?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Using two waves (2013, 2015) of the Micro, Small, and Medium sized Enterprises (MSMEs) survey of Vietnamese manufacturing firms, this paper first explores what drives firms’ decision to have a domestic standards certificate, taking into account a rich number of factors related to the cost and expected benefits of certification as well as institutional factors. It further explores the presence of a positive and significant effect of domestic certificates on firm growth, testing whether these serve as signalling devices for desirable attributes under information asymmetry. Evidence is indeed found for a signalling effect of domestic standards certification, being stronger for female-run businesses. Results hold even when controlling for international certifications.

1. Introduction

A better understanding of the mechanisms of growth of entrepreneurial firms is nowadays of great relevance for academics and policy-makers alike. A vast empirical literature explores the factors affecting entrepreneurship and growth, both in advanced and developing economies. The industrial economics literature generally points at firm size and age as main determinants of growth (Evans, Citation1987a, Citation1987b), as firms discover their efficiency levels over time in competition with the market and adjust their size accordingly (Jovanovic, Citation1982; Sutton, Citation1997). Models of active learning emphasise the role played by learning- and innovation-related variables in raising efficiency levels (Pakes & Ericson, Citation1998), enabling firms to experience additional growth opportunities (Audretsch, Coad, & Segarra, Citation2014; Doms, Dunne, & Roberts, Citation1995). In developing countries, however, these market selection mechanisms are severely hampered by market and systemic failures related to asymmetric information, high transaction costs, and weak institutions, explaining why in developing countries firms fail to grow into a larger size (Goedhuys & Sleuwaegen, Citation2010; Roberts & Tybout, Citation1996; Tybout, Citation2000).

In response to the higher transaction costs and information asymmetries, firms can try to signal their quality and gain the reputation and legitimacy needed to access more markets and resources, and ultimately to grow (Sleuwaegen & Goedhuys, Citation2002). Empirical evidence shows that adherence to standard certificates can indeed serve such a purpose: acting as a signalling device, certificates can facilitate the access to broader, international, and higher-end markets. This is of great importance for firms in developing countries. Since consumers tend to infer the quality of the seller from the general reputation of the country of origin, these firms suffer from reputation problems more than firms in advanced economies, facing greater difficulties in credibly signalling their quality (Hudson & Jones, Citation2003). In this way, certificates may serve as policy instruments to support the participation of actors from less developed economies in global trade.

The relevant literature focuses almost exclusively on the analysis of international management standard certificates (such as ISO 9001 for quality management and the ISO 14001 for environmental management), while leaving the features, determinants, and implications of domestic certificates largely underinvestigated. With the majority of firms in many developing countries being small and serving mainly domestic and local markets, as well as often being too resource constrained to meet the requirements of international certificates, the question arises whether complying with a domestic standard certificate could play a comparable role for these firms’ performance. Can a domestic certificate act as a signalling device to improve firms’ reputation, easing the lemon problem of information asymmetries between firms and their clients, and ultimately fostering firm growth?

This paper addresses this question and empirically analyses the mechanisms relating domestic certificates to firm growth using the 2015 and 2013 waves of the Micro, Small, and Medium sized Enterprises (MSMEs) survey of Vietnamese manufacturing firms. The MSMEs survey offers unique information about two families of domestic certificates: national environmental standard certificates (ESCs) and domestic quality certificates (QCs), the latter referring to various quality certificates recognised only in Viet Nam. Since both types of certificates are awarded by national organisations and agencies, and are recognised only within the country, we classify them as domestic certificates. For firm level performance, we investigate firms’ sales growth, using empirical specifications from the industrial economics literature studying firm dynamics and explaining firm size distributions in developed and developing countries (Evans, Citation1987a, Citation1987b; Sleuwaegen & Goedhuys, Citation2002; Sutton, Citation1997). This focus on sales growth and on domestically awarded certificates represents a novelty within the body of empirical literature on SMEs performance in Viet Nam, since empirical studies have, instead, looked at the effects of international certifications on other performance indicators, such as labour productivity (Calza, Goedhuys, & Trifković, Citation2019; Trifković, Citation2016), business risk (Trifković, Citation2018), work conditions (Trifković, Citation2017), and environmental performance (Nguyen & Hens, Citation2015).

The proposed analysis is of particular relevance for Viet Nam. Even if between 2005 and 2015 small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the manufacturing sector experienced an exponential growth in terms of number of firms and employed workforce, which accounts for about half of the manufacturing labour force (Phan, Nguyen, Mai, & Le, Citation2015), Vietnamese entrepreneurial firms follow the pattern observed in many developing countries and tend to stagnate around small sizes (CIEM, DoE, ILSSA, & UNU-WIDER, Citation2016). The sluggish growth of entrepreneurial firms has become of great concern and policy relevance in Viet Nam, as proved by the approval of the Law on Support for Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises in early June 2017.

We simultaneously estimate the equations for the probability of having a domestic certificate and for sales growth as a recursive mixed-process model. We find evidence of a positive correlation between domestic certificate and firm growth. This result holds even when international certifications are controlled for, providing evidence that domestically awarded certificates support entrepreneurial growth. Thus, our empirical findings suggest that domestic certifications may serve entrepreneurial policy purposes by alleviating sluggish entrepreneurial growth.

The empirical analysis follows the work of Terlaak and King (Citation2006) in trying to disentangle the external signalling effect on sales growth from internal operational improvements driven by the certification process. Since the positive relationship between domestic certificates and sales growth persists even once operational and environmental improvements are controlled for, this result provides evidence of an external signalling effect that reduces information asymmetries. In addition, our analysis is original in exploring this signalling effect through a gender perspective, acknowledging that attitudes and gender stereotypes may pose additional transaction costs on female-run businesses. Finally, the presented study offers new insights to the debate on what drives firms’ decision to have a domestically recognised certificate. The results confirm that, besides firm-level characteristics such as size and age, factors related to institutional pressure affect the probability of having a domestic certificate.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the relevant empirical literature on the effects and determinants of standard certificates among firms in developing countries. Section 3 briefly describes the data used. The model, the estimation strategy, and the description of the variables used are presented in Section 4. Section 5 comments on the results of the empirical analysis and includes several robustness checks. Results are discussed in Section 6, followed by Section 7 that concludes.

2. Literature and hypotheses development

This section presents a review of the literature on the determinants and effects of certification on firms operating in a developing context. Although most of this literature deals with the family of international management standard certificates (such as ISO 14001 and ISO 9001), the micro-level mechanisms underlying the adoption and implications of these certificates are likely to hold for domestic ones too. Focusing on those contributions that are applicable to domestic certificates, this section sets the background for the hypotheses tested in the empirical analysis.

2.1. The advantages of certification

One of the main benefits of having a certificate is the reduction of transaction costs achieved by revealing quality and increasing a firm’s legitimacy and reputation to external parties (Holleran, Bredahl, & Zaibet, Citation1999; King, Lenox, & Terlaak, Citation2005; Potoski & Prakash, Citation2005). Certification contributes to reducing information asymmetry by communicating non-market information about process and product characteristics in market transactions (for example quality, safety, environment, work conditions), thus serving ‘as signal of superior but unobservable attributes and thus provide a competitive benefit’ (Terlaak & King, Citation2006, p. 580).

Certified firms can therefore engage more easily in transactions and enjoy larger sales. The increase in sales can be driven either by an increase in the quantity sold or – if firms are not price-takers – by higher prices due to the higher willingness to pay of consumers, this representing a pure certification premium (Henson, Masakure, & Cranfield, Citation2011). Standards certificates can also contribute to reducing variability in firm revenues and business risk, when these are associated with a scarce customers’ ability to assess products quality and safety (Trifković, Citation2018). The literature refers to this positive direct impact of standard certificates on revenues from sales and/or export as an external effect originating from a better competitive position in the market (Clougherty & Grajek, Citation2014).

The magnitude of this external effect may vary with market conditions and firm characteristics. In economies where transaction costs are particularly high, the advantages of having a certificate acting as signalling device are potentially larger. This is the case in emerging and developing economies, where markets are typically characterised by lower efficiency, weaker selection, and higher information asymmetries (Goedhuys & Sleuwaegen, Citation2013; Henson & Jaffee, Citation2006; Henson et al., Citation2011; Masakure, Henson, & Cranfield, Citation2009).

Also, certain firm-level features may concur to exacerbate reputation issues as a consequence of imperfect information. For example, the study of female entrepreneurship shows how the presence of gender-based stereotypes in developing countries often leads to a differential treatment for female entrepreneurs in terms of access to markets (Kantor, Citation2005), to land and productive resources (UN Women & OHCHR, Citation2013), and to financial assets (Pham & Talavera, Citation2018). The origin of this discrimination is associated with the predominance of traditional gender roles, which leads to what Elam and Terjesen (Citation2010) define as ‘gendered cultural institutions’. When a trait that is typically considered as masculine such as leadership is displayed by women, it gives rise to a ‘role incongruity’ (Sharma & Tarp, Citation2018) that generates the perception of women in leadership roles as less qualified than men with similar characteristics. This makes it more difficult for women to have the quality of their management recognised, resulting in higher barriers, transaction costs, and discrimination. Besides empirically investigating the presence of a positive external signalling effect, the proposed analysis also tests the hypothesis that domestic certificates represent an institutional response to gender-led constraints, providing larger benefits to female-run enterprises.

In addition to the external effect, certificates can foster learning and capability development in certified firms, as they also represent a form of codified knowledge about superior practices (Calza et al., Citation2019; Zoo, de Vries, & Lee, Citation2017). Implementing standard certificates often goes hand in hand with improvements in internal operations, organisation, management, and environmental conditions, in line with what is required to acquire the certificate (Delmas & Pekovic, Citation2013). These operational improvements can raise firm’s efficiency and productivity, ultimately translating into additional growth opportunities. A number of recent empirical studies indeed find evidence of this positive internal effect even among firms in developing and emerging countries (Calza et al., Citation2019; Gallego & Gutiérrez, Citation2017; Goedhuys & Mohnen, Citation2017; Trifković, Citation2017). Given their potential impact on sales growth, this internal effect also has to be taken into account when empirically investigating the external signalling effect of domestic certificates. For this reason, the proposed analysis looks for evidence of a pure signalling effect of domestic certificates by controlling for operational improvements.

2.2. The determinants of certification

The decision to adopt and maintain a certificate has typically been modelled as a function of expected benefits and costs: firms become certified if they believe that the benefits would exceed the costs of successfully obtaining and maintaining a certificate.

Looking at benefits, reducing information asymmetry is one of the main expected advantages of having a certificate: the larger the information gap, the larger the potential benefits from its reduction, the more likely a firm is to find it strategic to become certified (King et al., Citation2005). This can be the case in industries where capabilities and quality are hard to observe, such as in technology-intensive sectors (Terlaak & King, Citation2006), or when parties are physically, culturally, and linguistically distant, as in the case of firms engaging in international trade through export or participation into global value chains (Potoski & Prakash, Citation2009).

Since the early 2000s a growing literature has emphasised the role of institutional pressure in affecting the certification decision. According to the new institutional theory, actors can obtain legitimacy by explicitly conforming to some practices that are perceived as necessary or as state-of-the-art among their peers. The non-compliance with these practices implies a loss of reputation, even leading to exclusion from the market (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). This institutional pressure can take three different forms: coercive, normative, and mimetic (Scott, Citation1995). While normative pressure is associated with sector-level practices that are perceived as the appropriate way to do things among peers, coercive pressure originates from the fear of repercussions from a higher power, this eventually being an international partner (for example, foreign firms operating within the same value chain), the government, or costumers, activist associations, and trade unions (Fikru, Citation2014). Mimetic pressure comes from looking at and imitating competitors, peers, or other actors perceived as desirable models. As shown by Delmas and Montiel (Citation2008) and Liu et al. (Citation2010), firms tend to imitate competitors in their corporate and environmental managerial practices. Therefore, we also test the effect of various forms of institutional pressure on having a domestic certificate.

The cost of getting and maintaining a certificate is another force likely to affect the certification decision. This includes both the direct costs, such as the fees associated with the administrative procedures (Masakure, Cranfield, & Henson, Citation2011), and the indirect costs of compliance with the certification requirements, such as the time and resources spent in generating the necessary documentation and in implementing changes, such as workforce training and improving workplace conditions (Goedhuys & Mohnen, Citation2017). The literature is quite unanimous in recognising that for small firms both direct and compliance costs may represent a serious obstacle to certification, while larger firms are more likely to enjoy resources and economies of scale to spread the costs of adoption (Hudson & Orviska, Citation2013) as well as broader networks, which help them recognise the benefits of a certificate (Fikru, Citation2014). Certification costs may turn out to be non-trivial and cumbersome for firms operating in a developing country (Maskus, Otsuki, & Wilson, Citation2005, Citation2013), where these are typically smaller and more resource-constrained, and tend to lag behind in terms of capabilities. This implies that certification requirements can pose relevant challenges to firms operating with a lower stock of knowledge and far away from organisational best practices, making the certification process relatively more costly and, consequently, less likely.

In sum, the lemons problem is rife, worse in developing countries due to a lack of established players, as many industries are fragmented with a large number of small firms. In such a setting, markets can get stuck in a bad equilibrium: small firm size constrains firms’ ability to obtain costly international certifications, and lack of certification in turn constrains firm growth. Can domestic certifications help to alleviate the information problem and facilitate firm growth? We address this question in the following empirical analysis.

3. Data

The data used in the present study come from the 2013 and 2015 rounds of the Small and Medium Scale Manufacturing Enterprise (MSMEs) surveyFootnote1 conducted every second year between 2005 and 2015 to assess the characteristics of the Vietnamese business environment. The survey targets firms active in manufacturing sectors with fewer than 300 employees, covering 10 provinces (Ho Chi Minh City [HCMC], Hanoi, Hai Phong, Long An, Ha Tay, Quang Nam, Phu Tho, Nghe An, Khanh Hoa, and Lam Dong). The first 2005 survey was representative at province level and the random sample was stratified by ownership type to include: household establishments, private enterprises, collectives or cooperatives, and limited liability and joint stock companies.

Besides providing rich data on enterprise characteristics, the Vietnamese MSMEs survey offers unique information on two families of certificates recognised only in Viet Nam: the domestic Quality Certificates (QC) and the national Environmental Standard Certificates (ESC). The QCs are regulated by the Law on Standards and Technical Regulations (2007), which has been in place following the country’s accession to the WTO in 2007. This legislation distinguishes between technical regulations and national standards. Technical regulations set mandatory requirements (for example, the percentage of fat allowed in pasteurised milk) and tend to be industry-specific, their development and compliance being direct responsibility of line ministries. National standards, instead, are adopted on a voluntary basis and define general technical standards for product conformity and quality, these being industry-specific (for instance, food safety certificates) or applicable to different sectors and activities (for example, the TCVN, which translates as ‘quality certificate of Vietnamese standard’). The Ministry of Science and Technology is the responsible agency for preparing, issuing, and managing the domestic quality certificates through its Directorate for Standards, Metrology and Quality of Vietnam (STAMEQ).Footnote2

The national environmental standard certificates (ESCs) are regulated by the 2005 Law on Environmental Protection (LEP), the Decree 29/2011 and the circular 2781/TT-KCM (CIEM, DoE, ILSSA, & UNU-WIDER, Citation2016). All firms are encouraged to and can obtain an ESC. The enterprise that wants to be granted an ESC from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment has to prove compliance with the implementation of the pollution and environmental control initiatives it committed to in an environmental impact assessment (EIA). The Decree 29/2011 of the LEP requires firms performing some specific polluting and environmentally hazardous activities to conduct a detailed EIA and to have it approved, after which firms can opt to have their environmental performance certified to obtain the ESC. In addition, the Circular 2781/TT-KCM requires firms in some industries (for example, leather) to also obtain an ESC – these firms being the only ones for which an ESC is actually required. However, despite these legislative efforts, evidence suggests that ESCs have had scarce success in Viet Nam (Ho, Citation2016): their diffusion is in practice still very limited due to the low level of compliance, which may be due to a generalised scarce knowledge about the environmental regulations and to a lack of enforcement. The lack of enforcement makes de facto the ESC comparable to voluntary certificates when it comes to its potential as a signalling device.

The MSMEs survey collects information on the ESC since 2011, but the question about domestic quality certificates (QCs) was added only in the 2015 wave. The 2015 survey wave provides additional interesting information about the QC, such as its direct costs and the specific type of quality certificate obtained. This information is unique and rarely available in a developing context. Thus, for the proposed analysis we consider manufacturing firms that participated in both 2013 and 2015 survey waves.Footnote3 With the main purpose of analysing the effect of domestic certificates on firms serving the domestic and local market, we focus on domestic sales and remove exporting firms from the sample. In fact, firms selling in foreign markets tend to face different competitive regimes, where domestic certificates are not likely to have a signalling impact. After removing observations with missing values, we remain with a balanced sample of 1,877 manufacturing enterprises that participated in both 2013 and 2015 survey waves.

reports the distribution of Vietnamese firms with certificates in the considered sample in 2015. We define as domestically certified any firm that declares to have at least one of the two types of certificates (QC or ESC) in 2015. Around 22 per cent of firms have at least one domestic certificate. This is a relatively large share when compared to the share of firms with an international standard certificate (such as ISO 9001 and/or ISO 14001), which do not reach 3 per cent of the considered sample. also shows how most businesses that have obtained an international certificate tend to also have a domestic one. presents the composition of domestic and international certificates by sector and province in 2015.

Table 1. Number and proportion of firms with a domestic and/or an international certificate (2015)

Table 2. Number and proportion of firms with a domestic and/or an international certificate by province and sector (2015)

4. Empirical approach

4.1. Empirical model and variables

We start by modelling the probability of a firm having a domestic certificate in 2015 with a probit equation, assuming the following relationship:

where is the latent variable underlying the dichotomous response of having a domestic certificate, which depends on the vector of explanatory variables

. The error term

is assumed to be normally distributed (

). We only observe the binary outcome as:

where the dependent variable is a variables which takes the value 1 if the firm has a domestic certificate (either a QC or ESC or both) in 2015 (and 0 otherwise). Following the literature review presented in Section 2, we introduce

, a vector of explanatory variables that are likely to influence the probability of having a domestic certificate. The explanatory variables can be divided into three categories.

A first group of explanatory variables () includes factors accounting for higher transaction costs. Since information asymmetry is likely to increase with larger physical and cultural distance between actors, we introduce a variable accounting for the distance from the main customer (Distance) as well as sector dummies (at 2-digit), these accounting for intra-industry differences in terms of technological complexity and practices that may exacerbate transaction costs.

The second group () contains proxies for the three types of institutional pressure. Coercive pressure from customers and workers is accounted for with the variables Certification required by customersFootnote4 and Local trade union, respectively. We also introduce the variable Inspection to account for the coercive pressure from authorities and regulations, arguing that this variable can serve as proxy for the burden of red tape (Fikru, Citation2014). Since provinces enjoy a certain autonomy in the implementation of policies and regulations, location controls are also added. Normative pressure is taken into account with a variable measuring the knowledge of the labour code (Labour code) and a dummy for being part of a business association (Business association). For mimetic pressure we consider factors that facilitate access to information on domestic certificates as well as the possibility to imitate peers’ behaviour: a dummy for having access to an Internet connection (Internet) (Fikru, Citation2014) and the share of firms having a domestic certificate within the same district (Neighbour certificates), the latter accounting for a network effect in the diffusion of relevant information and practices (Hansen & Trifković, Citation2014).

The third group () includes factors related to direct and indirect costs of certification. Since firms owning a domestic quality certification (QC) are asked to report its cost, we can generate a proxy of the average direct costs of a domestic QC (Cost of domestic quality certificate).Footnote5 These entail costs related to registration fees, administrative requirements, and internal audit. To control for firm’s ability to bear the indirect costs of complying with the certification process, we include firm size (measured as number of employees), age, and type of ownership.

The main interest of this analysis lies in exploring the link between domestic certificates and firm growth. We follow the tradition of the industrial economics literature and model the growth of firms as a function of firm size and firm age, to account for the empirical stylised facts that young and small firms tend to grow faster than older and larger businesses (Coad, Citation2009), as predicted by models of active and passive learning (Jovanovic, Citation1982; Pakes & Ericson, Citation1998). The basic empirical model is thus a general growth function as proposed by Evans (Citation1987a, Citation1987b) and used by Sleuwaegen and Goedhuys (Citation2002), Yasuda (Citation2005), and Park, Shin, and Kim (Citation2010):

where and

are the size of firm

at the end-of-period

(2015) and at the beginning-of-period

(2013), respectively. Firm age (

), is expressed as the years in operation in time

. In line with the arguments developed in Section 2, this functional relationship is moderated through a set of firm specific variables (

), which are supposed to interact with the basic function in the following exponential way:

Approximating EquationEquation (4)(4)

(4) with a second order logarithmic expansion of a generalised function relating firm growth to size and age, the estimating growth equation becomes:

The set of firm specific variables includes the main independent variable, Domestic certificate (

). To test whether the effect of having a domestic certificate is driven only by the market reaction to certification (external effect), we control for operational improvements by including factors related to firm’s internal organisational and environmental practices (

): a set of dummy variables (Fire, Air, Waste, Other) that take the value one if the firm reports to have implemented environmental improvement procedures (irrespective of whether it has certified for it) and a dummy variable that takes the value of one if the firm provide training to workers (Training). This approach is similar to that proposed by Terlaak and King (Citation2006), who use a measure of scrap generation to approximate the improvement in operational performance. Finally, the presence of technology-related variables such as Innovation (

) is in line with the active learning models of Ericson and Pakes (Citation1995). Sector and location (province) dummies are also included. We now rewrite the estimating annual sales growth equation as:

We further refine our analysis by implementing two alternative specifications for EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) . First, we test whether a female entrepreneur or owner, who is more likely to face higher transaction costs (see Section 2), may benefit more from the signalling effect of having a domestic certificate. To do that we introduce an interaction term between the independent variable

and a dummy that takes the value of 1 if the firm is headed by a woman (Female). Second, we verify whether the effect of having a domestic certificate could be driven by the presence of an international certificate (such as ISO 9001 or 14001). In fact, international certificates can also signal premium quality to domestic customers and positively affect sales growth. Since in the considered sample many firms with an international certificate also have a domestic one (see ), we create an ordered categorical variable Certification (

), whose categories take the values: 1 if the firm does not have any certification, 2 if the firm has only a domestic certificate, and 3 if the firm has an international certificate, alone or in combination with a domestic certificate. We then modify EquationEquation (6)

(6)

(6) as follows:

where is used as base category. The comparison of the coefficients

and

would reveal whether having an international certificate may have a stronger signalling effect on domestic sales growth.

presents the definition and summary statistics of all variables employed in the empirical analysis.

Table 3. Variables definitions and summary statistics

4.2. Estimation strategy

The empirical analysis of the effects of domestic certificates on sales growth poses a series of methodological issues. Since certificates are not randomly assigned, the main concern arises from selection. Moreover, if selection into domestic certification is driven by faster growth, reverse causality may also be present.

To obtain unbiased and consistent parameters, we simultaneously estimate the equations for sales growth and for the probability of having a domestic certificate as a recursive mixed-process model.Footnote6 This approach addresses the endogeneity of the independent variable in the sales growth equation under the condition that the model is correctly specified, meaning that one (or more) of the covariates in the certification equation fulfils the exclusion restrictions – that is, it significantly affects the endogenous variable (

) but not the outcome variable (

). We identify three variables that fulfill the exclusion restrictions: Cost of domestic quality certificate, Trade union, and Certification required by costumers. As discussed in Section 4.1, all these variables are likely to shape the adoption decision, while a direct link with sales growth is not clearly established. The results of the conventional tests for instruments validity confirm that these variables serve as valid instruments for identification.Footnote7 To account for the role of international certifications we apply the same methodology and simultaneously estimate the equations for sales growth and an ordered probit model for the categorical variable Certificate.

The proposed estimation strategy is effective in dealing with endogeneity due to selection on observables but cannot account for bias due to unobservables. This issue could be solved with the application of panel data techniques. However, since the information on domestic quality certificates (QCs) is available only in 2015, we cannot take advantage of the panel structure of the MSMEs survey and have to constrain our empirical analysis to a cross-section environment. We can still try to control as much as the data allow for individual heterogeneity by accounting for a large number of observable factors and including lagged variables. Still, the impossibility to fully control for individual effects and pre-certification trends does not allow us to claim for causality when interpreting the obtained results.

We also conduct several robustness checks. First, we run the main models over different samples and subsamples, including exporting firms and splitting the sample by type of ownership. Second, we implement propensity score matching (PSM) techniques to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATET) when the selection into the treatment is not random. In our case the treatment corresponds to having a domestic certificate, while sales growth is the outcome variable upon which the treatment’s effect is assessed.

5. Results

5.1. The determinants of domestic certification

displays the results of the probit model for domestic certification. Column (1) presents the results of an individual probit model and column (2) shows the results of the simultaneous estimation of the probit with the sales growth equation. Our findings reveal a significant correlation between adoption decision and the sets of factors related to larger information asymmetries, higher costs of certification, and stronger institutional pressure.

Table 4. Determinants of domestic certification: marginal effects

First, transaction costs have a positive effect on adoption: the coefficient of distance from customers is positive and significant (even if only at 10% in the individual probit model), implying that doubling the average distance increases the likelihood of having a domestic certificate by about 10 percentage points, all else being equal. This provides evidence that when customers are physically distant and the collection and exchange of information becomes more challenging, firms are indeed more likely to become certified.

Second, all factors accounting for different types of institutional pressure are found to significantly influence certificate adoption. Firms experiencing coercive pressure from workers (Local trade union), costumers (Certification required by customers), and authorities and regulations (Inspected) have a higher probability of having a domestic certificate of about 6, 30 and 6 percentage points, respectively. Being a member of a business association also raises by 6 percentage points the probability of having a domestic certificate, while a good knowledge of the labour code raises the same probability by 3 or 4 percentage points depending on the model (only the coefficient in column (2) is significant). Mimetic pressure also seems to affect certification decisions: having an Internet connection is associated with an increase of more than 9 percentage points in the probability of having a domestic certificate, and there is evidence of a positive network effect. All these results emphasise the importance of institutional pressure in shaping adoption decisions: this suggests that Vietnamese firms are becoming more and more aware of the importance of quality and environmental performance for customers, and thus behave more proactively and responsibly by becoming certified. The large effect of the variable Certification required by customers is fully in line with this argument.

Third, as expected, the cost of getting the certificate impacts negatively and significantly the likelihood of being certified: a doubling in the direct cost induces a decrease of almost 3 percentage points in the probability of having a domestic certificate, all else being equal. This effect is of the same sign but of smaller magnitude than what was found by Masakure et al. (Citation2011) in the case of international standard certificates. Similar to what was found by Gebreeyesus (Citation2015) in Ethiopia, larger and older firms are more likely to have a domestic certificate: a doubling in firm employment, from the average of 13 to 26 employees, increases the probability of having a domestic certificate by approximately 6 percentage points, while doubling the number of years in activity rises this probability by approximately 3 percentage points. These findings suggest that the barriers to adopting and maintaining a certificate are not exclusively of a financial nature: besides having more resources, large and older firms have accumlated more capabilities, knowledge, and networks over time, all these contributing to reducing compliance costs of certification (Fikru, Citation2014).

5.2. The effect of domestic certificates on sales growth

presents the results of the sales growth equation. Columns (1) and (4) report the OLS results (with robust standard errors) as reference. Our comments focus on the results obtained with the simultaneous estimation presented in columns (2), (3), and (5), which are estimated to adresss endogeneity.

Table 5. Sales growth: main drivers

Column (2) presents the results for the model in EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) . With the introduction of several variables to control for operational and environmental improvements and other efficiency-enhancing factors, we can interpret the coefficient of domestic certificate as capturing the net signalling premium from costumers’ and markets’ reaction to certification: having a domestic certificate is correlated with a 22 per cent increase in sales growth. This effect is close to what Goedhuys and Sleuwaegen (Citation2013) found for international certification once productivity gains had been accounted for (around 20%). The fact that the coefficient of Domestic certificate becomes larger when dealing with endogeneity suggests a downward bias, possibly due to omitted variables affecting growth and certification in opposite directions. This may be the case if firms with decreasing sales try to reignite their performance by becoming certified (Trifković, Citation2017).

Column (3) presents the results of the specification when we interact the variable Domestic certificate with the dummy variable Female to test whether the signalling effect is stronger for female run businesses. The coefficient of this interaction term is positive and significant, this suggesting that female-run enterprises may gain significantly larger benefits from being domestically certified. We interpret this result as evidence of female entrepreneurs’ difficulty of raising trust about their managerial and business qualities, supporting the hypothesis that a domestic certificate may enable them to overcome this gender bias and increase their reputation. This is consistent with the findings of other studies investigating the role of certifications in alleviating gender discrimination and fostering women’s empowerment in developing countries (Melesse, Dabissa, & Bulte, Citation2018). This result also shows that gender stereotypes may still be constraining women’s empowerment in business in Viet Nam, as suggested by World Bank (Citation2017).

Column (5) displays the results of the simultaneous estimation of the sales growth equation with an ordered probit for the variable Certification () (as in EquationEquation (7)

(7)

(7) ). Having only a domestic certificate is still associated with a positive signalling premium, corresponding to a 20 per cent increase in sales growth. In line with the empirical literature on international certificates, we also find evidence of a significant and positive growth bonus for internationally certified firms, suggesting a 33 per cent increase in annual average sales growth. This result suggests that international certificates can serve as signalling devices also for domestic customers, their larger effect confirming the hypothesis that a stronger signalling effect is retrieved from a more demanding certification.

In line with the existing empirical literature, all models present a positive and significant effect on sales growth of having an Internet connection (Internet) and having introduced a product or process innovation (Innovation). We also find evidence that smaller firms experience larger sales growth, on average and controlling for other firm characteristics.

5.3. Robustness checks

5.3.1. Different samples

We perform various additional estimations to test the robustness of our results to different samples and specifications. First, we run our main model including exporting firms. In the main analysis we excluded exporters and opted for a more homogeneous sample of firms serving domestic markets, noticing that domestic certificates are not likely to act as signalling devices for foreign customers. Moreover, considering that exporting firms are operating in larger markets in more competitive regimes, their growth performance is indeed likely to be subject to a different set of factors. Nevertheless, exporting firms can also be active on the domestic market, thus having a domestic certificate could influence the domestic share of their sales performance. Therefore, we add to the considered sample exporting firms that have at least 5 per cent of domestic sales and calculate the growth of their domestic sales. Results are presented in , columns (1) and (2). Even with this larger and more diverse sample, the link between certification and sales growth remains supported, especially for international certificates. Second, we estimate our main models splitting the sample by ownership type: household establishments, representing the largest portion in the considered sample (70%; see ), versus other ownership types. The results show that the effects of domestic certification are stronger for household enterprises. This is consistent with the notion that non-household enterprises tend to be larger and with stronger market power, facing less transaction costs in the domestic market.

Table 6. The effect of domestic certificates on sales growth: different samples

5.3.2. Propensity score matching (PSM)

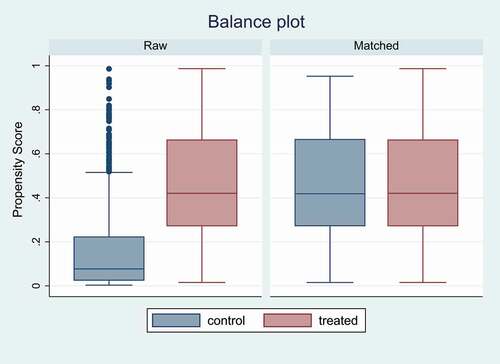

Finally, we implement a propensity score matching (PSM) non-parametric estimation. Using the same covariates of the original probit for domestic certification,Footnote8 we estimate a propensity score for having a domestic certificate (treatment), which we use to match certified and non-certified firms. To check whether the range of values of the propensity score is actually the same for treated and control firms, we plot the estimated propensity scores for the two groups before and after matching ().

Figure 1. Balance box plot: domestic certificate

compares the results of one-to-one and one-to-three nearest neighbour, and kernel-based matching. Panel A displays the results for the whole sample, where the treated group includes some firms with both domestic and international certificates. The found ATET is significant and positive in all estimations, falling within a range between 0.116 and 0.080. This effect is close to the coefficient obtained with the OLS (see , column (1)), while it is smaller than the one obtained with the simultaneous estimations (see , column (2)). To further check whether this result may be driven by international certificates, we next exclude from the sample all internationally certified firms, so that the treated group includes firms with domestic certificates only. As shown in Panel B, having only a domestic certificate still has a positive and significant ATET, whose magnitude falls within a range between 0.080 and 0.090. This is consistent with what we found in the main model ( columns (4) and (5)): domestic certificates still have an independent effect on sales growth, this becoming slightly weaker when accounting for international certificates.

Table 7. Average treatment effect on the treated (ATET)

6. Discussion

This work contributes to the debate on the performance of entrepreneurial firms in a developing and emerging context by providing original firm-level empirical evidence on the relationship between domestic certificates and sales growth using a sample of MSMEs operating in Viet Nam manufacturing sector. Domestic certificates have so far been largely disregarded by existing empirical analyses, partly due to difficulties in collecting relevant information in a developing context, partly due to being perceived as less important in influencing firm performance because they are less demanding and less costly than international standard certificates. Our results indicate instead that domestic certificates can flag desirable intangible attributes and are associated with additional growth opportunities for micro and small firms operating almost exclusively on the domestic market.

This work finds evidence of a positive correlation between domestic certification and sales growth, this result being persistent across different specifications and estimation methods, even when controlling for international certification. We argue that this growth premium derives from a competitive advantage enjoyed by firms with a domestic certificate as result of this serving as signalling devices to communicate quality and other attributes that are otherwise difficult to observe and assess, especially in markets where distrust regarding product quality and environmental conduct are widespread. Thus, domestic certificates may play a role per se, independently from eventual certification-driven improvements in organisational, operational, and environmental performance. This does not mean that these efficiency improvements cannot affect sale growth; rather, it shows that concentrating only on certification-induced operational improvements cannot fully explain the mechanisms of how certificates influence firms’ performance (Terlaak & King, Citation2006). Hence, the ‘piece of paper’ of a domestic certificate could be an effective way to increase reputation by disclosing quality and other attributes that are relevant in influencing costumers’ decisions.

Our results also provide evidence that being certified is more convenient when information asymmetry is particularly large. The result about female-run businesses is paradigmatic. When female-run businesses are perceived as less credible or reliable, female managers may find it more difficult to gain legitimacy and customers. In this case, certificates can help them better flag their quality and other valuable intangible attributes and improve their sales performance. Ultimately, this increase in reputation may contribute to women’s empowerment. Gender bias in business is generally less diffused and less serious in Viet Nam with respect to other developing economies, also thanks to the implementation of new legislation (for example, Law on Gender Equality 2010) and gender-equality policies addressing gender inequality since the mid-2000s (Wells, Citation2005). Yet, traditional patriarchal attitudes and gender stereotypes may persist also in Vietnamese society and economy, reflecting into wage-gender gaps (Bjerge, Torm, & Trifković, Citation2016), exposure to more vulnerable jobs and unpaid housework, and prejudice towards women taking up leadership positions. The presence of gender gaps is thus still an issue even in this country.

The positive effect of domestic certifications in Viet Nam can be better understood when acknowledging that environmental pollution and food safety have become major issues in current Vietnamese societal and political debate (Chu, Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2017). As living conditions improve, Vietnamese costumers are becoming increasingly sensitive and demanding in terms of quality and environmental safety, actively calling for better and safer products and productions. In this context even a domestically awarded food safety certificate or a domestically awarded environmental standard certificate (ESC) can help flag the presence of some intangible features that are important for costumers’ decisions, such as the quality of food processing and/or the implementation of environmental control treatments. This increased relevance of costumers’ demand is also consistent with our findings on the importance of institutional pressure on the likelihood of having a domestic certificate, further confirming what was already noticed by Fikru (Citation2014) and Liu et al. (Citation2010) that the influence of institutional pressure on certificate adoption tends to be more relevant in the weak regulatory and institutional environments that often characterise emerging and developing economies. As the compliance with safety and environmental standards is becoming a requirement for the suppliers of the domestic market in other developing and emerging countries (Holzapfel & Wollni, Citation2014), domestic certificates may contribute to sustain entrepreneurial firm growth beyond the specific case of Viet Nam manufacturing sector.

While the adoption of international standard certificates such as ISO 9001 or ISO 14001 is typically associated with pressure from foreign markets, obtaining a domestic certificate may present less drawbacks associated with high entry and market barrier for the smallest and resource poor firms. Even if cheaper in terms of direct costs and potentially less demanding in terms of technical requirements, domestic certificates are often designed on the basis of international ones, thus do not necessarily have to be interpreted as their ‘minimal version’ (Zoo et al., Citation2017). With much smaller numbers of SMEs able to obtain international certification, the found evidence supports the idea that domestic certificates can act as an intermediate step to signal quality and they may serve as a sort of more convenient and easier-to-access first stage in preparation to adopt an international certificate. A better understanding of the relationship between domestic and international certificates would be very relevant for Viet Nam, which more than a decade after joining the WTO is still struggling with meeting international safety and quality regulations, with the consequent frequent cases of product detention and rejection at the borders. The signing of a trade agreement with the European Union at the beginning of 2017 represented a great opportunity for the country, but the high level of contamination and poor quality still affect Vietnam’s reputation amongst its trading partners (World Bank, Citation2017).

The obtained results offer new insights for the design and implementation of entrepreneurial policies in a developing context. Promoting the diffusion of domestic certification might be a way to foster entrepreneurial growth of micro and small business venues. As emphasised by our findings on mimetic pressure and the diffusion of information and practices, the implementation of initiatives fostering the adoption of domestic certificate may be a cost-effective policy tool, especially in a context where the collection of relevant information is challenging and businesses are likely to not be well informed about certificates, nor fully aware of their potential benefits. On the other hand, it has to be reminded that successfully leveraging entrepreneurial growth with domestic certificates requires informed, aware, and demanding domestic customers, in order for certified firms to exploit growth opportunities by catering the internal market. The weaker customers’ response to domestic certificates, the weaker the impact of so designed policies.

7. Conclusions

Using simultaneous estimations to deal with endogeneity and checking the robustness of the findings with different estimation methods, the presented empirical analysis provides evidence of a positive correlation between sales growth and having a domestic certificate, the latter acting as a signalling device to overcome transaction costs and increase growth among manufacturing MSMEs in Viet Nam. The effect come in addition to an eventual internal effect of certification, inducing operational improvements. The signalling effect is found to be stronger for female run businesses and in the case of newly acquired certificates. By showing the potential of having a domestic certificate on growth, it offers more insights to assist the design and implementation of more effective entrepreneurial policies.

We are aware of the limitations of this study. The availability of unique information about domestic certificates is paired with the impossibility to perform panel analysis, which limits the range of employable estimation techniques and does not allow to fully account for selection on unobservables, and thus to fully claim for causality. In terms of firm performance, we follow the extant entrepreneurship literature and use growth of revenues from sales. This implies that we are unable to say whether the effect on sales growth is driven by an increase in the markup due to a reduction in costs or an increase in price, or it is mostly a volume effect – or both. The use of other performance indicators, such as markup or profit, could provide interesting corroborating insights in this direction.

The study of domestic certificates is still at an early stage in developing countries. Its novelty makes it difficult to compare with other works in the literature and to draw broader conclusions, or to perform a cross-country comparison of their effects with the ones of international certificates. The scarce availability of data on domestic certificates currently constrains this comparative effort, but an expansion of this type of study would contribute to a better understanding of the role of certificates at firm-level.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (110.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Pierre Mohnen, Neda Trifković, Neil Foster-McGregor, and two anonymous referees for their insightful comments and advice. We thank the participants of the 10th Micro Evidence on Innovation and Development (MEIDE) Conference and the participants of the UNU-MERIT seminars for their feedback. Financial support of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 778398 is gratefully acknowledged.

We also thank UNU-WIDER for granting access to the data. The raw data are made available by UNU-WIDER at: https://www.wider.unu.edu/database/viet-nam-sme-database. The do-files with the data preparation and empirical analysis are available from the authors upon request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Materials are available for this article which can be accessed via the online version of this journal available at https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2021.1873289.

Notes

1. The survey has been conducted in collaboration between the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM) of the Ministry of Planning and Investment of Vietnam (MPI), the Institute of Labour Science and Social Affairs (ILSSA) of the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs of Vietnam (MOLISA), the Development Economics Research Group (DERG) of the University of Copenhagen, and the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). For more information about the survey and data see CIEM, DoE, ILSSA, and UNU-WIDER (Citation2016).

2. For more information on quality certificates in Viet Nam, see the website the Directorate for Standards and Quality (www.tcvn.gov.vn). See also Section 9 of UNU-WIDER (2016) for a discussion on the topic.

3. Due to changes in activity over time or to misinformation in the sampling frame, some firms appear to be operating in agriculture or services in the 2013 and 2015 waves. Similarly, even though the survey targeted private domestic enterprises, a very small number of state-owned and foreign-owned firms appear in the surveyed sample. We exclude firms in these categories from the final sample.

4. This variable is obtained from the answer to the question ‘Is your enterprise required by customers to certify certain standards of production?’, which is asked to all surveyed firms, irrespective of them having a certificate.

5. Information on the cost of domestic quality certification is available only for firms that reported to have one. Since the direct cost of a certificate is not established by the individual firm but it is set by external administrative bodies, firms located in the same administrative area (province) and manufacturing similar products (sector 4-digit) are likely to face similar direct costs when applying for a domestic quality certificate. We therefore calculate the potential direct cost faced by all firms – certified and non-certified – as a province-sector (4-digit) average. To control for a possible correlation of this variable with other province- and sector-level characteristic, we always include specific dummies for location and sector (2-digit).

6. We implement the cmp STATA command proposed by Roodman (Citation2009).

7. Since we introduce an interaction term to test the heterogeneity of the signalling effect of Domestic certificate, the full model contains two endogenous variables: Domestic certificate and its interaction with Female. We need to identify at least two variables that fulfill the exclusion restrictions and test their validity with an IV 2SLS estimation for sales growth and relevant test statistics (results available in the Supplementary Materials to this article). All used instruments significantly predict having a domestic certificate. The null hypothesis that the model is underidentified is rejected (with Kleibergen–Paap LM statistic equal to 124.298). The values of Kleibergen–Paap Wald F statistic is 100.388, larger than the rule-of-thumb value 10, while the value of Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic equals 105.645, thus surpassing the Stock-Yogo critical values for weak instruments. With a p = 0.389, the test for over-identification (Hansen-J statistic) fails to reject the null hypothesis that the instruments are valid.

8. Except the variable Cost of domestic quality certificate (available only in 2015), we use 2013 values for all explanatory variables.

References

- Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. W. (2016). Matching on the estimated propensity score. Econometrica, 84(2), 781–807.

- Audretsch, D. B., Coad, A., & Segarra, A. (2014). Firm growth and innovation. Small Business Economics, 43(4), 743–749.

- Becker, S., & Ichino, A. (2002). Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. The STATA Journal, 2(4), 358–377.

- Bjerge, B., Torm, N., & Trifković, N. (2016). Gender matters: Private sector training in Vietnamese SMEs (WIDER Working Paper 2016/149). Helsinki, Finland: UNU-WIDER.

- Calza, E., Goedhuys, M., & Trifković, N. (2019). Drivers of productivity in Vietnamese SMEs: The role of management standards and innovation. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 28(1), 23–44.

- Chu, T. T. H. (2018). Environmental pollution in Vietnam: Challenges in management and protection. Journal of Vietnamese Environment, 9(1), 1–3.

- CIEM, DoE, ILSSA, & UNU-WIDER. (2016). Characteristics of the Vietnamese business environment. Evidence from a SME survey in 2015. Hanoi, Viet Nam: Central Institute of Economic Management (CIEM).

- Clougherty, J. A., & Grajek, M. (2014). International standards and international trade: Empirical evidence from ISO 9000 diffusion. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 36, 70–82.

- Coad, A. (2009). The growth of firms: A survey of theories and empirical evidence. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Delmas, M. A., & Montiel, I. (2008). The diffusion of voluntary international management standards: Responsible care, ISO 9000, and ISO 14001 in the chemical industry. Policy Studies Journal, 36(1), 65–93.

- Delmas, M. A., & Pekovic, S. (2013). Environmental standards and labor productivity: Understanding the mechanisms that sustain sustainability. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 230–252.

- DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The Iron Cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

- Doms, M., Dunne, T., & Roberts, M. J. (1995). The role of technology use in the survival and growth of manufacturing plants. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4), 523–542.

- Elam, A., & Terjesen, S. (2010). Gendered Institutions and cross-national patterns of business creation for men and women. The European Journal of Development Research, 22(3), 331–348.

- Ericson, R., & Pakes, A. (1995). Markov-perfect industry dynamics: A framework for empirical work. The Review of Economic Studies, 62(1), 53–82.

- Evans, D. S. (1987a). The relationship between firm growth, size, and age: Estimates for 100 manufacturing industries. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 35(4), 567–581.

- Evans, D. S. (1987b). Test of alternative series of firm growth. Journal of Political Economy, 95(4), 657–674.

- Fikru, M. G. (2014). International certification in developing countries: The role of internal and external institutional pressure. Journal of Environmental Management, 144, 286–296.

- Gallego, J. M., & Gutiérrez, L. H. (2017). Quality management system and firm performance in an emerging economy: The case of colombian manufacturing industries (IADB Working Paper Series 803). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank (IADB).

- Gebreeyesus, M. (2015). Firm adoption of international standards: Evidence from the Ethiopian Floriculture Sector. Agricultural Economics, 46(S1), 139–155.

- Goedhuys, M., & Mohnen, P. (2017). Management standard certification and firm productivity: Micro-evidence from Africa. Journal of African Development, 19(1), 61–83.

- Goedhuys, M., & Sleuwaegen, L. (2010). High-growth entrepreneurial firms in Africa: A quantile regression approach. Small Business Economics, 34(1), 31–51.

- Goedhuys, M., & Sleuwaegen, L. (2013). The impact of international standards certification on the performance of firms in less developed countries. World Development, 47, 87–101.

- Hansen, H., & Trifković, N. (2014). Food standards are good – For middle-class farmers. World Development, 56, 226–242.

- Henson, S., & Jaffee, S. (2006). Food safety standards and trade: Enhancing competitiveness and avoiding exclusion of developing countries. The European Journal of Development Research, 18(4), 593–621.

- Henson, S., Masakure, O., & Cranfield, J. (2011). Do fresh produce exporters in Sub-Saharan Africa benefit from GlobalGAP certification? World Development, 39(3), 375–386.

- Ho, H.-A. (2016). Business compliance with environmental regulations: Evidence from Vietnam (EEPSEA Research Report, 2106-SRG4). Laguna, Philippines: Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia.

- Holleran, E., Bredahl, M. E., & Zaibet, L. (1999). Private incentives for adopting food safety and quality assurance. Food Policy, 24(6), 669–683.

- Holzapfel, S., & Wollni, M. (2014). Is GlobalGap certification of small-scale farmers sustainable? Evidence from Thailand. The Journal of Development Studies, 50(5), 731–747.

- Hudson, J., & Jones, P. (2003). International trade in ‘quality goods’: Signaling problems for developing countries. Journal of International Development, 15(8), 999–1013.

- Hudson, J., & Orviska, M. (2013). Firms’ adoption of international standards: One size fits all? Journal of Policy Modeling, 35(2), 289–306.

- Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50(3), 649–670.

- Kantor, P. (2005). Determinants of women’s microenterprise success in Ahmedabad, India: Empowerment and economics. Feminist Economics, 11(3), 63–83.

- King, A. A., Lenox, M. J., & Terlaak, A. (2005). The strategic use of decentralized institutions: Exploring certification with the ISO 14001 management standard. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1091–1106.

- Liu, X., Liu, B., Shishime, T., Yu, Q., Bi, J., & Fujitsuka, T. (2010). An empirical study on the driving mechanism of proactive corporate environmental management in China. Journal of Environmental Management, 91(8), 1707–1717.

- Masakure, O., Cranfield, J., & Henson, S. (2011). Factors affecting the incidence and intensity of standards certification evidence from exporting firms in Pakistan. Applied Economics, 43(8), 901–915.

- Masakure, O., Henson, S., & Cranfield, J. (2009). Standards and export performance in developing countries: Evidence from Pakistan. The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 18(3), 395–419.

- Maskus, K. E., Otsuki, T., & Wilson, J. S. (2005). The cost of compliance with product standards for firms in developing countries: An econometric study (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3590). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Maskus, K. E., Otsuki, T., & Wilson, J. S. (2013). Do foreign product standards matter? Impacts on costs for developing country exporters. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting and Economics, 20(1), 37–57.

- Melesse, M. B., Dabissa, A., & Bulte, E. (2018). Joint land certification programmes and women’s empowerment: Evidence from ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(10), 1756–1774.

- Nguyen, Q. A., & Hens, L. (2015). Environmental performance of the cement industry in Vietnam: The influence of ISO 14001 certification. Journal of Cleaner Production, 96, 362–378.

- Pakes, A., & Ericson, R. (1998). Empirical implications of alternative models of firm dynamics. Journal of Economic Theory, 79(1), 1–45.

- Park, Y., Shin, Y., & Kim, T. (2010). Firm size, age, industrial networking, and growth: A case of the Korean Manufacturing Industry. Small Business Economics, 35, 153–168.

- Pham, T., & Talavera, O. (2018). Discrimination, social capital, and financial constraints: The case of Viet Nam. World Development, 102, 228–242.

- Phan, U. H. P., Nguyen, P. V., Mai, K. T., & Le, T. P. (2015). Key determinants of SMEs in Vietnam. Combining quantitative and qualitative studies. Review of European Studies, 11, 359–375.

- Potoski, M., & Prakash, A. (2005). Green clubs and voluntary governance: ISO 14001 and firms’ regulatory compliance. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 235–248.

- Potoski, M., & Prakash, A. (2009). Information asymmetries as trade barriers: ISO 9000 increases international commerce. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 28(2), 221–238.

- Roberts, M. J., & Tybout, J. R. (1996). Industrial evolution in developing countries: A preview. In M. J. Roberts & J. R. Tybout (Eds.), Industrial evolution in developing countries: Micro patterns of turnover, productivity, and market structure (pp. 1–14). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Roodman, D. (2009). Estimating fully observed recursive mixed-process models with cmp (Working Paper 168). Centre for Global Development.

- Scott, W. (1995). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests and identities. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications.

- Sharma, S., & Tarp, F. (2018). Does managerial personality matter? Evidence from firms in Vietnam. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 150, 432–445.

- Sleuwaegen, L., & Goedhuys, M. (2002). Growth of firms in developing countries, evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Development Economics, 68(1), 117–135.

- Sutton, J. (1997). Gibrat’s legacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 40–59.

- Terlaak, A., & King, A. A. (2006). The effect of certification with the ISO 9000 quality management standard: A signaling approach. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 60(4), 579–602.

- Trifković, N. (2016). Private standards and labour productivity in the food sector in Viet Nam (WIDER Working Paper 2016/163). Helsinki, Finland: UNU-WIDER.

- Trifković, N. (2017). Spillover effects of international standards: Working conditions in the Vietnamese SMEs. World Development, 97, 79–101.

- Trifković, N. (2018). Certification and business risk (WIDER Working Paper 2018/80). Helsinki, Finland: UNU-WIDER.

- Tybout, J. R. (2000). Manufacturing firms in developing countries: How well do they do, and why? Journal of Economic Literature, 38(1), 11–44.

- UN Women, & OHCHR. (2013). Realizing women’s rights to land and other productive resources (Tech. Rep.). New York and Geneva: UN Women. Retrieved from http://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2013/11/realizing-womens-right-to-land

- Wells, M. (2005). Viet Nam: Gender situation analysis ( Strategy and Program Assessment). Asian Development Bank (ADB). Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32246/cga-viet-nam.pdf

- World Bank. (2017). Vietnam food safety risks management: Challenges and opportunities - Key findings (English) (Tech. Rep.). Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/235741490717293094/Vietnam-food-safety-risks-management-challenges-and-opportunities

- Yasuda, T. (2005). Firm growth, size, age and behavior in Japanese manufacturing. Small Business Economics, 24, 1–15.

- Zoo, H., de Vries, H. J., & Lee, H. (2017). Interplay of innovation and standardization: Exploring the relevance in developing countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 118, 334–348.