Alain de Mijolla died on 24 January 2019. Born on 15 May 1933, he lived to be 85 years old. At his funeral, his family and friends paid him affectionate tribute and his grandchildren spoke fondly of their Papé, as grandfathers are known in Provence, and as he called his own grandfather who with his grandmother had brought him up.

Captain Rimbaud’s desertion (Citation1975b)

I will first give an example of the psychoanalyst Mijolla's work with his fine article of applied psychoanalysis about Arthur Rimbaud, which along with his other article on identification fantasies—Fantasmes d’identification: Jakob, Freud et Goethe (Citation1975a)—was awarded the Maurice Bouvet prize in 1976. Work on the identifications that will give a book: Visions of the Ego (Citation1981).

Modestly leaving to the numerous commentators on the poet's life and works the ambition of explaining the source of its creativity, Mijolla illustrates his theories concerning the importance and the forms of identifications by focusing specifically on what is missing from the works and the documents, namely the poet's father, Captain Frédéric Rimbaud.Footnote1 A young army volunteer, through his serious approach he became a non-commissioned officer then an officer promoted from the ranks. Sent to Algeria for eight years, after three years of combat he became head of the Arab office in Sebdou, a quieter post where his task was to administer matters relating to the native population and keep the army staff informed about their docility or any rumours circulating about the elusive Emir Abd-el Kader and his rebel troops. He returned to France in 1850 and married Vitalie Cuif in 1853 following his own father's death. Always posted far away from his family, he was never accompanied by them in his appointments, and he gave them a child on each of his return visits. He disappeared permanently from his family's life when Arthur was six years old, and this is the desertion to which Mijolla refers since Captain Rimbaud was never an army deserter, leaving only when he retired. Mijolla pertinently indicates that this time spent in his son's childhood and these procreations were enough to make impressions in a child's life. On condition of having the right. The article's title might have been the deprivation of this father by a mother who erased every trace of him from the family after he left. I will leave aside all the attention given by the author to the fearsome personality of this puritanical, merciless mother who was simultaneously exciting to her son. This is a woman who took her dead mother's place beside her father, moved near him to give birth, erased her brothers and sisters from the family heritage, broke with her first son who had been given her husband's forename, and finally created a place for herself between his father and Arthur in the family vault while inspecting his ancestors’ bones at a reduction in corpses, marvelling that Arthur's coffin was intact …

Mijolla suggests that initially, lacking a firm paternal identification, to separate from the incestual fusion with his mother, the poet carried out a furious counter-identification with her: debauched, licentious, scatological and sacrilegious, but with all her fanatical devotion! I had personally found a rather useful formulation for interpreting to patients who wanted at all costs to avoid resembling their parents the means by which they nevertheless perpetuated their images: “From a negative, the person can be easily recognised!”. I fear the disappearance of silver photography may soon remove any efficacy to my formulation …

Many quarrels erupted between Arthur's parents, of whom we have a curious account, according to an incident that Rimbaud is said to have related one day to his friend Delahaye:

Arthur Rimbaud was six years old. He could still remember what is likely to have been the last marital quarrel, in which a silver bowl placed on the sideboard played a role that left a permanent mark on his imagination. His father seized this bowl in fury, threw it on the floor from which it bounced back, making a musical sound, then put it back in its place, and his equally feisty mother took the resonant object in turn and made it perform the same dance, immediately picking it up and carefully putting it back where it was to stay. This was their way of emphasising their arguments and asserting their independence. Rimbaud remembered this thing because it had greatly amused him, and perhaps made him a bit envious because he himself would have so much liked to play at making the fine silver bowl run!. (Citation1923)

During one of his journeys, having deserted at Java from an engagement in the Dutch colonial army, motivated by an allowance, Rimbaud wrote a letter to the American consul in the form of a curriculum vitae, and here is an extract:

‘Bremen, the 14th May 77.

The undersigned Arthur Rimbaud — Born in Charleville (France) — Aged 23 — 5 ft. 6 height — Good healthy — Late a teacher of sciences and languages — Recently deserted from the 47e Régiment of the French Army (…) Would like to know on which conditions he could conclude an immediate engagement in the American navy (…). John Arthur Rimbaud.

It is unknown whether he sent only the letter—and introducing himself as a deserter was not the best argument—but what is striking is that it is his father who belonged to the 47th regiment of the French army: identification.

And there is another clue: in August 1880, Alfred Bardey records in his private journal:

M. Dubarme talks about a young man he employs in the shops where the coffee is sorted (…) by the name of Arthur Rimbaud. He is a nice, tall boy who talks little and his short explanations are accompanied by small sharp gestures of the right hand that are out of sequence. He is 25 years old, born in Dole (Jura) and he comes from the island of Cyprus where he was head of a team of quarrymen.

Having failed to win fame with Une saison en Enfer and then broken with Verlaine, who shot at him in Brussels and was later imprisoned, Rimbaud abandoned his poetry, describing it as “scraps”, and instead of the escapes that always brought him back to his mother, he then made a random attempt at a career that resembled his father's, and in his last piece of writing gave a precise and detailed report on the colonial political situation of the kind his father had produced. He also envisaged, like him, getting married on returning home. However, the contrived nature of this unintegrated identification may have left him susceptible to a somatic disorganisation. He developed a cancer of the knee that brought him back to his mother and his sister. But in a delirium that preceded his death, he still feared that the army would seek him out as a deserter.

Mijolla concludes:

For Rimbaud, finding himself unable to mourn the deserter and take his place in an oedipal situation that is for ever blocked, his father's actual death then fulfils the need for an unconscious identification that ensures his temporary survival. Having, by this artificial means, become an adult other than himself, severed for all time from the dead child inside him with his irresoluble conflicts, Rimbaud appears to everyone suddenly metamorphosed. Here he is, serious, hard-working, concerned with creating a position for himself, keen for earnings. Mme Rimbaud can breathe again: he has truly changed, and he has been able to leave her. So she has not completely spoilt him!. (p. 450)

Mijolla quotes some apposite extracts from the poet's work, some of which bluntly demonstrate the hypomanic erotic fixation to the father's penis, and he also presents this portrait in “Mémoire” of the abandoned—or dead—mother, in Winnicott's sense or Green's?:

Madame stands too straight in the field/ nearby where the filaments from the work snow down; the parasol / in her fingers; stepping on the white flower; too proud for her children reading in the flowering grass / their book of red morocco! Alas, He, like / a thousand white angels separating on the road, / goes off beyond the mountain! She, all/ cold and dark, runs! after the departing man!Footnote2

In Mijolla's last interview (Citation2018), published in Psychanalyse et psychose, he explains his standpoint and their differences:

Alain de Mijolla: ‘My work on Freud enabled me to identify more closely what I was seeking. My major discovery was realising that a third element is always at work in transmissions. For me transmissions, whether intergenerational or intragenerational, are always made by the intermediary of a third, a third that is excluded, that is not seen, but is important. If the third is not sought, we can be misled. Between Freud and the grandfather, however, was his father who featured in Freud's combined identifications.

Nicolas Gougoulis then asks him: ‘The word “transgenerational” comes from a systemic thought, to which you bring the psychoanalytic concept of intergenerational transmission, emphasising the question of the third. Can you explain to me your emphasis on the differences?’

Alain de Mijolla: ‘Yes! The “trans” refers to a slightly magical transition through space from one moment to another that does not truly reflect the reality of a life: a chain of circumstances and people who lead to this transmission. That was why I rejected the work on the transgenerational by Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok (1978), which left a strong impression. We were good friends, but our disagreement on this question permanently strained our relationship. I did not agree with their conceptualisation of the relationship of unconscious to unconscious, which I felt belonged to a magical thinking. A purely unreal, purely fantasmatic world. Suddenly, there was no longer a third’ (Citation2018, 169).

Alain de Mijolla: Life and work

In analytic filiation from his analyst Conrad Stein, supervised by Denise Braunschweig, Mijolla became a member of the Paris Psychoanalytical Society (SPP) in 1968 and a training analyst in 1975. He resigned from the SPP in 2007. Having been brought up by his grandparents, he became interested in his history and, according to his wife Sophie de Mijolla Mellor, this was the starting point for his quest for the history of psychoanalysis. He assumed a completely original place in French psychoanalysis and in the SPP by instigating a research movement through his rare talent for harnessing energies and moving beyond institutional splits. This is testified by his Dictionnaire International de Psychanalyse (Citation2002), in which I was honoured to participate.

In 1982, Mijolla created with Jacques Caïn the Rencontres d’Aix-en-Provence, which brought analysts together in a friendly and unique setting until 1993. From the outset, research was done in the context of enjoyable meetings. Then in 1985 he launched the venture of the Association internationale d’histoire de la psychanalyse (AIHP), which he chaired until 2011 in a spirit of open inquiry that no longer concerned France alone but the history of Freud's discoveries. These meetings were held every other year in various European cities, then a journal emerged in 1985, published by PUF, the Revue internationale d’histoire de la psychanalyse. This ceased publication after six issues because of a lack of commercial success. Mijolla then also became editor of the Belles Lettres ‘Confluents psychanalytiques’ collection, and PUF's “Histoire de la psychanalyse” collection.

The international dimension of Mijolla's individual work was recognised in 2004 by the Sigourney Award, which had already been granted to the AIHP in 2001.

For the SPP, he simultaneously carried out a role of opening up debate, overcoming splits that had emerged from the schisms that characterised French psychoanalysis since 1953, and recalibrated the memory of French psychoanalysis, often trapped in loyalty to their Lacanian filiation from some authors, such as to the works of Elizabeth Roudinesco, the daughter of Jenny Aubry, who was a member of the École freudienne founded by Jacques Lacan.

Accordingly Mijolla's contributions can be found on the SPP website for the history of psychoanalysis in France: https://www.spp.asso.fr/textes/histoire-de-la-psychanalyse-en-france. The passages on the Second World War, the suspension of psychoanalytic activities and organisations are essential reading. In fact in that period the archives disappeared. The Rfp's second issue of 1939 went undistributed—“the publisher and printer having been mobilised”, as was recorded in issue 1 of 1948, which republished its table of contents (including an article by René Allendy on “Le chahut à l’école [Rowdiness in schools]”.)

Mijolla emphasises that no organisation sought any compromise with the occupier, unlike in Germany. However, René Laforgue's role is more ambiguous. Suspected of collaboration, he was acquitted following testimonies of assistance he gave to Jews during the war, when he took part in a trip to Germany organised in 1941 by Hitler's favourite sculptor, Arno Breker. It was later discovered that he had contacted Mathias Gœring in connection with a plan to create a French branch of Nazi psychotherapy …

The loyalty of Laforgue's analysands—André Berge, Françoise Dolto, Juliette Favez-Boutonier, Georges Mauco and Blanche Reverchon-Jouve—then played a role first in the founding of the Centre d’étude des Sciences de l’homme with its publication Psyche in 1946, which Mijolla emphasises was later surprisingly unknown, a highly eclectic group close to Catholic circles, and then later in the choices made during subsequent schisms.

With the pre-war archives having disappeared, the Revue française de psychanalyse is a shared legacy for the whole of French psychoanalysis up to 1953.Footnote3

A book-lover, Mijolla chose to leave his personal library to the SPP's Sigmund Freud Library.

Following the path indicated by Mijolla encourages us to question the past. In a short film I made with Ambre Benkimoun about the earliest French psychoanalysts,Footnote4 her commentary emphasises the difficulty of implanting psychoanalysis in a France that was half anti-Semitic and almost entirely anti-German immediately after the First World War. Some psychiatrists proclaimed the need to create a “French-style psychoanalysis”. But it was psychoanalysts who had immigrated from Eastern Europe who conducted the earliest analyses, such as Eugénie Sokolnicka, of Polish origin, analysed by Freud then Ferenczi, who settled in Paris in 1921. She was welcomed into Prof. Henri Claude's department at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne. Not being a doctor, however, she was replaced by René Laforgue (already!) who had previously been her patient for several months.

It was not to Sokolnicka that Freud turned for support to promote the creation of the SPP in 1926 but Marie Bonaparte, in whom he had complete confidence—rightly so as she would later succeed in saving him from the Nazis—and with indisputable political sense: a Princess Bonaparte of Greece was much more reassuring for the French …

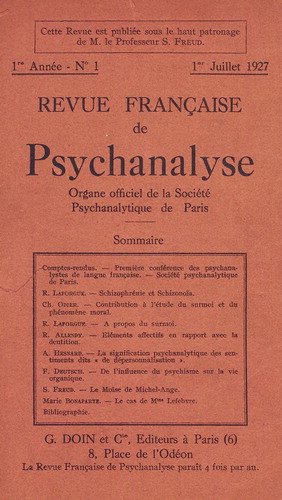

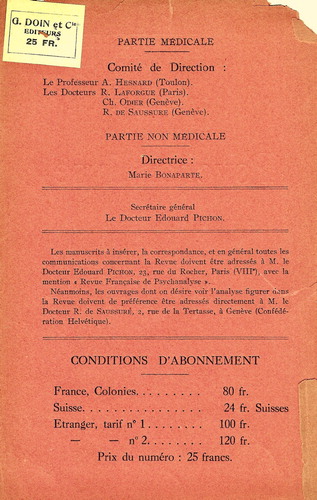

The question of analysis conducted by non-medics was therefore present from the outset even before the SPP was established in November 1926, at which, with the creation on the same day of the Revue française de psychanalyse, Freud's patronage confirmed his acceptance of “lay analysis” through the position that Marie Bonaparte held in these two operations. Accordingly, she appears as the author in the table of contents of the Rfp's first issue in July 1927, where doctors and non-medics are not distinguished, but where the inside cover also clearly explains that she is the editor only of the “non-medical part” of the issue, the “medical part” being entrusted to Prof. Hesnard, and the medics, Doctors Laforgue, Odier and de Saussure ( and ).

Figure 1. Cover and table of contents for the Rfp's first issue, with no distinction between articles according to whether the author is a doctor or not, or whether the subject is clinical or non-clinical.

Figure 2. Inside cover of the same issue, explaining the separate editing of the medical and non-medical parts.

In the 1930s the dangers were rising and Sokolnicka died, seemingly of suicide by gas, and Sophie Morgenstern—who had pioneered child analysis in France—having lost her daughter several months earlier, committed suicide when the Nazis re-entered Paris.

Following Mijolla's indicated path of elucidating events by their preceding history, it is striking to note the role of the 20th-century's two world wars in the emergence of psychoanalysis in France. Furthermore, however, it is possible to rediscover the meaning of the major schism that French psychoanalysis, unlike the English analysts, could not avoid. Although, retroactively, Lacan's personality structured (or de-structured …) psychoanalytic institutions in France, the origin of the schism was not connected with him, and it derived from a conflict around analytic trainingFootnote5 and power in the institutions.

Sacha Nacht wanted to reserve training firstly to doctors in the Institute of Psychoanalysis that he directed, whereas Daniel Lagache wanted to establish the teaching of psychoanalysis at university. He later succeeded in this and rejoined the IPA with the colleagues who broke away from Lacan and founded the Association psychanalytique de France. The protagonists initially had no other technical or theoretical disagreement.

The schism was in no sense directed at the IPA, of which Lacan had wished to remain a member, this having been refused him because of his transgressions concerning the length of sessions after the inquiry by the IPA committee on which Winnicott served. Among Lacan's paradoxes, it can be noted that he had co-authored with Sacha Nacht the “Doctrine” of the Institut de psychoanalyse, a text that, I believe, still governed the training when I undertook it, before systematically throwing into crisis the institution's role in training through his rebellions. Similarly, this proponent of a “return to Freud”—in fact more a useful discovery in France of the original Freudian texts—summoned up what were indisputably Catholic references in his theories, such as “The name of the Father”, and broke with the Freudian rootedness of the drive in the body to put forward a structuralist approach based on language, favouring synchrony over diachrony. Was this a return unknown to him of a “French-style psychoanalysis”?

Notes

1 The author explains:

A note in the 1963 edition of the Œuvres complètes (Citation1972) provides a brilliant example: “This father, absent from Rimbaud's correspondence as from his life, had permanently abandoned his wife and children following his retirement (at the age of 50). Captain Frédéric Rimbaud had then moved back to Dijon, the native town of his father, the tailor Didier Rimbaud. He died there at the age of 64, on 17 November 1878, and was buried the next day after a religious service at the church of Sainte-Bénigne”.

2 Five Poems by Rimbaud from Rimbaud: Complete Works, Selected Letters, a Bilingual Edition. Translated by Wallace Fowlie and revised by Seth Whidden. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

3 The digitisation by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France gives access to the Rfp's 20th-century issues on its Gallica site: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb34349182w/date.r=Psychanalyse.langEN and the article searches are facilitated by the Sigmund Freud Library website: http://bsf.spp.asso.fr/. Moreover, we are also working towards a forthcoming addition of the Rfp to the PEP archive.

5 Not unlike some recent conflicts within the IPA?

References

- Abraham, N., and M. Torok. 1994. The Shell and the Kernel. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Translated by Nicholas T. Rand [L’Écorce et le noyau. Paris: Flammarion, 1978].

- Delahaye, E. 1923. Rimbaud, l’artiste, l’être moral. Paris: Alb. Messein éditions, p. 17.

- Mijolla, A. de. 1975a. “Fantasmes d’identification: Jakob, Freud et Goethe [Identification Fantasies: Jakob, Freud and Goethe].” Études freudiennes 9-10: 167–210.

- Mijolla, A. de. 1975b. “La désertion du capitaine Rimbaud: enquête sur un fantasme d’identification inconscient d’Arthur Rimbaud [Captain Rimbaud’s Desertion: Inquiry into an Unconscious Identification Fantasy of Arthur Rimbaud].” Revue française de psychanalyse 39 (3): 427–458.

- Mijolla, A. de. 1981. Les visiteurs du Moi: fantasmes d’identification. [Visitors of the Ego: Identification Fantasies]. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, Confluents psychanalytiques.

- Mijolla, A., ed. 2002. Dictionnaire international de psychanalyse, editorial committee: Sophie de Mijolla Mellor, Roger Perron et Bernard Golse. Two volumes, Calmann-Lévy, 2002. [English edition: International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. Thomson Gale. 2005].

- Mijolla, A. de. 2018. “Une trajectoire intergénérationnelle [An Intergenerational Path].” Interviewed by Katryn Driffield and Nicolas Gougoulis. In Psychanalyse et psychose. 18 vols, 167–186. Centre de Psychanalyse & de Psychothérapie Evelyne et Jean Kestemberg.

- Moreau Ricaud, M. 2019. “Alain de Mijolla (1933-2019).” Le Coq-héron 236 (1): 11–14. Paris: Erès. doi: 10.3917/cohe.236.0011

- Rimbaud, A. 1972. Œuvres complètes. Edited and introduced by A. Adam, Paris: Pléiade ed. N.R.F., pp. 430–440.