Abstract

Tanzanian legislation for women’s rights is a product of decades of indigenous women’s struggles and considered amongst the most progressive in Africa. However, implementation has been problematic and some elements in the current discourse appear to push back against gender equality with an essentialist framing of women and men as naturally different. This paper draws on the perspectives of 144 women and 144 men, in four rural communities in different regions of Tanzania, to build an understanding of how they perceive gender equality, and how their perceptions relate to decision-making, women earning incomes, women as homemakers, and control over assets. Understanding gender as a performance we contextualise our analysis through a historical overview of women’s struggles to secure rights from colonial times to the present day. We find that while local discourse appears to embrace the idea of gender equality, practice remains quite different with the threat of sanctions restricting the scope for re-negotiation of gender. The paper demonstrates how the continuous performance, reproduction and renegotiation of gender takes place as part of everyday life, as women and men seek to secure their personal well-being in a context of limited cultural and economic options.

1. Introduction

In 2006, the Global Gender Gap Report ranked Tanzania number 1 of 115 countries, with respect to the women’s economic participation sub-index (and 24th for its combined ranking across a range of indicators) (World Economic Forum, Citation2006). Ellis, Blackden, Cutura, MacCulloch, and Seebens (Citation2007) praised the Government and civil society for developing numerous policies and strategies in support of gender equality and women’s empowerment. In the 2018 Global Gender Gap Report, though, the women’s economic participation sub-index ranking for Tanzania had fallen to number 72 (and 71 for its combined ranking across a range of indicators) (World Economic Forum, Citation2019). The discrepancies between rankings only 12 years apart speak perhaps to a naive optimism that creating progressive policies would translate rapidly into women’s economic and other forms of empowerment. In fact, almost the opposite has happened. The Human Rights Watch Global Report (Human Rights Watch, Citation2019) notes that girls, women, and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBTQI) people face increasing discrimination and harassment in Tanzania. In 2017, the Government overturned four decades of policy when it banned pregnant girls and young mothers from attending school. Many schoolgirls routinely face forced pregnancy testing. In 2018, the Government suspended USAID-supported messaging on birth control. Consensual adult same-sex conduct is punishable with up to life in prison, and a severe crackdown on LGBT communities initiated by the current government continues (Human Rights Watch, Citation2019). In agriculture, the gender productivity gap (the difference between the average value of agricultural output per hectare/acre on women-managed and on men-managed plots) remains large. The World Bank (Citation2015) estimates that the gender productivity gap in Tanzania amounts to USD 105 million (0.46% of GDP), and that closing the gender productivity gap could lift 80,000 Tanzanians out of poverty each year and eliminate malnourishment in the same number. However, TGNP Mtandao (Citation2018), a transformative feminist umbrella organisation, notes that the Government’s Vision 2025 includes no measures to address the agricultural gender productivity gap. How are we to make sense of what is happening? Why is there a tendency for gender to take on an essentialist aspect, creating women and men as having clearly binary identities with different responsibilities, roles, and rights?

Against this backdrop, we examine how women in the study communities are taking advantage of new opportunities for income generation and in relation to the gender equality narrative promoted over recent decades. We explore how women’s response to these opportunities is shaped by local gender norms; and whether norms are changing as a consequence of women’s engagement. We draw upon Butler’s work (Citation1988) which suggests that gender is performed: it is constituted from repeatedly performed acts. Gender, she argues, is also performative: the very idea of gender arises from the repetition of these repeatedly performed acts. That is to say, gender is created by its own performance. It is so successful in obscuring its non-natural origins that it actually comes to appear natural, obvious and important (Morgenroth & Ryan, Citation2018). At the same time, because gender is non-natural, its very performance also allows scope for renegotiation (Butler, Citation1988).

We use these insights from Butler’s conceptual model to help us analyse qualitative data produced through the Gennovate research initiative (Badstue et al., Citation2018; Petesch et al., Citation2018) into gender norms and agency in four farming communities in different parts of Tanzania. We hypothesise that although gender is continually being re-enacted and reproduced, spaces are emerging for women and men to renegotiate gender. We investigate the nature of these spaces, and we also investigate the degree to which injunctive sanctions, which arise from local normative understandings of what it means to be a man or a woman in these communities, impose restrictions on renegotiation.

We open by presenting some of Butler’s ideas. We then provide a short historical overview of how the identities of Tanzanian women have been contested and shaped during the colonial era and following Independence. This allows us to gain an appreciation of gender as a process in Tanzania. Women have long sought a variety of identities, and likewise have had identities imposed upon them. Next, we describe our research methodology and study sites. We then turn to our findings. In the discussion, we reflect on the usefulness of Butler’s model to our interpretations of the data. We also bring an analysis of power to help explain how normative sanctions continue to structure gender behaviours and restrict the scope for change.

2. Conceptual framework: the acts of gender create the idea of gender

Butler (Citation1988) writes that gender is not an essential, biologically determined quality or an inherent identity. ‘Gender is not a fact, the various acts of gender create the idea of gender, and without those acts, there would be no gender at all’ (Butler, Citation1988, p. 522). Rather than being something one is, gender is something one does, or performs. Gender identity is not an inner truth but is rather a product of repeated gender performance [our emphasis] (Morgenroth & Ryan, Citation2018). The constant repetition of gendered performance possibly involves some degree of conscious artifice (Meyerhoff, Citation2015). However, continual reproduction of gender also means that it becomes performative. In other words, repeated performance creates the very idea of gender itself and the illusion of two natural, essential selves. ‘Individuals act as women and men. This creates the categories of women and men (Morgenroth & Ryan, Citation2018). In this way gender becomes naturalised. ‘(Gender) is woven so tightly into the social fabric that it seems like a necessary part of reality rather than a contingent production of history’ (Jones, Citation2018).

The authors of this article interpret these ideas as meaning that the interaction between repeatedly performing gender, and gender as performative, leads to a continual co-creation of each other. This makes gender exceptionally robust. These interactions create norms, which provide ‘scripts’ for gendered behaviours, that are endlessly renewed. According to Butler (Citation1988), when a person acts a specific gender, this is an act that began before they arrived on the scene. It is like a script, which ‘survives the particular actors who make use of it, but which requires individual actors in order to be actualized and reproduced as reality once again’ (Butler, Citation1988, p. 526). Butler argues that although gender is necessarily acted and is not something real, gender is forced to comply with a model of truth and falsity. This model serves social policies of gender regulation and control. Performing one’s gender ‘wrong’ triggers direct and indirect punishments. Performing it ‘right’ provides reassurance that there is an essentialism of gender identity after all (Butler, Citation1988). This leads us straight back to the opening of our paper, where we presented data that suggests, that far from moving towards gender equality, current Tanzanian policy is moving towards promoting an essentialist understanding of gender, whereby different behaviours for women and men are expected – and policed. Consequently, different life outcomes are countenanced even though there are terrible costs to the nation, for men as much as for women, as the price it is necessary to pay to maintain gender difference and male superiority.

Morgenroth and Ryan (Citation2018) explain that sanctions do not exist by chance. Rather, they argue, sanctions are the tools of a system, which is trying to reproduce and sustain itself. This is a patriarchal system of compulsory heterosexuality, which is proscriptive – it represses deviating gender performance, and prescriptive – it demands hetero-normative gender performance (Morgenroth & Ryan, Citation2018). In all this, Butler does not deny people agency. Since gender is constructed, it is neither completely arbitrary and free, nor completely determined. This leaves room for re-structuring, subversion, and for disrupting the status quo (Morgenroth & Ryan, Citation2018).

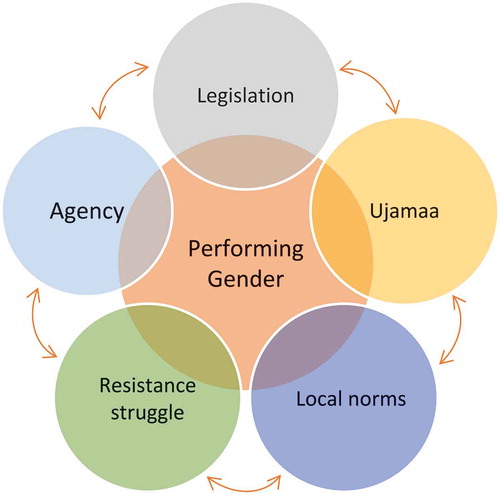

This article proceeds as follows. In the literature review, below, we set the stage for our fieldwork findings. We examine how gendered interactions in selected domains contribute to the performance of gender in Tanzania. We start with women’s roles in resisting colonialism, and then move onto the period of African socialism termed Ujamaa. We then highlight some insights on women’s relationship to land and food management. We see how all this feeds into the contrary ways in which gender is expressed in national legislation and policy. visualises how key domains interact and influence each other to produce how women and men ‘perform gender’.

3. Literature review

This necessarily short overview sets the scene for reporting from our four study communities.

3.1. Gender in national narratives

Women were important players in the struggle for Independence. However, analyses by Kinunda (Citation2017), Mbilinyi (Citation2016), Geiger (Citation1996) and Brain (Citation1978) suggest that the role of women has been largely suppressed in the way the past has been recalled in national narratives. Mbilinyi (Citation2016) explores history as process: it is continually being negotiated between women farmers; powerful local classes; pre-colonial, colonial, post-colonial political and economic institutions; and actors – including men – at community level. Kinunda’s (Citation2017) study shows that during (and indeed after) the colonial period women negotiated their labour power in cash cropping and protested actively against detrimental events in relation to land and agriculture. Geiger (Citation1996) argues that women, during the 1950s, did not only respond to how the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) defined an emerging national consciousness. Many thousands of women, acting across tribal lines, were key players in constructing ‘what nationalism came to signify for many Tanzanian women and men’ (Geiger, Citation1996, p. 465). Brain (Citation1978) concurs largely with these analyses. He emphasises that the colonial – followed by the post-colonial – authorities in Tanzania exacerbated gender inequalities. In pre-colonial society women and men held different roles, with women often holding high office and enjoying high status as food producers. However, Europeans introduced concepts around Victorian ideals of ‘gentility’ for women at the same time – for example that women are homemakers – alongside introducing cash crops which greatly increased demands upon women’s labour. These colonial conceptualisations of women’s roles remain powerful today (Brain, Citation1978).

3.1.1. Gender in Ujamaa

Modern Tanzania was formed in 1964, when mainland Tanganyika merged with Zanzibar. Tanganyika won Independence in 1961 and Zanzibar in 1963. Ujamaa (literally ‘familyhood’, 1964–1975) aimed to transform Tanzanian society through returning it to pre-colonial values. The process included villagisation, collective farming, nationalisation of industry and banks, increased self-reliance at a personal and national level, and the development of a strong national culture (Lange, Citation1995; Mbilinyi, Citation1972). Ujamaa, according to Mbilinyi, ‘through the reconstitution of agrarian relations, offered poor rural women a chance to become aware of ‘the contradictions of their own lives and […] to realise their own true abilities and potentialities’ (Citation1972, p. 72). Fortmann (Citation1982) acknowledges that the transformative potential of Ujamaa for women was realised at times. However, although women could acquire land under Ujamaa, they did not always benefit. This is because ‘structures for equality […] tended to be overwhelmed by male-dominated tradition’ at the village level (Fortmann, Citation1982, p. 167). Women often did not get good land, or sufficient land, nor did they have much control over their produce (Fortmann, Citation1982). Women’s work in the field was often unrecognised (Croll, Citation1981). Lal (Citation2010) argues that the Tanzanian state’s understandings of the rural family and the Ujamaa project ‘were deeply riddled with internal tensions.’ Distinctive gender roles for women and men were normalised, and a generic ideal of the nuclear family was celebrated (Lal, Citation2010). Women were promoted primarily as homemakers; it was never suggested that men could engage in house and care work (Croll, Citation1981). In reality, Tanzanian women have always moved in and out of motherhood, working in the field and off-farm (Lal, Citation2010). Women’s multiple roles were recognised at the time by some observers: ‘The African woman thinks of herself as more than a wife and mother. She is a cultivator, a weaver, a trader, and her occupational role is part of her self-image’ (Mbilinyi, Citation1972, p. 60). Despite this, strengthening women’s equality was never explicit in Ujaama official policy (Fortmann, Citation1982).

During the 1980s, Ujaama was largely reversed. Men increasingly migrated to urban areas and rural women took on many tasks previously considered men’s (Mbilinyi, Citation2016). Land became commercialised and increased rapidly in value during the 1990s and into the 2000s.

3.2. Changing norms: women’s struggles for land

The conflicting and complex ways in which men and women, and the national State, sought to perform gender during the struggle for Independence and during Ujamaa, is reflected in contestation around normative conceptions of ‘who owns land’.

Although under Ujamaa women had had the right to own land, the issue of ownership of land between husband and wife was excluded from legislation in the National Land Policy of 1995. Women’s organisations then mobilised for equal treatment under the law. Their struggles resulted in the Land Act and the Village Land Act, 1999, and the Courts (Land Disputes Settlements) Act of 2002. These are considered amongst the most progressive legislation in Africa (Pedersen & Haule, Citation2013). Legally, women may hold, own and dispose of property, and women have the same land rights as men. Laws provide for strong protections of women landowners, recognise a wife’s right to household land upon widowhood or divorce, prevent village land councils from discriminating against women, and allocate to women a certain number of seats on the councils, which administer occupancy rights and adjudicate land disputes in rural areas (Pedersen & Haule, Citation2013). However, these rights are rarely realised. Customary land tenure continues to vest control of property in men across Tanzania: in such systems women’s rights to land are generally dependent on maintaining their roles as wives or daughters (Ewans School of Public Affairs, Citation2011). Women and men generally have little knowledge of national law, local institutions have low technical and financial capacity to implement national legislation, and women’s participation in community level decision-making bodies is weak (Sutz et al., Citation2019). Daley’s (Citation2005a, Citation2005b) study of the relationship between land and social change in Tanzania from colonial times to the present illustrates how gendered differences in wealth and education, as well as marital status and kinship, influenced and continues to influence women’s ability to formalise their rights to land and other assets. Thus, women across Tanzania are highly vulnerable to dispossession of land upon the death of their husband or separation (Dancer, Citation2015; see also Schlindwein et al., Citation2020). The negative impact of norms has been sharpened by the commercialisation of land from the 1990s to the present day. Between 2000 and 2015, foreign and/or national investors acquired 1,321,731 ha of land with, in many cases, few benefits to the local population (Dancer & Sulle, Citation2015). Such investments have sharply increased the value of land and thus the potential for contestation (Kinunda, Citation2017; Mbilinyi, Citation2016). Furthermore, families headed by women tend to be poorer than those headed by men, and ‘only those [women] both “without men” and with independent means [are] able to make most use of the land market’ (Daley, Citation2005b, p. 558).

Women have continued the struggle for gender equality in land. Over the past few years, for instance, the Tanzania Women Lawyers Association (TAWLA) has been working with the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) and other national and international organisations to support villages to adopt ‘gender-sensitive’ bylaws. This ongoing project has been successful in around 130 villages across six districts, including all villages in the first district (Sutz et al., Citation2019).

3.3. Naturalising gender: relationships between violence and women’s nutrition

A study conducted in the Dodoma region of Tanzania (Bonatti, Borba, Schlindwein, Rybak, & Sieber, Citation2019; Schlindwein et al., Citation2020) found that women lived within a complex set of domestic relationships between violence, food, and malnutrition. Both women and men had clear concepts of femininity and masculinity, which they literally acted out in the study through participation in Forum Theatre drama exercises. Men associated masculinity with decision-making, and strongly resented women asserting power within the household. When women are ‘over-empowered’, men feel their ideas are not respected, and that they need to beat women to restore order and ensure appropriately submissive behaviours. Women felt isolated and shamed when physically chastised and could not call on anyone for help. They felt it important to express their femininity through ensuring that they could provide their husbands with more to eat, and more meat, than other household members (though from a nutritional point of view children and women of reproductive age have greater need of good nutrition). Being feminine was associated with eating later, eating less, and eating less meat. However, women did not see their performance as good wives at the table as a way to avoid violence. Rather, they argued that by prioritising their husbands at the table they were expressing their love for him (Bonatti et al., Citation2019). Returning to Butler’s analysis, this is a perfect example of how gender becomes performative: the very practice of gender creates gender. Its non-natural origins are obscured through myth-making around the concept of a good wife. The role of sanctions is also clear in this example. Women, who men perceive as stepping out of line – primarily through posing a challenge to male dominance in decision-making – are subjected to physical violence. The case exemplifies the idea that effective gender performance is an intensely personal affair, which individual women need to ‘do right’ (hence they have no right to ask others for help). As such, the performance of gender – and gender-based violence – is depoliticised.

3.4. Gender in national legislation and policy

The overview so far shows that ‘how to do gender right’ in rural Tanzania has been contested for decades and is still being contested. As a consequence, different understandings of what it means to be a woman, or a man, permeate national legislation. Performance is not cohesive.

The Constitution of 1997 prohibits discrimination against women. Tanzania has signed all major international and regional gender equality protocols and instruments. It has ratified the 2030 SDG Agenda and the long term 2063 Agenda (both of which include commitment to gender equality). The country has made some efforts to align implementation of the SDGs with national planning frameworks. However, the current National Development Plan does not fully capture gender equality issues and women’s empowerment. In fact, only half a page from 124 pages is dedicated to discussion of gender equality – with a few gendered indicators on other pages (Ministry of Finance and Planning, Citation2016). By way of contrast, the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (Citation2016) in its ‘Country Gender Profile’(139 pages) notes considerable weaknesses with respect to legislation in employment, property ownership and credit, and weak mainstreaming of gender in planning and budgeting at sector level. Inadequate gender-disaggregated data in key economic sectors prevents a good grasp of the situation of women and gender relations and hampers monitoring (Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, Citation2016). Outside observers note the overall lack of alignment between polices to advance gender equality and sector-specific policies of government ministries – as noted above with respect to land legislation (Acosta, Ampaire, Okolo, Twyman, & Jassogne, Citation2016; USAID, Citation2018). TGNP Mtandao asserts: ‘gender mainstreaming continues to remain a lip service, whereby the Government creates national gender instruments, but commits insufficient funds to attain them’ (Citation2018). Taken together, these observations point to a tension at the heart of government. This tension arguably arises from the long-standing contestations around what a man, and a woman, should be and should do, that have characterised Tanzania over the past century and more.

We now turn to our study to explore these issues further. We present the methodology and study communities before moving to the findings and discussion.

4. Materials and methods

The overall focus of the study, conducted in 2015, was upon understanding – from the respondents’ point of view – how gender norms and agency shape the capacity of men and women to learn about, adopt and benefit from agricultural innovations (Badstue et al., Citation2018). The selection of study communities was based on purposive, maximum diversity sampling focused on four variables: high or low gender gaps (assessment of educational achievements, income-generation, mobility, and so forth) and high or low economic dynamism (assessment of markets, infrastructure, services and so forth). In each community, research teams conducted fifteen research activities, all but one disaggregated by gender. These included six focus group discussions (FGDs) with women and men in low- and middle-income categories (aged 25 to 50), and with young women and men (aged 14 to 24). Also, four semi-structured life-story interviews (two with women and two with men), and four semi-structured individual interviews with recognised women and men agricultural innovators, as well as a community profile (with both genders) were conducted. Study participants reflected on a wide variety of questions related to, for example, gender norms and household and agricultural roles; gender norms surrounding household bargaining over livelihoods and assets; labour market trends and gender dimensions; women’s physical mobility and gender norms shaping access to economic opportunities and household bargaining (see Petesch et al., Citation2018 for further discussion of the methodologyFootnote1). In total, the article draws on the perspectives of 144 women and 144 men living in four rural communities.

provides an overview of selected characteristics in each community. All community names are anonymised. Each community generally grows a mix of grain-based food security crops, vegetables, tree crops, and some other cash crops. Considerable ethnic diversity contributes to a mix of matrilineal and patrilineal kinship arrangements. Ethnic community and religious affiliation were noted but did not in themselves form selection criteria and thus comparative analysis on these data points is not possible.

Table 1. Characteristics of study communities

The presentation of findings focuses on capturing understandings and meanings from the point of view of the respondents met during the study and thus uses direct quotes in many cases. Relying on respondent terminology and framing of some key concepts aims to provide the respondents with some agency in directing the analysis (Farnworth, Citation2007). This approach is based on the epistemological understanding that the nature of knowledge means that there is no ultimate truth, but rather partial knowledge and multiple truths. Feminist enquiry aims to challenge binary oppositions, thinks relationally, and considers that research is never a neutral process (Feldman, Citation2018).

5. Results

The findings are presented as follows. First, we explore concepts of gender equality and how these are expressed in intra-household decision-making. This section helps to contextualise those, which follow. Second, we provide an account of men and women’s responsibilities for income generation. Third, we examine the concept of women as homemakers, and fourth, we assess the reality that men are primary asset holders and managers.

5.1. Gender equality

Respondents in the low-income focus groups were asked to discuss their understanding of gender equality. Overall, both men and women support the concept of gender equality, but they differ in their understandings of what this entails.

Although the communities of Medu and Kilosha were characterised as having high gender gaps, low-income men generally viewed gender equality positively. One man in Medu argued that ‘Equality helps to make a woman feel comfortable as a human being.’ It was widely argued that gender equality can help to strengthen relationships, which ‘increases happiness in the family’ (Kilosha). The sense that harmonious relationships are important were broadly shared by men and women across the data set. Low-income men respondents explicitly linked harmony to improved economic outcomes. ‘If a man and a woman don’t agree there is no development’ (Mogorowi). ‘Gender equality is good because both respect each other and whatever they do succeeds’, and ‘Gender equality increases production since both are able to participate in farming or productive activities’ (Tanwa). Low-income women focused less than men on how gender equality can enhance income and productivity, and more on the timesaving benefits. Women in Kilosha, for example, argued that gender equality ‘saves time because if a woman is working on one activity and the man on another activity, then work is done in a reasonable time’.

Four low-income men’s FGDs, and three low-income women’s FGDs, asserted that violence against women and girls fell over the decade prior to the study. They ascribed this to awareness-raising efforts by NGOs and more effective enforcement of laws against domestic violence. Two women respondents, in Tanwa and Medu, associated gender equality with reduced violence, commenting respectively ‘This means stopping dictatorship of a man over a woman. In the past men used to dominate women. Through equality this habit ends’, and ‘Equality is good because it protects women against mistreatment.’

The study assessed whether positive attitudes towards the concept of gender equality is reflected in actual intra-household decision-making processes. Evidence of collaborative decision-making is weak. Some low-income men in Tanwa argued that ‘in the past men used to decide on everything concerning the family, but with equality both a man and woman can decide.’ However, such sentiments were rarely expressed. Although some low-income women in Mogorowi argued that, a husband ‘must be able to communicate with his wife. They must discuss their income and expenditure distribution together’, it was much more common for low-income men to argue that a wife should be humble, hospitable, ‘listen carefully to whatever she is being told’ (Medu), and demonstrate respect for her husband as well as ‘provide satisfactory answers to whatever question’ men may pose (Kilosha).

Across the four communities, middle-income women agreed that most decisions are taken by men. A woman in Mogorowi argued that some women never have full decision-making power, because they are ‘dependent on men for almost everything.’ Women in Tanwa considered ‘Women make decisions under fear. In order for a woman to make decisions, she has to seek approval from the husband so that her decision can go right.’ A different nuance was that collaborative decision-making in itself reduces women’s capacity to take decisions. ‘Once a woman gets married, her freedom to make decisions decreases. Most issues are decided upon jointly’ (Mogorowi). The implication here is that women have less agency in decision-making processes, particularly over expenditure decisions – even if they are ostensibly collaborative in some cases.

Respondents illustrated the weak agency of married women by describing how their income-generation potential can be circumscribed. One woman in Mogorowi said, ‘They make you grow crops to eat at home. You cannot have cash crops, that will allow you to become rich.’ Women in Tanwa noted that, ‘Most men do not trust their wife. Even if she is doing business, a man wants to control her money. This forces some women to separate and live alone so as to have freedom in doing their private activities’. Another added, ‘As a woman, if you are seen having any amount of money, the first question your husband asks is – where have you got that money from? Even if you happen to provide good reasons, men never believe you.’

Some separated women enjoyed their autonomy. A single woman in Mogorowi said, ‘When I was married most decisions were made by my husband. Even the little decisions I used to make were undermined by him. Today however I can make full decisions. Men are dictators over women. They normally consider women’s decisions are useless’. Single women from Kilosha focused on their ability to manage money. ‘Now I make decisions without any obstacle. When I was living with the husband, despite the fact, that everyone works to make money, it was my husband who made decisions over income. After the harvest he was the one to sell the produce and at the end of the day I did not benefit from the income we made.’ Another added, ‘We used to harvest what was enough for us to consume as a household and my husband used to sell what remained to get some money. At that time, I had no control over money.’

5.2. Men and women’s responsibilities for income generation

Across the four communities the normative association between men and their role as economic provider and decision-maker was deep-rooted and strong. While women are widely expected to contribute to income generation, economic success on their part can challenge men’s position. One reason why men across the data set asserted control over income may be normative associations between men and their role as economic provider.

In Tanwa, low-income men and women argued respectively that men are expected to ‘cater for household needs’, and to ‘struggle to provide household necessities.’ Respondents in Kilosha made very similar remarks, with men adding it was a male responsibility to pay for the ‘education of children, health costs and diet-related issues.’ Yet it was common for respondents to comment that women had to earn money to provide for their families. Indeed, in all communities almost all women were engaged in a wide range of on-farm and off-farm income generating activities. On-farm activities include cropping, poultry and livestock rearing, as well as selling crops like bananas, mangos, oranges, vegetables, maize and rice, and preparing maize beer. Off-farm work in all study communities includes casual work as farm labourers and selling other people’s produce at the market. In Kilosha, a number of women work on a large horticultural estate and in Medu, many women have found work in the lively hotel and service sector. In Tanwa, which experiences particularly low economic dynamism, programmes supporting vulnerable families, and the establishment of a sunflower processing plant, is providing economic opportunities for women and men.

5.2.1. Women earning their own income ‘suffer’

Although off-farm income-generation opportunities are opening up in all communities, women involved in paid labour were widely described as suffering and struggling. Low-income men in Mogorowi explained ‘the community has no problem with a woman struggling to make her life.’ Low-income men in Kilosha argued that ‘People sympathise with her, because she is working hard for her family needs’, and ‘They admire her for working far away to sustain the family.’ Women respondents in Mogorowi and Kilosha explained, ‘Women selling vegetables in the market is a common practice here. No one worries about it’ and ‘This is normal practice. Actually, this is what women do.’

One reason why women are considered to struggle when they take on paid work, or market products, is their general lack of control over expenditure decisions – particularly when married – as noted above by low-income respondents. Discussions with middle-income men and women centring on a hypothetical vignette-based exercise whereby a man previously sold vegetables the wife had grown – because he expected his wife to focus on household work – to a new situation where the wife herself joins a women’s marketing group, revealed strong fears among men that they will lose access to money. ‘The husband will take this decision as a way to stop him from getting the income he has been earning’, according to men. Women added, ‘He will use all reasons to prevent his wife from going to sell vegetables on her own. He will tell her to remain doing domestic activities.’ In all four communities respondents agreed with these assessments.

Another hypothetical vignette focused on a couple, where the wife has become successful in her market enterprise. Women and men agreed that the husband, who broadly agreed with his wife’s entrepreneurial spirit, would appreciate his wife’s financial success. However, it was widely agreed that such a man would be concerned. Men respondents said, ‘He will accept what has happened, but he will worry about the future. Because of her wealth his wife can turn against him any time’ (Medu) and ‘He will fear that in future he will have no say when it comes to making decisions over the accumulated resources’ (Kilosha). The concern that a wife may ‘turn against’ the husband was linked to a widely held belief that an economically successful wife may marry another man, or court other men to obtain money.

5.3. Women as homemakers

A second reason why women, who work outside the home, are considered to suffer and struggle is that women are strongly associated with household, parenting and care roles in all communities. This has considerable implications for the ability of women to balance their time. Yet, normatively, the thought of a husband conducting domestic tasks and care work was viewed ambivalently.

Women and men in low and middle-income categories agreed, that working women must never neglect their childcare responsibilities. At the same time, low-income women in particular argued that gender equality should translate into stronger participation by men in household and care work. ‘Gender equality means giving freedom to the wife to work in business, as well as assisting each other in the responsibility of taking care of the children’ (Tanwa). ‘Gender equality means, that if the woman has gone for harvesting in the farm, the man can help in caring for the children’ (Mogorowi). In some cases, men are contributing more. Women in Mogorowi said, ‘Women and men are able to work together now, different from the past where women seemed to work alone in most of the domestic activities’, and that ‘Gender equality is good, because today men are encouraged to take children to the clinic’ (Medu). However, men did not make any statements relating to their willingness to participate in household work.

A third hypothetical vignette-based exercise, whereby the wife is a successful market vendor and her husband manages housework and childcare, led respondents to expect both parties losing respect. Regarding the wife, women respondents explained, that ‘The community will consider her a woman with no concern for her family’ (Mogorowi). She will be judged for making him do activities that are ‘not worthy to be done by a man’ (Medu), and for making him look like a ‘house girl’ (Tanwa). Accusations of witchcraft would be made, and men in the village would shout at the wife, that ‘what she does is no good.’ According to men respondents, the husband would be despised, because ‘he does the opposite of what men are supposed to do’ (Medu). ‘It is abnormal, and it would look like the wife paid bride-wealth for the man’ (Mogorowi). Both women and men agreed that the husband would not have time to engage in social occasions with other men, because he would be too busy working on his chores. Despite the strong condemnation, it is not clear whether women would in fact welcome such a husband. Rather, the comments make it clear that men who openly engage in tasks associated with women are marginalised and scorned.

5.4. Men as asset holders and managers

Although low-income men in Medu argued that gender equality meant ‘women can share family assets, not as in the past whereby assets were only reserved for men’, in general women were recognised to have very low command over assets. Women were considered entitled to use assets during their marriage, and in so doing, contribute to the family’s livelihoods and further asset creation. However, when the marriage ends, whether due to death of the spouse or separation, most women have to leave their households empty-handed, and have no call upon the land. A middle-income woman in Tanwa said, ‘I separated from my husband, and I had to leave all the crops in the farm. My husband told me, that I can only take my clothes’. Poor women in Kilosha explained ‘Women fall into poverty after they separate. They leave every belonging and asset with their husband.’ Because of their loss of assets upon separation, it is very difficult for most single women to start over and develop a sufficient asset base to provide adequately for themselves and their families. Respondents remarked, ‘Some women are household heads and have no men. You find that their husbands died, or they separated. They work hard to earn a living for their households, but they cannot do much to move their households ahead’ (Tanwa, low-income men). ‘There are women, who are poor, because their husbands or children, who used to provide for them, have died’ (Medu, low-income men).

6. Discussion

Following Butler (Citation1988), we hypothesised, that although gender is always being re-enacted and reproduced, spaces are continually emerging for women and men to renegotiate gender. Women and men perform gender endlessly, but they have the potential to use their agency to also challenge their own performances.

Our literature review indeed suggests that gender in Tanzania is in flux. To some extent the indigenous feminist movement has been successful, and progress has been achieved for instance in legislation. However, at the same time other elements appear to be pushing back, seeking to essentialise gender differences in ways that systemically afford women a weaker position. Gender equality legislation is not effectively implemented. The gender productivity gap is not addressed. Denying pregnant schoolgirls schooling means gender differentials in national capacity are likely to be reproduced inter-generationally.

Our fieldwork findings show a similar lack of cohesion. Men as much as women espouse support for gender equality. This may be associated with decades of indigenous activism, perhaps engagement by international development entities – as well as men’s and women’s personal beliefs. Even so, most (though not all) men respondents generally tend to associate the concept of gender equality with rather instrumental views on improving production, whereas women highlight reductions in gender-based violence and collaboration. However, the majority of men respondents place an interesting price on gender equality. This is that gender equality is contingent on men retaining primacy in decision-making, and that men control household income, including women’s income. In this, the term ‘joint’ may well mask an actual norm, that men take the final decision. Acosta et al. (Citation2019) report that in rural Uganda local understandings of joint decision-making includes situations where there is in fact no discussion at all. Women define jointness to include being informed by their husband that a decision has been made. Conceptions of jointness extend to discussions where the wife’s ideas are considered, but the man has the final say – there were no examples of women actually taking the final say (Acosta et al., Citation2019). It is possible that a wide range of understandings of jointness pertain also to the case study communities.

In contrast to men respondents in our study, women respondents argue for genuinely equal decision-making. There is a suggestion in some responses, though, that women are afraid to take decisions due to the threat of physical violence. As a reminder in relation to this, Bonatti et al. (Citation2019) consider that gender-based violence is a central element of how food and nutrition is organised in their study communities in Tanzania. They go further to suggest that violence against women is intrinsic to a society – like Tanzania – with segregated gender roles and a patriarchal, hierarchical social system. Male domination and consequent female subjugation, to use their language, can only be maintained in this way (Bonatti et al., Citation2019, p. 10). This reminds us of Morgenroth and Ryan (Citation2018) remarks on the importance of sanctions to a patriarchal system, which is trying to reproduce and sustain itself. In a study of Maasai women in Tanzania (Grabe, Dutt, & Dworkin, Citation2014), women considered that men’s ‘right’ to express violence against women was associated with men’s land ownership. When women own land, women are no longer men’s ‘property’ and therefore must be treated differently (Grabe et al., Citation2014). This indicates that violence may be considered not only as a sanction to induce conformity, but also a signifier of men’s ownership of women. In our study, this aspect was not researched, though study participants perceived rates of gender-based violence to be lessening as a consequence of broader normative change. Indeed, law enforcement agents are literally policing this. At the same time, it is clear that violence continues to some degree.

The question of equal decision-making is also tied to the control of assets. The findings show that the reality on the ground in our case study communities lies at a substantial distance to national legislation. Considering our data, it is hard to imagine that ‘legally, women may hold, own and dispose of property, and women have the same land rights as men. Laws provide for strong protections of women landowners, recognise a wife’s right to household land upon widowhood or divorce’ (Pedersen & Haule, Citation2013, p. 2). In the study communities, the majority of women – together with their children – become destitute, if their marriages fail or if their husbands die. In such a situation, women are left with little option but to construct themselves as feminine, submissive and docile. Thus, whilst married women may seek equality in decision-making, their generally very low control over – and ownership of – assets, means that they perform acts of submission in ostensible support of men’s decision-making. Maintaining their access to assets trumps attempts at decision-making autonomy. However, single women are freed from such a performance, and women respondents, who are financially secure, expressed a preference to be single in order to experience decision-making autonomy. These findings suggest performances of gender are differentiated by household typology.

Mbilinyi, cited above, said ‘the African woman thinks of herself as more than a wife and mother (Citation1972, p. 60). She is a cultivator, a weaver, a trader, and her occupational role is part of her self-image.’ Our findings show, that whilst women in the study communities may well think of themselves in those terms, men in the study communities find such a construction of women challenging. Local norms indicate that men are supposed to provide for their families, even though the reality is that in all locations women are engaged in on- and off-farm income generation. However, when women earn money locally, important performances of masculinities (man as breadwinner) and femininities (woman as housewife) are inevitably questioned. In this light, it seems very important to men, particularly, to create an image of women who work as ‘struggling’. Such language serves to relativise and diminish women’s contributions in relation to those of men. Couching women’s contributions as purely economic – and as under the control of men – allows men to retain dominance as decision-maker. In men’s remarks, there is no hint that women may actually want to earn money or to see themselves as breadwinners.

Brain (Citation1978) comments that women became homemakers during the colonial period. The literature review and our findings show, that the merging of women’s identity with homemaker is pervasive and thoroughly naturalised. It is here, that Butler’s concept of gender being performative has particular heft. At the same time, there are tantalising hints that men may be engaged in housework and childcare by simple virtue of women expressing this as a possibility. Admitting in public, though, that men carry out any form of housework is taboo. The fervent denials of this prospect, particularly by men – ‘It is abnormal … ’, ‘(It is) the opposite of what men are supposed to do’ suggest that associating men with the domestic sphere threatens their masculinity in a very deep way. Feinstein, Feinstein, and Sabrow (Citation2010) make very similar observations. They found that Tanzanian men express traditional expectations regarding gender roles, whilst women have more progressive expectations. Men generally felt that women should be responsible for children and do more work than men overall. Interestingly, their respondents suggested that disparities between women and men are natural, and they minimised the scale of any disparities (Feinstein et al., Citation2010)

Our findings show that understandings of gender are far from hegemonic. Women and men do engage, constantly, in gendered performances, and there is evidence that this behaviour is – at least to an extent – deliberative rather than a mere reflection of cultural norms. Women and men act to secure their personal well-being in the context of a limited range of cultural and economic options. Women in particular demonstrate ‘a differential consciousness, a new subject position that permits functioning within, yet beyond, the demands of dominant ideology’ (Sandoval, as cited in Grabe et al., Citation2014). Our fieldwork findings are redolent with remarks by women – and men – that speak to a much wider understanding of gender equality than is currently expressed in their daily lives. Butler (Citation1988) allows for agency in her model, simply because gender is an artifice – it is not real. Our study shows that women, and men, face very real limits to their personal agency. These limits are structural and as such pervasive. Even so, we came across tantalising evidence that, behind the scenes, a few married women and men may be acting gender in more gender equal ways. However, this cannot (yet) be expressed at community level. Maintaining a ‘gender norms façade’ appears critical (Galiè & Farnworth, Citation2019). Women and men must be seen as conforming to gender norms in public, but in private they may be doing something else altogether.

We have already noted the feminist transformative movement in Tanzania is developing indigenous analyses and strategies for promoting understandings of women as equal to men in all ways. A limitation of this study, which could be addressed in further research, is that we have not discussed the construction of masculinities, nor indigenous men’s movements for women’s equality. These include MenEngage Tanzania, which brings together 29 civil society organisations for women’s equality and positive masculinities (MenEngage Tanzania, Citationn.d.). Since gender is obviously relational, achieving a deeper understanding of how men perform gender in rural communities (beyond sexuality, which is well-researched) would be valuable. Broqua and Doquet (Citation2013), for instance, cite various studies to show that African men’s identities have undergone as much transformation as women’s have over the past century or so. They argue the history of masculinities is ‘directly marked by the colonial conquests, which altered their forms.’ This was achieved, they consider, through destabilising existing power systems, weakening the power of elders, and through subordinating black men to white men. Beyond this, they highlight the importance of working towards plural definitions of masculinity. ‘Men are not a single, uniform category, with inherently superior power. According to their properties and the geographical, ethnic, class, age, or other groups to which they belong, men’s relationships to gender norms and their positions in relation to women vary widely’ (Broqua & Doquet, Citation2013, p. 9). A large British study (Sweeting, Bhaskar, Benzeval, Popham, & Hunt, Citation2013) using longitudinal data, examined associations between gender role attitudes (GRAs), actual gender roles (marital status, household chore division, couple employment) and psychological distress in working-age men and women. They found that women, young people, and participants in less traditional relationships were less likely to express gender traditional attitudes. However, psychological distress (measured on a 12-point scale including items like feeling unable to perform normal activities and losing confidence in oneself) was higher among people – particularly men – with traditional GRAs. These findings have some clear parallels with our own study. It would be interesting to carry out a more detailed study bringing together the concept of performing gender with the psychological effects of attempting to maintain specific types of femininity and masculinity in similar rural settings in Tanzania.

7. Conclusion

In this paper we have provided a summary of the debates surrounding the relationship between progressive national policy and changing gender norms at local level in Tanzania. Our study complements this overview by adding further evidence to established findings and demonstrating how the continuous performance, reproduction and renegotiation of gender takes place as part of everyday lived experience in rural Tanzania as new livelihood opportunities challenge local normative understandings of what it means to be a woman or a man. We conclude that although national and local discourse embrace the idea of gender equality, practice is quite often different. Understanding how women and men seek to deploy their agency to create space for manoeuvre is an important aspect of recognising gendered performance and providing supportive measures

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on data collected as part of GENNOVATE case studies in Tanzania funded by the CGIAR Research Program on Maize. Development of research design and field methodology was supported by the CGIAR Gender & Agricultural Research Network, the World Bank, the governments of Mexico and Germany, and the CGIAR Research Programs on Wheat and Maize. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation supported the data analysis. We warmly thank the women and men farmers, who participated in this research and generously shared their time and views, as well as the members of the local data collection team and the data coding team. The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and not of any organization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The full methodology is available at www.gennovate.org.

References

- Acosta, M., Ampaire, E., Okolo, W., Twyman, J., & Jassogne, L. (2016). Climate change adaptation in agriculture and natural resource management in Tanzania: A gender policy review (CCAFS Info Note). Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/132686849.pdf

- Acosta, M., van Wessel, M., van Bommel, S., Ampaire, E. L., Twyman, J., Jassogne, L., & Feindt, P. H. (2019). What does it mean to make a ‘joint’ decision? Unpacking intra-household decision making in agriculture: Implications for policy and practice. Journal of Development Studies, 1–20. doi:10.1080/00220388.2019.1650169

- Badstue, L., Petesch, P., Feldman, S., Prain, G., Elias, M., & Kantor, P. (2018). Qualitative, comparative, and collaborative research at large scale: An introduction to GENNOVATE. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3(1), 1–27.

- Bonatti, M., Borba, J., Schlindwein, I., Rybak, C., & Sieber, S. (2019). ‘They came home over-empowered’: Identifying masculinities and femininities in food insecurity situations in Tanzania. Sustainability, 11(15), 1–15.

- Brain, J. L. (1978). Down to gentility: Women in Tanzania. Sex Roles, 4(5), 695–715.

- Broqua, C., & Doquet, A. (2013). Considering masculinity in Africa and beyond. Cahiers d’Études Africaines, 2013/1(209–210), 9–41.

- Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519–531.

- Croll, E. J. (1981). Women in rural production and reproduction in the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, and Tanzania: Socialist development experiences. Signs, 7(2), 361–374.

- Daley, E. (2005a). Land and social change in a Tanzanian village 1: Kinyanambo, 1920s-1990. Journal of Agrarian Change, 5(3), 363–404.

- Daley, E. (2005b). Land and social change in a Tanzanian village 2: Kinyanambo in the 1990s. Journal of Agrarian Change, 5(4), 526–572.

- Dancer, H. (2015). Women, land and justice in Tanzania. Eastern Africa Series. Woodbridge: James Currey.

- Dancer, H., & Sulle, E. (2015). Gender implications of agricultural commercialisation: The case of sugarcane production in Kilombero District, Tanzania (Future Agricultures Working Paper No. 118). Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

- Ellis, A., Blackden, M., Cutura, J., MacCulloch, F., & Seebens, H. (2007). Gender and economic growth in Tanzania: Creating opportunities for women. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ewans School of Public Affairs. (2011). Gender and agriculture in Tanzania (EPAR Brief No. 134). Seattle, WA: Leavens, M.K. & Anderson, C. L.

- Farnworth, C. R. (2007). Achieving respondent-led research in Madagascar. Gender & Development, 15(2), 271–285.

- Feinstein, S., Feinstein, R., & Sabrow, S. (2010). Gender inequality in the division of household labour in Tanzania. African Sociological Review, 14(2), 98–109.

- Feldman, S. (2018). Feminist science and epistemologies: Key issues central to GENNOVATE’s research program. GENNOVATE resources for scientists and research teams. CDMX, Mexico: CIMMYT.

- Fortmann, L. (1982). Women’s work in a communal setting: The Tanzanian policy of Ujamaa. In E. G. Bay (Ed.), Women and work in Africa (pp. 191–205). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Galiè, A., & Farnworth, C. R. (2019). Power through: A new concept in the empowerment discourse. Global Food Security, 21, 13–17.

- Geiger, S. (1996). Tanganyikan nationalism as ‘women’s work’: Life histories, collective biography and changing historiography. The Journal of African History, 37(3), 465–478.

- Grabe, S., Dutt, A., & Dworkin, S. (2014). Women’s community mobilization and well- being: Local resistance to gendered social inequities in Nicaragua and Tanzania. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(4), 379–397.

- Human Rights Watch. (2019). World report 2019: Tanzania and Zanzibar country chapters. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/tanzania-and-zanzibar

- Jones, J. (2018, February 7). Theorist Judith Butler explains how behavior creates gender: A short introduction to ‘gender performativity’. Retrieved from http://www.openculture.com/2018/02/judith-butler-on-gender-performativity.html

- Kinunda, N. (2017). Negotiating women’s labour: Women farmers, state, and society in the southern highlands of Tanzania (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Göttingen.

- Lal, P. (2010). Militants, mothers, and the national family: Ujamaa, gender, and rural development in postcolonial Tanzania. Journal of African History, 51(1), 1–20.

- Lange, S. (1995). From nation building to popular culture: Modernization of performance in Tanzania. Bergen, Norway: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Mbilinyi, M. (2016). Analysing the history of agrarian struggles in Tanzania from a feminist perspective. Review of African Political Economy, 43(sup1), 115–129.

- Mbilinyi, M. J. (1972). The ‘new woman’ and traditional norms in Tanzania. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 10(1), 57–72.

- MenEngage Tanzania. (n.d.). Menengage Tanzania. Retrieved from Retrieved from http://menengage.org/regions/africa/tanzania/

- Meyerhoff, M. (2015). Gender performativity. In P. Whelehan & A. Bolin (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of human sexuality (pp. 456–459). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ministry of Finance and Planning. (2016). National five-year development plan 2016/17-2020/21. Retrieved from http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/tan166449.pdf

- Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. (2016). Tanzania country gender profile. Retrieved from https://data.em2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/TZ-Country-Gender-Profile-004.pdf

- Morgenroth, T., & Ryan, M. K. (2018). Gender trouble in social psychology: How can Butler’s work inform experimental social psychologists’ conceptualization of gender? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–9.

- Pedersen, R. H., & Haule, S. (2013). Women, donors and land administration: The Tanzania case (DIIS Working Paper No. 19). Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS.

- Petesch, P., Badstue, L., Camfield, L., Feldman, S., Prain, G., & Kantor, P. (2018). Qualitative, comparative and collaborative research at large scale: The GENNOVATE field methodology. Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security, 3(1), 28–53.

- Schlindwein, I. L., Bonatti, M., Bundala, N. H., Naser, K., Löhr, K., Hoffmann, H. K., … Rybak, C. (2020). Perceptions of time-use in rural Tanzanian villages: Working with gender-sensitive tools in nutritional education meetings. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 7.

- Sutz, P., Seigneret, A., Richard, M., Blankson, A. P., Alhassan, F., & Fall, M. (2019). A stronger voice for women in local land governance: Effective approaches in Tanzania, Ghana and Senegal. London, UK: International Institute for Environment and Development, IIED.

- Sweeting, H., Bhaskar, A., Benzeval, M., Popham, F., & Hunt, K. (2013). Changing gender roles and attitudes and their implications for well-being around the new millennium. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(5), 791–809.

- TGNP Mtandao. (2018, August 28). Vision 2025: Embracing strategic gender needs in agricultural sector. Retrieved from https://tgnp.org/2018/08/28/vision-2025-embracing-strategic-gender-needs-in-agricultural-sector/

- USAID. (2018). Tanzania gender and youth fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.usaid.gov/documents/1860/tanzania-2016-gender-and-youth-fact-sheet

- World Bank. (2015). The cost of the gender gap in agricultural productivity in Malawi, Tanzania, and Uganda (English). Author. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/847131467987832287/The-cost-of-the-gender-gap-in-agricultural-productivity-in-Malawi-Tanzania-and-Uganda

- World Economic Forum. (2006). The global gender gap report 2006. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2006

- World Economic Forum. (2019). The global gender gap report 2018. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2018