ABSTRACT

National canons of history sparked intense debate among historians over the last years, history educators have regularly shown concerns regarding these canons. The main arguments are that history is instrumentalized for political purposes, and that canons are incompatible with multiculturality. In this study, the cases of the Netherlands and Belgium (Flanders) are used to discuss these concerns. The aim of this article is to gain a more complex understanding of the use of canonical discourse in the setting of history education. The current study actualizes and reconsiders Banks’ typologies of knowledge, and applies them to multicultural history education. Hence, the canon debates in the low countries are contextualized from an international perspective of debates on canon and history teaching. It is argued that both national canons specifically intend to confront popular knowledges and historical myths with academic historiographic discourses. More particularly both canons seek to include discourses on minority groups and multiculturality, which may benefit the use of transformative knowledge in history education. The use of canonical discourses however must not be reduced to transmission. Beside qualification history education also strives towards socialization and subjectivation. It is discussed how a thoughtful use of canonical discourse may add to realizing these purposes of education.

Introduction

National canons of history sparked intense debate among historians over the last years, both in the Netherlands and Flanders (Belgium). Stuurman used as a definition for a historical canon: ‘a master narrative of a community’s history, embodied in the social routines and professional mentalities of its recognized history specialists’ (Stuurman, Citation2006, p. 5). The Dutch Van Dale dictionary defines a canon as a ‘collection of facts, events, and works of art that are recognized in a culture as valuable and serve as points of reference in the study of that culture’. Cambridge dictionary speaks of ‘the writings or other works that are generally agreed to be good, important, and worth studying’. A historical canon is thus a guide: a narrative discourse that can provide a point of reference within a culture when studying the past. Originally, the term canon (‘canonization’) was used to denote the process of determining which religious writings would be included in the Bible. In the first ages of Christianity, a debate existed over which texts and scriptures would become part of this canon. The term was also used related with classical Greek literature: canonized literature was ascribed a certain intellectual authority. A literature canon, such as the canon of classical literature, assumes a certain authority of the texts included in it. If one esteems Homer and Cicero to be part of the canon of classical literature, this means that one regards them as part of a selection of must-read texts. The same goes for topics in history education that are regionally or nationally considered as essential. In large parts of Europe, it would be for many people unthinkable to delete the French Revolution from the history curriculum, and many American educators would find it unthinkable to erase the American Civil War from it. This indicates that these events belong to an implicit canon of history, and also that important context-dependent differences exist in this implicit historical canon. Moreover, the way these phenomena are used and described in history textbooks or in history classrooms is also often canonical: although some teachers may seek for authentic, personal or alternative narratives, master narratives dominate in history textbooks (Alridge, Citation2006; Grever & Van der Vlies, Citation2017). Hence, implicit canons are omnipresent in history education. Even if obligations to study these topics do not always exist in the official curriculum, still these less authoritative canons are subject to critique.

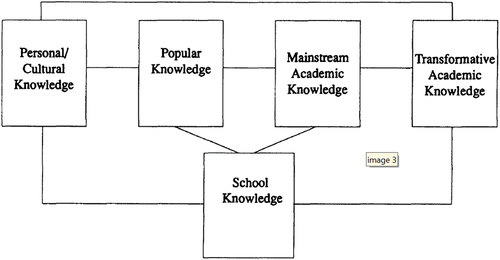

Banks’ typology of knowledge in multicultural education (Banks, Citation1993) provides a theoretical framework to understand and discuss the educational implications of canons, in particular in multicultural settings. He distinguishes five types of knowledge, all of which are needed in multicultural education to allow ‘students to become critical thinkers who have the knowledge, attitudes and skills to help the nation close the gap between its ideals and its realities’. (p. 5). Banks discerns personal and cultural knowledge from popular knowledge, mainstream academic knowledge, and mainstream transformative knowledge. His argument that students need understanding of the diverse epistemological underpinnings of all these sorts of knowledge in gaining increasing popularity among history education scholars (Mierwald & Junius, Citation2022). Personal and cultural knowledge are the concepts, explanations and interpretations that students derive from their homes, families and community cultures. This type of knowledge is described more recently as Funds of Knowledge, a theory that rests on the assumption that students are competent and have knowledge and skills, developed through their life experiences outside school (Hogg & Volman, Citation2020). Popular knowledge is a set of more or less implicit conceptions that are presented in the media as stories, anecdotes and events. Banks describes a series of tenets and myths on the popular American culture as examples, for instance the tenet that you can realize your dreams if you are willing to work hard enough. Popular knowledge is a crystallization of the master narratives that have been subject to critique of history educators for decades (Carretero & van Alphen, Citation2014). Deconstruction of popular knowledge is generally seen as a key task of history education (Carretero et al., Citation2012). Mainstream academic knowledge consists of the concepts, paradigms, theories, and explanations that constitute traditional and established knowledge in the behavioural and social sciences. This traditional knowledge is an expression of theories that mainstream scholars and researchers accept at a given moment. ‘Transformative academic knowledge consists of concepts, paradigms, themes, and explanations that challenge main-stream academic knowledge and that expand the historical and literary canon’ (Banks, Citation1993). Banks noted that the distinction between mainstream academic and transformative academic knowledge is not entirely stable. Four decades after Banks model was published the distinction between traditional and transformative academic knowledge seems even less clear. Banks (Citation1993) noted that scholarship since the 1970s was becoming institutionalized into mainstream academic knowledge, and also in school curricula. Banks’ examples are critical discourses that challenge Eurocentric perspectives on history, or that reassess the contribution of minority groups to historical phenomena. In a comparable recent argument Wills (Citation2001) argued that knowledge on actions and interactions between diverse groups should be used to give students’ insight in institutional racism, structural inequality, and power.

Finally, Banks defines school knowledge as the facts, concepts, and generalizations presented in textbooks, teachers’ guides, and the other forms of media designed for school use (Banks, Citation1993). It is consequently important to note that school knowledge is not simply an accessible version of mainstream academic knowledge. It has been repeatedly argued that history schoolbooks and other types of written and spoken discourse importantly affect what is learnt at school. School knowledge also consists of the teacher’s mediation and interpretation of that knowledge. Banks’ argument is that in multicultural education school knowledge should also address and reflect upon students’ funds of knowledge, and on transformative academic knowledge. Moreover, to enable students to become citizens that have developed the knowledge and skills that are needed to function a given society, it is also important to understand and deconstruct its popular myths (Barton, Citation2012) or to provide alternatives for it. depicts Banks’ types of knowledge graphically and shows that they are all interrelated.

Figure 1. Interrelations between types of knowledge in multicultural education (Banks, Citation1993).

The purpose of this article is to analyse the function of historical canons in multicultural education. I first describe the nature and content of two case studies of historical canons that were developed recently in the low countries and I use Banks’ typologies of knowledge to categorize both. Both examples explicitly aim to influence education, and the authors of both canons also reflect upon its use in a multicultural society. I then use these cases to explore the function of a canon for history education. I develop two arguments that attempt to reconcile the use of a canon with the requirements of education in multicultural settings: I address the socializing and subjectivizing functions of a historical canon and discuss the role of the teacher to target these functions.

Two historical canons of the Netherlands

In a period in which discussions on migration and multiculturality sparked political debate in the Netherlands, a right-wing government commissioned a group of academics and experts to articulate a canon of the Netherlands. The initiative was highly controversial from the start. It was seen an attempt to provide an answer to questions of identity that arose in the rapidly diversifying Dutch society (Grever, Citation2005). The historical canon of the Netherlands was described as a delineation of what everyone was supposed to know about the history of its country (Rijksoverheid, Citation2006). From its inception, it was clear that a historical canon in the Netherlands would have to remain changeable. and constantly subject to reflection (Bank & De Rooj, Citation2004). Positivist epistemological assumptions of the canon were avoided.

If the canon of the Netherlands should be an imperative about what everyone should know, then it must be seen as an attempt to promote academic historical discourse to becoming popular and cultural knowledge. The canon would then be used to construct a body of historical orientation knowledge. Wilschut argued for example for a frame of reference consisting of ‘a limited amount of easily remembered useful markers’ (Wilschut, Citation2002, p. 9). The argument that critical reflection on the past is possible only when a basic form of knowledge-accumulation has been realized, is in the past few years receiving also internationally increasing attention from teacher educators (Counsel, Citation2017; Fordham, Citation2016). There was however also immediate criticism of this canon-concept and on its content, especially from historians. Jonker for example, warned against ‘a forced inclusion of deviants’ (Jonker, Citation2006, p. 16). According to Ribbens, ‘positions are taken and demarcated in relation to other groups whose position and history are considered equal or inferior, inspiring, competitive or even threatening’ (Grever & Stuurman, Citation2007, p. 65). Grever et al. (Citation2006) conclude that a canon that performs a function in identitarian debates is undesirable: ‘In this canonization, perspectives of groups are excluded, an “us” versus a “them” is constructed. In this process, the power of a particular political and cultural group plays a major role precisely because collective memory is the food source of that historically changeable identity’ (p. 112). Because of the vigorous critique of underrepresentation of woman and minority groups, and because some historians argued that the initial Dutch canon was not precisely representing academic historical discourse, a revised canon was presented by a new committee in 2019 (Kennedy, Citation2020). It was an explicit attempt of this committee to address some of the critique regarding the tension between popular knowledge, and mainstream academic or transformative knowledge (Tuithof et al., Citation2021).

The canon of the Netherlands exists of a topic list of 50 items of ‘important people, objects and events that together show the story of the historical and cultural development of the Netherlands’ (Herijking Canon, Citation2020). The Dutch canon is, however, more than an historical topic list, it is a discourse that materializes through diverse media. A printed book summarizes the 50 items with illustrative texts and associated historical sources. The website (Herijking Canon, Citation2020) makes the canon accessible to all, and it is therefore more frequently used in education. It presents text-discourse in three different levels of language complexity, and also includes videos and graphic representations of canon-items. To avoid criticism of arbitrary selection, each item is used as window to highlight an important element of the local, regional or national history. For instance, Saint-Willibrord is used to demonstrate the expansion of Christianity in the low countries, and a novel of Sara Burgerhart is used to elaborate one the role of women during the age of the Enlightment. The revised canon of the Netherlands intended to stimulate discussion on the international, regional, local or even personal perspectives on the canon, which are seen as equally relevant (Tuithof et al., Tuithof, Citation2021).

A key issue when the canon of the Netherlands was conceived was how it should relate to education. In the instructions that accompanied the first version of the canon of the Netherlands it was stated that it was ‘a tool for teachers to choose topics for their history lessons’ (Rijksoverheid, Citation2006). Hence, it was no mandatory set of curricular topics. Stimulating interest in and discussion about history was thus prioritized above top-down imposing a canonized image of the past. The Dutch canon was initially a tool that schools could use it to help achieve the Dutch teaching standards or other educational goals within their own pedagogical vision. This was later reconsidered. Now it is compulsory in primary education to use canon items for topic selection primary history teaching (Donner, Citation2006), yet teachers remain free to make their own selection or to use discourses that add to or contrast with the canon discourse. In secondary education the canon remains only an instrument of inspiration. A report that examined the implementation of the Dutch canon, concluded that it was indeed seen as non-committing source of inspiration by most teachers. Diverse practices of using the canon had emerged: ‘One teacher uses it to retrieve their own knowledge; another stimulates students to do an assignment for which they have to use the website. A third uses the canon not directly, but indirectly because the canon windows are incorporated into the textbook’ (Kieft et al., Citation2019, p. 47). In other words, the relative non-committal form with which the canon was introduced in the Netherlands, has not prevented teachers from making eager use of it.

elaborates for four canon-items how issues of multiculturality in contemporary Dutch historiography are addressed. The introductory text in the third column is a direct [translated] quote from the website. Each of these examples is further elaborated on the website and in the book with a text of around 500 words and is also documented with images and suggestions for further reading. The examples cited in illustrate how the revised Dutch canon functions as a narrative that operates between mainstream and transformative knowledge. Recent debate on the decolonization of history prompted the second commission to edit the narrative on the Dutch East-Indian Company, which was seen as overly triumphalist, and to add a narrative on the West-Indian company. Here the revised Dutch canon seeks to confront popular knowledge that often still sees these companies as part of the ‘Dutch Golden Age’, with mainstream academic knowledge that for decades seeks to avoid and criticize the Golden Age metaphor (e.g. Huizinga, Citation1941). The discourse on this item includes attention to the role of violence, colonialism, and slave trade. Moreover Anton De Kom, an anti-slavery activist of Surinam descent was included into the revised canon. This illustrates how the Dutch canon sought to integrate elements of transformative knowledge. In recent years a renewed interest in this personage has emerged in the Netherlands which resulted in attention in national news media, new editions of his written works, and memorials (Clara, Citation2023). Although no empirical evidence exists yet, it can be assumed that this discourse influences teaching practices of Dutch teachers.

Table 1. Illustrative items related to multiculturality in the canon of the Netherlands.

A regional canon for the imagined nation of flanders

Upon taking office in September Kieft et al., Citation2019, the Flemish government announced a comparable initiative to that of the Netherlands. Flanders is a separate legislative body, within the federal state of Belgium. A strong political current in the Flemish community strives to the emergence of a more explicit Flemish nation-state. The initiative for a canon of Flanders must be interpreted within this political context (Tollebeek et al., Citation2022). Several historians reacted particularly sharp to the plans (De Paepe et al., Citation2019). Flanders has a long tradition of relative freedom in history education (Wils, Citation2008), hence it was argued that this tradition should not be sacrificed for instrumentalist politics. The Flemish canon initiative seemed to be comparable to Canadian and English initiatives where conservative curriculum reforms intended to reposition the nation in the history curriculum (Gibson & Peck, Citation2018; Taylor & Guyver, Citation2012). Historians advocate a thoughtful handling of the past in history education: students question the past; students reflect critically with and about historical sources; and, students examine the representation and instrumentalization of the past (Seixas & Morton, Citation2012; Wineburg et al., Citation2013). According to some Flemish critics, a historical canon is therefore incompatible with historical thinking, and therefore also with contemporary history education (De Paepe et al., Citation2019). Moreover, it was also argued that the canonization of history would inevitably lead to processes of exclusion, and that therefore a canon of Flanders would stand at odds with citizenship education goals of the general curriculum.

An independent committee of academics and experts was appointed to design the Flemish canon. This committee chose to model its work explicitly to the Dutch example. A canon with 60 items that act as ‘windows’ to give insight in deeper structural elements in society was designed (Gerard, Citation2023b). ‘The committee does not see this canon fulfilling the prescriptive role that a canon had in the past: this is what you have to teach. It sees the canon as descriptive, as a selection of events, texts, persons, social developments, the knowledge of which can be helpful in navigating the world and Flanders of today’ (Gerard, Citation2023a, p. 10). The canon of Flanders seeks to navigate between being an ambitious project of public history, and concurrently remaining aligned with academic historiography. The authors seek to confront popular discourses on the region’s history with mainstream and transformative historiography. It is for instance avoided to refer to Flanders as a nation-state with a distinct history: ‘Today’s Flanders is not the inevitable outcome of “the laws of history”, but the result of an interplay of coincidences, ambitions, interests, conflicts and decisions that were sometimes taken near, sometimes far away’ (Gerard, Citation2023a, p. 4). elaborates four illustrative canon-items that show how issues of diversity and multiculturality are addressed. The introductory text in third column is a direct [translated] quote from the website. Each of these examples is further elaborated on the website and in the book with a text of around 800 words and illustrative primary sources. Comparable to the Dutch example of Anton de Kom, a historical personage was introduced in the canon that was until then virtually unknown to most people in Flanders: Paul Panda Fernana. The biographical narrative of this Congolese intellectual and anti-colonialism activist is used to introduce the history of Belgian colonialism in Congo. Over the past years there has been ample criticism on Flemish educationalists for inadequately addressing colonialism (Bentrovato & Van Nieuwenhuyse, Citation2020). The topic is an example of the tension between popular and academic knowledges. Important academic scholarship of the last decades only slowly finds its way to school knowledge and to popular knowledge. Fernana was until the publication of the canon not covered in Flemish history textbooks, although teacher educators and historians have been taking ample efforts to innovate classic discourse on colonialism in history classrooms (Van Nieuwenhuyse, Citation2021). The introduction of Fernana in the canon might make this transformative academic discourse more accessible than it was before. Shortly after the canon was introduced, educational resources about Panda Fernana appeared on KlasCement, a platform for open educational resources, and he was put on the cover of a newly edited history textbook (Smolderen, Citation2023).

Table 2. Illustrative items related to multiculturality in the canon of flanders.

Beside the example of Panda Fernana and Belgian colonialism, the canon of Flanders addresses issues of multiculturality also in other items. Flanders of today is framed as a multicultural society, and the historical roots of this multiculturality are elaborated extensively. As shown in , attention is dedicated to the emergence of multicultural communities in the mining regions in the first part of the twentieth century, and to the emergence of multiculturality as a result of different waves of migration towards the major cities during the second part of the twentieth century. Although these narratives were already limitedly represented in Belgian history schoolbooks, here also it may be expected that the canon discourse further adds to the alignment of school knowledge, mainstream and transformative academic knowledge.

The pedagogical challenges and purposes of a historical canon

The canon debates show that the pitfalls of drawing a historical canon are multiple. The danger of inside-outside constructions is always present when canons are constructed (Grever & Stuurman, Citation2007). A history canon-discourse can thus result in mechanisms of exclusion towards minority groups in society. If canons are being used for political purposes to legitimize nation-building, as was initially intended be the Dutch and Flemish examples, this risk is present. Yet I will argue that a priori opposition to any form of canonization of the past is not needed. Opposition to any use of canonical discourse in history education neglects the essential role teachers have to fulfill in integrating this discourse into educational dialogue. It is the role of history teachers to navigate their students between the diverging epistemological qualities of the discourses they use (Nitsche & Waldis, Citation2022). History teachers do not simply transmit discourses, they use diverse types of knowledge to target a range of diverse goals in their educational practice by reading, discussing and interpreting them with students. Hence, it is their role to use diverse types of knowledge, from mainstream academic to transformative academic knowledge, and from personal funds of knowledge to popular beliefs. Therefore, when thoughtfully used any kind of historical narrative can provide useful documentation in the history classroom. As Banks shows, in multicultural education it is important for students both to understand some of the fundamental popular and academic knowledges in society, and to reflect upon how these are constructed (Banks, Citation1993, Citation2016). Hence, it is not merely the knowledges that are used in the history classroom that determine the outcomes history education, rather teachers’ instructional design is constitutive for that. Selected knowledges are only a part of this instructional design. How history teachers use knowledge to pursue diverse educational purposes, and how they relate knowledge to their students’ cognitions determines the quality of history education. Consequently, it is essential to understand the diverse purposes for which historical canons might be integrated in history classrooms. Biesta’s framework with three essential purposes of education has been used repeatedly to give insight in the purposes of history education (Nordgren, Citation2021). This framework will be used in the following section. I argue in this section that a historical canon with a limited number of markers which is based on academic historiography can aid to realizing some of the essential purposes of education, in particular in multicultural settings. Therefore, I first introduce Biesta’s framework on the purposes of education Biesta (Citation2010). Subsequently, I clarify the socializing purpose of a historical canon, and elaborate on the importance of subjectivation in implementing any historical canon.

Reflecting on what constitutes good education, educational philosopher Biesta identifies three elementary purposes of education (Biesta, Citation2010). Biesta distinguishes qualification, socialization and subjectification, although he acknowledges that these domains often show a large overlap. Qualification is ‘the teaching of knowledge, skills and understanding and the imparting of skills to judge and discern and enable them to do something’ (Biesta, Citation2012, p. 30). In history education, it is not always clear what it means to be a qualified. Over the last decade the qualification focus has been increasingly on the disciplinary aspect of the subject (Gay, Citation2013). In many Western countries official history curricula are articulated increasingly open, and teachers are encouraged not to pass on national narratives, but rather to actively discuss them in the history classroom (Seixas, Citation1999). Hence, history education seeks to incorporate aspects of training students to master aspects of the profession of historians (Wineburg et al., Citation2013). Biesta argues that the increasing focus on the qualification function of education threatens to come at the expense of other important functions of education. Education that is overly oriented on qualification can, following Biesta, not be seen as good education. ‘The socialization purpose has to do with the many ways in which, through education, we become part of certain social, cultural and political “orders” (…). Through socialization, education brings individuals to existing ways of acting and being. In this way, education plays an important role in the maintenance of culture and tradition’ (Biesta, Citation2012, p. 31). Education is often a process of inconscient acculturation of students into existing orders, it can also be a matter of intended socialization into these orders. Ever since the birth of formal education, intentionally or not, history teaching was used to do so. The nation-state or other existing orders of power have used history education to transmit the knowledge that was seen a contributing to good citizenship. Even though traditionalistic or nationalist aims of history education are being strongly criticized, the socializing function of the subject seems inevitable (Carretero et al., Citation2012).

Barton and Levstik (Citation2004) argued that any history curriculum must address issues of citizenship, although this might as well be a kind of global citizenship education. Any history curriculum that acknowledges its socializing purposes needs to define which aspects of values, culture or tradition would be part of that. In a multicultural environment this aspect of history education uses transformative academic knowledge to challenge traditional historiography. This allows students to understand structures and characteristics of the society in which they live, and to make use of personal or cultural funds of knowledge to gain insight in and discuss how appropriate these structures and characteristics are (Banks, Citation2016). It has been argued that is it important to address for instance issues of racism, colonialism or slavery in order to allow students to understand institutional inequalities (Gay, Citation2013; Ladson-Billings, Citation2014). Hence, the socializing function of history education is not necessarily a vehicle passing on dominant traditions, it can also be an innovative and creative aspect of education.

Finally, Biesta also calls attention to subjectivation. The subjectivation purpose of education addresses the development of the learner as a subject. Necessarily, this relates also to the subject’s relation to others. Biesta states: it is not about inserting ‘newcomers’ into existing orders, but about ways of being that denote a certain independence from existing orders, ways of being in which the individual is not merely a ‘specimen’ of a larger, more comprehensive order. ‘Newcomers’ here should not be understood as immigrants or citizens with a migrant background, but as all young people who in are seen as newcomers in society. This purpose of education is thus to support students’ development as individual and independent subjects. It is complementary to the socializing function of education. Biesta’s model urges educators to consider the individual in educational settings. For multicultural education, this implies that historical discourses of any kind that are used in the classroom are related to those that are educated (Banks, Citation2016).

It is at present unclear to which extent or how history education indeed succeeds to realize this purpose of education. Tutiauxguillon stressed that hardly any empirical data are available on the impact of a curriculum that aspires to teach universal values. ‘Currently we know too little about the effects of this dilemma’ (Citation2007, p. 181). History education that takes inspiration from a historical canon could be at odds with everyone’s right to their own identity. Ribbens (Citation2007) showed, for example, that large groups of young people are rather attracted by the knowledge of their family histories than by national histories. The use of canonical discourse in history education might conflict with students’ individual needs. Consequently, a crucial precondition for the use of the canonical discourse in multicultural history education is that teachers must be able to navigate the frictions that emerge when the socializing and the subjectivation purposes of education conflict. In doing so, it is essential to accept or praise heterogeneity, even when socialization is targeted. Smets (Citation2021) used the concept of negative identity to describe this friction between socialization and subjectivation in history education when using canonical discourse. Negative identity is the indifference or antipathy towards something that is considered essential in a society (Leong, Citation2015). The friction between the socializing and subjectivation functions of history education can only be navigated when teachers allow space for negative identity. History education that does not integrate dissent through negative identity overly stresses the socializing purposes of the subject.

graphically illustrates the role of negative identity to navigate the friction between both these purposes of history education. The Flemish prime minister [minister-president] repeatedly urged citizens to be proud of the region’s history, for instance to be proud of the region’s famous painters like Van Eyck and Rubens (Smets, Citation2021). The canon of Flanders would be an instrument to promote this attitude. This is an illustrative example of how powerful actors in the nation-state express the desire to socialize children. Teachers who engage with these examples of canonical art history face the dilemma of how to balance the socializing function of education with its subjectivation function. In this case introducing students to the nation’s famous painters needs to be balanced with the need for students to develop and express their own sentiments. The subjectivating role of education challenges teachers to engage with their students in conversation about how they can relate to the presented aspects of canonical discourse. When a historical canon acts as a reference point, then it challenges them for instance to consider whether they experience pride towards old painters like Van Eyck or Rubens. In multicultural history education the option of indifference or antipathy would be considered relevant. Teachers navigating the friction between socializing and subjectivation roles of education would acknowledge experiences of antipathy towards the famous painters. They would see this as a valuable expression of negative identity. This is then not seen as a failed attempt to socialize, but rather as a successful balance between socializing and subjectivating students. History teaching becomes sterile or authoritarian when teachers neglect the subjectivation potential of canonical discourse. Canonical history knowledge, whether it be of mainstream academic or transformative nature, must therefore be discussed, interpreted, and where needed also countered or complemented with missing perspectives. This will enable students to see how a canon is always to some extent a representation of existing orders, and hence it will allow them to act as individuals independent of these orders.

Conclusion

Curriculum scholars and historians alike have expressed criticism on historical canons, and their use in history education. They are said to adopt inside-outside perspectives and thus to function exclusionary. In multicultural settings the need for such for canonical historiography is therefore controversial. This article takes a more pragmatic and systemic perspective towards the use of canonical discourse in history education. Arguments in this article describe why a priori criticism vis-à-vis canonical historical discourses upholds a reductionist view on the role of these discourses in history education. A first argument is that Banks’ typology of knowledges allows to gain a more complex understanding of the use of canonical discourse in history education. A second argument is that canonical discourses are only one aspect of teachers’ instructional design. Discerning the qualification, socialization and subjectivation functions of education allows to gain a more nuanced understanding of how canonical discourses may be used in history education. It is concluded that how canonical discourses are integrated in a teacher’s interaction with students essentially determines its eventual added value.

The examples described from the Netherlands and Flanders illustrate how canonical discourses can seek to confront under-evidenced popular knowledges with academic historiography. Hence, when thoughtfully integrated into the curriculum a historical canon can fulfill the function of reference point. Moreover, elements of canonical discourse may support the socializing and subjectivizing functions of education. Debates about democracy, emancipation or justice belong to the core issues of history education, they cannot remain sterile debates about abstract concepts in the classroom but must be illustrated with concrete stories from the past or present. The introduction of specific discourses of transformative nature in the national or regional canons, such as the ones described from Anton de Kom and Paul Panda Fernana, are interesting for multiple reasons. They are elements of transformative academic knowledge that might innovate school knowledge such as history textbooks, and teachers’ interpretation of structural violence and racism. These powerful narratives that for decades remained out of interest of most educators in the low countries, incite history educators to explicitly reflect upon the socializing function of history education. They are elements of transformative academic knowledge that allow students to position themselves as conscious and moral individuals in the society in which they live.

In multicultural history education heterogeneity is positively valued. Frictions may emerge between the socializing and subjectivation functions of the canonical discourses. In this study negative identities are described to understand these frictions. Educators in multicultural history education need to tactfully navigate these frictions to balance its socializing and subjectivizing functions. This is needed to allow those who are educated to become critical and self-conscious citizens of the society in which they live. This study increases our understanding of how content and process interrelate in history education. The implications of this study for theory, research and teaching are that it reaffirms the teacher’s key role in achieving the educational potential of history education. Curriculum scholars have important reasons to discuss and problematize aspects of discourse in history teaching, it is however ultimately up to educational professionals to decide how discourse is used in the classroom and for which purposes. Anyone who acknowledges the socializing and subjectivation role of history education must therefore be able to navigate the frictions that emerge between the different functions for which historical discourse is used.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alridge, D. P. (2006). The limits of master narratives in history textbooks: An analysis of representations of Martin Luther King, jr. Teachers College Record, 108(4), 662–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00664.x

- Bank, J., & De Rooj, P. (2004,). Wat iedereen moet weten van de vaderlandse geschiedenis. een canon van het nederlandse verleden. Nrc Handelblad

- Banks, J. (1993). The canon debate, knowledge construction, and multicultural education. Educational Researcher, 22(5), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X022005004

- Banks, J. (2016). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Barton, K. (2012). Agency, choice and historical action: How history teaching can help students think about democratic decision making. Citizenship Teaching and Learning, 7(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1386/ctl.7.2.131_1

- Barton, K., & Levstik, L. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610508

- Bentrovato, D., & Van Nieuwenhuyse, K. (2020). Confronting “dark” colonial pasts: A historical analysis of practices of representation in Belgian and Congolese schools, 1945–2015. Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education, 56(3), 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2019.1572203

- Biesta, G. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Paradigm Publishers.

- Biesta, G. (2012). Goed onderwijs en de cultuur van het meten: Ethiek, politiek en democratie. Boom.

- Carretero, M., Rodríguez-Moneo, M., & Asensio, M. (2012). History education and the construction of a national identity. 1–14.

- Carretero, M., & van Alphen, F. (2014). Do master narratives change among high school students? A characterization of how national history is represented. Cognition and Instruction, 32(3), 290–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2014.919298

- Clara, V. (2023). Wie was anton de kom?. NPO kennis. https://npokennis.nl/longread/8086/wie-was-anton-de-kom

- Counsel, C. (2017). The fertility of substantive knowledge: In search of its hidden generative power. In I. Davies (Ed.), Debates in history teaching (pp. 80–99). Routledge.

- De Paepe, T., De Wever, B., Janssenswillen, P., & Van Nieuwenhuyse, K. (2019). Dienstmeid of kritische vriendin? waarom een vlaamse canon geen goed idee is voor het geschiedenisonderwijs. Karakter: Tijdschrift Van Wetenschap, 17(68), 1.

- Donner, J. P. H. (2006). Besluit kerndoelen onderbouw voortgezet onderwijs.

- Fordham, M. (2016). Knowledge and language: Being historical with substantive concepts. In C. Counsel, K. Burn, & A. Chapman (Eds.), Masterclass in history education. transforming teaching and learning (pp. 43–57). Bloomsbury academic.

- Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through cultural diversity. Curriculum Inquiry, 43(1), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/curi.12002

- Gerard, E. (2023a). Canon van vlaanderen. Rapport van de commissie aangesteld door de vlaamse regering. https://www.canonvanvlaanderen.be/content/uploads/2023/05/Canon_Rapport-aan-de-minister_7MEI.pdf

- Gerard, E. (Ed.). (2023b). De canon van vlaanderen in 60 vensters. Borgerhoff & Lamberigts.

- Gibson, L., & Peck, C. (2018). The place of history in the alberta social studies curriculum. Active History. https://activehistory.ca/2018/05/alberta-social-studies-curriculum/

- Grever, M. (2005). Wat doen we met de canon? In A. Wilschut (Ed.), Zinvol, leerbaar, haalbaar (pp. 21–30). Vossius Pers.

- Grever, M., Jonker, E., Ribbens, K., & Stuurman, S. (2006). Het behouden huis. commentaar op de canon van nederland. In M. Grever (Ed.), Controverses rond de canon (pp. 106–116). Van Gorckum.

- Grever, M., & Stuurman, S. (2007). Beyond the canon. history for the twenty-first century. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230599246

- Grever, M., & Van der Vlies, T. (2017). Why national narratives are perpetuated: A literature review on new insights from history textbook research. London Review of Education, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.18546/LRE.15.2.11

- Herijking Canon, C., & v. N. (2020). Open vensters voor onze tijd. de canon van nederland herijkt. Stichting entoen.nu.

- Hogg, L., & Volman, M. (2020). A synthesis of funds of identity research: Purposes, tools, pedagogical approaches, and outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 90(6), 862–895. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320964205

- Huizinga, J. (1941). Nederland’s beschaving in de zeventiende eeuw. Tjeen.

- Jonker, E. (2006). Sotto voce. identiteit, burgerschap en de nationale canon. In M. Grever (Ed.), Controverses rond de canon (pp. 4–28). Van Gorcum.

- Kennedy, C. (2020). Canon van nederland.

- Kieft, M., Buynsters, M., Damstra, G., & Bremer, B. (2019). De canon van nederland vervolgonderzoek 2018/19 (). Oberon. De Canon van Nederland Vervolgonderzoek 2018/19. http://docplayer.nl/136206519-De-canon-van-nederland-vervolgonderzoek-2018-19-marleen-kieft-michael-buynsters-geertje-damstra-benjamin-bremer.html

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A.K.a. The remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

- Leong, N. (2015). Negative identity. Southern California Law Review, 88(6), 1357–1419.

- Mierwald, M., & Junius, M. (2022). Thinking aloud about epistemology in history: How do students understand the beliefs about history questionnaire? Historical Encounters, 9(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.52289/hej9.103

- Nitsche, M., & Waldis, M. (2022). Narrative competence and epistemological beliefs of German Swiss prospective history teachers: A situated relationship. Historical Encounters, 9(1), 116–140. https://doi.org/10.52289/hej9.107

- Nordgren, K. (2021). Powerful knowledge for what? history education and 45-degree discourse. In A. Chapman (Ed.), Knowing history in schools. powerful knowledge and the powers of knowledge (pp. 152–176). UCL press.

- Ribbens, K. (2007). A narrative that encompasses our history: Historical culture and history teaching. In M. Grever & S. Stuurman (Eds.), Beyond the canon. history for the twenty-first century (pp. 63–76). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rijksoverheid. (2006). Wat is de canon van nederland?.

- Seixas, P. (1999). Beyond ‘content’ and ‘pedagogy’: In search of a way to talk about history education. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(3), 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/002202799183151

- Seixas, P., & Morton, T. (2012). The big six historical thinking concepts. Nelson education.

- Smets, W. (2021). Dienstbaar verleden? hoe een canon van vlaanderen kan bijdragen tot goed onderwijs. Tijdschrift Voor Onderwijsrecht En Onderwijsbeleid, 3, 250–257.

- Smolderen, H. (2023). Sapiens 5. Van In.

- Stuurman, S. (2006). Van nationale canon naar wereldgeschiedenis. In M. Grever (Ed.), Controverses rond de canon (pp. 59–89). Van Gorcum.

- Taylor, T., & Guyver, R. (2012). History wars and the classroom: Global perspectives. IAP.

- Tollebeek, J., Boone, M., & Van Nieuwenhuyse, K. (2022). Een canon van vlaanderen. KVAB Press.

- Tuithof, H. (2021). Nabeschouwing op de herijking van de canon van nederland. Tijdschrift Voor Geschiedenis, 134(2), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.5117/TVG2021.2.009.TUIT

- Tutiaux-Guillon, N. (2007). French school history confronts the multicultural. In M. Grever & S. Stuurman (Eds.), Beyond the canon. history for the twenty-first century (pp. 173–187). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Nieuwenhuyse, K. (2021, The colonial past in Belgian history education since 1945. Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’europe [online]

- Wills, J. S. (2001). Missing in interaction: Diversity, narrative, and critical multicultural social studies. Theory & Research in Social Education, 29(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2001.10505929

- Wils, K. (2008). De verdampte canon en de gebetonneerde bron. geschiedenisonderwijs in belgië in historisch perspectief. In M. Depaepe, B. Henkens, & M. Leon (Eds.), Over het mooie en het nuttige. bijdragen over de geschiedenis van onderwijs en opvoeding. liber amicorum aangeboden aan mark d’hoker (pp. 239–254). Garant.

- Wilschut, A. (2002). Historisch besef als onderwijsdoel.

- Wineburg, S., Martin, D., & Monte-Sano, C. (2013). Reading like a historian. teaching literacy in middle and high school history classrooms. Teachers college press.