards can act as a tool for coordinating internal interfaces and integrating subsidiaries worldwide. They transfer information and knowledge, thereby keeping high-value assets within the boundaries of the firm and facilitating the exploitation of competitive advantages abroad. Internal standardisation supports the development of a strong corporate culture and allows a more effective monitoring of subsidiary performance. Better quality assurance increases customer satisfaction and loyalty, and thereby improves the global image of the firm. Standardisation of product specifications facilitates modularisation and the development of product platforms, which increases flexibility, while efficiency gains can still be achieved.

Using data from the GSP, this paper empirically tests the relationship between the application of company standards and the form of business organisation. Although the survey is focused on companies active in the German standardisation body DIN, more than half of the answers are from international groups, which allows to generalise at least for this specific type of companies, which is in the focus of the analysis, for companies in Europe or even the Western world. Controlling for size, standardisation and innovation activities as well as industry, the results confirm that corporate groups utilise a higher number of company standards than single companies in Germany. Additional factors are firm size, the existence of a standardisation department, and process innovation.

The main motives for internal standardisation are quality improvements, increase in productivity, legal security and technical interoperability. Significant differences between corporate groups and single firms only exist regarding the assessment of the impact of company standards on the realisation of technical interoperability and the fulfilment of market entry conditions. While only international corporate groups have a higher likelihood to give a positive assessment regarding market access, both national and international groups that company standards enhance interoperability. The results underline the special role of internal standardisation for the development and management of internal platforms and the conformity of products and processes with local entry requirements when operating in different business environments. In addition, large firms are more likely than smaller firms to apply company standards for quality improvements, legal security, technical interoperability, and competitiveness. No differences exist with respect to improvements in productivity and bargaining position depending on firm size. Accordingly, small and especially medium-sized firms should consider internal standardisation as a strategic tool for the optimisation of their internal processes. The level of innovativeness is a relevant factor for the impact of company standards on all success factors except bargaining position and competitiveness.

So far our analysis has been focused on existing companies and corporate groups. However, mergers and acquisitions should consider not only the compatibility or complementarity of technology and product portfolios, but also company standards as an important element of companies’ technological infrastructure. These have to be merged or integrated in order to achieve quality improvements, increases in productivity and eventually, a higher level of competitiveness. So far the mergers and acquisition literature has not taken the relevance of company standards into account. Our empirical analysis confirms their relevance in particular for corporate groups, whose composition is in general the result of mergers and acquisition of firms.

The trend from value chains to value networks (Ricciotti Citation2019) between companies, but also within corporate groups, will even further increase the need for company standards in general and interoperability standards in particular, because the number of possible interfaces within corporate groups and between companies is going to increase exponentially. In addition, the increasing digitalisation of the industry will generate cyber-physical systems combining physical and software components, which require standards to coordinate the physical with the software system (Hwang et al. Citation2017), e.g. in smart manufacturing (Kusiak Citation2018). Moreover, distributed technologies, such as blockchains, generates the need for standards, in particular, for interoperability standards; but also additive manufacturing the requirement for measurement standards (Mani et al. Citation2017).

The implications of this research is of considerable importance to managers of companies’ value chains, who should consider the effects of company standards on the governance of inter- and intra-firm relationships. In addition, the application of high-quality company standards creates positive externalities to the whole economy, which provides a rationale for government support for internal standardisation. The research results suggest that the support should be targeted in particular to small and medium-sized enterprises that value company standards as beneficial for productivity increases and cost reductions as large firms. However, the latter are still more likely to successfully apply company standards for improvements in quality, competitiveness, and interoperability.

More research is needed on the role of company standards for the diffusion of information, cultural norms, and values in corporate groups. Both innovation and standardisation researchers should focus their attention on the positive relationship between process innovation and application of company standards and delve deeper into the mechanisms of knowledge and technology transfer in order to assess the potentials of standardisation for innovation activities and success.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the funding of the German Standardization Panel by the German standardisation institute DIN, which made this analysis possible. Furthermore, Knut Blind has been received for the revisions of the paper funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 770420 – EURITO.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

ORCID

Knut Blind http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6510-122X

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Explanations for the formal model are based on Hosmer, Lemeshow, and Sturdivant (Citation2013) and Fullerton (Citation2009).

2 Includes mining and quarrying, energy and water supplies, and construction.

References

- Argyres, N., and L. Bigelow. 2010. “Innovation, Modularity, and Vertical Deintegration: Evidence From the Early U.S. Auto Industry.” Organization Science 21 (4): 842–853. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1090.0493

- Baake, P., and V. Schlippenbach. 2011. “Quality Distortions in Vertical Relations.” Journal of Economics 103 (2): 149–169. doi: 10.1007/s00712-011-0194-z

- Bartlett, C. A., and S. Ghoshal. 2002. Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Blind, K. 2004. The Economics of Standards. Theory, Evidence, Policy. Cheltenham, UK, Northhampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

- Blind, K. 2006. “Explanatory Factors for Participation in Formal Standardisation Processes: Empirical Evidence at Firm Level.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 15 (2): 157–170. doi: 10.1080/10438590500143970

- Blind, K. 2016. “The Impact of Standardisation and Standards on Innovation.” In Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact, edited by Edler, et al, 423–449. Cheltenham, UK, Northhampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

- Blind, K., and A. Mangelsdorf. 2016. “Motives to Standardize: Empirical Evidence From Germany.” Technovation 48-49: 13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2016.01.001

- Blind, K., A. Mangelsdorf, C. Niebel, and F. Ramel. 2018. “Standards in the Global Value Chains of the European Single Market.” Review of International Political Economy 25 (1): 28–48. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2017.1402804

- Blos, M. F., S. L. Hoeflich, E. M. Dias, and H. M. Wee. 2016. “A Note on Supply Chain Risk Classification: Discussion and Proposal.” International Journal of Production Research 54 (5): 1568–1569. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2015.1067375

- Boiral, O. 2003. “ISO 9000: Outside the Iron Cage.” Organization Science 14 (6): 720–737. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.6.720.24873

- Boiral, O. 2007. “Greening Through ISO 14001: A Rational Myth?” Organization Science 18 (1): 127–146. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0224

- Calantone, R. J., S. Tamer Cavusgil, J. B. Schmidt, and G.-C. Shin. 2004. “Internationalization and the Dynamics of Product Adaptation - An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 21: 185–198. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-6782.2004.00069.x

- Camisón, C., and A. Puig-Denia. 2016. “Are Quality Management Practices Enough to Improve Process Innovation?” International Journal of Production Research 54 (10): 2875–2894. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2015.1113326

- Christensen, C., A. Suarez, and J. Utterback. 1998. “Strategies for Survival in Fast-Changing Industries.” Management Science 44: 207–220. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.44.12.S207

- Christmann, P. 2004. “Multinational Companies and the Natural Environment: Determinants of Global Environmental Policy Standardization.” Academy of Management Journal 47 (5): 747–760.

- Clougherty, J. A., and M. Grajek. 2008. “The Impact of ISO 9000 Diffusion on Trade and FDI: A New Institutional Analysis.” Journal of International Business Studies 39 (4): 613–633. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400368

- Clougherty, J. A., and M. Grajek. 2014. “International Standards and International Trade: Empirical Evidence From ISO 9000 Diffusion.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 36: 70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijindorg.2013.07.005

- Coase, R. H. 1937. “The Nature of the Firm.” Economica 4 (16): 386–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x

- De Casanove, A., and I. Lambert. 2016. “How Corporate Standardisation Shapes Tomorrow’s Business.” In Effective Standardization Management in Corporate Settings, edited by K. Jakobs, 1–17. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- De Vries, H., F. Slob, and Z. van Gansewinkel. 2006. “Best Practice in Company Standardization.” International Journal of IT Standards and Standardization Research 4: 62–85. doi: 10.4018/jitsr.2006010104

- Dowell, G., S. Hart, and B. Yeung. 2000. “Do Corporate Global Environmental Standards Create or Destroy Market Value?” Management Science 46 (8): 1059–1074. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.46.8.1059.12030

- Dunning, J. H. 1993. Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy. Harlow, UK: Addison-Wesley.

- Festing, M., and J. Eidems. 2011. “A Process Perspective on Transnational HRM Systems - A Dynamic Capability-Based Analysis.” Human Resource Management Review 21 (3): 162–173. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.02.002

- Fortanier, F., A. Kolk, and J. Pinkse. 2011. “Harmonization in CSR Reporting.” Management International Review 51: 665–696. doi: 10.1007/s11575-011-0089-9

- Fullerton, A. S. 2009. “A Conceptual Framework for Ordered Logistic Regression Models.” Sociological Methods & Research 38 (2): 306–347. doi: 10.1177/0049124109346162

- Gawer, A., and M. A. Cusumano. 2013. “Industry Platforms and Ecosystem Innovation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 31 (3): 417–433. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12105

- Gereffi, G., J. Humphrey, and T. Sturgeon. 2005. “The Governance of Global Value-Chains.” Review of International Political Economy 12 (1): 78–104. doi: 10.1080/09692290500049805

- Gereffi, G., and J. Lee. 2012. “Why the World Suddenly Cares About Global Supply Chains.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 48 (3): 24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-493X.2012.03271.x

- Ghadge, A., E. Kidd, A. Bhattacharjee, and M. K. Tiwari. 2019. “Sustainable Procurement Performance of Large Enterprises Across Supply Chain Tiers and Geographic Regions.” International Journal of Production Research 57 (3): 764–778. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2018.1482431

- Gibbon, P., and S. Ponte. 2005. Trading Down: Africa, Value-Chains and the Global Economy. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Temple University Press.

- Greene, W. H. 2012. Econometric Analysis. 7th ed. Boston, MA, USA: Prentice Hall.

- Großmann, A.-M. C. 2015. The Microeconomics of Standards. Five Essays on the Relation of Standards to Innovation and Inter-firm Relationships. Dissertation. Berlin, Germamy: Technische Universität Berlin.

- Großmann, A.-M. C., and P.-V. von Gruben. 2014. “The Role of Company Standards in Supply Chains – The Case of The German Automotive Industry.” In Innovative Methods in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Current Issues and Emerging Practices, edited by T. Blecker, 99–121. Berlin, Germany: epubli GmbH.

- Großmann, A.-M. C., P.-V. von Gruben, and L. K. Lazina. 2016. “Strategic Development and Implementation of Company Standards.” In Effective Standardization Management in Corporate Settings, edited by K. Jakobs, 77–104. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global.

- Guler, I., M. F. Guillén, and J. M. Macpherson. 2002. “Global Competition, Institutions, and the Diffusion of Organizational Practices: The International Spread of ISO 9000 Quality Certificates.” Administrative Science Quarterly 47 (2): 207–232. doi: 10.2307/3094804

- Hansen, M. T., and B. Lovas. 2004. “How Do Multinational Companies Leverage Technological Competencies? Moving From Single to Interdependent Explanations.” Journal of Management Studies 25: 801–822.

- Harzing, A.-W., and A. Sorge. 2003. “The Relative Impact of Country of Origin and Universal Contingencies on Internationalization Strategies and Corporate Control in Multinational Enterprises: Worldwide and European Perspectives.” Organization Studies 24 (2): 187–214. doi: 10.1177/0170840603024002343

- Henson, S., and T. Reardon. 2005. “Private Agri-Food Standards: Implications for Food Policy and the Agri-Food System.” Food Policy 30: 241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.05.002

- Hosmer, D. W., S. Lemeshow, and R. X. Sturdivant. 2013. Applied Logistic Regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hudson, J., and P. Jones. 2003. “International Trade in ‘Quality Goods’: Signalling Problems for Developing Countries.” Journal of International Development 15 (8): 999–1013. doi: 10.1002/jid.1029

- Huo, B. F., Z. J. Han, and D. Prajogo. 2014. “The Effect of ISO 9000 Implementation on Flow Management.” International Journal of Production Research 52 (21): 6467–6481. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2014.895063

- Hwang, G., J. Lee, J. Park, and T. W. Chang. 2017. “Developing Performance Measurement System for Internet of Things and Smart Factory Environment.” International Journal of Production Research 55 (9): 2590–2602. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2016.1245883

- Jaffee, S., and O. Masakure. 2005. “Strategic Use of Private Standards to Enhance International Competitiveness: Vegetable Exports From Kenya and Elsewhere.” Food Policy 30 (3): 316–333. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.05.009

- Kaplinsky, R. 2010. “The Role of Standards in Global Value-chains.” Policy Research Working Papers, No. 5396, World Bank, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Kogut, B., and U. Zander. 1993. “Knowledge of the Firm and the Evolutionary Theory of the Multinational Corporation.” Journal of International Business Studies 24 (4): 625–646. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490248

- Krugman, P. 1995. “Growing World Trade: Causes and Consequences.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 25 (1): 327–362. doi: 10.2307/2534577

- Kusiak, A. 2018. “Smart Manufacturing.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (1-2): 508–517. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2017.1351644

- Langlois, R., and P. Robertson. 1992. “Networks and Innovation in a Modular System: Lessons From the Microcomputer and Stereo Component Industries.” Research Policy 21: 297–313. doi: 10.1016/0048-7333(92)90030-8

- Larsson, R., and S. Finkelstein. 1999. “Integrating Strategic, Organizational, and Human Resource Perspectives on Mergers and Acquisitions: A Case Study of Synergy Realization.” Organization Science 10 (1): 1–26. doi: 10.1287/orsc.10.1.1

- Lerner, J., and J. Tirole. 2014. “A Better Route to Tech Standards.” Science 343 (6174): 972–973. doi: 10.1126/science.1246439

- Liker, J. K., P. D. Collins, and K. M. Hull. 1999. “Flexibility and Standardization: Test of a Contingency Model of Product Design–Manufacturing Integration.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 16: 248–267. doi: 10.1111/1540-5885.1630248

- Lorenz, A., M. Raven, and K. Blind. 2019. “The Role of Standardization at the Link Between Product and Process Development in Biotechnology.” Journal of Technology Transfer 44: 1097–1133. doi: 10.1007/s10961-017-9644-2

- Mani, M., B. M. Lane, M. A. Donmez, S. C. Feng, and S. P. Moylan. 2017. “A Review on Measurement Science Needs for Real-Time Control of Additive Manufacturing Metal Powder bed Fusion Processes.” International Journal of Production Research 55 (5): 1400–1418. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2016.1223378

- Marucheck, A., N. Greis, C. Mena, and L. Cai. 2011. “Product Safety and Security in the Global Supply Chain: Issues, Challenges and Research Opportunities.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (7-8): 707–720. doi: 10.1016/j.jom.2011.06.007

- Mellahi, K., J. G. Frynas, and D. G. Collings. 2015. “Performance Management Practices Within Emerging Market Multinational Enterprises: The Case of Brazilian Multinationals.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27 (8): 1–30.

- Mikkola, J. 2006. “Capturing the Degree of Modularity Embedded in Product Architectures.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 23: 128–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2006.00188.x

- Muffatto, M. 1999. “Introducing a Platform Strategy in Product Development.” International Journal of Production Economics 60: 145–153. doi: 10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00173-X

- Ozbugday, F. C. 2019. “The Effects of Certification on Total Factor Productivity: A Propensity Score Matching Approach.” Managerial and Decision Economics 40 (1): 51–63. doi: 10.1002/mde.2979

- Perdomo-Ortiz, J., J. González-Benito, and J. Galende. 2009. “The Intervening Effect of Business Innovation Capability on the Relationship Between Total Quality Management and Technological Innovation.” International Journal of Production Research 47 (18): 5087–5107. doi: 10.1080/00207540802070934

- Perera, C. 2007. “Standardization in Product Development and Design.” In Standardisation in Companies and Markets, edited by W. Hesser, 171–212. Hamburg, Germany: Helmut-Schmidt-University.

- Perez-Aleman, P. 2011. “Collective Learning in Global Diffusion: Spreading Quality Standards in a Developing Country Cluster.” Organization Science 22 (1): 173–189. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1090.0514

- Prahalad, C. K., and Y. Doz. 1987. The Multinational Mission: Balancing Local Demands and Global Vision. New York, USA: Free Press.

- Prakash, A., and M. Potoski. 2007. “Investing Up: FDI and the Cross-Country Diffusion of ISO 14001 Management Systems.” International Studies Quarterly 51: 723–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00471.x

- Ricciotti, F. 2019. “From Value Chain to Value Network: A Systematic Literature Review.” Management Review Quarterly, 1–22.

- Sarkar, S. K., H. Midi, and S. Rana. 2011. “Detection of Outliers and Influential Observations in Binary Logistic Regression: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Applied Sciences 11: 26–35. doi: 10.3923/jas.2011.26.35

- Schilling, M. 2000. “Toward a General Modular Systems Theory and its Application to Interfirm Product Modularity.” The Academy of Management Review 25: 312–334. doi: 10.5465/amr.2000.3312918

- Simpson, T. W. 2004. “Product Platform Design and Customization: Status and Promise.” Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing 18 (1): 3–20. doi: 10.1017/S0890060404040028

- Sturgeon, T., J. van Biesebroeck, and G. Gereffi. 2008. “Value-chains, Networks and Clusters: Reframing the Global Automotive Industry.” Journal of Economic Geography 8: 297–321. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbn007

- Subramaniam, M. 2006. “Integrating Cross-Border Knowledge for Transnational New Product Development.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 23: 541–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2006.00223.x

- Swann, G. M. P. 2010. International Standards and Trade: A Review of the Empirical Literature. OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 97, OECD Publishing, Paris, France.

- Tallman, S., and A. S. Chacar. 2011. “Knowledge Accumulation and Dissemination in MNEs: A Practice-Based Framework.” Journal of Management Studies 48: 278–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00971.x

- Terziovski, M., and J.-L. Guerrero. 2014. “ISO 9000 Quality System Certification and its Impact on Product and Process Innovation Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 158: 197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.08.011

- Ton, Z., and R. S. Huckman. 2008. “Managing the Impact of Employee Turnover on Performance: The Role of Process Conformance.” Organization Science 19 (1): 56–68. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1070.0294

- Van Beers, C., and F. Zand. 2014. “R&D Cooperation, Partner Diversity, and Innovation Performance: An Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 31 (2): 292–312. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12096

- Williams, R. 2006. “Generalized Ordered Logit/Partial Proportional Odds Models for Ordinal Dependent Variables.” The Stata Journal 6 (1): 58–82. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0600600104